Academic Search Engine Spam and Google Scholar's Resilience Against it

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

6 Results

6.1 Websites Google Scholar crawled

Google Scholar did not index our PDF files from mendeley.com and researchgate.com, although other PDFs from those websites are indexed by Google Scholar. PDFs from sciplore.org, beel.org and academia.edu were indexed as well as PDFs from the university’s Web space.

6.2 Spamming while writing a real article

While writing one of our real papers (Beel and Gipp 2009b), and before it was published, we added words in white color to the first page (see Figure 2). In addition, we added several words in a layer behind the original text (see Figure 3). Finally, a vector graphic, a type of picture that can be searched and is machine readable, was inserted. This vector graphic was also placed behind the original text, and contained white text in a tiny font size (see Figure 4).

The paper then was submitted and accepted for a conference, published by IEEE, and included in IEEE Xplore. We did not let IEEE know what we were doing, and the invisible text was not discovered. About two months after publication the paper was crawled and indexed by Google Scholar, which included the invisible text. That means users of Google Scholar may find our article when they search for keywords that appear only in the invisible text.

6.3 Modifying an already published article

6.3.1 Content modifications

We modified some articles we had already published and added additional keywords (both visible and invisible) throughout the document. Google indexed all modified PDFs and grouped them with the original ones. That means users of Google Scholar may find these modified articles when they search for the additional keywords. In other words, researchers can make their articles appear for keyword searches the original article would not be considered relevant for.

New keywords were also added to the PDF metadata (title and keyword field). However, Google Scholar did not index the additional metadata.

6.3.2 Bibliography modifications

In several existing articles we added new references to the bibliography. Some pointed to articles that were more recent than the original article. These modified articles were uploaded to the Web, and Google Scholar indexed all additional references. As a consequence, citation counts and rankings of the cited articles increased.

That means researchers could easily increase citation counts and rankings of their articles by modifying existing article (and not necessarily their own). This way a researcher could also increase visibility of his articles. He could modify one of his own articles, add references to the bibliography, and the newly cited authors would then probably pay attention to the article.

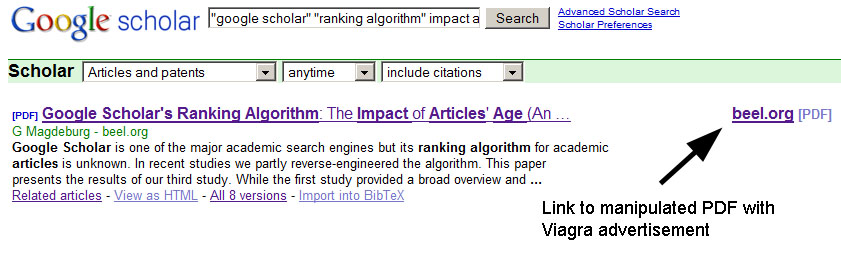

6.3.3 Adding advertisements

We modified one article (Beel and Gipp 2009b) and placed Viagra advertisement in it, including a clickable link to the corresponding website (see Figure 5). After a few weeks Google Scholar indexed the PDF file and grouped it with the already indexed files.

That means users of Google Scholar interested in the full text of our research article (Beel and Gipp 2009b), might download the manipulated PDF containing the Viagra advertisement and we—if we were real spammers—could generate revenue from the researchers visiting the advertised website.

6.4 Publishing completely new papers

So far, we had modified only existing papers. Google Scholar already knew the articles’ metadata—title and author, for instance—when it was indexing the manipulated PDFs.

We also made Google Scholar index papers that were never officially published.

6.4.1 Publishing nonsensical papers

Using the random paper generator SciGen (Stribling et al. 2005), we created six random research papers. These papers consisted of completely nonsensical text and bibliography. Only one real reference (Alcala et al. 2004) was added. We created a homepage for a non-existent researcher and offered the six created papers on this homepage for download. The homepage was uploaded to the Web space OvGU.de, and linked by one of our own homepages, so the Google Scholar crawler could find it.

Although Google Web Search indexed the homepage and PDFs after three weeks, Google Scholar did not initially index the PDF files.

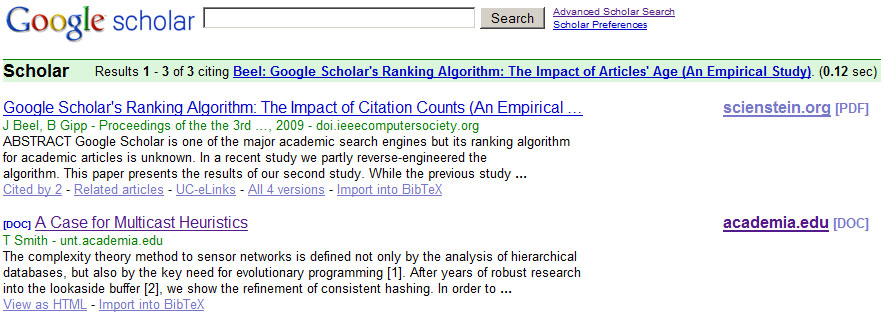

We then uploaded one of the papers to Academia.edu. After two months Google Scholar indexed the paper from Academia.edu (see Figure 6) and from the university website as well, and ranking of the cited articles increased.

Apparently, Google Scholar has different trust levels for different websites. It indexes unknown articles from the trusted websites, but indexes only known articles from untrusted websites. In this case, academia.edu seems to be considered trustworthy. Each article on that platform is indexed by Google Scholar. It appears that once an article is indexed from Academia.edu, other PDFs of that article are indexed, even from websites Google Scholar does not consider trustworthy.

6.4.2 Nonsensical text as real book

Recently created print-on-demand publishers such as Lulu, Createspace, and Grin can publish a book, including ISBN, free, within minutes. We analyzed whether a group of fake articles published as a real book would be indexed by Google Scholar.

We created fourteen new fake articles with SciGen (Stribling et al. 2005). We replaced the nonsense bibliography of each article with real references. We bundled the fourteen articles in a single document and published this document as a book with the publisher Grin (Beel 2009). After a few weeks, the book was indexed by Google Books, and some weeks later by Google Scholar. All fourteen articles can be found on Google Scholar and their citations are displayed on Google Scholar too. That means citation counts and rankings of around a hundred articles increased because the fourteen fake papers cited these articles. Also the (non-existent) authors are now listed in Google Scholar.

6.4.3 Publishing new articles based on real articles (duplicate spam)

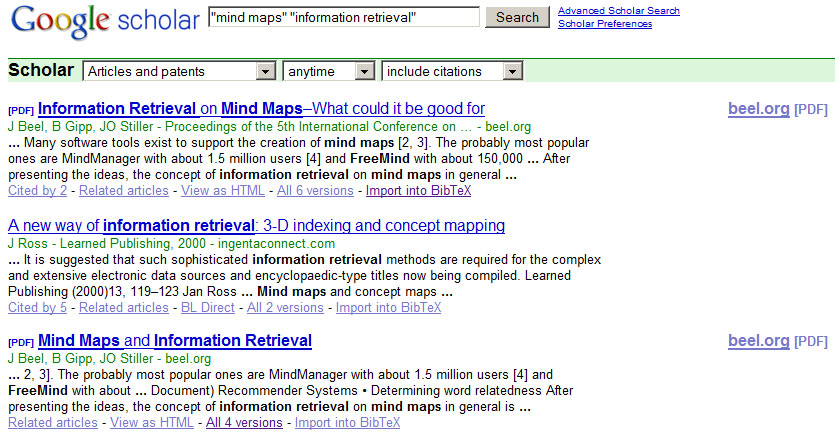

In 2009 we published an article about how data retrieved from mind maps could enhance search applications (Beel et al. 2009). It was titled ‘Information retrieval on mind maps—what could it be good for?’ We took this article, changed the title to ‘Mind Maps and Information Retrieval’ and replaced some references. The body text was not changed. After uploading the article to the Web, Google Scholar indexed it as a completely new article.

That means when users of Google Scholar search for ‘mind maps’ and ‘information retrieval’ the result set displays not only the original article, but the modified one as well (see Figure 11). Accordingly, the probability that users will read the article increases.

Something similar happened with a book we published about rewarding project teams (Beel 2007). Google Scholar indexed the original print version, which is also available on Google Books. When we posted the PDF on the book’s website, http://team-rewards.de, Google Scholar indexed it as a new article. Differences between the documents, each about 100 pages, are minimal. However, as Figure 8 shows, Google Scholar has misidentified the title. The correct title is on Google Books: ‘Project Team Rewards: Rewarding and Motivating your Project Team’. The PDF’s title was incorrectly identified as ‘Project Team Rewards’.

As a consequence of this misidentification, both documents are displayed for searches for the term ‘project team rewards’ or other similar terms. In addition, the cited articles all received two citations because the original book and the PDF from the website were indexed separately.

Based on these results, it seems that Google Scholar is using only a document’s title to distinguish documents. If titles differ, documents are considered different.

6.5 Miscellaneous

In our research we saw some issues that might be relevant in evaluating Google Scholar’s ability to handle spam and its reliability for citations counts.

6.5.1 Value of citations

Google Scholar indexes documents other than peer-reviewed articles. For instance, Google Scholar has indexed 4,530 PowerPoint presentations[6] and 397,000 Microsoft Word documents. It has indexed a Master thesis proposal from one of our students and probably many proposals more. Citations in all these documents are counted[7]. It is apparent that a citation from a PowerPoint presentation or thesis proposal has less value than a citation in a peer reviewed academic article. However, Google does not distinguish on its website between these different origins of citations[8].

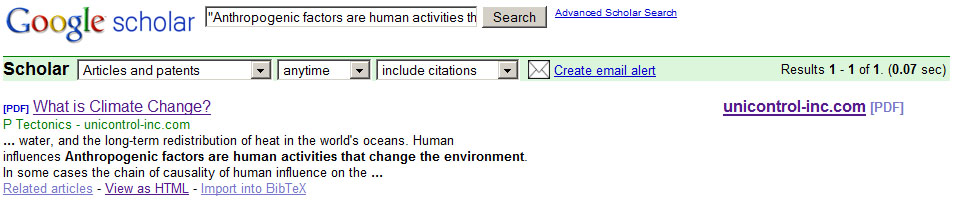

6.5.2 Wikipedia articles on third party websites

Google Scholar indexes Wikipedia articles when the article is available as PDF on a third party website. For instance, the Wikipedia article on climate change[9] is also available as a PDF on the website http://unicontrol-inc.com (with a different title). Google Scholar has indexed this PDF (see Figure 9) and counted its references.

That means, again, that not all citations on Google Scholar are what we call ‘full-value’ citations. More importantly, researchers could easily perform academic search engine spam just by citing their papers in Wikipedia articles, creating a PDF of the Wikipedia article, and uploading the PDF to the Web.

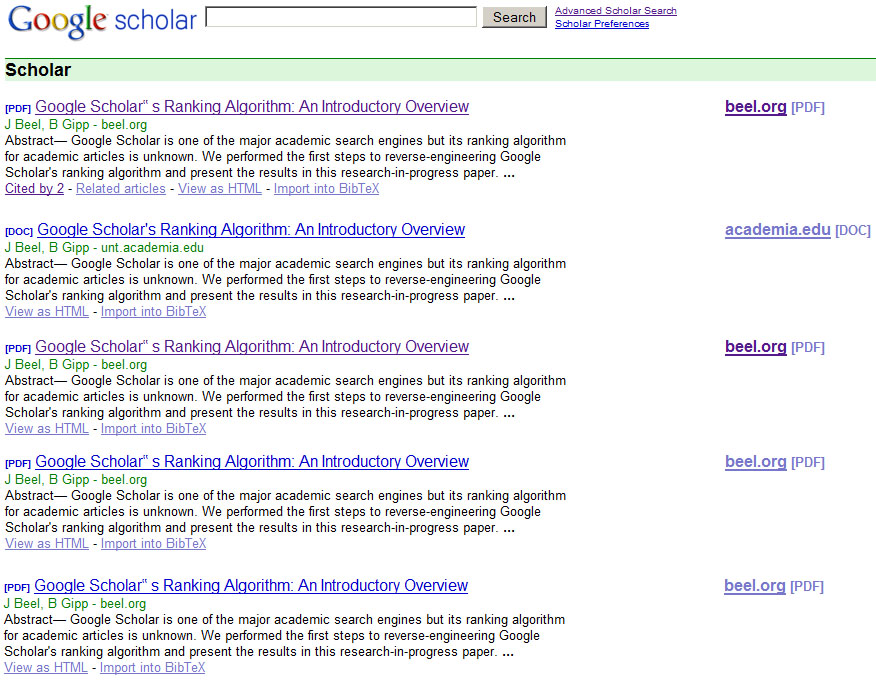

6.5.3 PDF duplicates / PDF hijacking

Google Scholar indexes identical PDF files that have different URLs separately, even if they are on the same server. In case of our article ‘Google Scholar’s Ranking Algorithm: An Introductory Overview’, four PDFs on the domain beel.org (see Figure 10) were all indexed. Google even considers the same PDF with same URL—once with and once without www—as different.

That means a spammer could upload the same PDF several times to the same Web page and all PDFs would be displayed on Google Scholar. Consequently, the probability that a user downloads the manipulated PDF would increase.

The ranking of grouped PDFs depends mainly on the file date—newer files are listed higher. That means spammers publishing modified versions of an article most likely will see their manipulated PDF as the primary download link for an article. This was also the case in our test with the manipulated PDF containing Viagra advertisement. The manipulated PDF is the most current PDF and displayed as primary download link (see Figure 11).

A similar practice is known from Web spam. ‘Page hijacking’ describes the practice that spammers create Web pages (with advertisements, malicious code, etc.) similar to a popular website. Under some circumstances Google identifies the duplicate as the original Web page and displays the duplicates’ website as the primary search result.

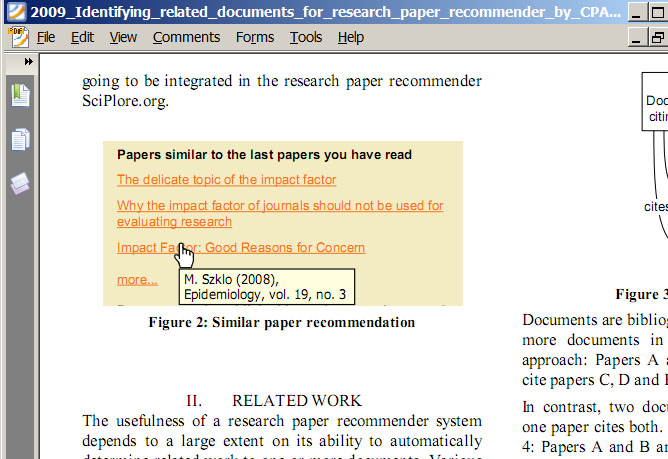

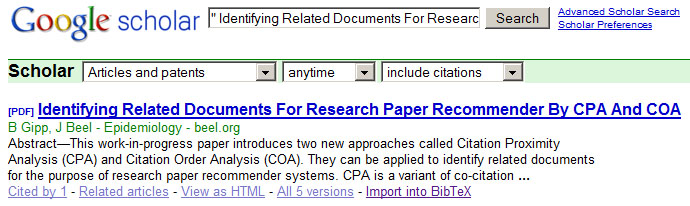

6.5.4 Misidentification of journal name

By coincidence we realized that it is possible to manipulate the journal name Google Scholar anticipates as the publishing journal of an article. One of our papers (Gipp and Beel 2009) includes a vector graphic on the second page that illustrates how recommendations are made on our website http://sciplore.org. This vector graphic includes bibliographic information, among others ‘Epidemiology, vol. 19, no. 3’ (see Figure 12 for a screenshot of that PDF and the vector graphic).

Interestingly, Google Scholar used this bibliographic information as the name of the journal our article was published in (although it was not). A search on Google Scholar for our article shows the article as being published in Epidemiology, a reputable journal by the publisher JSTOR (see Figure 13).

Apparently, Google Scholar is using text within an article to identify the article’s publishing journal. This could be used by spammers to make their papers appear as if they were being published in reputable journals.