London in Machyn's Time

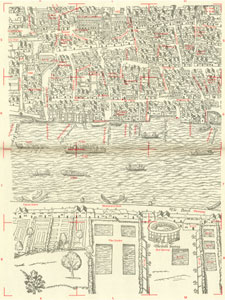

London in Machyn's day. Detail from the “Copperplate Map” (ca. 1577). From Adrian Prockter and Rober Taylor, The A to Z of Elizabethan London (London, 1979). Used by permission of the London Topographical Society.

In the middle of the sixteenth century, London was crowded, pestilential, and fascinating. People flocked there to gain riches, and Henry and Christopher Machyn were among the most successful of these migrants from the country. Remarkably enough, they survived quite a long time: Christopher lived some thirty years in the City, Henry more than forty. Most newcomers were not so fortunate.

By modern standards, London was small. The Venetian ambassador in 1554 estimated the population at 180,000, but more precise examination of the historical record suggests that the population was less than half that number. What made London seem so large was that it was built upward; tenements of several stories were nearly everywhere, and some of the streets were merely passageways only the width of a pedestrian's outstretched arms. The entire City occupied a space little more than a mile square. Outside the City walls were fields and gardens; inside were merchants beginning to look outward to markets for their products abroad.

The “Copperplate Map” shows the City in the decade during which Henry Machyn wrote. As Prockter and Taylor, editors of the atlas containing this map, show, there is remarkable detail in the representation: “garden wells, rowing boats, weathervanes, wine barrels, dogs, and laundry baskets are discernible.” One can see the minute details of the gates in the City wall over which the decaying heads and limbs of executed persons were so frequently displayed (as noted by Machyn). A point of reference was “London Stone,” thought to be put in place by the Romans to mark the center from which distances would be measured across Britain. Machyn mentions it often—for instance, the wife of the Bull's Head tavern located beside it was punished for being a bawd (June 12, 1560).

The Tower of London, St. Paul's Cathedral, and London Bridge were the largest and most important landmarks. All of them are mentioned frequently in Machyn's Chronicle. Transportation by water was the usual way of traveling between the Palace of Westminster and the City, but shorter trips across the Thames—for instance, to the bull baiting ring south of the City—were made by small boats and wherries. Navigating under London Bridge when the tide was changing was perilous, since the openings between the piers were small and held back the water. Machyn mentions occasions in which prominent persons carelessly conveyed were drowned there “by folly” (August 10, 1553). Games might be played outside the City, and those involving titled persons were noted in the Chronicle. On January 18, 1559, there were “great joustes” at the tiltyard, with the Duke of Norfolk making a notable appearance. Nonetheless, it was at the wharves on the waterside where the bustle of London was most apparent. More and more during Machyn's time, the City was becoming the great port through which goods were imported and exported.

In all its commercial bustle, London was the most linguistically various place in Britain, and Machyn frequently takes note of “foreigners.” The wife of the Bull's Head tavern was punished for providing sexual services to them. Frenchmen, Spaniards, Flemings, and the Dutch are noted in the Chronicle and are often shown in an unfavorable light. Scots regularly appear in it. People are identified by place, such as Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Oxfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshire, and other locations where a distinctive variety of English was employed. Though many years in London from his origins in Leicestershire, Machyn retained his youthful habits of speech (as Axel Wijk and Derrick Britton have documented), and doubtless many other migrants did too, producing a democratic welter of speech. And Machyn stayed put. There is no evidence in the Chronicle that he ever left the neighborhood of London, even to follow the funeral processions of prominent persons who were to be buried outside the metropolis. As Samuel Johnson would say two hundred years later, “he who tires of London, tires of life.” Machyn never tired of it.

A brief time line of events important to Machyn will introduce readers to the fascinating detail of the Chronicle. (Dates in parentheses direct attention to Chronicle entries in which these events are mentioned.)

| February 18, 1516 | Mary, daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, is born in Greenwich. |

| September 7, 1533 | Elizabeth, daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, is born in Greenwich. |

| January 31, 1547 | Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, is declared protector by the Privy Council. Royal powers were exercised under his command in the name of his nephew, Edward VI, then ten years old. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour. |

| February 20, 1547 | Edward VI is crowned. |

| July 1, 1550 | Machyn begins to keep his chronicle of events. |

| March 1551 | Arden of Feversham is murdered in a conspiracy led by his wife and her lover. The retribution is immediate and horrifying: three hanged; two burned; one hanged, drawn, and quartered. A generation later, a play would be performed based on these events; it was formerly attributed to Shakespeare. (March 14) |

| January 22, 1552 | Edward Seymour is beheaded. |

| July 6, 1553 | Persuaded to pass over the claims of his half sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, to the succession, Edward declares Jane Grey as his successor. He dies from tuberculosis at fifteen years of age. Machyn reports the rumor that he had been poisoned. (July 6) |

| July 9, 1553 | Jane Grey, the great-granddaughter of Henry VI, is proclaimed Queen, and a great celebration follows on the next day. (July 9–10) |

| July 19, 1553 | Mary is proclaimed Queen. (July 19) |

| April 23, 1554 | Philip, the King of Spain, is made a knight of the Garter. (April 23) |

| July 25, 1554 | Philip and Mary are married. |

| September 1554 | Mary is thought to be pregnant. |

| February 12, 1554 | Jane Grey is beheaded in the Tower of London at just seventeen years of age. Machyn makes no entry recording it. |

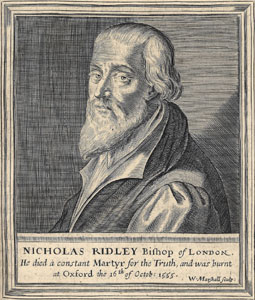

| October 15, 1555 | Bishops Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley are burned. |

Portrait of Bishop Nicholas Ridley. From Thomas Fuller, The Holy State (Cambridge, 1642). Special Collections, Hatcher Graduate Library, University of Michigan.

| March 21, 1556 | Archbishop Thomas Cranmer is burned. |

| August 10, 1557 | Spanish and English troops are defeated by the French at the battle of St. Quentin. |

| January 6, 1558 | French troops seize Calais from the English. |

| November 16, 1558 | Mary dies. |

| January 15, 1559 | Elizabeth I is crowned in Westminster Abbey. |

| 1561 | The first English tragedy, Gorboduc, by Thomas Sackville and Thomas Norton, is performed. |