American Muslim College Students: The Impact of Religiousness and Stigma on Active Coping

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This study explored the relationships between the variables of stigma, religiousness, active coping, and religious coping in a sample of American Muslim college students. Structural equation modeling of data from 120 American-born Muslim college students indicated that there is a significantly negative relationship between stigma and active coping, and that the relationship between religiousness and active coping is fully mediated by religious coping. Implications of these findings are discussed in terms of mental health services and supports for American Muslims, and the authors make suggestions for future research.

Keywords: stigma, coping, religiousness, religious coping, Islam, college students

One established view of serious mental illness currently rests within the recovery paradigm, which is based on the work of researchers such as Courtney Harding and colleagues (1987) and suggests that disability is not a continuous state, but is an experience from which one is capable of recovering. Recovery is defined as a journey with a trajectory that can be altered by various factors such as social support, sense of hope, and personal empowerment (SAMHSA, 2005). The approach an individual adopts in an effort to cope with their illness is associated with the empowerment component of recovery. One model of the coping process rests on two factors, approach and avoidance; the former involves an active orientation toward dealing with problems associated with mental illness, and the latter involves tactics oriented away from dealing with illness-related difficulties (Roth & Cohen, 1986). Various types of life stressors call for adopting either approach-oriented or avoidance-oriented coping strategies, with approach-oriented strategies being most efficacious for dealing with stressors that are controllable and persistent. Generally, utilizing approach-oriented (or more active coping strategies) has been tied to positive psychological and physical health outcomes in stressful circumstances, while avoidance coping has been tied to increased distress and chronic disease progression and mortality (Taylor & Stanton, 2007). Promotion of active coping is therefore in line with the recovery paradigm of mental illness.

One form of active, approach-oriented coping with mental illness is service utilization. Research indicates significant underuse of mental health services (Wang et al., 2005), particularly by ethnic minority group members (Sue, Cheng, Saad, & Chu, 2012), including American Muslims (Ball, 1995; Cochrane, 1983). Barriers to treatment that American Muslims face include a perceived lack of culturally competent professionals and issues related to social stigma (Basit & Hamid, 2010). Raja (2005) examined Pakistani-American Muslim men’s attitudes toward treatment-seeking and found that participants were reluctant to seek help for mental health issues due to a fear of the stigma associated with mental illness. Despite an increase in the availability of culturally competent mental health services, many Muslims remain wary of being labeled as a result of the stigma associated with seeking professional psychological help (Haque, 2008). Another study of Arab immigrant women who were victims of abuse found that a majority of participants felt shame in seeking formal mental health services (Abu-Ras, 2003). Some American Muslims may fear that mental health professionals will fail to understand the experiences of embarassment and vulnerability that often accompany disclosing emotional difficulties (Nassar-McMillan & Hakim-Larson, 2003).

On the other hand, studies on the effect of religion on health have yielded several important findings indicating that religion may be an asset for coping with serious health conditions. Religious involvement may be a contributing factor for increased longevity and improved health outcomes (Çoruh, Ayele, Pugh, & Mulligan, 2005) and also has stress-buffering effects in instances where people are experiencing multiple negative life events (Schnittker, 2001). Religion may also promote good mental health through increased social support and a healthier lifestyle due to religious prohibitions of unhealthy habits (Çoruh et al., 2005). Religious coping with depression has been perceived as being relatively effective (Loewenthal, Cinnirella, Evdoka, & Murphy, 2001).

According to the Gallup Survey (2009) American Muslims tend to be more religious than the general population; 80% of surveyed Muslims stated that religion is an important part of their lives, compared to 65% of the overall sample of adult Americans. Research suggests that Muslims in the United States who are young adults are likely more religious than their elders. Pew (2007) found that adult Muslims under the age of 30 are more likely than older Muslims to attend religious services, and younger adult American Muslims are also more likely to express a strong Muslim identity. For instance, 77% of American Muslims ages 18 to 29 report that they are religious, which is higher than the general American population (54%; Gallup, 2009). In a study of 18-to-25-year-old American Muslims, Ahmed (2009) found that they were more committed on average to their religion than were their non-Muslim counterparts.

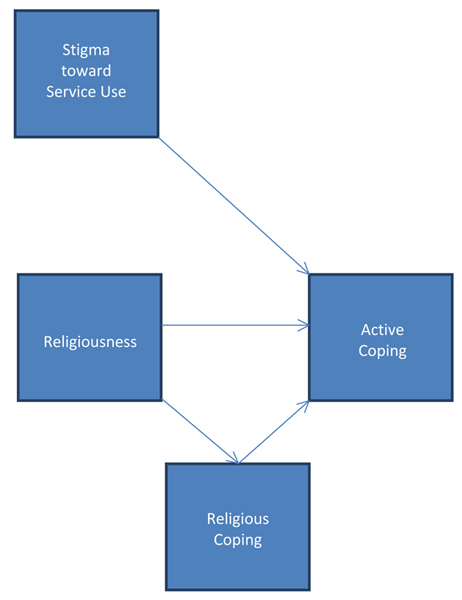

It is important to examine whether religion may function as a coping mechanism for American Muslims dealing with mental illness; the considerations must include findings on the effectiveness of active, approach-oriented coping strategies for dealing with mental illness, the impact of stigma and potential implications for mental health service use in the Muslim community, the demonstration of the potential benefits of religion in dealing with stressful life circumstances (such as serious illness), and the documented levels of religiousness in the American Muslim community. In addition, religiousness may play a role in promoting active coping with regard to mental health issues among American Muslims, despite perceived stigma regarding mental illness and a general reluctance to use mental health services. The current study investigated the relationships between religiousness, stigma about mental health service utilization, and coping styles for American Muslim college students. One hypothesis posited that stigma with regard to mental health service use would be negatively related to active coping, while religiousness would be positively related to active coping, this relationship being mediated by the use of religious coping strategies (see Figure 1).

Method

Participants

Participants for this study were 120 American Muslims who were undergraduates asked to complete an online survey. There were more women (75%) than men (25%). The most represented ethnic and/or cultural background was South Asian (n=59), followed by Arabs (n=26), and White Americans (n=13). There were 8 participants who identified as African-American or Americans from African nations. Participants also came from the following backgrounds: mixed race (n=6), Iranian (n=3), Afghani (n=2), Caribbean (n=2), and East Asian (n=1). In terms of racial and ethnic categories, participants add to more than 120 because some participants reported affiliation with more than one racial or ethnic group. Of the sample, 18 participants (15%) reported being converts to Islam. The mean age of the sample was 20.38 years (SD=2.15).

Participants were offered a choice of compensation for participation in the study: They could choose to receive no compensation, to have money donated on their behalf to a humanitarian agency, or to enter into a drawing for an Amazon.com gift card.

Measures

Stigma Toward Seeking/Receiving Professional Mental Health Services

Stigma was measured using the five-item stigma subscale of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Formal Mental Health Services Scale (ATSFMHS; Aloud, 2004). This measure was adapted from the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale (ATSPPHS; Fischer & Farina, 1995) for a past study of the Arab-Muslim population in the United States. The stigma subscale of the ATSFMHS scale showed good reliability (α =.70) for participants in the present study. Items were answered on a four-point Likert scale (4=strongly agree). An example item is “A person would feel uncomfortable seeking mental health or psychological services because of others’ negative opinions.” Responses to the five stigma items were summed to yield a total score ranging from 4 to 20.

Religiousness

Religiousness was measured using the Sahin-Francis Scale of Attitudes toward Islam (SFS; Sahin & Francis, 2002). This scale is composed of 23 items measuring religiousness in Muslims and has been utilized successfully in studies of mental health (Francis, 2009). The SFS has also been effectively used to measure religiousness among Muslims in several different countries (Francis, Sahin, & Al-Failakawi, 2008). The SFS asks participants to select the most appropriate response to 23 statements regarding their religiousness. Response options vary on a 5-point Likert scale (5= agree strongly). Examples of items are “I find it inspiring to listen to the Qur’an” and “Attending the mosque is very important to me.” Possible scores on this scale range from 23 to 115. The SFS showed good reliability (α =.95) in the present study.

Religious Coping

Religious coping was measured using the Brief Arab Religious Coping Scale (BARCS; Amer, 2005; Amer, Hovey, Fox, & Rezcallah, 2008). This 15-item questionnaire has been used previously to measure religious coping of Arab Americans and asks participants to read each item and select how often they engaged in specified behaviors when they experienced stressful situations or problems. Examples of items include “I prayed for strength,” and “I got help from religious leaders.” Responses vary on a 4-point Likert scale (4=used always). Possible scores on this scale range from 0 to 45. This scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .89 in the present study, indicating good reliability.

Active Coping

Active coping was measured using the Active Coping subscale (AC) of the COPE (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989; Khawaja, 2008). Participants were asked to select responses on a 4-point Likert scale (4=I usually do this a lot) regarding how they typically handle stressful life events. Examples of items on the Active Coping subscale of the COPE include “I concentrate my efforts on doing something about it” and “I make a plan of action.” The Active Coping subscale of the COPE yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .86 in the present study, indicating good reliability.

Results

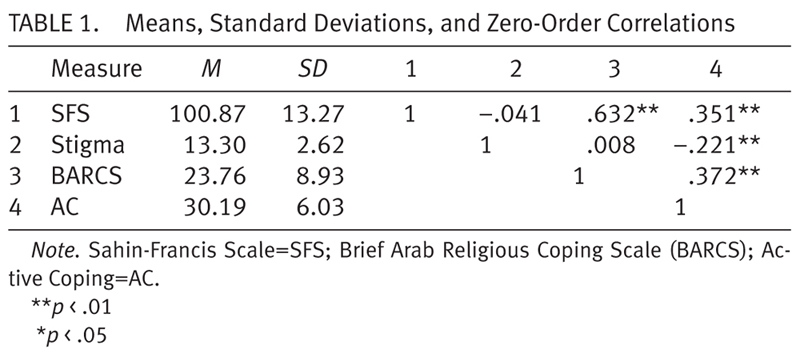

A one-way ANOVA was used to test for effects of race/ethnicity on religious coping. This test revealed there was no significant relationship between race/ethnicity and religious coping, F (1,118) = .007, p= .935. Table 1 shows means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations for the overall scales. As expected, the zero-order correlations showed that stigma and religious coping are related to active coping, and that religiousness is also related to active coping.

Testing Mediated Effects

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) using maximum likelihood estimation in the AMOS 20 program was used to examine alternative models. Five indices were used to assess goodness of fit of the models: chi-square (χ2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Non-Normed Fit Index/Tucker-Lewis Index (NNFI/TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Of these indices, only chi-square provided evidence of statistical significance. However, unlike most tests of statistical significance associated with chi-square, support for a proposed model is demonstrated with a non-significant value. Specifically, non-significance (p > .05) for a particular model indicates that the observed and reproduced variance-covariance matrices are not significantly different from one another. For the present study, common benchmarks, outside of the chi square, were used to interpret model fit indices: CFI and NNFI/TLI (.95 or greater), RMSEA (.05 or less), and SRMR (.08 or less; Kline, 2011).

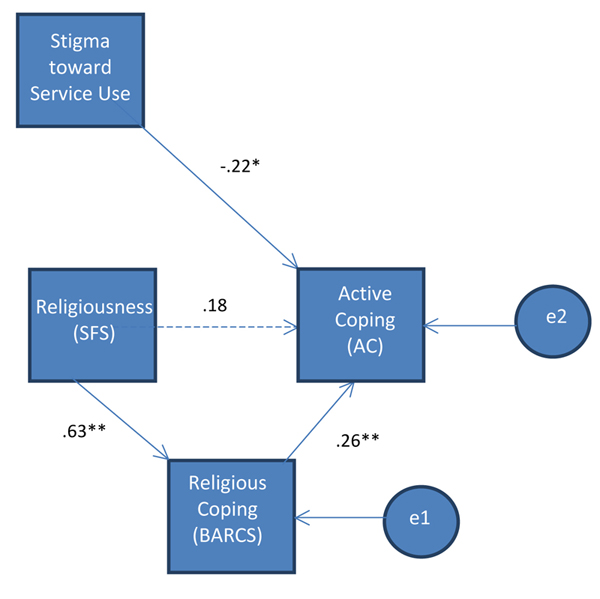

We predicted that stigma would be negatively related to active coping and that religiousness would be positively related to active coping, with this relationship being partially mediated by religious coping (see Figure 1). The path model used to test this hypothesis resulted in a nonsignificant chi-square, and the corresponding fit indices showed excellent fit to the data, (χ2(2) = .43, p > .001, CFI = 1.00, NNFI/TLI = 1.057, SRMR = .0137; RMSEA = .000). The standardized path coefficients for this model can be found in Figure 2. Effects for this model indicate that stigma predicted active coping (β = -.22, p < .001), and that religiousness predicted religious coping (β = .63, p < .001), which in turn predicted active coping (β = .26, p < .001). These results indicate that research participants who reported higher levels of stigma were less likely to use active coping strategies to deal with mental health concerns. Additionally, these results indicate that students who reported higher levels of religiousness were more likely to use religious coping mechanisms, and that these religious coping mechanisms were related to high levels of active coping. It is important to note that the parameter representing the direct effect of religiousness on active coping was not significant.

Discussion

Using SEM, this study examined the relationship between stigma and religiousness on active coping among a sample of American Muslim college students. Additionally, the mediating effect of religious coping on the relationship between religiousness and active coping was examined. Results indicate that, while stigma is negatively associated with active coping, religiousness is positively related to religious coping, which, in turn, is positively related to use of active coping strategies. Therefore, results suggest that religiousness is related to active coping among American Muslim college students, and that this relationship is fully mediated by the use of religious coping strategies.

These findings substantiate claims that consideration of religion as a critical factor in mental health for American Muslims is important (Cinnirella & Loewenthal, 1999; Kobeisy, 2004). Additionally, these results seem to suggest that, despite the negative impact of stigma on likelihood of actively coping with mental health issues, religiousness may act as a buffer in the face of such stigma, promoting one’s likelihood of adopting active coping strategies by encouraging religious coping. The practical significance of these findings are clear, namely that in order to effectively work with American Muslims with mental health concerns, maintaining religion as a central consideration in the counseling process is essential for promoting recovery. Additionally, despite disparities in the use of traditional mental health services, caused in part by the stigma surrounding mental illness and seeking professional psychological help, these findings illustrate that American Muslims may adopt methods of active coping that go beyond traditional service settings, allowing them to avoid the label associated with such services.

Limitations of these findings include a small sample size and overrepresentation of women in the sample. Further, due to low sample size, multiple indicator measurement constructs could not be used in our path analysis. Future studies would benefit from addressing these issues. Future directions for research include a more detailed investigation into the impact of stigma on treatment seeking in the American Muslim population, as well as the possible impact of religion as a resilience factor, which might protect American Muslims from the harmful effects of stigma. Examination of the potential benefits of employing religion-based counseling techniques with American Muslims engaged in mental health services in order to improve treatment outcomes is of additional importance.

References

- Abu-Ras, W. M. (2003). Barriers to services for Arab immigrant battered women in a Detroit suburb. Journal of Social Work Research and Evaluation, 3(4), 49-66.

- Ahmed, S. (2009). Religiosity and the presence of character strengths in American Muslim youth. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 4, 104-123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15564900903245642

- Aloud, N. (2004). Factors affecting attitudes toward seeking and using formal mental health and psychological services among Arab-Muslim population. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Ohio State University, Columbus.

- Amer, M. M. (2005). Arab American mental health in the post September 11 era: Acculturation, stress, and coping. Dissertations Abstracts International, 66/04, 1974.

- Amer, M. M., Hovey, J. D., Fox, C. M., & Rezcallah, A. (2008). Initial development of the Brief Arab Religious Coping Scale (BARCS). Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 3, 69-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15564900802156676

- Ball, P. (1995). Mental Health and Ethnicity Training Programme. North West London Mental Health NHS Trust.

- Basit, A., & Hamid, M. (2010). Mental health issues of Muslim Americans. Journal of the Islamic Medical Association, 42, 106-110.

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

- Cinnirella, M., & Loewenthal, K. M. (1999). Religious and ethnic group influences on beliefs about mental illness: A qualitative interview study. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 72, 504-524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/000711299160202

- Cochrane, R. (1983). The social creation of mental illness. London: Longman.

- Çoruh, B., Ayele, H., Pugh, M., & Mulligan, T. (2005). Does religious activity improve health outcomes? A critical review of the recent literature. The Journal of Science and Healing, 1, 186-191.

- Fischer, E. H., & Farina, A. (1995). Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: A shortened form and considerations for research. Journal of College Student Development, 36, 368–373.

- Francis, L. J. (2009). Comparative empirical research in religion: Conceptual and operational challenges within empirical theology. In J. Astley & L. J. Francis (Eds.) Empirical theology in texts and tables: Qualitative, quantitative, and comparative perspectives (pp. 127–152). Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004168886.i-408.48

- Francis, L. J., Sahin, A., & Al-Failakawi, F. (2008). Psychometric properties of two Islamic measures among young adults in Kuwait: The Sahin-Francis scale of attitude toward Islam and the Sahin index of Islamic moral values. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 3, 9-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15564900802035201

- Gallup. (2009) Muslim Americans: A national portrait. Washington, D.C.: Gallup.

- Harding, C. M., Brooks, G. W., Asolaga, T. S. J. S., and Breier, A. (1987). The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 718-726.

- Haque, A. (2008). Culture-bound syndromes and healing practices in Malaysia. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 11, 685-696. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13674670801958867

- Kobeisy, A. H. (2004). Counseling American Muslims: Understanding the faith and helping the people. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Loewenthal, K. M., Cinnirella, M., Evdoka, G., & Murphy, P. (2001). Faith conquers all? Beliefs about the role of religious factors in coping with depression among different cultural- religious groups in the U.K. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 74, 293-303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/000711201160993

- MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83

- Nassar-McMillan, S. C., & Hakim-Larson, J. (2003). Counseling considerations among Arab Americans. Journal of Counseling and Development, 81, 150-159. Pew Research Center. (2007). Muslim Americans: Middle class and mostly mainstream. Washington, D.C.: Pew. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2003.tb00236.x

- Roth, S., & Cohen, L. J. (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist, 41, 813-819. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.7.813

- Sahin, A., & Francis, L. J. (2002). Assessing attitude toward Islam among Muslim adolescents: The psychometric properties of the Sahin Francis scale. Muslim Educational Quarterly, 19(4), 35-47.

- Schnittker, J. (2001). When is faith enough? The effects of religious involvement on depression. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40, 393-411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/0021-8294.00065

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2005). National Consensus Conference on Mental Health Recovery and Systems Transformation. Rockville, Md: Department of Health and Human Services.

- Sue, S., Cheng, J. K. Y., Saad, C. S., & Chu, J. P. (2012). Asian American mental health: A call to action. American Psychologist, 67, 532-544. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0028900

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Taylor, S. E., & Stanton, A. L. (2007). Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 377-401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091520

- Wang, P. S., Lane, M., Olfson, M., Pincus, H. A., Wells, K. B., & Kessler, R. C. (2005). Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 629-640. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629