Opening Up Institutional Repositories: Social Construction of Innovation in Scholarly Communication

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Social Construction of Technology

Social construction of technology as a theoretical framework provides a model to study the social context of technological innovation. Its key assumption is that innovation is a complex process of co-construction in which technology and users negotiate the meaning of new technological artifacts (Pinch and Bijker, 1987). Central to social construction of technology is the concept that there are choices inherent in both the design of technologies and their appropriation by relevant groups. Technology deployment cannot be understood without comprehending how a specific technology is embedded in its social context.

There are several studies based on the social construction of technology that illustrate the implementation of the framework on emerging information and communication technologies to support a richer analysis of outcomes through the inclusion of broader social, cultural, and political factors (Dayton, 2006; Cooley, 2004; Jackson, Poole, and Kuhn, 2002; Mitev, 2000). An inspiring example is set by Bohlin (2004) with his use of the social construction methodology in analyzing the current transformation in scholarly communication with a focus on e-print repositories. He examines how arXiv[4] as a digital repository is embraced by the high-energy physics community.

The following discussion involves the application of the three key social construction concepts to shed light on the negotiation process involved in IR development and adoption. Analyzing IRs from the perspectives of relevant social groups, interpretative flexibility, and stabilization uncovers a range of social and cultural contingencies that are crucial in determining the acceptance of the application by the scholarly community.

Relevant Social Groups

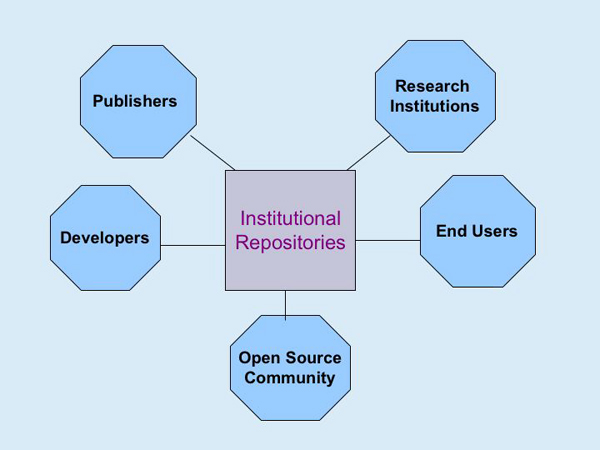

At the foundation of the explanatory framework of the social construction of technology is the concept of relevant social groups, which share a particular set of meanings about a technology or an information system. In the case of IRs, the relevant social groups include a wide range of stakeholders who have different interpretations of the application based on their needs, roles, goals, values, and motivations. The stakeholders also vary in their ability to influence the development, application, and acceptance of IR applications. It is important to note that this paper identifies only the key stakeholders, as the goal is to demonstrate the interpretative flexibility rather than providing a full analysis.[5] As shown in Figure 3, the key relevant groups include the developers, research institutions, users, open source community, and publishers. These groups are described in Table 1.

| DEVELOPERS | Developers (information technologists and librarians) gather user requirements and develop, test, and maintain the system code. |

| RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS | Research institutions such as libraries assume the service provider role with the dual responsibility of installing and maintaining IR systems and managing their deployment in their organizations through outreach and training programs. |

| USERS | Users encompass a wide range of academic practitioners including faculty, researchers, and graduate students. They are “consumers of the service” both as contributors of scholarly outputs for archiving and as users of information deposited in the IR. |

| OPEN SOURCE COMMUNITY | Programmers and systems analysts who are interested in contributing to public open access software development efforts to support collaborative application development and maintenance. |

| PUBLISHERS | Publishers, including learned societies, commercial publishers, individual authors, and university presses, who have been in the business of publishing through formal publication mechanisms (e.g., journals, books). This group also includes those who are now in a position to be publishers due to the opening of the publishing market to a wider range of participants.[6] |

Interpretative Flexibility and Technological Frames

According to the social construction of technology theory, technologies are culturally constructed and interpreted. The interpretative flexibility notion denotes both variations in understanding of a technology and the flexibility of the design process. Bijker’s (1987) concept of a technological frame refers to the concepts and techniques employed by a community for addressing needs, and is intended to apply to the interactions among various actors. Technological frame denotes the commonality of perception and approach in a particular group and is composed of elements such as tacit knowledge, challenges faced, norms, technical skills, institutional policies, and practices. It provides the context in which a new technology is interpreted.

There is growing evidence that adoption of IRs by scholars is slow and the perceived benefits are not immediately obvious to the scholarly community (Ferreira et al., 2008; Davis and Connelly, 2007; Thomas and McDonald, 2007; Chan, 2004). Although there is a common desire to facilitate and enhance scholarly communication, the following examples based on DSpace institutional repository software[7] demonstrate the variations in the IR stakeholders’ technological frames that present reverse salients[8] in widespread adoption of the technology.

1. IR as a Tool for Institutional Asset Management

The developers have a unified vision of providing a way to manage and preserve research materials and publications in a professionally maintained repository to enable greater visibility and accessibility over time. Some among them also aim to promote open-source publishing systems in order to correct the imbalance[9] in the scholarly communication environment. They perceive the benefits of IRs to include scholars’ ability to get their research results out quickly, reaching a worldwide audience, archiving course materials, and keeping track of their publications (Smith et al., 2003).

DSpace, as the pioneering and currently the most common IR software, provides an illustrative example of the developers’ technological frame. DSpace was developed in an academic context with the notion of building communities that represent different academic departments, research centers, labs, etc. (see Figure 1 showing Cornell’s DSpace-based installation). The goal was to manage academic assets based on an information model that represents an institution’s organizational structure. The DSpace developers emphasized the local community-building aspects of DSpace and made a deliberate decision to use the term institutional repositories in representing and promoting the service category.

However, some faculty members are put off by the concept of institutional and may hesitate to share their documents on an open access system run by an institution. The need for supporting inter-organizational networks is perceived differently by developers and users of DSpace. While the library community appreciates institutional networks, academics feel closer to their own disciplinary networks. In my interviews, faculty members told me that at the heart of their reaction are concerns about quality (which is an essential criterion for scholarly outputs) and potential copyright infringements. Several faculty members I talked with during my study expressed the need to stay closer to their special communities through networking and information sharing both for professional development and for building reputation. Also, many of them expressed their preference for posting articles on their own Web sites rather than institutional repositories. The separation of practitioners into disciplines with distinct cultures and needs has kept scholars from converging and advocating more open and cost-efficient information-sharing methods (King et al., 2006).

2. DSpace as an Open Access Tool

It is important to note that the DSpace development community has had a political agenda too. The digital library community advocated for alternative channels of scholarly communication because of what they characterized as the “scholarly communication crisis,” the increasing publication prices, prohibitive copyright implementations, and commercial publishers’ lack of long-term management strategies for digital content. DSpace has been positioned as a new strategy to influence the existing publication models and to present an alternative mode to control the economic threats perceived by the library community from commercial publishers (Chan, 2004). However, most faculty members are not as much concerned about the library community’s scholarly communication crisis and do not perceive an immediate need to modify the existing scholarly communication system (Troll Covey, 2007).[10] Some scholars see open access as undermining the traditional scholarly communication system and eroding prestige that is guarded and reinforced by scholarly publishing and university tenure boards (Kennan and Cecez-Keemanovic, 2007).

Based on interviews and ethnographic observations involving faculty and researchers, Foster and Gibbons (2005) conclude that IRs fail to appear compelling and useful to the authors and owners of scholarly content (users).[11] Even the terminology used in promoting DSpace (IR, digital preservation, metadata, open-access, interoperability) presents confusing concepts for faculty and is seen as professional jargon. The benefits of IRs thus far seem to be very persuasive only to hosting institutions such as research libraries. Kim’s (2007) preliminary survey of 67 professors concluded that faculty members who intended to contribute to the IR in the future agreed more strongly with of the concept of open access. The pilot study also pointed out that the influence of grant funders lowers faculty motivation for IR contribution.

Boczkowski’s[12] 2006 study of the cultural and political dynamics in the adoption of institutional repositories revealed that librarians and academics approach the technology from different points of view. While the information science practitioners such as librarians are trying to drive change, the more powerful academic community is refusing to modify their existing practices. The library community has built a solution based on a perceived problem (scholarly communication crises); but because the academics do not observe a problem that needs to be fixed, they are reluctant to adopt practices and policies imposed on them by others in the institution.

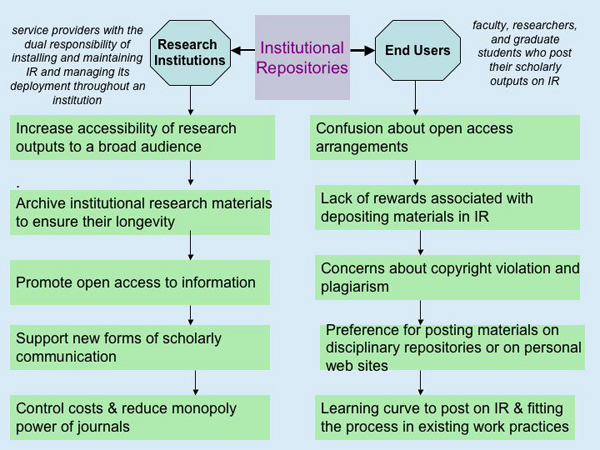

Figure 4 lays out the perceptions of the two relevant groups in regard to the IR’s role in facilitating, sharing, and archiving scholarly materials. The discrepant interpretations of relevant groups inevitably create a natural tension in the development and deployment efforts because of differences in expectations. Also, because the technology is new and still changing, the technological frameworks of end users appear to be evolving and there are not yet any significant alignments among different frames.

Stabilization and Closure

According to social construction theorists, as a technology such as IR evolves, the interpretation and design flexibility goes through a closure process as it stabilizes. The stabilization may occur through a rhetoric closure in which the groups see the problem as solved when the technology addresses a number of stakeholders’ needs. Alternatively, closure may occur due to the redefinition of the problem or appearance of a new problem that needs to be solved through design (Pinch and Bijker, 1987). Closure implies that some particular interpretation dominates. Nevertheless, closure is not permanent; the process may be reopened as existing social groups are transformed or new stakeholders are introduced.

Although applying social construction of technology theory to stabilized initiatives seems to be the norm, it is not unusual to apply the theory to an open-ended and contingent process such as IR development and deployment.[13] Pinch and Bijker (1987) propose that the theory framework should apply to open and ongoing technological controversies as well as stabilized ones. The value of using social construction theory before the stabilization process is the opportunity to analyze the social negotiations in a predictive rather than purely descriptive manner. Diagnosing the gaps among the views held by major stakeholders leads to a more realistic assessment of factors involved in the adoption of a technology, and some of those factors can be useful to ongoing design and promotion processes.

Relevant social groups not only characterize technological problems in their own ways, but they also assign success or failure to particular technical systems differently based on how their needs are met (Cooley, 2004). In the case of scholarly communication technologies, new systems and standards continue to appear, creating a dynamic market. Some argue that sooner or later open access will be the predominant form of scholarly information dissemination and IRs will prevail. However, social construction of technology theory contests such deterministic claims and states that the utility of a new technology depends upon cultural patterns and social conventions of multiple groups (Bohlin, 2004). Even if IRs as systems and services have the potential of solving the problems, they will not be widely used if academics do not agree that there is a problem and that IRs can address it.