Crossroads: A New Paradigm for Electronically Researching Primary Source Documents

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

At Oxford University there is a particularly harrowing final examination called the “prescribed text.” This comes in the form of a dozen or so very brief abstracts of passages from a philosophical text. The text is selected by the examiners and announced three years prior to the exam, but the chosen passages, naturally, are not announced ahead of time. Examinees are required not only to explicate the significance of the chosen passages but also to reference as many of the most influential published reflections on the passages as they can. The text is typically voluminous, on the order of John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which means that the student must not only think hard about the meaning and implications of hundreds of passages, but also must find and absorb as many influential reactions to them as possible. There are, of course, myriads of such reflections, but they are scattered throughout thousands of monographs and journals. Even with the extensive resources of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, the exam presents students with a most daunting challenge, made even more difficult because in many subjects hundreds of students take the same examination, and are therefore looking for the same material at the same time. I took such an exam some thirty years ago (and got assigned Locke’s Essay, of course), and what I needed then is still needed today—an “edition” of the prescribed text that is so deeply annotated that everything essential is right there, scribbled in the margins, as it were, of every passage. In the Spring of 2006, I and my colleagues at Readex assembled a team of academic advisors, product managers, and IT staff to tackle this challenge in the much larger research environment of the Archive of Americana online database. Our goal was to allow scholars to scribble in the margins of every text printed in early America. The result of our efforts is called “Crossroads.” The Archive of Americana is Readex’s online database of early American imprints, newspapers, government documents, and ephemera. It is huge, with some 73,000 early American imprints (mostly monographs and pamphlets) from the Evans and Shaw-Shoemaker bibliographies for the years 1639–1819; tens of millions of articles from 2,000+ newspapers, based on the Brigham and Gregory bibliographies and covering the period 1690–1923; government documents centering around the U.S. Congressional Serial Set (which will eventually include the 13,800 volumes and 12 million pages of publications of the U.S. Congress for 1817–1980—currently it is completed to 1941); and the American Ephemera collection of the American Antiquarian Society, the largest of its kind in the United States.

The goal of the Archive of Americana is to provide, under one roof, the most comprehensive collection of American research materials that can be found and organized. It is the scope of the collection that makes it the ideal complement to Crossroads. Crossroads basically gives scholars a single way to interact with any page or article in this vast collection, and gives them credit for their annotations and comments, or links to other items or comments, all of which is permanently archived. We hope that in time Crossroads will evolve into the ultimate “prescribed text,” providing precisely the kind of rich, item-level contextual scholarship that I needed so desperately 30 years ago.

In the two years we spent researching and planning this project we learned that the need for such a system extends far beyond the “prescribed text.” Starting in the spring of 2006, we consulted a number of scholars who make extensive use of digital resources.[1] We also talked to dozens of scholars and teachers and created a list of specific “use cases”—tasks that we found to be central to their scholarly routines. These became the key elements for further market research and design. In short, the input of these advisors strongly supported the archiving of scholarly contributions, but they pointed to another need that Crossroads could also be designed to meet: a better platform for scholarly collaboration.

Scholarly collaboration can range from interactive classroom projects to international research projects. A good example of the former is Michael Clark’s Core Humanities Course at the University of California, Irvine, in which more than a thousand students simultaneously study and interact with a single digital syllabus: http://www.hnet.uci.edu/mclark/HumCore/CoreF2005/WebCoreF05/F05TwainLec.htm

An example of a broader project is that of food historian and professor Louis Grivetti at the University of California, Davis. Grivetti coordinates the efforts of dozens of scholars around the world who are researching the history of chocolate. At Brown University, Vika Zafrin, director of the Virtual Humanities Lab, was in 2003–7 leading a team of editors from many universities in the U.S. and Europe who were creating digital annotations to Bocaccio’s Decameron and other early texts (http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Italian_Studies/dweb/project/credits.shtml). Also at Brown, George Landow created the Victorian Web, a database that has burgeoned to more than 36,000 digital texts and that on last count was garnering up to 14 million page views per month: http://www.victorianweb.org/. At the national level, the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) in the United Kingdom has teamed up with the British Academy to create the Early Modern Texts Forum, a highly interactive online collaboration that could link thousands of British Humanities scholars to a joint set of texts and communications: http://www.earlymoderntexts.org/.

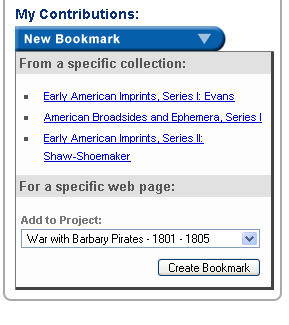

Convinced that such collaborative scholarship—once far more common in the sciences—will play an increasing role in the study of the Humanities, we added features to Crossroads that would simplify the creation and organization of such projects. We didn’t want to create another course management tool, however. We are well aware of how such tools as Blackboard and Sakai are used, and we recognize their limitations—chief among them the fact that when course management systems are deployed, access is limited to use by the single institution deploying it, which prevents many forms of collaborative research. Crossroads has no such limitation. In addition, while course management tools can point to content and even import content to some extent (provided the source of the content provides it in an “importable” format), they are severely limited by barriers to referencing content in a granular way. For example, while it is possible to include, say, an OpenURL[2] link to an entire digital document, if the pertinent reference is to a specific page in the document, that information must be specified in the text of the reference, and users clicking the link will be on their own in figuring out how to navigate to that specific page (i.e. “This link is to a book containing a passage about XYZ on page N. After clicking on this link, click on Table of Contents, scroll down...”). Similarly, any contextual information (e.g. “This paragraph is important because...”) must be conveyed in the text surrounding the link and users must try to hold that information in their thoughts while they find their way to that passage, since there is no way for those annotations to appear in the “margins” of the page. With Crossroads, users “bookmark” content down to the page or article level, and in doing so get their own virtual copy of the item where they can add content in the “margins.” We think this level of content-centricity gets users much closer to what they are actually trying to accomplish.

What competitors does Crossroads have? We are unaware of any tool that overlaps with Crossroads in more than a few areas of functionality. While there are numerous tagging/bookmarking tools, such as Del.icio.us, they generally function as a single giant “universe” of tags. That has interesting benefits, such as fostering serendipitous discovery. It also creates some very thorny problems, such as researchers in unrelated disciplines using the same tag for very different purposes. Crossroads offers the concept of “projects” in which each project can have its own universe of tags, letting researchers create and manage their own vocabulary for organizing their references without having to worry about crosstalk from other research efforts. Yet, users can still search across projects, so Crossroads also offers the benefit of serendipitous discovery.

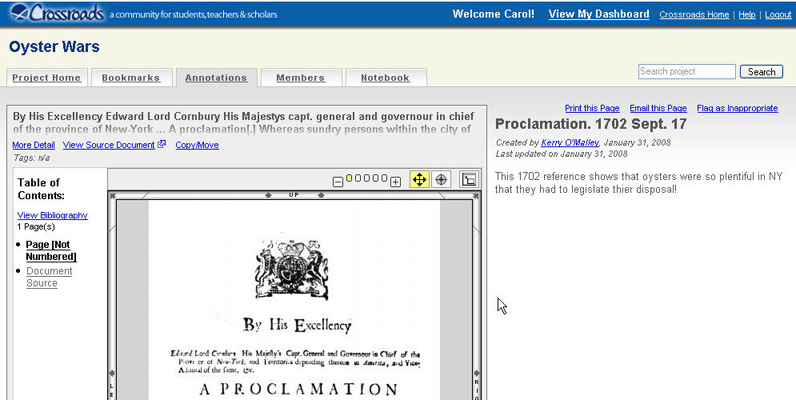

Wikis are another popular tool for enabling groups of users to collaborate on creating and editing content. However, we found wikis generally to be poorly suited for discussions or tight integration with content; they often require cumbersome steps or technical skills beyond what we felt should be expected of our audience. We found blogs, too, to be lacking in many of these same areas. And in all of these cases, what we found was that even if we were to build Crossroads from these individual components, it still wouldn’t add up to a “community of communities” in the way that Crossroads is, with each user or group of users creating their own “projects” expressed as organized collections of references with annotations and discussions. The core differentiators between Crossroads and all of these are content-centricity: scholars can scribble in the margins, metaphorically, in a collaborative environment and organize the content they want through tags. In the illustration below Kerry O’Malley, a Readex colleague who was involved in early testing, has chosen a proclamation, annotated it in the margin, and made it available for other researchers to study and annotate themselves. His bookmark is part of the “Oyster Wars” project he created (see the upper left corner of the screenshot).

Kerry O’Malley and all others who contribute annotations and comments own the copyright to their words. In the Terms of Use section of the application, we make it clear that the authors of all contributions hold copyright to them. It is also stipulated that for annotations and comments that a contributor chooses to make public in Crossroads, Readex holds the online distribution rights to the contribution as part of the Crossroads database.

Crossroads took about two years to build; the first 12 months were devoted to brainstorming with the advisory board, consulting a wide group of scholars, holding focus groups, and researching available products and technologies. In a crucial meeting in November, 2006, we finalized the concept. We identified the functionalities that we expected to provide, such as tagging, creating annotations, user profiles, and online discussions. Then we asked ourselves why we thought users would want this functionality and what problems these solutions might address. That led to a short list of “use case vignettes”[3] that described the kinds of outcomes users would expect. (We used this list as a touchstone throughout the design and development portion of the project.) With those in mind, we walked through how those tasks are currently being accomplished, what the ideal way might look like, what the obstacles were to achieving the ideal, and how we might be able to improve things. Some of the key conclusions from this meeting included:

Annotations needed to be made to “virtual copies” of documents, not the digital “originals” themselves. Imagine all the annotations made to Thomas Paine’s Common Sense from all of the scholars with their various purposes appearing on the same display of the document at once: it would be chaos. While there needed to be a way for users to discover all of the annotations to a particular document, it would be important for individuals or groups to have their own annotations on their own virtual copy of the document.

Annotations and content references needed to be as granular as possible. While referring to an entire book is sometimes desirable, often it is more desirable to refer to a chapter, page, or even part of a page. This posed some significant technical challenges, since it requires having persistent identifiers not only for whole documents, but for parts of documents.

Users would need one or more “homes” for their virtual copies of documents and their associated annotations. As their collection of items grew, they’d need to organize them in a way that made sense to them. From this, the concept of “projects” emerged, with tagging as an organizing vehicle.

While we envisioned support for a variety of situations involving collaboration, we also recognized that many users would want tools just for their own work.

We thought that most users would start with simple tasks such as distributing a single annotated document for comment and discussion, not projects and collaborative efforts. We needed to design a system that would make it easy to do the simple things and make the more complex possibilities “discoverable” but otherwise in the background.

There needed to be something besides a searchable, sortable, and browseable list of annotated content to fully represent the outcome for some use cases. Users would need a way to create something like a small Web site in which they could publish their findings or tell a story.

Users would need to incorporate content beyond our own Archive of Americana. While the potential for scholarly exploration within the Archive of Americana content alone is seemingly limitless, many (if not most) individual scholarly efforts cannot be limited to the sources of a single provider.

At that November meeting Ken Dufort, vice president for product development, began white-boarding these conclusions, with editorial input from me, product manager Michelle Harper, and my fellow vice president for new product development August A. Imholtz Jr. We had technological and design input from a team that included Carol Forsythe (who became the leader of the build team), Matt Axsom, Nathan Schmidt, and Sandra Davern. Later in the project, a number of other NewsBank/Readex staff members got deeply involved, including the core developers: Dan Law, Ben Caulfield, and Dave Perrin.

We came away from the meeting with a solid concept, but one that presented us with some significant challenges. One of these was the necessity of re-processing all of the Archive of Americana data to support highly granular persistent links, or URLs,[4] at the page level for monographs and at the article level for newspapers. Another was the “build vs. buy” question for many required features, always a controversy in the ever-evolving world of software. We also faced the difficulty of enabling Crossroads users to link out to external databases. These challenges were tackled in early 2007 and Crossroads was built in the fall.

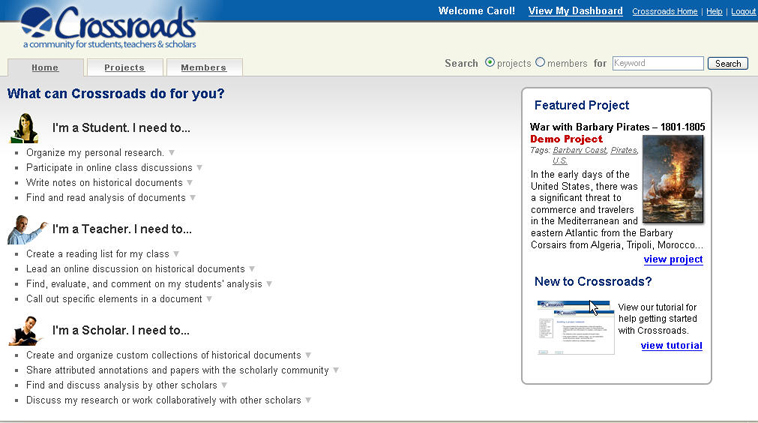

The key features of Crossroads are different for students, faculty, and advanced researchers.

Students need to:

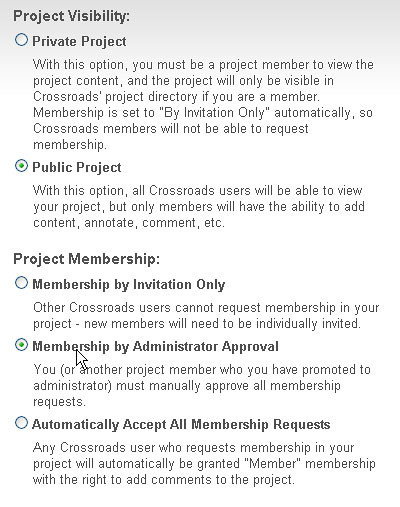

- Organize personal research: One of the foundational elements of Crossroads is the concept of a “project.” A project can be as simple as a single annotation or as complex as a large class or multi-institutional collaboration. Projects can be created by anyone, and they can be kept private or made publicly available. By setting up multiple projects, students can keep their work organized by classes or topic. They can add historical documents to these projects by bookmarking pages from Readex collections or any other collection or Web page that has its own dedicated (persistent) URL. They can tag their bookmarks to make it easy to organize and find their research.

- Participate in online class discussions: For a class project, students can contribute to the discussion by commenting on observations and conclusions drawn by fellow students or the class instructor, or both.

- Write notes on historical documents: From quick personal research notes to in-depth annotations that students may want to share with academic world at large, students can write annotations that can be displayed alongside the source document for easy reference. (They do not clutter up every page view, however; there is simply a symbol on each page to show that an annotation is available; clicking on the symbol opens the annotations in chronological order, last first.)

- Find and read analyses of documents: Students may need to find other projects or project members who are working on topics of interest to them, and read the documents that they have collected and the annotations they have created. Students can also indicate their interest in collaborating by requesting membership in such projects.

Faculty members need to:

- Create a reading list with live links to the assigned documents: Instructors can add documents to a class project by bookmarking pages from Readex historical collections or any other online collection or webpage with a persistent URL. Any annotations or comments added by the faculty members are visible alongside the bookmarked content when users view it. Tags allow instructors to organize their reading lists by topics or keywords, making it easier to navigate project research.

- Lead an online discussion about historical documents: By bookmarking and annotating historical documents that they may want a class to read, instructors can provide the class with both a place to examine these resources and the tools they need to comment on and discuss them. As the project administrator, the instructor will also have the tools needed to moderate the discussion and enforce civility and good scholarship.

- Find, evaluate, and comment on students’ analysis: Instructors can search or browse their students’ contributions—bookmarks, annotations, and comments—to evaluate their work and participation. They can also post comments or criticism and participate in online discussions surrounding this work.

- Highlight specific elements in a document: When an instructor needs to quickly point out an important point or provide a line-by-line analysis of a work, he or she must have the tools to annotate the documents that are added to class projects. In Crossroads, these annotations are displayed alongside the source document for easy reference by students.

Advanced researchers need to:

- Create and organize custom collections of historical documents: When a scholar sets up a research project in Crossroads, he or she can create a custom collection of historical documents by bookmarking pages from Readex collections or any other collection or webpage with a persistent URL. They can also tag their bookmarks with their own index terms, to quickly and easily organize them and find them later.

- Share annotations and papers with the scholarly community: Whether a researcher is pointing out the context and significance of a document or conducting an exhaustive line-by-line analysis of a work, his or her attributed annotations are displayed alongside the source document for easy reference by all other scholars, if the researcher so chooses. The conclusions can also be collected and published in the project Notebook, allowing other Crossroads scholars to read, review, and comment on the research.

- Find and discuss analysis by other scholars: Crossroads enables scholars to find other projects or project members who are working on the same research topics, and read their collected documents and their annotations on the topic. If they are interested in discussing their research and methodology, commenting on their sources or conclusions, or reviewing their project Notebook, they simply request membership in the project.

- Discuss research and work collaboratively with other scholars: By finding other Crossroads members who are researching related topics, and inviting them to join their own project at one of several levels (observer only, contributor, editor, fellow administrator, etc.) scholars can encourage open discussion and feedback from their peers.

Lastly, it should be emphasized that scholars may perform all of these tasks in a closed environment if they choose, so that they are observable only by them, or only by them and a class, perhaps, or a select group of colleagues. They can elect to keep it that way, or at some point permit access by scholars at large.

Crossroads is now live, and is functionally linked to three modules of the Archive of Americana: Early American Imprints I and II, and American Broadsides and Ephemera. In the coming months we will add links to Readex’s America’s Historical Newspapers database and the U.S. Congressional Serial Set. To give people an opportunity to explore the teaching and research benefits of Crossroads, we are offering free, unlimited access through the end of the fall 2008 semester. After January 1, 2009, a modest annual fee will be required for continued access. A look at the interface and a more detailed description of Crossroads is available at http://www.readex.com/crossroads/demo.html.

Remmel Nunn is vice president for new product development at Readex, where he leads the strategy and acquisitions team for the “Archive of Americana” online research database. Prior to joining Readex, Remmel was vice president for academic library strategy at Gale. His previous positions include Publisher at Facts on File and Publisher at the Grolier Educational Corporation. Remmel holds an M.Phil. from Columbia University, a B.A. and M.A. from Oxford University, and a B.A. from the University of Arkansas. Remmel, his wife Kate, and his son William live in Croton-On-Hudson, New York. He may be reached at rnunn@newsbank.com.

Notes

These included Michael Clark, Liz Losh, and Sharon Block (all at the University of California, Irvine), Dan O’Donnell (University of Lethbridge), Vika Zafrin (Brown), Raymond Siemens (University of Victoria), Mark Kamrath (University of Central Florida), Meg Meiman (University of Delaware), and John Lavagnino (University of London, King’s College).

“OpenURL” is a NISO and ANSI standard (maintained by OCLC) for linking to resources or services that satisfy information needs. “URL” stands for Uniform Resource Locator.

Use-case vignettes:

- A teacher locates a broadside in American Broadsides & Ephemera and wishes to add a variety of comments calling out specific elements on the page before distributing it to her students.

- A student linguist wishes to conduct a line-by-line analysis of Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” resulting in a fully annotated digital copy of the document that can be viewed by other students and their professor.

- Three researchers from different institutions located around the world are collaborating on the study of the works of a particular author from the Revolutionary War period. Each has a specific list of works for which they’ll be the initial annotator, but all will be able to make or revise annotations on any document. They wish to make their final work visible to others as a Web site.

- In preparation for an upcoming lecture, a history professor wishes to distribute a reading list to her class that includes links to newspaper articles, documents, pages within documents, and Web sites/pages.

- A group of dozens of scholars from around the world are researching the history of chocolate. They wish to collect and organize chocolate-related references in historical content. The result of this effort will be a continually updated, topically organized directory of these references. Referenced content is displayed with any annotations or commentary provided by the scholars “in the margins.”

By “persistent links,” we mean URLs that can be (reasonably) counted on over time to always bring up the referenced content. If you can bookmark it or add it to Favorites in your Web browser and return to it via that mechanism many days or months later, it’s probably “persistent.”