A New Insurgency: The Port Huron Statement and Its Times

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Prologue

Before Port Huron

In all the writings about the Port Huron Statement, three 1962 documents have never been published until now. Historians and activists should find them interesting as “windows” into the internal and improvised thinking that finally resulted in the twenty-five-thousand-word finished product in June 1962. The memos ramble, wander, speculate, embarrass, and frustrate the reader. But they reveal an honest searching—not packaged talking points—meant to stimulate the coming days of discussion at Port Huron that resulted in the Statement. Convention Documents #1 and #2, both dated March 19, 1962, along with an undated third memo, were sent to Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) delegates on April 25.

The mailing looked duller than any publication I remember from the sixties. The twenty-page, single-spaced, mimeographed “Convention Bulletin/number one” of SDS was mailed from a cluttered New York office on April 25, 1962, announcing that a national convention would take place in mid-June, the location still to be announced, but “somewhere toward the East,” perhaps a mid-Atlantic state, or maybe Michigan.

It was an inauspicious, unattractive invitation to participate in the writing of the Port Huron Statement two months later. No graphics, no charts, no color, only typing in black and white.

“It’s necessary to establish some order,” according to the bulletin. Our one-dollar dues weren’t being paid. Membership wasn’t clearly defined, and voting at the upcoming convention, when the place was located, would be limited strictly to members. Six weeks later, about sixty-three certified members would participate at Port Huron.

The component parts of the future SDS were being assembled. Membership would escalate from sixty-three to more than one hundred thousand within five years. Two weeks before the first “Convention Bulletin” was issued, SDS was a cosponsor of the first national conference of independent student political parties at Oberlin College, in Ohio, coordinated by Oberlin student Rennie Davis, who would go on to play a leading role in the Vietnam antiwar movement five years later. According to the “Convention Bulletin,” the SDS line was that “the university as an agent of social change, rather than the transmitter of culture-as-we-know-it, should be our goal,” to be achieved by students working for reform. In those days it was heretical to claim that students and young intellectuals—as opposed to factory workers, peasants, or “adult” intellectuals—could be an agency of radical change in our own right. This was the idealistic seed of what became known as the “new working class” in the emerging “knowledge economy,” an attempt to pour new wine into old bottles.

How did the Oberlin conference come to pass? When I became editor of the Michigan Daily in spring 1960, I hitchhiked that summer to California, writing short stories “on the road,” following my curiosity toward two beacons of change. First, I planned to hang out in Berkeley for a few weeks, trying to understand and write for the Daily about the spirit of student activism in the air. Then I would visit the Democratic convention in Los Angeles, where I unexpectedly met Martin Luther King Jr. on a picket line while writing about the New Frontier for the Daily.

In that summer of 1960, my life floated between a Berkeley crash pad and the Los Angeles convention booth of the Detroit News, whose editor quartered me as a Michigan favor. In Berkeley, a little activist circle gladly put me up in an apartment where intense political discussions went on 24–7. An idealistic student editor from Ann Arbor was a find, a potential recruit to their grand revolutionary design. These were the founders of SLATE, the earliest student party fighting the university over the right of students to take stands on “off-campus” issues. Already in 1960, SLATE had made an issue of free-speech rights at the campus’s traditional rallying point, Sather Gate, several years before the massive Free Speech Movement (FSM) electrified Berkeley and the world. What was at stake for FSM was the right to leaflet undergraduates to join the burgeoning civil disobedience campaign against Jim Crow. My new friends pushed me to advocate and form a similar campus party when I returned to Ann Arbor. This I did by making a public speech that fall calling on students to speak out, which led to VOICE, the first chapter of SDS. Meanwhile, my lengthy Daily dispatches from summer 1960, and afterward, about the student movement caused extreme anxiety among University of Michigan administrators, who worried that a picket line would escalate into full-blown revolution. At the time I was just learning the difference between a picket line and a picket fence, but I could see something arising from beneath the surface of apathy, which they either wanted to deny or suffocate.

In October 1960, Senator John Kennedy made a historic campaign stop in Ann Arbor where I took notes and accompanied him up a Michigan Union elevator. Just before his speech, a small activist group succeeded in handing him a letter with my signature at the top, calling on Kennedy to push for disarmament; one of our lesser utopian demands was to create a peaceful alternative to military conscription. Kennedy read the letter on the spot, told us he would refer to it in his impromptu remarks, stepped out into the October rain, and endorsed the Peace Corps.

These two experiences, at Berkeley’s Sather Gate and on the steps of the Michigan Union, are marked by historic plaques today. I had the prophetic sense that there could be a rich intertwining of the new student movement and the New Frontier. SDS and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) were perfectly positioned to exploit the historic moment. We needed the president to reverse the nuclear arms race and protect civil rights workers in the South. He needed a new generation of student activism.

After Kennedy barely won the election, 1961 was filled with ups and downs, including the shocking Bay of Pigs invasion. I took more trips to the southern frontlines, and in May a university scandal erupted that brought home the crises of race and student rights. The Daily exposed how the dean of women spied on white co-eds seen in the company of any black men. Before that scandal, I never heard of “investigative journalism” except in occasional references to “muckrakers” long before our time. The university was driven by in loco parentis doctrine to treat undergraduates as some sort of preadults, which clashed with our activist impulses. The mass university felt like a paternalistic plantation. We didn’t face the violence endured by southern blacks, but we had no voice, no vote; we could be expelled from school or fired without cause and, in the case of young men, drafted into “twilight” wars we knew or cared little about.

Experiences such as these, on campus and in the South, shaped my evolving thought process. Witnessing black sharecroppers claiming their rights taught me that democracy still required battle and sacrifice. It would not be given but only wrested from the powers that be. It required a faith in the potential of people whose very color and dispossession made them “unqualified” to participate in decisions affecting their lives. I discovered that the limits of my elite education in Ann Arbor could be overcome only by direct experience among people who couldn’t themselves be admitted. The eye-opening experience of participatory democracy made possible the thought.

Nineteen sixty-one was the pivotal year when most SDS leaders graduated from college and were “looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.”[1] That December in Ann Arbor, a small planning meeting assigned me to draft a vision statement for the first SDS convention the next summer. Actually, we didn’t use today’s organizational planning term, “vision statement”; the SDS preconvention planners described it in more left-wing language as a “manifesto,” and, in the end, it became “the Statement,” “a living document open to change with our times and experiences.”[2]

I left the South to closet myself in a dingy New York railroad apartment buried amid hundreds of books and articles, searching for the concepts and language that might give voice to a student movement that did not even exist in the minds of any mainstream Americans or journalists. Unfortunately, John Dewey, the theorist of learning by doing, had passed a decade before. In Ann Arbor we had some supportive faculty friends like Kenneth and Elise Boulding, Ted Newcomb, and Arnold Kaufman, who first used the phrase “participatory democracy” in 1960. Among the media there was the New York Times correspondent Claude Sitton, who had taken notice of SNCC on the southern frontlines. The iconic Albert Camus died in 1960, Frantz Fanon in 1961, and C. Wright Mills just one month before the “Convention Bulletin” was mailed out. Some like myself had read the Beats and had grown up absurd, in the phrase of Paul Goodman, but didn’t believe madness was the only proper response. I craved for a political “Howl.” I empathized with James Joyce’s yearning to express “the uncreated conscience” of our generation.

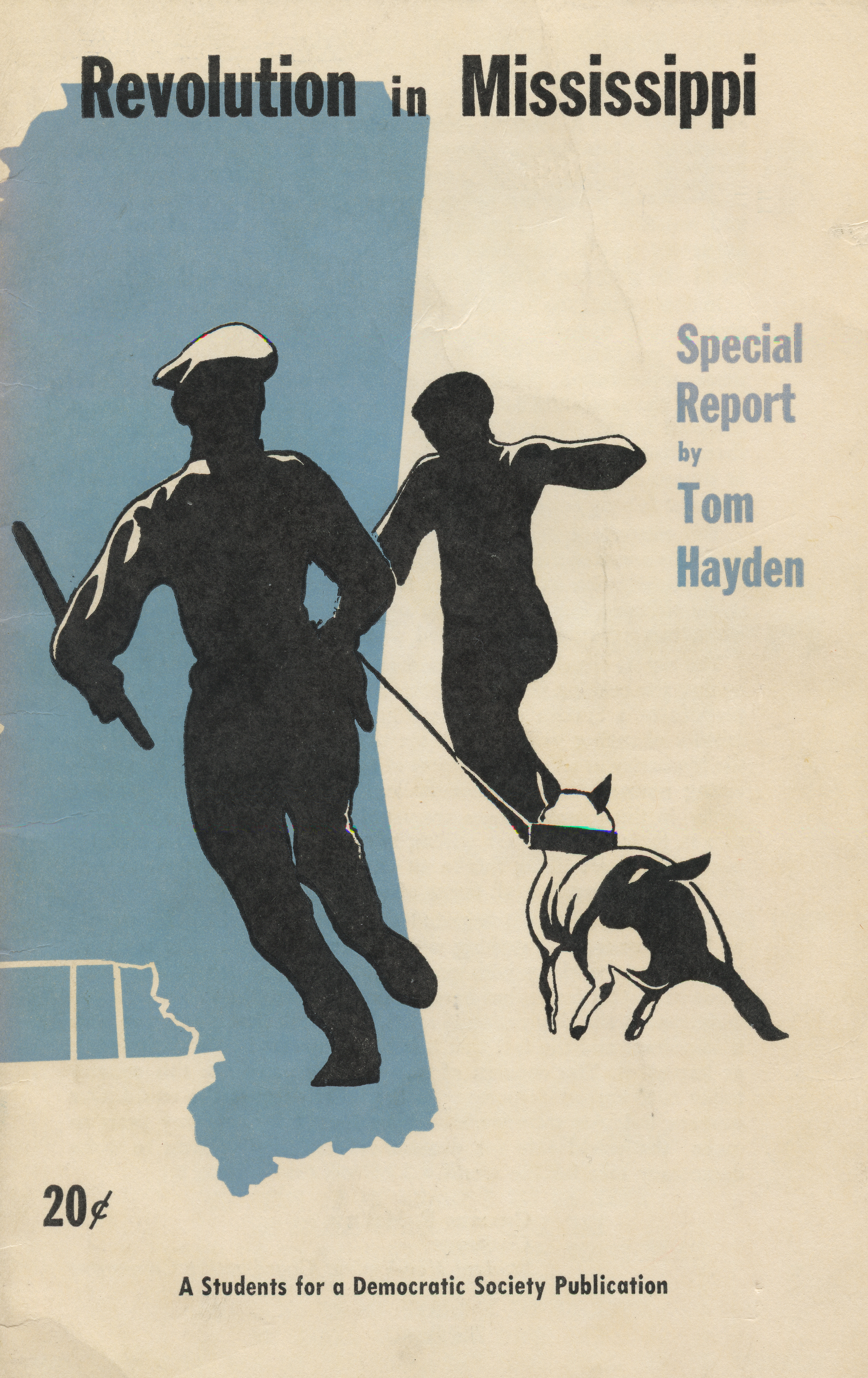

If creating campus chapters were the first blocks in building SDS, anchoring ourselves in an alliance with SNCC was equally important as far as I was concerned. SNCC leaders recognized me as a useful writer and speaker to carry their message north. Charles McDew and Julian Bond believed that if a white Tom Hayden was beaten up in the Black Belt, that would help end the blackout of mainstream news coverage, draw the Justice Department’s attention, and perhaps deter violent attacks on black people trying to vote. They were proven right when an Associated Press photo of me being kicked and beaten in McComb, Mississippi, in October 1961, along with future SDS president Paul Potter, went global. I did speak to Burke Marshall, Robert Kennedy’s civil rights deputy in the Justice Department, and my January 1962 report, Revolution in Mississippi, was published by SDS and widely circulated on campuses everywhere.

SNCC decided then they would send delegates to attend the SDS convention, wherever it would be. That meant we had secured an interracial alliance with the most important force in the student and civil rights movements. SNCC sought to use SDS for outreach and recruitment, but as young intellectuals they too were drawn to participatory democracy. For them, gaining democracy was a life-or-death matter, and “participation” meant putting one’s body on the line as a necessary step toward voting rights. Many had studied Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience,” especially the passage about voting with “one’s whole life,” not only with “a mere strip of paper.”

On May 4–6, 1962, one month before Port Huron, we organized a workshop of SDS and SNCC organizers on “race and politics in the South,” in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. There we laid plans for pushing the racist Dixiecrat bloc out of their dominance in national politics, a power based entirely on suppressing blacks’ right to vote. The meeting solidified an understanding that SNCC workers were the shock troops, or vanguard, in a struggle toward a wider political goal: by enfranchising black people in the South, the racist Dixiecrat order could be overthrown. But a frontline struggle wasn’t enough. A mobilization of political conscience was needed among constituencies across the country, especially among northern Democrats and labor who would gain from expelling the Dixiecrats. Students would be the catalysts, but the effort required a coalition of labor, clergy, and rank-and-file Democrats. That was the plan as we left Chapel Hill. The SDS manifesto would focus on that political goal.

This strategy, however, contained an underlying tension within SDS—between those from liberal-left backgrounds who saw realignment as a political end in itself and those who sought more radical goals that could not be achieved through a realignment of the two political parties. Beyond a more representative democracy, for example, lay the quest for a participatory democracy sought in the workplace and family life. Realignment alone could not express the emerging cultural revolution among young poets, musicians, and Beats. These differences foreshadowed, in a way, the division several years later between the more ideological New Left, on the one hand, and a “movement politics” based on changing morality, culture, and spirituality, on the other. Both would be needed for a time. The Statement would have to blend the differences.

We all came to Port Huron as seekers. We were young, the age of soldiers. Many of our friends had seen battle and shed blood in the South. Our lives were altered, our career paths deflected. Beyond voting rights, a war on poverty, a reversal of the Cold War—all wildly ambitious in scope—there were even more fundamental questions to be settled at Port Huron. To what values, what hopes, were we committing the rest of our lives? We already had formed parts of the whole—chapters, legal defense, newsletters, political campaigns, and so on—but what was the larger cause, the connecting vision that let us call ourselves “brothers and sisters” and speak of a “blessed community”? These were existential questions.

The three preparatory memos published in this book give an insight into these deeper concerns and how some of us prepared for them. They are not notes toward a political platform so much as a philosophical and moral one. They are worth reading today if only to sense our struggle to become articulate. Since they are very wordy, here is a brief guide to their content.

“Convention Document #1” proposes that we attempt to build “a house of theory,” a phrase borrowed by the British writer Iris Murdoch. Beginning with a complaint that we were living in “a barren period in the development of human values,” the memo paraphrases Murdoch as commenting that “our liberal and socialist ancestors were plagued by vision without program while our generation is plagued by program without vision.” Our generation lacked “authentic prophets.” We sought an intellectual and political practice that would not result in compromise and selling out, and a “house of theory” might meet that need. Given our experience, we went beyond the notion of an overly intellectual “house” by insisting that its foundation should be built “right out in public, in the middle of the neighborhood.”

The very lengthy “Convention Document #2,” called “Problems of Democracy,” is like a university thesis going through the many intellectual objections to participatory democracy (that it rests on a utopian view of human nature, which is selfish; that it requires too much complex information for masses of people to absorb; that it leads to “the sovereignty of the unqualified” or to mass totalitarian movements; that students cannot be equals with the experienced faculties instructing us, etc.). Twenty-five books and papers are cited in the bibliography, with Erich Fromm the most extensively quoted. The purpose of this document was to fortify us against the pervasive belief, internalized among us, that the general public wasn’t qualified to participate in the decisions affecting their lives. In contrast to this elite view, the paper quotes Fromm approvingly where he wrote that democracy was only possible in an economic system that works for the vast majority of the population, including “democracy in the work situation.” In its summary, the document speaks of participatory democracy as liberating the potential of the individual and the overall quality of life (a theme emphasized by Arnold Kaufman).

The third set of notes, titled “RE: Manifesto,” is written “in the best tradition of groping” but definitely advances toward the final arguments of the Port Huron Statement. The overarching issues are stated briefly and with frank confusion about where SDS should stand. The Cold War/nuclear arms race is identified first, with a question about whether advocating unilateral disarmament would “cut one off totally.” Instead, “I think we might talk about the Bomb as something that’s been with us nearly all our life . . . and the brutalizing effect it has had on our sense of values.” The other big issue identified was “the anti-colonial revolution,” including not only our civil rights movement but the question of the Cuban Revolution, where the liberals are slapped for excluding Cuba from the Organization of American States (OAS).

These big topics aside, the rest of the long manifesto is about a moral awakening to the democratic value of direct action and participation. “I think we want to say something about ourselves before we dash off our political perspective,” the document begins, a foreshadowing of the Port Huron conference decision to begin the Statement with the “Values” section coming first. “Normative theories of creativity ought not to go unattached to the advocacy of ‘realignment,’” it goes on, in response to the SDS faction bent on political realignment as their program. Later, the memo extols the spontaneous activism of the emerging New Left and cautions against imposing a preexisting program. The SNCC activists should be respected for the courage to stand up (“whose courage is their own courage”) and for wishing to be “creators instead of simply creatures.” Let this new spirit “remain ambiguous for a while; don’t kill it by immediately imposing formulas for ‘realignment.’ We have to grow and expand, and let moral values get a bit realigned.”

What are we to make of this? The Port Huron Statement was an intentional blend of contending visions at the time, held together by a binding sense that we were giving birth to something new and unique. Given the fact that a whole section of the Statement on spirituality was left on the floor when the sleepless delegates staggered away, it is fair to say that the original draft was a blend of the spiritual and political with the overriding goal of declaring ourselves as the first major American student movement. For a creative time, the blending worked well—the drive toward the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which fulfilled the quest for political realignment; President Kennedy’s 1963 nuclear arms treaty and speech against the Cold War; and the 1964 Berkeley Free Speech Movement, which fully expressed and built on the ideals of the Port Huron Statement.

After those victories, the process withered. The goal of “expelling the Dixiecrats” mentioned in the 1962 documents faltered when the Democrats in 1964 rejected the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a perfect model of participatory democracy. The Vietnam escalation in 1965, which we could not anticipate in 1962, turned our early hopes into ashes. The murders of King and the Kennedy brothers finished what might have been.

Among the original SDS factions, the more spiritually driven ones evolved toward the counterculture, liberation theology, or environmental movements. The politicos among us saw their realignment come to pass in the Carter and Clinton-Gore eras, including Jesse Jackson’s campaigns. Their Democratic Party splintered over Iraq and hastened corporate globalization. We named the One Percent in the Port Huron Statement but never stopped them.

Theorists from Kenneth Keniston to Richard Flacks have struggled for years to understand why, in that particular time, so many young Americans took up the paths that led to the sixties revolution. I myself have never been certain. One common trait was that many of us tended to be young leaders—student body presidents, student editors—who felt deeply thwarted and so rechanneled their energy toward rebellion. For young blacks or Latinos, the obstacles were clear. Their parents were forced to settle for lives of blocked opportunity. The young leadership of SNCC refused to accept the sentence of second-class citizenship imposed on their elders. All young women began to feel the same thwarting of their futures (we were awakening with Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, while The Feminine Mystique came one year after Port Huron). Some of our radical “best and brightest”—Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, James Baldwin, Ken Kesey—were forsaking mainstream careers in favor of a wild side. One parallel with many other social revolutions might be that an emerging leadership generation was frustrated at the prospect of whole lifetimes of disenfranchisement and blockage. Making it outrageous was the shared perception that the “adults”—those in the ruling establishment—were self-satisfied idiots. C. Wright Mills called the architects of nuclear war “crackpot realists.” The skulls of racist governors and sheriffs were bloated with preposterous nonsense. The intelligence of our professors was too often wasted on explaining the virtues of gradualism. When President Eisenhower warned in 1961 of the military-industrial complex, he was far to the left of our intellectuals.

These tensions were sharpened to a breaking point, I believe, by forces outside the common explanations of a “generation gap” as the psycho-social cause of the sixties “unrest.” Externally, the Cold War and the rise of a Non-Aligned Movement, including the Cuban Revolution, propelled the sense that another world was possible, to borrow a phrase from the 1990s antiglobalization movement. We didn’t notice it at the time, but the rising movements of black sharecroppers, Mexican farmworkers, and other displaced immigrants (Filipinos, Puerto Ricans, etc.), along with their nationalist intellectual allies, were all signs of the Third World Within, what Juan Gonzales describes as “the harvest of empire.”[3]

There was a similar generation more than a century before, the Transcendentalists, who called their time “the Newness.” Our SDS forerunners, such as Thoreau, rejected the elitism of higher education, adopted a voluntary simplicity, responded to the challenges of Frederick Douglass and John Brown, and opposed the wars against native people and the imperial war against Mexico. They too searched for a whole that was greater than the sum of its parts, a whole that was transcendent.

So did we. In our time, let no one forget, a mass movement of American students never had occurred, much less a student-led movement in American society. In those early times, both left and right defined students as a privileged handful, not the creative base for radical change. The reason some called us the New Left was that the left itself was dead effectively, done in by FBI and McCarthy’s repression, absorption into the mainstream New Deal, or sectarian self-destruction. In short, we were given no reason to believe that students as students could build a movement, and the left’s historical models were yellow blinkers warning not to go there.

On some level, history was working through us in those days leading to Port Huron. Others—the SNCC people and the numerous spiritual seekers who were at Port Huron—would more likely say that the Spirit did it, or that it was “a holy time.”[4] As a main channeler of this “history” or “spirit,” all I can add in retrospect is that it felt like the Port Huron Statement wrote us, not the other way around.