Determinants of Article Processing Charges for Medical Open Access Journals

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

For-profit subscription journal publishers recently have extended their publishing range from subscription journals to numerous open access journals, thereby strengthening their presence in the open access journal market. This study estimates the article processing charges for 509 medical open access journals using a sample selection model to examine the determinants of the charges. The results show that publisher type tends to determine whether the journal charges an article processing charge as well as the level of the charge; and frequently cited journals generally set higher article processing charges. Moreover, large subscription journal publishers tend to set higher article processing charges for their open access journals after controlling for other factors. Therefore, it is necessary to continue monitoring their activities from the viewpoint of competition policy.

Keywords: Open access journal, Article processing charge, Sample selection model, Publisher

Introduction

Since the 2000s, open access journals have developed as an innovative medium to read academic literature free of charge in a context of continuously increasing journal subscription prices. There are three categories of open access journals by publisher type. First, some journals are launched by a research institution, such as an academic society or a university. Second, some journals are launched by an open access journal publisher, such as the Public Library of Science (PLOS), or a subscription journal publisher, such as Elsevier. The third category comprises a combination of these two types, that is, journals launched as a collaboration between a research institution and a journal publisher. The last category comprises journals that are usually edited by the institution and published on the publisher’s website.

In the case of open access journals financed through an article processing charge (APC), production costs are transferred to authors instead of journal readers. However, according to Shamash (2016), research institutions to which authors belong often pay APCs imposed on authors to promote open access. Thus, high APCs pose an economic burden on authors or research institutions. Pinfield et al. (2017) investigated both payment for subscription journals and APCs by research institutions in the United Kingdom (UK), and found that their expenditures on APCs accounted for 11.8 percent of all expenditure on academic literature in 2014. Therefore, the APC levels are important for both authors and research institutions.

Alongside the growth of open access journals, traditional subscription journal publishers have launched many open access journals in addition to hybrid journals that give authors the choice of publishing open access articles within subscription journals. Based on the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), Elsevier, Springer, SAGE, and Taylor & Francis—all traditional subscription journal publishers—are among the top 10 publishers as measured by the number of open access journal titles. Shulenburger (2016) argued that an increase in the prices of subscription journals is partly caused by the imbalance of market power between libraries (buyers) and journal publishers (sellers). In addition, Shulenburger (2016) discussed the possibility of publishers with comparatively large market power raising APCs, because individual authors do not have the ability to negotiate APCs with publishers. Siler (2017) argued that the APC publishing model may increase the market power of publishers, albeit solving the problem of accessibility to academic literature. Since large subscription journal publishers have strengthened their presence in both the open access as well as subscription journal markets, their activities with regard to open access journals deserve scholarly attention.

However, Morrison (2018) showed that non-APC journals account for 62.8 percent among 11,836 open access journals with information on publication fees; Crawford (2018) reported that 69.7 percent of open access journals do not charge any APCs. Although my focus here is on APCs, about two-thirds of open access journals do not impose APCs. Just as there are multiple categories of open access journals by publisher type, their revenue sources differ among publishers. Therefore, this study identifies the characteristics of journals by publisher type and then examines the determinants of APCs, including whether to impose them. Although hybrid journal publishers impose APCs on authors who select open access, the journals are subscription ones. This study focuses on the APCs for gold open access journals and does not deal with the APCs for hybrid journals. Although many studies investigate the APCs for gold open access journals, there are few econometric studies that examine the exercise of market power by large subscription journal publishers in the open access journal market thus far. This study provides material for design of competition policy through the determinants of APCs.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The next section surveys the related literature. The third section outlines the current state of open access journals in the field of medicine to identify the characteristics of journals by publisher type. The fourth section explains the sample selection model and data for examining the determinants of APCs. The fifth section reports the estimation results. The sixth section discusses the implications of the findings. The final section concludes.

Related Literature

APCs for open access journals correspond to prices for subscription journals, although there is a difference in the sense that APCs are paid by authors or research institutions and subscription fees are generally paid by libraries. Empirical studies on individual subscription journal prices are useful for establishing variables for APC estimation. Therefore, empirical studies on the prices of subscription journals as well as APCs are significant for the present study.

Regarding subscription journals, Petersen (1990) estimated the subscription prices of academic journals using such variables as the number of issues, advertising, number of pages, type of publisher, and academic field, by ordinary least squares (OLS), and reported that the library prices of journals launched by for-profit publishers are higher than those launched by non-profit associations. Petersen (1992) added the variables of journal citation count and number of circulations per issue to the model of Petersen (1990) and estimated the subscription prices for 81 economic journals. Petersen (1992) found that the prices of more frequently cited journals launched by for-profit publishers are higher and that a negative coefficient for number of circulations reflects economies of scale in journal publishing. Chressanthis and Chressanthis (1994) estimated the library prices for economic journals using variables representing the number of circulations, citation count, and type of publishers, and found that the coefficient for citation count is positive while for-profit publishers set higher prices. Moreover, Chressanthis and Chressanthis (1994) found that the number of circulations is negative, indicating that publishers have economies of scale.

Although subscription journal prices were often empirically studied in the early 1990s, Bergstrom (2001) pointed out that data on the number of circulations of a journal were not available after around 2000, posing an obstacle to estimating subscription journal prices. Furthermore, researchers’ interest in the individual subscription journal prices gradually waned in the 2000s after the penetration of the so-called “Big Deal” bundling service, in which the publisher provides all electronic journals under the condition that research institutions continue to purchase the subscription journals. Nevertheless, considering that the pricing of such bundling services is based on individual subscription journal prices, Dewatripont et al. (2007) estimated journal prices for libraries using variables denoting citation score, type of publisher, and academic field, finding that for-profit publishers set higher prices than academic societies and that citation score had a positive impact on prices. Moreover, Dewatripont et al. (2007) investigated the relationship between prices and journal shares of publishers, finding that publishers with greater shares set higher prices.

Recently, several universities have discontinued Big Deal contracts with subscription journal publishers because of the high prices. Accordingly, concern for individual journal prices has grown among universities and researchers. Liu and Gee (2017) estimated the subscription journal prices in semilogarithmic equation by OLS, finding that for-profit publishers overcharge libraries. Coomes et al. (2017) estimated the prices of subscription journals in the field of geography using OLS and found that for-profit publishers, particularly those with large journal shares, set higher prices. These studies suggested that large subscription journal publishers exert monopoly power when setting prices. By contrast, Dubois et al. (2007) estimated the demand for subscription journals by an aggregated nested logit model, and found that price elasticities are high, and therefore, the margins are relatively low.

Regarding open access journals, Crawford (2018) and Morrison (2018) are useful to understand the overall open access journal market. In addition, Solomon and Björk (2012) found that the APCs for biomedical journals are higher than those for journals in the social sciences and the arts and humanities, indicating that APCs differ among academic fields. Solomon and Björk (2012) and Wang et al. (2015) found that APCs for frequently cited journals tend to be higher. Björk and Solomon (2015) calculated the correlation coefficient between APCs and citation indexes in Scopus in 2011, and reported that the journal-level and article-level correlations are 0.40 and 0.67, respectively. Pinfield et al. (2017) reported a strong positive correlation between APCs applied in 2014 and citation index scores in Scopus. This correlation for open access journals corresponds to the results of empirical studies of subscription journals—that there is a positive relationship between the citation scores of subscription journals and subscription fees. Moreover, Asai (2019) estimated the APCs for BMC (formerly BioMed Central) open access journals by a sample selection model in 2018, finding that BMC sets higher charges for more frequently cited journals. However, since Asai (2019) focused on BMC, it is inappropriate to generalize about the determinants of APCs from the findings.

Overview of Open Access Journals in Medicine

Data Collection

This study focuses on the field of medicine in which there has been a proliferation of open access journals, given that Solomon and Björk (2012) found that APCs differ among academic fields. The observations comprise 509 medical open access journals indexed in the DOAJ database as of April 2018. This study examines journals that accept (1) only English-language articles or (2) English-language and other-language articles. Journals that do not accept English-language articles are excluded, because such journals may have specific local characteristics.

This study uses APCs applied in 2018 and measured in US dollars (USD). An announcement about the APC to be applied in a given year is made the year before, at the latest. If open access journal publishers plan to modify an APC to be applied in 2018, then the number of articles in a journal and the citation score in 2016 may be considered, as these form the most recent data available in 2017 when the APC is set. Therefore, this study uses the number of articles and the citation scores in 2016. The latter, called CiteScore2016, is defined as the number of citations in 2016 divided by the number of articles from 2013 to 2015, and is available from the Scopus database. Based on the DOAJ, the journals are categorized as published in the United States (US), the UK, Europe excluding the UK, Asia, South America, and other regions (Africa, Oceania, and Central and North America excluding the US).[1]

Publisher Type

Table 1 provides an overview of the 509 medical open access journals by publisher type. Both the mean and median for APCs and the number of articles in a journal are reported in Table 1, because their standard deviations are especially large. Regarding the journals independently launched by publishers, 97 of 115 journals (84.3 percent) are financed by APCs. The mean and median APCs are more than 1,200 USD,[2] which poses an economic burden on authors or research institutions. However, the remaining 18 journals (15.7 percent) do not impose APCs, although they are not related to research institutions. The number of articles in the 97 APC-funded journals ranges from 3 to 22,054 (mean 614, median 34), which leads to a large difference between the mean and median of the number of articles in the 115 journals. By contrast, the number of articles in the 18 non-APC journals ranges from 4 to 66 (mean 27, median 23), denoting that APC-funded journals generally publish more articles than non-APC journals publish. Moreover, the mean CiteScore for the 97 APC-funded journals is 1.204,[3] while that for the 18 non-APC journals is only 0.144. Therefore, publishers refrain from imposing APCs for journals with small numbers of articles and low or zero CiteScore. Of the 115 journals, 13 are independently launched by large for-profit subscription journal publishers known as the Big 5: Elsevier, SAGE, Springer, Taylor & Francis, and Wiley.[4] Only 1 of the 13 journals did not impose APCs as of April 2018.

Regarding journals independently launched by research institutions, only 43 of 235 journals (18.3 percent) are financed by APCs. The mean and median of APCs for the 43 journals are significantly low, indicating that even APC-funded journals are partly supported by research institutions. Thus, the publisher type tends to determine whether the journal charges an APC, and if so, the level of the APC. Only 53 of the 235 journals are indexed in Scopus, and the ratio (22.6 percent) is lower than that of journals independently launched by publishers (48.7 percent). Like for journals independently launched by publishers, the characteristics of the 235 journals differ between the APC-funded and non-APC journals. The mean number of articles in the 43 APC-funded journals (88.5) is significantly larger than that in the 192 non-APC journals (58.7) at the 10 percent level. The mean CiteScore for the APC-funded journals (0.390) is significantly larger than that for the non-APC journals (0.114) at the 1 percent level. Therefore, the journals independently launched by research institutions that have a small number of articles and low CiteScore tend to be entirely financed by the institutions’ funds.

Regarding the 159 journals launched in collaboration with research institutions and publishers, the mean CiteScore for the 42 APC-funded journals (0.955) is significantly larger than that for the 117 non-APC journals (0.317) at the 1 percent level. Moreover, the mean number of articles in the APC-funded journals (112.0) is significantly larger than that in the non-APC journals (57.8) at the 10 percent level. Of the 159 journals, 46 are related to Big 5 publishers and 17 of them are financed by APCs. Many subscription journals are edited by academic societies and published by for-profit publishers; such collaboration between research institutions and Big 5 publishers is also observed in the open access market.

Analyzing the data by country or region, the UK has 78 open access journals. 49 of the 78 journals (62.8 percent) are independently launched by publishers, whereas journals independently launched by publishers in Asia account for only 5 percent (9 of 180 journals). The number of journals by publisher type differs remarkably among publishing countries and regions. Thus, open access journals are regarded as a means of doing business in the US and the UK, whereas research institutions in Asia and South America have published them for the free dissemination of knowledge.[5]

Finally, journals that accept only English-language articles account for 76.2 percent of the 509 medical journals. Such journals account for only 27.5 percent (14 of 51) of total journals published in South America,[6] whereas all journals in the US and the UK accept only English-language articles, as may be expected.

| Institution | Publisher | Mix | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of journals | 235 | 115 | 159 | 509 |

| Number of APC-funded journals | 43 | 97 | 42 | 182 |

| Mean APCs (USD) | 371.5 | 1,234.8 | 1,178.9 | 1,018.0 |

| Median APCs (USD) | 180.7 | 1,223.7 | 1,011.7 | 763.5 |

| Number of journals in Scopus | 53 | 56 | 72 | 181 |

| Mean CiteScore2016 | 0.164 | 1.039 | 0.486 | 0.462 |

| Mean number of articles in a journal | 64.2 | 522.4 | 72.1 | 170.2 |

| Median number of articles in a journal | 35.0 | 32.0 | 42.0 | 37.0 |

| Number of English journals | 148 | 111 | 129 | 388 |

| Number of journals in the US | 11 | 13 | 2 | 26 |

| Number of journals in the UK | 6 | 49 | 23 | 78 |

| Number of journals in Europe excluding the UK | 53 | 36 | 59 | 148 |

| Number of journals in Asia | 108 | 9 | 63 | 180 |

| Number of journals in South America | 45 | 2 | 4 | 51 |

| Number of journals in other regions | 12 | 6 | 8 | 26 |

Model and Data

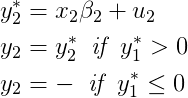

This section estimates the APCs for 509 medical journals to examine the determinants of APCs. First, publishers have the choice either to impose or not to impose APCs and, subsequently, the determination of the APC level. Two-thirds of the 509 journals refrain from imposing charges. When APCs for many open access journals equal 0, the estimates in APC equation by OLS are biased and inconsistent.[7] Therefore, this study adopts a sample selection model. Numerous empirical studies, especially in labor supply (Wang and Ge, 2018), have already used this model, including Asai (2019), who used the model to estimate APCs. Studies that formulate two-step decisions by players usually use Heckman’s two-step estimator. However, Nawata (2004) found that the performance of the maximum likelihood estimator is better than that of the Heckman procedure, judging from the standard errors and bias. Based on Nawata (2004), this study estimated the equations using both the Heckman procedure and maximum likelihood method. The results confirmed that the performance of the latter is superior, as Nawata (2004) pointed out, although the differences in the coefficients between the two methods are small. Therefore, the present study uses the maximum likelihood method to estimate the two equations. This model comprises a participant equation (1) and an outcome equation (2), where x is the explanatory variable, y* is the latent variable, and β is a parameter:

| (1) | ||

| (2) |

u1 and u2 are error terms that follow a bivariate normal distribution with standard deviation σ and correlation coefficient ρ:

The participant equation concerning whether to charge APCs and the outcome equation for the level of APCs are specified by equations (3) and (4), respectively:

| (3) | ||

| (4) |

In equation (3), the dependent variable Fee is set to 1 if the journal imposes an APC, and is 0 otherwise. The independent variable Cite denotes the CiteScore2016, and Article denotes the number of articles in a journal in 2016. ln represents the natural logarithm. Scopus is set to 1 if the journal is indexed in the Scopus database, and is 0 otherwise. English is set to 1 if the journal accepts only English-language articles, and is 0 otherwise. Publisher is set to 1 if the journal is independently launched by an open access journal publisher or a subscription journal publisher, and is set to 0 otherwise. Institution is set to 1 if the journal is independently launched by a research institution, such as an academic society or a university, and is set to 0 otherwise. US is set to 1 if the journal is published in the US, and is 0 otherwise. UK is set to 1 if the journal is published in the UK, and is 0 otherwise. Europe is set to 1 if the journal is published in Europe, excluding the UK, and is 0 otherwise. Similarly, Asia and SouthAmerica are independent variables denoting the respective publishing regions.

Independent variables Waiver and Big 5 are used only in equation (4). Waiver is set to 1 if the journal has a waiver policy on APC payments, and is 0 otherwise.[8] Big 5 is set to 1 if the journal has been published by any of the Big 5 publishers, and is 0 otherwise. The journals include those published in collaboration with research institutions.

This study also separately estimates 388 journals that accept only English-language articles, since the ratio of articles written in English in a journal significantly differs among journals. In this case, the variable SouthAmerica is not included in the two equations for the 388 journals, because all the English-language journals published in South America are non-APC journals.

Table 2 reports the statistical description of the 509 observations by fee status. The first rows show the means, and the second rows in parentheses show the standard deviations. There are differences in the number of articles, CiteScore, publisher type, and publishing country or region between APC and non-APC journals. The mean APC is 1018.0 USD while the median is 763.5 USD. A significant difference in the two values denotes that the APC distribution has a long tail in a positive direction. The means of the number of articles in an APC-funded journal and a non-APC journal are 374.1 and 56.7, respectively; the null hypothesis that the two means are equal is rejected at the 5 percent level. The mean of Cite for APC-funded journals (0.955) is significantly larger than that for non-APC journals (0.188) at the 1 percent level. Thus, journal characteristics differ between APC-funded and non-APC journals.

Among the 182 APC-funded journals, there are 29 journals related to the Big 5 publishers. Of the 29 journals, 17 are launched in collaboration between research institutions and Big 5 publishers, while 12 are independently launched by the Big 5 publishers. The mean APC for the 12 journals is 1,440 USD, and the mean Article is 1,930, which are both significantly larger than the corresponding figures for the overall 182 APC-funded journals. Conversely, the mean Article for the 17 journals published in collaboration with research institutions is small at 56. However, among the 29 APC-funded journals related to the Big 5 publishers, no significant differences are found in the means of APC and Cite between the 17 journals launched in collaboration with research institutions (1,627 USD, 1.020) and the 12 journals independently launched (1,440 USD, 1.388).

Among the 327 non-APC journals, there are 30 journals related to the Big 5 publishers. The mean Cite for these 30 journals is 0.291, and the mean Article is 72. Although the two means are larger than those for the overall 327 non-APC journals, the differences are small.

| Total | APC-funded | Non-APC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fee | 0.358 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.480) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| APC | 364.0 | 1018.0 | 0.000 |

| (723.4) | (894.0) | (0.000) | |

| Article | 170.2 | 374.1 | 56.7 |

| (1359.2) | (2260.1) | (81.4) | |

| Cite | 0.462 | 0.955 | 0.188 |

| (1.108) | (1.612) | (0.510) | |

| Scopus | 0.356 | 0.484 | 0.284 |

| (0.479) | (0.501) | (0.452) | |

| Publisher | 0.226 | 0.533 | 0.055 |

| (0.419) | (0.500) | (0.228) | |

| Big 5 | 0.116 | 0.159 | 0.092 |

| (0.320) | (0.367) | (0.289) | |

| Institution | 0.462 | 0.236 | 0.587 |

| (0.499) | (0.426) | (0.493) | |

| Waiver | 0.212 | 0.549 | 0.024 |

| (0.409) | (0.499) | (0.155) | |

| English | 0.762 | 0.912 | 0.679 |

| (0.426) | (0.284) | (0.468) | |

| US | 0.051 | 0.093 | 0.028 |

| (0.220) | (0.292) | (0.164) | |

| UK | 0.153 | 0.374 | 0.031 |

| (0.361) | (0.485) | (0.172) | |

| Europe | 0.291 | 0.258 | 0.309 |

| (0.455) | (0.439) | (0.463) | |

| Asia | 0.354 | 0.198 | 0.440 |

| (0.479) | (0.399) | (0.497) | |

| South America | 0.100 | 0.038 | 0.135 |

| (0.301) | (0.193) | (0.342) | |

| Observations | 509 | 182 | 327 |

Estimation Results

Table 3 reports the estimation results of equations (3) and (4) for the 509 journals. Concerning equation (3), which covers the decision on whether or not to charge APCs, the coefficients of Article and Cite are significantly positive at the 5 percent level, denoting that the frequently cited journals that publish more articles tend to be financed by APCs. In other words, this result implies that an unpopular journal might choose not to charge an APC in order to attract article submissions. The coefficient of Publisher is significantly positive and large at the 1 percent level, implying that journals that are not related to research institutions cover their costs through APCs. These estimation results corroborate the journal characteristics as shown in Table 1. The coefficient of the variable UK is the largest among the coefficients of the variables representing publishing country and region, suggesting the penetration of APC-funded journals in the UK.

Concerning equation (4) on the APC determinants, the coefficient of Article is negative, unlike that in equation (3). However, the null hypothesis that the coefficient equals 0 is not rejected at the 10 percent level. The coefficient of Cite is significantly positive at the 1 percent level, implying that frequently cited journals set higher APCs. If the CiteScore for each of the 88 APC-funded journals indexed in Scopus rose by one point, the mean of estimated APCs would then increase from 846 USD to 986 USD using the estimates and variables for individual journals. The positive values for the variables Big 5 and Publisher and the negative value for Institution denote that APCs for journals published by large for-profit publishers are relatively high, whereas research institutions set lower APCs for their journals. If the 182 APC-funded journals were to be published by the Big 5 publishers, the mean estimated APC using the estimates and variables for individual journals would be 697 USD. Conversely, if the 182 APC-funded journals were to be independently launched by research institutions, the mean estimated APC would be 591 USD. The differences between the mean APCs for the APC-funded journals published by the research institutions and the Big 5 publishers may be partially attributed to the fact that some research institutions reduce their APCs by subsidizing the journals, whereas journals published by for-profit publishers principally cover their costs by APCs. However, the coefficient of Big 5 is larger than that of Publisher, denoting that Big 5 publishers have special characteristics that enable higher APCs. The coefficient of English is significantly positive and large at the 1 percent level, implying that the larger readership of English-language journals enables journals to set higher APCs. The coefficients of the variables US and UK are significantly positive and large, whereas the coefficient of Asia is close to 0. Thus, the journals launched in Asia serve as low-cost scholarly communications, whereas journals in the US and the UK meet business objectives.

| Fee: Equation (3) | ln APC: Equation (4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | –1.9343 (0.4606)*** | 4.2603 (0.6172)*** |

| ln Article | 0.1504 (0.0721)** | –0.0265 (0.0516) |

| Cite | 0.2900 (0.1306)** | 0.1531 (0.0568)*** |

| Scopus | –0.0343 (0.1852) | 0.0956 (0.1706) |

| Publisher | 1.5097 (0.2068)*** | 0.0272 (0.2104) |

| Big 5 | 0.3817 (0.2001)* | |

| Institution | 0.0689 (0.1670) | –0.3775 (0.2239)* |

| Waiver | 0.5171 (0.1708)*** | |

| English | 0.2455 (0.1916) | 1.3534 (0.3277)*** |

| US | 0.7156 (0.4274)* | 1.1826 (0.4044)*** |

| UK | 1.4113 (0.3911)*** | 0.9340 (0.3695)** |

| Europe | 0.1867 (0.3473) | 0.5095 (0.3695) |

| Asia | 0.1152 (0.3443) | –0.0873 (0.3867) |

| SouthAmerica | 0.0079 (0.4129) | 0.8023 (0.5670) |

| ρ | –0.3028 (0.1869) | |

| Log likelihood | –450.72 | |

| AIC | 1.8810 | |

Table 4 reports the estimation results of equations (3) and (4) for 388 journals that accept only English-language articles. In Table 4, the positive and negative signs of the coefficients in equation (3), except for the variable Institution, which is not significant at the 10 percent level, are the same as those in Table 3. Similarly, except for the variables Scopus and Asia, which are not significant at the 10 percent level, the signs of the coefficients for equation (4) in Table 4 are the same as those in Table 3. Furthermore, the differences in the values of coefficients between Tables 3 and 4 are small for both equations. Therefore, the conclusions from the two different sets of observations remain unchanged.

| Fee: Equation (3) | ln APC: Equation (4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | –1.7143 (0.4204)*** | 5.6834 (0.4859)*** |

| ln Article | 0.0825 (0.0778) | –0.0319 (0.0506) |

| Cite | 0.3571 (0.1381)** | 0.1790 (0.0566)*** |

| Scopus | –0.1396 (0.2157) | –0.0559 (0.1749) |

| Publisher | 1.5327 (0.2186)*** | 0.0656 (0.2068) |

| Big 5 | 0.4270 (0.1931)** | |

| Institution | –0.0262 (0.1862) | –0.1520 (0.2230) |

| Waiver | 0.5421 (0.1723)*** | |

| US | 0.9890 (0.4038)** | 1.1134 (0.3952)*** |

| UK | 1.6916 (0.3668)*** | 0.8810 (0.3660)** |

| Europe | 0.5755 (0.3252)* | 0.3815 (0.3885) |

| Asia | 0.4605 (0.3186) | 0.0676 (0.3751) |

| ρ | –0.4237 (0.1909)** | |

| Log likelihood | –374.83 | |

| AIC | 2.0558 | |

Discussion

Journal characteristics, including the level of APCs, the number of articles, and CiteScore, differ between journals that are independently launched by research institutions and by publishers. In other words, such publisher types lead to variations in journal characteristics. Moreover, most open access journals published in Asia and South America are related to research institutions and serve as low-cost scholarly communications, whereas those in the US and the UK can be generally regarded as journals serving business objectives. When referring to open access journals, it is necessary to clarify which category of open access journal is being discussed.

Although there are fewer APC-funded journals independently launched by publishers than non-APC journals related to research institutions, the former group has a large impact in academia judging from the numbers of citations and articles. Although research institutions might not charge any APCs to attain a high CiteScore through peer review of many articles, it seems that this approach has not been effective to date. However, not every APC-funded journal is able to attract many submissions. This study shows that about 15 percent of journals independently launched by publishers refrain from imposing APCs, although some cases may be temporary. Open access journals compete to attract excellent articles irrespective of publisher type.

The estimation results show that Big 5 publishers tend to set higher APCs for their open access journals after controlling for other factors. Since several empirical studies on subscription prices have found that for-profit publishers, particularly the Big 5, set higher prices for their subscription journals than non-profit publishers, the results for open access journals are consistent with those of subscription journals. However, it would be premature to conclude from the estimation results that large subscription journal publishers exert monopoly power in the open access journal market for the following two reasons. First, whereas journals independently launched by publishers are financed by APCs, journals related to research institutions are generally subsidized from the institution’s funds, which enables a lower or no APC to be set. Therefore, it is reasonable that APCs for journals independently launched by publishers are higher than those for journals related to research institutions. When analyzing APCs, the influence of subsidies from other funds should be considered. However, since the positive coefficient of Big 5 is larger than that of Publisher, there is no denying that Big 5 publishers set higher APCs for medical open access journals.

Second, although the phenomenon of setting higher prices is common to both subscription and open access journals, the implications differ between them. On the one hand, Dewatripont et al. (2007) and Coomes et al. (2017) concluded that high subscription journal prices may be partly caused by the market power of the large for-profit publishers. On the other hand, authors decide the journals that they submit their articles, although journal options may be limited, depending on the discipline. The publication of many articles in the open access journals launched by the Big 5 publishers is attributed to the fact that many authors choose to submit their articles to these journals.[9] The brand of the Big 5 publishers and the high citation scores of their open access journals attract article submissions irrespective of high APCs. If research institutions or funders provide APC subsidies for authors who belong to the institutions, then researchers would not hesitate to submit their articles to the prestigious Big 5’s open access journals despite high APCs. Therefore, it may be overly optimistic to consider that the continued development of open access journals will reduce research institutions’ expenditure on academic literature. Although it is reasonable for researchers (especially those to whom APC subsidies are provided) to submit their articles to prominent open access journals to grow their reputations, such activities may raise APCs. Considering that open access journals have emerged as a countermeasure to the increased prices of subscription journals, continued monitoring of the market is necessary.

Conclusion

This study examined the 509 open access journals in the field of medicine and found that the characteristics of open access journals significantly differ between those independently launched by research institutions and those independently launched by publishers. This study examined the determinants of APCs using the sample selection model, and found that open access journals independently launched by publishers in the US and the UK tend to select APC-funded models. The estimation results also show that frequently cited journals and journals published by large subscription journal publishers set higher APCs. Large for-profit publishers have strengthened their presence in the open access journal as well as subscription journal markets. Therefore, it is necessary to monitor their activities in the open access journal market.

This study has the following limitations. First, although this study examines journals in the field of medicine, which has witnessed a proliferation of open access journals, the sample of APC-funded journals, particularly journals related to the Big 5 publishers, is not large enough to attain robust conclusions. Further investigation employing more observations of APC-funded journals independently launched by publishers is necessary to conclude definitively whether large subscription journal publishers exert monopoly power in the open access journal market. Second, the business model of open access journals continues to evolve. This study does not deal with APCs for hybrid journals and read-and-publish deals, which are bundled payments for subscription journals and APCs; those issues remain for future works.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant number 15K03470.

References

- Alperin, J. P. “Assessing growth and use of open access resources from developing regions: The case of Latin America,” Alperin, J. P., D. Babini, and G. Fischman, eds. Open Access Indicators and Scholarly Communications in Latin America. 2014. http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/se/20140917054406/OpenAccess.pdf (accessed October 1, 2019) .

- Asai, S. “Changes in revenues structure of a leading open access journal publisher: The case of BMC.” Scientometrics, 121 (1), 2019: 53–63.

- Bergstrom, T. C. “Free labor for costly journals?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15 (3), 2001: 183–198

- Björk, B.-C., and D. Solomon. “Article processing charges in OA journals: Relationship between price and quality.” Scientometrics, 103 (2), 2015: 373–385.

- Chressanthis, G. A., and J. D. Chressanthis. “The determinants of library subscription prices of the top-ranked economics journals: An econometric analysis.” Journal of Economic Education, 25 (4), 1994: 367–382.

- Coomes, O. T., T. R. Moore, and S. Breau. “The price of journals in geography.” The Professional Geographer, 69 (2), 2017: 251–262.

- Crawford. W. “GOAJ3: Gold open access journals 2012–2017.” 2018. https://walt.lishost.org/2018/05/goaj3-gold-open-access-journals-2012-2017/ (accessed March 27, 2019).

- Dewatripont, M., P. Legros, V. Ginsburgh, and A. Walckiers. “Pricing of scientific journals and market power.” Journal of European Economic Association, 5 (2–3), 2007: 400–410.

- Dubois, P., M. Ivaldi., and A. Hernandez-Perez. “The market of academic journals: Evidence from data on French libraries.” Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(2–3), 2007: 390–399.

- Liu, L. G., and H. Gee. “Determining whether commercial publishers overcharge libraries for scholarly journals in the fields of science, technology, and medicine, with a semilogarithmic econometric model.” The Library Quarterly, 87 (2), 2017: 150–172.

- Morrison, H. “Global OA APCs (APC) 2010–2017: Major trends.” 2018. https://elpub.episciences.org/4604/pdf (accessed March 27, 2019).

- Nawata, K. “Estimation of the female labor supply models by Heckman’s two-step estimator and the maximum likelihood estimator.” Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 64 (3–4), 2004: 385–392.

- Petersen, H. C. “University libraries and pricing practices by publishers of scholarly journals.” Research in Higher Education, 31 (4), 1990: 307–314.

- Petersen, H. C. “The economics of economics journals: A statistical analysis of pricing practices by publishers.” College & Research Libraries, 53 (2), 1992: 176–181.

- Pinfield, S., J. Salter., and P. A. Bath. “A “gold-centric” implementation of open access: Hybrid journals, the “total cost of publication” and policy development in the UK and beyond.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 68 (9), 2017: 2248–2263.

- Shamash, K. “Article processing charges (APCs) and subscriptions: Monitoring open access costs.” 2016. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/reports/apcs-and-subscriptions (accessed August 10, 2018).

- Shulenburger, D. “Substituting article processing charges for subscription: The cure is worse than the disease.” Association of Research Libraries. 2016. http://www.arl.org/storage/documents/substituting-apcs-for-subscriptions-20july2016.pdf (accessed September 20, 2018).

- Siler, K. “Future challenges and opportunities in academic publishing.” Canadian Journal of Sociology, 42 (1), 2017: 83–114.

- Solomon, D. J., and B.-C. Björk. “Publication fees in open access publishing: Sources of funding and factors influencing choice of journal.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63 (1), 2012: 98–107.

- Wang, L. L., X. Z. Liu., and H. Fang. “Investigation of the degree to which articles supported by research grants are published in open access health and life sciences journals.” Scientometrics, 104 (2), 2015: 511–528.

- Wang, Y., and Y. Ge. “The effect of family property income on labor supply: Evidence from China.” International Review of Economics and Finance, 57, 2018: 114–121.

- Wooldridge, J. M. Introductory Econometrics. 2006, South-Western, Canada.

The classification of publishing countries into regions is based on the classification used in various government statistics, including World Statistics.

The mean and median APCs are calculated only for APC-funded journals in this study, because the journal decides whether to charge an APC.

The mean CiteScore2016 is calculated for all journals that belong to the group, because journals that are not indexed in Scopus have citations (including zero) below the criterion for including a title.

In this study, the Big 5’s open access journals are defined as journals published on the website of any of the Big 5 publishers. For example, although BMC (formerly Biomed Central) was an independent open access journal publisher, it is part of the Springer Nature Group at present. BMC journals have been published on the BMC website, not SpringerOpen, which is the website for Springer open access journals. Therefore, BMC journals are not included in the Big 5’s journals.

Since the DOAJ screens journals based on certain criteria, this study considers that open access journals that publish articles without a proper review process are not included in the samples.

Alperin (2014) found that the ratio of open access journals to overall online journals in South America is high and that many open access articles are published in local languages.

For sample selection bias and the model to solve the problem, see Wooldridge (2006).

Several journals discount the APCs for authors from low-income countries (as classified by the World Bank) based on the waiver policy.

Strictly speaking, the relationship between APCs and the number of articles should be justified using the number of articles submitted by authors, and not the number of articles published. However, information regarding the number of articles submitted by authors or the acceptance rate is not provided by most sampled journals.