Environmental and Structural Inequalities in Greater Accra

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Ever since the United Nations declared the International Decade on Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation in the 1980s, water and sanitation issues have remained high on the policy agenda of multilateral and bilateral agencies, national governments, and civil society organizations in developing countries. The policy interventions are aimed at enhancing access to water and sanitation facilities to promote the quality of environmental health for the most environmentally deprived communities in low-income cities, towns, and rural settlements all over Africa and much of the developing world. More recent targets have been set for reducing the share of the world’s population without adequate water and sanitation within the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Yet it is not quite clear what these targets and the indicators that have been set at the global level mean to local people in deprived communities in Africa’s cities.

This notwithstanding, it is thus far impossible to estimate with any precision the proportion of urban dwellers in Africa who live in poor housing with inadequate provision of water, sanitation, solid-waste disposal, and other basic housing and environmental services. But the overall picture available from limited data remains dismal. Conditions have been worsened by decades of structural adjustment in which access to basic services has been highly constrained by inadequate funding and cost-recovery measures, without a complementary expansion of services. This has placed a heavy burden on the poor, exacerbating their poverty.

While there has been an improved understanding of the nature and pattern of health risks associated with water- and sanitation-related deficiencies and the externalities inherent in many related environmental problems in previous decades, there is no communality of such shared knowledge among stakeholders concerned with water and sanitation provision in low-income areas. The knowledge gaps can be small or large between those using Western scientific standards and indicators and those using local community insights arising from daily life struggles in deprived communities facing multiple afflictions and risks. The perception of risks is not necessarily the same for the various stakeholders concerned with water and sanitation issues in low-income communities.

For policy interventions to have a long-term prospect for success, it is important that local knowledge is incorporated into any interventions on the water and sanitation question. Subjective indicators based on citizens’ perception of risk may hold the key to successful intervention in the provision of services.

This article presents data on the intra-urban differentials in accessing environmental services and the links between service provision and health in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA). It also compares the prioritization of environmental health-related risks by experts on a citywide scale and the local perception of risks at the community level using illustrative examples from five low-income communities in the areas of water and sanitation. The divergence in risk perception is notable and may have something to do with the strong links between hygiene and behavioral variables to health outcomes with regard to water and sanitation. This results from the lack of knowledge among the urban poor about the crucial importance of hygiene to health.

City Context

GAMA, which serves as both Ghana’s national capital and major industrial hub, includes the Accra Metropolitan Area (AMA), Tema Municipal Area, and Ga District. These three urbanized administrative areas have grown into a major urban agglomeration, not only in a physical sense but also economically and functionally, even though they continue to exist as separate administrative units. This greater metropolitan region, which had a combined population of 1.3 million in 1984, now stands at over 2.7 million people, according to Ghana’s 2000 Population and Housing Census. The estimated population for 2005 was 3.2 million, which is projected to increase to 4 million by 2010. The citizens of GAMA face pressing needs for water and sanitation and other household environmental services in all but a few privileged areas containing 10–30 percent of the metropolitan population.

The rapid population growth and physical expansion of GAMA have been occurring in an uncertain economic environment characterized by nearly a decade of economic decline in the mid-1970s and early 1980s that was followed by nearly two decades of structural adjustment. While reversing the economic decline, the era of structural adjustment has thus far failed to restore economic welfare to its precrisis levels. A large number of households within the metropolis are living in substandard housing and overcrowded conditions without the resources for decent shelter and access to adequate water- and sanitation-related services.

As a result, GAMA, like the rest of the country’s urban areas, is in the first stage of an urban environmental transition where most of the environmental problems occur close to home. These include inadequate access to potable water, sanitation facilities, and solid-waste disposal facilities, as well as smoky kitchens from the use of biomass fuels and insect infestation among others. These hazards directly threaten the health of citizens arising from the life and death immediacy of malaria, respiratory illness, diarrhea, and other infectious and parasitic diseases.

Accessing Services

Statistics summarizing environmental conditions are presented for five wealth groups of roughly equal size, that is, each covering about 20 percent of the sample households. These wealth categories were constructed on the basis of an index computed from household ownership of consumer durables. Gordon McGranahan and I (2007) wrote, “While this grouping is intended to be relevant to discussions on class and poverty, there is no suggestion that the groups constitute classes, or that poverty is defined by the absence of consumer durables.”

Although average urban incomes in GAMA are higher than those in other urban centers in Ghana and although most poor people live in rural areas, poverty in GAMA is widespread by international standards. More recent evidence from national statistics shows that it is increasing. For example, poverty in the metropolis more than doubled between 1988 and 1992, up from 9 percent to 23 percent, while the depth of poverty increased from 2 percent to 6 percent. This is based on arbitrary poverty lines set by the World Bank. More recent data from the Ghana Statistical Service suggests that the metropolis has, however, made significant gains in poverty reduction between 1991/92 and 1998/99. There is a general tendency to underestimate urban poverty because the high cost of living in the city is often not factored into the determination of poverty levels and because the existence of the poor is not recognized. They live in the shadow of the city, and their conditions are blurred by average statistics and by the illegality of their existence.

There are widespread intra-urban differentials in accessing environmental services or amenities. Some of the most relevant intra-urban inequalities in this regard include potable water and sanitation and, to a lesser extent, sullage and solid-waste disposal facilities. The importance of an adequate supply of potable water and proper sanitation practices is well established, and there is a close relationship between wealth and access to potable water and sanitary services within GAMA. Most households surveyed rely on the piped system for their water supply, but the distribution is highly uneven and service delivery is erratic throughout the system, especially in low-income areas and new developments in the peri-urban zone.

While most wealthy households have in-house piping, typically connected to overhead storage containers, the poorest and most deprived households rely mostly on informal water vendors, communal standpipes, and other less efficient water-supply sources. These require in-house storage of water in drums and other containers that easily become contaminated, as shown by the results of the physical tests of water quality. In an urban survey conducted by myself and others in 1993, about 35 percent of households had access to in-house piped water, 24 percent used private standpipes, and another 8 percent relied on communal standpipes for drinking water. As much as 28 percent of households depended on informal water vendors for their daily water supply. Perhaps the most disadvantaged households were the 4 percent of GAMA residents whose main source of water supply was from open waterways, rainwater collection, wells, and other private sources.

Sanitation management also has very critical health implications. As with access to water supply, inequalities in access to toilet facilities are also related to household wealth. Pit latrines are common in low-income households, while flush toilets (both sewered and septic) dominate higher-wealth groups. About 36 percent of households in GAMA have access to flush toilets; 41 percent use pit latrines, some of which are Kumasi Ventilated Pit Latrines; 20 percent use bucket or pan latrines; and 4 percent have no access to toilet facilities.

Inadequate sullage and solid-waste disposal is a common feature in the metropolitan area. These inadequacies provide the ecological niches for the breeding of vectors, parasites, and the transmission of disease. About 46 percent of all household sullage is discharged through open separate drains, with yard and street dumping accounting for 25 and 13 percent respectively. Only 3 percent of all households dispose of their sullage through the sewer system or septic tanks, with another 7 percent served by closed separate drains. Most of the limited cases of best practices with regard to sullage disposal occur in wealthy households.

In terms of visibility, garbage or solid-waste management remains one of the most intractable problems within GAMA, although its health implications may not be as serious as those of the water-sanitation complex. Residential domestic waste is estimated to form a greater proportion of all sources of solid wastes produced in Ghanaian urban settlements. Currently, the Waste Management Department of AMA, for example, is capable of collecting only 60 percent of the over 900 tons of refuse and 300 tons of night soil generated per diem. The position is marginally better for Tema District but far worse in Ga District.

Health Implications for Urban Children

A large number of environmental risk factors implicated in diarrhea prevalence in children relate to access to environmental services such as adequate water supply and sanitation facilities (see table 1a).

Table 1a. Access to Environmental Services and Children’s Diarrhea Prevalance (%)| Category | Size of Subsample | Two-week Prevalence of Diarrhea (%) |

| A. Principal Drinking Water Source | ||

| In-house piping | 162 | 6.8 |

| Private standpipe | 139 | 10.1 |

| Communal standpipe | 50 | 42.0 |

| Vendor | 165 | 13.9 |

| Other | 21 | 14.3 |

| B. Number of Taps in Home | ||

| None | 375 | 16.3 |

| One | 53 | 5.7 |

| More than one | 108 | 7.4 |

| C. How Water is Carried Home | ||

| Hand carried | 85 | 24.7 |

| Head carried | 170 | 17.7 |

| Other (e.g., piped) | 280 | 7.5 |

| D. Location of Water Source | ||

| In-house compound | 266 | 7.1 |

| Out of house | 270 | 19.6 |

| E. Access to Toilet | ||

| Flush | 164 | 6.7 |

| Pit latrine | 241 | 17.0 |

| Pan latrine | 113 | 15.9 |

| Other/none | 19 | 10.5 |

| F. Pay for Use of Toilet | ||

| No | 159 | 6.9 |

| Yes | 344 | 16.9 |

Risk perception and hygiene behavior are additional aspects of the social context that affect exposure to risks associated with inadequate access to clean water and sanitation facilities. Given the widespread practice of unhygienic water handling and storage in deprived low-income areas, it is not enough to focus on bringing “water to the tap”; what is happening “between the tap and the mouth” is also critical in determining health outcomes. For example, the use of communal dip cups also encourages drinking-water contamination.

Table 1b summarizes the prevalence of childhood diarrhea among households with different water and sanitation behavior, such as closure of water-storage containers, outdoor defecation of neighborhood children, hand-washing practices, covering of prepared food, and cleaning of toilets. Ongoing downstream studies tend to suggest that these gaps in service access (see table 1a) and hygiene behavior have remained largely unchanged or have grown even worse in some respects.

Table 1b. Hygiene Behavior and Children’s Diarrheal Prevalence (%)| Category | Size of Subsample | Two-week Prevalence of Diarrhea (%) |

| A. Water Storage Container Closure | ||

| No container | 17 | 0.0 |

| Open | 94 | 27.7 |

| Closed | 426 | 10.8 |

| B. Neighborhood Children Defecate Outdoors | ||

| No | 386 | 8.8 |

| Yes | 145 | 26.2 |

| C. Hand Washing Prior to Food Preparation | ||

| Not mentioned | 132 | 22.0 |

| Mentioned | 394 | 10.7 |

| D. Uncovered Prepared Food Observed | ||

| No | 465 | 11.8 |

| Yes | 72 | 23.6 |

| E. Clean Toilet | ||

| No | 209 | 19.6 |

| Yes | 311 | 9.3 |

Priority Setting

Based on descriptive evidence of the environmental health conditions gained from the above research, a risk-assessment ranking methodology was developed to allow for a rapid assessment of conditions for the purpose of strategic planning within GAMA. The risk assessment integrates data on water, sanitation, hygiene, solid waste, sullage/drainage, pests and pesticide use, food contamination, household air pollution, and crowding. This was developed using the Delphi technique. Two hundred points were allocated in a weighted fashion across these nine environmental problem areas, which were identified in an earlier study, according to their health implications. This process allows an integrated scoring and mapping of environmental health conditions/burdens across these problem areas for each residential area. Special attention was given to the links between environment and health with a focus on children and women as key environmental managers. The rapid-assessment methodology allows routine monitoring of the environmental health situation of different neighborhoods as a tool for environment and health planning and management. This approach is based on a positivist epistemological position, which, according to B. Obrist, P. van Eeuwijk, and M. G. Weiss (2003), “considers risks as objective facts that have a measurable impact on human health.” It directs attention to risk factors that, in keeping with our scientific knowledge, determine health outcomes.

Experts ranked water and sanitation as the top two environmental problems needing priority attention based on their importance to health. These were followed by pests, sullage/drainage, food contamination, hygiene, solid waste, housing, and air pollution in descending order of importance. Figure 1 shows the distribution of water-related risks in GAMA. The higher the percentage score, the more severe the environmental risks are to health in the particular community. These are expressed as quintiles of environmental health burdens: 1–20 percent, 21–40 percent, 41–60 percent, 61–80 percent, and 81–100 percent. The total scores in the rapid assessment for each residential area were expressed as percentages of the maximum scores assigned to the problem areas in our basic model and provided the input for determining the quintile to which the residential area is situated in relation to the problem in question. As evident in this figure, most low-income areas still face severe water-related risks, since most lie within the fourth and fifth quintiles of environmental burdens that arise from inadequate water and sanitation service provision.

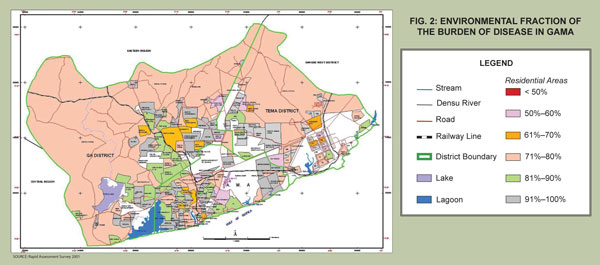

Figure 2 shows the area-based variations in the environmental fraction of the burden of disease, calculated by expressing the total number of environment-related diseases listed from data derived from local pharmacies/expert judgment, local clinic records, and focus-group discussions as a percentage of the total number of listed diseases in the residential area. The percentage score is what is termed the environmental fraction of the burden of disease. The first point to make is that the environmental fraction looms large within the entire metropolitan region, affecting both wealthy and poor alike. Nowhere in GAMA is the environmental fraction of the burden of disease below 50 percent (see fig. 2). This is consistent with data from the Ministry of Health indicating a preponderance of environment-related diseases in the metropolis.

The prioritization of water- and sanitation-related risks that one would expect from this expert judgment of health risk within the metropolitan region, however, is not replicated when community or participatory approaches are used to set priorities.

Risk Perception

Proponents of participatory and anthropological perspectives-to-risk perception give priority to community concerns, not academic scientific frameworks, pointing out that researchers participate in different social worlds from those of the urban poor and, therefore, may have different values and priorities from those who often face multiple deprivations. As a result, setting priorities, devising technical solutions, and standardizing intervention packages cannot on their own adequately address the multifarious problems of poor communities in African cities. The best technical solutions will not be effective if they fail to reach or are not accepted by the poor. From the perspective of the anthropology of health and illness, according to Obrist et al. (2003), “Priorities for research are questions of how people who actually live in the urban neighbourhoods we study experience, interpret, and respond to those aspects of city life that they consider being problematic.”

The results of further study show different priorities for water and sanitation issues in some of the high-risk communities in GAMA, priorities that sometimes do not coincide with those of experts. The illustrative examples are from Jamestown, Sukura, Sabon Zongo, Sodom and Gomorrah, and Pig Farm. In these low-income communities men, women, and youth in focus-group discussions were asked to rank their community’s top-five priority environmental problems. The mean rank for the three groups was used to determine each community’s collective prioritization of problems.

Even though these communities had high environmental burdens with regard to water-related risk, such as high diarrheal prevalence, in most cases other problems were given higher priority in their daily life experiences that may have no direct relationship to health outcomes. Water, in three cases out of five, was not listed within the top-five priority environmental problems. The communities for which water did not feature among the top-five problems were Sukura, Sabon Zongo, and Pig Farm. It was ranked the third most important environmental problem in Sodom and Gomorrah, a squatter settlement, and fifth in Jamestown. All of the communities ranked sanitation as their number-one priority problem, which had been ranked second after water in the environmental priorities of the scientists or experts in GAMA.

Within communities, priorities also varied by sex and age. In Sukura the first two priorities for men were crowding/housing and unemployment, with sanitation in third place and water in seventh. Women’s first two priorities were sanitation and solid waste, with water ranked twelfth. The first two priorities for youth were similar to those for women, while youth ranked water tenth. In Sabon Zongo all three groups placed sanitation as the most important priority. Solid-waste problems were placed second for women and youth, while men considered sullage/drainage as their second most important problem. Similar observations could be made for other groups.

Sanitation was ranked first because of the undue hardship felt in terms of crowding, cost, lack of privacy, and the nuisance of smell associated with inadequate access to sanitation services, and less because of health. Most low-income dwellers were quite satisfied with water supply as long as water could be purchased by the bucket from an informal water vendor next door. Most low-income households could not fathom the health implications of poor water handling and therefore gave water low priority in the constellation of multiple afflictions in their communities.

This would seem to suggest a shift away from a narrow concern with risk factors to concerns with afflictions. It is therefore always important to contextualize problems and to understand that the main priorities of the poor may not always coincide with our concept of the germ theory of disease. Issues of behavior change at the public/community level, and the private/domestic level should be given equal consideration along with water and sanitation infrastructure provision if the poor are to maximize the health benefits of interventions.

Conclusion

The evidence from this analysis, which is based on extensive work undertaken by our study team, suggests that no progress has been made in addressing problems of service provision as the population has grown. The physical expansion of the metropolitan region through urban sprawl has occurred without the complementary expansion of services with regard to water and sanitation and, indeed, most other services.

The earlier State of Environmental Health Report emphasized the focus on urban primary health care and intersectoral coordination in planning the delivery of services and provision of housing. The current analysis suggests that community education and mobilization may also be required if water and sanitation problems are to be prioritized out of the numerous livelihood problems that low-income dwellers are facing, and they may be a useful point of entry in attempts to address the many other concerns in a holistic manner. As D. Satterthwaite (2003) stated, “The challenge for international agencies in meeting the MDGs is as much to do with developing ways to support bottom-up processes accountable to low-income groups . . . as it is to do with total financial flows.”

For far too often many project interventions in water and sanitation and the infrastructure sector in general have been undertaken on behalf of the poor without their engagement as the primary stakeholders. This often leads to failure or lack of sustainability of such infrastructure projects and limits their health benefits. A classic example is the Accra Waste Project, which was implemented by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development as an Aid for Trade project without appropriate involvement of stakeholders in the affected communities.

It is the hope that people living in deprived communities will be actively engaged in any interventions that seek to provide services so that they can play a part in the identification and prioritization of services and technological options that are appropriate to ensure sustainability. In most cases, it will also entail some community sensitization and education programs that raise awareness as to the need for behavioral change for better health.

Jacob Songsore is a Professor of Geography at the University of Ghana with specialization in Urban Studies and Regional Development Planning. He was a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan during the 2007–2008 academic year.

This article is based on a presentation to the Danish Research Network for Environment and Development (ReNED) at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, in August 2006.

References

Obrist, B., P. van Eeuwijk, and Michael G. Weiss. 2003. Health anthropology and urban health research. Anthropology and Medicine 10 (3): 267–274.

Satterthwaite, David. 2003. The millennium development goals and local processes: A summary. In The millennium development goals and local processes: Hitting the target or missing the point. ed. David Satterthwaite. London: IIED.

Songsore, Jacob and Gordon McGranahan. 1993. Environment, wealth and health: Towards an analysis of intra-urban differentials within the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana.

Songsore, Jacob and Gordon McGranahan. 2007. Poverty and the environmental health agenda in a low-income city: The case of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA), Ghana. In Marcotullio and Gordon McGranahan. London: Earthscan.

———. 1998. The political economy of household environmental management: Gender, environment and epidemiology in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area, World Development,

———. 2000. Structural adjustment, the urban poor and environmental management in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA)-Ghana, Bulletin of the Ghana Geographical

Songsore, Jacob, J. S. Nabila, Y. Yangyuoru, E. Amoah, E.K. Bosque-Hamilton, K.K. Etsibah, J. Gustafsson, and G. Jacks. 2005. State of environmental health report of the Greater Accra

Songsore, Jacob and Carolyn Stephens. 2008. The Accra waste project: From urban poverty and health to aid and trade. (Special Edition) Bulletin of the Ghana Geographical Association, 3