Predicting Reasons for Experiencing Depression in Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims: The Roles of Acculturation and Religiousness

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to examine the influence of acculturation and religiousness on Muslim individuals’ attributions of reasons for having experienced depression. A community sample of Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims (n = 76) completed self-report measures of heritage-culture acculturation, acculturation to U.S. culture, religiousness, and individually and interpersonally oriented reasons for having experienced depression. Religiousness, but not acculturation, predicted lower individually oriented reasons for depression. Religiousness also predicted greater interpersonally oriented reasons for having experienced depression, and heritage-culture acculturation predicted lower interpersonally oriented reasons for depression. No moderated effects were found, suggesting that religiousness and heritage-culture acculturation are independently associated with interpersonally oriented reasons for depression. The results provide evidence that, among Muslims, acculturation and religiousness are differentially associated with types of attributions made for having experienced depression.

Keywords: Muslim, Islam, Depression, Acculturation, Religiousness

Predicting Reasons for Experiencing Depression in Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims: The Roles of Acculturation and Religiousness

Increased immigration rates and current events have elevated the visibility of Muslims living in the United States. However, the role of protective and risk factors associated with mental health outcomes among American Muslims remains an understudied area. Indeed, much research on Muslim mental health has been undertaken using a comparative cross-cultural framework (e.g., Bhui, Bhugra, Goldberg, Sauer, & Tylee, 2004; Çirakoğlu, Kökdemir, & Demirutku, 2003; El-Islam, Moussa, Malasi, & Mirza, 1988; Haghighatgou, & Peterson, 1995; Sayed, 2003; Upmanyu, Upmanyu, & Lester, 2000). This research has been useful in that it has highlighted differences between Muslim and Western European cultures, upon which the vast majority of clinical and research psychology is based. Cross-cultural comparisons, however, sacrifice within-group analysis, and as such cannot examine how individual level contextual factors such as cultural-adaptation processes and religiousness may influence Muslim mental health outcomes. The purpose of the present study, therefore, was to investigate the role of individual difference variables in a group of Pakistani and Palestinian American Muslims’ perceived reasons for experiencing depression. Specifically, the present study focused on the roles of acculturation and religiousness.

Muslim Culture and Depression

Previous research findings suggest that cultural attitudes and behaviors influence Muslim individuals’ perceptions and beliefs regarding depression symptoms, etiology, and course (Bhui et al., 2004; El-Islam et al., 1988; Hamid, Abu-Hijleh, Sharif, Raqab, Mas'ad, & Abbas, 2004). Sayed (2003) argued that a lack of distinction between concepts of the psychological self and the physical body distinguishes Middle Eastern cultures from Western cultures, and as a result psychological distress is described in terms of culture-specific constructs and somatic metaphors. For example, depressed individuals in Arabic cultures have reported subjective experiences of deega (oppression), fikr (morbid brooding/preoccupied thought), and a subjective perception of inability to sense beauty in life, instead of typical Western depressive symptoms of sadness, feeling down, or feeling depressed (Hamdi, Amin, & Abou-Saleh, 1997). Consistent with this conceptualization, principal components analysis of depression symptoms reported by Muslim inpatient samples suggested a four-factor solution of “core” depressive symptoms that clustered according to: (1) symptoms consistent with endogenous depression (e.g., early morning waking, guilt, worse symptom severity in the morning); (2) illness severity; (3) attitudes toward oneself and others; and (4) sleep difficulties (e.g., hypersomnia) and perceptual symptoms (e.g., hallucinations; El-Islam et al., 1988). Mood and affective symptoms such as sadness and anhedonia were acknowledged by participants, but only when asked about these symptoms directly. Hopelessness was not commonly reported, presumably because hopelessness is incompatible with Islamic teachings that God is capable of alleviating all illness.

Muslim cultural behaviors and attitudes may also influence coping techniques employed to address emotional and psychological problems. For example, Haghighatgou and Peterson (1995) found that greater self-reported use of passive coping and lower active coping were significantly associated with greater severity of depression symptoms. There is also evidence to suggest gender is related to mental health outcomes among Muslims. For example, studies of Muslim men and women in psychiatric and primary care setting have found that Saudi Arabian women admitted to emergency room psychiatric care endorsed more family- and health-related stressors, whereas men reported more work- and education-related stressors (Al-Subaie, Marwa, Hawari, & Abdul-Rahim, 1997), and that psychosocial stressors such as perceived financial difficulties, legal separation, and family problems predicted severity of depression symptoms (Hamid et al., 2004).

Acculturation

Acculturation refers to adaptational changes in culturally based behavioral, cognitive, and affective domains of functioning resultant from sustained contact with different cultural groups (Kim & Abreu, 2001; Stephenson, 2000; Zea, Asner-Self, Birman, & Buki, 2003). Modern conceptualizations of acculturation emphasize cultural learning and behavioral adaptation, and incorporate cognitive and emotional components of accessing, understanding, and adopting specific aspects and characteristics of a majority culture while also retaining characteristics of one’s ethnocultural heritage (Miller, Sorokin, Wang, Feetham, Choi, & Wilbur, 2006). Thus, acculturation is best conceptualized as a dynamic, multifaceted construct influenced by contextual and internal factors (Miller et al., 2006; Zane & Mak, 2003). Berry’s (2003) model of acculturation argues that acculturating individuals exhibit specific acculturative styles, which corresponds to the level of adaption to the culture in which one is embedded, as well as the involvement in behaviors and practices associated with their heritage culture. Mental health outcomes may be related to the congruence between acculturation and one’s environment, because psychosocial and behavioral competencies that are valued and learned within a specific cultural context may at times be either adaptive or evaluated as pathological by one’s environment (Ogbu, 1981). Thus, person-environment fit in relation to the contexts of one’s acculturation is of significant importance to understanding mental health from a cultural perspective.

Acculturation has been found to be associated with physical and mental health outcomes among many cultural groups, including Asian Americans (e.g., Hwang & Ting, 2008; Yen, Robins, & Lin, 2000), South Asian Americans (e.g., Kumar & Nevid, 2010; Rahman & Rollock, 2004), and Latino Americans (e.g., Moradi & Risco, 2006; Moyerman & Forman, 1992; Thoman & Surís, 2004), and has been associated with outcomes such as intergenerational conflict, psychological distress, depression, and anxiety across multiple ethnocultural groups (see Balls Organista, Organista, & Kuraski, 2003 for a review). Empirical research of the relationship between acculturation and mental health outcomes among Muslims is comparatively limited, although recent evidence suggests a significant association between the two. For example, studies that have compared samples of Arab American Christians to Arab American Muslims have found Muslims who reported higher majority-culture acculturation perceived greater levels of discrimination than Christians (Awad, 2010); that Arab American Muslims report significantly higher levels of marginalization acculturation style than Arab American Christians (Amer & Hovey, 2007); and that bicultural acculturation is significantly related to lower family dysfunction (Amer & Hovey, 2007).

Compared to the above studies which have investigated association among acculturation and mental health outcomes of Arab Americans and South Asian Americans broadly, there are even fewer studies that focus on cultural adaptation processes among Pakistani and Palestinian individuals specifically. Indeed, a literature search using the terms Palestinian, Pakistani, Muslim, and acculturation, yielded only two empirical quantitative studies. Among Pakistani individuals, stress associated with the process of cultural adaptation, or acculturative stress, was related to lower psychological well-being and poorer subjective general health (Jibeen, 2011). With regard to Palestinians individuals living in Israel, psychological well-being was associated with greater identification with Palestinian cultural background and lower identification with Israeli cultural background (Abu-Rayya & Abu-Rayya, 2009). Thus, even within this limited body of research, evidence does suggest a significant association between acculturation and mental health outcomes among Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims.

Importantly, acculturative processes may contribute to conceptualization of the causes and appropriate treatment of mental illness. Findings suggest that individuals from diverse cultures have native theories regarding culturally appropriate methods of mental health treatment (e.g., Abu-Ras, Geith, & Cournos, 2008; Abudabbeh, 2005; Benish, Quintana, & Wamplold, 2011; Çirakoğlu et al., 2003; Fan, 1999; Furnham, Ota, Tatsuro, & Koyasu, 2000; Gureje, Lasebikan, Ephraim-Oluwanuga, Olley, & Kola, 2005; Hugo, Boshoff, Traut, Zungu-Dirwayi, & Stein, 2003; Nath, 2005). Research also suggests that individuals from diverse cultures exhibit symptoms of depression that are congruent with culturally held beliefs about psychological disorders (e.g., Crittenden et al., 1992; El-Islam et al., 1988; Furnham et al., 2000; Hamdi et al., 1997; Sayed, 2003; Tsai & Chentosova-Dutton, 2002; Yen et al., 2000). Thus, beliefs about mental health are partially based on culturally derived norms by which individual compare their own internal states to others (Kuiper & Cole, 1983). These norms reflect culturally appropriate theories of behavior and competency (Obgu, 1981). Culturally based competencies – behavioral, cognitive, or emotional – may be influenced by the acculturative processes. Thus, acculturation by increased majority-culture acculturation and/or loss of one’s heritage cultural characteristics via decreased heritage-culture acculturation may significantly influence attitudes and beliefs about causes of – and, by extension, appropriate treatment for – psychological disorders.

Religiousness

Contemporary definitions of religiousness refer to individual participation in sacred traditions within the context of systems of beliefs, practices, and values (Connors, Tonnigan, & Miller, 1996; Smith, McCullough, & Poll, 2003; Zinnbauer & Pargament, 2005). Research generally supports a significant association between religiousness and mental health outcomes. For example, in a review of 100 published studies on the relationship between religion and mental health, Koenig and Larson (2001) found that 80% supported a positive relationship between religious beliefs and practices and mental health. Similarly, a large-scale meta-analysis of 147 studies of religiousness and depression found a small but significant negative effect size, suggesting that, across studies, greater religiousness is on average associated with lower depression symptom severity (Smith et al., 2003). A moderated main effect and stress-buffering effect was also found such that, overall, greater religiousness was significantly associated with lower depression symptom severity across all levels of life stress, and the negative relationship between religiousness and depression symptom severity was strongest among individuals who rated their life stress as high.

Religiousness is a cultural construct that occurs and develops within specific cultural contexts (Zinnbauer & Pargament, 2005). As a cultural construct, acculturation influences religiousness, and religiousness may likewise influence acculturation by shaping cultural norms, values, behaviors, and attitudes (Yang & Ebaugh, 2001). This has important implications in terms of psychological treatment and intervention among Muslims. For example, the Islamic concept of umma (community) may influence Muslim individuals to seek help for emotional and psychological distress from persons other than mental health professionals, such as religious and spiritual leaders (Abudabbeh, 2005; Nath, 2005). These individuals may seek someone with knowledge of Islamic culture as well as the language of their community, and as such Muslim religious and spiritual leaders often provide informal therapeutic services to members of their communities (Abu-Ras, Gheith, & Cournos, 2008; Ali, Milstein, & Marzuk, 2005).

Although a limited number of studies have empirically investigated the relationship between religiousness and mental health among Muslims, the extant evidence supports a significant association between the two. For example, intrinsic religiousness has been found to be significantly related to better family functioning and lower depression (Amer & Hovey, 2007). Involvement with religious customs and practices has been found to be associated with lower anxiety and depression (Vasegh & Mohammadi, 2007). Similarly, greater self-reported interpretation of events as significant religious mystical experiences has been found to be associated with lower self-reported depression and anxiety (Ghorbani, Watson, & Rostami, 2007). Religiousness has been found to buffer psychological distress and augment life satisfaction among Muslim women in stressful work environments (Noor, 2008). Self-reported religiousness has been found to be negatively associated with death distress (e.g., death anxiety and death depression; Al-Sabwah & Abdel-Khalek, 2006). Among Palestinians, specifically, greater religious identification is associated with greater well-being (Abu-Rayya & Abu-Rayya, 2009). The aforementioned studies have assessed religiousness using a variety of definitions (e.g., intrinsic religiousness versus involvement in religious practice versus mystic interpretation), yet the consistency of the relationship between mental health outcomes and religiousness even among the current limited amount of research suggests that further investigation of religiousness is critically important to advancing the understanding of Muslim mental health.

Present Study

The research reviewed above suggests that culture influences not only clinical presentation of depressive symptoms but also how individuals cope with and seek treatment for depression. Less understood, however, is specifically how acculturation and religiousness jointly influence attributions and beliefs about depression. The purpose of the present study, therefore, was to investigate the relationship among acculturation, religiousness, and beliefs about depression in a community sample of Muslims. To our knowledge, no prior study has investigated the dual roles of religiousness and acculturation among Muslims. It is hypothesized that acculturation significantly predicts participants’ attributions of explanatory causes of depression. Specifically, it is expected that a) U.S.-culture acculturation will be associated with greater internal, individually oriented reasons for experiencing depression, b) heritage-culture acculturation will be associated with lower interpersonal reasons for experiencing depression, and c) self-reported religiousness will be associated with lower individual and interpersonal reasons for experiencing depression.

Method

Participants

There were 76 (14 female and 62 male) participants, self-identified as Pakistani (n = 25) and Palestinian (n = 51) Muslims, and recruited from a religiously based community organization located in a moderately sized, urban area in the Midwestern United States. The participating community organization serves multiple ethnocultural groups, including Pakistanis, Palestinians, Iraqis, Iranians, Indians, Africans, Eastern Europeans, and Western Europeans. Individuals of Pakistani and Palestinian background were sampled because they were the most prevalent ethnocultural groups represented among the participating community organization. To ensure variability in acculturation, no minimum number of years residing in the United States was required for participation. All measures employed in the present study have been standardized in English. Thus, English reading fluency was required for participation.

Demographic characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1. On average, participants were in their mid-thirties (see Table 1), with ages that ranged from 18 to 80. Nearly two-thirds (n = 49, 64.5%) were married, one-third (n = 25, 32.9%) were single, and 2 participants (2.6%) were divorced. Participants were generally well-educated, with the median education level reported being a bachelor’s degree. More than half of participants (n = 41, 54.0%) had obtained their bachelors degree or higher, 26 (34.2%) had attended at least one year of a four-year college or university, 6 (7.9%) had their high school diploma or high-school equivalency degree, and 3 (3.9%) had less than 12 years of education. The most commonly reported total household income range was between $50,000 and $100,000 (n = 25, 33.3%), and this was also the sample median. A total household income of less than $20,000 was reported by 10 (13.3%) participants. Most participants (n = 57, 75.0%) were born in a country other than that United States, 13 (17.1%) were born in the United States but had parents that were born in a country other than the United States, and 6 (7.9%) did not report their nativity status. Of those participants who reported that they were born in a country other than the United States, the mean number of years lived in the United States was 17.59 (SD = 10.46), and only three participants reported that they had lived in the United States for less than 5 years. The mean percentage of years lived in the United States for foreign-born participants, defined as the quotient of years lived in the United States divided by participants’ age, was 46.1% (SD = 26.69).

Procedure

The present study design was cross-sectional and employed a convenience sample of Muslim community members. The principal investigator attended selected community organization activities, at which the study’s general purpose was briefly explained to community members by an organization representative (typically the imam). Organization members were approached by the principal investigator or by an organization representative to solicit participation. After the researcher obtained written consent from volunteering participants, self-report measures of demographic information, acculturation, religiousness, and beliefs about reasons for having experienced depression were administered to participants. Data were collected individually or in small groups. All data collection procedures were reviewed by, approved, and in accordance with Institutional Review Board (IRB) policy.

Measures

Demographic information. Participants reported the following demographic information: age, gender, ethnic background, highest year of school completed, household income, marital status, nativity status, number of years living in the United States, and nativity status.

Acculturation. The Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale (AMAS; Zea et al., 2003) was used to assess participant acculturation. The AMAS, a 42-item questionnaire, measures acculturation in domains of language competency, cultural identity, and cultural behavior with respect to the majority culture and participants’ heritage cultures. Thus, the AMAS is a bidimensional acculturation measure (Berry, 2003; Rogler et al., 1991). Specifically, the AMAS contains two subscales that assess respondents’ acculturation with respect to acquisition of cultural characteristics associated with the majority culture, or United States (U.S.) culture, and retention of cultural behaviors and characteristics of one’s heritage culture. AMAS items are measured using a Likert scale that ranges from 1 (Strongly disagree or Not at all) to 4 (Strongly agree or Extremely well). U.S.- and heritage-culture acculturation score are obtained by computing the average of corresponding subscale items. Subscale scores range from 1 to 4, with higher scores reflecting greater acculturation. In the present study U.S.- and heritage-culture acculturation scores were used as predictor variables in prediction models.

The AMAS is a reliable and valid measure of acculturation. Studies have documented good to excellent internal consistency for the AMAS in college student and community samples (Zea et al., 2003; Zea, Reisen, Poppen, Echeverry, & Bianchi, 2004). The validity of the AMAS has been tested in multiple diverse samples including college and community samples of Latinos (Zea et al., 2003; Zea et al., 2004) and Russian-American adolescents (Birman, Trickett, & Buchanan, 2005). In the present study, excellent internal consistency was found for U.S.- and heritage-culture acculturation subscales (Cronbach’s alphas = .90 and .92, respectively).

Religiousness. The Religious Background and Behavior Questionnaire (RBB; Connors et al., 1996), a 13-item self-report measure, assessed participant religiousness. The RBB focuses on behavioral practices of religion and instructs participants to rate the frequency with which they have engaged in religious behaviors within the past year and throughout their lifetime. Religious participation within the last year (6 items) is rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 7 (More than once a day). Lifetime religious participation (6 items) is similarly reported on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 2 (Practiced behavior in the past and currently practices religious behavior). Additionally, participant-identified religiousness is scored on an ordinal scale ranging from 0 to 4 by selecting from categories that include Atheist, Agnostic, Unsure, Spiritual, and Religious. RBB items are summed to yield a total score that ranges from 0 to 58. The RBB has been found to be correlated with attendance at religious gatherings, existential seeking of meaning, and attendance and involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA; Connors et al., 1996), suggesting convergent validity with other measures of religiousness. In the present study, the RBB had acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .76).

The RBB was developed with a predominantly European-American sample, and thus many of the religious behaviors measured represent Judeo-Christian practices. Consequently, the RBB was altered in collaboration with representatives of the participating community organization to make survey items more appropriate for use with Muslim samples. All questions that referred directly to “God” were rephrased as “God/Allah.” Two items (within the last year and lifetime) that measured frequency of meditation were altered to ask how often participants engaged in “Extra voluntary worship (e.g., extra prayer, extra fasting, retreat, reflection, dhikr, hadhra)” because meditative practices are not considered distinct from routine Islamic prayer. Two items (within the last year and lifetime) that measured the frequency of participants’ direct experiences of God were eliminated because they were evaluated by representatives of participating organization as culturally inappropriate to individuals of Islamic faith. With the two items eliminated, the highest possible RBB score was 49.

Reasons for depression. The Reasons for Depression Questionnaire (RFD; Addis, Traux, & Jacobson, 1995), a 48-item self-report measure, assessed participants’ attributions of reasons for having experienced depression. Each item is presented with the stem “I am depressed because...” When used with nondepressed community samples, the RFD instructs participants to think of a time when they “were extremely sad and it lasted more than a little while.” Participants indicate the degree to which they believe each questionnaire item caused their depression. Items are endorsed on a Likert-scale that ranges from 1 (Definitely not a reason) to 4 (Definitely a reason).

Factor analysis of the RFD has found evidence for two higher-order factors that correspond to subscales that measure individually and interpersonally oriented reasons for depression (Individual Reasons for Depression and Interpersonal Reasons for Depression, respectively; Addis et al., 1995). Measure items related to existential problems and disillusionment, failure to fulfill self-expectations, individual personality characteristics, and physical health load onto the Individual Reasons for Depression subscale, whereas items related to interpersonal conflict, relationship problems, difficulty with intimacy, and problems experienced during childhood load onto the Interpersonal Reasons for Depression subscale. In the present study, Individual Reasons for Depression and Interpersonal Reasons for Depression subscales were employed as criterion variables in prediction models. The RFD has demonstrated good internal consistency among nonclinical samples with respect to the entire questionnaire (Cronbach’s alpha = .94) and subscales (Cronbach’s alpha from .76 to .86; Addis et al., 1995; Thwaites, Dagnan, Huey, & Addis, 2004). In the present study, both RFD subscales had excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .92 for both subscales).

Results

Preliminary Analyses and Descriptive Statistics

Examination of score distributions indicated that the AMAS subscales, RBB, and RFD subscales violated assumptions of univariate and multivariate normality. All distributions were subsequently corrected using linear transformations as recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2001). AMAS United States acculturation, heritage-culture acculturation, and RBB scores were corrected using reflected inverse, reflected logarithmic, and reflected square root linear transformations, respectively. Thus, for acculturation and religiousness scales, higher scores correspond to lower acculturation and lower religiousness. Individual and Interpersonal Reasons for Depression subscales were transformed using logarithmic and inverse linear transformations, respectively. All transformed variables met assumptions for normality. For ease of interpretation, all descriptive statistics and correlations presented are untransformed scores. All inferential statistics were calculated from transformed data.

Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for heritage-culture acculturation, U.S.-culture acculturation, religiousness, individual reasons for depression, and interpersonal reasons for depression. Participants indicated moderately high levels U.S.-culture acculturation and heritage-culture acculturation. Thus, participant acculturation scores suggest that the present sample, in general, endorsed a bicultural acculturative style. Participants’ mean religiousness score similarly indicated a high level of behavioral involvement in religious practices. Bivariate correlations are also presented in Table 1. Age was significantly related to education and household income such that older participants were more educated and had a greater household income.[1] Total household income was significantly, negatively correlated with Individual and Interpersonal Reasons for Depression subscales. Total household income was also significantly, positively correlated with U.S.-culture acculturation. Therefore, total household income was included as a covariate in hypothesis testing. Notably, U.S.-culture acculturation and heritage-culture acculturation subscales were not significantly correlated with each other, suggesting that among the present sample U.S.-culture acculturation and heritage-culture acculturation may be orthogonal constructs. Greater religiousness was significantly correlated with lower individually oriented reasons for depression. Greater heritage-culture acculturation was significantly correlated with lower interpersonally oriented reasons for depression.

Due to the large representation of males in the present sample (81.6%), independent samples t-tests were conducted to determine if significant gender differences existed between acculturation (both subscales), religiousness, and beliefs about depression (both subscales). Although there was a trend toward higher heritage-culture acculturation for men (M = 3.34, SD = 0.48) compared to women (M = 3.04, SD = 0.67), this finding was not statistically significant, t (74) = 1.93, p = .057. No significant gender differences were found for U.S.-culture acculturation, religiousness, individual reasons for depression, and interpersonal reasons for depression (p’s between .25 and .82).

Preliminary analyses were also conducted to test for differences between Pakistani and Palestinian participants’ demographic characteristics and acculturation, religiousness, and individually and interpersonally oriented reasons for depression scores. Independent samples t-tests were conducted to screen for differences between Pakistani and Palestinian groups’ age and number of years lived in the United States. No significant group differences were found with respect to Pakistani (M = 32.48, SD = 16.71) and Palestinian (M = 36.33, SD = 11.52) participants’ age (p = .24). However, the reported number of years living in the United States was significantly greater for Palestinian participants (M = 22.74, SD = 8.62) than for Pakistani participants (M = 14.08, SD = 12.39), t (73) = -3.52, p =.001. Chi-square tests of independence were conducted to identify whether there were differences between Pakistani and Palestinian groups’ generation level, marital status, and gender composition. Due to the small number of divorced participants, marital status was collapsed into a dichotomous married/unmarried category before conducting chi-square tests. No significant differences were found for Pakistani and Palestinian participants’ generation level or gender composition (p’s > .70). In contrast, there was a significant difference between groups such that significantly more Palestinian (n = 38) than Pakistani (n = 11) participants reported that they were married χ2 (1) = 6.82, p = .009. Lastly, independent samples t-test were also conducted to screen for significant differences between Pakistani and Palestinian groups with respect to heritage-culture acculturation, U.S.-culture acculturation, religiousness, individual reasons for depression, and interpersonal reasons for depression. No significant differences between Pakistani and Palestinian groups were found (p’s between .08 and .97).

Primary Analyses

To test the relationships among U.S.- culture and heritage-culture acculturation, religiousness, and individually and interpersonally oriented reasons for depression, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted. Due to the significant associations between total household income, U.S.-culture acculturation, individually oriented reasons for depression, and interpersonally oriented reasons for depression, total household income was entered as a covariate in the first step of each multiple regression. U.S.-culture and heritage-culture acculturation subscales were entered simultaneously in the second step of the regression to test the relationship of cultural adaptation processes to reasons for having experienced depression after covarying the influence of total household income. Lastly, religiousness was entered as the third step of hierarchical multiple regression analyses. Although research suggests that mental health outcomes are significantly associated with both acculturation and religiousness, prior findings have been limited in that they have only investigated their joint relationship by comparing the influence of acculturation to mental health between Muslims and non-Muslims (Awad, 2010; Amer & Hovey, 2007). Thus, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were employed instead of standard simultaneous entry in order to test the ability of religiousness to explain residual variance unaccounted for by the relationship of acculturation to reasons for having experienced depression. Power analysis for the full regression model was conducted using G*Power 3.1 software (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009). Assuming a medium effect size of 0.15, power was .73 for hierarchical multiple regression analysis conducted with N = 74 participants using 4 predictor variables.

Individual reasons for depression. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted as described above to determine the influence of total household income, AMAS acculturation subscales, and religiousness on the Individual Reasons for Depression subscale (see Table 2). The overall model was significant, F (4, 70) = 5.56, p = .001. Household income significantly predicted Individual Reasons for Depression subscale, t = -3.15, p = .002, such that higher household income was associated with lower reported individually oriented reasons for depression. Participants’ RBB score also significantly predicted Individual Reasons for Depression, t = 2.98, p = .004, above and beyond variance accounted for by total household income. Specifically, greater reported participation in activities associated with Muslim faith significantly predicted lower individually oriented reasons for having experience depression. Neither U.S.-culture acculturation nor heritage-culture acculturation significantly predicted individually oriented reasons for depression.

Interpersonal reasons for depression. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine the influence of total household income, AMAS acculturation subscales, and religiousness on the Interpersonal Reasons for Depression subscale (see Table 2). The overall model was significant, F (4, 70) = 5.05, p = .001. As with individual reasons for depression, total household income was a significant predictor of the Interpersonal Reasons for Depression subscale, t = 2.79, p = .007. Interestingly, total household income predicted interpersonally oriented reasons for depression such that greater household income was associated with participants having experienced more frequent interpersonal sources of depression. Acculturation subscales were entered in the second step and contributed unique variance above and beyond that accounted for by total household income. Lower heritage-culture acculturation significantly predicted greater interpersonally oriented reasons for having experienced depression, t = 2.33, p = .02. U.S.-culture acculturation failed to significantly predict interpersonal reasons for having experienced depression. Unexpectedly, RBB scores significantly, negatively predicted Interpersonal Reasons for Depression subscale scores, t = -2.08, p = .04, indicating that greater religiousness was associated with greater interpersonal reasons for having experienced depression. Religiousness contributed unique predictive variance above and beyond that accounted for total household income and heritage-culture acculturation.

Due to the significant relationship among heritage-culture acculturation and religiousness on interpersonally oriented reasons for depression, an interaction term was computed using the AMAS Heritage-Culture Acculturation subscale and RBB. Heritage-culture acculturation and religiousness were centered prior to computing the interaction term, as recommended by Aiken and West (1991). To test the ability for religiousness to moderate the relationship between heritage-culture acculturation and interpersonally oriented reasons for depression, hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted. The centered terms for heritage-culture acculturation and religiousness were entered in the first step of the regression, followed by the interaction of heritage-culture acculturation and religiousness. The overall regression model was significant, F (3, 72) = 3.32, p = .02. As with the previous analysis, lower heritage-culture acculturation was significantly related to interpersonally oriented reasons for depression, β = .26, SE = .13, t = 2.37, p = .02. Similarly, greater religiousness was associated with greater interpersonally oriented reasons for depression at the trend level of significance, β = -.21, SE = .02, t = -1.91, p = .06. The interaction term, however, did not significantly predict interpersonally oriented reasons for depression, suggesting that heritage-culture acculturation and religiousness constitute independent pathways relative to the prediction of interpersonal reasons attributions for having experienced depression. Due to the nonsignificant relationship between the interaction of heritage-culture acculturation and interpersonally oriented reasons for depression, no tests of simple slopes were conducted.

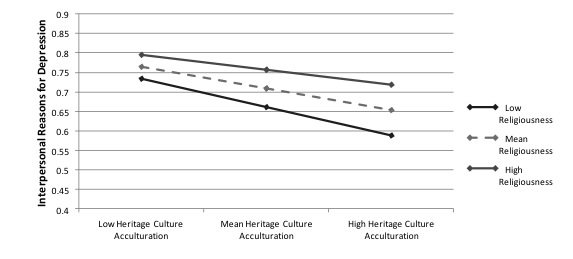

To further examine the joint influences of heritage-culture acculturation and religiousness on interpersonal reasons for depression, participants’ Heritage-Culture Acculturation subscale scores and RBB scores were categorized into high and low heritage-culture acculturation and religiousness, respectively. High heritage-culture acculturation and high religiousness scores were defined as those scores that were one standard deviation above their scale mean (Aiken & West, 1991). Similarly, low heritage-culture acculturation and low religiousness scores were those scores that were one standard deviation below their corresponding scale mean. Figure 1 presents a graph of the resultant slopes for the influence of heritage-culture acculturation and religiousness on interpersonal reasons for depression. Consistent with the results of the multiple regression analyses, independent main effects are evident. That is, high heritage-acculturation was significantly associated with lower self-reported interpersonal reasons for having experienced depression regardless of participant religiousness. Additionally, higher self-reported religiousness was associated with greater interpersonal reasons for having experienced depression regardless of degree of heritage-culture acculturation. Taken together with the nonsignificant interaction of the multiple regression analysis, these findings suggest that religiousness and heritage-culture acculturation have an additive influence on interpersonally oriented reasons for having experienced depression among Muslims.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship of acculturation and religiousness on beliefs about reasons for having experienced depression among a community sample of Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims. It was hypothesized that acculturation would predict reasons for having experienced depression, such that U.S.-culture acculturation would be significantly associated with greater individually oriented reasons for depression, and heritage-culture acculturation would be significant associated with lower interpersonally oriented reasons for depression. It was also hypothesized that greater religiousness would be significantly associated with lower individually and interpersonally oriented reasons for depression. The results partially supported these hypotheses. Although U.S.-culture acculturation was not associated with participants’ individually oriented reason for depression, greater religiousness significantly predicted lower individually oriented reasons for depression. Consistent with the study’s hypotheses, lower heritage-culture acculturation was significantly associated with greater interpersonally oriented reasons for depression; religiousness was also significantly associated with greater interpersonally oriented reasons for depression, with the variance accounted for by religiousness above and beyond the variance accounted for by heritage-culture acculturation. Surprisingly, and contrary to study hypotheses, greater religiousness significantly predicted greater self-reported interpersonally oriented causes of depression. The findings did not indicate that religiousness moderated the heritage-culture acculturation-interpersonal reasons for depression relationship, suggesting that acculturation and religiousness additively (but independently) influence interpersonal reasons for depression.

Overall, the results suggest that cultural adaptation processes and religiousness may play different roles in the types of attributions that Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims make relative to specific causes for depression. The finding that religiousness is not significantly correlated with acculturation at the bivariate level was unexpected given previous research that has found a significant relationship among religion, U.S.-culture acculturation, and heritage-culture acculturation (Awad, 2010). However, these previous findings are based on comparisons of self-identified religion among Arab Christian and Muslims, rather than religiousness. The present study, in contrast, examined self-reported religiousness among Muslims only, and as such suggests that, despite its importance as a cultural construct, religiousness may be separate and unrelated to acculturation.

The finding that acculturation was not associated with individually oriented reasons for depression suggests that adaptation to United States’ culture and retention of heritage culture characteristics are also unrelated to attributions for experiencing depression that reflect individual, internal characteristics and traits. Thus, Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims’ perception of depressive affect as stemming from internal characteristics, personal achievements, biological predispositions, or existential reasons was not influenced by changes in culturally based behaviors, thought processes, or values. Importantly, however, the finding that religiousness was significantly associated with lower individually oriented reasons for depression suggests that Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims perceive religious participation as protective for internal causes of depression and dysphoric affect. This finding is consistent with previous research that suggests that, among Muslim Americans, religiousness – but not acculturation – was significantly associated with mental health (Amer & Hovey, 2007). Religious coping process may provide a possible explanation of this relationship (e.g., Smith et al., 2003). In this context, religiousness may serve as a protective coping mechanism against stress associated with internal, dispositional characteristics that contribute to the development or exacerbation of depressive affect. For example, religiousness may reduce the level of internal, individually oriented reasons for experience depression by providing participants’ lives with personal meaning and purpose (Koenig & Larson, 2001). This interpretation is supported by previous findings that, during times of substantial personal turmoil and distress, the Muslim community, and Islamic faith and practices in particular, serve as significant and central emotional resources (Abu-Ras et al., 2008; Abudabbeh, 2005; Ghorbani et al., 2007; Nath, 2005; Noor, 2008).

A different pattern of results emerged for interpersonally oriented reasons for depression. Interpersonally oriented reasons for depression reflected content such as interpersonal conflict between friends, spouse, and family members. The present results suggest that loss of those behaviors, knowledge, and values associated with one’s cultural background may be related to elevated interpersonal conflict with other members of one’s cultural background, which in turn may be associated with elevated depressive affect. These results are noteworthy in that they suggest that it is the loss of behaviors, values, and characteristics associated with one’s heritage culture, rather than the acquisition of majority culture behaviors and characteristics, that is predictive of depression related to interpersonal conflict.

The unexpected finding that greater religiousness was significantly related to greater interpersonally oriented reasons for depression and the nonsignificant interaction suggests that religiousness and acculturation influence interpersonal reasons for depression in an additive manner. Although the present findings suggest that religiousness may be a protective factor against individually oriented reasons for depression, it is, regardless of acculturation level, associated with greater interpersonally oriented reasons for depression. One possible explanation for this main effect is that Muslims who report greater religiousness may also posses more conservative, traditional religious views. This, in turn, may be associated with greater interpersonal conflict among other Muslims who have less conservative, traditional religious views. Low heritage-culture acculturation appears to compound the influence of religiousness on interpersonally oriented attributions of reasons for having experienced depression. Specifically, the results suggest that lower culturally related behaviors, knowledge, and attitudes associated with one’s culture, in the context of high engagement in culturally relevant behavior such as religious participation, may be associated with greater perceived interpersonal conflict with other Muslims, which in turn contributes to depression.

Limitations

The current study possesses some weaknesses that deserve comment. First, participants were a community, convenience sample of Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims. Diagnostic information, symptom rates, and symptom severity were not collected from participants. The results may not generalize to Muslims who meet diagnostic criteria for depressive disorders, and should therefore be replicated using clinical samples. This study is further limited by the small number of female participants; it has long been recognized that rate of depression among females is twice that of males (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002) and studies have noted significant gender differences in depression among South Asian and Middle Eastern cultures (Bhui et al., 2004; El-Islam et al., 1988; Mirza & Jenkins, 2004; Upmany et al., 2000). With respect to the present study, preliminary analyses failed to find significant gender differences in acculturation, religiousness, and reasons for depression. These results, however, should be replicated using a larger female sample to further assess the degree to which the present findings generalize to female American Muslims.

Lastly, the study is limited by its cross-sectional design. Thus, causal relationships among variables cannot be determined. For example, it is possible that those Muslims who experience depression that they attribute to individual or interpersonal causes may be more likely to employ greater religious participation as a positive coping mechanism (Smith et al., 2003). Additional research is necessary to clarify the nature of the relationship between religiousness and depression among Muslims. Specifically, longitudinal designs are necessary to determine if religiousness is predictive of later depression, rather than depression predicting later religiousness.

Future directions

Longitudinal studies of acculturation remains a critical future direction for research. Acculturation is, by definition, a state of change (Berry, 2003). The present sample consisted largely of Pakistani and Palestinian immigrants who are adapting to cultural norms, values, and behaviors that in some cases may be quite distinct from their own. One would expect psychosocial functioning to change over time in accordance with acculturation. Additionally, cultural groups’ unique migratory experiences differentially impact the relationship between acculturation and psychosocial adjustment (Balls Organista et al., 2003). For example, the September 11 attacks and the United States’ military involvement in the Middle East and Afghanistan have made Muslim individuals acutely aware of others’ explicit and implicit prejudices (Abu-Ras et al., 2008). Perceived prejudice experienced during the acculturative process has been found to be predictive of psychosocial functioning (e.g., Rahman & Rollock, 2004), and evidence suggests that Muslims with higher U.S. acculturation perceive greater discrimination than Muslims with lower U.S. acculturation (Awad, 2010). Future research should therefore incorporate perceived prejudice in study design to assess the extent to which it moderates predictive relationships among acculturation and mental health.

The present study examined the degree to which acculturation and religiousness predicted attributions about reasons for having experienced depression in a community sample of Pakistani and Palestinian Muslims. A major finding was the identification of the differential influence of religiousness and acculturation on reasons for having experienced depression, dependent on whether the identified cause of depression was attributed to individual or interpersonal reasons. Individual reasons for depression were predicted by religiousness only, whereas heritage-culture acculturation and religiousness jointly predicted interpersonal reasons for depression. Future research should investigate these findings longitudinally to further clarify the influence acculturation, and religiousness have on Muslim mental health, and in the interest of developing culturally appropriate, effective interventions for the treatment of depression in Muslim populations.

Acknowledgement and contact information:

Some of these data were presented at the 2009 annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, August, 2009, in Toronto, Canada. The authors thank Ahmed Quereshi and Ziad Hamdan for their helpful feedback during the development of this research and for their assistance with data collection. The authors also wish to thank the participants.

Mark Driscoll is now at the Institute on Social Exclusion. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Mark W. Driscoll, Institute on Social Exclusion, Adler School for Professional Psychology, 17 North Dearborn Street, Chicago, IL 60602. Email: [email protected]

References

- Abu-Ras, W., Geith, A., & Cournos, F. (2008). The imam’s role in mental health promotion: A study at 22 mosques in New York City’s Muslim community. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 3, 155-176.

- Abu-Rayya, H. M., & Abu-Rayya, M. H. (2009). Acculturation, religious identity, and psychological well-being among Palestinians in Israel. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33, 325-331.

- Abudabbeh, N. (2005). Arab families: An overview. In M. McGoldrick, J. Giordano, & N. Garcia-Preto (Eds.), Ethnicity and family therapy (3rd ed., pp. 423-436). New York: Guilford Press.

- Addis, M. E., Traux, P., & Jacobson, N. S. (1995). Why do people think they are depressed: The Reasons for Depression Questionnaire. Psychotherapy, 32, 476-483.

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Al-Sabwah, M. N., & Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2006). Religiosity and death distress in Arabic college students. Death Studies, 30, 365-375.

- Al-Subaie, A. S., Marwa, M. K. H., Hawari, R. A., & Abdul-Rahim, F. (1997). Psychiatric emergencies in a university hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Mental Health, 25, 59-68.

- Ali, O. M., Milstein, G., & Marzuk, P. M. (2005). The imam’s role in meeting the counseling needs of Muslim communities in the United States. Psychiatric Services, 56, 202-205.

- Amer, M. M., & Hovey, J. D. (2007). Socio-demographic differences in acculturation and mental health for a sample of 2nd generation/early immigrant Arab Americans. Journal of Minority Mental Health, 9, 335-347.

- Awad, G.H. (2010). The impact of acculturation and religious identification on perceived discrimination for Arab/Middle Eastern Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 59-67.

- Balls Organista, P., Organista, K. C., & Kursasaki, K. (2003). The relationship between acculturation and ethnic minority mental health. In K. M. Chun, P. Balls Organista, & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 139-161). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Benish, S. G., Quintana, S. G., & Wampold, B. E. (2011). Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: A direct comparison meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 279-289.

- Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. Chun, P. Balls Organista, & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp.17-37). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bhui, K., Bhugra, D., Goldberg, D., Sauer, J., & Tylee, A. (2004). Assessing the prevalence of depression in Punjabi and English primary care attenders: The role of culture, physical illness and somatic symptoms. Transcultural Psychiatry, 41, 307-322.

- Birman, D., Trickett, E., & Buchanan, R. M. (2005). A tale of two cities: Replication of a study on the acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents from the former Soviet Union in a different community context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 83-101.

- Çirakoğlu, O. C., Kökdemir, D., & Demirutku, K. (2003). Lay theories of causes of and cures for depression in a Turkish university sample. Social Behavior and Personality, 31, 795-806.

- Connors, G. J., Tonigan, J. S., & Miller, W. R. (1996). Measure of religious background and behavior for use in behavior change research. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 10, 90-96.

- Crittenden, K. S., Fugita, S. S., Bae, H., Lamug, C. B., & Un, C. (1992). A cross-cultural study of self-report depressive symptoms among college students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 23, 163-178.

- El-Islam, M. F., Moussa, M. A. A., Malasi, T. H., & Mirza, I. A. (1988). Assessment of depression in Kuwait by principal component analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 14, 109-114.

- Fan, C. (1999). A comparison of attitudes toward mental illness and knowledge of mental health services between Australian and Asian students. Community Mental Health Journal, 35, 47-56.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149-1160.

- Furnham, A., Ota, H., Tatsuro, H., & Koyasu, M. (2000). Beliefs about overcoming psychological problems among British and Japanese Students. Journal of Social Psychology, 140, 63-74.

- Ghorbani, N., Watson, P. J., & Rostami, R. (2007). Relationship of self-reported mysticism with depression and anxiety in Iranian Muslims. Psychological Reports, 100, 451-454.

- Gureje, O., Lasebikan, V. O., Ephraim-Oluwanuga, O., Olley, B. O., & Kola, L. (2005). Community study of knowledge of and attitude to mental illness in Nigeria. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 436-441.

- Haghighatgou, H., & Peterson, C. (1995). Coping and depressive symptoms among Iranian students. Journal of Social Psychology, 135, 175-180.

- Hamdi, E., Amin, Y., & Abou-Saleh, M. T. (1997). Problems in validating endogenous depression in the Arab culture by contemporary diagnostic criteria. Journal of Affective Disorders, 44, 131-143.

- Hamid, H., Abu-Hijleh, N. S., Sharif, S. L., Raqab, M. Z., Mas'ad, D., & Abbas, A. (2004). A primary care study of the correlates of depressive symptoms among Jordanian women. Transcultural Psychiatry, 41, 487-496.

- Hugo, C. J., Boshoff, D. E. L., Traut, A., Zungu-Dirwayi, N.,& Stein, D. J. (2003). Community attitudes toward and knowledge of mental illness in South Africa. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38, 715-719.

- Hwang, W. C., & Ting, J. Y. (2008). Disaggregating the effects of acculturation and acculturative stress on the mental health of Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 147-154.

- Jibeen, T. (2011). Moderators of acculturative stress in Pakistani immigrants: The role of personal and social resources. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 523-533.

- Kim, B. S. K., & Abreu, J. M. (2001). Acculturation measurement: Theory, current instruments, and future directions. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (2nd ed., pp. 394-424).

- Koenig, H. G., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Religion and mental health: Evidence for an association. International Review of Psychiatry, 13, 67-78.

- Kuiper, N. A., & Cole, J. D. (1983). Knowledge about depression: Effects of depression and vulnerability levels on self and other perceptions. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 15, 142-149.

- Kumar, A., & Nevid, J. S. (2010). Acculturation, enculturation, and perceptions of mental disorders in Asian Indian immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 274-283.

- Miller, A. M., Sorokin, O., Wang, E., Feetham, S., Choi, M., & Wilbur, J. (2006). Acculturation, social alienation, and depressed mood in midlife women from the former Soviet Union. Research in Nursing & Health, 29, 134-146.

- Mirza, I., & Jenkins, R. (2004). Risk factors, prevalence, and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders in Pakistan: Systematic review. British Medical Journal, 328, 794-798.

- Moradi, B., & Risco, C. (2006). Perceived discrimination experiences and mental health of Latina/o American persons. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 411-421.

- Moyerman, D. R., & Forman, B. D. (1992). Acculturation and adjustment: A meta-analytic study. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 14, 163-200.

- Nath, S. (2005). Pakistani families. In M. McGoldrick, J. Giordano, & N. Garcia-Preto (Eds.), Ethnicity and Family Therapy (pp. 407-420).

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2002). Gender differences in depression. In I. H. Gotlib, & C. L. Hammen (Eds.), Handbook of depression (1st ed., pp. 492-509). New York: Guilford Press.

- Noor, N. M. (2008). Work and women’s well-being: Religion and age as moderators. Journal of Religion and Health, 47, 476-490.

- Ogbu, J. U. (1981). Origins of human competence: A cultural-ecological perspective. Child Development, 52, 413-429.

- Rahman, O., & Rollock, D. (2004). Acculturation, competence, and mental health among South Asian students in the United States. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 32, 130-142.

- Rogler, L. H., Cortes, D. H., & Malgady, R. G. (1991). Acculturation and mental health status among Hispanics: Convergence and new directions for research. American Psychologist, 46, 585-597.

- Sayed, M. A. (2003). Conceptualization of mental illness within Arab cultures: Meeting challenges in cross-cultural settings. Social Behavior and Personality, 31, 333-342.

- Smith, T. B., McCullough, M. E., & Poll, J. (2003). Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 614-636.

- Stephenson, M. (2000). Development and validation of the Stephenson Multigroup Acculturation Scale (SMAS). Psychological Assessment, 12, 77-88.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2006). Using multivariate statistics, 5th edition. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Thwaites, R., Dagnan, D., Huey, D., & Addis, M. E. (2004). The Reasons for Depression Questionnaire (RFD): UK standardization for clinical and non-clinical populations. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 77, 363-374.

- Thoman, L.V., & Surís, A. (2004). Acculturation and acculturative stress as predictors of psychological distress and quality-of-life functioning in Hispanic psychiatric patients. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 26, 293-311.

- Tsai, J. L., & Chentosova-Dutton, Y. (2002). Understanding depression across cultures. In I. H. Gotlib, & C. L. Hammen (Eds.), Handbook of depression (pp. 467-491). New York: Guilford Press.

- Upmanyu, V. V., Upmanyu, S., & Lester, D. (2000). Depressive symptoms among U.S. and Indian college students: The effects of gender and gender role. Journal of Social Psychology, 140, 669-671.

- Vasegh, S., & Mohammadi, M. (2007). Religiosity, anxiety, and depression among a sample of Iranian medical students. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 37, 213-227.

- Yang, F., & Ebaugh, H. R. (2001). Transformations in new immigrant religions and their global implications. American Sociological Review, 66, 269-288.

- Yen, S., Robins, C. J., & Lin, N. (2000). A cross-cultural comparison of depressive symptom manifestation: China and the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 993-999.

- Zane, N., & Mak, W. (2003). Major approaches to the measurement of acculturation among ethnic minority populations: A content analysis and an alternative empirical strategy. In K. M. Chun, P. Balls Organista, & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 39-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Zea, M. C., Asner-Self, K. K., Birman, D., & Buki, L. P. (2003). The Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale: Empirical validation with two Latino/Latina samples. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9, 107-126.

- Zea, M. C., Reisen, C. A., Poppen, P. J., Echeverry, J. J., & Bianchi, F. T. (2004). Disclosure of HIV-positive status to Latino gay men’s social networks. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33, 107-116.

- Zinnbauer, B. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2005). Religiousness and spirituality. In R. F. Paloutzian, & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 21-42). New York: Guilford Press.

Notes

The distribution of participants’ age was bimodal. Thus, to investigate possible differences among variables based on age, participants were categorized into 18 – 35 years old and 36 and older groups using a median split. Group comparisons with independent samples t-tests produced results identical to bivariate correlations. Young and old groups did not differ with regard to acculturation, religiousness, or reasons for experiencing depression.