The Chinese Festival Calendar and the Allure of the Double Fifth

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The staging of festivals in traditional China has long been used to highlight community wealth, and showcase regional music, local opera, religious artifacts, and traditional customs. The Dragon Boat Festival is among the three most lavish Festivals of the Living which also include the New Year (2nd new moon after the winter solstice) and the Mid-Autumn Moon (15th day of the 8th month). The allure of this event is as much due to its competitive ambiance as its pivotal location in the calendar. Set to occur close to the summer solstice, the Dragon Boat Festival’s date—the fifth day of the fifth lunar month—is referred to as the Double Fifth or Duan Wu. This time is characterized by a struggle in traditional cosmology between the dual forces of yin and yang. The waxing yang reaches a culminating point with the arrival of the solstice, and the yin principle, symbolizing darkness and dampness, begins its gradual ascent. This is the hottest time of the year associated with the onset of epidemic diseases. Dragon boat races, the heartbeat of the festival, were a symbolic means to rid the surroundings of noxious elements.

The celebration was set to occur when the transplantation of rice was over and torrential summer rains were about to begin. Sinologist Goran Aijmer has suggested that racing dragon boats represented a clan’s struggle against the ancestors of alien lineages whose negative influences might impede the growth of rice. The “ancestors” or rowers recall the soul (hun) of the transplanted rice or “drowned persons” through songs and drumming. The Dragon Boat Festival ends with the triumphant ancestors taking away bad tidings as they return to the land of the dead.

Most Chinese, however, would claim that the festival was designed to recall the soul of Qu Yuan, a loyal minister in the 3rd century BC. According to popular history, Qu Yuan tried to advise the king on how to keep peace with neighboring states, but his advice was rejected and he was banished from the kingdom. When he later learned that the capital city had been destroyed in war, he despaired and wrote one of China’s most famous elegies, the Li Sao (Lament on Encountering Sorrow). Then he threw himself into the Milo River (Hunan Province) and drowned. People got into their boats and raced to find him; but to no avail. Realizing that he had drowned, they threw rice into the water as a sacrifice or, according to some versions of the legend, to prevent the fish from eating his body. To this day, dragon boat races are held to reenact the search for Qu Yuan. The street-fare specialty of the Festival is the rice offering, zong zi, filled with either sweet or savory ingredients, securely wrapped in leaves (lotus, palm, or bamboo) in the shape of cones or cylinders, and tied together with string.

The race itself is a captivating spectacle. Dragon boats are large, canoe-shaped, ranging in size from 40 to 100 feet, with fiery, open-mouth dragon heads at the bow and tails behind. The boats are powered by as many as 80 paddlers, depending on the length of the vessel. According to a late Ming dynasty (1368-1644) text on the dragon boat race in Hunan Province, the ideal crews consisted of strong, experienced men from local fishing villages. Aptly enough, they were nicknamed “water crows” (shui lao ya).

The Dragon Boat Festival continues to enjoy immense popularity today, flourishing both in and outside of Asia. Just as feng shui, tai chi, and Buddhist meditation have become synonymous with methods of self improvement, dragon boat racing has captured the corporate imagination for team building and personal development. Stripped of its spiritual and magico-religious practices, and even its lunar date, dragon boat racing has become one of the fastest growing markets for business retreats globally and in the United States. In some cases, certain rituals are reconfigured to fit a new audience: the custom of “awakening the dragon,” typically conducted by Taoist priests, is now performed by business or community VIPs.

In much the same way that the Chinese almanac rooted in agricultural lore and folk wisdom has changed and adapted to a largely urban overseas Chinese audience, the Dragon Boat Festival prospers worldwide because of its malleability and renao or boisterous ambiance, allowing the opportunity for local innovations and modern transitions.

Carol Stepanchuk is the Outreach Coordinator for the Center for Chinese Studies. This essay is adapted in part from her book, Mooncakes and Hungry Ghosts: Festivals of China, China Books and Periodicals. Her first experience with dragon boat racing occurred this September on the Huron River as part of the LSA China Theme Year.

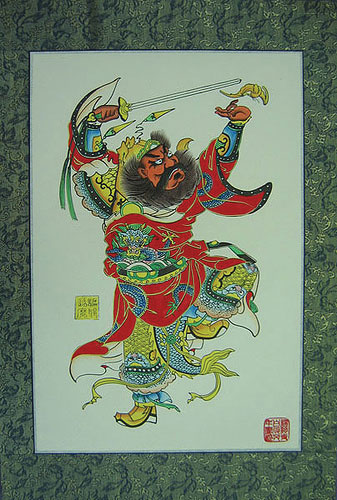

The summer heat of the fifth lunar month required more than dragon boat races to dispel evil and pestilence. Woodblock prints depicting healers and exorcists were hung on doors and walls to safeguard homes and communities. The monster-scholar, Zhong Kui, brandishing his sword or gobbling up ghosts, was a particularly popular image used in traditional festival practice. For additional images of Zhong Kui, see Ellen Johnston Laing, Arts & Aesthetics in Chinese Popular Prints: Selections from the Muban Foundation Collection, Center for Chinese Studies, Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies, Vol. 94, 2002. See nos. 53 and 54.