Publish All the Things: The Life (and Death) of Electronic Literature

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Electronic literature, or e-lit, poses particular challenges for publishing, not only in terms of preservation but also in terms of editorial strategy and philosophy. Editorial praxis is driven by a simple question one must confront when working in e-lit publication: How does one publish and preserve a piece of complex multimedia work in a way that balances competing archival, scholarly, and creative needs? This article will explore some of the issues that editors must, sooner or later, face if they are to build and maintain a robust platform for works of both e-lit and media scholarship, using as an example the philosophies of one journal specializing in e-lit publication.

Introduction

Electronic literature, or e-lit, has rested fairly uneasily in the space between digital humanities (with its emphasis on tools and existing texts), creative writing (with its emphasis on textuality and code as a form for exploration), and art (with its emphasis on media formats and visual expression). In many ways e-lit stands in as a kind of boundary genre for publishing. On the one hand, we see a lively and thriving ecology of venues for e-lit performances and exhibits outside of a traditional, print-centric press structure – an ecology that prefers instead to use the art model of panel jurying and curation. On the other hand, the idea of publication as a way of disseminating and conferring status on a work of e-lit continues to be compelling for both creative writers, who wish their work to travel to an audience, and academics, who often must approach a work outside of its original context due to lack of access to galleries or festivals. Therefore, publication venues play an important role in the dissemination and preservation of e-lit.

The online journal of electronic literature Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures[1] began as a gallery section, curated by electronic poet Jason Nelson, of the online journal Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge.[2] Rhizomes has long provided an online, networked voice for (in particular) Deleuzian and other modes of scholarship that emphasize writing and thinking as a rhizomatic, rather than linear, activity. Edited from its very inception by Ellen E. Berry and Carol Siegel, Rhizomes provided a space for not just essays but also some provocative works of e-lit, including the original “Hyperrhiz” publications featuring works from some of the notable emerging practitioners in the nascent field: Jason Nelson, Steve Duffy, Thom Swiss,[3] Lewis LaCook, Marjorie Coverly Luesebrink, mIEKAL aND, Felt Bomar, Millie Niss, and Davin Heckman.[4] In 2005, Hyperrhiz spawned a whole new infrastructure, expanding into a separate-but-affiliated journal specializing in electronic literature, net art, and new media criticism. Thrust into the unfamiliar behind-the-scene processes of e-lit work, I found myself searching for an intellectual model for understanding what it is an editor might do when it comes to e-lit.

In this essay, I will attempt to tease out some of the issues that arise in the practice of editing electronic literature works for online publication. Like the works themselves, the process of e-lit publishing is often a kind of rhizomatic, rather than linear, practice: each work may deploy a wide variety of software tools, authorial and artistic philosophies, and technical presentational conventions, each of which may pop up in publication at unexpected moments. In explicating e-lit publication as a process that is iterative and rhizomatic, therefore, this essay will mirror that movement, passing variously through editorial approaches, technical considerations, archival issues, and engagement with the works themselves in a diffractive mode. This structure, I believe, more closely mirrors the actual workflow of e-lit publication, such as it is bound up in layering, repetition, revision, and rethinking the role of editor as preserver, curator, and critic in one.

Issues for editors working in e-lit

There are a number of publication venues working hard to publish on non-print-analog multimedia platforms (works in Scalar with ANVC/UC Press[5], the now retired Anvil Academic[6], Intermezzo[7]). In thinking about the kinds of works an academic press might publish digitally, however, presses often end up thinking primarily of critical or interpretive works that are digital and hypertextual, but still conform to traditional scholarly standards. Conversely, the terrain in publishing electronic literature is more uneasy, embodying a tension between the perfect code attempted by, for example, the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) and other metadata standards for works that are primarily archival, commercial, and institutional imperatives, and the (sometimes imperfect) coding of one-off, bespoke works that constitute what we think of as electronic literature. Editorial work at Hyperrhiz embodies that tension – on the one hand, preparing to maintain works for future viewers and scholars but on the other hand attempting to give them a space to be themselves.

While we usually consider the so-called platform as indicating a specific electronic tool or piece of hardware on which to build a media artifact, we forget that literary studies has long had its own complicated platform on which creative and scholarly communication is executed in a public space. Publishing is both an assemblage of hard and soft technologies, as well as a series of actions, decisions, reimaginings, and (sometimes) regrets – a process as platform. As a platform for writing (extending an analogy from the physical platform on which the speaker stands in the medieval town square), the enterprise of publication in all its variety of forms has been a kind of essential substrate for both creative writing and scholarship in the sense of both textual curation and public dissemination.

Editorial processes often mirror established rhetorical processes, for example homiletics, which can be defined as the study of the analysis, classification, preparation, composition, and delivery of sermons: an analogy that foregrounds the sacredness of the text, its inviolability. It is true that much of what an editor does is what Nick Montfort has called "refactoring" and "compression.”[8] But there is also a lot of synthesis work to be done. In any editorial process, the editor is tasked with selecting and remixing the work in a way that makes sense as an “issue.”

Editors of electronic literature must be sensitive to artists’ wishes to let projects be what they are while still making those projects the very best they can be. For scholarly editors, who are trained in workflow processes that are premised on revision, the problematic task of asking artists (as opposed to writers) to revise their media works for publication can be very tricky to navigate. Those authors who approach e-lit as text (often scholars from English departments) submit initial essays or code and tend to be more accustomed to revision, design editing, and open sourcing of materials. They have presumably been trained by the long scholarly tradition of “revise and resubmit” at the publication stage. This includes scholars working in critical code studies and “code as text” creative writers.

Those who approach e-lit as visual or multimedia art, in contrast, are more likely to submit works as finished products and are more concerned with preserving the design vision and protecting files and images. This may have to do with the more problematic issue of licensing visual material than text (“fair use” is certainly trickier) and the more pronounced tendency to use complicated software packages necessary for producing visual or sound work, which often produce binaries that are not easily editable or shared. In addition, visual/media art is usually exhibited (as a finished, singular item and event) rather than published (with all the editorial workflows and assumptions of revision that entails).

This split represents an interesting problem for a publisher trying to work in the interstices of these two quite distinct cultures, especially as a scholar who herself comes from an English-trained background and is specifically interested in the open source dissemination of software and the remixing of work by new generations of artists and writers. In some ways, it reflects a similar split to those within English departments between traditional literary scholars (who are interested in writing as a form that is structural to meaning) and scholars of rhetoric and composition (who are interested in writing as a practice that is structural to meaning). In terms of the aesthetics of a work, literary scholars, like artists, view writing as having a fixed aesthetic integral to the works themselves, whereas rhetoric/composition scholars view writing as a process and are more likely to view revision and remix as part of the “life” of a text. A fixed vs. processual understanding of what a work is, similarly, expresses itself variously, but consistently, in the publication process for e-lit works and e-lit scholarship, with works being deployed along a continuum from finished, flattened non-editable file to downloadable, remixable code.

Death (of the text)

A pressing concern in this endeavor is preservation of the works themselves. The Electronic Literature Organization’s canonical Acid-Free Bits[9] issued this mandate early, in 2004, arguing that electronic works, which are ephemeral in nature because of the constant turnover of software and hardware, urgently need to be preserved. The suggestions in the pamphlet are wide-ranging: to preserve working, antique platforms with each work (e.g., at one ELO symposium, the “door prize” was an early, working Mac, now practically an antique, with a full complement of software and creative titles); to try and convert the works into a standards-compliant, future-proofed format insofar as we can; to provide emulation platforms for works; to provide access to original source files; and the lowest-tech, most enduring suggestion, that exhaustive documentation (not just recording, but also description – perhaps you could call it ekphrasis) might be the only way to ultimately preserve pieces that inevitably decay.

A complicating factor is that sometimes a work genuinely wants to disappear. William Gibson’s Agrippa (1992), the book that destroyed itself, is a prime example. Agrippa is a work built to die through processes of code erasure and exposure of photosensitive ink to light. Certainly there is something attractive about the ephemeral/instant erasing of a new media project by itself, but also interesting is that despite the death of the work its documentation can be so enduring. As Matthew Kirschenbaum argues,

Despite its being a uniquely volatile electronic object – its own internal mechanisms radically ephemeral by both intent and design. “Agrippa” has proven remarkably persistent and durable over the years. No model of digital textuality that rests upon the new medium's supposedly radically unstable ontology can be taken seriously so long as countless copies of this particular text remain only a search query away.[10]

As Kirschenbaum notes, Agrippa has had an advantage in that some of its components remain online. Some works are more resistant, especially when they are comprised of material, rather than textual, components. But even then, they can have a surprisingly robust afterlife. Take as an example Swiss artist Jean Tinguely’s work “Homage to New York.” Tinguely was asked in 1960 to produce a work to be performed in the Sculpture Garden of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Working with Billy Klüver and Robert Rauschenberg, Tinguely assembled a 27-foot machine that would systematically dismantle itself, calling it a “self-constructing and self-destroying work of art.”[11] Over the course of a half hour, the machine tore itself apart while playing a commentary on its own life and death (MoMA notes that the exhibit included “a recording of the artist explaining his work, and a competing shrill voice correcting him”[12]). Nevertheless, even though the work was designed to self-erase, the viewing public rescued some pieces; MoMA itself preserved a portion and titled it “Fragment from Homage to New York,” granting the work a new permanent life as a fragment.

Fully electronic works can similarly be designed to die and yet still leave traces. Some traces are accidental or the work of dedicated preservationists, but some are left behind as part of the life plan for the work itself. Consider, for example, Ian Bogost’s 2011 Facebook game known as the Cow ClickARG, a member of the family of games known widely as “clicker games.” Initially the conceit was simple: a field of cows that players could click on, causing the cow to moo (and earn a point for its clicker). The clicking, however, soon took on a sinister (and somewhat desperate) role, that is, preventing an impending “Cowpocalypse” by repeatedly clicking to extend the cows’ time.

After the Cowpocalypse of September 7, 2011, the game continued in its own eerie afterlife. In an audio interview with P. J. Vogt in November of that year, Bogost reflected on the refusal of players to let the game go:

Clearly electronic life and death is, if not negotiable, at the very least a porous boundary.

Beyond preservation

Works such as “Cow ClickARG” or Agrippa point to a double preservation need. On the one hand, saving the object itself allows for that object to be studied directly by future scholars. On the other hand, what can be lost is the original experience of interacting with the object itself – including the experience of watching a Cowpocalypse and wandering through the empty fields of its aftermath. Sometimes, then, it is better to compare media works not with print texts but with performative art pieces or oral works. Examples of embodied “writing” can illustrate the disappearance of creative writing and/or critique through performance: for example, Marcel O’Gorman’s DREADmill (2006–2007) or Dene Grigar’s Rhapsody Room (2007–2008). Because each is a performance, the works disappear as they are displayed – more like performance/oral tradition works than writing. Similarly, electronic literature, even if its aim is not to erase itself, has problems beyond merely documenting the objects themselves. Much electronic literature is what we would call “run-time experience,” so that the act of interacting with a work is an integral part of the work itself. Some of this performance is preserved in various recorded play-throughs or “traversals” that have appeared over the years. Dene Grigar and Stuart Moulthrop have been trying to address this problem more systematically for e-lit with their Pathfinders project, in which they record users interacting with the works in their original formats and on period-specific machines.[14]

But scholarly engagement (should) also go beyond preservation, whether that be archiving source code or playing through a work. E-lit often complicates our understanding of how it is we come to interact with a piece of literature in an analytical or critical mode, because e-lit is a combination of multiple media, performance, algorithm, and the form of publication it takes when released to the public can profoundly affect how we approach e-lit critically. As editors who are also scholars, thus, we must be concerned not just with preservation or interaction but also with ongoing, lively scholarly engagement with works of e-lit. Preservation is the precondition for this engagement, but how we go about it will inevitably affect the kind of critical unpacking we can do. Can we approach e-lit works not only as items to be preserved but also as items to unravel?

What lies beneath: what you can do with access to source files

It is clear that specific choices in the publication process might aid in (or hinder) the act of critique. Having access to original source files, for example, allows not only for potential preservation but also for scholars to do things with a work of e-lit they could not otherwise. One of the more difficult issues with reading electronic literature – particularly hypertexts – is that a reader can only see one part of the whole at a time. Hypertexts, for example, are usually made up of single-frame lexia (blocks of text). Asking readers to work through a hypertext story, whether it be plain HTML (i.e., pre-formatted text) or executed server-side (i.e., generated when clicked, by the server), gives them the sense that there is always more there, but that they cannot see it or map it holistically. Various tools have attempted to solve this problem: the venerable Storyspace[15] used boxes and lines, forming a visual web; the Literatronic engine[16] offers a partial solution with percentile mappings; and even the plain old web has the sitemap to fall back on. Ted Nelson’s long-delayed Xanadu project[17] promised a visually rich mapping of documents in a way that emphasizes how they are linked and how deep the web goes. But more often we are left working with pieces of literature that feel like they are hiding something from us.

N. Katherine Hayles notes that code has a tendency to operate through “concealing and revealing,”[18] in which the programmer chooses which code to leave visible for the purposes of authoring and debugging. Critics attempt to reveal code by stripping down the text, looking for what is there and, just as importantly, what is not, whether intentionally or unintentionally. Critics are the great debuggers or, at the very least, the great beta testers. This practice is also one that underlies the process of teaching, attempting to reveal what is concealed, to show how something is put together and to read what it says. Clearly, then, our interests as readers of electronic literature and as critics of electronic literature coincide: we want to get in under the hood and see what is going on.

The impulse to get inside a work of e-lit and dig around is not confined to readers and critics. Publishers, too, are naturally drawn to the making of a thing by dint of their own making practices while also being tasked with finding ways to disseminate their work in a way that is most accessible to readers and scholars. As Alan Kay said, “the ability to ‘read’ a medium means you can access materials and tools created by others. The ability to ‘write’ in a medium means you can generate materials and tools for others. You must have both to be literate.”[19] The question is, once we do get under the hood, what do we do there?

One useful conceptual tool in thinking about e-lit is the figure of the layer. Just as the platform forms the computational basis of software development, on top of which various strata of soft and hard technologies and practices are stacked to create a final product, so too we can think of works of e-lit as being built in layers of image, code, executable, etc. Software engineers have long understood the need to define how programs are put together not just in terms of memory management and calculation but also in terms of logical operations. Edsger Dijkstra's early work in structured programming aimed to describe what was happening in software engineering in a systematic way – looking at how code works as a series of building blocks. All programs, he argued, can be structured as

- sequences of instructions (“concatenation”)

- branches (“selection”)

- loops (“repetition”)[20]

all of which led to various combinations of modules (executable subroutines or functions). We see all these routinely in e-lit, but we also see something else: the idea of the “layer” (which might be more generally thought of as a metaphor for concurrency, multiple operations happening at once).

Layers are a standard metaphor in visual authoring environments. They have been called, variously, tracks (referring to the now old-school sound mixing booth and tape technology) and channels (referencing the separation of simultaneous frequencies). In visual programs such as Photoshop, they owe something to the old technique of layering overhead transparencies or viewgraphs. Sound engineers, similarly, have long known the usefulness of the layering metaphor, as have students of music. Tuvan throat singing, for example, is often referred to as layered, a reference to the multiple frequencies that are being generated simultaneously by a single voice. The layer operates not on linear, one-thing-at-a-time logic but on pizza logic: on the surface, we think we are experiencing a whole song, but what we are really experiencing is multiple strata, all executing at the same moment.

Computers were built on the notion of time-sharing, that is, even if multiple operations are being performed at the same time, the processor is splitting its time between instructions. The layer, though, has come to be a useful metaphor for understanding how multiple modules, branches, or sequences might be combined to produce a complex “stack” of objects, images, texts, computations. The layer is a powerful metaphor for building interactive works because it allows us to break up a poem, video, sound, or series of images into objects that can be edited separately but played concurrently. Thus, although a layer is, practically, a spatial (visual) metaphor, it is also useful for organizing time. The layer signifies time; specifically, it signifies simultaneity. A layer is consequential because it allows us to think about the ways space and time get reconfigured in e-lit built-in authoring systems that rely on layering technologies to achieve the desired effect of the author.

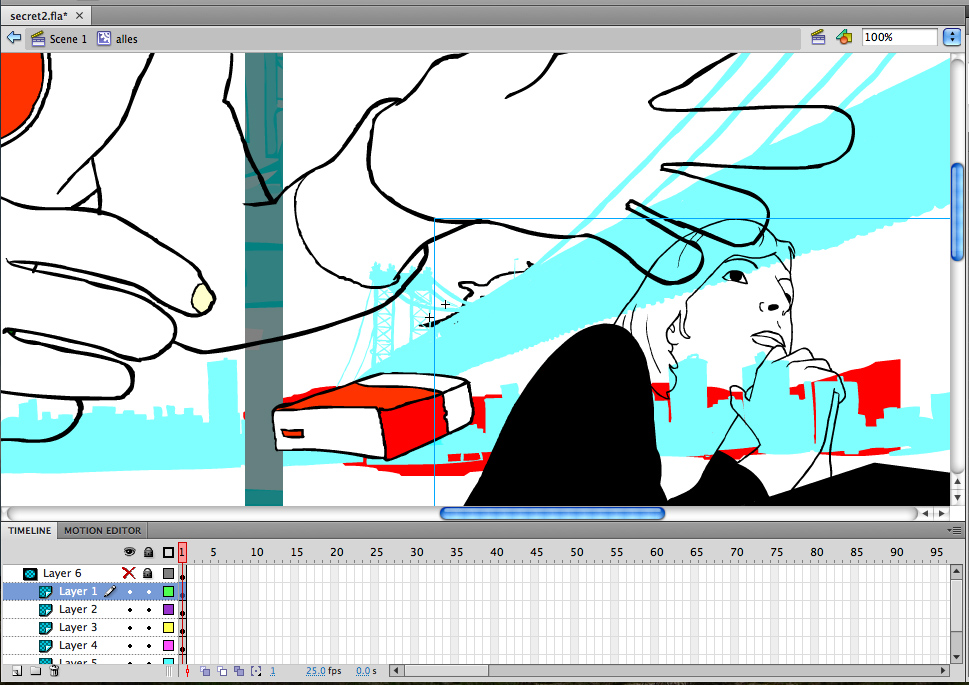

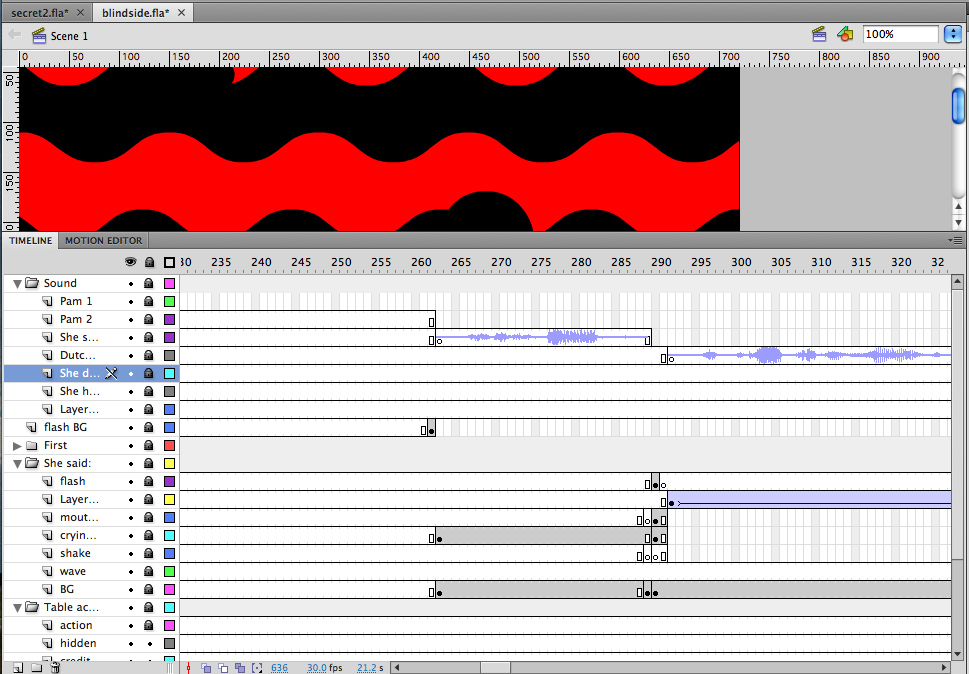

Figure 1: Adobe Flash interface showing layers. Each horizontal “row” represents a unique media asset (an image or sound file). These files are stacked atop one another. As the animation commences, a “playback head” passes through the rows (which represent a fraction of a second each) from left to right.[21]

Figure 1: Adobe Flash interface showing layers. Each horizontal “row” represents a unique media asset (an image or sound file). These files are stacked atop one another. As the animation commences, a “playback head” passes through the rows (which represent a fraction of a second each) from left to right.[21]David Shepard has used the terminology to talk about the conceptual layers that define any instance of electronic literature:

Generally, we may think of three different layers at which a digital work can signify; these may be permeable but these three terms provide a useful entry point for thinking about a work. The executed layer is the work experienced in the browser window, and the process that drives it; it is not only visual and auditory experience, but also the work’s process as it is experienced. Underlying the executed layer is the source code, the original text created by the author. Between these two layers is the execution of the code, based on the language structure.[22]

The execution of the code is affected by the language structure, Shepard says – that is, what language you use determines what you can do.

This is all true, but there is often also another layer sandwiched in there: the authoring layer. Many people working in electronic literature – Marjorie Coverly Luesebrink writing as M. D. Coverly, Serge Bouchardon, Victoria Welby, Jason Nelson, to name a few – have long worked not at the code layer or even the language layer but in a graphical user interface (GUI) authoring environment such as Director or Flash. These GUI systems fit in between the computer language they were coded in and the end product, and their available features will determine to some extent what we can do. All these layers are recognizable by their level of access, from end user at one extreme to machine at the other. So we see a hierarchy of readability forming:

- Executed Layer: visible to the end user/player/reader

- Authoring Layer: visible to the person using the authoring software

- Language Layer: visible to the coder producing the authoring software

- Source Layer: visible to the machine

Now ironically, and just to prove how conceptually recursive electronic literature is, in many cases the authoring layer consists of software that itself uses the metaphor of layer to help visually guide the author in the creation of a piece. This is true of many visual authoring systems, notably the Adobe Flash, Illustrator, and Photoshop family and virtually all sound editing software. These kinds of functional layers can become a crucial metaphor in the act of authoring.

E-lit in hiding (the pleasures of editing)

As a publisher, I have come to appreciate the affordances layers provide in looking at a piece of e-lit. Seeing through to the underneath helps me understand more fully how the work is constructed and, thus, perhaps how to more carefully preserve (as an archivist) and interrogate (as a critic) it. Let us consider two works published in Hyperrhiz for which I have a particular affinity when it comes to layers: Sandy Baldwin’s Goo (2006)[23] and Thom Swiss’s Blind Side of a Secret (2008). [24]

In my capacity as an editor of e-lit, I find Blind Side of a Secret and Goo to be perhaps my favorite works of all the many works I have edited in the last 10 years, and I have previously written about Blind Side with the primary author, Thom Swiss, in an article about remix and participatory culture. One of the reasons I value both Blind Side and Goo is that I have the source files for the works, as well as their finished pieces. Having access to those files has allowed me to look under the hood in both works, work through the layers, and make discoveries that I would otherwise have missed.

Blind Side of a Secret, originally published in Hyperrhiz in 2007, consists of three alternative iterations, each remixing a piece of writing by A. L. Kennedy on the subject of secrets.[25] The first is a traditional time-based Flash piece that “plays” through to the end without interaction. The second iteration is a QuickTime movie that similarly plays like a music video. The third iteration, which Swiss and I have previously referred to a “Blind Side Nils” after Swiss’s collaborator on the piece, transforms Kennedy’s original work into a Flash animated clickable poem in visual form. Looking under the hood at the authoring layer, it is a nicely modular poem, with the FLA file working thus:

- “Open Project” launches movie clip “blind.”

- The playback head moves to frame 30 and waits. If the “close” button is hit (a trigger point), it moves on to frame 31 and closes the movie. Otherwise it just sits there.

- In frame 30, we have many layers, including layer 6, which is a composite sub-movie “alles.”

- If we click on “alles,” we see that this sub-movie consists of one frame only, with multiple layers. Each layer is a separate movie.

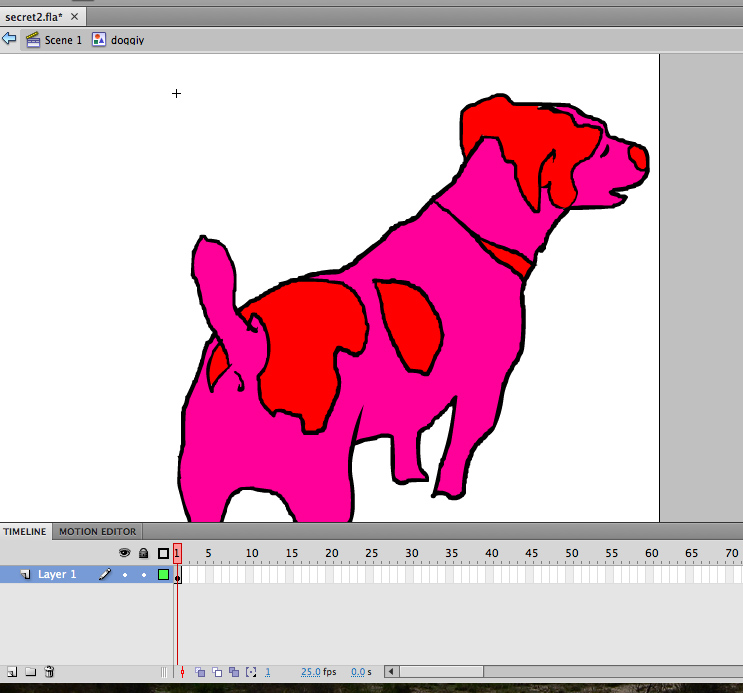

- Clicking on any individual layer will trigger its action, for example clicking on the object in layer three will trigger the sub-movie “aotogaan.”

In a nice little joke, Nils has provided us with an Easter egg: a “doggiy” cast member (an illustration of a dog) that appears to play nowhere in the final product. There are two possibilities here, both having to do with time. First, perhaps Nils put it there intentionally as a joke, in which case the doggiy gets no time on the stage; he exists only in the library and not on the timeline. The second is that the doggiy is an artifact from a deleted piece of the poem, in which case it signifies the lost past of the authoring process.

Without the layered Flash files, we can only view the final piece and try to interpolate how it is structured by identifying trigger points and repetitions. Having no access to the authoring layer, we cannot see the whole potentiality of a piece, only a single run-time iteration. Indeed, the whole joy of discovering an Easter egg such as the doggiy hidden in the back end is gone; the multi-channel mix is replaced by the single-channel “mux” (a borrowed electronics expression for the process in which multiple channels of sound are compressed into a single feed, an action akin to exporting a Flash file and thereby collapsing all the layers into one).

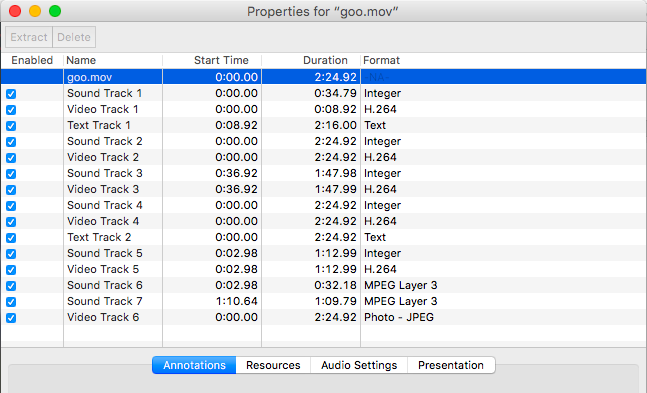

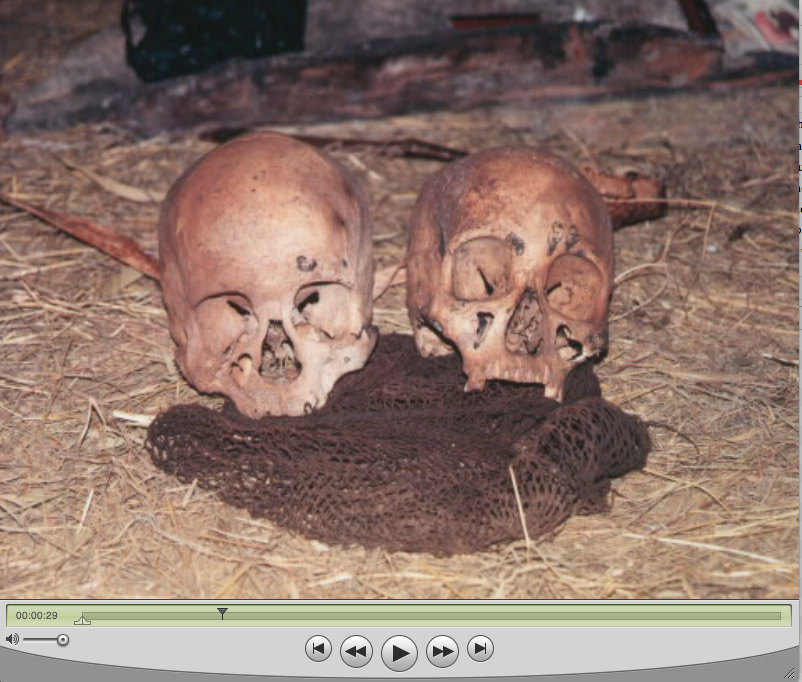

A second example of the benefit of having access to source files is Sandy Baldwin’s QuickTime movie Goo (2006). At first sight looking like a recording of video game play-through, this two-minute-twenty-four-second piece features multiple layers consisting of two text tracks, seven sound tracks, and six video tracks, with the text describing Indonesian atrocities in Sumatra and Papua New Guinea. At the very “bottom of the stack” of tracks lies “Video Track 6”: a single-frame JPEG image of two human skulls lying on top of a net on a ground of dirt and straw.

Without the layered version of the video, that track would not be visible, and indeed the only reason I noticed it was because, in resizing the video for compressed streaming, I was forced to resize individual layers of different heights. This gave me the opportunity to flip through the layers, switching on and off between different strata playing simultaneously. As a scholar of the hidden, this piece reminds me of Hans Holbein the Younger’s painting The Ambassadors (1533), in which a skull is present, painted in the floor of the work, but can be viewed only if you turn the painting almost side-on. Pointing to Jacques Lacan’s reading in The Four Fundamentals of Psychoanalysis (1973) of the painting, Slavoj Žižek notes that this is the act of “looking awry,” showing that the only way you can confront death is by turning everything else sideways so that it becomes unrecognizable. Thus “the ground of the established, familiar signification opens up; we find ourselves in a realm of total ambiguity, but this very lack propels us to produce ever new ‘hidden meanings'’: it is a driving force of endless compulsion.”[26] The act of turning off QuickTime layers in Goo is the same kind of moment. In order to see the underneath layers you must change your depth perspective, in this case by removing obscuring images to reveal what lies hidden beneath. In doing so, a compulsion is revealed: to look at and look through, to dig for the “secret” of a work. This is a compulsion editors feel, and one we feel compelled to share.

Kits as an alternative preservation strategy

Having had privileged access (as the editor) to source files has forced me to consider my role in enabling (or constraining) e-lit scholarship. How should my platform-of-practices be revised to encourage these kinds of “deep reads”? What kinds of things (not just papers, or even multimedia works) could we publish if we had access to source files or even privileged source files as a means of publication? In working through such a question, I have found Craig Saper’s adaptation of the digital humanities “tent metaphor” very useful. Saper’s tents look something like this:

- Small tent: TEI, working with manuscripts and archives, digitizing, primarily archival work, and the oldest part of the field.

- Big tent: the more recent understanding of digital humanities (DH) as incorporating data and text mining, visualization, electronic scholarship, and editorial work.

- Circus tent: overlaps with art installations, critical making, experiments with electronics.

If we follow Saper’s model, e-lit editorial processes encompass both small tent (encoding work for publication) and big tent (building an infrastructure for other e-lit and DH scholars to exhibit and publish). And over time, Hyperrhiz has expanded to become not just an electronic journal that combines critical and creative works but also the “circus tent”: para-academic writing, physical computing, and 3D alternatives and complements to texts.

We know, also, that the scientific community has models and practices that might prove useful – notably, the sharing of data. One possible model is the one we see developed in open source repositories (such as GitHub). As humanists on the outside of the STEM phenomenon looking in, we are accustomed to the idea in the academy that computer science has it all sewn up with large, monetizable big data projects that secure multimillion dollar grant funding. In our less charitable moments, we resent it. But there is another side to CS – the world of small data and small tools. Open source repositories provide a house for software projects to live (as an archive) but also to thrive, to be forked, updated, merged.

The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and other funding agencies now routinely require DH projects to have a “data management strategy” that follows the repository model, with software tools developed in the course of a project being maintained in a public space. E-lit has sometimes similarly flirted with sharing and remixing (consider, e.g., the fertile ground for numerous authors created by Montfort’s release of Taroko Gorge [2009–2016]),[27] although it is usually more the case that e-lit practitioners release an authoring system for download, such as Daniel Howe’s RiTa, rather than an actual work itself. With a few exceptions such as Taroko Gorge, e-lit often continues to be presented as the end product of an authoring/artistic process rather than as a piece of work in the act of becoming.

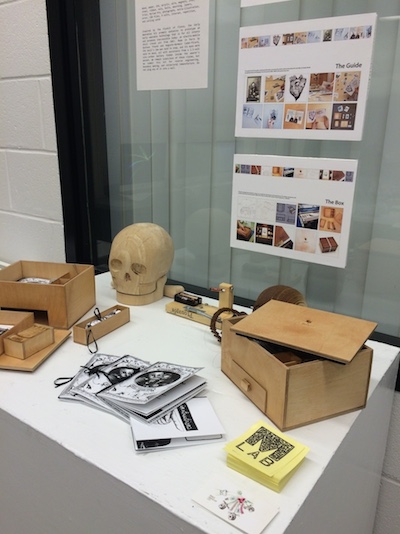

As an experiment, colleague David Rieder and I ran a special issue of Hyperrhiz in 2015 in which we published objects and processes as well as texts. Issue 13 of Hyperrhiz, “Kits, Plans and Schematics,” features works that answered the call for “executable culture”: downloadable code and recipes/sets of instructions for reconstitution of the work itself. Two particular works express the complex and creative affordances of such a structure. The first is “Manifest Data: A Kit to Create Personal Digital Data-Based Sculptures,” by the Duke S-1 Speculative Sensation Lab.[28] This work records and translates network activity into a 3D-printable shape that is then placed in the face of a garden gnome, the traditional protector of domestic space. Manifest Data is made up of multiple components, including code for a TCP/IP network activity sniffer, 3D printer schematics, painted canvases, all of which may be reconstituted by the end user to form personalized 3D printed blobs (visualizing network activity) smooshed into the front of a series of concrete garden gnomes.

Figure 7: “Manifest Data” gnomes and augmented reality artefacts on display, Rutgers-Camden Digital Studies Center, October 14, 2015. Exhibit curated by Jim Brown and Robert Emmons.

Figure 7: “Manifest Data” gnomes and augmented reality artefacts on display, Rutgers-Camden Digital Studies Center, October 14, 2015. Exhibit curated by Jim Brown and Robert Emmons.The second is Jentery Sayers’s MLab “Kits for Cultural History,” consisting of an “Early Wearables” kit which features downloadable files and instructions for reproducing a laser-cut and 3D printed kitset that can assemble a battery-powered version of a Victorian stick pin.[29] Part of the University of Victoria Maker Lab in the Humanities series of “kits for culture,” Sayers and colleagues draw their inspiration from the Fluxus kit art movement of the 1960s, providing a kind of reassembling of existing elements that privileges both cultural exploration and the process of “making.”

Figure 8: Early Wearable kit on display at the Rutgers-Camden Digital Studies Center, October 2015. Exhibit curated by Jim Brown and Robert Emmons.

Figure 8: Early Wearable kit on display at the Rutgers-Camden Digital Studies Center, October 2015. Exhibit curated by Jim Brown and Robert Emmons.Both of these projects play on something that is inherent to digital culture but also a longstanding part of material culture: the ability to reproduce a unique object by using instructions (like a cooking recipe) and open-access downloadable components (like 3D files). The object itself is not “publishable” in the traditional sense, but it is “reproducible” in a way that extends the idea of print. Along the way, the original object might die, but we have a robust infrastructure for reconstructing it or, at the very least, source files that are human-readable.

What now?

Given the competing needs enumerated above, electronic editing in the field of e-lit research is clearly a complicated venture. We must face a balance of concerns including preservation versus allowing a work to “die” and the need of the scholar to have access to source files versus the need of the artist to preserve their work’s integrity. But one more need must be acknowledged: our own uneasy position as authors, artists, and editors in the academy today.

When I first started graduate school, back in the mid-1990s, I was introduced to Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto” (1984) and for a long time it was my touchstone. Haraway saw both the possibilities for cyborgs (which is what she is known for) but also the potential downsides, in the form of co-option (both physically and ideology) by the military-industrial complex. Think how this has played out in the case of drones, for example, which are a cyborg assemblage. In 1995 Tim Luke was already sounding the other alarm, what he called the “digital dehumanities,”[30] in which computation allowed for not just military but commercial applications in surveillance and automation. Think neoliberalism’s emphasis on big data but also Benjamin Bratton’s recent provocation: a future in which drones pick fruit in the United States, but their pilots are in countries with lax labor standards and low wages.[31] In the academy, we have our own version of these bad cyborgs: powerful institutional forces that demand somewhat arbitrary peer review standards that may seem “blind” but are often more about preserving status hierarchies or work that is primarily critical and not creative or experimental, enabled by academic presses who are figuratively pressed by the demands of falling funding from their own institutions and the shifting requirements of granting agencies.

One model for thinking about this problem is the work of Eileen Joy and Punctum Books, which publishes print-on-demand monographs by academic and para-academic writers. Joy thinks of publishing in a very different way, characterizing it both as the “pressing” of work in a traditional sense (creating an object that can be completed and circulated) but also as what she calls “the pressing ‘crush’ of the crowd into the commons.” She continues, “The university – and the presses associated with it – will hopefully continue to serve as one important site for the cultivation of thought and cultural studies more broadly, but increasingly their spaces are striated by so many checkpoints and watchtowers.”[32] Para-academic publishing should thus try to balance the needs of professional scholars and those outside the regularizing spaces of the academy: independent scholars, public writers, artists. It should provide a space for academics to publish with the imprimatur of peer review while simultaneously recognizing that the metrics-obsessed gateway of institutional affiliation should not be a bar to entry for artists, who exist in quite a different evaluative ecology. In particular, all academics, para-academics, and artists should have access to some of the more useful tools academe has developed: peer review feedback, robust indexing, and archiving in repositories.

If there is any editorial philosophy statement to be made on behalf of e-lit publishing, it is this: Preserve where we can. Document where we cannot. But in all cases, keep engagement at the forefront of our processes. We should try to extend what it means to publish while retaining an infrastructure that supports authors: continue to publish screen-based e-lit and traditional criticism but also house small and large-scale creative and critical works that may be made up of multiple physical, textual, and digital components. At the same time, we should do our best to preserve works for the future through a combination of scholarly indexing, documentation, source file duplication, and sharing of works for remix. In this work, we have to deal with striking a balance between the desire to preserve a work in its own right and the desire to make sure it can be true to its own exigency, to be reworked, documented, or just plain die, and leave behind an empty space like Bogost’s Cow ClickARG. Our mission is thus, in part, to do what Eileen Joy calls “standing up for bastards.” We must take care of artefacts and source files where we can but also act as a welcomer at the door of the oubliette, providing a space for works (if they so desire) to walk through to the afterlife with grace.

Helen J Burgess is Associate Professor of English at North Carolina State University, and editor of Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, a peer-reviewed journal of electronic literature and new media scholarship. She is a member of the Board of Directors of the Electronic Literature Organization.

Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, https://doi.org/10.20415/hyp/.

Rhizomes: Cultural Studies of Emerging Knowledge, https://doi.org/10.20415/rhiz/.

Jason Nelson, Thom Swiss, and Steve Duffy, “Hyperrhiz,” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies of Emerging Knowledge Issue 3 (2001), http://www.rhizomes.net/issue3/hyperrhiz.html.

Jason Nelson, Lewis LaCook, Marjorie Coverly Luesebrink, mIEKAL aND, Felt Bomar, Millie Niss, and Davin Heckman, “Hyperrhiz 2,” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies of Emerging Knowledge, issue 5 (2005), http://www.rhizomes.net/issue5/hyperrhiz2/hyperrhiz2.html.

Alliance for Networking Visual Culture, Scalar, https://scalar.me/anvc/.

NITLE/Brown Foundation, Anvil Academic, http://anvilacademic.org/.

Nick Montfort, “Imaginative, Aesthetic, Executable Writing,” in Codework: Exploring Relations Between Creative Writing Practices and Software Engineering, NSF Workshop, Morgantown, WV, April 2008, http://www.clc.wvu.edu/r/download/19664.

N. Montfort, and N. Wardrip-Fruin, Acid-Free Bits: Recommendations for Long-Lasting Electronic Literature from the ELO's Preservation, Archiving, and Dissemination (PAD) Project (Los Angeles, CA: Electronic Literature Organization, 2004).

Matthew Kirschenbaum, Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008), 239.

Museum of Modern Art, “Homage to New York: A Self-Constructing and Self-Destroying Work of Art Conceived and Built by Jean Tinguely,” MoMA exhibition website, 1960, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3369?locale=en.

Museum of Modern Art, “Jean Tinguely, Fragment from Homage to New York, 1960,” MoMA, catalog entry, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81174?locale=en.

National Public Radio, All Things Considered, November 18, 2011, http://home.utah.edu/~klm6/3905/cow_clicker_npr.html.

Dene Grigar and Stuart Moulthrop, Pathfinders: Documenting the Experience of Early Digital Literature, University of Southern California: Alliance for Networking Visual Culture, 2015, http://scalar.usc.edu/works/pathfinders/index.

Eastgate Systems, Storyspace, http://eastgate.com/storyspace/.

Juan Gutierrez, Literatronic: Adaptive Digital Narrative, http://www.literatronica.com/src/initium.aspx.

N. Katherine Hayles, My Mother Was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 54.

Alan Kay, “User Interface: A Personal View,” in Multimedia from Wagner to Virtual Reality, edited by R. Packer and K. Jordan, 121–131 (W.W. Norton & Co., 2001), 125.

Edsger W. Dijkstra, “Notes on Structured Programming,” Technological University Eindhoven Department of Mathematics, 1970, http://www.cs.utexas.edu/users/EWD/ewd02xx/EWD249.PDF.

Back end of Flash file used to produce Thom Swiss, Blind Side of a Secret, Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, issue 4, https://doi.org/10.20415/hyp/004.g03.

David Shepard, “Finding and Evaluating the Code,” in N. Katherine Hayles, Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary, companion website resource, http://newhorizons.eliterature.org/essay.php@id=12.html.

Sandy Baldwin, Goo/The Lincolnshire Poacher, Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, issue 2 (2006), https://doi.org/10.20415/hyp/002.g02.

Thom Swiss, Blind Side of a Secret, Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, issue 4 (2008), https://doi.org/10.20415/hyp/004.g03

A. L. Kennedy, So I Am Glad: A Novel (New York: Vintage Books, 2001), 22.

Slavoj Žižek, Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture (Cambridge, MA: October Books, 1991), 72.

Nick Montfort, et al., Taroko Gorge, Electronic Literature Collection Vol. 3 (2009–2016), Electronic Literature Organization, http://collection.eliterature.org/3/collection-taroko.html.

Duke University S-1 Speculative Sensations Lab, “Manifest Data: A Kit to Create Personal Digital Data-Based Sculptures,” Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, issue 13 (2015), https://doi.org/10.20415/hyp/013.s03.

Jentery Sayers et al., “Kits for Cultural History,” Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, issue 13 (2015), https://doi.org/10.20415/hyp/013.w02.

Tim Luke, Communications graduate seminar, Victoria University of Wellington, 1995.

Benjamin Bratton, “Designing on Behalf of Emergencies: Integral Accidents of Planetary-Scale Computing,” plenary talk, Babel on the Beach: 3rd Biennial Meeting of the Babel Working Group, University of California, Santa Barbara, October 16, 2014.

Eileen Joy, “Spontaneous Acts of Scholarly Combustion,” Lateral: Journal of the Cultural Studies Association, issue 3 (2014), http://csalateral.org/issue3/universities-in-question/joy.