Iraqi Assessments of the U.S. Presence in Their Country

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The United States invasion and occupation of Iraq have been controversial. Americans themselves are increasingly divided about the wisdom and legitimacy of the Bush Administration's Iraq policy. Although most Americans say sincerely that they "support the troops," many also say that this does not mean they support the war.

There are unresolved questions about the Bush Administration's motives in Iraq. Did American leaders really believe their initial justifications about weapons of mass destruction and a link between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaida? If their real purposes are to be found elsewhere, what, in fact, did the U.S. really seek to accomplish? Several hypotheses have been offered, ranging from George W. Bush's desire to accomplish something that his father's presidency did not, to diverting attention from a troubled economy in 2001 to 2002, to destroying an Arab military force believed dangerous to Israel, and, of course, to gaining access to Iraqi oil.

The Bush Administration has talked increasingly about bringing democracy to Iraq, and thereby helping to set in motion democratic transitions in other Arab states. This has emerged in the last year or so as the principal justification offered by Washington for going to war. Moreover, spokesmen for the Administration already claim some success in this regard, asserting that U.S. actions in Iraq have contributed to progress toward democracy in several other Arab countries. Among the examples they cite are the relatively successful national elections in Iraq and Palestine; municipal elections in Saudi Arabia; and calls by Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak for a constitutional amendment to permit, for the first time in the country's history, direct and competitive multi-party elections for president.

The gains to which the Administration points for the most part are quite modest. An Egyptian journalist described Mubarak's proposed amendment as little more than an attempt by the President to improve his image with the Americans, while leaving unchanged the laws and practices by which the government suppresses opposition and dissent. A Palestinian political scientist, who is also a member of the Legislative Council, observed that it will take far more than elections to build democracy in Palestine. Against this background, a Carnegie Endowment report published in late 2004 concludes that although there has been some talk about political reform and democracy, this is "only palely reflected in the actual changes that have been introduced to date by Arab states." Equally important, with the exception of the Iraqi case, there is no clear evidence of a causal connection between American actions and whatever progress toward democracy may have been made in these countries.

Nevertheless, it is correct that the Arab world lags behind other world regions with respect to democratization, and this is acknowledged and lamented by many Arab intellectuals. For example, the 2002, 2003, and 2004 issues of the Arab Human Development Report, prepared by prominent Arab analysts under the auspices of the United Nations Development Programme, have all complained strongly about the Arab world's "Freedom Deficit." The recently released 2004 report offers a highly critical appraisal of progress toward democratization in Arab countries and emphasizes the immediate need for political reform. Regardless of what may have been the Bush Administration's original motives for the invasion and occupation of Iraq, perhaps U.S. actions will in the end be judged favorably if it turns out that they do indeed advance democratization in Arab countries.

While these issues will continue to be debated, a public opinion survey carried out in Iraq in November and December 2004 provides an unusual opportunity to learn what ordinary Iraqis think about the American presence in their country; to find out whether or not these men and women want democracy in Iraq—and what kind of democracy; and to explore a possible linkage between their views about the American invasion and about democracy.

With support from the National Science Foundation, the survey was designed and directed by Professors Mark Tessler and Ronald Inglehart of the University of Michigan and Professor Mansoor Moaddel of Eastern Michigan University. The team worked in close collaboration with Iraqi scholars at the Independent Institute for Administration and Civil Society Studies, based in Baghdad. The survey used area probability sampling techniques to select respondents in 16 of Iraq's 18 provinces—conditions did not permit the survey to be conducted in Ninawa and Dahuk. A total of 2,325 respondents were interviewed, of whom 68.9 percent reside in urban areas and of whom 61 percent are Shi'a, 22.5 percent are Sunni, and 16.5 percent are Kurdish. The sample was also generally representative in other respects: 51.7 percent of the respondents are female; 30.6 percent have had less than a primary school education and 13.3 percent have completed university; and 33.8 percent are between the ages of 18 and 29 and 15.1 percent are over the age of 50.

The first and perhaps most striking finding is that attitudes toward the U.S. are overwhelmingly negative. Asked whether they trust American forces in Iraq, 74 percent said not at all and another 13 percent said only a little. Asked it they support the presence of American forces in their country, 61 percent said not at all and another 13 percent said only a little. Only 11 percent both trust American forces and support their presence in Iraq.

Anti-American sentiment is found among respondents in almost all demographic categories. There are only small differences in the views of men and women, older and younger persons, and better and less well educated individuals. This is not to say there are no differences among categories of respondents, however. Not surprisingly, anti-Americanism is strongest among the Sunnis—only 3 percent have "much" or even "some" trust in American forces, and only 5 percent express either "much" or "some" support for the American presence in Iraq. At the opposite end of the spectrum are the Kurds: 67 percent have at least some trust in American forces, and fully 80 percent express at least some support for the American presence in Iraq.

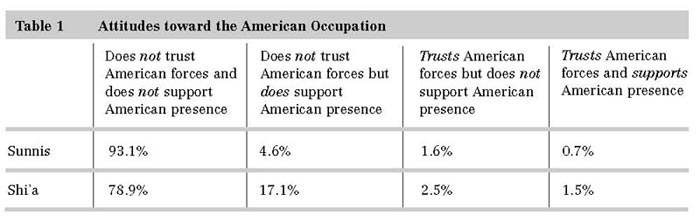

The attitudes of the Shi'a constitute an intermediate case but are also more complex. The broad anti-Americanism of the sample as a whole to a large extent reflects the views of this important ethno-religious community. In contrast to the Sunnis, however, some Shi'a distinguish between trust and support with respect to the American occupation. As shown in Table 1, most Sunnis neither trust American forces nor support their presence in Iraq. By contrast, 17 percent of the Shi'a respondents support the American presence even though they have little or no trust in the Americans.

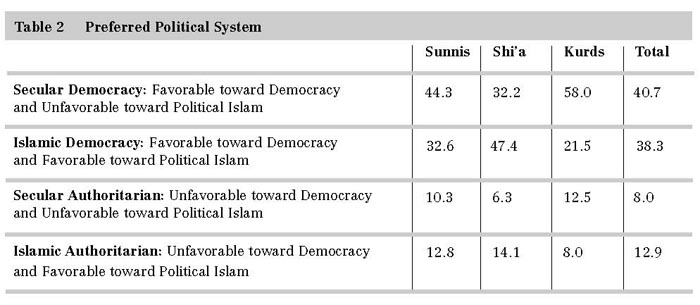

Turning to attitudes toward democracy, two points stand out. First, the vast majority of Iraqis say that they would like to have a democratic political system in their country. Second, a plurality of all respondents and almost half of the Shi'a respondents embrace a concept of democracy that is not secular but rather assigns an important place to Islam. This is shown in Table 2, which has been constructed from indices based on a series of survey items pertaining to democracy and political Islam.

Is there a connection between Iraqi thinking about democracy and Iraqi attitudes toward the U.S. occupation? Does a desire for democracy, either democracy in general or secular democracy in particular, lead at least some Iraqis to a less critical view of the American presence? The logic of this argument is that if American actions advance the cause of democracy, regardless of U.S. motives in coming to Iraq, then those who want democracy to take root in Iraq will judge there to be at least some important benefits emerging from the occupation. On the other hand, it is possible that Iraqi advocates of democracy see things differently, perhaps believing that the occupation will preside over the establishment of a political system that has the superficial trappings of democracy but in reality serves American rather than Iraqi interests.

Table 3 shows that support for democracy is associated to a modest degree with reduced anti-Americanism but that the connection between these two sets of attitudes is neither strong nor simple. The table shows the following patterns. First, those who favor secular democracy in Iraq are less likely than others to neither trust American forces nor support their presence in Iraq. Nevertheless, this is the position of two-thirds of these respondents, so opposition to the American project in Iraq certainly remains strong among advocates of secular democracy.

Second, supporters of both secular democracy and Islamic democracy are more likely than those who do not favor democracy to distrust American forces but, at the same time, to be at least somewhat supportive of the American presence. Again, differences between the views of Iraqis who do and do not support democracy are not large, but they are nonetheless notable and consistent in direction. This suggests that some who favor democracy, including Islamic democracy, more so than others, couple their dislike of the American occupation with a judgment that something positive may nonetheless result.

Third, the American presence appears to be judged according to religious as well as political criteria. This is suggested by the fact that distrust of American forces coupled with opposition to the U.S. presence is lower among advocates of secular democracy than among advocates of Islamic democracy and, equally significant, it is also lower among advocates of secular authoritarianism than among advocates of Islamic authoritarianism. The same is true among the relatively few who both trust American forces and support the U.S. presence: those who express this view are more likely than others to favor a political system, whether democratic or not, that does not assign an important role to Islam.

In conclusion, there is no doubt that most Iraqis have an unfavorable view of the role the U.S. is playing in their country. This is undoubtedly fueled by the dire economic situation and a lack of security in many areas. Opposition to the U.S. is almost certainly deeper, however, reflecting a basic distrust of American motives and intentions. But the present analysis sheds light on an additional part of the story. It shows that judgments about the American project in Iraq are conditioned to at least some extent by the ethno-religious differences among Iraqis and by the differing views of ordinary men and women about the kind of political system they would like to see established in their country.

Mark Tessler is Samuel J. Eldersveld Collegiate Professor of Political Science, vice provost for international affairs, and director of the International Institute at U-M.