Staging Memories: Hou Hsiao-hsien’s A City of Sadness

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

2 / A Style of Unreasonable Choices

While the world of art cinema is filled with stylists, there are only a handful of filmmakers who have developed a personal approach so idiosyncratic that it is recognizable at a glance. Hou is one of those filmmakers. And City of Sadness is the film that crystallized his approach to cinematic narration. It provided a foundation from which he continues to elaborate in his subsequent films.

One of the reasons Hou Hsiao-hsien has come to the attention of critics is this cinematic style which, in its systematic rigor, has few precedents in the history of cinema. At this book’s initial writing, shortly after the release of City of Sadness, no one had brought his approach under close analysis. While it is reckless to make such assertions, we will argue that Hou’s style may be considered unique in the history of cinema. In this section we hope to describe this approach with great specificity, for it is difficult to understand the power of his films without first grasping the nature of his cinema and its relationship to thematic concerns.

Hou put this approach to cinematic narration in place early in his career, and he changes in significant ways after 1995 (see James Udden, “This Time He Moves!”). However, Hou’s cinema reaches a particular level of refinement in City of Sadness, particularly for the way cinematic style becomes inseparable from his representation of history.

Hou’s style displays characteristics we may describe as self-restricting. This general orientation toward restraint and stylization is reminiscent of Ozu Yasujiro, so much so that one is tempted to borrow David Bordwell’s characterization of Ozu’s work as an “unreasonable style,” a comparison we deal with below. In Hou’s case, the following self-restrictions have been imposed to some degree on all his films:

- The use of relatively static, extremely long takes

- Measured, rhythmic use of ellipsis

- Minimal use of tracks, pans, intrashot reframing

- Temporally unmarked transitional spaces

- Tendency toward tableaux-like long shots/few closeups

- The geometricization of space

- Delimitation of the frame

- Locking the camera/spectator onto a single axis

- Rare, strategic use of the shot–reverse shot figure

- Gradual revelation and construction of spatial relationships

- Repetition

This sounds overly programmatic (a danger in any taxonomy). However, it should be emphasized that these characteristics are entirely interrelated, as the following elaboration will show. Moreover, Hou orchestrates these qualities in such a rigorous way that they lend themselves to an equally rigorous analysis. These are legible characteristics and not dogmatic rules. At the same time, we hope to show that the rare occurrences of the staples of classical filmmaking (such as the shot-reverse shot) are crucially connected to larger issues of style, theme, and cultural codes.

The Long Take (and Neorealism)

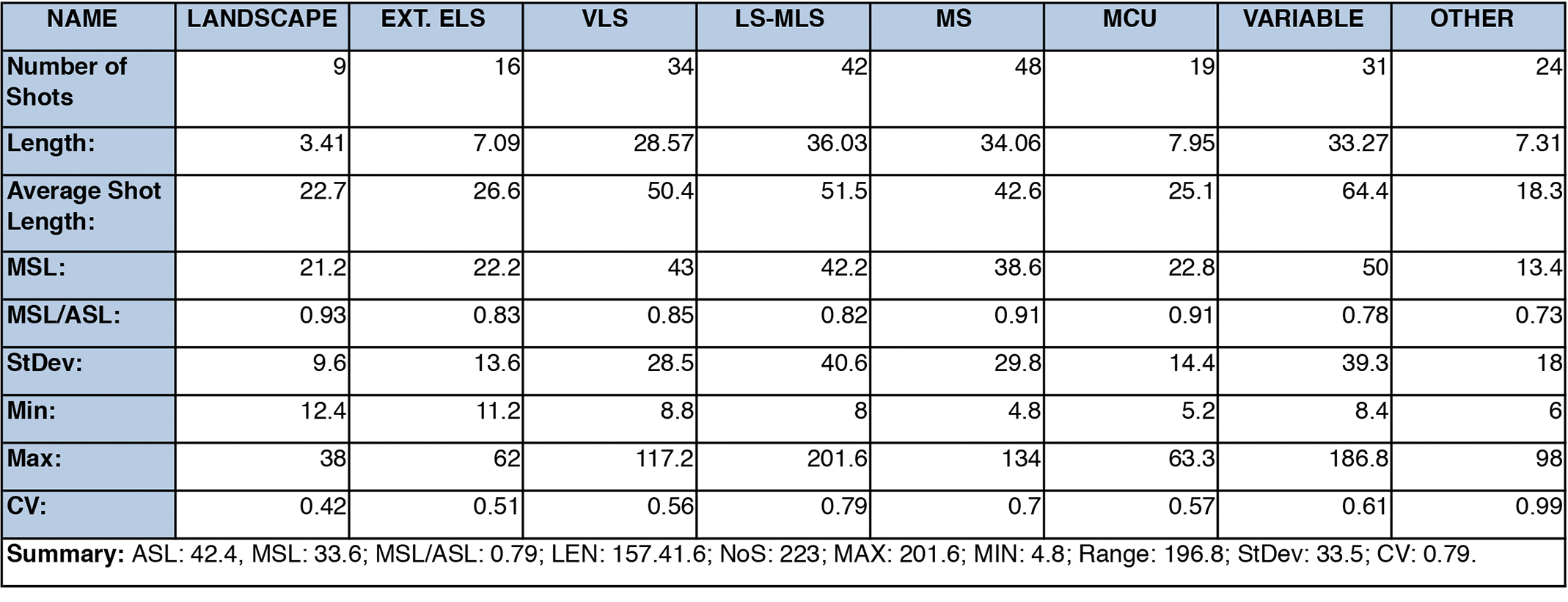

The only characteristic of Hou’s style that critics consistently single out is the long take. City of Sadness consists of 222 shots (including intertitles). With a running time of 158 minutes, that puts the average shot length at around forty-three seconds, with individual shots reaching over three minutes long. Table 1 parses the average shot lengths in the film.

Note: Drawing on a Cinemetrics analysis of the film conducted by edo (the author’s log-in name), this table describes the average shot length (ASL) in City of Sadness, arranged by shot size. The film has an ASL of 42.4 seconds, with lengths between 4.8 and 201.6 seconds for its 223 shots. Most of Hou’s shorter shots are extreme long shots or medium close-ups. By way of contrast, the Cinemetrics analysis of The Bourne Ultimatum (2007), with a running time nearly an hour shorter, showed it clocking in at an ASL of 2.1 seconds over 2,871 shots.

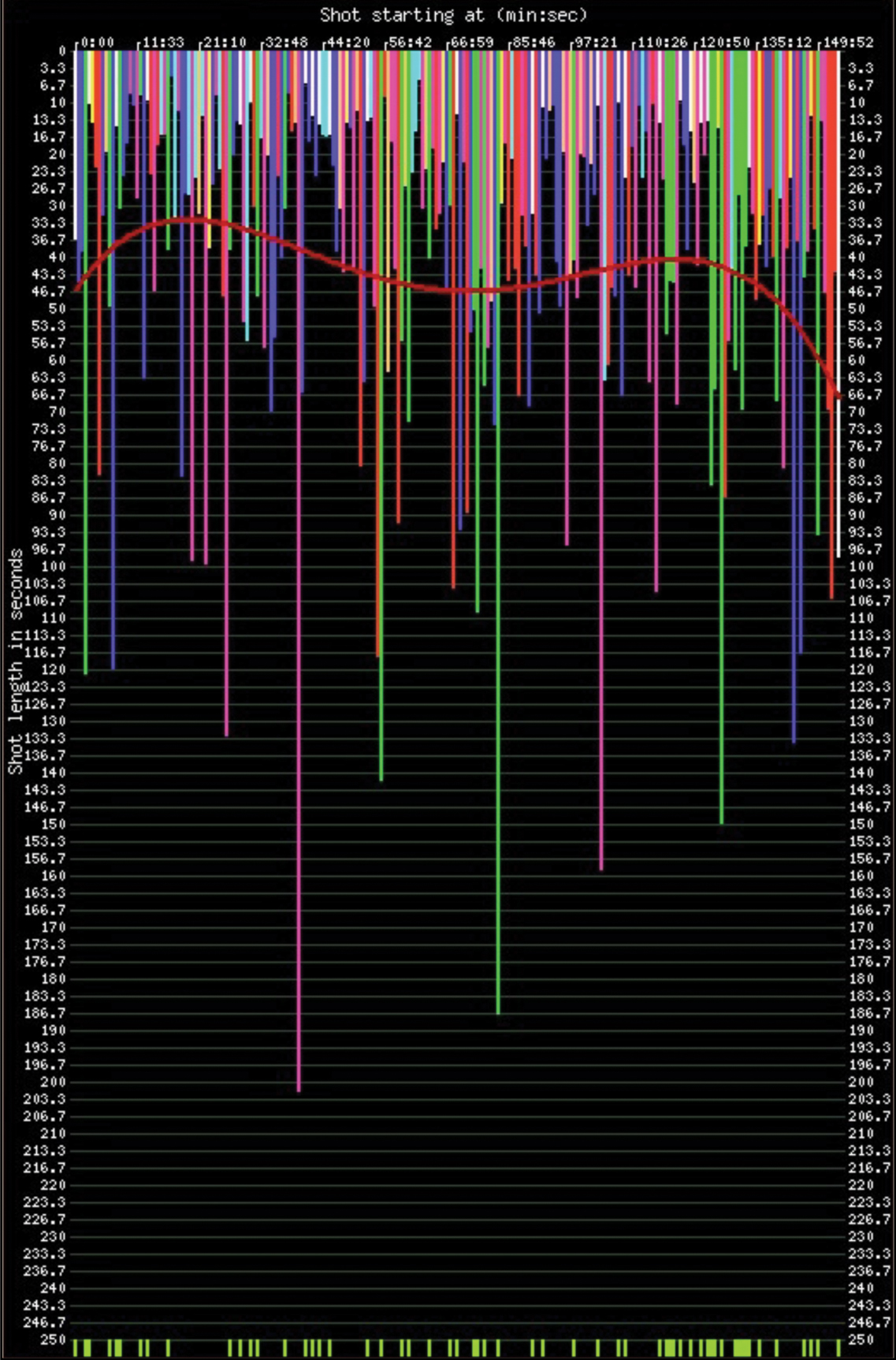

Note: This graph from Cinemetrics (created by edo) charts the length of every shot in City of Sadness, with the curved red line representing trends in shot length over the course of the film. The horizontal x-axis tracks the time code for the film, starting from left to right. The vertical y-axis corresponds to shot length. The colors are coded by scale (landscape to medium close-up). Thus, the longest shot in the film is a LS-MLS (long shot–medium long shot) occurring at 38:38, and it is 201.6 seconds long. The graph can be manipulated in a wide variety of ways by clicking through to the Cinemetrics website (http://www.cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3282).

When the long take is invoked to describe a given film, closer analysis will often show that it is used only sporadically. For example, according to Barry Salt’s calculations in “Statistical Style Analysis of Motion Pictures,” the average shot length in Renoir’s Le Crime de M. Lange is twenty-one seconds, for Citizen Kane, twelve seconds (697). In Hou’s case, the long take is surprisingly consistent from the first shot to the last. Furthermore, all of his films are similarly consistent; for example, the average shot length of Dust in the Wind is thirty-four seconds. Hou said, “I renounced fragmentary editing in favor of a sweeping style of montage, cutting not for the flow of the rhythm, but to capture the atmosphere and ‘feel’ of the shot and smooth transitions between the shots” (Jay Scott, “A Cause for Rejoicing in a City of Sadness”). This is not to say that there is no sense of rhythm; indeed, the distinction in Hou’s use of the long take is the expansive sense of a steady progression of shots at the slowest of beats, articulated by a profound application of ellipsis that is described below.

While this proclivity toward the long take nearly always invokes comparisons to Italian neorealism, there are significant differences that set Hou’s approach apart. In general, this comparison has surfaced more in regards to New Cinema (especially for its deployment of nonactors), as neorealism remains the standard against which any self-proclaimed realism is measured. We suggest that Hou’s narrations and most of the early New Cinema, films such as Kuei-mei, a Woman (Wo zheyang guo le yisheng 我這樣過了一生, 1985), Ah Fei (You ma cai zi 油麻菜籽, aka Rapeseed Girl 1984), and That Day, on the Beach (1983), are essentially based on melodrama. However, Taiwanese film tends to be more subdued than neorealism, which has moments of hysteria; it is tempting to call them “melodramas without excess.” In Hou’s case, however, we will see how truly excessive his own style is. In terms of the long take, Hou uses it in a more constant, rigorous manner than any of the international directors it is generally identified with, especially the neorealists.

Furthermore, while neorealism was about “Italy Now,” much of the New Cinema—particularly Hou’s work—has been a search for identity through reminiscences of “Taiwan Then.” In Asian film, this brand of soul-searching often leads to the countryside to find a more “authentic” or “pure” remnant of one’s culture in the face of encroaching industrialization and the explosion of consumer culture in the city. Taiwan is a small island, though, and modern transportation and media have shrunk the distance between country and city, erasing the differences between the two. This positions identity crises in the past as a site for self-examination, often using regional literature (or those writers’ scripts) as a vehicle of exploration. City of Sadness works in this mode, setting the plot at the repressed site where “Taiwanese” identity (as opposed to “Chinese”) was negotiated, formed in opposition to the arrogated centrality of the KMT. Before this moment in history, the Taiwanese relationship to the mainland was more or less unproblematic. From the 1950s to the present, the turbulent, originary period of 1945 to 1949 remained banished from the public discourse until Hou made City of Sadness. Thus neorealism is not an operative model here; its unique reputation in the history of cinema is simply hard to ignore.

Axial Alignment of the Camera/Spectator

This is the linchpin of Hou’s stylistic system. Early in the film, the director introduces various settings with specific camera angles. These angles form an axis to which the camera will return throughout the film. Depending on the axis, the camera will either be irrevocably locked into that view or it will pan from one axis to another. More simply put, whenever Hou returns to a location he uses the identical angle, the same view. He does not use the same shot, however, because the camera is positioned at various points along that axis.

An excellent example is the ambush along a country road (see fig. 3). The principle at work is obvious because the scene is split into two long takes; the only camera movement involves slight reframings. The first shot shows the second brother waiting near the camera, leisurely smoking a cigarette. This defines the axis, which runs down the road to a few houses where some carriages arrive. The brother tosses his cigarette and walks slowly toward the carriages. As he leaves the camera, the Japanese sword in one hand suddenly becomes visible and the scene is transformed with a foreboding of menacing violence. When he breaks into a run and begins fighting, the second shot jumps backward and above the first camera position, yet essentially maintains the same camera axis.

Any citizen of the cinema world knows that a standard approach to this kind of fight scene would enhance the violence through as many shots—taken from as many angles—as possible. Indeed, Hong Kong cinema takes this principle to its natural end. This scene obeys a different set of rules. At other settings in City of Sadness, this principle is always at work, though in much more subtle ways because of Hou’s use of sequence shots. A setting becomes intimately familiar as the view of it is repeated over the course of the film.

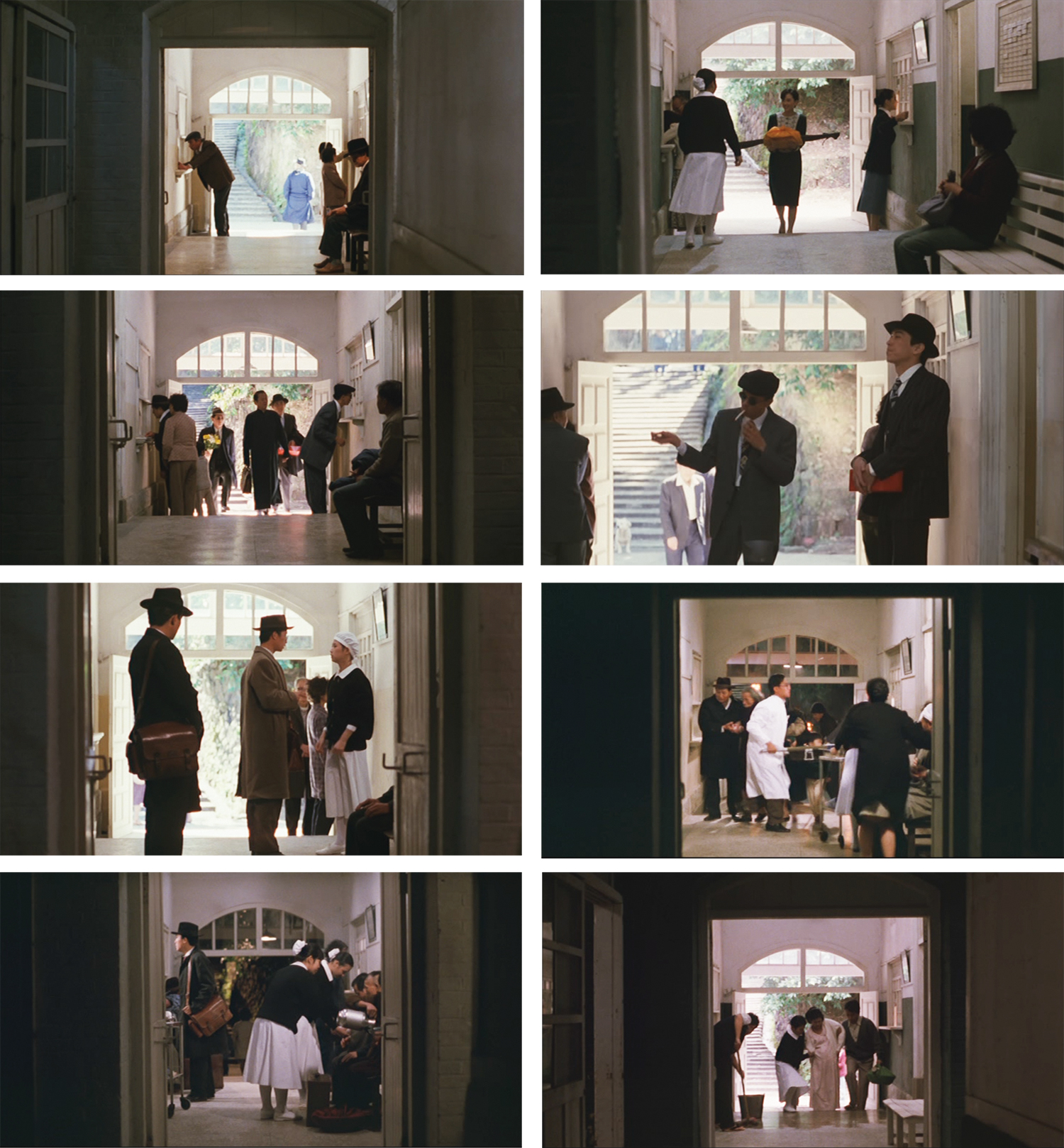

The two images in fig. 4 represent the first and last images of the hospital lobby. The image on the left sets up an axis that runs the length of the long lobby and occurs near the beginning of the film. Every subsequent shot of the lobby is located somewhere along this axis, moving back and forth depending on the scene. These shots are all static long shots (the only tracking shot of the film moves laterally). Interestingly enough, the first and last views of the entrance use exactly the same camera positioning—so far back on the axis that the camera is in a darkened backroom.

To give some sense of how extensive this is, the list below contains the eight predefined axes used by the seventeen shots of the film’s most extraordinary sequence. In the space of fifteen minutes, we see the family through the death of the Oldest Son, his funeral, the marriage of Wen-ching (Youngest Son) and Hinomi, the birth of their son, and finally the death of Hinomi’s brother. These axes are:

- Shrine room axis: shots 6, 8, 9; used twenty times in the film

- Bar hallway axis: shot 1; repeated twice

- Light table and hallway axis: shots 11, 16; repeated five times

- Street market axis: shot 10; repeated twice

- Dinner table and bedroom axis: shots 12, 15, 17; repeated fourteen times

- Distant bay axis: shot 14; repeated three times

- Funeral axis: shots 3, 4; repeated twice

- Hospital entrance axis: shot 13; repeated eight times

This principle of restricting the camera to a predefined axis is directly related to other aspects of Hou’s style in exceedingly complicated ways. If the stageline and the proscenium effect it creates is the cornerstone of classical montage—the imaginary line that organizes all cinematic space—then the camera axis replaces that organizing function in Hou’s narrative system. As we demonstrate below, this “uncinematic” shooting strategy produces playful variations of mise-en-scène and amplifies the powerful impact of the film’s violence.

One of Hou’s assistant directors, Angelika Wang, tells a revealing story related to Hou’s approach. She said that after a set was built, and before the director and cinematographer arrived on the scene, the crew would gather on the set and place bets on which axis the director would place his camera on. Even Hou was surprised to hear this story.

Geometricization of Space

Hou’s shots often display a spectacular geometricization of the mise-en-scène, revealing a fascination with graphic play. For example, in the main house the wall of windowpanes divides the movie screen into a field of rectangles (fig. 5). This view recurs throughout the film, often with people both in front of and behind the windows. He often foregrounds the intersecting lines of the windows and doorways by placing the characters behind them. The action continues smoothly while the composition undergoes rather extreme stylization, a stylization that can be appreciated in and of itself. In other rooms of the same house, windows are decorated with stained glass diamond patterns. These diamonds often provide the backdrop for dinners and discussions, and shift from one pattern to another depending on the room. Besides signaling location, they function on a level of graphic play from one scene to the next, signaling an appreciation of the frame as pure composition—a predilection that Hou shares with Japanese director Ozu Yasujiro.

This stylized mise-en-scène may be found in Hou’s earlier films as well. In these films, it is easily attributable to the Japanese architecture, which is naturally divided into squares and rectangles. However, by virtue of his consistency, it becomes clear that Hou is composing his shots with an unusual sophistication and under quite different rules. Hou’s composition constantly emphasizes the geometry of the architecture. Throughout the director’s work, human characters compete with squares, rectangles, and hexagons for attention. Finally, the geometricization of space in Daughter of the Nile (Ni luo he nu’er 尼羅河女兒, 1987), one of Hou’s most formally beautiful works, is more extreme than City of Sadness; there is no teleology at work in Hou’s oeuvre, only an orientation toward the perfectly refined composition and stylization.

Camera Movement

Nearly all camera movement in Hou’s cinema occurs in takes up to several minutes long. The few pans in this film generally sweep from one axis to another, from one familiar tableau to the next. Furthermore, in City of Sadness the camera position moves in the course of a shot only once: a slow lateral tracking shot when an old woman arrives at a meeting to mediate a dispute. The slow track splits a long take into two distinct tableaux (a hallway and a meeting room). Finally, camera movement is motivated by the actions of characters, so that despite this constant reframing Hou’s films contain an overwhelming sense of stillness. This stylistic effect greatly empowers Hou’s thematic use of still photography, which we discuss below. In fact, the style of the film is actually identified with still photography: the only point of view shots in the film are connected to the look of Wen-ching’s camera, for example when he shoots a farewell photograph of a teacher and his students.

Of all of Hou’s films, City of Sadness is probably the most severe in its restriction of camera movement. In subsequent films, he uses constant reframing, as well as pans that disregard the camera axes he used in previous scenes.

Delimitation of the Frame

Hou enhances the graphic possibilities of composition through the delimitation of the frame, another aspect of mise-en-scène directly linked to his restricting the camera to predefined axes and the geometricization of space. Figure 6 shows two striking examples from Summer at Grandpa’s. Both are views repeated throughout the film. They are photographed using 180-degree jumps over a staircase landing. The image on the top shows the landing cutting down the usable space for actors to the top half, and emphasizes the geometric qualities of the hexagonal window in the background. For the image on the bottom Hou pares down the narrative space to a tiny window.

The most striking example from City of Sadness is the hospital lobby of (see all the shots using this setting in fig. 8). The space is divided into four areas: the lobby itself, the contiguous rooms offscreen, the stairway outside the entrance, and a back room that the camera enters and departs. The graceful, arched doorway creates a second frame inside the film frame, and contains a partially eclipsed stairway that people ascend and descend, emphasizing the offscreen space above the top edge. At several points, the camera returns to the hospital lobby and is placed back in a darkened room; the dark walls of the doorway delimit the visible dimensions of the movie screen into an area one-sixth of its normal size, in effect creating a third frame. Furthermore, it is now a nearly perfect square. Not only does the space of City of Sadness become fractured into a graphic plane, but the size and shape of the screen itself (at least what is available to the narrative) varies. Hou’s other films use this frame-within-a-frame composition. From these examples, it becomes particularly clear that this works in tandem with geometricization to emphasize the graphic qualities of the image.

Ellipsis (and the Long Take)/Control (and Freedom)

Because of the long take’s close association with the theoretical assumptions of neorealism, any subsequent use of it makes for a deceiving representation of the real by duplicating the original mistakes of the neorealists. Most crucially, they emphasized the synthetic qualities of the long take while ignoring the contradictions posed by the inevitable use of ellipsis. To look at the temporal gaps between takes (of long or any length) is to acknowledge the artificial, constructed nature of the long take style. Thus, when Hou’s critics point out his “realistic” use of the long take, they inevitably refer to his style in terms of realism, rather than stylization and overt control.

By way of contrast, we will emphasize the consciously creative use of ellipsis in relation to the long take. For example, when the second brother insults a rival gang member in the club’s restroom and a fight breaks out, it seems to be completely contained in a sequence shot because the second shot is of a card game in what appears to be a different time and place. However, a few long beats after the beginning of the second shot, the fight erupts into the room and is broken up; the second brother lies wounded in his elder brother’s arms. Once again, the next (third) shot seems to begin a new sequence as the rival gang’s boss walks down a corridor, but the sounds of a fight fade into the background and now older brother bursts into the hallway only to be shot. The endings of both the first and second shots appear to contain an ending; however, they actually conceal an undecidable ellipsis that becomes evident only in retrospect. Every aperture seems to contain a surprise.

By making the temporal gaps between sequence shots of indeterminate length, Hou forces a curious instability into the image. One is never confident in the temporal or spatial coordinates at the beginning of a shot, forcing the spectator to rely heavily on the previous sequence shot until the who, what, when, and where of a shot/sequence is established. This constant need to ground a sequence shot in what came before makes elements of one shot’s time, space, narrative, and mood bleed into the next. Hou is well aware of this effect: “When I cut between scenes, I try to allow the unfinished atmosphere of the last shot to continue into the next” (David Kehr, “Director Makes Ordinary Life Extraordinary”). This has the effect of smoothing out the cuts between shots, making the film a distinctly amorphous experience. This plays into idealizations of the long take aesthetic as closer to reality, as a method that grants a measure of freedom to both the spectator and the actors (nonactors who are allowed to improvise their own dialogue). However, this effect is created by embedding the long take in a controlling, far from obvious structure, creating a subtle dialectic between freedom and control.

Long Shot/Close—up

In City of Sadness, the closest Hou’s camera approaches any character is from the chest up, what would probably be defined a medium close-up. It is a physical distance that translates into an emotional one as well. However, Hou’s films can be quite moving, and the lack of close-ups is (surprisingly enough) one of the reasons.

Medium close-ups of single characters are close enough to make facial expressions legible, but by keeping the camera away from the action, long shots emphasize the context among characters. By extension, this occasionally reflects a cultural emphasis on the family before the individual, deriving, in the last instance, from a long history of Confucian thought. This suggests that in American movies, our cultural obsession with individuality translates into a cinematic singling out by means of the close-up; narrative focus on a hero is complemented by the mise-en-scène. City of Sadness presents an alternative approach to mise-en-scène where, more often than not, the characters are seen (in long shot) in the context of other family members. In fact, the only true close-up of the film is of a photograph Wen-ching is touching up: a family portrait. Hou compounds his visual orientation toward the plural by diffusing the narrative attention among a number of characters. As in most of his other films, it is difficult to decide who the primary character is.

According to Hou, he began using long shots to cover for his nonprofessional actors. At the same time, he asserts that the long shot—combined with the long take—produces a special kind of image: “I’m not using the long shot just for the sake of the actors. A screen holding a long shot has a certain kind of tension, and for this you can’t find an alternative method to substitute. I realize I am confronted with a contradiction here” (Mart Dominic and Peter Delpeut, “A Man Must Be Greater Than His Films,” 16). It is difficult to provide an example of this effect, since it relies heavily on the accumulation of emotional resonance from shot to shot. At the same time, moving in for the close-up when Hinomi and Wen-ching learn of Hiromi’s death is unthinkable. Nothing is more devastating than watching nearly three minutes of their baby crawling around, oblivious to their tragedy (see fig. 20 in chapter 4). Likewise, the palpable tension in Hou’s long shots is crucial for energizing offscreen space and the violence it just barely contains.

Revelation of Spatial Relationships

Hou constructs his cinematic space through gradual, incremental revelation. Since each view is locked into a predefined axis, the overall sense of space builds slowly over the course of the film. At times, spaces that seem like separate locations are suddenly revealed to be adjacent. Only by actively perceiving visual cues can the spectator construct a more complex sense of the relationships between spaces. These visual cues consist of pans from one axis to another, as well as props or landmarks acting as spatial anchors that may be seen from more than one axis. The spatial relationship for two of the most highly used spaces in the film—the main entranceway with its porcelain vase and the shrine room—is hazy at best. The spectator knows they are in the same house; however, only late in the film does a discreet cut from one long take to another reveal they are adjacent rooms. Both spaces are familiar because Hou always uses the same camera angle whenever he returns to each room; that they are adjacent is evident only when Eldest Brother walks from one room to the other.

In this way, initially fragmented space is incrementally homogenized, until one should have a sense of any set’s layout by the end of the film. Hou’s gradual revelation of space, the variation from view to view as the camera is placed at different points along its axes, and the concomitant play of graphic forms serve to unify the film structurally while maintaining a quality of indeterminacy and fragmentation that contributes to the film’s dialogical properties.

Transitional Spaces

Hou’s use of transitional shots with vague connections to the diegesis prompts some critics to make comparisons to Japanese director Ozu Yasujiro (although, as we argue below, this comparison is dubious). Generally, these transitions are single long takes and consist of long shots of natural settings, such as the bay, the mountains, or a road switchbacking up a hillside. They provide a gentle punctuation between scenes, a little space to pause that adds to the film’s measured rhythm and quiet atmosphere. In terms of narration, they function in a variety of ways. The road transition usually occurs when a character begins a trip. The view of the bay defines the setting of Kee-lung, where the February 28 massacre began. They are also related to Hou’s creative use of ellipsis, for few of the shots are temporally marked. They imply some indeterminate passing of time, but it is rarely clear how much.

Shot—Reverse Shot

One of the most surprising restrictions Hou imposes on himself is his minimal use of the shot-reverse shot. Other aspects of his style factor in here—the long take, the refusal of the close-up—testifying to the interconnectedness of all these.

City of Sadness contains only six moments that could be considered the shot-reverse shot figure. Most of these are simply perfect 90-degree shifts around a dinner table, but as exceptions the shot-reverse shots often come at strategic moments that integrate other aspects of his style. A significant instance of this in City of Sadness is found in the wedding scene, which is particularly fascinating for formal reasons. Containing four long takes, this sequence is staged “incorrectly” by the standards of classical style, but it obeys the rules we have been discussing for Hou’s films. The shot plan in figure 7 shows the positioning of the camera for each shot.

The wedding party enters the room and begins the ceremony on the other side of the glass wall (shot 1); the couple faces the shrine, with their backs toward the camera. A reverse shot shows a “perfectly” composed view of the couple standing before the altar (shot 2). Because it is both a reverse shot and a closer view of the couple, the shot initially seems like a typical strategy for singling out protagonists, for encouraging our identification with them. However, every time the couple bows they drop nearly completely below the frame, revealing their family overseeing the ceremony in the background. The mundane reverse shot turns out to be a typical shot emphasizing the context of the family.

This is, in turn, followed by another reverse shot of the bowing couple, yet containing rather odd, “improper” composition (shot 3). Because shot 2 shows the bride and groom facing the left-hand side of the frame, classical rules would dictate that the reverse shot over their shoulders would basically duplicate the eye line: they would be placed on the right, looking left into the center of the frame. However, while shot 3 reverses the angle to a view of the couple’s backs, it is nudged to the right so that the groom is now edging into offscreen space and the bride looks left at the side of the frame. In the center of the frame the patriarch of the family sits, watching the proceedings with approval.

This reverse shot is “wrong” in that the camera is turned slightly too far to the right (thus cutting off the groom and allowing no on-screen space for the bride to look into); a classically composed shot would put the father to the left of the couple (in the space they face). On the other hand, it is quite correct in the context of Hou’s style in two ways. First, it emphasizes the domestic and familial circumstances in which the action takes place. The mise-en-scène focuses our attention on the father and his new daughter-in-law, expanding the narrative scope of the wedding to include the entire family; in other words, it emphasizes context rather than the individual.

A second, more compelling, reason it is not “wrong” relates to Hou’s peculiar penchant for snapping the camera onto the same axis every time he returns to a set. The reverse shot that follows shot 2 ignores the needs of classical narrative that would dictate we see the two main characters framed in a similar (centered) manner from each angle. Instead, it responds to Hou’s own rules, locking into the axis defined by shot 1, which “naturally” relegates the groom to offscreen space and the bride to the left-hand side of the frame. Furthermore, shot 4, the last shot of the scene, replicates the view of shot 1 and represents a perfect jump backward along the axis from shot 3. This scene violates the classical sense of narrative space, while it obeys the laws of editing intrinsic to Hou’s style.

Repetition

This is where all of the aspects of Hou’s style coalesce to form a wellspring of affective power. Because the camera sits on various points of an axis, the same view is repeated over and over through the film. The more important the space, the more often its image is repeated. This is responsible for much of the emotional effectiveness of Hou’s style because the shots come to resonate, both subtly and powerfully, with each other. As a view is repeated, a residue of action and emotion builds.

For example, consider the view of the hospital hallway (fig. 8). Here we see a band marching down the outside steps during the celebration of Japan’s defeat. Long separated friends reunite beneath its graceful, arched entrance. When the political situation turns sour and the violence of the February 28 Incident begins, wounded Chinese are carried through its portal . . . followed by an angry mob of Taiwanese. Later, we hear the radio broadcast of the Nationalist leader echo through the halls, assuring the country—with bold hypocrisy—that nothing is wrong. Not long after that, Hinomi crosses the hospital’s threshold to give birth to her son, and the emotions and memories associated with all this life, death, and pain coalesce.

The view of the shrine is one of the most highly charged in the film because of this narrative and visual repetition. The first time we see it, a celebration for the opening of the new family business is under way. After that, it is repeated in nineteen long takes, serving as the site of weddings, scoldings, feasts, reunions, and the mending of emotional and physical wounds. The table in the foreground serves as the site of countless meals, and tallies the toll the political sea changes take on the family. Fewer and fewer sons are alive to share meals, and in the devastating penultimate shot of the film only the patriarch and his shell-shocked son survive to eat together. As for the rest of the family, their absence is their presence thanks to this constant, poignant repetition.

This emotional residue is capable of charging “empty” shots as well: the last image of the film is simply the staid Chinese vase sitting below the diamonds of stained glass. Nothing happens. But the events that echo throughout that space infuse it with a quiet sadness.

The broad contrasts that these repetitions involve would be clumsy and ineffective had they been traditionally juxtaposed by means of montage. Instead, by virtue of their common placement in nearly identical mise-en-scène, they resonate across the vast temporal reaches of the narrative.

Violence . . . Seen and Unseen

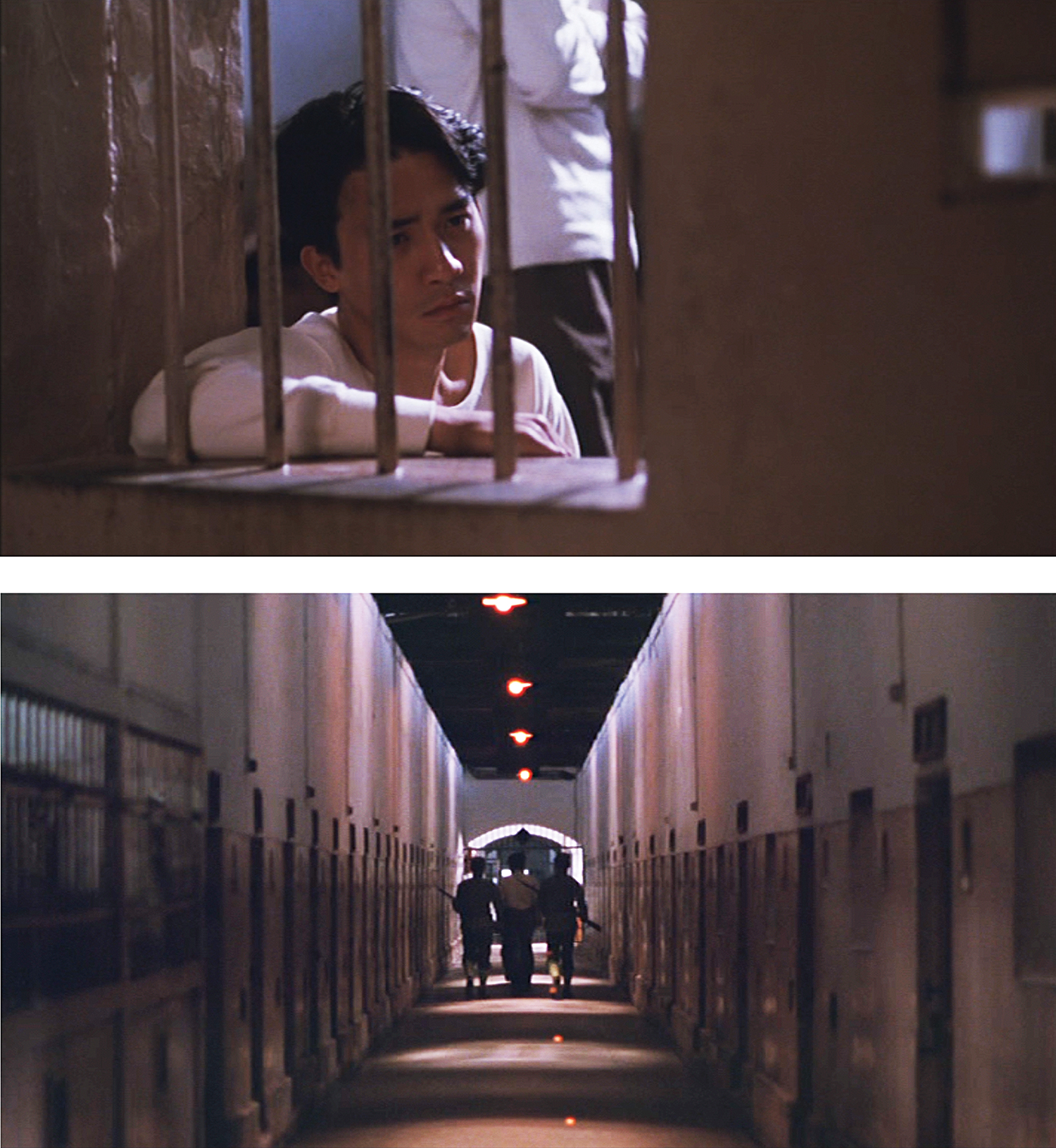

In one of the most astounding scenes of City of Sadness, Wen-ching sits in prison (fig. 9). KMT guards open the door and brusquely take a few men away. As their footsteps echo down what sounds like a long hallway, the camera lingers on the deaf Wen-ching, who broods silently behind a barred window. The footsteps stop, followed by the report of gunfire.

This execution—visceral for its suddenness and invisibility—does not register on Wen-ching’s handicapped body; he watched them go, but could not hear them die. It makes the next scene all the more disturbing, for the same soldiers return and take Wen-ching into the troubling offscreen space. This scene is the purest example of the (indirect) representation of violence in Hou’s films.

The centrality of this representation of violence, particularly in relation to Hou’s particular stylistic system and his narration of the nation, will concern this section of our analysis. This curiously reserved approach to violence informs all of Hou’s films. It is radically different than the ballet-like stylization of Hong Kong films, the cultivated precision of Japanese cinematic swordplay, or American cinema’s spectacularization and fetishization of violence through the use of close-ups, rapid cutting, realistic makeup, and special effects. Hou tends to pull away from the sometimes savage acts of his stories and show them from a distance.

This reticent approach is taken to an extreme in City of Sadness, where most of the acts of violence are pushed far away from the camera—often offscreen. When mobs of Taiwanese start beating Chinese in the wake of the February 28 Incident, we see fights in the distance, which are then shoved into the background in the shot of Hinoe watching in disbelief; then the violence is pushed entirely offscreen in the subsequent shot.

In another scene of retribution (fig. 3), Second Brother stands on a country lane, cut off from the waist down by the bottom edge of the frame (we do not yet realize that he’s hiding something in the offscreen space). Carriages arrive in the distance; when Second Brother runs toward them, the Japanese sword he was holding offscreen comes into view. We watch as he and his friends attack the men from the carriage in extreme long shot, moving on- and offscreen as they run behind the tall grass and buildings.

This strategic placement of violence just beyond sight may be found in other Taiwanese films. In “Hou Hsiao-hsien and Narrative Space,” Abé Mark Nornes has argued that Edward Yang’s delegation of violence to offscreen spaces serves as an organizing function. It should be remembered that Hou and Yang have worked closely in the profilmic spaces, both behind and before the camera. Indeed, Hou’s unusual portrayal of violent acts in extreme long shots is somewhat reminiscent of the fight on the lonely road at the end of Edward Yang’s Taipei Story. Here Hou himself (acting in the main role) is attacked and receives a stab wound that causes his character’s death.

At the same time, Hou also articulates this approach with other aspects of his style, making the use of offscreen violence his own. For example, in one of the first scenes of conflict, a knife fight breaks out in the nightclub’s hallway. Hou cuts in midfight to what appears to be one of his poetic transitional shots, which we have come to expect: a pair of rickshaws pull up to a peaceful town in extreme long shot. By this time we have learned that these pretty land- and cityscapes mark the ends of scenes and contain undecidable ellipses in time. A man emerges from one of the rickshaws and enters a building, while villagers mill around an open area gossiping. Thirty seconds into this minute-long shot, the fight from the previous scene bursts into the open area—into on-screen space. Hou masterfully builds up our expectations for a poetic transition shot introduced by a typically undecidable ellipsis, only to reveal that there was no temporal gap between the shots, that there was neither transition nor ellipsis.

Since the most violent act of the film, the February 28 Incident itself, occurs offscreen, it is crucial to examine more closely this relationship between violence and space. In this respect, Marsha Kinder’s elaboration of the iterative in cinema, in “The Subversive Potential of the Pseudo-Iterative,” is useful to understanding how this approach to violence relates to the film’s politics. The iterative refers to stating once that which happened multiple times. All films contain both iterative and singulative aspects. The classical style tends to emphasize its singulative characters, while relegating iterative aspects to mere background. On the other hand, a style like neorealism (or the early Taiwan New Cinema, for that matter) foregrounds the slippage between the two, because it is the typicality of its narrative that is important. The troubles of Vittorio De Sica’s singulative bicycle thief, for example, are meant to evoke the common experience of the entire nation’s poor.

In like manner, there is a constant, prominent slippage between the singulative family at the center of Hou’s narrative and the collective experience of Taiwanese between the twin pressures of the Japanese and the Nationalists. While a typical Hollywood film would focus on the family to the exclusion of larger political issues, City of Sadness centers on a single family to speak for every family, or the nation as family. The movement from the singular experience of the family to other levels often occurs in the mise-en-scène. Kinder notes, “The interplay between singulative event and the paradigm it represents is frequently played out spatially in terms of foreground and background” (7). An example in City of Sadness would be the scene mentioned above with Hinoe at the railway station. After Hinoe watches the indiscriminate beatings in the distance, the sequence ends with Wen-ching becoming the focus of a mob’s wrath.

Furthermore, Hou’s style offers a further, more peculiar, space of the iterative. Here the iterative is played out in terms of on- and offscreen space. In the prison scene we described at the beginning of this section, Wen-ching watches two anonymous men walk into offscreen space to their deaths, and then shortly thereafter he follows them down the same hallway. Throughout the film, we hear the seemingly endless repetition of “So and so has been arrested. So and so has disappeared,” over and over again. We see incidents of mob rule, police roundups, and searches as they affect the singulative Lin family; at the same time, the sounds of these types of violence performed against other families form a sonic backdrop as constant as a musical score. By initiating violence against the main characters onscreen, then relegating paradigmatic violence to the offscreen spaces, Hou cultivates the oppressive sense that this is happening across the entire island, affecting hundreds of thousands of families.

We would also argue that extratextual factors enter into the iterative. It must be remembered that every family in Taiwan has stories about how this turbulent time affected their own family. This personal history certainly constitutes a central reading code for the film; what happens to the Lin family is read through the experience of one’s own family memories and, by extension, the nation as a whole.

Hou has repeatedly claimed he did not set out to make a “political” movie, yet the decision to make a film about this period has wide-ranging political implications. Until City of Sadness was released, the subject of the February 28 Incident was strictly taboo and repressed from public discourse. Hou ran the risk of censorship, and strategically showed the film abroad before releasing it in Taiwan. After the Venice Film Festival prize, the threat of government censorship quickly died. Upon its release, it generated a healthy, furious debate, which Hou surely foresaw. He was doomed to satisfy no one, and he did not. The immigrants from the mainland and their descendants felt the movie let the Japanese off scot free, while portraying the actions of the KMT unfairly. Taiwanese, on the other hand, still reeling from the massacre of 2.28 and its bloody retributions, felt betrayed. They point out that the incident itself occurs offscreen, and that much of the violence shown is initiated by Taiwanese against mainlanders.

Hou both evades and addresses these issues through the use of the iterative and offscreen violence. Being the first media figure to broach the subject of the massacre, Hou was under enormous pressure in terms of how to represent the previously unrepresentable. Like other filmmakers working under conditions restricting their expression (for example, Kamei Fumio in wartime Japan, John Huston in wartime America, Sergei Paradjanov in the Soviet Union), Hou chose to speak indirectly. Pushing the most sensitive violence to the offscreen spaces—and multiplying the victims of that violence by invocation of the iterative—allowed Hou to bring this repressed, formative moment in the history of the nation into the open for the people in Taiwan to reflect upon its meaning for today.

While this film was in production, the government of Taiwan was containing social and political unrest in a high-handed way, despite the lifting of martial law. The film does not go for the jugular, but it certainly promoted movement toward healthy dialogue and freedom of expression. Taiwanese cinema presents a situation we’ve seen in many countries emerging from long periods of censorship and repression, adopting an ambiguous stance in the face of the authorities’ cold, pedagogical clarity. It is into this ambiguous space, through a quirk of timing, that the events of June 4, 1989, in Beijing inserted themselves, perhaps extending the iterative across space and time, for it was impossible to watch Hou’s film without thinking that Beijing was also a City of Sadness.

Hou and Ozu

While Hou Hsiao-hsien (1947–) and Ozu Yasujiro (1903–1963) are undoubtedly two of the great masters of world cinema, they are radically different directors. This did not stop many early critics from making facile comparisons, or even claiming that the Japanese director influenced Hou. This section investigates these claims to winnow out their differences as well as their similarities.

Stylistic Predilections

Ozu Yasujiro’s name is invoked regularly in discussions of Hou in both Taiwan and Japan, and among Western critics as well. As with neorealism it is a relationship begging for clarification. Few critics comparing the two directors attempted any real close analysis. They tended to base their comparisons on misunderstandings of both directors’ narrative strategies and on cultural essentializations (of self, other, or both). In fact, Hou did not see Ozu’s work until the late 1980s, after he already demonstrated his own peculiar approach to narration in films such as The Boys from Fengkuei and The Time to Live and the Time to Die.

Ozu may very well be a useful reference point for thinking about Hou’s achievement. It is easy to cite a few general areas of overlap: minimalism, a predilection for unusual self-restraint and systematization, as well as a fascination for the graphic qualities of the image. When he finally saw Ozu’s work he found a kindred spirit. This helps explain the subtle homage to Ozu in Hou’s 1995 Good Men, Good Women (Haonan haonü 好男好女; see fig. 10). In one scene the main character has a television playing in the background, and the film is Ozu’s masterpiece Late Spring (Banshun 晩春, 1949).

Self—Restraint

Ozu, like Hou, was anything but flashy. Indeed, for most critics who connect the two directors, this vague sense of self-restraint covering both their films probably constitutes the main basis for comparison. For Ozu, any effects that interfered with his own ideas about composition were cast away; he never zoomed and used only one dissolve (in the 1930 Life of an Office Worker [Kaishain seikatsu 会社員生活]). Because he also subordinated camera movement to composition, he did not use pans because they disturbed his framing. The few tracking shots he staged were designed to maintain a static composition (by moving along a road with a character, for example). When Ozu began shooting in color, he did away with camera movement altogether. As a general comparison, Hou and Ozu seem quite similar in terms of their self-restraint. However, when one looks at specifics the comparison breaks down. Most of Hou’s shots involve slight reframings, despite their apparent stillness. He occasionally trucks his camera, but unlike Ozu he does not attempt to maintain the same composition throughout the pan. Hou may show proclivities toward Ozu’s approach to cinema, but he is by no means as rigorous.

Transitions

Both Ozu and Hou insert curious forms of transitions between scenes and sequences. In Ozu’s case, they have been labeled “pillow shots” or “curtain shots” by various critics. Between scenes he would always place carefully framed shots of the surroundings to signal changes in setting, as well as for less scrutable reasons. Basically a hybrid of the cutaway and the placement shot, they are considered unusual for being quite extended, and apparently motivated primarily by graphic composition and pacing. Many critics have noted what seems to be a suspension of narration in Ozu’s transitions—to the point that some have called them extradiegetic. While Hou’s transitions evoke similar effects, a notable difference is that Hou’s are usually single shots. Ozu’s transitions involve multiple shots, and he often pivots around objects in the frame from shot to shot. In a transition near the beginning of Floating Weeds (Ukigusa 浮草, 1959) the camera revolves around a lighthouse, objects with the name of an acting troupe (a poster and banners), buildings, and people. Ozu’s transitions often involve such playful graphic matching of shapes and spaces through a series of shots, but Hou appears more interested in using his long-take transitions to create mood and narrative “breathing space.”

Low Angles

Ozu’s signature feature is the low angle, which is usually (but not always) shot with a camera set close to the ground. Every shot of the film uses it. While many writers have identified it as the point of view of a child, a dog, a god, or a person sitting Japanese style on tatami mats, David Bordwell, in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, convincingly argues that its position is actually proportional, meaning the height always changes as long as it stays lower than the object being shot. This makes all the lines in the frame follow generally the same pattern from shot to shot.

Hou does place his camera close to the ground at times, but this is almost exclusively in scenes set inside Japanese architecture. As a former Japanese colony, Taiwan has had many Japanese style buildings, or rooms with tatami floors. In City of Sadness Wen-ching’s home has several of these rooms, and scenes set here use a camera relatively close to the ground. Because people sit on the floor in these spaces, it only makes sense to lower the camera so it does not look down on them. In this sense, Hou is actually similar to most Japanese directors, who also place the camera at a low angle when shooting in traditional Japanese spaces.

360—Degree Spaces

Ozu’s most radical departure from classical style was his use of 360-degree space. By convention, Hollywood style dictates that the camera should stay within a 180-degree space to one side of the action. It is felt this will provide proper “screen direction” and a sense of homogeneous space. Ozu’s camera, on the other hand, orbits around the characters in a circle, using all 360 degrees. This can be found easily in any Ozu film. This produces a number of unusual effects that the classical style finds undesirable, such as graphic matching, but Ozu’s melodramas are so compelling that the engrossed spectator does not find them disrupting. When Hou breaks his scenes into more than one shot, he often shifts the camera a clean 45-degrees to one side (often around a table). However, these instances are extremely unusual and he generally sticks to the classical rule, leaving his camera on one side of the action.

Graphic Matching and Actors

An effect produced by Ozu’s jumping over the stageline is that actors facing each other seem to look off in the same direction. Ozu exploited the graphic possibilities of this by placing people in identical positions between (as well as within) shots. Ozu also favored a sitting position with the actor’s body “torqued” to face the camera. To many an actor’s frustration, their bodies were treated as objects to be carefully manipulated within the frame, and their lines had to be delivered with a minimum of emoting and movement. Ozu pushed this “graphic matching” between shots to notorious extremes; it is not unusual to see props such as beer bottles seem to skitter across tables or move closer to the camera to preserve their size and screen position from shot to shot. This is one of the most distinct aspects of Ozu’s style, and nothing close to it may be found in Hou’s cinema—with the exception of Café Lumière (Kohii jiko 珈琲時光, 2003), his homage to the Japanese director.

We’ve seen how Hou uses a geometricization of space that creates images comparable to Ozu’s indoor scenes. However, Ozu’s graphic matching relies on regular and relatively rapid cutting, the use of many shots within and between scenes. Furthermore, as Bordwell has argued, the basis of Ozu’s style is a modification of Hollywood’s shot-reverse shot, a figure that is the exception to the rule in Hou’s case. In fact, to our knowledge Ozu never used a sequence shot—he was surely disinclined to use them because they would interfere with graphic matching and other effects he loved.

Café Lumière as Homage

We can look to Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Café Lumière for the director’s own comment on his relationship to Ozu. This was a Shochiku production designed to celebrate the 100th birthday of the Japanese director. While they could have drawn on their own stable of reliable melodrama directors—for example, Yamada Yoji—someone at the studio had the good sensibility to bring in Hou Hsiao-hsien.

The result was pure Hou, with gestures to Ozu. The film starts with the old-style Shochiku logo in the Academy ratio the Japanese director shot in, followed by a train shot (fig. 11, upper right, an image that references Lumière as much as the Japanese director). The film’s second shot (lower left) establishes an axis through the main character’s apartment, and deploys a low camera angle that produces characteristically Ozu-like lines in the architecture. In a very long take, the character hangs wet clothing on a line, chatting on the phone about mundane matters of everyday life. She walks offscreen, leaving a clothesline full of clothes, an iconic Ozu image if there ever was one.

Then something very un-Ozu happens: the actor moves screen left and the camera pans with her (lower right). All this happens in the four-and-a-half minutes before the opening credits, and in only two shots.

These shots encapsulate the film’s dynamic between Ozu’s style and Hou’s style. The latter’s homage to the Japanese master presents us with an intertwining of these two low-key approaches to cinematic narrative. The train shot was taken from an angle Ozu never would have considered. The second shot featured Ozu’s iconography and camera positioning, but included pans and was nearly four minutes in length, a sequence in itself. There are strange ellipses, ubiquitous train travel and laundry, not to mention an (already pregnant) daughter who refuses marriage, but the similarities virtually end there. As James Udden writes, “One can argue that Café Lumière is true to the spirit of Ozu, but not the letter” (No Man an Island, 173).

Nation and Industry

This section on style has gone to great lengths to examine the manner in which Hou’s direction departs from the codes of classical style (or other major paradigms of film style, for that matter). It is important to note that there are both industrial and cultural bases for the comparison as well. The nexus for all these concerns seems to be the film critics, who provide a reading protocol that depends on Ozu to measure Hou’s difference to classical standards. Their desire to pin down Hou dovetails with larger ideological spheres, from neonationalism to orientalism depending upon the regional context.

By the late 1980s, Ozu’s position as an “international auteur” and one of history’s great film directors had been established through lengthy debates in Western film journals, books by Donald Richie and David Bordwell, and retrospectives throughout Europe, Asia, and the United States. In Japan, Ozu was the New Wave filmmakers’ emblem for everything wrong with Japanese cinema. However, in the 1980s his reputation was resurrected, and he swiftly became canonized as one of Japan’s greatest directors. This was largely due to the articles, lectures, speeches and books of Hasumi Shigehiko, one of Japan’s most powerful scholars (and one-time president of Tokyo University), as well as the director’s newfound recognition abroad. Nearly every year sees new works published on Ozu, and the works by Richie and Bordwell have even been translated into Japanese.

Hasumi was also one of the first writers to promote Taiwanese film in the early days of the Taiwan New Cinema (he also appears in a cameo in Café Lumière). For his own part, Hasumi was careful to avoid comparisons of Hou and Ozu, but other critics and audiences certainly were not. The connection helped pave the way for Hou’s popularity, and by the time City of Sadness was released, all of Hou’s previous films had been successfully distributed in Japan in theaters and home video. The theatrical releases included long runs in Tokyo’s finest theaters, where one often found standing-room-only crowds day and night. In the early 1990s Hou was even hired by a chemical firm (Nippon Shokubai) to make a commercial for domestic broadcast; the ad offered all of the iconography of Hou’s films—railroads, train tracks, laundry, long shots, and long takes—and certainly helped promote the release of several of Hou’s films in Tokyo.

The fact that Hou’s popularity would culminate in directing a television commercial—which would in turn be processed through a variety of media as news or promotion for his films—is emblematic of a shift in the discursive space of Heisei era Japan. At the end of the 1980s, Japanese turned their attention away from the West, and America in particular, and “rediscovered” Asia. Some critics spoke of a shift from a sen (line) to a men (surface) mentality, which is to say an abandoning of bilateral dependence upon the United States and a renewed consciousness of Japan’s Asian connections and the economic and cultural riches of its neighbors. While the former evokes the rhetoric of World War II, such as seimeisen (lifeline), the new men-tality is more expansive. This new pan-Asian consciousness coincides with massive postmodern consumption cycles, which shrewdly exploit differences through swift commodification, consumption, and expulsion in favor of the ever-new. In fulfillment of vague calls to “internationalization” (kokusaika), Japanese business collected objects from around the world (including films) and brought them to its center. Yoshimoto Mitsuhiro has argued that underlying this metropolitan veneer is a surging neonationalism that commodifies the foreign by erasing any disturbing otherness. We may see this very operation at work in the Japanese critics’ comparison of Hou and Ozu. By equating the two, they appeal to the postmodern pan-Asianism in circulation; some of the comparisons go so far as to point out Taiwan and Japan’s historically close relationship, again erasing the more unpleasant aspects of this history in a vague neocolonial nostalgia.

Although critics outside of Japan turn to Ozu for quite different reasons, in their attempt to rationalize Hou’s exceptional style they too turn to cultural explanations. For example, in a thoughtful commentary about how City of Sadness weighs upon his mind, Li Tuo (“Narratives of History in the Cinematography of Hou Xiaoxian,” 815) contrasts Hou to Zhang Yimou, and ponders what a truly Chinese film style might look like:

I once again think of Raise the Red Lantern (Da hong deng long ghao gao gua 大紅燈籠高高掛, 1991). It is evident that Zhang Yimou gave his all in making this film. . . . But if we peer through the dazzling light created by the various elements of this film’s design to view the internal drama, anyone familiar with the traditions of Hollywood can easily see that this film is an exquisite copy of a Hollywood film. To copy Hollywood, of course, is not unusual. Film directors all over the world, motivated by all kinds of reasons, are doing just this. But if one puts a layer of artistic Oriental wrapping on the exterior of this copy and therefore believes one has created a Chinese film, then we can consult Hou Hsiao-hsien’s film to raise a question: in whose eyes is Raise the Red Lantern a Chinese film?

He suggests that the loose narration of City of Sadness may provide a route to define what a Chinese film style might look like, but leaves the difficult task of specificity to future writing or other industrious critics. Formulating the difference is relatively easy; explaining it is something else again. Some Western critics have not shied away. In her description of a visit to the City of Sadness set, Georgia Brown writes in “Island in the Mainstream”:

Sometimes a figure sits in the middle distance, internally absorbed, while in the rest of the frame, various others are in motion, carrying on some mundane business, creating a Taoist-Confucian dialectic between depth and surface, passive and active. The effect also suggests the mind’s internal play, tiers of experience, worlds within worlds.

This brand of orientalist mystification is typical, and one senses it in many of the comparisons between Hou and Ozu. For Western critics, the two directors share some kind of Asian sensibility that translates into their films (by virtue of colonial legacies or vague tropes of Asian sensibility). For Japanese, it is this and more; the popularity of both Hou and Ozu coincides with a resurgence of nationalism paired with intense postmodern consumption and appropriation of Japan’s Asian others and thus, the fact that all his work is available in every format—including television commercials—should not be surprising.

In any case, the link to Ozu has proven fruitful for promoting Hou’s films. The prestige of Ozu as one of film history’s great auteurs evidently rubbed off on Hou. Combined with tropes of nationhood, Asian affiliation, and Chinese-ness, Hou’s difference is tenuously grasped, celebrated, commodified, and consumed. Now is the time to move on to new perspectives.