Social Media: New Editing Tools or Weapons of Mass Distraction?

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

This paper was refereed by the Journal of Electronic Publishing’s peer reviewers.

Abstract

Despite the exponential rise of social media use in the publishing industry, very little is known about its impact on the editing profession. The aim of this paper is to investigate how editors and proofreaders use social media tools in their work. The first part is a descriptive study of users and uses of social media in the context of editing. The second part critically evaluates the positive and negative aspects of using social media tools for work and explores practical implications. The results of a survey of 330 editors and proofreaders indicate that the use of social media tools is motivated chiefly by the interpersonal utility and information-seeking behavior. While social media tools are seen as easy to use, their perceived usefulness varies. Moreover, they are considered to be time consuming and distractive. Other concerns, and indeed barriers to the adoption of social media, are linked with the blending of professional and private identity, the merging of working and personal life, and issues surrounding privacy and author’s confidentiality.

Introduction

There is little doubt that “social media is embedding itself” in our society and changing the way we live, learn, and work. Requiring little or no technical expertise, social media is redefining roles within the publishing industry, allowing publishers and authors to reach and engage with readers directly. With more than 850 million active users on Facebook and more than 50 percent of them logging on in any given day,[2] it is not surprising that authors, publishers, and booksellers explore social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms, to connect with readers.

While the use of social media by publishers, booksellers, and authors has been the subject of many blog posts and magazine articles,[3] it has attracted only a modest amount of research so far,[4] none of which has investigated whether using social media tools is worthwhile and effective for editors and proofreaders.

Editors and proofreaders are accustomed to keeping up with ever-changing computer-based technologies. Digital technologies have been transforming the way books are written and published ever since computers, the Internet, and email were first introduced in the early 1990s. Since the late 1990s, when Microsoft Word’s track changes, macros, and other functions revolutionized the way books were edited, workflow technologies continue to expand and nowadays editors are no strangers to design, formatting, and web authoring software.[5]

Digital publishing workflows are said to promote “higher editorial accuracy, higher production standards and greater cost and time efficiencies,” but at the same time they have expanded editors’ responsibilities and increased the risk of professional isolation.[6] These changes, combined with the increase in outsourcing and casualization of editing tasks, mean that editors and proofreaders must “more than ever be aware of their professional attributes and capabilities, adaptable to changing work contexts, and proactive in managing and marketing their expertise.”[7] Now the question is whether they should add social media to the list of their skills.

What is social media?

Social media “is the current iteration of internet, with user generated content, semantic storage, APIs and far improved parse ability via XML/JSON and the community of users as an asset.”[8] Using non-technical language, social media can be described the “way people share ideas, content, thoughts, and relationships online.”[9] The term “social media” is used here to describe the phenomenon, while “social media tools” refers to the technologies.

Social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn, Google+) are one of six types of social media tools identified by Kaplan and Haenlein on the basis of the degree of self-presentation and self-disclosure required, the degree of intimacy and the immediacy of the medium, and finally the amount and the type of information that can be transmitted in a given time (described as media richness). The remaining five categories include collaborative projects (e.g., Wikipedia, Google Docs), blogs and micro-blogs (e.g., WordPress, Blogger, Twitter), content communities (e.g., YouTube), virtual game worlds (e.g., World of Warcraft), and virtual social worlds (e.g., Second Life).[10]

The degree of engagement and participation, and subsequently of influence in social media, varies. Katie Paine distinguished five types of information consumers with differing levels of online engagement—from passive “searchers” who tend to ignore social media, to “lurkers” who follow but do not contribute, to “casuals” who participate infrequently, to “actives” who participate on a regular basis, to “defenders,”[11] who could also be described as “influencers” in a non-commercial context, who frequently post comments, write blogs, edit wikis, and exert a high degree of authority in their networks. Active users are also known as “produsers”—a term coined by Axel Bruns to indicate “users as well as producers of information and knowledge.”[12]

The blending of barriers between users and producers of content, between private and public persona, between working and personal life—which is emblematic of social media—is changing the way the publishing industry, and society in general, operates. Although the anecdotal opposition to social media can be very strong, in reality there is no escaping it. The transformation of a traditional “searchable” web into a connected, “social” web is well underway. “Social networks are now used by 90 percent of U.S. Internet users—for an average of more than four hours a month,” and the consumption of social media is growing at the cost of non-social web.[13]

While the level of participation in social media can differ, a clear understanding of the capabilities of social media tools is essential for editing professionals, especially as they operate in an industry that is driven by content production and has a lot to both gain and lose from this transformation.

This paper analyzes how editors and proofreaders use social media in the context of their work and professional development. The specific objectives are to examine the characteristics of social media users and the uses of social media tools at work, and to evaluate the drivers, benefits, and barriers of social media use. Additionally, the practical implications of using social media in the work context are explored.

Theories and framework

Simone Murray describes the interdisciplinary character of publishing studies as a “myriad of research trajectories without a strong sense of disciplinary cohesion,” and identifies a split between vocational and humanities-oriented research.[14] This empirical study is firmly based in the context of industry-based research and draws on the methodologies of communication, media, and information technology studies.

The conceptual framework for the survey design was informed by the classification of social media tools by Kaplan and Haenlein[15] and the Rogers’ model of innovations diffusion with its five adopter categories: innovator, early adopter, early majority, late majority, and laggard.[16] Their application is supplemented with the examination of other user characteristics such as age, gender, personality, and privacy concerns. The analytical part of this study draws on the technology acceptance model (perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use).[17] In 2010, Cha’s study of social networking use amongst college students, the perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use were related to both frequency and the amount of social networking site use.[18] The present study evaluates whether a similar relation exists in the way editors use social media. This report also analyzes the editors’ motivations following the uses-and-gratifications model, and more specifically the five chief predictors of Internet use identified by Papacharissi and Rubin: interpersonal utility, passing time, information seeking, convenience, and entertainment.[19]

Methodology

To fill a gap in the research on social media use, a survey instrument was employed to elicit responses from publishing professionals carrying out structural editing, copyediting, or proofreading on any type of publication (book, textbook, scholarly journal, government or corporate publication, website, etc.) as a significant part of their everyday work.

A preliminary review of existing literature and the nature of the editing profession have led to the decision to focus on the most popular text-driven social media tools. Hence this research explores three of the six types described by Kaplan and Haenlein (Tab. 1), which are characterized by low to medium degree of social presence and media richness, but can require a high degree of self-presentation and self-disclosure.

| Social presence/media richness | |||

| Low | Medium | ||

| Self-presentation/self-disclosure | High | Blogging, micro-blogging (Twitter) | Social networking sites (Facebook and LinkedIn) |

| Low | Collaborative projects (Wikipedia and social bookmarking) | n/a | |

An online survey was designed using Google Docs to measure the level of adoption of these groups of social media tools and their perceived usefulness in the context of work. The survey was distributed via email to the members of state-based societies of editors in Australia, as well as posted on Twitter and LinkedIn. The first invitation was sent out on July 6, 2011, and several reminders were posted on Twitter in the following three weeks to improve the response rate. Various societies of editors in the United Kingdom, United States, and Canada were also approached via email but did not respond. The survey included five sections: (1) demographics, (2) measure of the degree of familiarity and use of various social media tools, (3) attitudes, (4) work context, and (5) optional contact details for follow-up and dissemination of information. Descriptive quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS and Microsoft Excel.

Results

Between June 6 and 30, 2011, 329 completed surveys were collected (an additional entry was added on July 12). Just over 70 percent of the respondents came from Australia, which was to be expected from the email distribution of the survey. Thirteen percent (44 respondents) came from the U.S., and 7 percent (24) from the UK; another eight replies came from Canada, and two from New Zealand. The remaining 18 respondents are based in other countries including Italy (8), India (2), and single individuals from Ecuador, Germany, Greece, India, Ireland, the Netherlands, Panama, and South Africa.

Of the total sample, 83 percent of respondents were female, which is typical of the editing profession. More than half of the respondents (57 percent) work freelance, while 25 percent are employed in-house, and the remaining 16 percent combine the two modes of employment.

Among the 330 respondents to the survey, 74 percent (245) respondents reported using social media in the context of work. The percentage is slightly different when taking only Australia-based editors into account with 66 percent of social media users, most likely a result of a greater use of email to distribute the survey.[20] These results, however, must be read in light of the limitations discussed later.

User characteristics

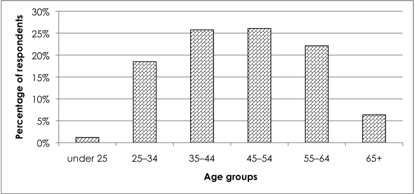

The sample respondents were evenly distributed across the various age groups between 25 and 64 years old, with few aged 65+, and even fewer aged under 25 (fig. 1).

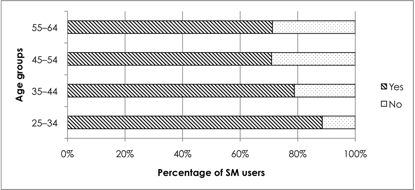

With the exception of those aged 25–34 (and those under 25 and 65+ who are too few to be representative), there seems to be no significant relationship between age and the adoption of social media tools (fig. 2).

This finding is not surprising, as social networking sites such as Facebook and LinkedIn are no longer the exclusive domain of young adults. In fact, the group of mature-aged social networking users appears to have experienced the greatest growth. This is supported by the Pew Research Center report, in the U.S. between April 2009 and May 2010 the use of social networking tools among Internet users aged 50 and older increased from 22 percent to 42 percent, and for those 65+ grew from 13 percent to 26 percent. In comparison, while those aged 18–29 remained the heaviest users of social media, the overall growth for this group was relatively minor—from 76 percent to 86 percent. Nearly half (47 percent) of Internet users aged 50–64 and one in four (26 percent) users aged 65+ used social networking sites.[21]

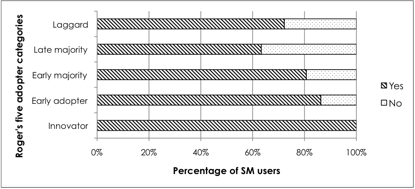

The notion that the so-called digital natives (i.e., those born after 1980) are automatically more technologically adept than the “digital migrants” of previous generations has been found lacking.[22] For example, a study of academics’ use of social media established that age is a “rather poor predictor of social media use in a research context.”[23] Using the Rogers’ model of innovations diffusion and five adopter categories,[24] the researchers found that “innovators” and “early adopters” of technology were 1.26 times more likely to use social media in a work context.[25]

The results of this survey corroborate those findings: the percentage of respondents using social media is higher among editors who described themselves as “innovators” and “early majority” in terms of their attitudes to emerging technologies, in contrast to the more sceptical “late majority” and traditional “laggards” (fig. 3).

The findings of the survey also show no discernible link between age and different stages of innovation adoption in the group aged from 25 to 64, even though “innovators” are typically younger. Once again it shows that the relationship with technology is far from being a straightforward relationship with age, and other variables need to be taken into consideration such as perceived usefulness and ease of use, technology familiarity, self-efficacy, and attitudes toward the Internet.

Apart from association with technology, previous research has established that three personality traits—extraversion, neuroticism, and openness—were positively related to social media use and influenced by age and gender. Neurotic men of any age, and extroverted women and men (particularly among the younger generation) were more likely to be frequent users. In contrast, “being open to new experience emerged as an important personality predictor of social media use for the more mature segment” (i.e., adults aged 30+).[26]

As mentioned earlier, the somewhat higher percentage of women using social media could be related to the results of prior research, which indicate that women are more interpersonally oriented than men and have a stronger motive for interpersonal communication.[27] While both men and women spend a similar amount of time online, it has been reported that women spend more time maintaining relationships and communicating with people.[28] Women tend to focus on “deep” versus “many” connections, which can be detrimental to the development of professional networks.[29] Men are more likely to be early adopters, are more information and task oriented,[30] and tend to gravitate towards transactional sites, providing access to news, sports, and financial information.[31] They are more likely than women to use social media for networking and making new contacts.[32] While both male and female editors use social media, they most likely gravitate towards different tools and use them in different ways. This area requires further investigation into the particulars of how individual editors engage with social media.

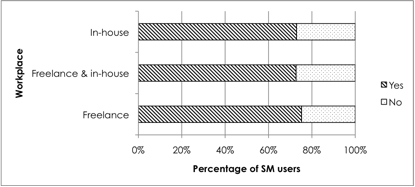

Regardless of whether editors are working freelance or in-house, a similar percentage of respondents reported using social media tools (fig. 4).

Editors and proofreaders that reported doing other work apart from copyediting or proofreading are more likely to use social media (76 percent versus 62 percent), especially those who are professional writers (80 percent). This is most likely related to the opportunities created by social media to promote their writing and connect with readers.

Uses of social media tools

The survey made no distinction between users and “produsers” of social media, however, even if the degree of engagement and participation is unknown, interesting conclusions can be drawn from looking at social media awareness, and the frequency and length of use of various social media tools. The non-users of social media have been excluded from the analysis in this section of the paper (i.e., the results are based on the 245 respondents who reported using social media in the context of work). They are referred to here as SM respondents or SM users for clarity.

The majority of SM respondents who reported using social media know of the different platforms available, with the exception of social bookmarking, with 41 percent of editors being unaware of these tools, which may explain its low adoption rate of only 9 percent (fig. 5). This contrasts with the global trends in social media use, where the social bookmarking site StumbleUpon is the second most commonly used social media site worldwide after Facebook.[33]

In contrast to social bookmarking, all SM respondents are familiar with Facebook and 80 percent of SM users are members of the Facebook community. A similar percentage of SM users are part of LinkedIn (78 percent). Blogging and micro-blogging are slightly less popular; 57 percent of SM respondents reported using a blog, and 23 percent supplied a web address indicating that they maintain or contribute to a blog. Micro-blogging platforms are used by 54 percent of SM respondents (27 percent supplied a Twitter address), and 58 percent of SM users have used a form of wiki in the past.

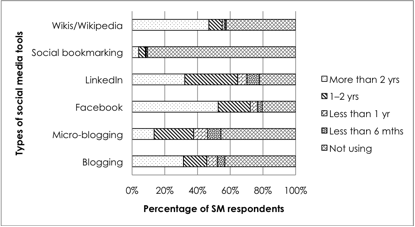

Social media is not a new phenomenon and, accordingly, the majority of SM users have been using the different tools for a while (fig. 6). For example, more than 66 percent of Facebook users have been active for over two years, and 91 percent for more than a year. Other platforms show a similar adoption pattern, with the majority having used a particular platform for over a year (80 percent of blog users, 69 percent of micro-blog users, 83 percent of LinkedIn members, 87 percent of social bookmarking users, and 96 percent of wikis/Wikipedia users).

The survey shows different patterns of engagement with SM tools (fig. 7). Almost 74 percent of Facebook users are active at least once a day. Micro-blogging is also frequently used, with 71 percent of users checking or posting at least once a day. The respondents use LinkedIn less frequently than Facebook, with just over 39 percent of LinkedIn members engaged on a weekly basis, and a further 23 percent on a monthly basis. Wikis/Wikipedia are used at least once a day by 34 percent of users, and on a weekly basis by a further 36 percent. The patterns of blog use require further research to distinguish between reading blogs and contributing content. As mentioned previously, social bookmarking is used by only 22 editors and does not show a distinctive pattern of use.

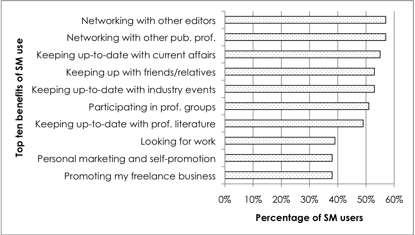

A number of potential uses of social media tools within the context of work, both freelance and in-house, have emerged from this study and warrant further investigation. The top ten most common of uses of social media tools amongst the survey participants are shown in figure 8.[34]

So, how do editors use social media at work? There is no doubt that some social media sites can be useful “tools” in the actual editing process, and not just “weapons of mass distraction” incompatible with the focused attention that editing requires.

Text editing

Several respondents commented on Wikipedia being a good and efficient starting point for preliminary research and fact-checking, leading to more accountable sources. Although its value is still questioned by some editors, research “indicates that Wikipedia is equal to, or even outperforms, comparable conventionally edited encyclopaedias in terms of accuracy.”[35]

Other social media tools can also be helpful with research—posting a quick query on Twitter or LinkedIn enables one to draw on the expertise and knowledge of dozens of editors and proofreaders to “get a consensus opinion.” As one editor wrote, one can “discuss all those niggling questions, like should I hyphenate ‘machine gun wielding fanatic.’” Another commented that social media tools allow to link to a range of “people with in-depth information on whatever one needs.”

Apart from interactive problem-solving and research, social media tools can facilitate collaboration. Wikis offer the ability to collaborate and build communities of practice centred on specific issues. For example, one of the respondents has beta-tested an in-house wiki focused on editorial issues. Unfortunately, it was not implemented but such projects are likely to become more common. Google Docs, another example of social media tools, can be used to share edits and comments, and collaborate with writers when editing. Skype can be used to discuss the editing and publishing processes. With cloud computing becoming more popular, the opportunities to share documents with authors, editors, and publishers, and to communicate and collaborate online will again grow.

Networking

In addition to facilitating collaboration, social media sites, such as LinkedIn, can help people build and maintain a professional network, which many respondents of the survey regard very highly.

The ability to build relationships with other members of the industry is important. In fact, it has been said that, “About 75% of the skills of an editor lie in her relationship with authors and other publishing staff, while the remaining 25% relate to the requirements of editing a text.”[36] While face-to-face interaction is invaluable, it is not always possible, and this is where social media can help. This is not to say that using social media tools can or should replace professional communication via email or phone, especially when working on a manuscript or in any other situation when privacy and confidentiality is required.

Professional development

Typically graduates of editing courses, early-career editors rarely have the benefit of in-house mentoring and gaining experience under supervision. The apprentice-style approach has been largely superseded by increased outsourcing and turnaround in response to economic pressure. In contrast, the experienced editors, who often work freelance, may also need ongoing mentoring, if not in the craft of editing then perhaps in the intricacies of running a business. They may need motivational support and help to stay abreast in the rapidly changing digital climate. Social media can link these two groups together, bringing some of the apprentice-style learning back to share enthusiasm and experience while strengthening the industry in general.

People follow others on social media sites not only for networking and peer support, but also for information.[37] Survey respondents rated highly the ability to stay informed about industry news and upcoming events, and keep up-to-date with professional publications. Micro-blogging can be a great source of quick updates on current news items related to the publishing or editing field, as well as professional events, while social bookmarking tools “allow users to store, tag, organise, share and search for bookmarks (links) to resources online.”[38] Because bookmarks are tagged they can be easily found and quickly retrieved when needed.

The uptake of social media tools by editors’ societies[39] shows how these platforms can be put to administrative uses, such as broadcasting details of new resources, training, seminars, and the latest events. While these have been and remain distributed via email limited to the specific society’s membership, Twitter and Facebook allow editors in other states and countries to learn about these events. It also allows the societies to expand their membership through publicity, earn additional revenue by opening events to non-members thereby improving their ability to increase support, and run more events, etc.

In pre-social media times, becoming aware of an industry event on other side of Australia or the world resulted in no more than that awareness. In contrast, now social media allows for a degree of participation. For example, the use of hashtags on Twitter (e.g., #edconf11) has added an extra dimension to time- and location-sensitive events, such as conferences and public lectures allowing more people to follow the real-time discussions, ask questions, provide feedback, and additional information. Apart from live micro-blogging, it is not unusual for attendees to “Storify”[40] tweets with hashtags, write post-conference blog posts, or for the event organizers to upload video clips on YouTube.

There is no doubt that social media significantly contributes to the information explosion, but at the same time it provides tools to manage information overload. Having a network of colleagues with similar interests on Twitter or other social media platforms helps to filter the information effectively, and aids discovery of useful and interesting resources.[41] These results are different to those acquired using the traditional search technologies (e.g., Google). According to Cann, “‘search’ can provide you with answers only to the questions you ask, whereas social media can also provide you with intelligently filtered information that helps to stimulate new questions, in the same way that a conversation with a colleague might.”[42]

Apart from using social media to find, organize, and share information useful in professional development, improvement of social media skills can be valuable in itself. One of the respondents commented that the use of social media shows willingness to learn and ability to use new technologies for promotional purposes. Apart from making one “appear tech savvy,” social media creates new work opportunities such as assisting authors with social media presence. It can also be used to find work.[43]

Marketing and self-promotion

Social media is changing the way goods and services are marketed, moving away from a traditional one-way communication and paid advertising to interactive and multi-directional communication between brands and consumers.[44] Publishers increasingly often require their authors to engage in the virtual promotion of books and to build a profile using social media tools. While for editors possessing a digital profile is not yet a prerequisite, it can be used for marketing and self-promotion. According to Dorman and colleagues, editors need to be “able to market themselves successfully as the consummate employee or service provider.”[45] It is also increasingly common for contractors to source freelances, and for recruiters and HR managers to look for and investigate potential candidates, on sites such as LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter.[46]

Using social media for marketing is not about making direct sales but more about building a presence, credibility, and reputation that associates editors and proofreaders with their business and the solutions they provide. Not surprisingly, social media, especially Twitter, has been described as a digital “word of mouth.”

With the explosion of web-based publishing and self-publishing, book publishers are no longer the main source of freelance work. In the higher education sector, getting one’s thesis copyedited is almost standard nowadays, with a specific set of rules existing for editors and proofreaders who undertake these. There is a great need, however, to educate customers as to what editors do and why having one’s work edited and proofread is beneficial.[47] Blogs in particular can be used for accessing and dispensing editing-specific information and advice, and promoting the value of editing and proofreading in general.

Drivers and benefits of social media use

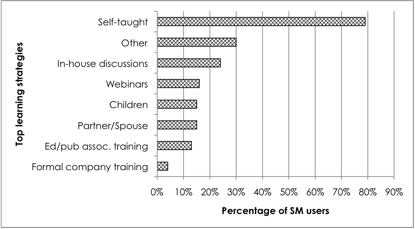

While the survey findings indicate numerous uses of social media tools for work, the majority of editors develop social media knowledge and skills, and stay up-to-date through self-directed and informal learning (fig. 9).

The prevalence of informal and self-directed learning among the sample population shows that personal motivation is an important driver of social media adoption.

The ability of users to easily acquire social media skills—indeed only 16 percent of respondents commented on the lack of skills as a barrier to social media use—is consistent with the technology acceptance models where the perceived ease of use is one of the fundamental determinants in engagement.[49]

In the context of uses-and-gratifications perspective, interpersonal utility and information-seeking appear to be the leading motivators for using social media. Interestingly, the convenience aspect did not rate highly, at least not explicitly. Neither did the other two motives: passing time and entertainment. On the contrary, these features of social media are seen as major drawbacks. Instead, this study identified marketing and self-promotion as important motives for social media use. This is not surprising, considering the study focused on the use of technology-mediated communication in the context of work.

Social media tools are perceived as being “free” to use, easy to learn, flexible, and convenient. The chief benefits identified in the study include the opportunities for broadening the skills of editors and proofreaders, sharing knowledge, developing communities of practice, and improving on some of the negative aspects of the freelance work environment such as isolation or lack of peer support.

The ability to communicate and stay virtually “connected” is valuable, as editing can be a very solitary occupation, especially for those working freelance. A few of the respondents commented on the high percentage of introverts that the editing profession seems to attract. While introverted personalities may struggle with the extent of self-disclosure required, they can participate in social media to a degree of interaction and exposure that feels comfortable. They can start their social media career as “lurkers” or “casuals,” “users” rather than “produsers,” and select the media that is low on self-presentation and self-disclosure.

Although social media tools may appear less useful for those well established and active in editors’ societies and other networks within the industry, even well-connected editors can benefit from the serendipitous nature of social media. The informal conversations happening on social networks have been compared with the “water cooler moments” at work, which are said to play “an important role for collaborative work, peer support and organizational innovation.” The research shows that “a greater proportion of novel information flows to individuals through weak [rather] than through strong ties,” and weak ties are typical of online social networks.[50]

Social media tools also provide a low-cost and easy way to market and promote editing services, and can help individuals in finding new work. Moreover, social media has the potential to influence the way the profession is perceived within and outside of the publishing industry, providing an opportunity to foster greater understanding and recognition of editors’ and proofreaders’ roles in the publishing process.

One of the respondents commented: “Social media has revolutionized the way I work. I don’t know how I’d cope without it.” Such sentiments, however, are not uniform and despite the great potential represented by social media, the perception of individual tools vary.

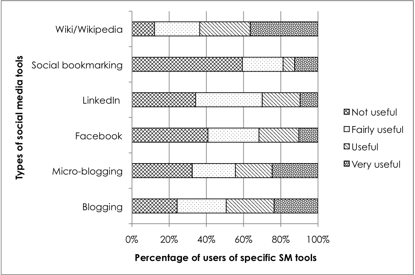

Not surpisingly, in view of its low awareness, only four respondents reported to have found social bookmarking very useful (fig. 10).[51] Despite the high frequency and length of use of Facebook, 41 percent of Facebook users do not consider it to be valuable in the context of work. While LinkedIn is seen as somewhat more useful than Facebook in the work context, only 36 percent of its users considers the network to be fairly useful and almost 34 percent of users do not see its value. Over three-quarters (76 percent) of blog users considers the medium useful in the context of work to a varying degree. Similarly to the perceptions of blogs, 68 percent of micro-blog users perceive the medium as useful in the context of work. Wikis/Wikipedia is the most highly regarded platform, with 88 percent of the users considering the platform to be practical to a varying degree—from fairly to very.

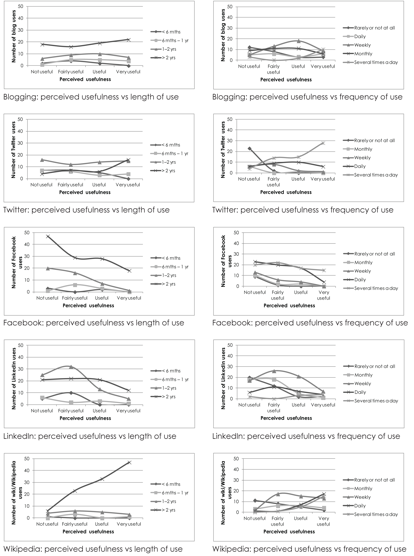

The preliminary analysis (fig. 11) has shown that the length and frequency of use are positively related to the perceived usefulness in the case of Twitter and Wikipedia, but not other social media tools. Further research is needed to explore the differences in the activities performed using various social tools.

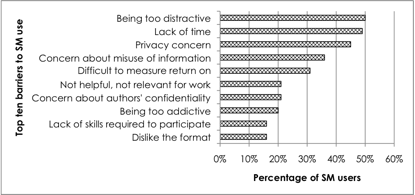

Chief barriers and concerns associated with social media use

Despite the relative advantages of social media tools and their compatibility with many aspects of the editing profession, they are perceived as being time consuming, distractive, and inappropriate for work, and these costs can outweigh the benefits of their use (fig. 12).

Time

Survey respondents repeatedly indicated the issue of workload and the lack of time as two huge factors affecting the adoption of social media tools. Several editors commented that they had no time to explore or be active on social media sites as can be seen in the following examples: “TIME needed to set these things up and monitor them, is by far the biggest barrier”; “to do it well is quite time-consuming”; it “takes a lot of time to ensure that posts are appropriate/accurate (no typos etc.).” Others were concerned about the uncertain return on investment of time and the distractive nature of social media sites—seen as detrimental to the sustained concentration required to edit, and as a potential for wasting time away from actual editing.

There is no doubt that the process of building and curating an effective network takes time. But as Cann pointed out, most platforms offer ways and strategies to find people with similar interests and “once you have started building a network it becomes useful very quickly.”[53] And those networks do not have to be large to be effective. In fact, “There are benefits in having large and diverse networks, but over-complexity is the enemy of efficient communication, leading to noise rather than information.”[54] According to the anthropologist Robin Dunbar, an average person can successfully maintain around 150 genuine social relationships for a number of evolutionary and sociological reasons,[55] which may explain why some people feel overwhelmed and distracted by social media.

Once social networks are in place, they require a commitment of time and constant, but not incessant, attention with different expectations of what it means to have an active presence on specific platforms: from at least daily tweets on Twitter to less frequent—once a week or once a month—but regular blog posts. Consistency is the key. As Evans commented, “On the Social Web, if your profile isn’t up-to-date, if you’re not commenting, if you’re not making connections, you don’t exist . . . make sure you can commit to keeping it alive.”[56]

Perception of social media

Apart from time concerns, Twitter and Facebook in particular can be perceived as “a social/young person’s tool,” irrelevant and unprofessional rather than beneficial. In fact, Twitter was described by one of the respondents as “the biggest waste of time and brain space of all time.” The short form of Facebook status updates and Twitter posts has led many to believe that social media are banal, “trivial in nature and suitable only for entertainment,”[57] rather than useful in a professional context.

Undoubtedly, there is a lot of “daily chatter” or “pointless babble” happening on social media sites, but users have an option to “unfollow” the producers of uninteresting or useless content. Instead, they should look for authors of posts that provide information or links to interesting URLs, and facilitate useful conversation, even if it is informal and discursive. Others see the use of social media as narcissistic and linked with the desire for fame and celebrity status. Celebrity editors, however, have been around for over a century and a few self-promotional tweets are not going to turn an editor into a star.

Some editors expressed concern that being involved with social media tools—perhaps with the exception of LinkedIn—would detract from their reputation as a “serious” professional editor. Moreover, some respondents (and their employers) were concerned that spending time on social media sites instead of editing, would demonstrate that they are somehow less serious about and less committed to their jobs.

Work and life balance

As one of the respondents commented, social media “blurs the boundaries between work and non-work too much, so that you can never entirely leave your work at any point in the day.” The blurring of boundaries between work and leisure time is not a new problem, especially for the editors working at a home office. Undoubtedly, social media has the potential to extend the working day and time spent in front of a screen even further, especially when mobile devices are used for access.

Privacy and confidentiality issues

Respondents were also concerned about the overlap between professional and personal contacts, and the ability to maintain a professional stance. As social media complicates the traditional dichotomies between “public” and “private,” a level of blending between the personal and professional life is inevitable and editors need to assess how comfortable they are with the disclosure of some personal information. A certain degree of disclosure is unavoidable, as “revealing personal information is seen as a marker of authenticity, [though] strategically managed and limited,”[58] and a means to establish trust.[59]

In the case of social networking sites such as Facebook or LinkedIn, it is important to know the privacy policies and understand how the privacy settings operate, keeping in mind that these change often. Being cautious and judicious in what information is revealed remains the safest approach.

The best strategy to deal with issues of privacy and authors’ confidentiality is to assume that everything one writes online can become public. When confidentiality is required it is best to communicate directly by email or phone.

Social media policies

While this is not an issue for freelancers, some companies “forbid or limit access” to social media tools, which affects those working in-house. If not blocked, social media can be seen as “time-wasting rather than beneficial for the employer,” as reported by another respondent.

Other organisations allow or even encourage access, provided employees follow social media policies, which typically prohibit revealing confidential and commercial information, trade secrets, and other corporate information that could be potentially damaging to the business or its reputation.

“Don’t be stupid” seems to be the most common and succinct social media policy, which is well worth heeding, and perhaps in the case of editors it should accompanied by “check for typos before you post.”

Conclusions

So, are social media technologies new editing tools or weapons of mass distraction?

It is clear from the survey results that many editors and proofreaders, working freelance and in-house, are actively and purposefully using social media to support their professional activities.

The survey showed no apparent link between age and the adoption of social media tools between the ages of 25 and 64. A slightly higher percentage of female than male editors use social media. Future research on the population of editors and proofreaders could explore whether this is unique to this sample, or whether in fact more females than males use social media and whether the “nature” of their uses differ.

Overall, the survey results showed that editors and proofreaders in the sample population are well-informed, self-taught, and sophisticated users of social media and consider wikis, blogs, and micro-blogs to be valuable tools in their work context. In contrast, although commonly used, Facebook and LinkedIn are not perceived as useful. In the case of LinkedIn, marketed as a tool for professional networking, this is a somewhat surprising result, though consistent with the model of perceived usefulness and frequency of use: LinkedIn is not used as frequently as micro-blogging, for example.

It is interesting that despite the high adoption of social media tools in the publishing industry, little formal training and encouragement is provided for staff not directly involved in marketing and public relations.

The study identified interpersonal utility, information seeking, marketing, and self-promotion as the leading motivators for using social media. Analysis of the survey results suggests that when judiciously used, social media can be valuable tools for editors and proofreaders, especially those at the beginning of their careers (regardless of age). While many of the respondents commented on the time consuming and disruptive nature of social media, they overlooked the convenience value and time savings resulting from the ability to do preliminary research, stay abreast with industry news and job opportunities, and to network with colleagues without the need to leave one’s desk.

While social media are seen as a distraction from the concentrated attention needed to edit, it is interesting to consider whether taking time out from editing work to catch up with personal Facebook, etc., may actually be refreshing and help people stay motivated at work in an isolated environment.

Much has been written about the invisibility of editing professionals and the need to change this in order to raise their profile, recognize their contribution, and foster a greater understanding of the editor’s role in the publishing industry.[60] While the establishment of the Institute of Professional Editors (IPed) and the introduction of a formal accreditation system are important steps towards increased professionalization and wider recognition of editors and proofreaders within the Australian publishing industry, social media has the potential to promote the value of editing and increase editors’ profile on an even wider scale. As Deanna Zandt wrote, “without visibility, we are not valued. If we are not heard, we can’t make a difference.”[61]

Social media is blending the boundaries between the public and private life, work and leisure time, but the degree of fusion remains in the hands of the social media user. Theoretically, it is up to the individual how much disclosure happens online, what platforms are used, what privacy settings are chosen, who is followed and befriended, what types of posts are sent, what can be automated, and how much time is spent on these activities. Social media tools are flexible and able to cater for any personality, provided one is open enough to give them a try. It is important to keep in mind that the definition of a “friend” is much wider in this sphere than in reality, and also that anything posted online is permanent and can become public through cross-posting and because social media sites often change their privacy policies. Moreover, users have little control over what other users can do with the information provided.

Editors and proofreaders need to establish clear objectives in order to use social media effectively in the work context and allocate the time and attention effectively. They will be in a better position to decide on the most suitable strategies including the size of networks, the type and frequency of posts, and the degree of personal disclosure. It is worth remembering that social media tools operate on the basis of gift economy—the more time and effort is invested, the higher the rewards, whether in the size of one’s network, one’s reputation, or ranking.

Finally, editors and proofreaders also need to develop performance indicators and monitor whether they are achieving their objectives and priorities. Social media is merely a tool, and it is only as effective as the person using it.

Limitations and future research

Designed as an exploratory study, the results of the survey have limited generalizability due to the inherent bias introduced by sampling and distribution. Without knowledge of the overall size of the population of editors and proofreaders worldwide, assessing the overall response rate is not feasible. In the case of Australia-based editors, the response rate was just over 14 percent of the total membership of the editors’ state societies. This percentage, however, cannot be taken as representative as some of the editors that responded to the survey were not society members. Also, it is unknown what percentage of editing professionals are members of the state societies in Australia. A different sampling procedure may address some of these problems in future studies.

The survey relied on respondents self-reporting and future research should focus on content analysis to eliminate the bias and validity problem, and explore the actual use of various social media tools. This should take into consideration the distinction between “users” and “produsers” of social media and allow for in-depth analysis of social media engagement.

Agata Mrva-Montoya has worked at Sydney University Press since 2008, in a role combining editing, project management and social media. She is interested in the impact of new technologies on scholarly publishing, editing and books in general. In pre-publishing life, she completed a PhD in archaeology. She is also a member of Human Animal Research Network at the University of Sydney and can be found on twitter as @agatamontoya.

Acknowledgements

The survey results were first presented at the 5th National Editors’ Conference in Sydney, Australia, (September 8–9, 2011). I am grateful to Rosina Mladenovic, Susan Murray-Smith, and Debbie Perik for their help with survey design and comments on the paper. I would also like to thank Paul Scifleet for reviewing the paper and his constructive feedback.

Notes

J. Bullas, “5 ways to integrate social media into your company’s DNA,” 2010, http://www.jeffbullas.com/2010/12/23/5-ways-to-integrate-social-media-into-your-companys-dna/.

December 2011, http://newsroom.fb.com/content/default.aspx?NewsAreaId=22.

See for example L. Cerand, “Social media for authors: forever in search of buzz,” Poets & Writers Magazine 39, no. 3 (2011): 71–75; Nina Hendy, “Social media the new key tool in selling books,” Sydney Morning Herald, July 15, 2011; and Sara Sheridan, “Why writers must embrace social media, no matter the genre,” Literary Edinburgh, The Guardian, April 14, 2011.

Meredith Nelson, “The blog phenomenon and the book publishing industry,” Publishing Research Quarterly 22, no. 2 (2006): 3–26; P. Clifton. “Teach them to fish: empowering authors to market themselves online,” Publishing Research Quarterly 26 (2010): 106–9; Anne Thoring, “Corporate tweeting: analysing the use of Twitter as a marketing tool by UK trade publishers,” Publishing Research Quarterly 27, no. 2 (2011): 141–58, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12109-011-9214-7; Xuemei Tian and Bill Martin, “Digital technologies for book publishing,” Publishing Research Quarterly 26, no. 3 (2010): 151–67.

Louise Poland, “The businees, craft and profession of the book editor,” in Making books: contemporary Australian publishing, ed. David Carter and Anne Galligan (St Lucia, Qld.: University of Queensland Press, 2007), 114.

M. Dorman, S. Nevile, J. Wright, and R. Dearden. “Editors map their past to inform their future: how well are they reading the signs?” National Editors Conference, Tasmania, 2008, http://www.tas-editors.org.au/conference/dorman.html.

“The complete guide to social-media marketing and business paper,” CIO White Paper, 2010, [formerly http://a.ciowhitepapers.com/wstatic2/FinalVersion2011.pdf].

David Meerman Scott, “Social media debate,” EContent 30, no. 10 (2007): 64, http://www.econtentmag.com/Articles/Column/After-Thought/Social-Media-Debate-40186.htm.

Andreas M. Kaplan and Michael Haenlein, “Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media,” Business Horizons 53, no. 1 (2010): 60–61, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003.

SAS, “Social media metrics: listening, understanding and predicting the impacts of social media on your business,” in eMetrics (San Jose, CA: SAS Social Media Analytics, 2010).

A. Bruns, “Some exploratory notes on produsers and produsage,” ID Currents, Institute for Distributed Creativity, 2005, http://distributedcreativity.typepad.com/idc_texts/2005/11/some_explorator.html.

B. Elowitz, “The web is shrinking. Now what?” Digital Network: All Things D, Wall Street Journal, 2011, http://allthingsd.com/20110623/the-web-is-shrinking-now-what/.

Simone Murray, “Publishing studies: critically mapping research in search of a discipline,” Publishing Research Quarterly 22, no. 4 (2007): 1.

Kaplan and Haenlein, “Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media,” 60–61.

Everett M. Rogers, Diffusion of innovations, 4th ed. (New York: Free Press, 1995), 262–66.

Jiyoung Cha, “Factors affecting the frequency and amount of social networking site use: motivations, perceptions, and privacy concerns,” First Monday 15, no. 12 (2010).

Cha, “Factors affecting the frequency and amount of social networking site use: motivations, perceptions, and privacy concerns.”

Zizi Papacharissi and Alan M Rubin, “Predictors of internet use,” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 44, no. 2 (2000): 175–96.

These results are comparable with the findings of RightNow Research released on July 27, 2011, showing that the number of Australians actively using social media has jumped from 53 percent to 69 of the total population in the last 12 months. http://www.prwire.com.au/pr/24118/new-rightnow-research-signals-growing-influence-of-social-media-on-consumer-purchasing-decisions.

Mary Madden, “Older adults and social media: social networking use among those ages 50 and older nearly doubled over the past year,” (Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center 2010), 2, http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Older-Adults-and-Social-Media.aspx.

Siva Vaidhyanathan, “Generational myth: not all young people are tech-savvy,” Chronicle of Higher Education 55, no. 4 (2008), http://chronicle.com/free/v55/i04/04b00701.htm.

University College London CIBER, Emerald Group Publishing Ltd, “Social media and research workflow,” in University College London (2010), 2; Rowlands et al., “Social media use in the research workflow,” Learned Publishing 24, no. 3 (2011): 187–88, http://dx.doi.org/10.1087/20110306.

E. M. Rogers, Diffusion of innovations (New York: Free Press, 1995), 262–66.

T. Correa, A.W. Hinsley, and H. Gil de Z˙Òiga 2010. “Who interacts on the web? The intersection of users’ personality and social media use,” Computers in Human Behavior 26 (2): 247–53, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563209001472.

Linda A. Jackson, et al., “Gender and the internet: women communicating and men searching,” Sex Roles 44, no. 5 (2001): 368, http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/a:1010937901821.

Nicole L. Muscanell and Rosanna E. Guadagno, “Make new friends or keep the old: gender and personality differences in social networking use,” Computers in Human Behavior 28, no. 1 (2012): 110; “The complete guide to social-media marketing and business paper,” CIO White Paper (2010), http://a.ciowhitepapers.com/wstatic2/FinalVersion2011.pdf.

Deanna Zandt, Share this! How you will change the world with social networking (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2010), 26.

Jackson et al., “Gender and the internet: women communicating and men searching,” 368.

“Men are early adopters of technology, but women dominate social media,” Media Report to Women 36, no. 4 (2008).

Muscanell and Guadagno, “Make new friends or keep the old: gender and personality differences in social networking use,” 110–11.

http://gs.statcounter.com/?PHPSESSID=uf6ve5pll9an2nbfb0t6j8gj20#social_media-ww-monthly-201102-201202. Low use of bookmarking was also noted amongst researchers in the 2010 CIBER research project; see Rowlands et al., “Social media use in the research workflow,” 185.

The survey did not explore how the editors use different platforms specifically as there is a high degree of overlap between them. Respondents could select more than one answer so percentages add up to more than 100 percent.

Alan Cann, Konstantia Dimitriou, and Tristram Hooley, “Social media: a guide for researchers.” (Leicester: Research Information Network, 2011), http://www.rin.ac.uk/our-work/communicating-and-disseminating-research/social-media-guide-researchers., See “Reliability of Wikipedia” for a list of scholarly studies on accuracy and reliability of Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reliability_of_Wikipedia#Comparative_studies.

V. Field after Katya Johanson, “Dead, done for and dangerous: teaching editing students what not to do,” New Writing 3, no. 1 (2006): 50.

Haewoon Kwak et al., “What is Twitter, a social network or a news media?” WWW 2010, April 26–30, 2010 (Raleigh, NC, 2010), http://an.kaist.ac.kr/~haewoon/papers/2010-www-twitter.pdf.

Cann, Dimitriou, and Hooley, “Social media: a guide for researchers,” 25.

For example, on Twitter: @SocEdNSW, @SocEdVic, @EditorsWA, @EFAFreelancers, @TheSfEP, @EditorsBC and @EAC/ACR.

Storify is an application that allows users to collect and arrange media from different streams across the web, in order to tell a coherent, unified story, usually about a specific event or moment.

Cann, Dimitriou, and Hooley, “Social media: a guide for researchers,” 11.

Suzanne Collier, “How to use Twitter to find a publishing job,” in Publishing Talk (2011).

T. L. Tuten, “Advertising 2.0: social media marketing in a Web 2.0 world,” Westport, CT., Praeger, 2008, http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0815/2008016491.html.

Marilyn Dorman et al., “Editors map their past to inform their future: how well are they reading the signs?,” in National Editors Conference, National Editors Conference, Tasmania, 2008, http://www.tas-editors.org.au/conference/dorman.html.

W. Immen, “Setting the stage for career action,” Globe and Mail, December 24, 2010, http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/managing/on-the-job/setting-the-stage-for-career-action/article1849263/.

See for example the recent report on the cost of misspellings to businesses by Sean Coughlan, “Spelling mistakes ‘cost millions’ in lost online sales,” BBC News, July 14, 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-14130854. See also www.kateproof.co.uk.

Respondents could select more than a single answer so the percentage added up to more than 100 percent.

Cha, “Factors affecting the frequency and amount of social networking site use: motivations, perceptions, and privacy concerns.”

J. Joanne Badge et al., “Observing emerging student networks on a microblogging service,” MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching 7, no. 1 (2011): 96.

The question of perceived usefulness of SM tools was analyzed looking at the responses of the users of specic tools by excluding missing data and the “haven’t used” responses.

Respondents could select more than one answer so percentages add up to more than 100 percent.

Cann, Dimitriou, and Hooley, “Social media: a guide for researchers,” 9.

R.I.M. Dunbar, Grooming, gossip and the evolution of language (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1998), 7.

Dave Evans, Social media marketing: an hour a day (Indianapolis, IN: Wiley Publishing, Inc., 2008), 190.

Cann, Dimitriou, and Hooley, “Social media: a guide for researchers,” 11.

Alice E. Marwick and danah boyd, “I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience,” New Media Society 13, no. 1 (2010): 125, http://nms.sagepub.com/content/13/1/114.

Mandy Brett, “Stet by me: thoughts on editing fiction,” Meanjin 70, no. 1 (2011).

Zandt, Share this! How you will change the world with social networking, 100.