The Value of Standards in Electronic Content Distribution: Reflections on the Adoption of NISO Standards

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

The process of managing electronic content is increasingly complex, significantly more so than traditional print distribution. Over the past decade, there have been significant investments in the standardization of various parts of the supply chain of published information. Some of these standards have been successful, some less so. This article describes some NISO standards that impact electronic resource management and reasons why some have been successful and why others have faced challenges in adoption. Since there are limited resources available to standards development, questioning what makes a project successful or not, will help to improve our project selection moving forward.

The distribution of electronic information is significantly more complex than that of the print world, for the distributors of content, the intermediaries that facilitate that information flow, and the libraries who provide it to patrons. Much has been written on the problems of licensing digital content[1], the systems integration issues[2], and the preservation problems[3] related to electronic publication. These are only a few of the many complex challenges of digital information distribution. As with many processes that take place at scale, the benefits of standardization can be tremendous. Over the past two decades, a considerable amount of work has been undertaken to rationalize, formalize, consolidate, and simplify the information distribution landscape. Some of these efforts have been successful, some less so. This article will discuss some of the standards development that has taken place related to the management of electronic resources. It will also highlight the rationale for some of the successes and failures of those efforts in hopes of clarifying what might work better in the future.

Standards for the distribution of content are nothing new and we are extremely familiar with them, even though we don’t always think of them as standards. As publishing first developed, things we now take for granted were usually driven by technological advances in the publication process. Usually they developed as a result of production inefficiencies that needed to be overcome. Page numbers, for example, were developed in the fifteenth century as a way to organize content that was produced out of order, so that they could be bound. Similarly, table of contents, indices, cataloging information, title pages, organization structures, paper acidity levels, binding, paper sizes, ink, and colors are all best practices in the publishing world that became “standardized” over time and have been adapted to provide more efficient discovery and delivery of content. While some of these practices don’t have “official” designation by ANSI, NISO, ISO, or another standards body, they most certainly are de facto standards in the industry that are enforced primarily through production processes or community pressure.

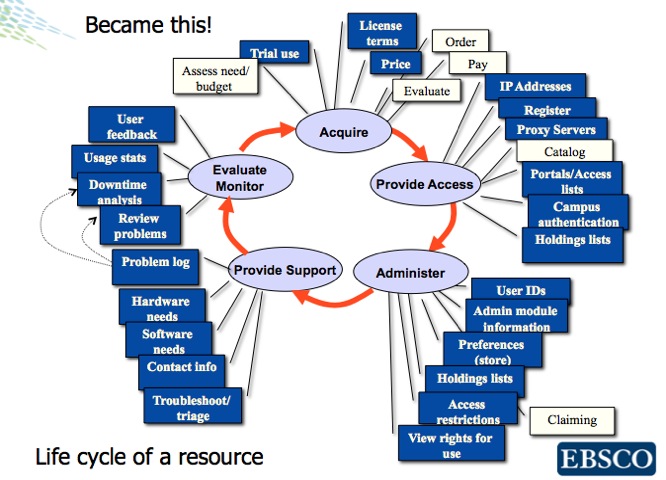

While print distribution to libraries has developed slowly over centuries, the history of the electronic distribution of content is still counted in decades at most and is thus very much in its infancy. Some key differences between the print distribution model in libraries and the process of handling electronic content were described in the Digital Library Federation’s Electronic Resource Management Initiative (ERMI) report[4] published in 2004. As the community has gained more experience with digital distribution, the distribution model described in the ERMI report has continued to be tweaked and expanded. Oliver Pesch, Chief Strategist, E-Resources at EBSCO Information Services, described this circular nature of this process in his presentation at the NISO Electronic Resources Forum in 2006 using the formulation shown in Figure 1.[5] This is contrasted with a process for acquiring, processing, and storing print items that was both more simple and linear, with distinct beginning and end points.

This process is managed easily enough when a library receives content from just a few providers. However, as content sources become more ubiquitous, the challenges increase markedly. As with many things, the “80-20 rule” applies in this case in spades; the 20 percent of content from smaller providers often causes the majority of difficulty. While most larger organizations that provide content electronically are well positioned to provide content with most of the commonly associated services, such as COUNTER[7] reports, preservation through services like Portico[8] or LOCKSS[9], single-sign-on (SSO) systems, OpenURL and linking data, and others, the “long tail” of publishers providing content to libraries in digital form are simply not prepared to provide content with these services. This negatively impacts the discoverability and availability of content for patrons, as well as its usefulness—now and in the future.

This is where standardization has become crucial to address the distribution challenges in our environment. To the extent that an institution receives content from a single source, which is then fed into a single integrated management solution, these issues are less apparent and critical. However, as the sources of electronic content continually increase, the form and scope of that content grows, and the number of systems required for managing it increases, the need for standards increases exponentially.

This has been the case with the flow of information in the subscription process. Pesch’s process for the acquisition of electronic resources, shown in Figure 1, describes the ordering process from content selection through purchasing, to ingest into a management system, through to evaluation and re-purchase. The complexity of this workflow is shown by the information needed in an electronic transaction (formatted in blue) compared with those processes required in traditional print-resource management (formatted in white).

In many phases of this workflow, there is an exchange of information from one system or entity to another. To facilitate these interchanges, standards have been or need to be developed to ease the transaction process. In some cases, the standards are still being identified and developed; in others, the standard has been developed and is awaiting broad adoption and use. Some examples of NISO standards and best practices that affect different stages in the workflow include:

- Shared Electronic Resource Understanding (SERU)[10], a recommended practice that provides an alternative to a formal license in the Acquire stage

- The OpenURL Framework for Context-Sensitive Services[11], a standard that defines an architecture in which a package with a description of a referenced resource is transported with the intent of obtaining context-sensitive services that pertain to the referenced resource (known as an OpenURL), a heavily used protocol in the Provide Access stage

- The Standardized Usage Statistics Harvesting Initiative (SUSHI) Protocol[12], a standard that simplifies the transfer of usage statistics in the Evaluate/Monitor stage

- Knowledge Bases and Related Tools (KBART)[13], a recommended practice for improving the quality of the knowledge bases used with OpenURL as part of the Provide Access stage

A number of additional projects are in the development pipeline, including:

- The Establishing Suggested Practices Regarding Single Sign-On (ESPReSSO)[14] initiative to develop best practices for simplifying a user’s ability to seamlessly access licensed or otherwise protected content in a networked environment using SSO authentication, part of the Provide Access stage

- The Institutional Identifiers (I2)[15] initiative to develop a standard for an institutional identifier that can be implemented in all library and publishing environments, something that would cross over all stages in the lifecycle

Other organizations are working on related elements of this process, including OCLC, EDItEUR[16] and UKSG[17] in the U.K., and the Book Industry Study Group[18] in the U.S. Some of the projects that these organizations have include various transformations and exchanges of metadata, including the ONIX messaging system, the maintenance of rights information, various assessment metrics projects, and various electronic data interchange (EDI) messaging protocols.

Building on ERMI, there have been a number of directly related developments in standards and systems over the intervening years. The ERMI project described the specialized management systems, which have developed over the past decade into robust software service offerings provided by many vendors. These Electronic Resource Management Systems (ERMS) now use standards as the basis for much of their functionality, for example, through a SUSHI client. While some work has been conducted on license expression and significant training has been provided to the community on how one might encode a license electronically, adoption of the ONIX for Publications License (ONIX-PL)[19] structure has been slow to take root. Similarly, the Cost of Resource Exchange (CORE)[20] protocol has not yet been deployed. Other ERM-related initiatives such as SERU and KBART have received significant support and community uptake.

As a community, we should consider why some of these standards have been adopted while others languish. Unfortunately, there are limited community resources that can be directed to standards development and we need to ensure that these resources are expended where the likelihood of successful adoption is the greatest. NISO has built into our procedures a variety of review and consideration opportunities, but these need diligent engagement to ensure the projects undertaken will provide the greatest value and impact for the community.

One of the more successful NISO initiatives over the past five years has been the SUSHI protocol. Measuring and monitoring the use and value of electronic resources is a critical element in the evaluation process for whether to re-subscribe to an e-resource. However, as the number of subscribed resources and the various aggregators supplying them has expanded, the process of gathering usage statistics from content providers quickly grew unwieldy. A variety of anecdotal reports indicated that librarians were spending more time gathering and organizing usage data than analyzing it. The community needed a system to automate and simplify the gathering of usage data for librarians. The SUSHI Protocol has been successful for four key reasons: the pervasiveness of the problem that it addresses, tying compliance to existing end-user expectations, the relative simplicity of its implementation, and the ongoing support and education that is provided surrounding the standard.

In 2007, NISO published the SUSHI protocol (ANSI/NISO Z39.93), which described a server/client system to exchange COUNTER reports using lightweight web-transfer protocols. The system is incorporated into usage systems on the provider (server) side or into an ERMS (client) on the library side. The standard provides for simpler data exchange with much less human interaction. In the fall of 2009, the SUSHI standard was incorporated into Release 3 of the COUNTER Code of Practice for Journals and Databases[21]. In order for publishers to be certified as COUNTER-compliant, they must also be compliant with the SUSHI standard. There are currently more than 132 publishers that are providing at least one COUNTER 3-compliant usage report, which implies a working SUSHI implementation.

There are a variety of factors that have driven the adoption of the SUSHI standard since its release. The first critical element of the standard’s success was the broad-based need for a solution to the problem. Almost every library that subscribes to electronic publications needs to collect and review its usage data. As the majority of libraries are subscribing to an increasing number of resources, the pain of dealing with this process impacts almost every institution—and the publishers or aggregators that supply the data to the libraries.

Tying the new SUSHI standard to compliance with the COUNTER Code of Practice was a significant driver for SUSHI adoption. COUNTER had established market credibility for its leadership role in the space of usage data and demand for data following the COUNTER principles, so much so that many institutions reference COUNTER compliance in their contracts for e-resources. When COUNTER added SUSHI compliance to its Code of Practice, it immediately drove all the existing COUNTER report providers to implement SUSHI.

Part of the success of SUSHI can be attributed to the fact that it is a relatively easy protocol to implement. Designed from the outset to be based on existing protocols for web services, SUSHI implementers were able to utilize many of the existing tools to simplify web service development. This further reduced the barriers to adoption.

Finally, a support mechanism for developers was established when the standard was in its trial stage and implementers have generously shared their knowledge and assistance to new developers. At the time the standard was published, NISO also established a SUSHI Standing Committee that continues to provide ongoing support maintenance of the XML schemas, and supporting documentation, which further helped adopters. There have also been a number of educational events, presentations at conferences, and open-source toolkit contributions to the community, which contributed to awareness and understanding of the new protocol.

Another initiative that has seen significant adoption is SERU. Licensing of electronic resources is often a challenging, time-consuming, and intellectually taxing process. It adds significantly to the costs of subscribing to content and slows the process of acquisition. In the cases where the risks are perceived to be low, it often doesn’t make sense to engage in a lengthy or costly license negotiation. The goal of SERU is to reduce the transaction costs of negotiating licenses by using a framework for community-held best practices regarding delivery and management of electronic content. This framework is possible based on a decade of growing mutual trust and experience with digital information where a broad consensus has developed on issues such as authorized users, third-party archiving, improper use, and systematic downloading. Agreement to use these common principles is then referenced in the terms of sale document, such as an invoice.

SERU has also seen significant success in adoption since it was released in 2008 as a Recommended Practice (NISO RP-7-2008). Presently, 153 libraries, 8 consortia, and 58 publishers and content providers have registered[22] their willingness to use SERU in lieu of a license.

Like SUSHI, the main drivers that have propelled SERU’s adoption relate to its simplicity and the ubiquity of the problem. The SERU document was drafted in easy to understand language and was developed with a narrow scope in mind. The recommended practice also provides an elegant remedy to remove the real transactional barriers experienced by both publishers and libraries negotiating licenses. The team behind SERU has been clear from the outset that they were not trying to replace all licensing, only in those cases where the perceived risks were low enough (as determined by the parties to the sale), that a license wasn’t required. At its heart, SERU provides significant cost savings and facilitates sales on both sides of the transaction. Also like SUSHI, there has been significant education and promotion of the value provided by the Understanding.

While there are other successes, there are also projects that have yet to see the broad adoption of projects like SUSHI, SERU, or KBART. Reviewing why these initiatives have had limited adoption is valuable to considering whether other similar projects will be successful in the future. For example, the challenges surrounding license expression has limited the wide adoption of the ONIX-PL messaging system. Similarly, the CORE messaging protocol for communicating price and use information between library systems has been slow to be adopted, but for other reasons.

The ONIX for Publications Licenses is a structure for making the content of a license machine-readable through the use of an extensible XML structure. Designed as a tool to make license terms and conditions more accessible, ONIX-PL is extensible so additional terms can be added to dictionary in the future. Another core element of the messaging system is that the message is neither actionable (i.e., they don’t control access to content), nor is it a replacement of the legal language in a license. ONIX-PL encodings are open to interpretation by the parties using the messages.

There are a variety of challenges facing the adoption of license expression structures. Clearly, communicating license permissions and prohibitions to staff and users is difficult and understanding the exact meaning of contract language is challenging even for people well versed in their use. Simplifying and codifying license language is also not a simple process. In addition, there exists a question of the inherent value proposition of having licenses encoded in a system. Because of the time and energy required to encode a license, is the encoding process worth more than the costs involved? Not every organization will need the level of detail that an ONIX-PL encoding could provide and there are few guidelines about how much or little encoding needs to be done.

While there may be value to having licenses encoded, few organizations see the sufficient value to their own institution to undertake the encoding work. There could be efficiencies of scales and some organizations have expressed interest in providing this service to the community; however, there is potentially some legal risk to encoding a license that is not directly one’s own. While some organizations like the JISC in the U.K. are undertaking this work, the lack of a self-motivated community willing to invest in encodings that everyone else could use, has also inhibited adoption. In the end, the real question will come down to whether the cost threshold of managing licenses badly is less than the costs to implement a better solution.

There is also a chicken and egg problem with the development of communication structures such as ONIX. A communication structure isn’t really useful until there is at least a critical mass using it; otherwise, there is no one to communicate with. This problem applies equally to both the CORE & ONIX-PL standards. There is little benefit to the provider to create something before the customer is ready to use it, especially when there is significant programming investment. A partnership is required between at least two systems providers to make these communication structures function and these system providers may not have the same goals or priorities. Implementation could get delayed unless both vendors are willing to work together to launch the service. Both system providers will also be looking to their customers to drive their priorities and these customers may also differ (e.g., the publishing community and the library community may not place ONIX-PL implementation at the same priority level). Even within a community, there could be priority issues; adding CORE functionality to an ILS could have different importance than adding it to an ERM system, yet both are needed before a CORE protocol transfer can occur. All of these things can delay or even derail the adoption of a standard.

Electronic Resource Management (ERM) is, generally, a complicated process, considerably more complicated than the previous print environment. This compounds the challenges surrounding the creation and adoption of ERM systems and related standards in institutions. For many reasons, the management of e-resources didn’t fit well within existing ILS systems and the creation of a new breed of systems and procedures was required. These systems and the needed functionality are still evolving, at times in fits and starts, along with the evolution of electronic resource distribution and access. However, just like the print world, the investment in standards and best practices regarding management of digital resources will pay significant benefits moving forward. This is especially true in an environment where e-content management staff levels are comparatively low compared to the staffing level of managing print content. With ongoing economic limitations on adding staff and even reductions in staffing levels, focusing on ways to reduce the order processing and management issues is the best way to expand the provision of e-resource to patrons.

As a community, we need to be diligent in looking for ways to enhance productivity by reducing inefficiencies. From a standards viewpoint, we need to focus on the projects that are most likely to have the broadest adoption, where the savings are greatest, and that will be easiest to implement. These are the projects that will have the greatest impact on distribution of content, which is good for publishers, libraries, and ultimately the end users we all serve.

Todd Carpenter (tcarpenter@niso.org, @TAC_NISO) is the Managing Director of the National Information Standards Organization (NISO), a nonprofit membership association that fosters the development and maintenance of standards that facilitate the creation, persistent management, and effective interchange of information used in publishing, research, and learning. Throughout his career, Todd has served in a variety of roles with organizations that connected the publisher and library communities. Prior to joining NISO, Todd had been Director of Business Development with BioOne, an aggregator of online journals in the biological sciences. He has also held management positions at The Johns Hopkins University Press, the Energy Intelligence Group, and The Haworth Press. Todd is a graduate of Syracuse University and holds a masters degree from the Johns Hopkins University.

Notes

Sharon Farb, “Libraries, licensing and the challenge of stewardship,” First Monday, 11, no. 7 (July 3, 2006). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1364/1283.

Karen Calhoun, “The Changing Nature of the Catalog and its Integration with Other Discovery Tools,” prepared for the Library of Congress, 2006. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/calhoun-report-final.pdf.

David S. H. Rosenthal, Thomas S. Robertson, et al., “Requirements for Digital Preservation Systems: A Bottom-Up Approach.” arXiv:cs/0509018v2.

Timothy D. Jewell, et al., Electronic Resource Management Report of the DLF ERM Initiative. Washington, D.C.: Digital Library Federation, 2004. http://old.diglib.org/pubs/dlf102/.

Oliver Pesch. “Gathering Data: What Data Do I Need and Where Can I Find It?” http://niso.kavi.com/news/events/niso/past/erm07/erm07pesch.pps.

Oliver Pesch. Slide from: “The Third S: Subscriptions to Electronic Resources.” Presented at NISO Webinar: The Three S's of Electronic Resource Management, January, 12, 2011. http://www.niso.org/apps/group_public/download.php/5594/3swebinar_jan11.pdf.

COUNTER (Counting Online Usage of Networked Electronic Resources) is “an international initiative serving librarians, publishers and intermediaries by setting standards that facilitate the recording and reporting of online usage statistics in a consistent, credible and compatible way.” http://www.projectcounter.org/.

Portico is a community-supported, digital archive. http://www.portico.org/digital-preservation/.

LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe), based at Stanford University Libraries, “is an international community initiative that provides libraries with digital preservation tools and support so that they can easily and inexpensively collect and preserve their own copies of authorized e-content.” http://lockss.stanford.edu/lockss/Home.

SERU: A Shared Electronic Resource Understanding, NISO RP-7-2008. Baltimore, MD: NISO, 2008. http://www.niso.org/workrooms/seru.

The OpenURL Framework for Context-Sensitive Services, ANSI/NISO Z39.88- 2004 (R2010). Bethesda, MD: NISO, 2004 (reaffirmed 2010). http://www.niso.org/standards/z39-88-2004/.

The Standardized Usage Statistics Harvesting Protocol, ANSI/NISO Z39.93-2007. Baltimore, MD: NISO, 2007. http://www.niso.org/workrooms/sushi.

KBART: Knowledge Bases and Related Tools, NISO RP-9-2010. Bethesda, MD: NISO, 2010. http://www.niso.org/workrooms/kbart.

ESPReSSO: Establishing Suggested Practices Regarding Single Sign-On [webpage]. http://www.niso.org/workrooms/sso.

I2 (Institutional Identifiers) [webpage]. http://www.niso.org/workrooms/i2.

EDItEUR is the international group coordinating development of the standards infrastructure for electronic commerce in the book, e-book, and serials sectors. http://www.editeur.org/.

The United Kingdom Serials Group’s (UKSG) “mission is to connect the information community and encourage the exchange of ideas on scholarly communication.” http://www.uksg.org/.

The Book Industry Study Group (BISG) “is the leading U.S. book trade association for supply chain standards, research, and best practices.” http://www.bisg.org/.

ONIX for Publications Licenses (ONIX-PL) [webpage]. http://www.editeur.org/21/ONIX-PL/.

Cost of Resource Exchange (CORE) Protocol, NISO RP-10-2010. Baltimore, MD: NISO, 2010. http://www.niso.org/workrooms/core.

COUNTER Code of Practice for Journals and Databases, Release 3. COUNTER, August 2008 (effective August 31, 2009). http://www.projectcounter.org/code_practice.html.

SERU Registry [webpage]. http://www.niso.org/workrooms/seru/registry/.