South African Universities in the Tumult of Change

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The world of knowledge production is lopsided, with its center of gravity resting somewhere in the mid-North Atlantic. Trends in the humanities and basic sciences that catch hold in the global north often imprint themselves in knowledge systems elsewhere. While robust knowledge systems in parts of the global south do exist, this substantial region of the planet has until recently suffered from lack of capacity. Development today within the South African higher educational sector remains uneven, with certain universities sharing modern facilities and top researchers while others limp from the past into the present. It has been said that uneven development is a fault that generally pertains to the global south, with its massive differences in wealth among citizens, access to resources (water, power, education), and its profoundly unequal regional economies. Half an hour outside a world-class South African city one may find flimsy shacks built on sand, cooking on paraffin stoves, and unregulated informal economies wrought with insecurity. Such inequality in development also pertains to universities. Where genuine originality has been generated in the south (e.g., in engineering, literary writing, physical anthropology), it has been all too often consigned to the category of quaint or marginal in Europe and the United States. Scholarship, writing, and research from the global south have until recently inadequately circulated in publishing venues read widely in the north. A lively production of knowledge was often restricted to the southern locale in question. No wonder that the “university of the south” experienced itself as—and in fact was—globally peripheral. These universities sought their legitimization in the global north and were dwarfed in their abilities to shape independent programs of knowledge production. The heydays of sub-Saharan African independence, beginning with Ghana in 1957, were characterized by new visions, new imaginations of Africa in the world, and the reshaping of relationships between new African nations and their colonial rulers. Charismatic, visionary leaders like Nkrumah, Nyerere, and others held lofty ideals for the African university—especially their role in building new nations from fragmented ones. This gave rise to discourses of transformation and new imaginations—the shaping of a new place for Africa in the world. The university was to be the place where postcolonial vision translated into the making of new knowledge, and a new generation would be educated to steer its course through the tumult of change.

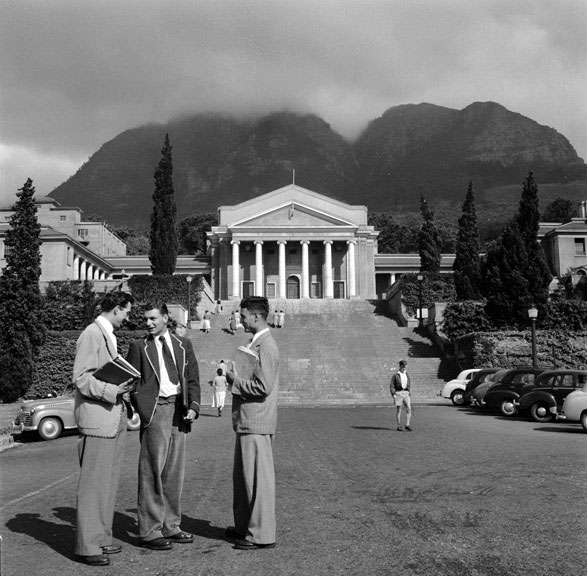

SOUTH AFRICA—Transformational policy in the 1990s proved to be highly successful in diversifying student populations in South African universities. Above, students at the University of Cape Town mingle in between classes. TED HANSS

Impediments to Knowledge Production

Shortly afterward, as a state of crisis set in nation by nation, African universities began to enter their own crises of chronic underfunding, which were consolidated by the structural adjustment programs forced on African nations by the World Bank. During this time, more instrumentalist notions of the university in Africa began to take hold—the advent of the “development university.” Recently the World Bank and UNESCO have established a series of substantial interventions with governments in Africa about the importance of large-scale investments in higher education, the larger social purpose being to integrate the insecure state economies of such states into the larger global economy. Similarly, one sees substantial investment in higher education by various development aid agencies such as the UK’s Department for International Development, Sweden’s SIDA-SAREC, the Ford Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation, and others.

Many South African universities have compounded their dependency through legacies of Eurocentrism, whereby settler gains status and authority over native populations and over time retains “non-native” identity by aping the European, acting “more British than British.” The liberal South African university between the conclusion of the Boer War in 1901 and the introduction of Apartheid in 1948 (the moment of the South African colony) formulated itself on a diet of Dickens, Trollope, and Shakespeare. Eurocentrism is dependency since it waits for scholarship and style from the mid-Atlantic center and immediately tries it on to insure the student becomes as “European” as possible. This formulation of university curriculum and scholarship consigned the South African university to the status of “outpost.” It is a template that the post-Apartheid moment directly assaulted, with the glorious result of skepticism: it is no longer known exactly what is the property of whom, what Europe is in Africa, what it is to be African, or to live in Africa. This training in uncertainty was perfect for a moment of change. But it was also accompanied by a fierce countermovement away from Eurocentrism toward equally radical closed-mindedness toward “the west” in the name of Afrocentric ideas of heritage. It began in the first generation of African leaders with their inward-looking adulation of the indigenous and the past, which was by that first generation of Africanist state presidents mythologized as a heritage better than anything learned from abroad. And it settled in universities, including the South African post-Apartheid university.

These three impediments—lack of capacity, exclusion from the global system of knowledge production, and vestiges of a combination of Eurocentrism and Afrocentric rejection—remain in place today in the university of the south, specifically in the South African university. But these obstacles are losing their hold. Ours is a critical moment for enhanced partnerships between South African and American universities as they change in all three respects. The global system is opening up substantially, in significant part due to the Internet and related new technologies, which allow instant access and communication between globally separated partners, and enable the formation of collaborative research groups that may include southern partners as equal players from the outset. These same technologies instantly build capacity, so long as sufficient infrastructure is in place to allow them to operate successfully. This is also true for publication, especially with online journals, which libraries (hobbled by poor exchange rates and lack of funds) need not purchase but can access online. This sadly continues to exclude many African countries that lack basic IT infrastructure: it does not exclude South Africa. The capacity of South African universities is being built by numerous players, recently by a consortium of American foundations that has joined European partners. And the Eurocentric/Afrocentric formulations of knowledge are being slowly overcome by the South African university: unique in its colonial, then Apartheid history. That history has left South African universities with basic faults, but it has also blessed them with unique gifts. These make South African universities admirable partners for American universities today. In what follows, we want to explain why. We shall do so, by turning to history.

An Architecture of Universities

The University of Cape Town (UCT) was formed in the nineteenth century as a place for training civil servants for English colonial management. This was the genesis of universities in the colonies. In South Africa an industrial base emerged in consort with a local industrial class—built by a colonial settler community and influx of new immigrants. And so the University of Witwatersrand (Wits) was formed in the early twentieth century by Scottish missionaries in the name of Matthew Arnold and Queen Victoria—liberalism and uplift, built in part by the gold and diamond magnates who wanted new engineering for their mines. In 1875 the city of Johannesburg hardly existed; by 1905 it had risen 15 stories toward the sky and descended 8,000 feet into the earth, where the gold was extracted in mines surrounding the city—with migrant labor drawn from all corners of rural South Africa and from as far afield as Nyasaland (now Malawi). With the rise of the city came immigration: Jews from Lithuania and Britain, Germans, Italians, Russians, Irish, and the Scottish who founded this liberal university.

Whites-only University of Cape Town campus (with Jameson Memorial Hall and Table Mountain in the background), circa 1955. EVANS/THREE LIONS/GETTY IMAGES

At the time of World War II, when the South African colony (formed at the end of the Boer War as a liberal/segregationist state) was still in place, Wits was ranked in the top 50 universities around the world. This was in part because it was flooded with the same generation of intellectuals and scientists fleeing Nazi Europe as Columbia, Princeton, and Michigan. The Apartheid state restricted immigration to reserve jobs for their own clan (Afrikaners) who had been disenfranchised by the English during the Boer War. And so Wits fell into some decline, which was hastened when the cultural boycotts—part of a large program of resistance against Apartheid—came into being; scholarship was bottlenecked there. The system-wide impact of the academic boycott was felt most acutely in the humanities and social sciences.

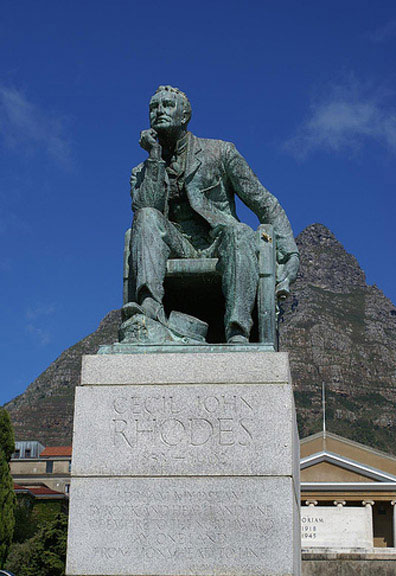

The University of Natal (the third major English university) was founded in 1910 in the provincial capital of Pietermaritzburg, and in the 1930s expanded to Durban as Howard College, built by a grieving parent to honor his son’s death in the war to end all wars. This law college was placed at the highest point on the highest hill directly overlooking the Durban port; it quickly acquired a statue of King George V on horseback surveying his dominion. George V had as its mirror and companion the statue of Cecil John Rhodes, erected above the University of Cape Town at the highest point on Table Mountain where it is possible to build, facing directly north, surveying the country between “Cape and Cairo” that in his vision of English lordship would be the King’s. University was a beacon of this colonial vision and remained so during the Apartheid period, but with a difference.

Cecil John Rhodes facing directly north, surveying the country between “Cape and Cairo” that in his vision of English lordship would be the King’s. DANIE VAN DER MERWE / FLICKR:DanieVDM

South African universities were always segregated, but with the arrival of Apartheid an entire architecture for their racist separation was designed—and implemented with vigor. Apartheid was essentially an architectonic, an architecture of restriction that zoned places of work, dwelling, and leisure in accord with strict racist canons, and limited circulation of persons of color in accord with rigid “pass” laws. It regulated space along principles of identity, citizenship, and circulation. Apartheid’s architecture was formulated to destroy the inevitable intermingling of the “races” that happens in any modern/urban context where lines of conversation and community cannot be foreclosed. Persons of color were consigned to the Bantustans, puppet countries in the scrap of the bush with no resources, situated far from any urban center, and run by corrupt politicians. Yet the intermingling between “races” persisted.

Sometimes the incipient rhythms of modernity were so powerful that the only way of disrupting them was to obliterate an entire city quarter: In the 1930s Sophiatown, a city of color at the edge of Johannesburg, had outgrown its identity as a shanty town filled with violence and poverty to become the slowly emerging centre of a new form of life produced by the urbanized black people who called it home. American influences—Harlem music, Hollywood film—went into a lively, hybridized cultural life of shebeens, jazz, and dancing. In the 1950s, Sophiatown became the seedbed for a new generation of African intellectuals and artists, flâneurs whose gazes, when directed to the white world of the city (from which black people were excluded by law), could not help but become politicized. There all manner of person—intellectual, poet, worker, white, and black—intermingled, and out of that came critical reflection on society. It is no coincidence that the Defiance Campaign of 1952, the first mass mobilization against unjust laws in the country’s history, gestated in areas like Sophiatown, Cato Manor in Durban, and District Six in Cape Town. And so Sophiatown (and later Cato Manor and District Six) had to be destroyed. What the apartheid state required was that a physical gap be opened up between para-city and city proper—because it is a natural concomitant of industrialization that groups mix in space, idea, and identity. Forced removals tore apart the urban fabric through which these new identities and, importantly, solidarities could be woven. And so these cities were reduced to rubble.

The apartheid state separated the so-called races into three categories: White, colored/Indian, and black. These categories were meant to satisfy the different needs and capacities of the racially distinct populations and so allow each of the separate and unequal cultures to flower. A basic building block in this architecture was the university system. New ones were built for the various races, with “black” universities placed in the remotest rural places. The Apartheid system’s idea for these was that they would do no more than develop the new civil service for “the tribes.” There was no intention that these institutions would be involved in the project of knowledge generation. The same was true for the colored and Indian universities, but they were built on the periphery of cities and contained colleges of pharmacy, optometry, and so on, a mid-range professional training ground for a mid-range set of so-called “colored minds.”

Here is the paradox. Out of this architecture formed an intellectual template of resistance, which is still central to South African universities today. It was inevitable that the black universities, the one for colored people, and the one for Indian South Africans became radicalized with fierce struggles between the progressive forces (among students, faculty, and staff) and the institutional regimes that were put in place by the state. Some white liberal universities also opposed the state. The University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg had a plaque in the foyer of its Great Hall stating unconditionally that its principle was in opposition to the government, that it would accept all races and teach without censorship. Wits, of course, followed the law. It had separate residences for students of color and only admitted them when it was legally possible. University of Natal was mixed in its liberalism, supporting leftist faculty even when they were “banned” but also, like the other liberal universities, hiring plenty of conservative academics who would not rock the boat. Students of color thrived in its black medical school (where the Black Consciousness Movement of Steve Biko was born) but were denied access to many facilities. The Afrikaans universities were all fiercely pro-Apartheid, and the University of Pretoria received triple funding from the government because of its allegiance. All are endeavoring to remake themselves today and have something dignified to offer.

Apartheid was the origin of an activist/community-driven model of knowledge production found today in many South African universities. In those days books were censored, and a faculty person could have his or her library searched by the police, leading to being banned. In response to the constant threat of the state to cannibalize the university, the South African university reacted with an epistemic formation that was essentially activist. The presence of activist scholars at many universities in South Africa helped to shape their engagement with the liberation movement, the trade union movement, and local communities, and this became a central feature of the academic profiles of the white liberal universities and the historically black universities. At the University of Natal, in the 1980s and 1990s, as a way of providing protection to community-based organizations from Apartheid’s security apparatus, the infrastructure for more than 80 of these non-governmental, community-based organizations was created. These organizations played an extremely important counter-hegemonic role in the construction of the academic profile of this university. Just prior to the fall of Apartheid, the University of Western Cape was an avowedly Marxist university.

Students from the University of Witwatersrand (Wits) stage a demonstration March 21, 1988 in Johannesburg to commemorate the 28th anniversary of the 1960 Sharpeville shootings and to protest the bannings of the anti-apartheid organizations. TREVOR SAMSON/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

These activist concepts, sometimes of an oversimplified Marxist variety, as in the case of the University of Western Cape, are clearly out of date. This is part of why scholarship at South African universities simultaneously faces the challenge of renegotiating epistemologies of activism and the relevance of the autonomy of the disciplines. The first is an imperative of history—it is what saved the South African university from ignominy. The second—to preserve the autonomy of scholarship without reverting back to a Eurocentric formation—is among the most severe challenges faced by the South African university. To negotiate the needs of autonomy, capacity building, and many duties of a university to its vast, racialized, inequitable society: this is the basic project of South African universities today.

Transformation and Reform

During the early transition to democracy in the 1990s, the template of the activist university in South Africa transmogrified first into a new array of community engagement projects, and then into a more sophisticated struggle for the development of a place for intellectual work in this nascent democracy. This took place even at formerly pro-Apartheid, Afrikaans-speaking universities like Pretoria. Transformation was undertaken in all aspects of university life, from curriculum to institutional structures to senate policies at universities, enrollment of under-represented students en masse, and diversification of faculty and staff. The system was remade through a large platform of new policies that served to make higher education more accountable, more representative of the post-Apartheid political and social landscape, more effective and efficient, more relevant to the needs of reconstruction and development, and more connected to the global competitiveness of the economy. (The imperatives that underpin these policy reforms are not always driven by the best interests of higher education or society. Narrow political agendas sometimes intrude, such as the need for it to appear that universities are as ruled by “transformational change” as any other sector of society. Transformation can become a “show trial” for the state. There have been battles over this.)

Transformational policy was highly successful in remaking student populations and curriculum. When Daniel Herwitz arrived at University of Natal in 1992 to teach for a semester, all but one of his students was white, the one being of Indian descent, and none were black Africans. When he departed for Michigan in 2002, the university was 35 percent students of Indian descent, 33 percent students of African descent, and the rest white. In 2006 more than 80 percent were students of color. This change is driven as much by faculty activism as by the pressure of demographics. The remaking of the curriculum has been equally profound. The prerogative of integrating students with vastly different degrees of preparation and cultural habits, not to mention linguistic differences (Zulu first speakers and often English third speakers), has generated wonderful educational policy and served the larger goal of revisiting heritages of the humanities, social sciences, and remaking the course of mathematical education, teaching of languages, and training in science. These changes have pushed South Africa ahead of many other university cultures. Faculty diversification has been more difficult, given that Apartheid’s greatest success was its educational crippling of a generation. The most obvious effect of Apartheid was to dampen if not kill off black capacity, and the generation that might have returned to universities quickly moved into business and government where salaries escalated with power and status. One of the most difficult issues besetting South African higher education is the retention of faculty of color, who chronically flee to business and state sectors. However, through great innovation, this too has improved in recent years. At UKZN there are now nearly as many faculty members of color as there are white members (among the historically white universities, UKZN leads South Africa in this respect).

If transformation has had its dramatic successes, it has also been subject to a contradiction, which results from the neoliberal formation of the post-Apartheid South African state. That state voluntarily took onto itself the World Bank’s strictures of structural adjustment in order to pay off the international debt incurred by the Apartheid state so as to ready itself for significant foreign investment during the 1990s, and to give itself fiscal space for its reconstruction programs. Its neoliberal agenda was meant to serve the purposes of socialist development by generating income for social transformation in the name of equality. Instead investment poured into China, to the point where some South African companies outsourced production to China. Millions of jobs were lost. It was the same contradiction between socialist goals and neoliberal policy that informed the educational policy handed down from England and Margaret Thatcher to prepare the university to serve the demands of the state. Departments were downsized, costs cut, the market economy introduced into the substance of the university. If classics lost student numbers it would be shaved off the map; if physics did not link up with industry to make a new atom bomb or more likely, power generator, then it too would ride into the sunset. Financial viability became the key determinant. The message here is one can’t expect faculty to deploy imagination while simultaneously under threat. For departments this meant the deployment of imagination toward survival rather than toward postcolonial innovations in knowledge production.

This Thatcherite pressure was meant to cause departments and faculties to serve better “outcomes.” “Outcomes-based education,” the then reigning ideology, would have two sets of goals. First the tertiary educational system would serve the state by producing a new workforce, generating “knowledge-based human capital” for the marketplace. While the economy has indeed had unprecedented growth, the higher education system ended up producing far fewer engineers, scientists, and other key human resources than are needed. Second, the tertiary system would produce a critically thinking graduate, one able to probe the complexities of the present, and negotiate the whirlwind of a society in tumult. The two goals do not sit easily with each other. The first wants the student to pass through the university in the manner of an automobile getting a drive-in oil change: fast and efficiently. The second argues for a slower, more interactive kind of educational curriculum, through which the student would be gradually taught the fine art of reflection and critical thinking. The failure of the policy was that one goal demands rapid turnover, while the other slow rumination.

A society in transition is inevitably one with multiple and partly contradictory demands, and South Africa is no different. If a developing society is unequal, the extent of competition over demands and national budgetary commitments increases exponentially. But contradiction does not ameliorate urgency: South Africa remains today one of the most unequal societies in the world in terms of wealth distribution, with the legacy of deep and unforgiving racialization of this inequality. Transformation has partly backfired because it demanded imaginative transformation from its universities under the threat of elimination, and because it demanded that the university speed up and slow down at the same time. And it has been perceived as backfiring by the state because the expectations placed on universities to solve problems have been too strong. A chronic condition of universities in the global south is that excessive demands are heaped onto them: they are asked to solve too much too quickly. The history of South Africa is that it produced the world’s first heart transplant at the same time that the society was ravaged by the most basic infectious diseases: cholera, tuberculosis, etc. The great successes of the South African university have been directed to a minority population and its needs. To open up the university to solving the needs of the majority is no easy matter.

Diversity and Social Inequities

It was in 2000-2001 that a second phase of university restructuring began: mergers between the three sets of universities. This had to do with justice but also efficiency. Apartheid had produced the most inefficient educational system possible, by designing inequality through separation. Three sets of universities meant three of everything, although not equally. It meant universities in the boondocks where no student would ever wish to go again. It meant universities within 10 minutes of each other. The University of Natal had three electron microscope units—one on the Howard College campus in Durban, one three minutes away at the Medical School campus, and one at its campus of Pietermaritzburg 40 minutes away. Within 10 minutes of the Durban campus was the only Indian university, Durban-Westville, which also had one. In a country of moderate resources this kind of waste proved unacceptable. Three sets of deans, three sets of staff, three sets of buildings, equipment, libraries, and so on: an accounting disaster. The black universities were, with noted exceptions (University of Fort Hare), failing, bleeding money with no students. In 2000, the Minister of Education demanded a restructuring of the system. Natal merged with Durban-Westville, the Rand African University with the Wits Technikon; Pretoria and other universities also merged. The cunning and prestige of certain institutions kept them “pure” (Cape Town, Stellenbosch). And so the exercise became in the first instance a matter of who could avoid what with whom. However, in the second instance, it has produced surprising results, cutting through fusty institutional cultures, generating new kinds of possible projects. The University of Johannesburg has shed its Afrikaans past and become an urban university like Wayne State University or City College of New York, and it is eager to remake its research agenda through its new composition with a technikon. Natal has had dire difficulties with the restructuring process, but it remains at the top of the research output table—second only to the University of Pretoria even after the trauma of the merger. These are universities that have an impressive resilience and institutional imagination. Their claim on the future is vital for Africa and for the global south. Because they have produced in their histories the best of early-twentieth-century engineering, the first heart transplant, two Nobel-prize-winning novelists, world-class historians, architects, and sociologists, because their formation is exemplary, caught between the demands of research autonomy and community-driven activist knowledge production, they are worthy partners for U.S. universities in the fullest sense. There in that society racked by 40 percent unemployment, inadequate housing, health care, and unimaginable disease, knowledge is forced out into the streets to encounter diverse populations and their variable prospects. The researcher is constantly challenged by the extent of human difference in this country of 11 official languages, multiple cultures, rural and urban forms of existence, and overwhelming economic inequality.

The formulation of knowledge production in South African universities is one that recognizes that a scholar, scientist, writer, or artist has to exist between multiple poles. If you are a playwright at the University of Cape Town, you will teach and perform Beckett, Shakespeare, and Chekov, but also work with communities like Clanwilliam to mount new performances integrating African styles of song and performance with people whose claim to knowledge and experience is likely far different from your own. If you are a social scientist, you will write theory, but also work to generate knowledge that is action-oriented within communities at risk of violence when a case of HIV/AIDS is diagnosed and disclosed. What universities cannot do is recede into protected cloisters—knowledge production is here and there—inside the university and outside the university.

South African universities live diversity, they do not simply write about it. And this experience makes their writing and research, at its best, something everyone else can learn from. Their specific social formation is unique. Universities in the United States have something to learn from this.

Diversity also disguises vast social inequality, and African universities find themselves battling to justify their commitments to basic science for that reason. What need have we, it is asked, for new work in mathematics or physics when the social problems of the country are so great and the educational resources so modest? A powerful question, to which one response is: Without first-rate laboratories and scientists to fill it, the South African university would become a world appendage. Were basic science cut off, the entire university would feel the dissipating effect. There are substantial indications that the South African government sees itself as the champion of the basic sciences. It has created the conditions for the national expenditure on science and technology to increase to one percent of GDP—up from 0.7 percent three or four years ago. More importantly it has invested heavily in “big science” such as the Southern African Large Telescope (the largest in the southern hemisphere), and more recently in South Africa’s bid for the Square Kilometre Array (the world’s largest radio telescope). South African science will be international science.

It is not that the American university can simply decide to adopt the conditions of the South African university—its enhanced encounter with diversity, its veering between research autonomy and social commitment, its sweep of transformation—as if social practices were consumer items to be chosen at will. However, the encounter with a truly distinctive university system—inclusive of fault and virtue—provides a vantage point for the American university to reflect upon its own limitations as well as its strengths, so that it may seek to grow into the next generation. The next generation will be an even more global generation than ours, with students more accustomed to zipping around the globe, research projects more collaborative, interconnections between global regions more profound. The key is to enter into these relationships with the sense of something to learn, not merely something to give.

Ahmed Bawa is Professor and Distinguished Lecturer in the Department of Physics and Astronomy of Hunter College, City University of New York. Professor Bawa has spent many years in academic administration in South Africa, including nine years as Deputy Vice Chancellor at the University of Natal. He also worked at the Ford Foundation as program officer for higher education in Africa.

Daniel Herwitz is Director of the U-M Institute for the Humanities, Mary Fair Croushore Professor of Humanities, and the former Director of the Centre for Knowledge and Innovation at the University of Natal in Durban, South Africa which he founded with Ahmed Bawa. He was honored to have been part of the University of Michigan presidential delegation to South Africa last month.