The Hand of Hope: A Coproduced Culturally Appropriate Therapeutic Intervention for Muslim Communities Affected by the Grenfell Tower Fire

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

The literature indicates that ethnic minority and faith groups are under-represented in therapy services, report higher levels of dissatisfaction with mental health services, have higher disengagement rates, and poor recovery rates compared to the general population. This service evaluation explores the barriers encountered in accessing professional psychological help for a group of bereaved British Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) Muslim women who were affected by the Grenfell Tower fire[1]. A trauma-informed culturally appropriate faith-informed therapeutic group intervention, called the Hand of Hope, was coproduced with the community to address the barriers reported and to improve access to mental health services, and service experience for Grenfell-affected Muslim MENA communities who were not engaging with services. Two Hand of Hope therapeutic group interventions were piloted and mixed methods service evaluations were conducted which included focus groups and outcome measures. A thematic analysis was conducted. The findings indicated that participants were requesting informal culturally appropriate faith-informed therapeutic interventions. The service evaluation findings indicated that an informal, coproduced, culturally appropriate, and faith-informed therapeutic group intervention encouraged engagement and retention of MENA Muslim participants who previously held negative attitudes toward therapy; it challenged the stigma attached to mental health and seeking therapy; it improved the participants’ attitude toward therapy, and it increased the uptake of participants and their children accessing therapy. The findings also indicated reduced distress and improved service user experience, psychological and social wellbeing, trust, stabilization, emotional regulation, resilience, and coping. The implications of these evaluations and the relevance of the findings to mental health are considered.

Keywords: Arab, barriers, community engagement, coproduction, culturally sensitive therapy, disaster, ethnic minority, mental health, Middle Eastern and North African (MENA), Muslim, psychosocial intervention

Introduction

British government initiatives and the National Health Service (NHS) frameworks highlight the mental health needs of ethnic minority groups as a priority in the provision of appropriate mental health services in the United Kingdom (UK; Department of Health [DoH], 2005; Hamid & Furnham, 2013). Evidence suggests that Muslim communities are under-referred and under-represented in therapy services and have considerably poorer recovery rates compared to the general population (Mir, Ghani, Meer, & Hussain, 2019). Similar patterns were found for ethnic and religious minority groups nationally (Carter, 2017, cited in Mir et al. 2019), who also report higher levels of dissatisfaction with mental health services, and are more likely to disengage from mainstream mental health services possibly leading to deterioration in their mental health (Arday, 2018; Naz, Gregory, & Bahu, 2019).

Studies have found the following were barriers for ethnic minority individuals to accessing mental health services in Western countries: lack of culturally sensitive services (Arday, 2018; Grey, Sewell, Shapiro, & Ashraf, 2013; Mind 2013a); inadequate recognition of or response to the mental health needs of ethnic minority groups, cultural naivety (Arday, 2018; Grey et al., 2013; Memon et al., 2016; Mind, 2013a; Woods-Giscombe, Robinson, Carthon, Devane-Johnson, & Corbie-Smith, 2016); therapists not taking into account how therapy interacted with the client’s religion/spirituality (Mind, 2013a); language barriers and poor knowledge of mental health and available services (Abu-Ras, 2003; Arday, 2018; Memon et al., 2016); confidentiality concerns (Hamid & Furnham, 2013; Youseff & Deane, 2006); lack of trust, cultural mistrust of institutions, hierarchical relationships between service users and healthcare providers, and fears of disclosure due to concerns of being misunderstood or misinterpreted by healthcare providers (Arday, 2018; Keating & Robertson 2004); experiences of discrimination from healthcare providers (Arday, 2018; Keating & Robertson 2004; Memon et al., 2016); and shame and stigma associated with mental health problems (Alhomaizi et al., 2017; Arday, 2018; Pilkington, Msetfi, & Watson, 2011; Woods-Giscombe et al., 2016).

Shame and stigma associated with mental health problems were found to be a major barrier to accessing mental health services for those with Muslim Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) origins in Western countries (Abu-Ras, 2003; Alhomaizi et al., 2017; Aloud & Rathur, 2009; Youssef & Deane, 2006) and in the Middle East and North Africa (Gearing et al., 2013; Kadri et al., 2004; Rayan & Jaradat, 2016). Research has found that British Arabs and Muslims have a more negative attitude toward seeking professional psychological help compared to British Caucasians (Hamid & Furnham, 2013). Arabs (Abu-Ras, 2003; Al-Krenawi & Graham, 2011; Youssef & Deane, 2006) and Muslims (Pilkington et al., 2011) were found to have high levels of shame and stigma. This increased stigma was related to a lessened intention to accessing help or services for mental health difficulties, which Youssef and Deane (2006) found was attributed to strong cultural prohibitions on exposing any personal or family matters to outsiders.

Culture and faith are intrinsic to the formation of beliefs and ways of healing concerning mental health and illness (Fernando, 2010, 2014). This has been found to define acceptable responses to mental health problems and appropriate coping mechanisms, which influences minority groups accessing mental health services (e.g., Hamid & Furnham, 2013; Memon et al., 2016), and may directly lead to individuals preferring alternative means of coping.

Cultural and religious modes of coping

Cultural traditions and religious rituals can provide a protective function, and in the context of collective trauma have been found to restore community resilience and reduce distress (Kirmayer et al., 2009; Somasundaram & Sivayokan, 2013; Wilson, 2007). This includes the use of traditional healing practices, such as the following examples in particular communities: ancient Tamil folk arts (Koothu; Somasundaram & Sivayokan, 2013), Opari (lament; Duran, 2011) in Sri Lanka, oral storytelling among Aboriginal communities (Kirmayer et al., 2009), and sweat lodge purification ceremonies among Native Americans (Wilson, 2007).

Religion and spirituality have been found to be associated with better mental health, improved wellbeing, recovery, and coping with stress (e.g., Bonelli & Koenig, 2013; Bonelli, Dew, Koenig, Rosmarin, & Vasegh 2012; Koenig, 2012; Webb, Charbonneau, McCann, & Gayle, 2011). It is important to distinguish between types of religious coping: ‘negative religious coping’ is when a person feels punished or abandoned by God or unsupported by their religious community, and this coping is associated with increased depression, anxiety, and psychological distress (e.g., Ano & Vasconcellas, 2005; Dein, 2018; Dew, Daniel, Goldston, & Koenig, 2008; Pargament, Tarakeshwar, Ellison, & Wulff, 2001). In comparison, ‘positive religious coping’ (e.g., benevolent religious appraisals) is the use of an internalized spiritual belief system to provide strategies that promote hope and resilience, and is associated with positive psychological adjustments to stress, reduced levels of depression, anxiety, distress, and improved mental health (Ano & Vasconcellas, 2005; Dein, 2018; Koenig et al., 2001; Pargament et al., 2001).

Religion is a central component of many people’s lives; it can provide a cognitive framework that individuals use to interpret and cope with traumatic events and reduce distress by engendering a sense of purpose and meaning (Hammad & Tribe, 2020a; Peres, Moreira-Almeida, Nasello, & Koenig, 2007). Meaning-making can be a component of trauma recovery and aids adaptive coping with traumatic events (Hammad & Tribe, 2020b; Weathers, Aiena, Blackwell, & Schulenberg, 2016). Indeed, religion has been found to foster resilience and aided coping with collective trauma and loss such as war and protracted political conflict in studies of Arabs and Muslims (e.g., Hammad & Tribe, 2020a; Nuwayhida, Zurayka, Yamouta & Cortas, 2011; Salem-Pickartz, 2009; Thabet, Dajani & Vostanis, 2013; Thabet, Elhelou & Vostanis, 2015). Spirituality and positive religious coping have been associated with reduced psychological distress among survivors of war, community violence, sexual violence, child abuse, domestic abuse (Bryant-Davis & Wong, 2013), and natural disasters (MHum, Bell, Pyles, & Runnels, 2011). Religion was found to be a protective factor for deleterious psychological effects, and a resource that aided coping, meaning-making, acceptance of loss and the grieving process for bereaved Malay Muslim parents whose children had been killed in a traumatic manner (Hussin, Guàrdia-Olmos, & Aho, 2018).

Culturally adapted psychological interventions

Culturally sensitive interventions can enhance engagement and retention of service users (Cardemil, Kim, Pinedo, & Miller, 2005). It can help address the multiple and complex interplay of barriers that ethnic minority and faith groups encounter in accessing psychological support. Culturally appropriate interventions for mental health are promoted by policy bodies internationally (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2011; World Health Organization, 2013). The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC, 2007) Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings, developed by the United Nations (UN) and over 200 non-UN humanitarian organizations, encourage the use of culturally appropriate interventions and utilizing cultural and spiritual/faith-based resources that promote wellbeing and help people to cope and recover from disasters. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) incorporated religion/spirituality into their assessments and interventions as part of their mental health and psychosocial support programme (Quosh, 2013). Yet, trauma-informed psychological interventions incorporating religion and indigenous forms of healing are few (e.g., Akinsulure-Smith et al., 2009; Stepakoff, 2007).

Incorporating religious beliefs into psychological therapy is associated with positive outcomes (Mir et al., 2015). A meta-analytic review of 31 studies demonstrated that spiritual or religious adapted psychotherapy can effectively benefit clients with psychological problems such as stress, anxiety, depression and eating disorders (Smith, Bartz, & Richards, 2007). Religious-based psychological interventions for depression were found to result in faster symptom improvement compared with non-religious based psychological interventions or control groups, in five out of eight randomized controlled trials (Koenig, 2009). Randomized controlled trials have found that religious or spiritually informed mental health interventions reduced anxiety more than a standard intervention or control condition (Koenig, 2012).

Meta-analyses show that culturally adapted psychological interventions are typically more effective in improving mental health outcomes (e.g., Benish, Quintana, & Wampold, 2011; Griner & Smith, 2006; Hall, Ibaraki, Huang, Marti, & Stice, 2016; Smith, Domenech Rodríguez, & Bernal, 2011; Soto, Smith, Griner, Domenech Rodríguez, & Bernal, 2018). Similarly systematic reviews found that culturally adapted psychological interventions were effective for ethnic minority groups (e.g., Bhui et al., 2015; van Loon et al., 2013). A recent meta-analytic review of 99 studies, comprising 13,813 ethnic minority participants, found that when interventions are specifically aligned with the client’s culture, there is greater client engagement in therapy and better mental health outcomes and that the efficacy of an intervention increased as more cultural adaptations were applied (Soto et al., 2018). Similar findings are noted in other meta-analyses (Griner & Smith, 2006; Smith et al., 2011); mental health interventions tailored to a specific ethnic/racial group were four times more effective than interventions targeting a variety of cultural groups (Griner & Smith, 2006).

Rathod and colleagues (2018) conducted a review of meta-analyses on culturally adapted mental health interventions. The review highlighted that there is value in cultural adaptations. However, the review highlighted various issues with the meta-analyses including a lack of methodological rigor, small sample sizes, mixed ethnic and diagnostic samples, limited description of the adaptation process, a lack of systematic approach to cultural adaptation, and incomplete data. Their review also highlighted a lack of standardized universally accepted frameworks for cultural adaptation of interventions and difficulties in identifying which component of cultural adaptation is effective and for which population.

Culturally adapted psychological interventions for Muslims

A study in Malaysia on depression outcomes found that highly religious Malay Muslim clients affected by bereavement and grief who received psychotherapy with a religious perspective demonstrated faster and significant improvements which were maintained at six months follow-up in comparison to the control group who received secular psychotherapy (Azhar & Varma, 1995). The religious psychotherapy included discussions of religious issues specific to the clients (e.g., reading of verses from the Qur’an and Hadith, encouragement of prayers) in a collaborative cognitive behavioral approach. Other studies in Malaysia also found that religious-based psychotherapy rapidly improved symptoms of depression and generalized anxiety (Razali, Hasanah, Aminah, & Subramaniam, 1998; Razali, Aminah, & Khan, 2002). Azhar, Varma, and Dharap (1994) found Malay Muslim clients with generalized anxiety disorder had faster symptom improvement compared to individuals who only received medication or secular psychotherapy (Azhar, Varma, & Dharap, 1994). Hook and colleagues (2010) found spiritually/religious-informed psychological interventions as an additional intervention can help improve depression outcomes for Muslim clients.

Walpole, McMillan, House, Cottrell, and Mir’s (2013) systematic review of interventions for Muslims experiencing depression indicated the lack of published research in this area and the poor quality of available research studies. Their review highlights a wide range of factors to consider when providing interventions for depression for Muslims: causal beliefs, the role of faith in interventions, and the potential need to make adaptations in terms of therapeutic style. Mir and colleagues (Mir, Kanter, & Meer, 2013; Mir et al., 2015, 2019) culturally adapted a behavioral activation (BA) intervention for depression for Muslims; the intervention focused on utilizing positive religious coping as a resource for clients and integrating religious scriptures to enhance BA concepts and strategies. The study found that it improved access to psychological services and reduced depression for Muslim service users in the UK (Mir et al., 2019). Integrating Islamic teachings that promoted physical activity, compassion, self-management, and dispelling cultural myths into a culturally adapted pain management intervention was found to improve depression, anxiety, and self-efficacy in the UK (Bradford Teaching Hospitals, NHS Foundation Trust, and In Health Pain Management Solutions, 2018).

Service context

The Grenfell Tower fire that took place in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC), London in June 2017 was one of the largest modern disasters to affect the UK; 72 people died. People experienced significant displacement and lost their loved ones, families, friends, neighbors, homes, possessions, community, and sense of safety. The statistics gathered by the Grenfell police investigation and Grenfell United[2] indicate that 70 percent of the people that died in the Grenfell Tower fire tragedy were Muslim (Grenfell United, personal communication, September 19, 2018). A sizable population of ethnic minority and faith groups live in RBKC (2010a, 2010b) with estimates as high as 1 in 12 in the borough identifying as Muslim (RBKC, 2010b). Arabic is the second most common language spoken in the borough after English (RBKC, 2010c).

A gap in the provision of culturally appropriate support was identified, following feedback from some sections of the Grenfell-affected ethnic minority and faith communities requesting culturally appropriate, faith-informed therapeutic support. In response, the “Together For Grenfell” project was established, which involved community consultation to inform the needed response, and collaboration between statutory services and local third-sector community organizations to improve access to mental health services and improve service provision for Grenfell-affected ethnic minority and faith communities. The literature highlights the importance of community consultation, community engagement, and partnership in the development and delivery of mental health services (Bhui et al., 2015; DoH, 2009; Lane & Tribe, 2010; NICE, 2008; Perry, Gardener, Oliver, Çiğdem, & Özenç, 2019; Thompson, Tribe, & Zlotowitz, , 2018). Local organizations are often the first point of contact for ethnic minority groups in need (DoH, 2009); they hold valuable knowledge concerning the health needs of the communities they serve (DoH, 2009; Lane & Tribe, 2010; Perry et al., 2019). Through the Together For Grenfell partnership, a collaboration between NHS Grenfell Health and Wellbeing Service (GHWS), a third-sector community organization (Al-Hasaniya Moroccan Women’s Centre), and Grenfell-affected community members was established to coproduce a culturally appropriate faith-informed therapeutic group intervention called the ‘Hand of Hope’ (‘Yed al-Amal’ in Arabic). The goal was to provide support for bereaved MENA Muslim women affected by the Grenfell Tower fire tragedy. Al-Hasaniya Moroccan Women’s Centre is a third-sector organization providing a range of health/wellbeing-related services to Moroccan and other Arabic-speaking communities in RBKC, West London. The GHWS is part of Central North West London (CNWL) NHS Foundation Trust and was established as part of the disaster response to the Grenfell fire tragedy. It consists of an adults, children, and young people’s service and outreach team offering a range of therapies and support to people affected by the Grenfell Tower fire tragedy.

Aims of the service evaluations

There is a lack of research on evaluating interventions that involve community engagement, partnership working with communities (Thompson et al., 2018), culturally sensitive interventions focused on coping skills and wellbeing (Hall et al., 2016), and faith-sensitive therapies for religious minority groups (Mir et al., 2015). There is a paucity of research on identifying the barriers encountered in accessing mental health services and culturally appropriate psychological interventions for MENA populations, as well as Muslim populations from these ethnic groups in the UK. There is also a lack of research on culturally adapting therapy for the Muslim community in general (Mir et al., 2019). The service evaluations were conducted to help address the gap in the literature for this client group. Two Hand of Hope therapeutic groups were coproduced at different time periods to reflect the different stages and difficulties clients encountered post-Grenfell. A service evaluation is provided for each Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention.

The aims of the Hand of Hope groups and service evaluations were:

- To try to understand and address the barriers a group of British MENA-origin Muslims encountered in accessing mental health services.

- To coproduce a culturally appropriate therapeutic group intervention utilizing culturally appropriate modes of coping with trauma and loss that is responsive to the needs of the Grenfell-affected MENA Muslim communities.

- To assess the impact and participant experience of a coproduced culturally appropriate faith-informed therapeutic group intervention for a group of bereaved MENA Muslim Grenfell-affected participants, and whether it improved access to mental health services for the participants and their children aged under 18.

Method

Cultural adaptation and theoretical framework

In this paper, we discuss two Hand of Hope therapeutic group interventions which were piloted at different time frames—10 months and 22 months after the fire. In this section, we discuss adaptations we made to address the reported barriers and the framework and approaches we used to coproduce a culturally appropriate intervention. The Hand of Hope therapeutic group interventions adopted an integrative therapeutic approach utilizing community psychology, cognitive-behavioral aspects, relational/interpersonal, narrative, expressive/humanistic therapies, and Western group therapy principles. A combination of bottom-up (Hwang, 2009) and top-down (Bernal, Bonilla, & Bellido, 1995) approaches were used to create a culturally appropriate intervention. Hwang’s (2009) formative method for adapting psychotherapy (FMAP) utilizes a bottom-up approach consisting of collaborating with community stakeholders to develop ideas to adapt the therapy, and involves five phases that target developing, testing, and reformulating therapy modifications. Bernal and colleagues (1995) outline an Ecological Validity Model consisting of eight dimensions of culturally adapting interventions for ethnic minority groups using a top-down approach: a) language (e.g., offering therapy in the client’s preferred language); b) persons (e.g., matching client and therapist on salient variables to enhance therapeutic alliance, such as culture/race/language); c) metaphors (e.g., use of cultural expressions and concepts); d) content (e.g., applying cultural knowledge about traditions, customs, and values); e) concepts (e.g., intervention concepts consistent with culture); f) goals (e.g., support of client’s desired outcomes); g) methods (e.g., cultural enhancement of intervention methods); and h) context of the intervention/services (e.g., considering impact of client’s socio-political economic context).

The Hand of Hope therapeutic group interventions were informed by Herman’s (1992) three phase (non-linear) model of trauma recovery. The first phase of recovery involves safety and stabilization (e.g., stabilizing symptoms and building trusting relationships). The second phase involves remembrance and mourning (e.g., expressing emotional impact of and processing trauma and loss). The third phase focuses on reconnection (e.g., reintegration and reconnecting with people, meaningful activities, and other aspects of life). A community psychology approach was adopted that aimed to meet the mental health needs of ethnic minority and faith groups that were not engaging with mental health services by trying to address the reported barriers to improve access, and improve service user experience by coproducing and tailoring therapeutic interventions to meet their cultural and faith needs following collective trauma and loss. The IASC (2007) Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings endorse community consultation in the development and delivery of services, the activation and strengthening of social support networks, and the use of cultural and faith-based healing practices; these recommendations informed the development and delivery of the Hand of Hope therapeutic group interventions.

In many cultures, food and social connectedness is central to the grieving process. Following the initial stages of bereavement in MENA cultures, the bereaved generally do not cook for themselves, people will visit to offer their condolences and bring cooked dishes to feed the bereaved family. In the MENA cultures, feeding others is a deeply symbolic gesture of care and love. Cultural healing practices and collective cultural coping strategies in many MENA cultures include oral storytelling—‘hikaya’ (Atallah, 2017; Zarifi, 2015), hospitality and communal gatherings over food (Abi-Hashem, 2006; Hammad & Hamid, in press; Zarifi, 2015), and traditional arts connected to cultural heritage such as communal embroidery (Zarifi, 2015). These cultural healing practices are used during times of collective trauma and loss. Hikaya involves people bearing witness to each other’s stories in a supportive environment where the sharing of tales of sorrow, joys, life, memories, and linking their past to their future takes place (Zarifi, 2015). In many MENA cultures, the processing of collective trauma and loss and distress is typically done collectively in an informal supportive manner focused on a concrete shared activity connected to cultural heritage (Hammad & Hamid, in press). Cultural healing practices were central features of the Hand of Hope therapeutic group interventions and were used to (1) promote stabilization; (2) support remembrance and mourning; and (3) promote reconnection—reconnecting with people, meaningful activities, and other ordinary aspects of life, as per Herman’s (1992) trauma recovery model.

Supporting cultural healing practices can increase psychosocial wellbeing for many disaster-affected people (IASC, 2007). Ignoring such healing practices, on the other hand, can prolong distress and potentially cause harm by marginalizing helpful cultural ways of coping (IASC, 2007). Rituals build the capacity for social connection and emotional self-regulation (Hobson, Schroeder, Risen, Xygalatas, & Inzlicht, 2018). Coproducing culturally appropriate interventions with community organizations that utilize rituals, creative arts connected to cultural heritage, faith-based rituals, and collective coping strategies like storytelling (e.g., Qur’anic stories about coping with trials and tribulations) is encouraged as it can support the development of culturally informed resilience (Hammad & Tribe, 2020a). Social support and religion are primary sources of resilience for people affected by collective trauma and loss (e.g., Hammad & Tribe, 2020a, 2020b; Somasundaram & Sivayokan, 2013).

In most disasters, family and community networks can be significantly disrupted; even if family and community networks remain undamaged, disaster-affected people will benefit from assistance with activating and strengthening social support networks (IASC, 2007). IASC (2007) recommends these networks be facilitated by women’s and activity groups and incorporate concrete common interest activities such as cooking. Social support helps promote wellbeing, better mental health, and community resilience, and has been found to reduce mental health problems (e.g., Fowler et al., 2003; Friedli, 2009; Tse & Liew, 2004).

Group facilitators’ background and training

The first three authors coproduced and cofacilitated the Hand of Hope therapeutic group; the fourth author provided consultation, supervision, and support. All four authors are experienced in offering culturally appropriate and faith-informed therapeutic interventions.

The first author is a Middle Eastern (Levantine) Muslim counselling psychologist and integrative psychotherapist, specializing in complex trauma, traumatic bereavement, and culturally sensitive therapy; she works at NHS GHWS (adults service) and has trained in Islamic counselling. She has conducted research on Arab mental health and how Arabs cope with ongoing collective trauma and loss and has developed culturally appropriate therapy services for Muslims.

The second author is a key community member and a Moroccan Muslim Arabic-speaking family systemic practitioner at NHS GHWS (children and young people’s service); she has trained in Islamic counselling. She specializes in the development and delivery of trauma-informed, culturally sensitive and faith-informed family, group, and youth interventions as well as community engagement.

The third author is Moroccan, Muslim and Arabic-speaking, and works as a child, adolescent and family psychodynamic psychotherapist and adult integrative counsellor at Al-Hasaniya Moroccan Women’s Centre.

The fourth author is a key community member, psychotherapist, Islamic counsellor, CNWL community collaborations service manager and NHS cultural consultant. She developed and managed the Arabic Families Service at CNWL, a service for Muslim Arabic-speaking families who would not engage in mainstream mental health services. Part of her role also involves specialist consultation, training, and supervision to the NHS, local authority and government organizations, and enhancing wellbeing as part of an integrated health approach where spirituality, faith, and culture are a core resource. Since the Grenfell tragedy she has played a key role in facilitating discussions and opportunities for organizations to develop relationships and capabilities with local communities that are necessary for moving beyond Grenfell and ensuring that the community voice is amplified at decision-making levels. She also developed the Together for Grenfell collaborations model which connects the local authority, local community organizations, and the NHS to develop and provide culturally appropriate interventions for the community that support existing ways of coping with trauma and loss. She is Muslim and of Moroccan heritage.

Community consultation and coproduction: identifying barriers and adaptations made

The process of how the Hand of Hope therapeutic group (a project of Together For Grenfell) was established and coproduced was organic. The phases involved community mapping, community consultation, establishing partnership work between services and organizations, coproduction, delivery and evaluation of the interventions. As part of outreach efforts for the Together For Grenfell project, the third author spent time over a period of a few months building relationships with community members in the local community center. This involved her taking part in community activities and informal support and discussions with community members over tea and coffee. She attended the community center twice a week. The community members were aware she was a psychotherapist. During this period there was mass displacement, therefore some people would spend time in community venues, as they were living in hotels at the time. The third author reported that the community members she was engaging with did not understand what therapy was and assumed it was for ‘crazy’ people, and that the women who had engaged in mainstream mental health services reported a lack of culturally appropriate mental health care. The other authors were also involved in community consultation and similarly received feedback from some sections of the MENA-origin Muslim community regarding the lack of culturally appropriate mental health care.

First, community consultation and partnership working between services was established, recognizing that local community organizations hold valuable knowledge and cultural expertise (e.g., Lane & Tribe, 2010). Through the Together For Grenfell project a partnership was established to work collaboratively to address the psychological needs of the MENA Muslim community who were not engaging with mental health services. We discussed the importance of offering collective interventions and restoring cultural healing practices (e.g., communal gatherings over food are central to the grieving process), as this had been disrupted in part because of the mass displacement that had taken place. We also discussed the importance of working systemically to engage families, as the women were not consenting for their children to access mental health services following the fire. This was why it was also important to have a collaboration between health services serving adults, children, and young people.

Second, during her outreach efforts described earlier, the third author approached the women who seemed most in need and wanted more structured support. The women were asked what their needs were and what type of activities they would like. They requested to focus on their religion, cooking and sharing a meal together, and connecting with other bereaved women. The intervention was introduced as the ‘Hand of Hope’ group, which involved cooking activities and a space to talk including talking about trauma and grief they have experienced. The intervention was not labelled as a mental health intervention due to the stigma and shame associated with accessing mental health care.

Third, the women were invited to the first session, where we hosted lunch for them. We introduced ourselves as therapists and where we worked, but we did not emphasize and draw attention to our professional roles. During our lunch, these women were consulted to: (1) understand what barriers/difficulties they encountered in accessing mental health services, so that we could try to address these barriers and improve access to services; and (2) establish their needs and what type of support they would like, to better inform service provision offered to them. Table 1 outlines the reported barriers and difficulties reported by the women and the adaptations made to address these. During our meal, we discussed in greater detail what activities and topics they would like to focus on in the group. The group requested to cook and share meals together, focus on their religion, access faith-informed culturally appropriate therapeutic support, and connect with other bereaved women. The group members decided what we would cook in the next session and we made a list of ingredients for the group facilitators to purchase. We created a group contract asking them what they needed for the space to feel safe and comfortable. We then started running the group weekly.

Fourth, at various intervals, we checked in with the group regarding whether the group was meeting their needs, topics to focus on, etc.

| Barriers reported in accessing mental health services | Adaptations made to the psychological group intervention to address reported barriers, promote community engagement, improve access to services and improve service provision |

|---|---|

- Shame and stigma attached to mental health and seeking therapy - Formal delivery of therapy1 |

|

| Language barriers |

|

| Mistrust of all statutory services |

|

| Lack of culturally appropriate faith-informed therapies |

|

The interventions focused on utilizing positive religious coping as a resource for clients by integrating religious scriptures to reduce distress, to enhance positive coping strategies and resilience, and to aid therapeutic concepts and strategies relating to facilitating emotional expression, the mourning process, and processing of trauma and loss.

An example of integrating religious scriptures to normalize crying/grief responses following bereavement

In this section, we discuss an example of how we integrated religious scriptures into both Hand of Hope therapeutic group interventions to normalize crying/grief and mourning responses following bereavement.

In terms of the context, some group members reported cultural beliefs conceptualized as religious prohibitions regarding expressing distress and crying following any longer than three days after a bereavement. The group members reported this was causing additional distress and impeding on their mourning process, and similar observations were made by the group facilitators. Some group members also reported experiencing distress due to negative religious coping, for example in feeling punished or abandoned by God.

The aims/goals of integrating religious scriptures were to normalize grief responses and crying following bereavement and to reduce distress connected to negative religious coping. Using religious scriptures could promote balanced thinking regarding beliefs held by some group members that loss and hardship is an indication of God’s punishment toward them and that expressing distress/crying is an indication of being discontent with God’s decree, or that it indicates low iman (religious faith). Muslims endeavor to follow Prophet Muhammad’s sunnah (behaviors and sayings in various life situations). In Islam, prophets are considered the most beloved by God and it is considered that believers including prophets are tried in proportion to their faith. These concepts were used to help address the aims/goals mentioned above.

The method utilized sayings from Hadith and Qur’anic examples from the life of the prophets to illustrate how the prophets were afflicted with trials, tribulations, hardship, multiple losses, and traumatic events. For instance, when the Prophet Muhammad’s 18-month-old son Ibrahim died, the Prophet cried. Abdur Rahman bin `Auf said, “O Allah’s Apostle, even you are weeping!” He said, “O Ibn `Auf, this is mercy.” Then he wept more and said, “The eyes are shedding tears and the heart is grieved, and we will not say except what pleases our Lord, O Ibrahim! Indeed we are grieved by your separation.” (Saheeh Al-Bukhari). This Hadith highlights how grieving and feeling sadness following bereavement is a prophetic tradition and an expression of compassion; thus reframing this as beneficial to the individual to allow for sadness and grieving (note: mercy (rahma) holds a different meaning in Islam and is akin to compassion). The Prophet Muhammad experienced multiple bereavements and was orphaned by the age of six; in adulthood, the loss of his wife Khadija and uncle within a short period is referred to as the ‘year of sorrow’. In another example, Prophet Yaqub was informed that his son Prophet Yusuf had been killed. Over an extended period of time, Prophet Yaqub grieved deeply and cried so extensively that it affected his eye sight. His intense grief is expressed in the Qur’an, “And he (Yaqub) said “Oh, my sorrow over Yusuf,” and his eyes became white from grief…” (Surah Yusuf, 12:84).

Reflections and challenges

Collaboration between services and third-sector organizations and coproduction was key to the success of the interventions. It was a challenge to build a trusting relationship because the group members had difficulty in trusting us as therapists, the community, and the other group members; we had to work really hard to build trust. For example, some service users did not want to complete basic information sheets to register their attendance. Their lack of understanding of therapy and how it works was also a challenge; they automatically brought in their own negative experiences of therapy and doubts about whether therapy would work, especially when touching on trauma and loss. We managed this by adopting a gentle and warm approach and focusing on restoring cultural healing practices and social connectedness. We showed respect to their values and beliefs and this appeared to help encourage them to trust us. Abi-Hashem (2014) highlights how many MENA-origin people expect the therapeutic exchange to be warm and friendly and would not respond well to mechanical, formal, business-like relationships. Mental health professionals adopting a formal expert position that accentuates the power imbalance is likely to impede access to and engagement in therapy for this client group (Hammad & Hamid, in press).

During the initial stages of the group, some group members had difficulties and arguments with each other which required us to offer mediation. Conflict between group members is a common feature of the group process known as the storming phase (Tuckman, 1965). Other challenges included the time needed to build relationships between services and the community and working in a setting with high levels of media and political scrutiny. There were challenges to working informally, which primarily related to time-keeping and ensuring people did not talk over each other. We managed this by revisiting the group contract. Some of the group facilitators also experienced the tension between their therapy training advocating a neutral stance and nondisclosure on the therapist’s part, and our cultural awareness that we needed to make non-significant disclosures to help reduce the power imbalance, strengthen the therapeutic alliance, and to create a warm environment. Hamid, Scior, and Williams (2020) found that mental health professionals reported finding it helpful to make disclosures to reduce perceived power imbalances with refugee Syrians.

Similarities and differences between the two Hand of Hope therapeutic group interventions

We coproduced and carried out two separate service evaluations of the Hand of Hope therapeutic group interventions with two different groups of women. The service evaluations followed the same procedures. Both interventions focused on engaging bereaved MENA Muslim women affected by the Grenfell Tower fire by coproducing a culturally appropriate faith-informed therapeutic group intervention. Both groups consisted of women who had lost multiple close friends in the fire. We used the same approach, adaptations, and framework in both interventions. The differences pertain to the time period, different presenting problems the women were experiencing, and cultural healing practices. The primary aim of the first group intervention was to improve access to mental health services and to support stabilization. The second group intervention primarily focused on promoting wellbeing and resilience.

The first Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention ran 10 months after the Grenfell Tower fire in 2018 with first- and second-generation MENA-origin Muslim women. The following issues were identified for this group of women: shame and stigma associated with mental health and accessing mental health care, mistrust of all statutory services, presentation of symptoms consistent with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and traumatic bereavement, difficulties in mourning/grieving, non-engagement with mental health services on an individual and family level, lack of mental health awareness, and disruption to social support networks and Islamic and MENA customs following bereavement and collective trauma and loss. The group sessions were focused on restoring these customs and the following cultural healing practices: group cooking, communal gatherings over food, and oral storytelling—‘hikaya’.

The second Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention ran 22 months after the Grenfell Tower fire in 2019 with first-generation MENA-origin Muslim women, all of whom reported having no family in the UK. All group members had accessed individual therapy in connection to the Grenfell Tower fire. The following presenting problems were identified: low mood, social isolation, and the women reported not engaging in life like they did prior to the fire. The group sessions focused on the following cultural healing practices: communal gatherings over food, oral storytelling of seerah and Qur’anic stories of the prophets, and group nasheed singing and traditional drumming (Muslim women’s choir).

In the next section, we outline the first Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention and the service evaluation for this group intervention.

Service Evaluation One

Method

Community consultation

The first Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention was coproduced with a group of 10 British Arabic-speaking, MENA-origin, Muslim first- and second-generation women, affected by the Grenfell Tower fire. All reported witnessing the fire. Eight women were bereaved and had lost multiple close friends in the fire; six women described symptoms consistent with PTSD, and three women were permanently displaced in connection with the Grenfell Tower fire. Prior to establishing the group, only two women were accessing therapy via NHS GHWS, but none of the group members’ children nor the other eight women were engaging with mental health services or accessing therapy. For the first Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention, the group requested to connect with other bereaved women, cook and share a meal together, focus on their religion, and access faith-informed culturally appropriate therapeutic support. Some of the women knew each other from the community.

The Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention consisted of eight once-weekly two-hour sessions and ran from April to June 2018, 10 months after the Grenfell Tower fire. The aim was engagement, to provide culturally appropriate faith-informed therapeutic support, reduce the shame and stigma attached to mental health and therapy, provide psychoeducation, strengthen and activate social support networks, support stabilization, and improve access to services for the service users and their children. The group sessions focused on the cultural healing practices/collective cultural coping strategies: group cooking and communal gatherings over food (Abi-Hashem, 2006; Zarifi, 2015), and ‘hikaya’ oral storytelling (Atallah, 2017; see Table 2.).

| Cultural healing practice (content and method): | Hospitality, cooking a meal together and communal gatherings over food |

|---|---|

| Context: | Some of the group members had been living in hotels as they were displaced from their homes following the fire. The hotels did not always have kitchen facilities to be able to cook a meal. |

| Goal/aims: | To honor important customs following bereavement; facilitate expression; promote grounding, stabilization, and social connectedness; re-engage participants in activities that they used to enjoy. |

| Concept: |

|

| Method: | Cooking and sharing a meal as a group We provided food (e.g., traditional biscuits and bread, olives, fruit, meze appetizers, etc) and mint tea. As per MENA cultural customs, we served the group members because we invited them and the host serves its guests. The group decided together what they would like to cook for the next session and as a group we wrote out a shopping list of ingredients and amounts, which we (facilitators) purchased. The main dish that the group members and facilitators made together was typically intricate traditional Arabic pastries. Some group members chose to bring in dishes to share with the group. By restoring culturally familiar ways of coping with trauma and loss, we observed that when gathering as a group and cooking a meal together, the group members were processing their traumatic experiences and loss collectively, as they normally do culturally; it was natural, non-threatening and at their own pace. This appeared to help them to feel at ease and fostered bonding between the group members and the facilitators, and strengthened some of their interpersonal relationships. The group members also collectively mourned and remembered the deceased. The processing of traumatic material and loss was done informally whilst cooking and eating together because a) cooking stimulates the five senses (Josephy 1994) and utilizing the five senses is the main way to help ground traumatized individuals so that they do not dissociate; b) the use of physical movement can facilitate trauma processing as it sends a non-verbal message that the trauma is over (Rothschild, 2003) and can also help to create dual awareness so that the client remains fully present during trauma recall; and c) cooking taxes the working memory (Wang et al., 2011). There is evidence to suggest that engaging in tasks that tax the working memory reduces the vividness and emotional intensity of disturbing memories (Engelhard et al., 2010). Cooking is considered a creative art; the use of creative materials has a soothing effect that decreases stress reactions and aids expression (Malchiodi, 2014). |

| Cultural healing practice (content and method): | Oral storytelling—‘hikaya’ |

| Goals/aims: | Facilitate expression and mourning process; normalize grief responses; utilize faith to promote balanced thinking, positive coping, resilience and self-compassion; promote social connectedness. |

| Concept | In MENA cultures, oral storytelling is a culturally appropriate collective strategy used to cope with collective trauma and loss (Atallah, 2007; Zarifi, 2015). The life story (seerah) of the Prophet Muhammad and Qur’anic stories of the prophets are recognized as a helpful pathway to model and cultivate resilience (e.g., Hammad & Tribe, 2020a; Marie, Hannigan, & Jones, 2017). Muslims endeavor to follow Prophet Muhammad’s sunnah (behaviors and sayings in various life situations) which encourages followers to survive or thrive in challenging and adverse conditions (Ramadan, 2007). |

| Method: | Oral storytelling delivered informally in conversation; group members sharing their life stories and experiences of the Grenfell fire tragedy; Qur’anic stories about coping with calamities, trauma, and grief were woven into the conversation by the facilitators and the group members. |

Outline of the Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention one

In this section, we outline the first Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention. “Engagement and Consultation,” the first two sessions, focused on establishing relationships and a group contract, building trust by exploring the religious concept of amanah (trust), facilitating group bonding and engagement via group activities and icebreakers, identifying the group’s needs and coproduction. To manage interpersonal difficulties mediation was offered to group members who had historic personal difficulties with each other.

Session 3, “Coping with Loss”, involved exploring ways of coping with loss informed by their faith and supporting bereaved friends and family, exploring their views on bereavement, loss/grief-related emotions, and the impact of suppressing emotions. The aim was to provide psychoeducation on bereavement and strengthen positive coping.

Session 4, “Managing and Making Sense of Traumatic Experiences/Responses,” focused on supporting clients to recognize and manage trauma responses/symptoms by providing psychoeducation on trauma responses, reducing shame and stigma by normalizing trauma responses, promoting stabilization by exploring self-soothing techniques, and trauma and anxiety symptom management, including faith-informed grounding techniques like listening to Qur’an and dhikr (remembrance of God).

Session 5, “Exploring Impact of Bereavement and Grief,” focused on exploring their perspectives on grieving/mourning including Islamic perspectives, psychoeducation on grief/bereavement responses to increase awareness of the impact of bereavement and reduce shame and stigma, and remembering their loved ones and sharing memories of them. To support the processing of loss and distress, we normalized grief responses and permissibility to cry using Qur’anic stories of the prophets to promote balanced thinking regarding negative religious coping and support cognitive processing regarding beliefs about crying and expressing distress. We reflected on the religious concept of sabr (perseverance) and Qur’anic verses and Hadith group members found meaningful to aid positive coping.

Session 6, “Exploring Experiences of the Grenfell Fire Tragedy,” involved exploring the emotional impact of their trauma and loss and processing trauma in a culturally familiar way. Some group members chose to narrate their experiences of the fire in sequential order and were supported by the group. We explored religious forms of coping and religious conceptualizations of their experience.

Session 7, “Talking about Loss with Others and Mental Health Awareness,” explored what mental health and therapy is and associations made to increase mental health awareness and challenge stigma associated with mental health and seeking therapy. In this session, we explored the group ending, remembered the deceased, and normalized difficult feeling states. We also addressed their concerns that they would be burdening their friends if they opened up about their difficulties, by modelling difficult conversations, promoting social support, and exploring how group members would like to be supported by others.

Session 8, “Group Ending/Marking Eid,” involved exploring experiences of Eid without their loved ones, reflecting on the group’s journey, and supporting their request to mark their first Eid al-Fitr since the fire as a group.

Participants

All 10 group members were verbally invited to take part in the service evaluation. Seven participants that took part in the service evaluation were British first- and second-generation MENA-origin Muslim bereaved women, ages ranging 36 to 83, affected by the Grenfell Tower fire. Three group members who were unable to take part in the focus group interview due to other commitments were contacted individually to provide verbal feedback as part of the service evaluation; their feedback is included.

Procedure

Prior to the service evaluation, NHS approval was obtained. All participants were verbally provided with a description of what the service evaluation involved, the purpose, and the voluntary nature of their participation. Verbal consent was gained by the participants before taking part in the service evaluation. Participants were aware that they could withdraw from the evaluation, refrain from answering any questions, that the data would be anonymized with no identifying details, and that their participation would not negatively affect current or future services offered.

A mixed-methods service evaluation of the Hand of Hope intervention was conducted by the first three authors. A semi-structured focus group was held in June 2018 with seven group members in Arabic and English, which included the group members anonymously rating quantitative questions on a Likert scale. The focus group was audio-recorded with the participants’ consent and transcribed verbatim in English. Examples of focus group questions included: “how have you found the group?” and “how did you find the cooking activities?” The questionnaire was read aloud and participants completed a paper copy anonymously, which was deposited in a box. The audio recording of the focus group was translated by the third author, and transcribed verbatim in English by the first author. The data regarding referrals and access to therapy/services before and after the group was monitored, overseen, and collected by the first three authors and checked on each service’s databases; participants were also individually asked if they were accessing any services/therapy prior to inclusion in the group.

Data analysis

A thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) guidelines was conducted on the English translation of the focus group interview by the first author and was cross-referenced by the second author. The transcript was analytically coded on a line by line basis to generate initial codes and to identify possible themes. There was an emphasis on identifying distinct themes which related to the barriers reported in accessing therapy/mental health services, service user experience of the intervention, and evaluating the impact and outcomes of the intervention. The potential themes were reviewed to ensure that it captured the data contained in the transcript, and some subthemes were collapsed and renamed to better represent the data. Data extracts are provided in the findings section to allow the reader to evaluate whether the theme is representative of the data. The anonymized quantitative ratings were averaged using a calculator.

Findings and Discussion (Service Evaluation One)

Barriers to accessing mental health services and therapy

The findings regarding the theme of barriers to accessing mental health services and therapy will be discussed first, followed by the (theme) outcomes of the first Hand of Hope group evaluation. To avoid repetition, the data extracts on the barriers presented are in response to the question, “Have you encountered any difficulties or barriers to accessing therapy in relation to Grenfell?”.

Shame and stigma attached to mental health and seeking therapy

Consistent with the literature, all reported that the shame and stigma attached to mental health and seeking therapy was a major barrier to accessing mental health services (e.g., Alhomaizi et al., 2017; Arday, 2018; Hamid & Furnham, 2013; Memon et al., 2016; Rayan & Jaradat, 2016; Woods-Giscombe et al., 2016). Some participants reported fears of being ostracized if they accessed support. All referred to mental health as meaning someone is “mad,” and some expressed that therapy is for “crazy” or “psycho” people. It is possible that their understanding of mental health and mental health care is informed by their experiences in their countries of origin. Mental health typically has negative connotations and is popularly associated with people experiencing severe mental illness (e.g., Amri & Bemak, 2013) such as psychosis or people with a forensic history; mass media often depict people with mental health problems as dangerous and unpredictable (e.g., Overton & Medina, 2008). Mental health support in the MENA region is also often associated with being locked up in an asylum (e.g., Amri & Bemak, 2013; Youssef & Deane, 2006). Asylums were introduced during periods of British and French colonialization and lacked standards of psychiatric care (Fernando, 2014). Research in Egypt indicated that mental illness can be perceived as a threat to social order, which is managed by the segregation and physical isolation of psychiatric facilities (Coker, 2005). Some comments made by group participants follow.

“I wouldn’t go and ask for help…I feel embarrassed and ashamed to ask for help.”

“I feel quite shy to ask for support, I worry I would be left out by other people if I seek support.”

Language barriers

All Arabic-speaking participants reported language as a major barrier and stated their need to express themselves in Arabic and that they could not express themselves emotionally or fully in English (Abu-Ras, 2003; Arday, 2018; Memon et al., 2016; Mind, 2013a; Youssef & Deane, 2006). They expressed feeling uncomfortable having therapy in English or via interpreters:

“The difficulty is the language. I can’t express my real feelings in English…I can express it in Arabic.”

“…[Before Grenfell] for each session I had a different translator and it didn’t work…it was the language, even if it was Arabic they spoke a different dialect...”

Delivering therapy in a formal manner makes them feel like “a sick person”

All reported that they would reject help if therapy was delivered in a formal manner where they felt like “a sick person.” They appeared to feel like “a sick person” if the helping professional related to them from a position of formality which drew attention to their professional role. It appears that they experience the professional “doctor”—client “sick person” dynamic disempowering, and therefore they opt not to seek therapy. Memon and colleagues (2016) and Arday (2018) found that ethnic minority clients in the UK experienced the relationship between the healthcare provider and service user as centered on power and hierarchy, which created barriers for them to accessing mental health services. Hassan and colleagues (2016) found that many Syrian clients found the expert position of the mental health professional disempowering. Participants describe below their need for mental health care to be delivered informally and in a way which is sensitive to the power dynamics.

“These therapists even though they are strangers to us, they need to be approachable, comfortable, acceptable…”

Interviewer: What are the things you would want the therapists to do to make it feel more acceptable?

“…informal [group agrees], they don’t make you feel like you are a sick person. I would prefer that the therapist is not formal, and they are not in a position where they are the professional, and we are like a sick person. I want it to be like it’s a person I met at the park and I like her and even if I don’t know her, I talk to her.”

Mistrust

A major barrier reported was their lack of trust, which may reflect their negative perceptions of mental health services (Arday, 2018; Keating & Robertson, 2004; Youssef & Deane, 2006), or confidentiality concerns (Youssef & Deane, 2006). Many people from the MENA region come from countries with punitive and oppressive governments that routinely conduct surveillance. Furthermore, Mind (2013 cited in Arday, 2018) highlights how ethnic minorities in the UK increasingly encounter surveillance in public spaces. Younis and Jadhav (2019) highlight how Muslims also encounter surveillance in public spaces in the UK including healthcare settings which may impede access to health care. The women also expressed a mistrust in all statutory services including the NHS following the fire, with difficulties discerning between services and providers, which may also explain these findings.

“I don’t trust anyone. I’ve never done therapy to know.”

“We need to trust the therapists that come to talk to us…we feel like we can’t trust them.”

Perceiving/experiencing therapists as not understanding their culture and religion

All referenced the importance of having therapists who understood their religion and culture and requested their religion to be incorporated into psychological interventions (e.g., Bagasra & Mackinem, 2014; Gilbert & Parkes, 2011; Yamada et al., 2019). Consistent with the literature, participants reported a lack of culturally appropriate mental health services (Arday, 2018; Grey et al., 2013; Mind, 2013a; Mental Health Foundation, 2018; Woods-Giscombe et al., 2016). Some expressed the interventions on offer by mainstream mental health services and therapists in general as lacking an understanding of their culture and religion, therefore they did not consider therapy as relevant or relatable to them.

“When I got referred the first time, the therapist was not Moroccan; I didn’t feel like I could relate to her and like she could understand my culture.”

“The therapist needs to understand and include my religion otherwise I wouldn’t be able to relate.”

Outcomes and the impact of the Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention one

Outcome 1: Improved community engagement and stigma reduction

Participants reported wanting psychological support that they could relate to otherwise they would have disengaged. By incorporating their language, faith, and culture into the intervention, all participants reported experiencing the intervention as relevant and relatable. Participants expressed that having therapists who were familiar with their culture and religion helped them to engage.

“I like coming here; it’s nice to speak with therapists. I feel like you get me, I don’t have to explain my culture and religion to you.”

“…I can see that you understand the religion so I can relate.”

“I don’t think I would have stuck at it this long otherwise if there was no focus on religion.”

Participants expressed the relief they experienced in being able to express themselves in their mother tongue.

“I’m comfortable expressing myself in my language, it brings me relief.”

Participants were unanimous in wanting therapy delivered informally. Some appeared to hold preconceived negative ideas about therapy. All expressed that an informal therapeutic approach helped them to feel comfortable because therapy was being delivered without them feeling like they were receiving therapy; an informal approach may have addressed the stigma and shame attached to mental health and accessing therapy. This suggests that the Hand of Hope, an informal culturally appropriate faith-informed therapeutic intervention may be acceptable to communities who are not amenable to therapy in the traditional format that is delivered within mainstream mental health services. The use of food and the group facilitators cooking and eating with the group appeared to help add to the informal set up of the group.

“It hasn’t felt formal [group agrees]…that’s what makes it good, it doesn’t feel like therapy; it feels like you are sitting amongst people, it’s a nice relaxing environment, normally therapy is like…[two group members]: it feels like a family gathering; this experience has changed my mind about therapy…[Group member]: it’s not like you are the doctor and we are the patient, it’s relaxed; it’s the relationship you created with us.” [Group agrees.]

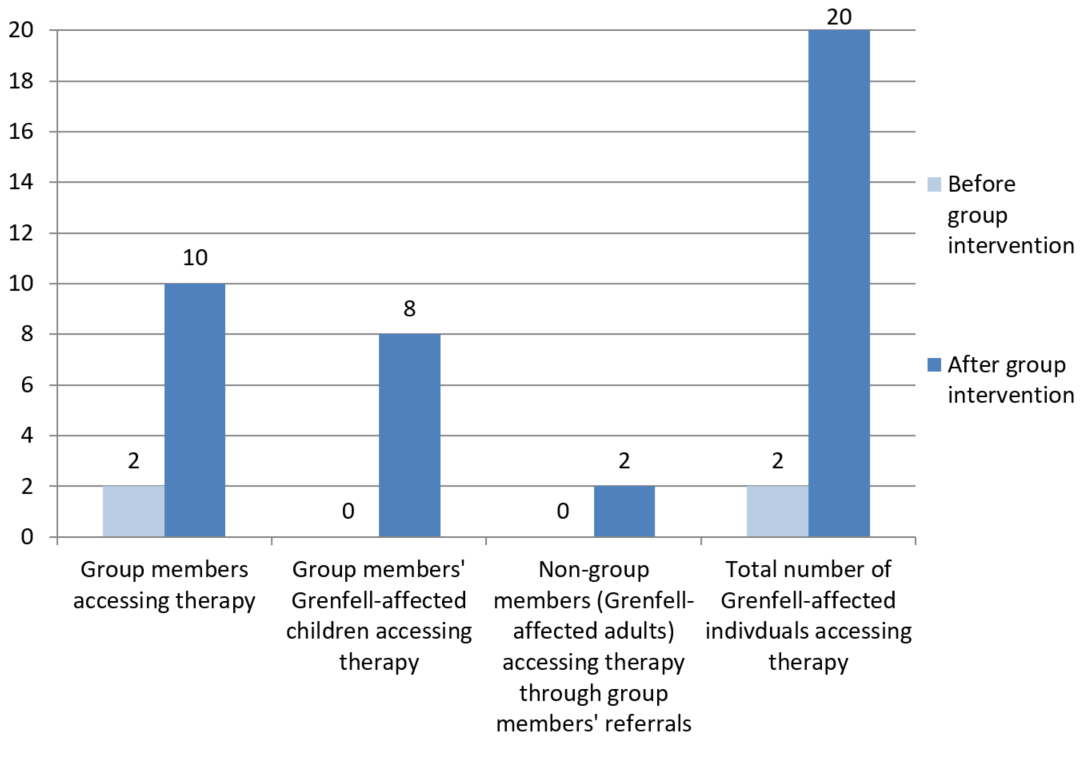

Based on anonymized feedback, 86% reported that taking part in the group helped them to be more open to having individual therapy should they need it (57% strongly agreed, 29% agreed and 14% were neutral). We also accessed additional MENA-origin Muslim individuals who did not attend the group, perhaps due to the changed attitudes of the group members. This included eight of their bereaved children and two of their adult family members/friends who accessed therapy. Prior to the intervention, only two individuals were accessing individual therapy via the NHS GHWS. After the intervention, 20 individuals accessed therapy with a 100 percent retention rate for all; five of the most affected group members accessed individual therapy (see Figure 1). The qualitative feedback reported improved attitudes toward therapy, and the number of individuals accessing therapy would suggest that the intervention helped challenge the shame and stigma attached to mental health and seeking therapy and improved access to mental health services. It also highlights the benefits of coproduction and culturally adapting interventions to improve access to services, service experience, and engagement and retention of ethnic minority and faith groups (e.g., Mir et al., 2013, 2015, 2019; Nagel, Robinson, Condon, & Trauer, 2009; Perry et al., 2019; Soto et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2018).

Outcome 2: Fostering of safety, stabilization, building of trust, greater mental health awareness, and improved emotional regulation

Based on anonymous ratings, 72 percent of participants reported feeling more able to manage any difficult or unpleasant feelings since taking part in the group (the remaining rated neutral); this would suggest that the group intervention supported stabilization and improved emotional regulation. Based on anonymous ratings, 86 percent reported gaining a better understanding of grief and trauma and how it affects them since taking part in the group (the remaining rated neutral).

Most reported finding the group “atmosphere relaxing”. They reported feeling more “relaxed” and “relieved” since taking part in the group and using the space to explore their difficulties.

Interviewer: How have you found the group?

“I feel relieved since attending this group. I feel more able to talk, whereas before I would hold it in. I felt connected to you guys so I could open up.”

“It helped me because it gives me peace of mind.”

“I feel relieved and more relaxed, like I have a family.”

Participants reported trusting the therapeutic space created, addressing the barrier of mistrust discussed earlier.

“…It’s a place to relax and know your word is not going to go out. It’s the trust. You feel safe…I know if I have a problem I will get help.”

“I did trust the group, if I didn’t I wouldn’t come; not everyone is like this and it changed my perspective on people.”

Outcome 3: Benefits of cooking activities on wellbeing

All reported that the group cooking activities helped improve their wellbeing, as noted by Farmer and colleagues (2018) and IASC (2007). Participants reported finding the cooking activities enjoyable, therapeutic, and relaxing, with many likening it to being at home with their family; it helped facilitate bonding, creativity, expression, and a sense of accomplishment.

“We like cooking, cooking is creativity. Cooking brings me relief, I find cooking relaxing and therapeutic. You are creating something, you see the results. I feel happy that we created something together… [Group member:] We relax, it’s like a family [group agrees], it’s happiness.”

“I’m using my creativity [cooking] to express myself.”

“Cooking is team building, it’s socializing.”

Outcome 4: Strengthening of social support networks and reduced social isolation

All reported that taking part in the group reduced their social isolation and loneliness and increased communication with other group members outside of the sessions.

“I didn’t like the fact that I was on my own. I’m no longer isolated, I’ve made friends.”

“…I feel more connected, I got to know people better…I feel bonded with them.”

Most referenced experiencing the group as like “family.” Perhaps the strengthening of their relationships was supported by the facilitation of culturally familiar coping strategies—communal gatherings over food.

“I feel like I have a new family like in my old country, we gather together and eat.”

In the next section we outline the second Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention and the service evaluation for this group intervention.

Service Evaluation Two

Method

Community consultation

A second Hand of Hope group intervention was coproduced with a different group of women, as part of the Together For Grenfell project. For the second Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention, the group requested to focus on their religion, the seerah, stories of the prophets, and to engage in traditional arts. The group comprised of six Arabic-speaking MENA-origin Muslim bereaved women, affected by the Grenfell Tower fire tragedy, who had witnessed the fire, had historic or current trauma symptoms in connection to the Grenfell Tower fire (based on assessments from individual therapy or contact with services), and had lost multiple close friends in the fire. All reported having no family in the UK. Most of the women were known to NHS GHWS and Al-Hasaniya Moroccan Women’s Centre through previous outreach efforts, or previously accessing individual therapy, and were invited to join the group; some women joined through word of mouth via the group members. We held a lunch and invited the group of six women to identify the group’s needs and discuss coproducing a group intervention.

The women reported being low in mood, not engaging in life like they did prior to the fire, and feeling socially isolated. The intervention involved nine weekly 90-minute sessions and ran from April to June 2019, 22 months after the Grenfell Tower fire. The second coproduced Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention was run in partnership with NHS GHWS (adults service) and a third sector organization Al-Hasaniya Moroccan Women’s Centre. The group was coproduced and co-facilitated by the first and third author. The group sessions were focused on the following cultural healing practices: communal gatherings over food, seerah oral storytelling and Qur’anic stories of the prophets, and group nasheed singing and traditional drumming (Muslim women’s choir; see Table 3.). The adaptations outlined in Table 1 were applied with this group. The aim of the intervention was to strengthen resilience, promote behavioral activation, and improve wellbeing, mood, positive coping, and social support.

| Cultural healing practice (content and method): | Hospitality and communal gatherings over food |

|---|---|

| Goal/aims: | To facilitate expression and social connectedness; re-engage participants in activities that they used to enjoy. |

| Concept |

|

| Method | Sharing a meal together. We asked the group what type of food they would like. The group facilitators provided and served traditional MENA food and mint tea to the group members. The group facilitators hosted the group, therefore we served the group members as per MENA cultural customs. Some group members also chose to bring in dishes to share. |

| Cultural healing practice (content and method): | Oral storytelling—‘hikaya’ |

| Goals/aims: | Facilitate expression; normalize grief responses; utilize faith to promote balanced thinking, positive coping, resilience and self-compassion; promote social connectedness. |

| Concept | In MENA cultures, oral storytelling is a culturally appropriate collective strategy used to cope with collective trauma and loss (Atallah, 2007; Zarifi, 2015). The life story (seerah) of the Prophet Muhammad and Qur’anic stories of the prophets is recognized as a helpful pathway to cultivate and model resilience (e.g., Hammad & Tribe, 2020a; Marie, Hannigan, & Jones, 2017). Muslims endeavor to follow Prophet Muhammad’s example in various life situations which encourages followers to survive or thrive in challenging and adverse conditions (Ramadan, 2007). |

| Method | The lives of Prophet Muhammad and Prophet Yusuf were discussed in chronological order, with psychological reflections. The prophetic stories related to themes of coping with calamities, trials and tribulations, multiple traumas, and losses/bereavements. |

| Cultural healing practice (content and method): | Collective nasheed singing and traditional drumming |

| Aims/goals: | Connect with faith resources; promote social connectedness and psychological wellbeing, improve mood, engage in enjoyable activities; behavioral activation. |

| Concept: | There are traditions in Islamic history of integrating music in the spiritual care and alleviation of mental health problems and psychological distress (Isgandarova, 2015). In this context, music refers to the use of nasheeds with traditional musical instruments (e.g., darbuka drums), which can be used as a ritual for psychological and spiritual wellbeing, particularly in the Sufi traditions. Islamic spiritual songs are included in the category of nasheed (in Arabic) and may help people to find meaning in their suffering, connect with God (Isgandarova, 2015), and can be a form of dhikr (remembrance of God). |

| Method | Collective nasheed singing and traditional drumming using darbuka drums. The group were invited to select nasheeds they would like to sing. As a group we reflected on the meaning of the nasheeds we sung. Group members who were experienced in playing the darbuka drums taught the group drumming skills and techniques. The group facilitators participated in the nasheed singing and drumming with the group. |

Outline of Hand of Hope therapeutic group intervention two

The first two session carried the theme of “Engagement and Consultation” and focused on building trust by exploring the religious concept of amanah (trust), establishing relationships and a group contract, facilitating group bonding and engagement via group activities and icebreakers, identifying the group’s needs and coproduction.

Session 3, “Sources of Resilience and Self-Soothing,” explored their interests, ways they manage stress and self-soothe (including faith-informed grounding techniques), nightmare and anxiety management, and religious resources that promote self-regulation and resilience. The aim was to promote stabilization, self-soothing, social connectedness, symptom management, and positive coping.

The fourth and fifth sessions emphasized the seerah, the life of Prophet Muhammad and his experiences of multiple traumatic events: exile, oppression, poverty, hardship, losing his parents as a child, death of his companions and children, and the ‘year of sorrow’ deaths of his wife and uncle. We explored his grief and trauma responses and expressions of sadness and distress. The aim was to promote positive forms of coping and resilience, reduce distress, normalize expressing distress, sadness and grief responses, and promote balanced thinking pertaining to negative religious coping and appraisals. These aims were extended to the following session content.

Sessions 6 and 7 exploring the life of Prophet Yusuf, focusing on his experiences of family betrayal, envy, injustice, oppression, exile, being subject to human trafficking and enslaved, and reuniting with his father. We also explored Prophet Yaqub’s grief response to hearing the news of his son’s death.

Session 8 provided an overview and psychological reflections on the stories of the prophets, with an emphasis on personal and psychological reflections on the stories of the prophets that were explored in previous sessions. We explored how the group felt about ending.

Session 9, “Group Ending/Marking Eid,” explored participants’ experiences of Eid without their loved ones and reflected on the group’s journey. The aim was to promote awareness and social connectedness.

Participants

All six group members were verbally invited to take part in the service evaluation. The five group members that took part in the service evaluation were British Arabic-speaking first-generation MENA-origin bereaved Muslim women, ages 41 to 84 years old, who were affected by the Grenfell Tower fire and had lost multiple close friends in the fire. Some of the participants experienced permanent displacement following the fire. One participant was unable to take part in the focus group interview due to other commitments. She was contacted individually to provide verbal feedback as part of the service evaluation; her feedback is included.

Methodology

The same methodology was applied as in service evaluation one (please see procedure and data analysis sections outlined in service evaluation one). A semi-structured focus group was held by the first and third authors in June 2019 with five group members, in both Arabic and English, which included the group members anonymously rating quantitative questions on a Likert scale.

Results and Discussion (Service Evaluation Two)

Outcome 1: Improved psychological wellbeing, mood, healing, emotional expression and emotional regulation