“The Animal Himself”: Tracing the Volk Lincoln Sculptures. Part I

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In the spring of 1860, shortly before he was nominated for the presidency, Abraham Lincoln sat to the sculptor Leonard Wells Volk in Chicago.[1] Volk proceeded to make a plaster cast of the candidate’s face. Lincoln later recalled that making a cast of his face by applying plaster to it until it dried and was taken off was “anything but agreeable.” Yet, with self-deprecating humor, he declared upon seeing Volk’s cast, there is “the animal himself!” Having captured the animal himself, and taken measurements of his head and torso, Volk sculpted a portrait bust which became the centerpiece of his career and a landmark in American sculpture.[2]

Immediately after Lincoln’s nomination, Volk entrained to Springfield where, preparatory to sculpting a full-length statue of Lincoln, he made casts of his hands. Volk also used the occasion to present Mary Lincoln with a cabinet-size bust of her husband. These sculptures—the mask, the bust, and the hands—far more than the full-size statues of Lincoln which Volk completed in 1876 and 1891, gave him, his son Douglas Volk, and many others the models for hundreds of copies [Figure 1].

The purpose of this paper is to set forth the sequence of Leonard Volk’s Lincoln works which, in addition to his many other sculptural projects, engaged his attention for more than three decades. The paper also outlines how Douglas Volk promoted his father’s casts of Lincoln even as he advanced his own career as a painter. This study—a “genealogy” of the Volk Lincoln sculptures—is intended to provide not only a better understanding of their creation but also a check on the misinformation that others have purveyed about reproductions of them.

Leonard Volk was born into a farm family in Wellstown, New York, in 1828. At the age of 16, after rudimentary schooling in several communities, the last being Lanesborough, Massachusetts, he began working as a stonecutter with his father, just as other brothers in a family of twelve had done. They mainly cut stone for buildings and tombstones in upstate New York and western Massachusetts. In 1848, Leonard traveled west to St. Louis, where Cornelius Volk, an older brother, had located. For a time, he worked for James G. Batterson, a Yankee entrepreneur who made a fortune in the stone-cutting and insurance business. Volk cut stone for Batterson for about a year at $50 a month, and he also endeavored to upgrade himself from stonecutter to sculptor. On his own, he sculpted a number of works, including a copy of Joel Tanner Hart’s bust of Henry Clay and medallions for the mausoleum of Maj. Thomas Biddle and his wife. From 1850 until his death in 1895, Volk sculpted more than two hundred statues and statuettes, busts, and cameos, and dozens of copies of many of them. He received one commission after another, both portrait busts and public monuments, not only because he became a competent craftsman, but also because his representations of Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas established his reputation of a sculptor.[3]

In 1852, Volk married Emily Clarissa Barlow, and they moved about—to Galena, back to St. Louis, then up to Rock Island. It was Volk’s good fortune that his wife was a cousin of Judge Douglas. Calling upon them on his political trips to Galena and Rock Island, Douglas urged the Volks to move to Chicago, the more promising city, which they later did. Moreover, Douglas offered to support Volk’s education as a sculptor by sending him to Italy. Thus, in September 1855, Volk crossed the Atlantic, leaving his wife and infant son with relatives in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. During Volk’s absence, the son died and a second son was born and named Stephen Arnold Douglas Volk in honor of his father’s patron. Throughout the younger Volk’s life, he was known simply as Douglas Volk.[4]

Arriving in Rome, Leonard Volk joined a circle of other American sculptors, including Harriet Hosmer (1830–1908), whom he had met in St. Louis, and Thomas Crawford (1814–1857), who advised him to first “learn something of drawing in outline, from the cast or from life,” before “Roman fever” would cause him to undertake a full-scale statue or bust. Volk, however, soon sculpted a bust of his friend Randolph Rogers (1825–1892) and, with American pride, he modeled a statue of Washington, “represented in his youth as having hacked his father’s pear tree.”[5]

In January 1857, Volk returned to America. He and his family settled in Chicago the following summer, and he opened a studio in the Portland Block at the southeast corner of Dearborn and Washington streets. There Douglas sat to him, Volk taking a plaster mask of his patron which he used in making a bust. Volk also created a statuette of Douglas, and, with his assistance, traveled to New York and Washington, D.C., so as to “publish” copies of this work. Advertised as a “Campaign Document,” each bronze copy was sold by Volk or his agents at $40 each, and copies in composition (a plaster aggregate) at $15 each. The statuette, patented on February 14, 1860, sold well among Douglas Democrats.[6]

In 1858, Leonard Volk met Abraham Lincoln. He was introduced by Augustus M. Herrington, who on Judge Douglas’s recommendation briefly served as U.S. Attorney for Northern Illinois. Douglas had invited “Gus” Herrington and Volk to join his campaign train as he launched his bid for re-election to the U.S. Senate. Douglas, however, had not invited Lincoln, yet the challenger dogged him on the line from Chicago to Springfield, catching every speech so as to answer it as soon as possible. This tactic soon obliged Douglas to share the platform with Lincoln—hence the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Midway between Bloomington and Springfield, the train stopped for dinner in the town named for Lincoln, and there Volk met the candidate, who shook his hand “with a vice-like grip.” Lincoln recalled that he had read in the papers about Volk’s statue of Douglas, at which point the sculptor secured a promise from Lincoln to sit for a bust of himself at the first opportunity.[7]

Making the Mask and the Bust

That opportunity came in 1860, when Lincoln was in Chicago as an attorney in the “sandbar case,” Johnston v. Jones and Marsh, which involved a dispute over the ownership of accretions of land at the mouth of the Chicago River. Going to the U.S. District Court, Volk found Lincoln, who remembered his promise to sit to Volk, and it appears that he did so on four days, March 29 through April 1. Three of those sittings took place before the court reconvened at ten a.m.; the fourth, which lasted “more than four hours,” was on a Sunday. Volk later recalled that Lincoln was always prompt and often ascended to his fifth-floor studio “two, if not three, steps at a stride.”[8]

Volk’s first task when Lincoln sat to him was to sculpt a clay model for his bust. To do this, he took “measurements of his head and shoulders,” and made a cast of his face. Not only would such a cast “save him a number of sittings,” it also was necessary before Volk could sculpt Lincoln in plaster and marble.[9]

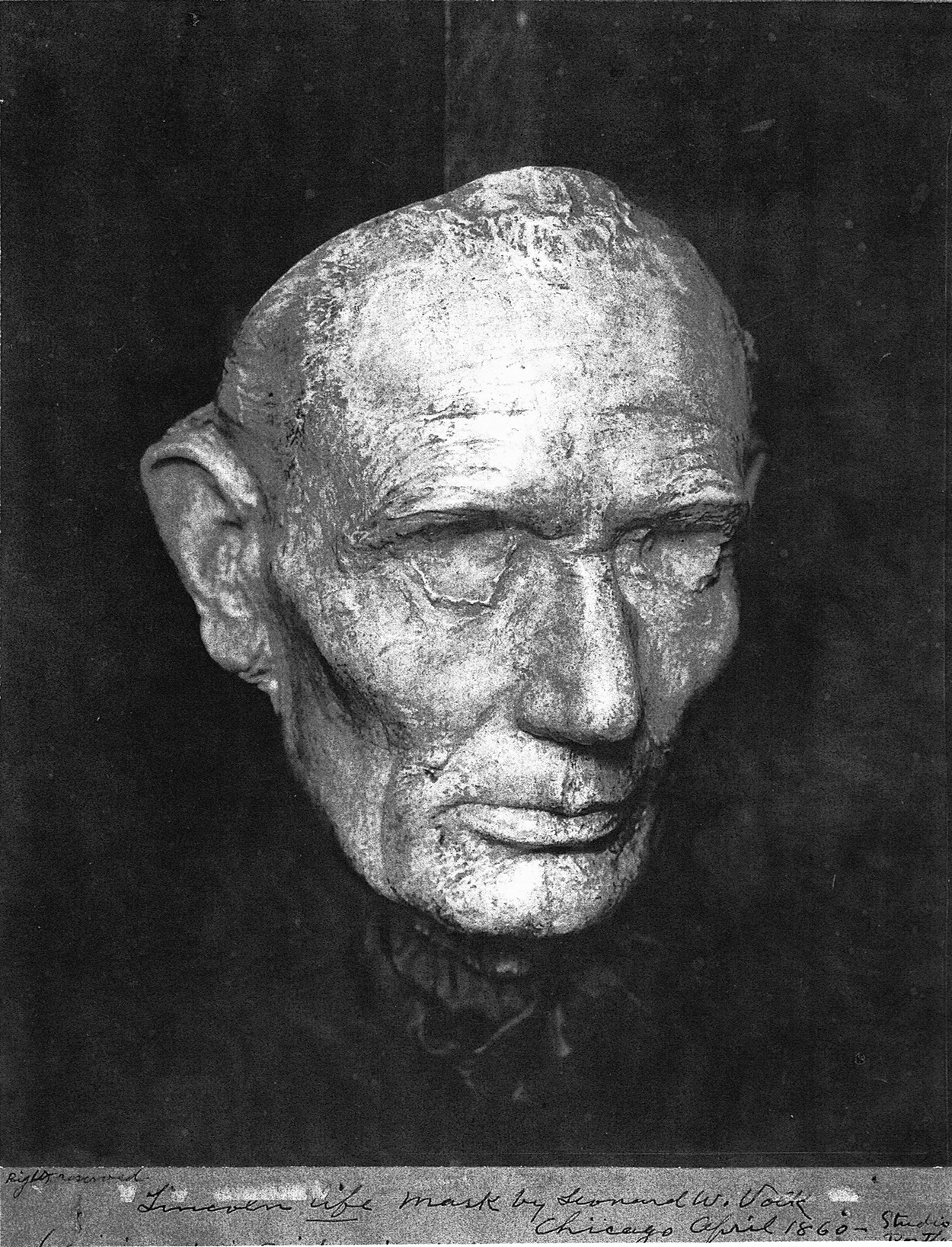

Volk described in detail how his life mask of Lincoln was made [Figure 2]:

He sat naturally in the chair when I made the cast, and saw every move I made in a mirror opposite, as I put the plaster on without interference with his eyesight or his free breathing through his nostrils. It was about an hour before the mold was ready to be removed, and being all in one piece, with both ears perfectly taken, it clung pretty hard, as the cheek-bones were higher than the jaws at the lobe of the ear. He bent his head low and took hold of the mold, and gradually worked it off without breaking or injury; it hurt a little, as a few hairs of the tender temples pulled out with the plaster and made his eyes water.[10]

Figure 2. Volk cast the life mask and hands of Lincoln in 1860. Later, Douglas Volk, the sculptor’s son, planned a subscription whereby those originals were acquired for the National Museum (the Smithsonian Institution) in 1888. Several years before that undertaking, the elder Volk arranged for the casting of three replicas of the original mask; a photograph of one is shown here. (Courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.)

Figure 2. Volk cast the life mask and hands of Lincoln in 1860. Later, Douglas Volk, the sculptor’s son, planned a subscription whereby those originals were acquired for the National Museum (the Smithsonian Institution) in 1888. Several years before that undertaking, the elder Volk arranged for the casting of three replicas of the original mask; a photograph of one is shown here. (Courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.)Volk’s son described in more detail the process of making a life mask:

The sitter, or, as one might more fittingly say, the patient, being duly resigned to his fate, has his face anointed very lightly with oil. The hair about the temples and forehead is then carefully matted down either with clay or lard—sometimes the parts being covered with oiled silk. The plaster of Paris is then mixed with water in a bowl until it becomes the consistency of thick cream. The patient being covered with a sheet to keep the casting confined to his head, the plaster is poured on his face by means of a spoon until it is completely covered with the exception of the nostrils and eyes. The plaster soon hardens, incidentally becoming quite hot, when the sitter enjoys about half an hour of discomfort and apprehension! Once the plaster is thoroughly hardened it is gently freed from the face and an accurate mould is obtained. This is allowed to become perfectly dry and liquid plaster of Paris is poured into it, and when this in turn becomes hard enough the outer mould is chipped off, being destroyed; it is called the ‘waste mould.’ But now the cast, a perfect reproduction of the face, is revealed.[11]

For Volk, the cast or mask that he made of Lincoln’s face was but one step toward sculpting his entire head. After Lincoln’s sittings, Volk completed the mask just as other sculptors would do; he cast the model in plaster, making a mold from which multiple copies could be made. In the first instance, however, it is the mask itself that was supremely valuable. The mask is sometimes mistakenly thought to be a death mask because it lacks eyes, eyebrows, and a full head of well-brushed hair, but it documents Lincoln much more exactly than the only other cast of his face, taken by Clark Mills early in 1865, after a beard had substantially changed his appearance. Simply put, Volk’s mask of the candidate in 1860 is the first and most basic depiction of Lincoln. All subsequent representations, whether by Volk or anyone else, are secondary and derivative.[12]

By itself, Volk’s mask of Lincoln is difficult to display. To make it lie flat on a table or to mount it upright, and to look more complete, Volk extended the back of the head, placed a tuft of hair on the top, and added the Adam’s apple. Over the years, others have done more: to display the mask at an angle they have supported it in different ways, and to hang it upright they have used cross-bracing, hooks, or wires.

With each sitting, Volk worked on the clay model of Lincoln’s head and torso. On the last day, as Volk recalled, he took measurements of Lincoln’s “breast and brawny shoulders as nature presented them.” To do this, Lincoln “stripped off his coat, waistcoat, shirt, cravat, and collar.” After standing for Volk “without a murmur for an hour or so,” Lincoln “hurriedly” left for another engagement. But, as Volk wrote, he soon returned, having not fully dressed himself. The sleeves of his undershirt were “dangling below the skirts of his broadcloth frock coat” and, as he said, “it wouldn’t do to go through the streets” that way. Volk at once helped him re-dress, and out he went again “with a hearty laugh at the absurdity of the thing.” Volk’s account, however true, may only illustrate Lincoln’s well-known inattention to personal attire.[13]

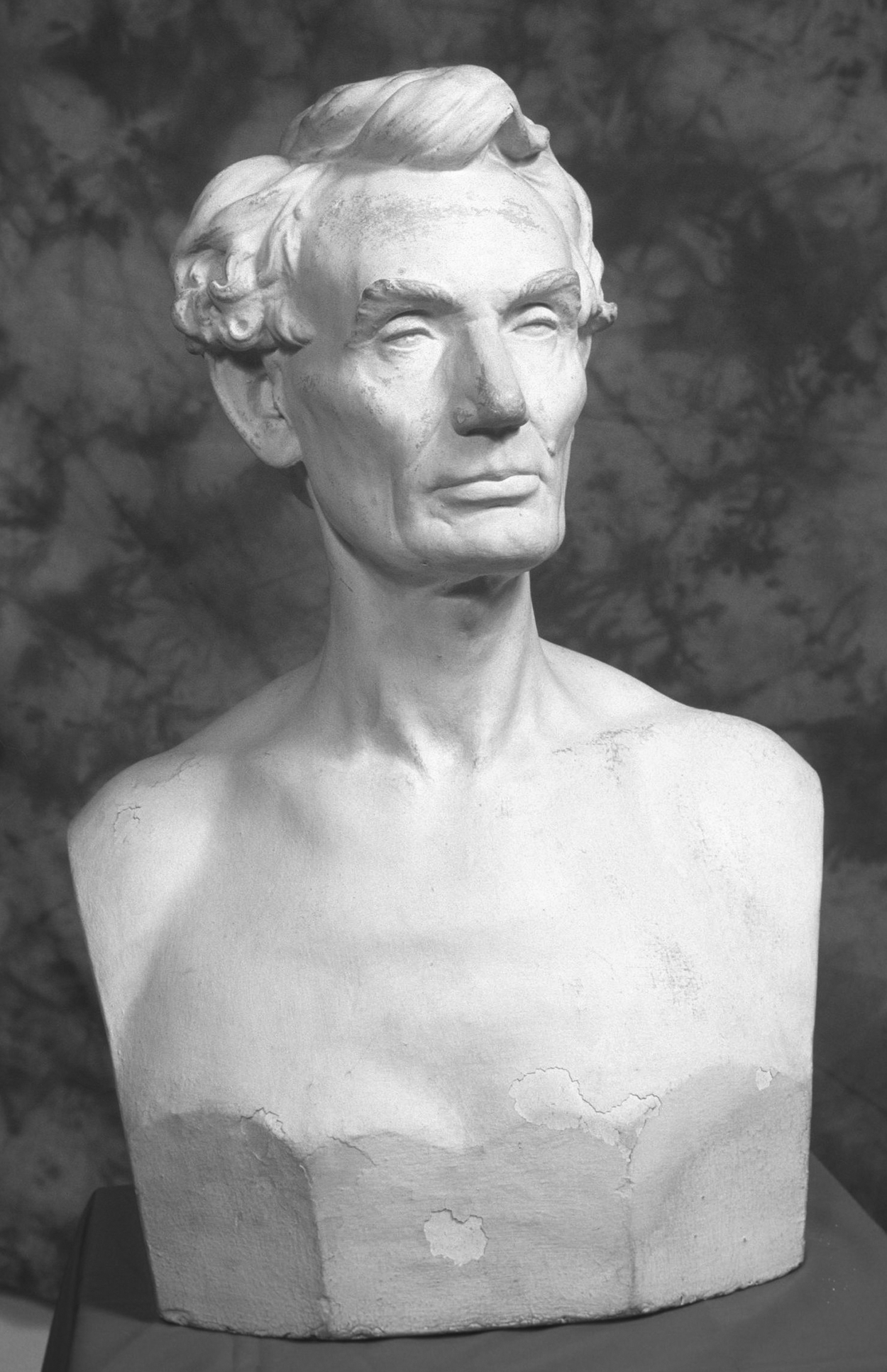

Making the Hermes Bust

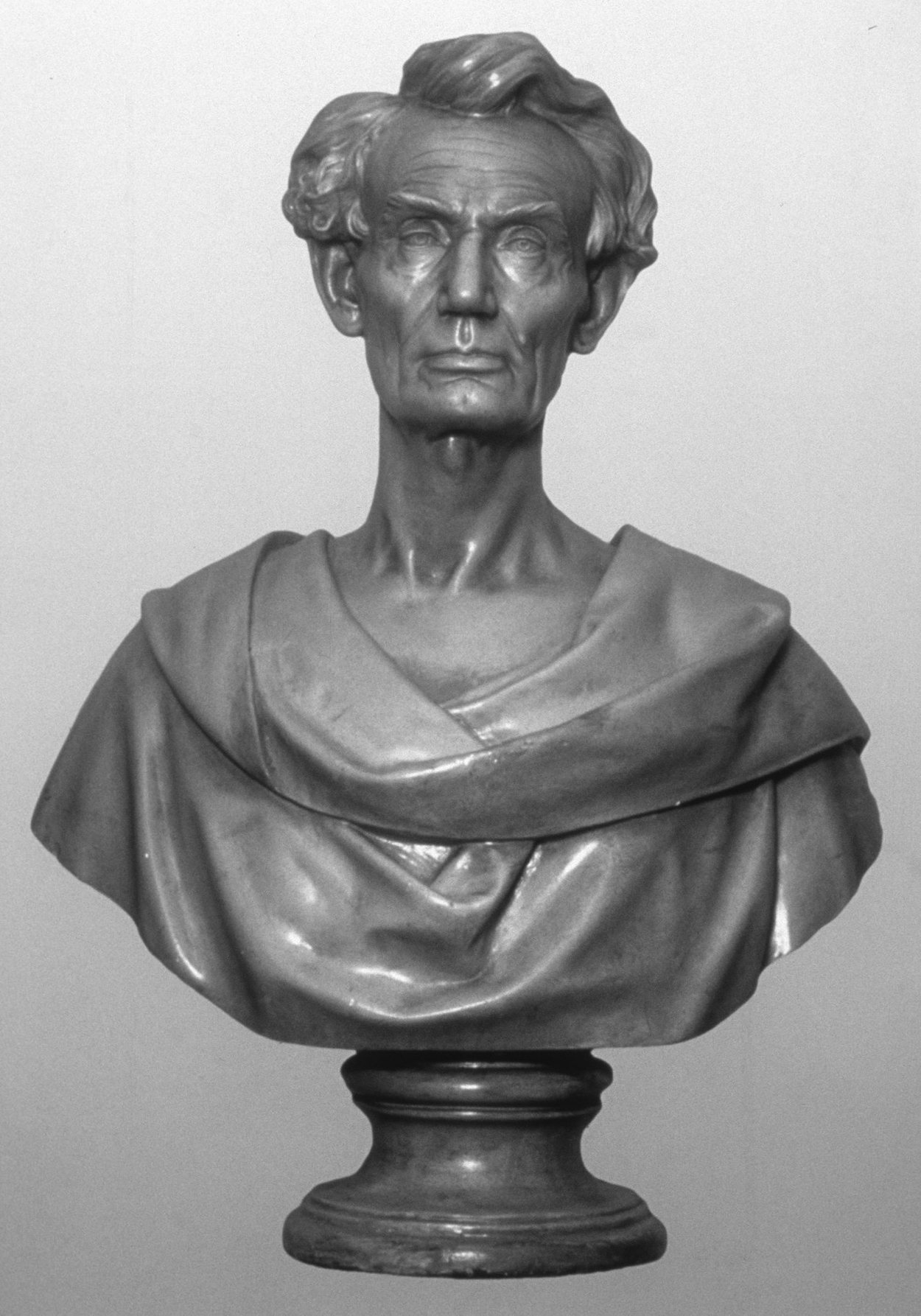

Volk’s purpose in measuring Lincoln’s neck and chest was to sculpt in a neoclassical manner a “Hermes” bust. [Figure 3] This was a standard sculptural form throughout the nineteenth century, although it is rarely used afterwards. Such a bust was typically made without arms. For Volk this meant that the planes of the sides were cut vertically and the edge between them and the front was chamfered. So designed, the work had a certain monumentality. On May 17, 1860, Volk filed with the U.S. Patent Office a design for a Hermes bust, “viz., head, shoulders and breast cut off below the pectoral muscles and without drapery or covering of any kind.” Volk’s application, formally witnessed by friends and accompanied by a photograph, would legally secure his rights in “a new and original design” that, when filed in the Patent Office, could be protected from reproduction. The application was allowed on June 12, 1860, and thereinafter Volk was careful to place his name and that date on the shoulder of his copies of the bust.[14]

Figure 3. The Hermes bust. After Volk cast Lincoln’s face at the end of March 1860, he modeled the entire head and upper body, thus making a “Hermes” bust. (Courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.)

Figure 3. The Hermes bust. After Volk cast Lincoln’s face at the end of March 1860, he modeled the entire head and upper body, thus making a “Hermes” bust. (Courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.)Volk also used a popular neoclassical form by clothing his Lincoln bust in a Roman toga. Nineteenth-century American sculptors often chose to outfit their subjects in classical garb. In making draped busts of Lincoln, Volk like other sculptors freely varied the folds of the garment and the widths of the shoulders.

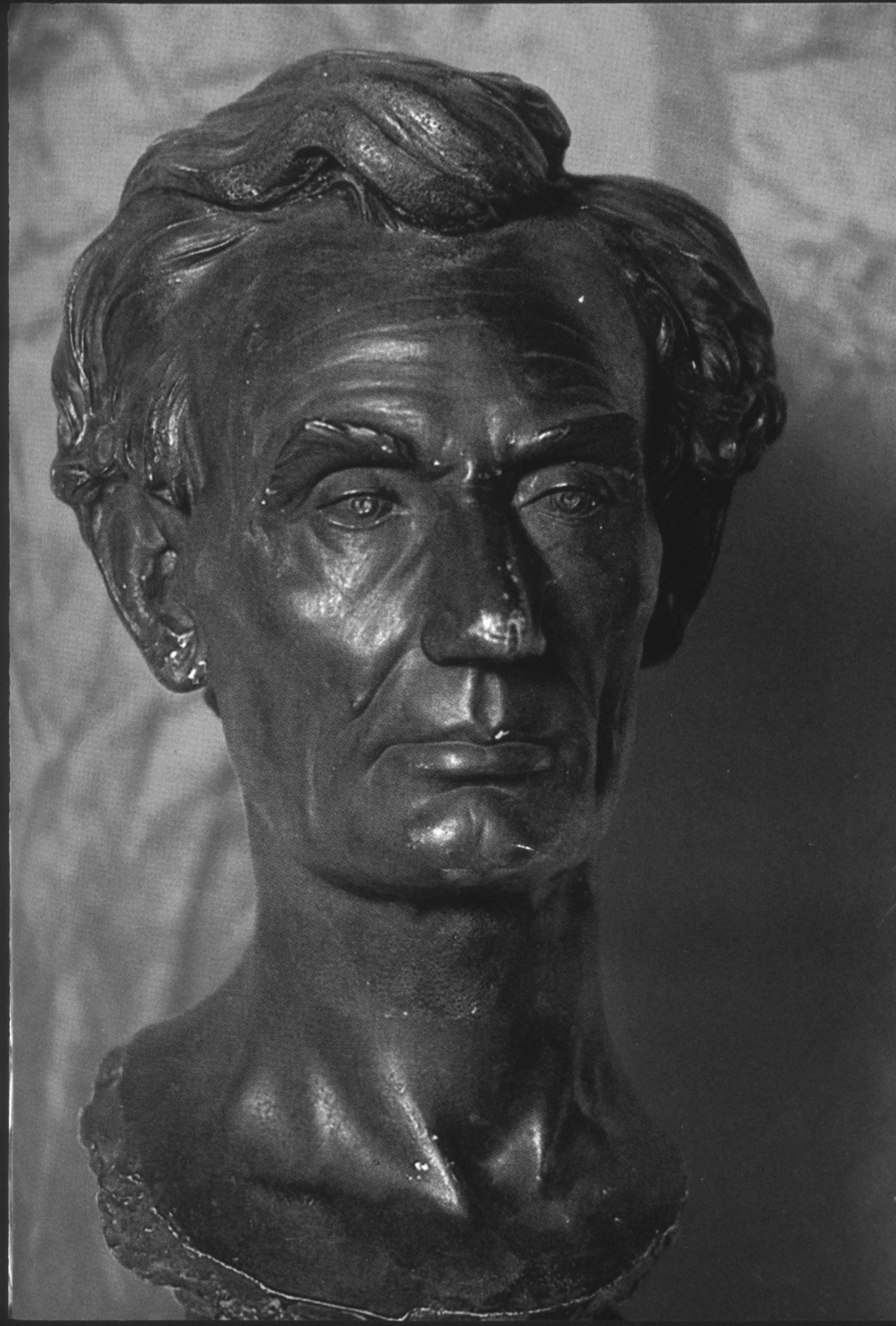

Making the Short Bust, a Cameo, and the Cabinet Bust

In addition to a Hermes bust, Volk fashioned what is commonly known as his “short bust” of Lincoln. [Figure 4] He made such a bust simply by duplicating the head of the Hermes and a portion of the body that he cut from the Hermes bust in an irregular way. There was a calculated spontaneity in trimming the Hermes in this way, and it also made possible a considerable savings in how much sculptural material was required. Mounted on a base, the short bust became in time the most popular version of Volk’s Lincoln sculptures.

Figure 4. The short bust. To make this bust, Volk duplicated the head of the Hermes bust but cut away most of the upper body. He thus created what became the most popular of his many Lincoln sculptures. (Courtesy of Antiques magazine.)

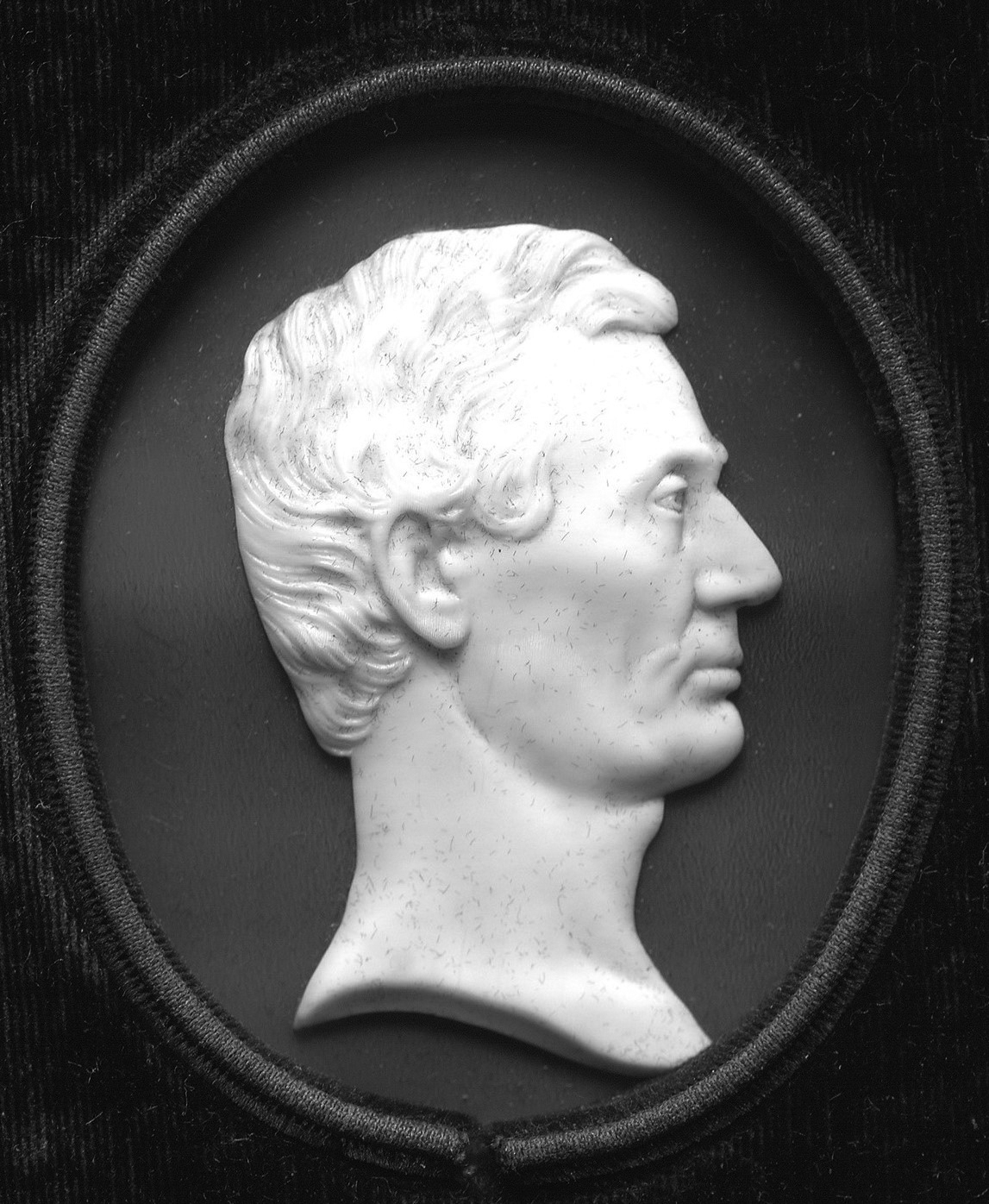

Figure 4. The short bust. To make this bust, Volk duplicated the head of the Hermes bust but cut away most of the upper body. He thus created what became the most popular of his many Lincoln sculptures. (Courtesy of Antiques magazine.)Later in 1860, Volk also made a cameo of Lincoln in ivory. [Figure 5] Since he first became a sculptor, Volk had advertised himself as a “sculptor of portrait statuary in clay, marble, and cameo brooches, bracelets &c.,” and it was one of these miniatures that was presented to the Huntington Library in 1953 by descendants of Charles H. Ray, co-owner of the Chicago Tribune which had strongly supported Lincoln’s nomination. The Huntington’s cameo, which shows Lincoln’s head in profile, is a small, delicate work, white on brown. Like other sculptors of the period, Volk made such cameos, especially early in his career, as a way of providing inexpensive images. After sculpting much larger works in the round, Volk may have cut the Huntington cameo simply as a favor for Dr. Ray.[15]

Figure 5. A cameo of Lincoln. Volk presented this miniature profile in ivory, about 2 inches high, to Charles H. Ray, co-owner of the Chicago Tribune and a warm supporter. (Abraham Lincoln Miniature Relief Portrait, 1860, by Leonard Wells Volk; courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif.)

Figure 5. A cameo of Lincoln. Volk presented this miniature profile in ivory, about 2 inches high, to Charles H. Ray, co-owner of the Chicago Tribune and a warm supporter. (Abraham Lincoln Miniature Relief Portrait, 1860, by Leonard Wells Volk; courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif.)When a reporter visited Volk’s studio a month after the sandbar case, he found that Volk was not only completing his short bust of Lincoln but making a smaller cabinet-size version. “Both are speaking likenesses, marvelously natural. Everyone who has seen them, at once pronounces them to be ‘Old Abe’ himself, and so indeed they are, and in the highest artistic sense worthy of the subject.” Volk “has never achieved a happier success,” the reporter opined. “His Douglas is excellent, and has widely won encomiums.” So have his busts of several other well-known citizens, “but among them all, none is a better triumph than that of Lincoln, copies of which will be widely called for upon its publication under a patent now being secured by Mr. Volk.” Clearly, Volk was preparing to market the Lincoln likeness that he had captured.[16]

Casting Lincoln’s Hands

On May 17, 1860, “in case of Mr. Lincoln’s nomination” at the “Wigwam,” the temporary structure for the Republican convention in Chicago, Volk had the proprietor of a nearby store place his plaster bust of the candidate in his window so the delegates “could see what sort of a looking man” they were about to choose. Volk took the evening train to Springfield, and may have been the first person from Chicago to congratulate the nominee in person the following afternoon, Friday, May 18. Although Volk worried lest his hands be again crushed in Lincoln’s grasp, he did not forget to obtain Lincoln’s cooperation in a more ambitious project, a full-length statue. Hoping for Mary Lincoln’s approval of the plan, Volk gave her a copy of his cabinet-size bust. That miniature sculpture was placed on the whatnot in the front parlor of the Lincoln home, and was included in a woodcut of that room that appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.[17]

After an evening in which the “bells pealed, flags waved, and cannon thundered forth the triumphant nomination of Springfield’s favorite and distinguished citizen,” Lincoln took time to supply Volk with photographs and props for his statue. On Saturday, May 19, before he met the delegation from the convention that would officially notify him of his nomination, Lincoln, “in his best broadcloth suit,” stood before Preston Butler’s camera for front, back, and side photographs. Volk remembered a conversation with Lincoln as they were walking to Butler’s photo studio. “I suppose you will vote for your friend Douglas if he is nominated?” “Certainly,” Volk replied, “but if he is not, I shall go for you.” On May 20, Lincoln let Volk make casts of his hands, gave him the “black alpaca campaign suit of 1858,” now “well-darned and mended,” and “a pair of newly made Lynn No. 10 pegged boots,” covered with “a liberal coating of Springfield mud.” Later, back in Chicago, Volk put Lincoln’s coat and boots on display at Col. Wood’s Museum on Randolph Street between Clark and Dearborn, and they all burned up in the great fire of 1871. Volk also lost at that time the photographic negatives taken by Preston Butler, none of which he had ever developed.[18]

The most lasting outcome of Volk’s visit to Springfield was the cast that he made of each of Lincoln’s hands. [Figure 6] Copies of these casts, particularly copies of Lincoln’s right hand, are ubiquitous because of Volk’s account of how the original was taken. As Lincoln’s right hand had become swollen from shaking so many hands of those who had congratulated him, Volk sought some way to steady it before applying plaster for a cast. Asked by Volk to hold something in his hand, Lincoln looked for a piece of pasteboard, but could find none. When Volk suggested that “a round stick would do as well as anything,” Lincoln “went to the wood-shed,” returned with the “end of a broom-handle,” and began to “whittle off the edges.” To Volk’s remark that such whittling was not necessary, Lincoln replied, “Oh well, I thought I would like to have it nice.”[19]

Figure 6. Planning to make a full-size sculpture of Lincoln, Volk cast his hands. Copies of those casts are ubiquitous, partly because Volk’s account of sculpting Lincoln became so widely known. (Courtesy of Chicago History Museum.)

Figure 6. Planning to make a full-size sculpture of Lincoln, Volk cast his hands. Copies of those casts are ubiquitous, partly because Volk’s account of sculpting Lincoln became so widely known. (Courtesy of Chicago History Museum.)Leonard Volk as well as his son Douglas seem to have had a special fondness for the cast of Lincoln’s right hand. When in Rome in 1869, Volk had it sculpted in marble for his brother Cornelius, who was a stonecutter in Quincy, Illinois. That piece is now in the Taper collection of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. It is possible that Douglas Volk caused J. Alden Weir, an artist friend from their student days in Paris, to draw that hand for the December 1886 issue of Century. If so, Weir’s sketch in effect acknowledged the portrait that Volk had painted of Weir. In any event, the need for Lincoln to grasp a mere broom handle fortuitously raised a utilitarian casting into a work of art.[20]

As Leonard Volk began to cast Lincoln’s other hand, the left one, he paused a few moments to hear Lincoln tell him about the scar on the thumb. “You have heard they call me a rail splitter . . . Well, it is true I did split rails, and one day while sharpening a wedge on a log, the ax glanced and nearly took off the end of my thumb off and there is the scar, you see.”[21]

Marketing Volk’s Lincoln Sculptures

Returning to Chicago after Lincoln’s nomination, Volk met on the train Gov. Edwin D. Morgan of New York and other members of the notification committee, several of whom ordered cabinet busts of Lincoln “like the one on his mantel.” For the next few weeks Volk was occupied in making Lincoln busts, both cabinet and life size. “For fidelity of likeness and artistic execution,” the Chicago Tribune declared, Volk’s Lincoln is “unsurpassed . . . It is worthy of a place in every Republican counting house, office and library in the land.” The bust, according to the Chicago Record, is “an admirable work of art, and a perfect ‘counterfeit presentment’ of ‘Honest Old Abe.’ It receives the universal commendation of his ‘troops of friends,’ who ‘from morn till dewy eve,’ flock to Volk’s studio to see it.” Writing to Lincoln on June 5, 1860, Volk enclosed a photograph of the full-size bust, “orders for which are becoming quite numerous,” and he added that he would shortly go to New York “for the object of publishing the busts there for that section of the country.” “We presume,” wrote the New York Evening Post, “that Republican clubs and admirers of the ‘Coming Man’ will eagerly seek for copies of this reliable likeness.” Lincoln in Republican clubs and counting houses across the North—there was at least a touch of partisanship in the way that Volk marketed Lincoln, just as he had done with Douglas.[22]

Volk carefully balanced the political scales in the clippings that he collected for a handbill to advertise his Lincoln and Douglas works. In that flyer, he sold the Douglas statuette to agents retail at $4, the Lincoln life size bust at $3, and the Lincoln cabinet bust at $1, items which they in turn were to price at $8, $6, and $2.50. The prices varied in the newspapers. A Peoria paper, for instance, advertised “Volke’s Statuette” of Douglas for $7 and the Lincoln busts for $5 and $2.[23]

To increase the sale of his Lincoln busts, Volk had a New York printer prepare a form for “drummers” (salesmen). He filled out one such form for his brother, Abram Volk, authorizing him “to act as Genl. Agent in Pittsfield, Mass. & Vicinity.” Back home, Volk’s wife wrote Abram’s wife urging her to visit: “Do come on, I will set you [to] cleaning heads.” Already, as Emily Volk noted, “I have to hire a good deal of that done now, scraping Lincoln Busts.” (To prepare plaster of Paris busts for sale, they had to be cleaned and scraped, and then sealed.)[24]

Volk’s distribution of his Lincoln busts in 1860, and beyond, was more successful than any other enterprise that he ever undertook. On one occasion, Lincoln himself recognized Volk’s work. When a Connecticut Republican wrote him for a likeness, the candidate recommended not a photograph, but “one of the ‘heads’ ‘busts’ or whatever you call it, by Volk.”[25]

Volk’s Lincoln sold so well during the first Lincoln campaign that he thought he deserved a consulate after the election. He returned to Springfield in January 1861, hoping that Lincoln would appoint him to Livorno, the seaport city on the Tuscan coast, a short distance from the quarries of Carrara. Volk’s artistic career would be further advanced by such an appointment, and Lincoln made several such appointments of artists and writers, as did other presidents of the day. Volk believed that Lincoln had “promised” him a consulate and wrote him a reminder. When nothing came of it, however, Volk could not really complain—Lincoln has given him a good start on a whole family of likenesses.[26]

One measure of Volk’s success was his intervention to stop others from copying his work. The Chicago Tribune told the story in a diverting way, and it was widely reprinted:

A few days since our well esteemed young townsman and artist, Leo. W. Volk, Esq. . . . was confronted by an un-distinguished exile and fellow countryman of Garibaldi, who bore upon his shoulder and offered for sale a bust of the President of the United States. A single glance told Volk that the bit of sculpture was a melancholy travesty of one of his own bantlings. There was the same face, head and neck whose faithful outline has made Volk’s ‘Lincoln’ a national and historical piece . . . [placed] on the shoulders and chest of—Henry Clay, a bit of dishonest journey-work . . . [done] to avoid infringement on Mr. Volk’s well-earned patent . . . The artist inquired of the vendor, with an air of interest, where these busts were made . . . Down went Volk into a little basement shop on South Clark street, and there, sure enough, two more illustrious importations from the land of the olive and the vine [were] hard at work President-making. Quoth Volk, ‘Are you aware you are using my property without my leave?’ . . . After a parley, the operators in plaster of Paris succumbed, and promised to desist and break their molds. ‘Let me see you do it right off,’ said Volk, in Romanese. ‘Wait for a day or two,’ rejoined, in Italian, the emigrants from the temporal domain of the Pope. Expecting them to decamp after he left, Volk ‘took up a huge mallet. When you break this mould and these busts I advise you do to it so (whack), and so (whack), and so (whack), and so (whack).’ The plaster flew, the mold was a shapeless mass, the row of busts were sadly short of noses, chins, heads; sublime ruin reigned when Volk laid down the mallet. The gentlemen from the region of the Tiber pulled foot for a magistrate, and represented their grievances as viewed from their standpoint . . . a hearing was had before a jury, who found a verdict against Volk for six and a quarter cents, that being deemed probably a fair award for the use of the mallet . . . Mr. Volk has before this been the victim of the dishonesty of this class of people in stealing his works.

Such, with hints of the nativism of Volk’s day, was one way of upholding his patent.[27]

Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 led to an increased demand for copies of Volk’s works, especially the full and cabinet size busts, and again the sculptor was vexed by piracies. On a trip to New York to collect art for the Northwestern Sanitary Fair in Chicago, Volk was “much gratified to observe at nearly every turn . . . my busts of our late revered President” which were “so frequently displayed in the windows and on the building fronts.” But Volk felt aggrieved that “from all the busts and hands of the President sold in this city not a farthing has been paid to me for the time, labor, and money they have cost me.” It was enough to “institute legal proceedings against those parties who have so unceremoniously appropriated my work.”[28] [Figure 7]

Figure 7. The draped bust. It was conventional in Volk’s day for sculptors to clothe busts of contemporary subjects in classical garb. (Courtesy of Chicago History Museum.)

Figure 7. The draped bust. It was conventional in Volk’s day for sculptors to clothe busts of contemporary subjects in classical garb. (Courtesy of Chicago History Museum.)Volk’s Prominence in Chicago

The Civil War called forth sculptors to create commemorative monuments, and Volk helped to meet the demand. He had in effect already entered the field in Chicago by sculpting a monument in Rosehill Cemetery in memory of the fifteen firemen who in 1857 had lost their lives in a conflagration on Lake Street, the city’s main commercial artery at that time. Soon after the Civil War, that monument was placed on an axis with Volk’s “Our Heroes,” Cook County’s commemoration of its fallen dead. Nearby, Volk created monuments for three other Chicago units, and he also memorialized the Civil War elsewhere, most prominently in Girard, Pennsylvania, and in Rock Island, Illinois.

Volk was a leader in art activities in Chicago in the Civil War era. He organized the first Chicago Exhibition of the Fine Arts in 1859. He participated in forming the Chicago Art Union in 1860, in the lottery of which twenty winners were offered either his life-size bust of Lincoln or his statuette of Douglas. He was in charge of the Art Department of the Sanitary Commission fairs in Chicago which included “some three hundred paintings and some statuary” in 1863, and “over five hundred works” in 1865, in each of which Volk’s own works were exhibited. In 1867, Volk was the leading founder of the Chicago Academy of Design (precursor of the Art Institute of Chicago), and served as its president for many years. The Academy offered art classes and public lectures, and served as a venue for art exhibitions.

His prominence in art matters in Chicago caused him to be written up in Biographical Sketches of the Leading Men of Chicago, which was published in 1868. In John Carbutt’s photographs for this volume, Volk is either standing beside his Hermes bust of Lincoln or sitting next to it, chisel in hand. In the background is his bust of Douglas; on the wall are his sketches for the Douglas Tomb and the Firefighters’ Monument; and, lying on the floor, is his cast of Lincoln’s right hand. The Lincoln was first exhibited in 1866 at the art gallery of the Crosby Opera House, at which time, according to Volk, Mary Lincoln came to see it, “threw her arms around the neck and declared it the most perfect portrait of her husband ever made.” The bust was then shipped to Paris where it was shown in the Universal Exposition of 1867. Returned to Chicago, the bust was “purchased by subscription by a few gentlemen,” including Isaac N. Arnold. It was then presented to the Chicago Historical Society where, in 1871, it was destroyed, “together with the original draft of the Emancipation Proclamation fastened in the wall just above it.”[29]

In October 1868, Volk felt the need to leave Chicago, to obtain “fine Italian marble” directly from Carrara and to find more skilled and less expensive workmen than in Chicago. In Rome, he met Charlotte Cushman (1816–1876), the noted American tragedienne who had an interest in palmistry. Learning that he had cast Lincoln’s hands, she begged to see them. Volk accordingly brought them to a gathering at her residence where he handed her the left hand, which she clutched as a “precious gem.” Pointing to the palm she cried to a friend in her melodramatic manner, “There, what did I tell you? The line of life is cut suddenly off!” And then that “big wrinkled rail-splitting hand was passed among the distinguished company.” Together with the right hand that held part of a broom handle, the two were “closely scrutinized, furnishing the chief topic of discussion during the evening.”[30]

During this sojourn in Rome, Volk not only completed several commissions for statuary work, but collected a number of antique casts for the Chicago Academy of Design, before returning home in May 1869. In December 1870, he crossed the ocean yet again, this time with his wife and their family, including Douglas, age 14, and Honora, age 9. For several weeks, they were tourists in Malta, Syracuse, Naples, and Rome itself. During their sightseeing, Volk’s models for new sculpture reached his studio, and soon his workmen there were “making the chips fly from the white marble blocks.”[31]

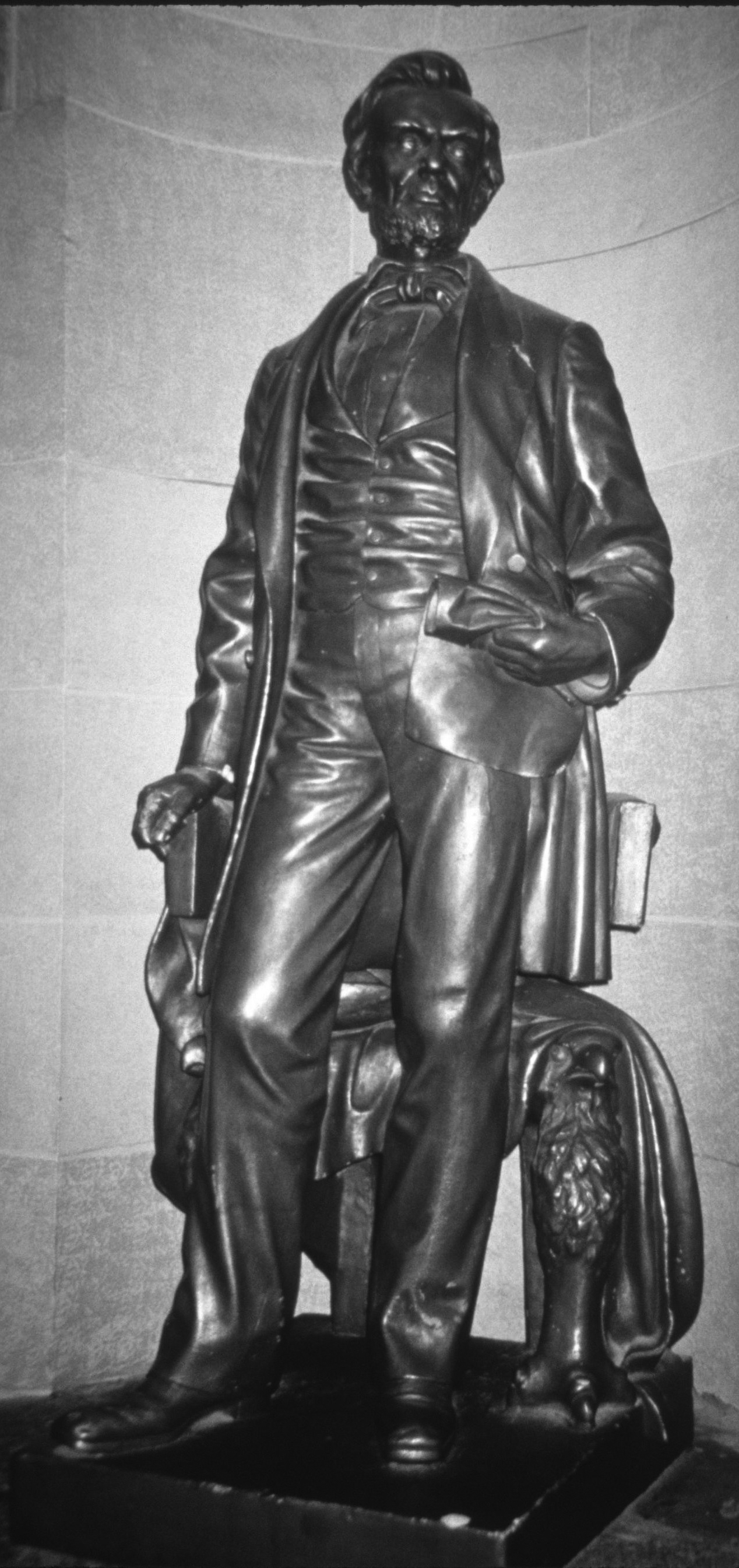

In July 1872, after the great Chicago Fire, the Volks returned home, except for Douglas Volk who wished to study painting in studios in Rome and Paris. In burnt-over Chicago, Leonard Volk relocated his work to McVicker’s new theater and carried on with his sculpture, accepting commissions for several dozen portrait busts. He also increased his Lincoln and Douglas oeuvre. He exhibited plaster statuettes of both of them at the Inter-State Industrial Exposition of 1873, at which Chicago celebrated its Phoenix-like recovery from the Fire. He showed a bearded full-length Lincoln as the Emancipator in different ways, holding the Proclamation with one or two hands or with one hand and the other on a pedestal.

With further work, Volk developed full-size statues of both Lincoln and Douglas for installation in the new capitol of the State of Illinois. These plaster works, painted to simulate bronze, show Douglas in debate and Lincoln just rising in a Cabinet meeting at which he presented the Emancipation Proclamation. [Figure 8] Volk delivered the two statues early in 1877, but the bill to compensate him for them and to authorize “replicas of them in marble or bronze,” failed to pass the legislature, apparently because appropriations to complete the Lincoln and Douglas tombs were more pressing. Nearly a decade later, Volk noted the situation and the state’s unpaid debt to him in a “Memorandum for the benefit” of his wife, “in case of sudden death to me.” Not only had Volk “spent ten months in producing the models” of his Lincoln and Douglas statues in the State House, but the legislature had failed to support his plan to have them sent to Carrara, Italy, to be “made in finished statuary marble.” Both statues are “a trifle larger than life-size, a resort of the sculptor to impart dignity and impressiveness” to them. At first they sat on wooden boxes close to the walls of the original entrance to the Capitol, then they were pulled into the center of the corridor and made to face each other, and finally, in 1894, they were placed in niches of the Rotunda.[32]

Figure 8. After making statuettes of Lincoln that showed him with a beard and with the Emancipation Proclamation in hand, Volk cast a full-size standing version for the new (1876) Illinois State Capitol. (Courtesy of Mark Sorensen.)

Figure 8. After making statuettes of Lincoln that showed him with a beard and with the Emancipation Proclamation in hand, Volk cast a full-size standing version for the new (1876) Illinois State Capitol. (Courtesy of Mark Sorensen.)Ever since 1860, Volk had hoped to secure a commission for a full-size monument of Lincoln, but not until 1881, when his article on making the life mask was published in Century, did his objective come into view. Learning that a committee in Rochester, New York, wished to erect a Civil War monument, Volk proposed a design in which a soldier and a sailor flanked a column crowned by an eagle. By happy coincidence, H. S. Greenleaf, soon to be a member of Congress and chair of the committee, read Volk’s article, praised its “many descriptions of the great man,” and urged his committee to commission Volk for Rochester’s monument. By the time that sufficient funds for the monument had been raised, Volk had revised his design, placing a ten-foot bronze Lincoln, not a resting eagle, at the top. And with that design the monument was dedicated in 1892.[33]

Throughout his career, Leonard Volk’s kinship with Stephen A. Douglas worked to his advantage. Before the Civil War, Douglas acquired land just south of Chicago’s city limits, on the shore of Lake Michigan, and built a cottage on what became the 35th Street edge of the property. Volk and his family lived there after Douglas’s death in 1861, and Volk designed the Douglas tomb nearby which was finally completed in 1881. Although successful in memorializing Douglas, Volk’s efforts to secure the major Lincoln commissions in Illinois fell short, much to his disappointment. In 1868, the National Lincoln Monument Association chose Larkin G. Mead’s design for the Lincoln Tomb in Springfield, after rejecting the designs of Volk and several others. Also contested was Eli Bates’s $40,000 bequest for a Lincoln statue in Chicago. In 1881, “so far as can be ascertained, two candidates have the lead,” Leonard Volk and Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1847–1907), who at the time was emerging as America’s preeminent sculptor. “There is a great deal of quiet effort being put forth in behalf of these two sculptors,” the New York Times reported, but by 1884 Saint-Gaudens won the prize. Robert Todd Lincoln, who distinguished himself in governmental service and who was a perceptive critic of artistic representations of his father, took a keen interest in these developments. He regarded Larkin Mead’s statue as “a very excellent one,” and he supported the selection of Saint-Gardens. When asked about Volk as a sculptor, Lincoln candidly expressed his opinion to a member of the selection committee: “Mr. L. W. Volk, of Chicago, as you know, was formerly a tombstonecutter. He made a bust of my father before he grew his beard, which has always seemed to me a most excellent likeness of him. By dint of constant work upon that bust, and upon one of Mr. Douglas, he has succeeded in making very good likenesses, but I must say that I think Mr. Volk possesses no artistic sense whatever.”[34]

Volk’s Bankruptcy

Although adept at securing commissions, and alert to the value of his connection to Lincoln, Volk let his own debts outpace his income. In fact, he was so haphazard in keeping “proper books of account” that his creditors filed a bankruptcy suit against him. Their detailed 103-page petition (some pages of which are duplicates) provides a remarkable window into the sculptor’s finances. The largest of the secured debts was $8,500, held by Edmund C. Rogers, a Chicago physician and the brother of Randolph Rogers, one of Volk’s closest friends who had sat to him for a bust when both were studying sculpture in Rome. The largest of the unsecured debts, $8,000, was due the estate of Timothy S. Fitch, a collateral relation of Volk. Emily Keep Schley claimed $1,500, after Volk had completed the Keep family mausoleum in Watertown, New York, which contained his statues of her and her parents, formerly Chicagoans. Volk also had borrowed $600 from Martin Ryerson, a Chicago art collector for whom Volk had sculpted a draped neo-classical bust. Then too Dr. Jonathan K. Barlow of Quincy, Volk’s father-in-law, had loaned him $300. Volk was also indebted to many other individuals for lesser sums, and to two suppliers, $68.68 to the Rutland Marble Company of Rutland, Vermont, and $54.58 to the Gowan Marble Company of Chicago.

Volk’s own assets included the estimated value of his homestead, $1,800; a carefully itemized list of his household furniture valued at $1,200; two leased lots in Chicago with a shed worth $40 on one of them; 40 acres of land in Gainesville, Florida, valued at $1,000; and certain payments due from the State of Illinois for statues of Lincoln and Douglas in the capitol.

Burdened by liabilities so much greater than his assets, Volk found his financial plight summarized in a column regarding “the frantic panic of spendthrifts and bankrupts” that was published in 1878, a day before a sweeping reform of the bankruptcy law went into effect. Yet Volk was not immune from the depression years following the Panic of 1873, in which the wealthier part of the community curtailed their patronage of the arts.[35]

The Chicago Academy of Design found it particularly difficult to stay afloat during that depression, so much so that its supporters in the business community challenged the artists who by charter governed the organization. By the end of the conflict between the “academicians,” the artists themselves, and their business-minded patrons, the Chicago Academy of Design ceased to exist, and the Art Institute of Chicago was formed. Volk was so embittered by this change, which ended his presidency of the Academy, that years later he was unable to write clearly and calmly about the matter.[36]

But he was too self-assured and committed to his career as a sculptor to be defeated by his bankruptcy—nor did he hesitate to sue others for whom he did work but was not paid.[37] Indeed, he received more commissions after his bankruptcy than before. Moreover, by working with his son, Leonard Volk expanded the promotion of his Lincoln sculptures, as will be seen in the continuation of this account in the next issue of this journal.

Over the years, many others have stimulated my interest in the topic of this paper. They include Mark L. Johnson of the Historic Sites Division of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, and Thomas F. Schwartz and James M. Cornelius, both of whom served as the Lincoln curator of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library.

Wayne C. Temple, “Lincoln as seen by T. D. Jones,” Illinois Libraries, 58:6 (June 1976), 452; Leonard W. Volk, “The Lincoln Life-Mask and How It Was Made,” Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine 23:2 (Dec. 1881), 225–26, 228 (hereinafter “Lincoln Life-Mask”).

Volk’s own memoirs provide the most information about his life. Hastily composed in the mid-1880s, his manuscript is penciled on the pages of twelve tablets, each about 6” x 9”. Whenever Volk reached the last page of a tablet, even if in mid-sentence, he began a new tablet. He gave a volume number to the tablets, and briefly noted the contents on the first page of some of them. The manuscript is now about evenly divided between the Alfred Whital Stern collection of Lincolniana in the Library of Congress and the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution, and is hereinafter cited as “Volk memoirs.” The Smithsonian’s part is digitized online in its collection of Douglas Volk and Leonard Wells Volk papers, Series 2.

Volk memoirs, 3:83–84, 4:14–16, 4:28–29. The memoirs are not paged but usually the pages are in good order and can be numbered. However, the pagination of Volume 6, Volk’s fullest account of his contacts with Lincoln, cannot be exactly ascertained. Leonard Volk inserted brief passages into the manuscript, Douglas Volk “temporarily removed” and apparently lost certain pages, and Jessie Volk, his daughter-in-law, in typing up portions of the document, further compromised its order. Insofar as possible, Volk’s memoirs have been editorially paginated throughout these notes.

Volk memoirs, 4:60–78; Chicago Exhibition of the Fine Arts, Catalogue of the First Exhibition of Statuary, Paintings, Etc. (Chicago: Chicago Daily Times, 1859); Chicago Art Union, Sculpture Cat. No. 1 (Chicago: Chicago Press and Tribune, 1860). See also Volk’s letters from Europe in The Rock Islander (Rock Island, Ill.), Dec. 12, 19, 1855; June 4, 11, 1856.

Volk memoirs, 6:7–8; Leonard Wells Volk Papers, Special Collections, Syracuse University Libraries, Syracuse, N.Y.; microfilm in Archives of America Art, Smithsonian Institution, roll #4280 (hereinafter Volk Papers, Syracuse University).

Volk was imprecise in dating Lincoln’s visits to his studio when he wrote about the matter twenty years later. This has caused many readers of Volk’s account to think that Lincoln gave him more time than his other commitments would have made possible. The court had taken up the sandbar case on March 23, 1860. Volk noted that Lincoln’s first sitting was on a Thursday. That would have been March 29, the day on which it was reported that Volk is “now at work on a bust of the Hon. Abraham Lincoln.” The court record indicates that the case continued on March 30 through April 3 (except for Sunday, April 1), and that a verdict for Lincoln’s clients was delivered on April 4, after which Lincoln returned to Springfield. After court on April 2, Lincoln delivered a speech in Waukegan, and on April 3, he visited an old friend, Julius White, in Evanston, where he was serenaded in the evening. According to Volk, Lincoln wanted to postpone his trip to Evanston. “I’d rather come and sit to you for the bust than to go there and meet a lot of college professors and others.” Lincoln even sent Volk to see White, the harbormaster in Chicago, to make other arrangements. But White held Lincoln to his engagement. Because of Lincoln’s plans to go to Waukegan and Evanston, and because the sandbar case was about over, Volk was probably obliged to complete his modeling of Lincoln in one long sitting on Sunday, April 1. “Lincoln Life-Mask,” 225–26; Earl Schenck Miers, ed., Lincoln Day by Day: A Chronology, 1809–1865 (Washington, D.C.: Lincoln Sesquicentennial Commission, 1960), 276–78; Chicago Press and Tribune (Mar. 29, 1860), p. 1, col. 2.

Douglas Volk, “Making the Life Mask of Abraham Lincoln,” Magazine of History with Notes and Queries 21:1 (1922), 21.

Designs, 1860, Report of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1860; Arts and Manufactures, Sen. Exec. Doc. 7, 36th Cong., 2nd Sess. (Washington, D.C.: George W. Bowman, 1861), 1:841, No. 1,250.

Church Record [Chicago] (Oct. 1, 1858), 109; Seymour Korman, “Gives Library Rare Cameo of Lincoln Head,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 13, 1953, p. 1, col. 6; The Huntington Library: Treasures from Ten Centuries (London: Scala Publishers, Ltd., 2004), 47.

“Lincoln’s Life-Mask,” 227; Volk memoirs, 6:57–63; Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper 12 (Mar. 9, 1861), 245.

James M. Cornelius and Carla Knorowski, Under Lincoln’s Hat: 100 Objects that Tell the Story of his Life and Legacy (Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press, 2016), 110–11; Century 11:2 (Dec. 1886), 249; Douglas Volk’s portrait of Weir, in Arlene M. Palmer, “Douglas Volk and the Arts and Crafts of Maine,” Antiques 173 (Apr. 2008), 118.

Ibid., 6:73–74; Chicago Press and Tribune, June 7, 1860, p. 1, col. 1; Chicago Record, quoted in Peoria Daily Transcript, June 22, 1860, p. 4, col. l; Volk to Lincoln, item 41759, Ser. 2, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress (microfilm roll 95); “Volk’s Busts of Lincoln and Statuette of Douglas: Extracts from the Press,” Volk Papers, Syracuse University.

Ibid.; Peoria Daily Transcript, June 23 and 30, 1860, p. 1, col. 7. The Lincoln busts when first advertised in Chicago were $10 and $4, twice as much as in Peoria a few weeks later, supply and demand apparently causing the difference. Chicago Press and Tribune, May 29, 1860, p. 1, col. 5.

Form for agents, completed for Abram Volk, July 13, 1861, Volk Papers, Syracuse University; Emily Volk to Till [Matilda] Volk, July 4, 1860, ibid.

Lincoln to James F. Babcock, Sept. 13, 1860, Roy P. Basler et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953–55), 4:114.

Leonard Volk to Abram Volk, June 13, 1861, Volk Papers, Syracuse University.

“A Lay of Modern Rome,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 1, 1861, p. 4, cols. 1–2.

Volk to New York Herald, May 4, 1865, as reprinted in Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1865, p. 4, col. 3; ibid., May 10, 1865, p. 1, col. 4; ibid.

[Elias Colbert and George F. Upton], Biographical Sketches (Chicago: Wilson & St. Clair, 1868), 340; Opera House Art Association, Sculpture Catalog, no. 9 (June 1866), in James L. Yarnall and William H. Gerdts, The National Museum of American Art’s Index to American Art Exhibition Catalogues From the Beginning through the 1876 Centennial Year (Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1986), vol. 6, no. 95142; Volk to Hennecke & Co., Mar. 6, 1890, in Lincoln Lore, no. 731, Apr. 12, 1943.

The Inter-State Exposition Souvenir (Chicago: Van Arsdale & Massie, 1873), 65; “Lincoln and Douglas; Their Statues Placed in Position in the New State House,” Illinois State Journal, Jan. 8, 1877, p. 1; Volk’s “Memorandum,” Mar. 26, 1886, a photocopy of the original before it was sold by the Cyr Auction Company in 2006; Daily Inter-Ocean (Chicago), July 1, 1876, p. 9, col. 3.

Volk to Greenleaf, August 3, 1881; Greenleaf to Volk, Dec. 22, 1881, and Jan. 4, 1886, Volk Collection, ALPL; The Monumental News, 4:6 (June 1892), 219. See images at Donald Charles Durman, He Belongs to the Ages: The Statues of Abraham Lincoln (Ann Arbor: Edwards Brothers, 1951), 15; and F. Lauriston Bullard, Lincoln in Marble and Bronze (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1952), 152.

Chicago Tribune, Sept. 24, 1861, p. 4, col. 1; “Chicago’s Lincoln Monument,” New York Times, June 21, 1881, p. 1, col. 6; Lincoln to George Payson, June 25, 1881, Robert T. Lincoln letterpress books, 4:466, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. For Volk’s feelings about the selection of Mead and Saint-Gaudens, see “Personal,” Rock Island & Moline Daily Union, Oct. 7, 1868, p. 4, col. 1, and Volk to editor, Chicago Tribune, Oct. 22, 1887, p. 15, col. 1.

Case 4823, Cook County bankruptcy records, filed in the Northern District of Illinois and now stored at the Kansas City branch of the National Archives, 98; “Penultimate Petitioners,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 31, 1878, p. 1, cols. 1, 3.

Volk appears three times in the Plaintiff’s Index of the Circuit Court of Cook County, 1871–1898, on file in the Illinois Regional Archives Depository at Northeastern Illinois University.