An Exploration of the Help-Seeking Behaviors of Arab-Muslims in the US: A Socio-ecological Approach

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

While evidence has shown that professional mental health services are highly effective with treatment and symptom management, not all who need those services utilize them. Furthermore, there is evidence that certain racial, ethnic, cultural, and religious groups are less likely to seek or access mental health care. The Arab Muslim minority living in the US have low rates of seeking mental health services compared to other populations. An exploratory, qualitative study was conducted to understand the help-seeking behaviors of the Arab Muslim minority in the greater Boston area. This study was conducted in order better understand help-seeking behaviors of Arab Muslims in the United States; to understand the perception they hold about mental illness, its causes, and its treatments; and to identify some of the potential hindrances and facilitators of seeking formal mental health treatment. Seventeen individual face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted with Arab Muslim laypersons, mental health professionals, and imams living in the US. Utilizing a socio-ecological approach, the study results identified factors, such as stigma and social support, that influenced help-seeking behaviors of Muslim individuals at multiple levels including the individual, interpersonal, and community level, as well as the larger environment. In addition, the study identified factors, such as information and societal norms, that cut across these levels, and help us to understand help-seeking behaviors and patterns.

Keywords: Muslim, help-seeking, access to care, stigma

Background

While evidence has shown that professional mental health services are highly effective with treatment and symptom management, not all who need those services utilize them. Mental health service utilization is defined as talking to or seeking help from a health professional about an emotional, nervous, drug, or alcohol problem within the last six months (Cooper-Patrick et al., 1999). According to the 2016 State of Mental Health in America report, 57.2% of adults with a mental illness receive no treatment. This may be due to both help-seeking behavior as well as access to care. There is evidence that some minority racial, ethnic, cultural and religious groups delay or fail to seek mental health care compared to their white counterparts (Sussman, Robins, & Earls, 1987; Zhang, Snowden, & Sue, 1998). Moreover, help-seeking behavior is not seen proportionally among different ethnicities, cultures, or religions in the US (Koenig, 1998; Lin, Tardiff, Donetz, & Goresky, 1978).

Unfortunately, research with the Arab Muslim population in the US is minimal and they are often not included in studies of minority help-seeking and access to services. In 2009, Aloud and Rathur reported that among 281 Arab-Muslim participants, only 9.6% had visited a mental health specialist in the past three years. This is significantly less than other minorities in the US (McGuire & Miranda, 2008) and than the general American population (Pescosolido & Boyer, 1999). Studies have found that 37.6% of white adults who need mental health or substance abuse treatment received care, compared to 22.4% of Latinos and 25% of African Americans (Wells, Klap, & Koike 2001). There are several factors that may play a role in this pattern of underutilization by Arab Muslims.

Mental health care utilization can be better understood by exploring help-seeking behavior. Researchers have found that the beliefs, perceptions, and attitudes toward mental illness and mental health treatment may affect help-seeking behavior. Several studies have documented that most minorities in the US, including African Americans (Alvidrez, 1999), Latinos (Alvidrez, 1999), Asian Americans (Kim & Omizo, 2003), and American Indians (Beals et al., 2005), have negative attitudes toward mental health care services; this likely results in decreased help-seeking behavior. Among some Arab Muslims, it is common to attribute the symptoms of a mental illness to either religious and/or supernatural causes. The religious causes of mental illnesses may include the belief that a mental illness is a test from God, a punishment for one’s sins, the result of a person’s weakness of faith, or God’s will and that only His Will will cure it (Weatherhead & Daiches, 2010; Youssef & Deane, 2006). Other common beliefs include the idea that mental illness is the result of possession by spirits (Jinn), witchcraft or black magic, satanic powers, or the evil eye (Aloud & Rathur, 2009; Weatherhead & Daiches, 2010; Youssef & Deane, 2006). The religious or supernatural beliefs are likely to increase the chances that people will seek mental health care from religious healers and thus underutilize formal mental health care.

Stigmatizing beliefs and attitudes about the nature of mental illnesses and mental health services may also affect whether Arab Muslims will seek formal mental health treatment. Social stigma, sometimes called public stigma, is when society, the public, or large social groups endorse the stigma of mental illness and its stereotypes, and may even discriminate based on these negative attitudes (Watson & Corrigan, 2001). This stigma usually impacts both the patient and his/her family in a process known as associative stigma (Watson & Corrigan, 2001). The experience of stigma in the Arab-Muslim community is usually characterized by isolation, embarrassment, and a strong element of denial to preserve the family’s reputation (Youssef & Deane, 2006). These attitudes have been shown to stand as barriers to help-seeking behavior in the Arab-Muslim community (Aloud & Rathur, 2009).

The underutilization of formal mental health services may also be attributed to the help-seeking preferences of the Arab-Muslim community. Aloud (2004) found a positive relationship between help-seeking preferences and help-seeking attitudes. Given that some Arab Muslims think that there are either religious or supernatural causes of mental illness, their initial help-seeking may be with an imam (Youssef & Deane, 2006); imams are religious leaders whose roles typically involves leading prayers in the mosque, providing religious advisory opinions, and offering spiritual guidance. Arab Muslims may prefer imams due to the privacy and decreased stigma associated with visiting a religious leader compared to a mental health facility (Weatherhead & Daiches, 2010; Youssef & Deane, 2006). It is not clear what percentage of Muslims seek mental health assistance from clergy, but a national epidemiological study found that roughly 25% of those who ever sought treatment for mental disorders did so from ministers, priests, and rabbis (Wang, Berglund, & Kessler, 2003).

Religious beliefs and practices also influence preferences for treatment and healing; Arab Muslims might prefer religious habits such as prayer or fasting, reading the Qur’an or hadith, or performing ritual ablutions known as wudu (which they believe has both physical and spiritual cleansing properties). Arab Muslims who believe in supernatural causes may prefer a folk healing treatment known as ruqyah. Ruqyah is the recitation of specific Qur’anic verses in an attempt to cure Jinn possession, black magic, or the evil eye and is usually performed by an imam or a religious healer (raki). Arab Muslims who have greater preferences for these resources demonstrate less favorable attitudes toward seeking formal mental health and psychological services (Weatherhead & Daiches, 2010; Youssef & Deane, 2006).

Though many studies conducted with Arab-Muslim minorities in developed countries have suggested that attitudes and help-seeking preferences typical in this community play a role in help-seeking behavior (Weatherhead & Daiches, 2010; Youssef & Deane, 2006), little research has been conducted with this minority population in the US. In addition, few of these efforts have examined factors across multiple levels, which may impact attitudes and help-seeking. A socio-ecological approach allows for a more robust exploration of how the factors influence and interact with other components to affect whether a person will seek formal mental health care or utilize other options. This project draws up upon a socio-ecological framework to understand the attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions that Arab Muslims living in the greater Boston area have about mental health and mental health treatment in order to better understand the barriers and facilitators to help-seeking within this community.

Method

In this exploratory study, semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with Muslim laypersons and key informants in the Muslim community, a total of 17 face-to-face interviews were completed. Layperson participants were recruited between February 2013 and April 2013 through fliers and study sign-up sheets that were posted at the Muslim Cultural Center in Boston, MA, emails sent via the center’s list, and announcements made during community events at the center. The study was described to potential participants as an investigation into community opinions about mental health and how they deal with daily stressors and life problems. Key informants were recruited from March 2013 to April 2013 by means of the snowball or chain referral method, as recommended by Biernacki and Waldorf (1981); this leads to study samples comprised of referrals made among people who possessed certain shared characteristics that are of research interest with others. The snowball procedure started with the interviewer’s nomination of three key informants, two Muslim mental health providers and one imam; these key informants were then asked to nominate additional key informants. All interested laypersons and nominated key informants were followed up for eligibility screening by telephone to determine if they could take part in the study.

The Northeastern University Committee on Human Subject Research Protection (IRB# 12-12-34) approved all study procedures related to recruitment and data collection. The Teachers College, Columbia University Institutional Review Board (IRB# 15-025) approved all data analysis conducted beginning October 7, 2014.

The interview guides were developed by the principal investigator and a co-author, and were informed by extensive literature reviews of similar study designs with this population. The principal investigator, who is fluent in English and Arabic, served as the interviewer in the study and conducted all 17 interviews and the pilot interviews. Interview questions were pilot-tested with two individuals prior to data collection. The pilot tests informed minor changes to the structure and language of the questions to ensure that that they would be better understood. The semi-structured interviews were written as lists of open-ended questions and topics. In addition, based on the participant’s responses during the interview, supplemental probes were added by the interviewer. The interview guides for the laypersons and the key informants were very similar in their themes. The key informants’ interview guide had two additional prompts about the nature of their job and the capacity of their interaction with the Muslim community.

Data were collected from April to June 2013. Interviews typically lasted 50-90 minutes. Study participants received no financial compensation for the time they devoted to the study. Written consent was obtained from all study participants prior to their interviews. Demographic data were also collected from the participants. The interviews were conducted in a private room at the Cultural Center or in the key informants’ offices. The interview questions were in English and the participants were instructed to answer in English. However, when participants spoke in Arabic, their responses were translated to English when they were transcribed.

Data Analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded and were transcribed verbatim by the principal investigator. Transcriptions were anonymous and assigned only a number. Data analysis first occurred concurrently with data collection using a modified constant comparative method by the principal investigator (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Subsequently, four independent coders, using an open coding strategy, independently coded one transcript and identified emerging themes in the data (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The transcript was then reviewed line-by-line by all coders in a group meeting to establish inter-coder reliability and reconcile differences in codes using team consensus; the codes were only included if three or more coders agreed on them. This resulted in an initial codebook that was used for the subsequent interviews and was updated for emerging categories, constantly comparing emerging categories to each other to determine their nature and significance (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990).

In addition to the inductive approach that was utilized in the first phase of coding, the second phase of coding employed a deductive approach. Data analysis was guided by a socio-ecological theory of behavior (Carnegie et al., 2000). During this phase, axial coding was also conducted to reexamine and establish links between themes identified in the data during the initial analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Data collection and analysis ceased when no new information or insight was forthcoming. Triangulating (Flick, 1992) with the perspective of the key informants, the qualitative data gave good support for the preliminary themes generated from the laypersons, while also raising other different important ones. In all, as the categories were derived from and corroborated across the inquiry, the final set of categories closely fit the data and drew support from both the laypersons’ and the key informants’ responses. The NVIVO software application (International, 2008) was used to facilitate data management.

Results

Participants

Ten laypersons (4 men and 6 women; age = [M = 26.30, SD = 11.53]) and seven key informants were recruited (2 women and 5 men; age = [M = 42.14, SD = 10.63]). All laypersons were US citizens. Their countries of origin included Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt, Syria, Morocco, and Sudan. The key informants included three psychiatrists, one imams, one clinical social worker, and one licensed mental health counselor.

| Lay Persons | Key Informant | |

|---|---|---|

| N=17 | 10 | 7 |

| Gender N (%) | Male: 4 (40%) Female 6 (60%) | Male: 5 (80%) Female 2 (20%) |

| Age in years M (SD) | 26.30 (11.53) | 42.14 (10.63) |

| Country of origin | Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, Morocco, and Sudan | |

| Profession | 3 Psychiatrists, 2 Imams, one Clinical Social Worker, and one Licensed Mental Health Counselor. | |

| % Muslim | 100% | 86% |

Themes

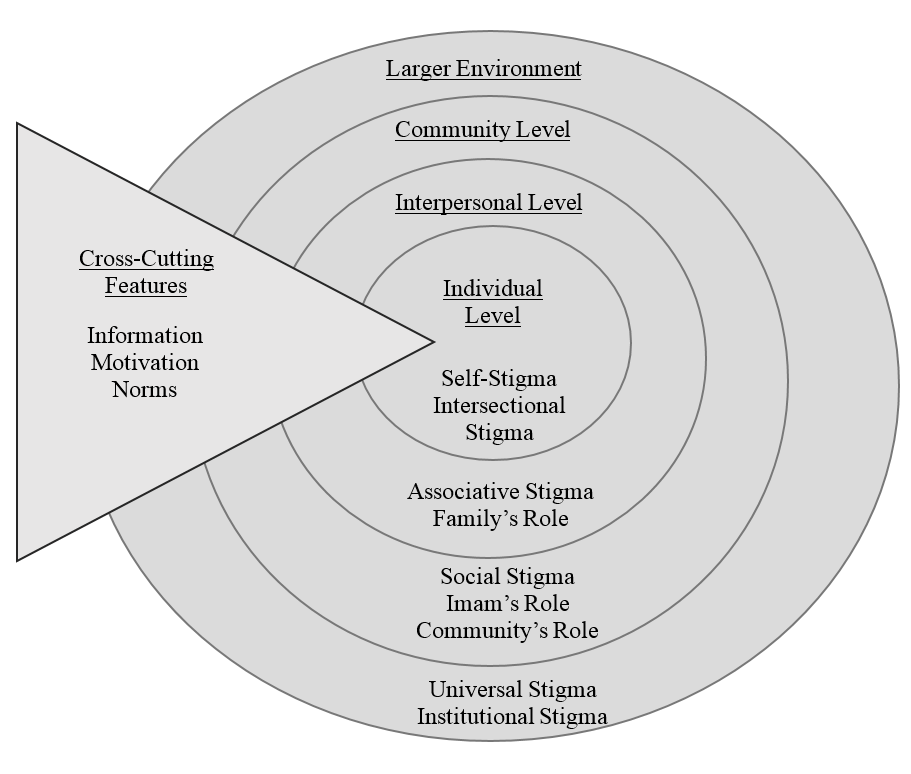

Data analysis yielded six major themes related to the factors that may influence an Arab-Muslim’s decision to seek formal mental health services: stigma, family and community’s role in help-seeking, information, attitudes, beliefs, and norms. These factors were then mapped onto a socio-ecological framework (see Figure 1) that includes the levels: larger environment, community, interpersonal, and individual in section 1. In addition, factors that influenced all four levels were included under a separate category called “cross-cutting factors” in section 2.

Section 1

Stigma

Stigma was identified as a very strong factor and barrier to the utilization of formal mental health care. All lay-participants (n=10) endorsed that a pervasive stigma exists and contributes greatly to the reduced seeking of mental health services within this population. This stigma existed at multiple levels of the person’s immediate and larger environment and took many forms, including self-stigma, associative stigma, social stigma, universal stigma, and intersectional stigma.

Larger environment level: Universal and institutional stigma

Some participants (n=6) explained that, at the larger environment level, exists a universal stigma around mental health issues, not restricted to the Arab-Muslim community, that plays a role in help-seeking behavior within this community. This stigma is reflected in the negative and distorted view of people with mental illnesses and the devaluation of mental health services compared to medical services. They also discussed the institutional stigma that surrounds mental illnesses, which may impact a person’s chances of obtaining a job or being trusted in a position of authority (e.g., the military). Institutional stigma refers to the rules, laws, policies, and procedures put forth by bodies of power that restrict the rights, liberties, and opportunities of the stigmatized group.

Community level: Social stigma

Social stigma comes into play at the community level. The community level refers to the individual and the people directly involved in their community who may reside in a local area or may be part of the same mosque or Islamic center. All lay-participants (n=10) discussed how the stigma at the social level can take many forms. Firstly, mental health symptoms are often dismissed by the community; some members of the community might provide alternative explanations for the behavior while others may deny its existence entirely. Individuals with mental illness might be treated differently, avoided in social situations, or even isolated or ostracized by community members:

“Like if you’re parents and you have children and we’re talking about a child who has a problem, you probably wouldn’t want your child to interact or play with that other child.” (layperson, Participant 4)

Participants described that people with mental illnesses can be the subject of gossip and harsh judgment by the community. People with mental illnesses are often attached negative labels including “abnormal,” “weak,” “lazy,” and “dangerous,” or they are said to be a burden. Therefore, mental illness is a taboo subject and is often kept a secret from the outside community.

Interpersonal level: Associative stigma

Stigma also operates at the interpersonal level, where the individual and his/her close relationships such as their family, close relatives, and friends interact, through associative stigma. Many participants (n=12) described how the stigma may also extend to the family and thus the social repercussions of seeking mental health treatment may be intensified. In addition, participants often discussed the importance of maintaining a good family reputation and social image, as well reporting concerns that the person suffering from the mental illness or their family members, especially females, may become unsuitable for marriage:

“Like if one of my sisters, for example, developed some kind of mental health issue, my parents would help her out but if the issue became public, they would try to probably dismiss any rumors. They’ll be like ‘no, our daughter is fine’ because they’re always thinking about the reputation of the family and how that affects like the latter marital life of my sister.” (layperson, Participant 4)

Individual level: Self-stigma and intersectional stigma

Finally, stigma operates at the individual level, through the internalization of the societal stigma by the individuals themselves. Half (n=5) of the laypersons interviewed described that self-stigma is a common occurrence for individuals experiencing mental illness, who will often endorse the negative labels and perceptions that the community holds about them. This was corroborated by the informants interviewed:

“I think for a person who has mental health needs, the idea that ‘Am I crazy? Am I losing my mind? Am I weird now? Am I no longer part of normality?’” (imam, Participant 13)

Another type of stigma that operates at the individual level is intersectional stigma, which was discussed by the majority of our participants (n=16). In our data, we found relationships between the different identities such as race/ethnic background, gender, or disability and forms of oppression. Arab-Muslims with mental illness experience stigma on many levels that intersect with their different identities:

“I was just seeing a patient who has autism and he gets bullied all the time and it’s because he’s different so anybody who’s perceived as being different is a target of bullying… and then there is the issue related to racial, ethnic, religious differences, where somebody perceived to have a different color, somebody perceived to have a different religion could be targeted.” (mental health professional, Participant 11)

The following participant, who experienced depression, describes what it was like to serve in the US Army as a Muslim and experience mental illness:

“In my opinion what causes some depression in some people’s lives is like the Islamophobia in the US. When I was in the military, I didn’t tell anybody that I was Muslim… a lot of the times people like other soldiers who would like I don’t know associate me with the people that we were fighting against… I did get a little bit annoyed by it which stressed me out.” (layperson, Participant 3)

Stemming from intersectional stigma, participants described issues revolving around identity to be impactful on their health. Some participants discussed issues related to acculturation or personal exploration of self and religious beliefs. Many participants also discussed gender (n=6) as a factor that further contributed to the stigma of mental illness. We found that the intersection of being an Arab male and having mental illness to be very different than the intersection of being an Arab female and having mental illness. Women and men in the Arab community have different expectations of their reactions to stress; we found a strong link between the perception of weakness and subsequent stigma that females and males deal with in the community. Many participants endorsed that Arab-Muslim men would face a harsher stigma if they sought mental health help than would women. In some Arab cultures, rojola or masculinity has specific characteristics such as strength, courage, and domination. Participants explained that due to this rigid construction of masculinity, the community might view men who experience mental health symptoms as weak:

“I think it completely almost near impossible for a guy to go to his friends and tell them that you’re depressed, I think it’s very difficult…Because the whole concept of rojola (masculinity) right? Or ‘moroa’ (bravery), you’re supposed to be stern and tough.” (layperson, Participant 7)

On the other hand, some participants discussed how women are viewed as naturally overly emotional and weak. This often resulted in the trivialization of women’s mental health symptoms and perceiving them as cries for attention rather than genuine suffering:

“She could be telling me that she’s bulimic to get my attention … I don’t know if she had the symptoms I mean she just verbally told me ‘I’m throwing up.’” (layperson, Participant 6)

Family and community’s role in help-seeking

Interpersonal level: Family’s role

At the interpersonal level, the family’s support or lack thereof affects whether the person will seek mental health care services. Eight out of the 10 laypersons interviewed described how the family strongly influences whether an individual seeks help or not. In more extreme cases, whether the person wanted to go or not was irrelevant in the family’s decision. Participants stated that if a family supports the decision to seek professional help, the individual is more likely to seek services. The family's influence often extends into major decisions such as the use of psychiatric medications; this was corroborated by five of our seven informants. One mental health professional described how Arab-Muslims might choose to do something for the benefit of their family rather than for their own benefit, including not going to mental health treatment:

“I think a lot of the not-western, the eastern, sort of cultures operate from a ‘we’ mentality… what is good for the family, the family first, community first, not ‘me first’. (mental health professional, Participant 17)

Community level: Community’s role

Six lay-participants explained that community social support can be an influential factor and depending on the community, can either provide an environment that endorses help-seeking or discourages it:

“[Be]cause if your community supports you getting help, if the community is supporting mental health...having these events and publicizing them widely, if the imam is talking about it openly, it makes it less weird, less big, less dangerous, less crazy, less all of these negative things and makes it more normal, more okay, more every day. I think that helps.” (mental health professional, Participant 17)

Another factor that could influence help-seeking behavior is the feedback that one receives after seeking treatment from family or community members. Participants explained that if an individual in the community openly seeks professional help and is later told by someone in the community that they appear to be doing better, that this type of positive feedback is a powerful affirming experience for the individual seeking services:

“When I started seeing them [mental health services], he [my friend] was the one that affirmed to me that actually it's working in a sense...he was like, ‘what’s up with you? I was like “what?” He’s like ‘I don’t know, you just seem like you're in a good mood.’” (layperson, Participant 7)

On the other hand, participants revealed that the community can be discouraging in two ways: by not providing an environment where seeking services is openly acceptable, and through a lack of engagement because they perceive mental health to be a private matter that should stay within the family, or else because they feel unequipped to be involved in these matters.

Community level: Imam’s role

All key informants (n=7) interviewed endorsed that the imam can play a large role in the Muslim and Arab community. Each mosque usually has an appointed imam that serves as a leader of the mosque community and provides pastoral services such as counseling. Participants endorsed that the responsibility falls upon the religious leader to assess if people coming to him require mental health treatment, reassure them that seeking mental health treatment is permitted by religion, and, when needed, personally refer them to mental health providers:

“In my job at that juncture is just to say ‘it’s ok to seek medical help, it’s religiously commendable or even obligatory for you to seek someone who can help you with this problem.’” (imam, Participant 13)

Both imams interviewed discussed the essentiality of being aware of their own professional limitations and their inability to provide mental health care to people who might have mental illnesses; relatedly, a lack of awareness was identified as a hindrance:

“I’m not a counselor, I’m an imam and I know the difference between the two…. you’re in the position of posturing, feigning knowledge, faking to understand something that is medical and you’re not a medical professional yourself…[you tell yourself] ‘I’m not an imam if I don’t know every answer, just make something up, just say something you’re an imam, you’re supposed to know.’” (imam, Participant 16)

Section 2

Cross-cutting factor: Mental health literacy

Some participants stated that educated Arab-Muslims are less likely to endorse stereotyped views of mental illnesses and that they are more likely to seek mental health treatment when faced with stress or mental health issues. Other participants discussed how people with “lower levels of education” are less likely to support seeking mental health treatment, and are more likely to hold traditional and supernatural beliefs about the nature of mental illnesses and subsequently seek religious healing or no treatment at all:

“I realize that the people who kind of blame these things on demonic possession, they tend to be not as well-educated.” (layperson, Participant 5)

This was corroborated strongly when almost all the informants (n=6) identified the need for increased education, especially mental health education, in the Arab-Muslim community. Furthermore, they believed that increased education about various mental health issues would serve to de-stigmatize mental illness:

“I think people need to get used to hearing about mental health issues. If you can hear it and tolerate it, maybe you can talk about it.” (mental health professional, Participant 17)

Informants revealed several methods that would serve to remove the stigma of mental illness in the Muslim community. The first was to have people with mental illnesses who have sought help share their experiences with members of the community. In addition, informants mentioned packaging, wherein therapeutic methods are incorporated or disguised in religious language, as well as incorporating educational programs into everyday contexts, including Friday prayer sermons:

“Having people who have come out of the program [mental health treatment] saying ‘I went to program,’ testimonials…And ‘it helped me!’” (imam, Participant 13)

“We disguise by packaging the same remedies, strategically we disguise them, we disguise them in language of religion.” (imam, Participant 16)

Fourteen participants either endorsed or identified commonly held misconceptions about the nature of mental illnesses, including the notion that unless there are obvious somatic complaints, the person is healthy. Participants cited leading an unhealthy lifestyle and having frequent mood swings as reasons someone might be diagnosed with mental illness. Participants (n=8) discussed the common belief in the Arab-Muslim community that depression is a not a real mental illness. Reasons underlying this belief include that the person is just sad, can easily get over it, or has lost connection to Allah:

“I think depression can actually be solved very easily through religion through ‘ibadah’ (worship), through remembering Allah through ‘Thikr’. [Be]cause when you’re close to Allah, how can you be sad?” (layperson, Participant 1)

Other misconceptions were that schizophrenia is a multiple-personality disorder, that bipolar is the result of bad parenting practices (e.g., parents spoiling their children), and that eating disorders are only a phase, are a ploy used by women and girls to gain attention, or are just girls “watching themselves and trying to look pretty.” Finally, participants stated that people who have suicidal ideation are judged harshly and perceived to be weak both mentally and in their faith by the Arab-Muslim community. This is because of the Islamic belief that those who commit suicide are said to be condemned to suffer in the afterlife:

“I feel like they (people who commit suicide) gave up too fast…God doesn’t give you more than you can handle.” (layperson, Participant 10)

We explored the sources where participants may have gotten information about the nature of mental illnesses, their treatments, or people with mental illnesses. These sources may portray a stigmatized, stereotyped, or inaccurate image of these topics. We further investigated how these sources may have a positive or negative influence on participants and the community’s help-seeking behavior. The most frequently cited source of information by participants was the media. Most participants (n=6) discussed several negative, stereotyped images of people with mental illnesses, including their portrayal as “weird” people with obsessive behaviors and dangerous people off their medications, as well as the stereotype of the underqualified psychologist. Two participants discussed how channels such as YouTube are helping perpetuate the belief that Jinn (spirits) exist and are responsible for psychosis-like symptoms by providing access to videos of Arabic programs about the topic of possession or amateur videos taken by individuals supposedly witnessing an exorcism:

“They’re all over YouTube, it’s people who claim to be possessed and then they have exorcisms and it’s always a Jinn inside of them….media culture has penetrated into the minds of Arab society into thinking that mental illness equals possession or demonic possession.” (layperson, Participant 5)

None of the lay participants mentioned the media being a positive source of information about mental health. On the other hand, two informants discussed how the media increased the visibility of mental health through shows like “Frasier,” and may have promoted more positive attitudes towards mental health in the community.

Cross-cutting factor: Attitudes

Seven laypersons stated that they endorsed seeking formal mental health services. However, two participants appeared to be providing socially desirable answers and, when probed further, revealed they could not think of a situation in which someone might need mental health services. In addition, another participant endorsed help-seeking for others and not for herself, stating:

“I would tell other people to do it, I don’t know if I would apply it to myself just because I’m not usually like comfortable going into depth about that type of stuff.” (layperson, Participant 5)

Six lay-participants had used formal mental health services. They described having either negative or positive interactions with services, but most stated they experienced both:

“It helped a lot! And I admit it now but what made me [go] against it is like because of the stereotypes that develop around it.” (layperson, Participant 7)

Almost all participants (n=15) stated that Arab-Muslims often do not support the use of psychiatric medications. Most laypersons (n=6) did not endorse the use of medications for themselves. Reasons stated included that medications are used as a commodity, a short-time fix, and can cause life-long dependence. The majority (n=6) of the informants interviewed corroborated the concerns voiced; a layperson explained that these concerns may cause Arab-Muslims to refuse medications:

“The medicine that we are given has so many side effects. It’s because it’s a commodity…they give you this medicine to take and then you get to take more medicine due to this medicine…I even believe that depression medicine makes things worse for people so that they can keep taking depression medicine.” (layperson, Participant 1)

Two of the laypersons interviewed had used psychiatric medications in the past and stopped because of the side effects:

“It just makes you more depressed, makes you nauseous, makes you have bad nightmares.” (layperson, Participant 5)

All participants discussed some level of skepticism around mental health treatment, including questioning the legitimacy of the field, mental health providers, and psychopharmacological medication. Participants were skeptical of mental health professionals for several reasons. Some participants (n=6) stated that some Muslims might be skeptical of a non-Muslim mental health provider because they feared linguistic, cultural, and religious misunderstanding or even discrimination. In addition, Muslims may be skeptical of taking their children to non-Muslim mental health professionals for fear that providers would brainwash them and normalize cultural and religious taboos like dating and drinking alcohol. This was corroborated by all the informants:

“...not trusting mental health providers, many families talk to me that ‘I’m afraid that if my teenager goes to a therapist, he’s gonna tell him go date and go have sex, and go try drugs … some misunderstandings around what therapy is about and what psychology is about. Some people think that it’s an alternative religion or it’s a substitute for one’s faith.” (mental health professional, Participant 12)

Some lay-participants (n=5) also explained reasons that dissuaded them from seeing Muslim clinicians, including that the clinician’s religious beliefs could potentially impact their advice, or that they would feel judged for misbehavior by the clinician:

“No, I do not prefer that, because I’d like to hear the insight of someone who’s just professionally trained to do that and hear what they have to say from an outside perspective…I worry sometimes about the religious beliefs to kind of impact their advice or what they say.” (layperson, Participant 6)

Many participants expressed discomfort with the idea of seeing their therapists in the same immediate community as family members and friends. They described feeling hesitant toward receiving care from community members, citing fears that patient confidentiality might be breached or that knowledge of their mental health issues might circulate around the community, tainting their image or reputation.

Beliefs

Participants discussed several beliefs that Arab-Muslims hold about the causes of and the appropriate treatments for mental illnesses including bio-psycho-social, religious, and supernatural narratives.

Bio-psycho-social narrative

When asked about the causes of mental illnesses, all participants endorsed the causes of mental illnesses as either biological, environmental, genetic, or some combination of the three:

“A mental illness… like chemical imbalance in the brain.” (layperson, Participant 3)

“...a biological condition” (layperson, Participant 5)

“…life traumatic experiences and genetic diseases.” (layperson, Participant 10)

Many (n=9) discussed additional alternatives explanations, religious and supernatural, for the causes of psychological symptoms.

Religious narrative

Thirteen participants discussed some of religious beliefs that the community has about the causes of mental illnesses. They went on to discuss which beliefs facilitated or hindered help-seeking behaviors. Eight participants discussed how many of those who display symptoms of mental illness are often accused of having weak faith or losing connection with God. They are usually encouraged to strengthen their religion and to pray more instead of seeking formal mental health services. Often, if symptoms persist despite the person praying, she/he is accused of “not trying hard enough”:

“I feel like it’s easy to say that it’s just they have a weakness in faith a lot. I’ve heard that a number of times ‘Oh this person must just have a weak iman (faith)’ … ‘Oh they must have weak faith, so let’s send them to the masjid,’ that might help to some degree but not completely so.” (layperon, Participant 4)

Eleven participants discussed the belief that afflictions, mental illnesses included, are ordained by God. Thus, they are perceived as the result of God’s will and have a purpose to them. Five participants discussed how the belief that a mental illness is a test of one’s strength and endurance could encourage a person to accept their diagnosis and seek formal help:

“[The belief] could help them build strength in dealing with it if they perceive this as a test that they have to go through and that it needs their strength and courage.” (mental health professional, participant 11)

On the other hand, eight participants discussed how the same belief could be perceived differently. They stated that if people believe that mental illness is a test of their patience, they are more likely not to seek help at all or will utilize religious coping strategies such as praying. They discussed the beliefs that it is important to trust God’s will and plan for you, that God does not give you more than you can handle, and that seeking formal mental health care may be perceived as complaining against God’s plan:

“I’m complaining then maybe I’m not being a loyal servant or like a good Muslim.” (layperson, participant 9)

Some participants (n=5) discussed some widely accepted prophetic teachings and sayings that may facilitate help seeking behavior in the community. “Le kuli da’a dawa’a” (For every illness, there is cure/medicine) and “Ya ibad Allah tadawo” (Oh servants of God, seek remedies) are both widely accepted Prophetic sayings that can be used to support help-seeking behavior in the Arab-Muslim community. Key informants speculated that it is likely that uneducated, deeply religious, or immigrant Arab-Muslims may feel that only God can cure illnesses and feel that they have failed religiously if they seek medical help. Thus, these two Prophetic sayings among others can be used to reduce the feelings of guilt or shame that might be associated with seeking help.

“‘Oh people, seek remedies for your illnesses’ I mean that’s a clear principle in Islam... so you just kind of remind people... we believe that we should go out and seek remedies for our illnesses and then they go for it. Then you have the statement for every illness there is a cure.” (imam, participant 13)

Supernatural narrative

Only one participant endorsed that mental illnesses may be caused by demonic or satanic possession. However, other participants (n=11) mentioned that this is a prevalent belief in the Arab-Muslim community. Participants explained that spirits, known as Jinn, are believed to possess a person and may be good or evil. Evil spirits are sometimes referred to as shayateen or devils. Participants discussed the telling symptoms of possession to include speaking multiple foreign languages, levitation, as well as multiple mental and physical symptoms like incoherence, nausea, and sweating:

“I honestly truly believe that mental illness and ‘Shaytan’ (Satan) go hand in hand.” (layperson, participant 1)

Other participants discussed additional supernatural causes believed to cause mental illness including black magic, curses, and jinxing. One participant explained that people may be superstitious and fear talking about mental illness because they think it might happen to them or they might “catch it”. Furthermore, five key informants endorsed that many Arab-Muslims believe that the “Evil Eye”, or hostile envy, may cause mental and physical illnesses:

“The evil eye, that people looked at you because you’re doing so well and so in my culture we say don’t praise people too much, don’t say they’re perfect because something bad can happen … and this is why it’s very hard for Westerners to understand when they deal with our mental illness. It’s because mental illness can be seen as the outcome of being really good.” (mental health provider, participant 15)

Cross-cutting factor: Gender norms

Several participants (n=10) described how gender norms may influence help-seeking behavior in the Arab-Muslim community. Some Arab cultures’ definitions of femininity and masculinity have help-seeking expectations attached to them. Some participants discussed how the concept of masculinity makes it harder for Arab men to seek help because they are expected to tough it out. Others participants discussed how an Arab-Muslim woman seeking help would be much more accepted because they are viewed as overly emotional and weak. However, it should be noted that both women and men are judged for seeking help:

“If it’s a female, they’re gonna assume she’s just being weak, she has PMS….with the man, they’ll say “oh you need to be a man and take it” ...like they’ll think if it’s a woman like by nature she’s supposed to need emotional help or mental help. But for a man, it’s probably worse if it’s a man.” (layperson, Participant 5)

Discussion

In this study, we were interested in investigating attitudes that some Arab-Muslims in the US hold about help-seeking when faced with stress or mental health issues, exploring the community perceptions about mental illness, its causes, and its treatments, as well as identifying potential cultural and religious facilitators and barriers to seeking formal mental health care. The qualitative nature of this study provides an in-depth and holistic understanding of the attitudes and beliefs that some Arab-Muslims living in the greater Boston area hold toward mental health. This study provides a deeper understanding of this subgroup by elucidating the relationship between their attitudes, values, and cultural/religious beliefs and practices and as a result, their help seeking behavior. This understanding is essential in highlighting potential barriers to utilization of mental health services among Arab/Muslims in the US. This study also adds to the current literature of Arab-Muslims’ mental health help-seeking behavior in the US by identifying novel themes not discussed in previous research and expanding on themes that have been identified.

We used a socio-ecological model (see Figure 1), loosely based on the socioecological model for change by Carnegie and colleagues (2000), to elucidate the multiple environmental levels that can be employed to change behavior in the Arab-Muslim community. In the model, we have organized the themes identified in the results section into four levels: individual, interpersonal, community, and the larger environment level; these may act as facilitators or hindrances of an individual’s help-seeking behavior. This model highlights the multi-level nature of the factors that may interact to influence a person to decide whether to seek formal mental health care or take a different action course. This decision is made by the person as well as by the people around them including their family, their community, and the larger environment in which they reside. Through our analysis we identified factors that may act as facilitators or hindrances of help-seeking behavior, with some factors acting as both.

Stigma was a pervasive theme that was identified in all levels of our model. On the larger environment level, participants identified the stigma of mental illness, of the field of mental health, and of mental health professionals that pervade all communities in the United States, both mainstream and subgroup. Also on the larger environment level is intersectional stigma or double stigma, which is the idea that individuals who belong to racial and ethnic minority groups may be experiencing the stigma of mental illness on a more complicated level (Jones & Corrigan, 2012). Our participants discussed the compounded negative effects of holding multiple identities of oppression including race, gender, sexual orientation, class, and mental illness. On the community level, participants identified social stigma, which is when society, the public, or large social groups endorse the stigma of mental illness, its stereotypes, and may discriminate based on these negative attitudes (Watson & Corrigan, 2001). On the interpersonal level, participants identified associative stigma, which is when the public stigmatizes the family and friends of a person with a mental illness by association (Watson & Corrigan, 2001). On the individual level, participants discussed self-stigma, which is when individuals turn against themselves because they are members of a stigmatized group (Watson & Corrigan, 2001). In all cases, participants stated that stigma acted as a strong barrier to seeking formal mental health care.

Universally, societies stigmatize people with a mental illness. However, the social stigma of mental illness in an Arab community is unique; due to the collectivist nature of this community, this stigma has an amplified impact. The data revealed that associative stigma is particularly impactful on an individual with mental illness and the associated family members. The community may label people with mental illnesses as majnoon (crazy) and views them as contaminators of their family’s reputation (Youssef & Deane, 2006). Thus, through the process of associative stigma, society openly scrutinizes the family of a person living with a mental illness (Watson & Corrigan, 2001). We found that associative stigma influenced the family’s involvement in the reasoning for or against and the process of seeking and receiving mental health services. Research has suggested that family members may discourage the member suffering from a mental illness from seeking treatment or professional help as a means of ensuring that the family name is not tarnished (Youssef & Deane, 2006). This may result in patients seeking treatment when they have reached acute stages of their mental illness, resulting in greater and longer lasting effects.

On the other hand, our findings suggest that the individual might internalize the social stigma in a process known as self-stigma. Self-stigma is the internalization of the public’s stigma about normalcy, sanity, and thoughts about a person’s ability to fit into society (Watson & Corrigan, 2001). There are three components of self-stigma: awareness of the stereotypes, agreement with them, and application to one’s self. A person may deem themselves useless, unwanted, and blame themselves for their illness. The subsequent decrease in self-efficacy and self-esteem will likely affect their willingness to seek treatment. As suggested by Corrigan (2009), the decrease in self-esteem and self-efficacy will create the “why try” effect whereby people with mental illnesses may have diminished life goals and thus fail to pursue life opportunities and effective treatment; other studies have found this link as well (Vogel, Wade, & Haake 2006).

In the instance in which an individual does seek treatment, a factor that we found to have an affirmative influence on help-seeking was positive feedback. Positive feedback is defined as comments on a positive change or encouragement that an individual receives from family members or people in the community after seeking treatment. Such statements have been revealed to be very powerful and influential in whether an individual will continue to seek treatment or will encourage others to seek treatment. We found this to be greatly related to community social support. The data revealed that the community or environment endorsing and encouraging help-seeking can be a major facilitator. Community social support includes the encouragement of local imams and religious leaders, as well as general acceptance and understanding within the community. More specifically, our findings suggest that there is a crucial role that the imam plays in facilitating help-seeking (Abu-Ras, Gheith, & Cournos, 2008). Because imams are usually the first line of care for religious Muslims regarding mental health issues, the imam’s encouragement and support as well as the direct connection to mental health resources can facilitate the uptake of services.

Imbedded within our model of the factors that may influence help-seeking behaviors are cross-cutting factors that cross-affect all levels of the model. Of the themes we identified, we believe that the themes of information, attitudes, beliefs, and gender norms are cross-cutting factors because they may influence the individual directly and/or influence one of the other levels that may in turn affect the individual. More broadly, we identified a larger theme that combines the themes of attitudes and beliefs, which is motivation. Both the attitudes that the Arab-Muslim holds about mental illnesses and mental health treatment as well as beliefs about the causes of mental illnesses will likely motivate or hinder them to seek formal mental health care.

Almost all participants discussed the lack of mental health education as a hindrance to help-seeking in the Arab-Muslim community. Common misconceptions found in the community appeared to be related to the dismissal or trivialization of symptoms. These misconceptions resulted in actions such as denying that depression is a real mental disorder (Youssef & Deane, 2006) and exhibiting harsh judgment to those who experience suicidal ideation, perceiving them as weak in faith or strength (El Islam, 2008). We speculate that this dismissal is related to the somatization of mental health symptoms as well as the attribution of these symptoms to supernatural or religious causes. The delicate interplay between mental illness and somatic symptoms has been raised as a concern in past research. Ypinazar and Margolis (2006) found that good health was equated with lack of visible symptoms, with participants showing limited understanding of “silent” diseases. Moreover, Al-Krenawi (2005) found that mental health patients tend to express their psychological symptoms in physical ailments as to avoid the stigma that is carried with admitting mental illness.

Participants endorsed that many educated Arab Muslims worked in health fields and were thus more likely to be exposed to the mental health services. However, several studies have found that the stigma of seeking mental health services was consistent across all levels of education and socioeconomic statuses (Aloud, 2005; Youssef, 2007). One possible explanation for this discrepancy in the findings is that lack of education described by our participants might be restricted to mental health literacy rather than a general lack of education. Mental health literacy as defined by Jorm and colleagues (1997) refers to the knowledge and beliefs about mental illnesses and treatments, which may aid in their recognition, management, and prevention. Participants discussed that it was the mystery of what to expect from therapy, the causes of mental illnesses, and what a person with a mental illness might look like. All of our informants endorsed the need for increased mental health education in the community and the need for the use of the contact approach (Jones & Corrigan, 2012), where people are directly exposed to those who experienced mental illnesses and sought treatment for it. Studies have suggested that an increase in mental health education in the population might reduce stigma and assist prevention, early intervention, effective self-help, and support of others in the community (Jorm, 2000; Sewilam et al., 2015).

Our participants also discussed multiple sources of information through which people in the community receive knowledge about mental health. The main source identified was the media, which was discussed as both a facilitator and hindrance of help-seeking behavior. A few informants discussed how psychologists and psychiatrists playing lead roles on TV shows have normalized the discipline in the past few decades. However, the media is often a source of negative portrayals of people with a mental illness (Wahl, 1997), which is what the majority of our participants endorsed. Violent, dangerous, or childish portrayals of people with mental illnesses in the media impacts the public opinion toward them and may attribute to the social stigma of mental health. This might cause people to delay or not seek treatment because they fear becoming like those sensational portrayals in the media.

Having mental health information alone is not enough to drive change, the person needs to be motivated to seek help. The first factor that influences a person’s motivation to seek formal mental health treatment is his or her attitude. In this study, the attitudes we identified included personal opinions or feelings that participants may hold toward mental illnesses, mental health care, or help-seeking. Our analysis revealed that there is a strong sense of skepticism related to mental health treatment, mental health providers, and psychopharmacological medication in some Arab-Muslim communities, which may negatively impact help-seeking behavior. This skepticism was primarily related to medication; there is evidence to support our analysis that a striking majority of the participants expressed skepticism toward psychological medication (Dilman, 1978; Fischer et al., 2010; Youssef, 2007). These negative attitudes about medications will likely lead to people not seeking medical help or not complying with any medication regimen recommended to them (Fischer, Joyce Lii, & Shrank, 2010).

There is also an overarching skepticism over mental health providers and services in general (Youssef, 2007; Aloud, 2005; Eapen & Ghubash, 2004; Erickson & Al-Timimi, 2001). Our findings revealed skepticism about the legitimacy of the field of psychology. Likewise, Eapen and Ghubash (2004) found that one of the main reasons given for non-consultation among Arab Muslims was the skepticism about the usefulness of mental health services. Participants’ skepticism of mental health professionals was directed toward both Arab/Muslim and non-Arab/non-Muslim providers, but for different reasons. Those who preferred mental health providers culturally and religiously similar to them did not prefer non-Muslim mental health providers because they feared discrimination and cultural misunderstanding. There is a fear among some Arab people that they will not be properly understood linguistically or culturally and may experience negative stereotyping by American mental health professionals (Erickson & Al-Timimi, 2001). Many studies have found that underutilization of professional services by minorities might be because the services are controlled by the majority culture (Bizi-Nathaniel, Granek, & Golomb, 1991; Higginbotham & Tanaka-Matsumi, 1991; LaDue, 1994; Wallace, Campbell, & Lew-Ting, 1994).

Participants who endorsed a preference for Muslim providers stated that they do not prefer someone from within their immediate community because they feared the provider would break confidentiality and expose them to other members of the community. One study found that confidentiality was severely lacking in some Arabic-speaking community in because its members had a propensity to share their news and concerns with family and friends (Youssef & Deane, 2006). Our analysis revealed an interesting possible dilemma that may be a barrier to seeking mental health services: Due to the close-knit nature of some Arab-Muslim communities, those who prefer to be treated by someone similar to them culturally may be faced with the paradox of seeking care from someone in their own community. Thus, they may avoid visiting a health professional from within the community due to the possibility of occasional contact in social contexts.

The second factor that may play into the motivation of Arab-Muslims to seek formal mental health care is their belief systems. In our study, we identified several beliefs that participant Arab-Muslims held about the causes of mental illnesses. Studies that found that it is not unusual for people of Arab background to attribute mental health problems to one or more of the following causes: biomedical, human, or supernatural (Al-Krenawi, Graham, Dean, & Al-Taiba, 2004); we found this to be true with our sample of participants. However, these perceptions were not correlated with either positive or negative attitudes toward mental illnesses or endorsement of help-seeking behavior. It is likely that although the participants are aware of different causal explanations, they might endorse some and not others. Therefore, this partial endorsement may cause some to seek formal mental health services and others seek help from religious sources.

These narratives play a big role in determining whether people will seek out mental health services. The idea that “weakness of faith” leads to mental illness, for example, can serve as a hindrance because such societal blame might push the person to believe that the solution lies solely in the strengthening of his faith, as substantiated by Youssef and Deane (2006). In addition, in existing literature, the common religious belief that afflictions are a test from God is considered to have positive connotations, managed with acceptance and patience (Weatherhead & Daiches, 2010). However, in the study it is not clear whether this belief may facilitate or hinder help-seeking behavior; our participant comments reflected acceptance of “God’s will” as both facilitators and obstacles to accessing care. The distinction therefore lies in their interpretation of that will. If a person perceives their mental illness as a test that is meant to challenge their strength and acceptance, they are more likely to seek help. However, if the illness is perceived as a test of patience, patients are more likely to endure their suffering because they believe that is what God intended for them.

Previous research has revealed high endorsement of supernatural narratives, such as the presence of spirits, or Jinn, in the Arab-Muslim community (Erickson & Al-Timimi, 2001; Al-Krenawi, Graham, Dean, & Al-Taiba, 2004). In contrast with this research, only a minority of our participants endorsed this belief. However, most revealed that there does exist a widespread belief among Arabs that the symptoms of mental illnesses can be due to supernatural reasons. It may be that while people have become less likely to endorse Jinn as a cause of mental illness, it continues to carry on in people’s conceptualizations and perceptions of how society packages mental illness. In addition, some Muslims believe the “evil eye” may be another cause of mental illness. The evil eye is “a powerful eye-to-eye gaze and can be dangerous to the envied person, leaving him/her unable to function” (Lauber & Rossler, 2007). Our participants explained that the evil eye is considered by many Arab cultures to be able to cause injury or bad luck for the person at whom it is directed, for reasons of envy, jealousy, or dislike. The belief in a supernatural cause for mental illness plays a hindering role in help-seeking, as it may cause Arab Muslims to seek religious healing treatments.

The topic of gender came up in two of our major themes, specifically, intersectional stigma and societal norms. Societal norms (e.g.: gender norms) specify actions that are expected of individuals by its surrounding society. Our analysis elucidated how gender norms that can exist in the Arab-Muslim community hinder help-seeking behavior for men and women in different ways. We identified a strong link between the perception of weakness and the subsequent intersectional stigma that females and males in the community deal with. Participants explained that the rigid notions of masculinity, which dictates that men should not show emotion and deal with problems by toughing it out, hinders men’s help-seeking behavior. On the other hand, although it might be perceived that the stigma is not as harsh on women, this is untrue. The stigma takes a different form, one of trivialization and dismissal of true suffering. This also likely causes women to not seek help for fear of being perceived as attention seekers and overly emotional.

Limitations

The findings of this qualitative study must be considered with respect to several limitations. Our study sample was self-selected from one Muslim community in Boston and findings may be different for Arab-Muslims in the same or other Muslim communities in Massachusetts and in the United States. As is true for all personal recollections, these participants’ suggestions and opinions may not reflect those of others in the Arab-Muslim community. In addition, social desirability can be particularly problematic in studies using interviews because the participants may be answering in a manner consistent with what they think the interviewer wants to hear (Dillman, 1978). Moreover, selection bias impacted our study results, as 60% of the laypersons that were interviewed sought mental health services at some point, which is not typical for this population. Given that the recruitment flyer specifically used the term mental health, the interested participants may have been motivated to participate in this study because they had used these services in the past. However, this serves our investigation because participants would be sharing their personal experiences rather than speculate about other people’s experiences and therefore, would be offering valuable perspective on the experience of someone seeking mental health services in the Muslim community. On the other hand, it is possible that other Arab-Muslims differ in meaningful ways from the participants who engaged in these interviews. Therefore, interpretations of the results should be taken with caution. Our conclusions are suggestive and not conclusive, and are most likely limited to groups like the one interviewed in this study. The findings from this study provide essential formative and interpretive data for future intervention efforts in aiding Arab-Muslims in accessing and receiving mental health care. Future research is needed to pursue the facilitators and hindrances of help-seeking behaviors with a larger sample and include the views of recent immigrants, older laypersons, and religious healers.

References

- Abu-Ras, W., Gheith, A., & Cournos, F. (2008). The imam's role in mental health promotion: A study at 22 mosques in New York City's Muslim community. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 3(2), 155-176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564900802487576

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Al-Krenawi, A. (1999). Explanations of mental health symptoms by the Bedouin-Arabs of the Negev. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 45(1), 56-64. https://doi.org/10.1177/002076409904500107

- Al-Krenawi, A. (2005). Mental health practice in Arab countries. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 18(5), 560-564. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.yco.0000179498.46182.8b

- Al-Krenawi, A., Graham, J. R., Dean, Y. Z., & Eltaiba, N. (2004). Cross-national study of attitudes towards seeking professional help: Jordan, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Arabs in Israel. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 50(2), 102-114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764004040957

- Aloud, N., & Rathur, A. (2009). Factors affecting attitudes toward seeking and using formal mental health and psychological services among Arab Muslim populations. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 4(2), 79-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564900802487675

- Al-Subaie, A., & Alhamad, A. (2000). Psychiatry in Saudi Arabia. Al-Junun: Mental illness in Islamic world. Madison, Conn.: International Universities, 205-233.

- Alvidrez, J. (1999). Ethnic variations in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Mental Health Journal, 35(6), 515-530. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018759201290

- Beals, J., Novins, D. K., Whitesell, N. R., Spicer, P., Mitchell, C. M., & Manson, S. M. (2005). Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: Mental health disparities in a national context. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1723-1732. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1723

- Bener, A., & Ghuloum, S. (2011). Gender differences in the knowledge, attitude and practice towards mental health illness in a rapidly developing Arab society. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 57, 480-486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764010374415

- Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological methods & research, 10(2), 141-163. https://doi.org/10.1177/004912418101000205

- Bizi-Nathaniel, S., Granek, M., & Golomb, M. (1991). Psychotherapy of an Arab patient by a Jewish therapist in Israel during the Intifada. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 45(4), 594-603. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1991.45.4.594

- Carnegie, R., McKee, N., Dick, B., Reitemeier, P., Weiss, E., & Yoon, C. (2000). Making change possible: Creating and enabling environment in Involving People Evolving Behaviour, eds. MacKee, N., Manoncourt, E., Saik Yoon, C. & Carnegie, R., Southbound Penang y UNICEF: Penang, 158.

- Cheung, F. K., & Snowden, L. R. (1990). Community mental health and ethnic minority populations. Community Mental Health Journal, 26(3), 277-291. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00752778

- Ciftci, A., Jones, N., & Corrigan, P. W. (2013). Mental health stigma in the Muslim community. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 7(1).https://doi.org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0007.102

- Cooper-Patrick, L., Gallo, J. J., Powe, N. R., Steinwachs, D. M., Eaton, W. W., & Ford, D. E. (1999). Mental health service utilization by African Americans and whites: the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area follow-up. Medical Care, 37, 1034-1045. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199910000-00007

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative sociology, 13(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

- Corrigan, P. W., Larson, J. E., & Ruesch, N. (2009). Self‐stigma and the “why try” effect: Impact on life goals and evidence‐based practices. World Psychiatry, 8(2), 75-81. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x

- Corrigan, P. W., Morris, S. B., Michaels, P. J., Rafacz, J. D., & Rüsch, N. (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services, 63, 963-973. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100529

- William Goodrich (2013) Dillman, Don. Mail and Telephone Surveys-the Total Design Method. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1978, Journal of Advertising, 8:1, 52.

- Gearing, R. E., Schwalbe, C. S., MacKenzie, M. J., Brewer, K. B., Ibrahim, R. W., Olimat, H. S., ... & Al-Krenawi, A. (2013). Adaptation and translation of mental health interventions in Middle Eastern Arab countries: A systematic review of barriers to and strategies for effective treatment implementation. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(7), 671-681. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764012452349

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery grounded theory: strategies for qualitative inquiry. Aldine Publishing: Chicago.

- Eapen, V., & Ghubash, R. (2004). Help-seeking for mental health problems of children: Preferences and attitudes in the United Arab Emirates. Psychological reports, 94, 663-667. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.94.2.663-667

- El-Islam, M. F. (2008). Arab culture and mental health care. Transcultural psychiatry, 45, 671-682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461508100788

- Erickson, C. D., & Al-Timimi, N. R. (2001). Providing mental health services to Arab Americans: Recommendations and considerations. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7(4), 308. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.308

- Fadlalla, A. H. (2005). Modest women, deceptive jinn: Identity, alterity, and disease in Eastern Sudan. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 12(2), 143-174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10702890490950556

- Fischer, M. A., Stedman, M. R., Lii, J., Vogeli, C., Shrank, W. H., Brookhart, M. A., & Weissman, J. S. (2010). Primary Medication Non-Adherence: Analysis of 195,930 Electronic Prescriptions. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(4), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1253-9

- Flick, U. (1992). Triangulation revisited: strategy of validation or alternative? Journal for the theory of social behaviour, 22(2), 175-197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1992.tb00215.x

- Hamdan, A. (2009). Mental health needs of Arab women. Healthcare for Women International, 30, 593-611. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330902928808

- Higginbotham, N., & Tanaka-Matsumi, J. (1991). Cross-cultural Application of Behaviour Therapy. Behaviour Change, 8(1), 35-42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0813483900006896

- Holmes, E. P., Corrigan, P. W., Williams, P., Canar, J., & Kubiak, M. A. (1999). Changing attitudes about schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin, 25(3), 447. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033392

- International, Q. (2008). NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version 8).

- Jorm, A. F. (2000). Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 396-401. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.177.5.396

- Kayrouz, R., Dear, B. F., Johnston, L., Keyrouz, L., Nehme, E., Laube, R., & Titov, N. (2014). Intergenerational and cross-cultural differences in emotional wellbeing, mental health service utilisation, treatment-seeking preferences and acceptability of psychological treatments for Arab Australians. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 2015 Aug; 61(5):484-91.

- Kim, B. S. K., & Omizo, M. M. (2003). Asian cultural values, attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help, and willingness to see a counselor. Counseling Psychologist, 31, 343-361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000003031003008

- Koenig, H. G. (Ed.). (1998a). Handbook of Religion and Mental Health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- LaDue, R. A. (1994). Coyote returns: Twenty sweats does not an Indian expert make. Women & Therapy, 15(1), 93-111. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015v15n01_09

- Lauber, C., & Rossler, W. (2007). Stigma towards people with mental illness in developing countries in Asia. International Review of Psychiatry, 19(2), 157-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260701278903

- Lin, T.-Y., Tardiff, K., Donetz, G., & Goresky, W. (1978). Ethnicity and patterns of help-seeking. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 2(1), 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00052447

- Link, B. G., & Cullen, F. T. (1986). Contact with the mentally ill and perceptions of how dangerous they are. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 1986 Dec;27(4):289-302. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136945

- Mackie, F. (1983). Structure, Culture and Religion in the Welfare of Muslim Families: A Study of Immigrant Turkish and Lebanese Men and Women and Their Families Living in Melbourne, December 1982. Australian Government Publishing Service.

- McGuire, T. G., & Miranda, J. (2008). Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care: Evidence and policy implications. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 27(2), 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393

- Meleis, A. I., & La Fever, C. W. (1984). The Arab American and psychiatric care. [Case Reports]. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 22(2), 72-76, 85-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.1984.tb00208.x

- Nobles, A. Y., & Sciarra, D. T. (2000). Cultural determinants in the treatment of Arab Americans: a primer for mainstream therapists. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(2), 182-191. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087734

- Penn, D. L., Guynan, K., Daily, T., Spaulding, W. D., Garbin, C. P., & Sullivan, M. (1994). Dispelling the stigma of schizophrenia: What sort of information is best? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 20(3), 567-578. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/20.3.567

- Penn, D. L., Kommana, S., Mansfield, M., & Link, B. G. (1999). Dispelling the stigma of schizophrenia: II. The impact of information on dangerousness. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 25(3), 437-446. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033391

- Sewilam, H., McCormack, O., Mader, M., & Raouf, M. A. (2015). Introducing education for sustainable development into Egyptian schools. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 17(2), 221-238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-014-9597-7

- Sussman, L. K., Robins, L. N., & Earls, F. Treatment-seeking for depression by black and white Americans. Social Science & Medicine, 1987; 24(3):187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(87)90046-3

- Tobin, M. (2000). Developing mental health rehabilitation services in a culturally appropriate context: An action research project involving Arabic-speaking clients. Australian Health Review, 23(2), 177. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH000177

- Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Haake, S. (2006). Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(3), 325. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.325

- Wahl, O. F. (1997). Media madness: Public images of mental illness. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995.

- Wallace, S. P., Campbell, K., & Lew-Ting, C.-Y. (1994). Structural barriers to the use of formal in-home services by elderly Latinos. Journal of Gerontology, 49(5), S253-S263. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/49.5.S253

- Watson, A. C., Corrigan, P.W. (2001) The Impact of Stigma on Service Access and Participation a Guideline Developed for the Behavioral Health Recovery Management Project. University of Chicago Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation.

- Wang, P. S., Berglund, P. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2003). Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Services Research, 38, 647-673. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.00138

- Weatherhead, S., & Daiches, A. (2010). Muslim views on mental health and psychotherapy. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 83(1), 75-89. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608309X467807

- Wells, K., Klap, R., Koike, A., & Sherbourne, C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001; 158(12):2027–2032. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027

- Youssef, Jacqueline, Arab community and religious leaders' views about utilisation of mental health services amongst Arabic-speaking people in Australia, DPubHlth thesis, School of Health Sciences, University of Wollongong, 2007. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/831

- Youssef, J., & Deane, F. P. (2006). Factors influencing mental-health help-seeking in Arabic-speaking communities in Sydney, Australia. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 9(1), 43-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670512331335686

- Ypinazar, V. A., & Margolis, S. A. (2006). Delivering culturally sensitive care: The perceptions of older Arabian Gulf Arabs concerning religion, health, and disease. Qualitative Health Research, 16, 773-787. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306288469

- Zhang AY, Snowden LR, Sue S. (1998) Differences between Asian and White Americans' help seeking and utilization patterns in the Los Angeles area. Journal of Community Psychology; 26(4):317–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199807)26:4<317::AID-JCOP2>3.0.CO;2-Q