How Many “Lincoln Bibles”?

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In a 1940 edition of Lincoln Lore, editor and historian Dr. Louis A. Warren stated that “no book could be more appropriately associated with Abraham Lincoln than the Bible,” and he briefly introduced his readers to nine “Historic Lincoln Bibles” that he thought should be linked with the sixteenth president.[1] Eleven years later, Robert S. Barton, son of the Lincoln biographer Rev. William E. Barton, published a paper titled “How Many Lincoln Bibles?”[2] In it, Barton updated the status of Warren’s nine historic Lincoln Bibles, then added three Bibles he thought should also be associated with the 16th president. This list of a dozen Lincoln Bibles has not been critiqued or updated since that time, 1951. But a few significant discoveries, particularly in the past decade, justify a fresh look at this subject.

In this article I update the status of the twelve previously identified historic Lincoln Bibles, discuss which Bibles Lincoln used while president, and introduce four previously unidentified Bibles that should be added to this list. One of these “new” Bibles may have been used by Lincoln’s mother to teach him how to read when he was a child, and another was probably read by Lincoln when he was president. These sixteen Bibles are shown in the table. The first twelve are presented in the order that Warren and Barton discussed them.

In Lincoln Lore, Warren wrote that the Bible was “the single most influential book that Abraham Lincoln read.”[3] An extensive study of Lincoln’s use of the Bible is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that Lincoln utilized the Scriptures extensively to support his ethical and political statements. Lincoln once told a neighborhood friend that the Bible “is the richest source of pertinent quotations.”[4] Lincoln also informed his son Tad, “Every educated person should know something about the Bible and the Bible stories.”[5] Lincoln told a group of visitors in the White House that the Bible was “the best gift God has given to man.”[6] The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (hereafter referred to as CW) contains more than 120 quotations of or references to Scripture made by Lincoln.[7] In his Second Inaugural Address, which he expected “to wear as well as—perhaps better than—anything I have produced,”[8] Lincoln used 701 words, including four quotations from the Bible.[9] Clearly, he saw great value in knowing and quoting the Bible.

| No. | Bible as named by list contributor | Bible as referred to in this article | List Contributor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mother’s Bible | Thomas Lincoln Bible | Warren |

| 2 | Lucy Speed Bible | Warren | |

| 3 | Mary Todd Lincoln Bible | Mary Lincoln Bible | Warren |

| 4 | First Inaugural Bible | Warren | |

| 5 | Pocket New Testament | Warren | |

| 6 | Book of Psalms | Warren | |

| 7 | Stuart’s Cromwell’s Bible | Warren | |

| 8 | Freedmen’s Bible | Fisk University Bible | Warren |

| 9 | Second Inaugural Bible | Warren | |

| 10 | Anderson Cottage Bible | Lincoln’s Cottage Bible | Barton |

| 11 | Carter E. Prince Testament | Barton | |

| 12 | Charles V. Merrill Bible | Barton | |

| 13 | Robert Turner Bible | Author | |

| 14 | Dennis Hanks Bible | Author | |

| 15 | Amos S. King Bible | Author | |

| 16 | Noyes H. Miner Bible | Author |

The Thomas Lincoln Bible

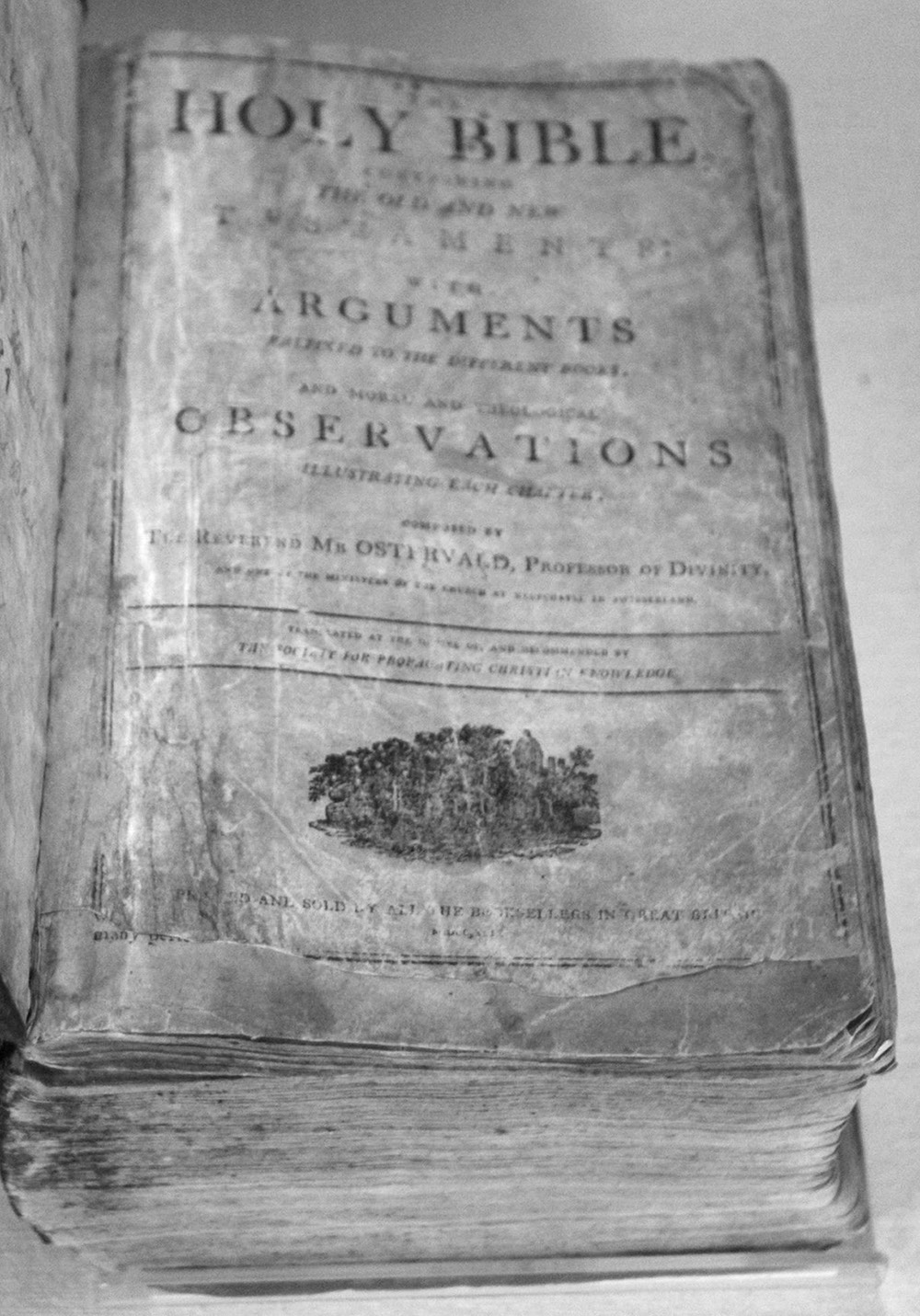

I will begin with what Warren called Lincoln’s “mother’s Bible,” but in this article I will refer to it as the Thomas Lincoln Bible. It was printed in 1799 in Great Britain, and is the oldest Bible associated with the president. According to a National Park Service (NPS) fact sheet, the Thomas Lincoln Bible is approximately 6.5 inches wide, 9 inches high, and 3.5 inches deep. It contains not only the Old and New Testaments but also the books of the Apocrypha. It has reference notes on each page that were translated from French to English in 1744 by the Reverend Jean Frederic Ostervald, pastor of the Swiss Reform Church in Neufchatel, Switzerland. The NPS fact sheet says that the Ostervald Bible was “[r]ecommended by all the Bible societies of the day, [and] this edition found its way into many homes in England and America.”[10] Although the Thomas Lincoln Bible is usually referred to as a Geneva Bible, the text as translated is the King James version.[11]

It is not known when the Thomas Lincoln Bible was acquired, but Barton suggested, on rather thin evidence, that it might have been purchased by Thomas Lincoln in 1806—shortly after he and Nancy Hanks were married in Washington County, Kentucky.[12] Although we cannot be certain that Thomas really bought this Bible then, it is not unlikely. He and Nancy were people of strong religious faith, and it was common for wilderness families to own at least a Bible, even if they possessed no other books.

According to testimony from Nancy Lincoln’s cousin Dennis Hanks, “Lincoln’s mother learned him to read the Bible—study it & the stories in it and all that was morally & affectionate [in] it, repeating it to Abe & his sister [Sarah] when very young.”[13] In addition, Abe probably “learned to read” using a Bible at school. Beginning when he was six years old, he attended two brief sessions of school in Kentucky, where the “masters” frequently used a Bible for reading lessons.[14]

An unresolved question is whether the Thomas Lincoln Bible was the one from which Nancy taught young Abe how to read. If purchased by his father in 1806, it probably would have been this one. But according to Dennis Hanks, Nancy used a different Bible. Hanks, along with Nancy’s aunt and uncle, Elizabeth and Thomas Sparrow, were neighbors of the Thomas Lincoln family in Kentucky. In the winter of 1816–17, about the time Abe turned eight years old, Thomas moved his family from Kentucky to the community of Little Pigeon Creek in Indiana. The Sparrows and Hankses soon followed them. After Nancy Lincoln and the Sparrows died of the “milk sick” in late September and early October of 1818, Hanks moved in with Thomas Lincoln and his two children.

About a year after Nancy’s death, Thomas Lincoln traveled to Kentucky, married a widow named Sara Bush Johnston, and brought her and her three children back to Indiana. Recalling this event, Hanks said that Thomas Lincoln “brought the [Thomas Lincoln] Bible in 1818—or 19.”[15] If this is correct, it would mean that Nancy had not used the Thomas Lincoln Bible to teach Abe to read in Kentucky.

Regardless of whether Lincoln first learned to read from the Thomas Lincoln Bible in Kentucky or didn’t read it until he was ten years old in Indiana, it is certain that Abe, as a child and teenager, was familiar with this Bible. He had use of the Thomas Lincoln Bible until he was twenty-two years old, when, after he helped his family move to Macon County, Illinois, he left them and moved to New Salem.

Lincoln resided in New Salem, Illinois, from 1831 to 1836, living with various townspeople and working at several jobs such as store clerk, postmaster, volunteer soldier, and surveyor. Lincoln decided to enter politics while in New Salem, and he was elected to the lower house of the Illinois state legislature in 1834.

A voracious reader in the 1830s, he borrowed books on subjects such as law, literature, grammar, history, and science. He also read works notorious at the time such as Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason, Constantin de Volney’s The Ruins, and David Hume’s Essays.[16] All three of these were considered heretical books by most Christians in Lincoln’s day, and his reading of them fueled the commonly held belief in New Salem that he was a skeptic of Christianity. It is true that Lincoln rarely attended religious services while he lived in New Salem (there was no church), and it is possible that he did not have a Bible of his own either in New Salem or during the early Springfield years.

In 1837 Lincoln was admitted to the Illinois bar and moved from New Salem to Springfield to begin what he called his “experiment” as a lawyer. Lincoln’s star rose quickly, both professionally and socially. Within three years of his move he became engaged to the well-educated, mercurial Springfield socialite Mary Todd. After a stormy courtship, which included a breakoff of their engagement in early 1841, Lincoln reconsidered and married Mary in November 1842. Their lives became a whirlwind of work, local politics, and raising children. Robert was born in 1843, Eddy in 1846, Willie in 1850, and Tad in 1853.

Meanwhile, Lincoln’s parents and extended family had moved to Charleston, Illinois, in 1831. He saw them only when his obligations as a lawyer took him to that part of the state.[17] When Thomas Lincoln died on January 17, 1851, Lincoln did not go to his father’s funeral, informing his stepbrother that Mary was sick and needed him at home after the recent birth of Willie. Four months later, however, Lincoln went to visit his stepmother in Charleston. During that visit, on May 17, 1851, he wrote the dates of births, deaths, and marriages of his extended family members on two blank pages in the Thomas Lincoln Bible.[18]

Although it would have been reasonable for the only surviving child of Thomas Lincoln to keep his father’s Bible,[19] he probably did not do so, for the following reasons: (1) Most of the births and deaths Lincoln recorded in the Thomas Lincoln Bible were Johnston family members, and the births and deaths of his own children were not included. It would have been strange if he had written down a record of his stepmother Sarah’s family and then taken the Bible with him. (2) Two entries on the bottom of one of the pages, in pencil, were not in Lincoln’s hand. They were for births and deaths of Johnston family members in 1850, 1853, and 1854. (3) Lincoln’s wife, Mary, would have had little or no interest in a Bible with the births and deaths of the Johnston family. She had never met Lincoln’s parents and had almost no interaction with members of the Johnston and Hanks families.[20] (4) Lincoln did not have a need for the Bible. As will be seen, the Lincolns probably had at least two other Bibles in Springfield.

Within a few years of his father’s death, Lincoln’s political career became increasingly important. After Stephen A. Douglas pushed Congress to pass the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which permitted slavery to expand in the western territories, Lincoln became indignant. In his opposition to the measure, he based his political arguments on passages in the Bible and the Declaration of Independence. He ran for the United States Senate in 1855, and after losing that race, ran again in 1858 against Steven A. Douglas. He lost his second bid for the Senate also, but his moral arguments against slavery inspired many in the northern states, and in November of 1860 he won the presidency.

Before leaving Illinois to take the presidential office, Lincoln visited his stepmother again, on January 31, 1861.[21] This turned out to be his last visit with her and the Johnston and Hanks family relatives in Coles County, Illinois. Did he want to take the family Bible for use in the inauguration ceremony? If he did, this was his last chance. Eleven days later he boarded a train bound for Washington.

As it turned out, Lincoln did not take the oath of office with a personal Bible. The reason was supposedly that his personal Bible was not available on Inauguration Day. But even if the Thomas Lincoln Bible was not used in the inauguration, the question remains whether Lincoln took his father’s Bible to Washington. This question endures because two witnesses reported that in the White House the president used a Bible that was similar in description to the Thomas Lincoln Bible. These witnesses were a sixteen-year-old girl and a forty-four-year-old nurse.

In 1861 sixteen-year-old Julia Taft was an unofficial babysitter in the White House for her younger brothers and their companions, Willie and Tad Lincoln. As a result, she spent a great deal of time in the family quarters of the Executive Mansion. She later wrote a book that included some interesting observations of the president’s mannerisms in the White House. Referring to Lincoln’s Bible reading, she wrote, “The big, worn leather-covered book [my italics] stood on a small table ready to his hand and quite often, after the midday meal, he would sit there reading, sometimes in his stocking feet with one long leg crossed over the other, the unshod foot slowly waving back and forth, as if in time to some inaudible music”[22] But was this “big, worn leather-covered” Bible that Taft refers to the Thomas Lincoln Bible? William Jackson Johnstone, author of Abraham Lincoln, the Christian, states that “Mr. Lincoln used it [referring to the Thomas Lincoln Bible] while in the White House.”[23] To support Johnstone’s statement he cites a very credible witness, nurse Rebecca Pomroy.

In February 1862 the superintendent of Washington Nurses, Dorothea Dix, chose Rebecca Pomroy to go to the White House and help the Lincolns care for their two sons, who had come down with typhoid fever. Unfortunately, the doctors were unable to save Willie, who died on the 20th. After Willie’s death, Pomroy remained for some time to care for Tad and Mary. Regarding her time in the White House, she wrote, “It was his [Lincoln’s] custom, while waiting for lunch, to take his mother’s old worn Bible [my italics] and lie on the lounge and read. One day he asked me which book I liked to read best, and I told him I was fond of the Psalms. ‘Yes,’ said he, ‘they are the best, for I find in them something for every day in the week’”[24]

Pomroy remembered that sometimes when Lincoln was relaxing, he would read to her. She recalled, “Sometimes it was Shakespeare, of which he had a most profound appreciation, often reading aloud, in beautifully modulated accents, the thoughts that charmed him most. Then it would be the old family Bible of his mother’s, persuading him with an eloquence beyond that of words, to hold on through the struggle, as she, poor woman, had done, till victory should come.”[25]

Sometime after Pomroy left the White House, Lincoln visited her at the Washington hospital where she worked, and later asked her on two more occasions to come back to the Executive Mansion to care for Mary. Later in the war, when Lincoln directed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to appoint Pomroy’s son to a second lieutenancy in the Army, he described her as “one of the best women I ever knew.”[26]

How Pomroy reached the conclusion that the Bible Lincoln read was “his mother’s” she does not say. It is possible this came up during conversations she and Lincoln had about the Bible and prayer. Although Pomroy’s testimony is an important statement that cannot be casually dismissed, there is some difficulty accepting at face value that what she called “his mother’s old worn Bible” was the Thomas Lincoln Bible.

This skepticism is due to events which transpired after Lincoln’s death. On July 13, 1865—three months after Lincoln’s assassination—Colonel Augustus Chapman wrote a letter to Lincoln biographer Josiah Gilbert Holland in which he revealed, “I have an old family bible of A. Lincoln’s Father and the correct dates of the Birth and Death of the entire family and which each were born and died.”[27] Chapman was the husband of Harriet Hanks, daughter of Dennis Hanks. Dennis had married Lincoln’s stepsister Sarah Elizabeth Johnston, so Chapman was undoubtedly referring to the Thomas Lincoln Bible.

If the Thomas Lincoln Bible had been in the White House during Lincoln’s presidency, it is highly unlikely that Chapman, who lived with the Johnston family in Charleston, Illinois, would have been able to acquire it only three months after Lincoln’s death.[28] After her husband’s assassination, Mary Lincoln was in such an agitated state of mind that it took her more than a month to pack up and leave the Executive Mansion. When she left, she and her sons moved to Chicago. Since she had almost no relationship with the Johnston and Hanks families, it is unlikely she would have given the Thomas Lincoln Bible to them so quickly. Also, as will soon be seen, future correspondence between her son Robert and Dennis Hanks indicates that Robert knew nothing about the Thomas Lincoln Bible.

On September 8, 1865, William H. Herndon wrote a memorandum about a meeting he had in Charleston, Illinois, with Lincoln’s stepmother, Sarah. In that meeting, Sarah showed Herndon her “old family bible dated 1819”[29] which “has Abes name in it.”[30] The day after this interview with Lincoln’s stepmother, on September 9, 1865, Herndon “copied from the bible of Lincoln—made in his own hand writing—now in the possession of Col Chapman—ie the leaf of the Bible—now in fragments Causing me trouble to make out—pieces small—worn in some man’s pocket.”[31] What “some man” [Dennis Hanks] had done was to tear out of the Thomas Lincoln Bible the two leaves that had Lincoln’s handwritten notes of births and deaths.[32] When Herndon saw them, the removed leaves—in addition to the Bible—were still in the possession of the Johnston and Hanks families.

Probably because he was interested in eventually selling the family record, on October 17, 1866, Dennis Hanks wrote and signed an affidavit stating, “I hereby certify that the specimen of handwriting herewith presented to Gen. Chas. Black are the genuine work of Abraham Lincoln late president of the U. S. and that the leaf of the apocrypha is of the family Bible and record of the Lincoln family of which he the said Abraham was a scion.”[33]

In 1872 Hanks sent this affidavit, along with the leaves of the family record, through an intermediary to Robert Todd Lincoln. On December 4 of that year, Robert Lincoln wrote to Dennis that he had been shown by “a gentleman” (probably the General Black referred to in Hanks’s affidavit) the leaf and accompanying affidavit certifying the family record had been written in Robert’s father’s script.[34] Robert told Hanks that he thought he “was mistaken” and it was not in his father’s handwriting. He asked Hanks “how and when and where” he got the leaf and if he knew where the Bible was from which it was taken.[35]

Hanks evidently responded to Robert on January 15, 1873, and Robert again wrote to Hanks on January 17, saying, “Your letter of the 15th is received. You say the Bible from which you took the record is where you can get at it. I wish the next time you have a chance you would see if a piece of the record is not still in the Bible. The part here has one corner torn off.”[36]

Unfortunately, after the January 17 letter, no further correspondence between Robert and Dennis Hanks has been found in the Robert Todd Lincoln papers, so evidently he decided to return the leaves to Hanks and drop his inquiry into both the Thomas Lincoln Bible and the family record.[37]

Through a series of events,[38] the family history leaves from the Thomas Lincoln Bible came into the possession of the Chicago History Museum, where their damage was repaired and where they are carefully preserved today.[39] The Thomas Lincoln Bible was kept by the Johnston and Hanks families until 1893, when it was sold to the “Lincoln Log Cabin Company” for exhibition at the Chicago World’s Fair.[40] It was then purchased by Gardiner Hubbard of the Memorial Association of the District of Columbia for $125. Hubbard presented it to Col. Osborn Oldroyd, a Lincoln collector who kept an assortment of Lincoln memorabilia on display at the Petersen House in Washington, where Lincoln died.[41] The Bible remained in the Petersen house until 1926, when it was acquired by the U.S. government and moved to the newly created Lincoln Museum in Ford’s Theatre.[42] It was displayed there until late 1958, when the National Park Service transferred it to the Lincoln Birthplace in Hodgenville, Kentucky.[43] The Thomas Lincoln Bible had sustained a great deal of damage but was repaired by the National Park Service in 1998.[44] Today the Thomas Lincoln Bible is on display in a sealed case at the Lincoln Birthplace in Hodgenville.

The Lucy Speed Bible

In late summer 1841 Abraham Lincoln, then 32, made a trip from Springfield to Farmington, Kentucky, to visit his best friend, Joshua F. Speed. Speed had returned to Farmington from Illinois in early 1841 to take over the management of the family estate. Lincoln and Speed had similar melancholy temperaments and for years had constantly sought the other’s advice about relationships with women and potential marriages. Lincoln had broken off his engagement with Mary Todd in January 1841, and, needing some “cheering up” from his old friend, spent six weeks with the Speed family. During that visit, Joshua’s mother, Lucy Speed, presented Lincoln with an Oxford edition of the King James Bible, and encouraged him to read it.[45] Lucy’s decision to give Lincoln a Bible is an indicator that he may not have had one of his own at that time.

After he returned to Illinois, Lincoln wrote to Joshua’s half-sister, Mary Speed, in Farmington. He said, “Tell your mother that I have not got her “present” [the Oxford Bible] with me; but that I intend to read it regularly when I return home. I doubt not that it is really, as she says, the best cure for the “Blues” could one but take it according to the truth.”[46]

The Lucy Speed Bible is not mentioned again until October 3, 1861, when President Lincoln sent Lucy a picture of himself that was inscribed: “For Mrs. Lucy G. Speed, from whose pious hand I accepted the present of an Oxford Bible twenty years ago.”[47] Lincoln’s description of it as an Oxford Bible rather than my Oxford Bible may indicate that he no longer had it in his possession.

The Lucy Speed Bible has never been found, and very little is known about it. We have no information about when it was printed, its size, or the type of binding. One scholar has suggested that the Lucy Speed Bible may have been used by Lincoln in the White House.[48] This is certainly within the realm of the possible, but without oral testimony or other corroborative evidence, this statement is no more than conjecture.

Still, Lucy Speed’s gift may have truly made a difference in Lincoln’s life. It is noteworthy that the Collected Works of Lincoln shows only three occasions before 1841 (the May 7, 1837, letter to Mary Owens; the January 27, 1838, Lyceum Address; and the December 26, 1839, Speech on the Sub-Treasury) when Lincoln quoted or alluded to Scripture. But after receiving Lucy’s Bible in late 1841, from 1842 to 1850 he referenced Scripture in twelve separate communications.

The Mary Lincoln Bible

In his Lincoln Lore article, Warren briefly described what he called the Mary Todd Lincoln Bible, which I will refer to as the Mary Lincoln Bible.[49] In 1951 Barton wrote:

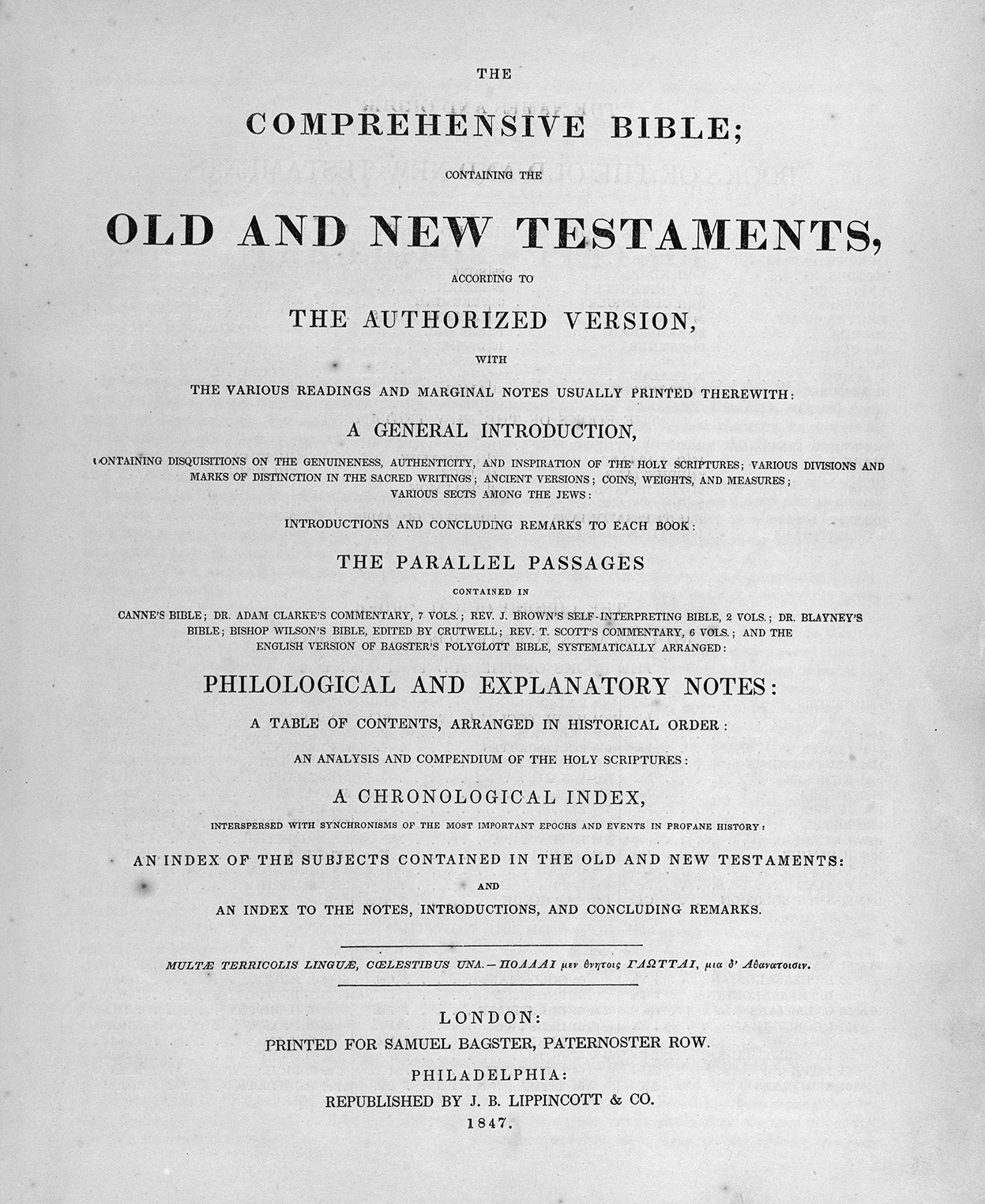

In April 1928, the widow of Robert Todd Lincoln presented to the Library of Congress the Lincoln Family Bible. According to its title page, “The Comprehensive Bible” was printed in London for Samuel Bagster and republished in Philadelphia for J. P. Lippincott and Company, in 1847. Like all family Bibles and presentation Bibles of the period, it contains many steel engraved illustrations. It is a large morocco-bound volume, with the name “Mary Lincoln” and considerable decorative tooling appearing in gilt on the cover. It is on exhibition in the Library of Congress, and the visitor may read the Family Record, which begins in Abraham Lincoln’s hand-writing and continues with entries written by his son.[50]

Today the only update that needs to be made regarding the Mary Lincoln Bible is that it is 10 inches wide, 11.5 inches high, and 3.5 inches deep—too large and heavy for practical, day-to-day use. Unlike the Thomas Lincoln Bible, the births, deaths, and marriages written by Lincoln and his son Robert cover only Lincoln family members. The Mary Lincoln Bible is now in the Abraham Lincoln Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. It is no longer on permanent display, as it was when Barton wrote about it.[51]

First Inaugural Bible

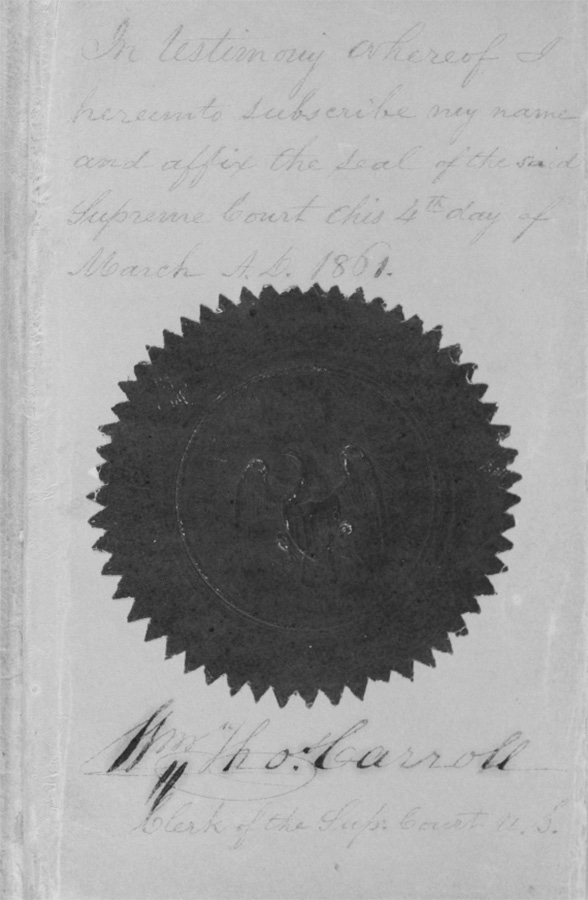

Warren wrote that the Bible used in Lincoln’s first inaugural ceremony was, at the time of his writing, in possession of the Library of Congress and on display there. Warren also indicated that the following inscription appears on the inside of the front cover[52] and following page:

Supreme Court of the United States:

I, William Thos. Carroll, Clerk of the said court do hereby certify that the preceding copy of the Holy Bible is that upon which the Honble. R. B. Taney, Chief Justice of said Court, administered to His Excellency, Abraham Lincoln, the oath of office as President of the United States, on the day of the date her[e]of at the Capitol of the United States in the City of Washington and District of Columbia (being the seat of the National Government of the said United States).

In testimony whereof I hereinto subscribe my name and affix the seal of the said Supreme Court this 4th day of March A. D. 1861.[53]

In 1951 Barton added the following details about what transpired during the first inaugural ceremony:

According to [John G.] Nicolay and [John] Hay, Chief Justice Taney arose, the clerk opened his Bible, and Mr. Lincoln, laying his hand upon it, with deliberation pronounced the oath. Miss Tarbell [a Lincoln historian in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries] writes of “the President saluting the Bible with his lips.” No record is known to exist of a particular passage, if in fact there was one, touched by the President. Two markers, of narrow white silk ribbon, are found placed, perhaps only by chance, one at Deuteronomy 31, the other at Hosea 4.[54]

Barton described the First Inaugural Bible as “no more than four by six and a little more than an inch in thickness, bound in dark crimson plush with a small metal plate on the front cover, engraved ‘Holy Bible.’”[55] Barton corrected Warren’s previous misstatement that Carroll’s certification of the Bible’s authenticity and the seal of the Supreme Court was on the “inside of the front cover and following page” by stating on “the flyleaf at the end, running over to the inside of the back cover, is a certification, to which the seal of the Supreme Court is affixed, made by William Thomas Carroll, clerk of the court.” Barton also mentioned that the flyleaf at the beginning of the volume bore this notation: “To Mrs. Sally Carroll, from her devoted husband, Wm. Thos Carroll, March 4, 1861.”[56]

Mr. and Mrs. Carroll, however, must have changed their minds about keeping the prestigious memento, since they eventually returned it to the Lincoln family. Robert’s wife, Mary, donated it to the Library of Congress in 1928.[57]

Today the First Inaugural Bible is in the Rare Books and Special Collections room at the Library of Congress. It is a King James Bible printed by the Oxford University Press in 1853. The two white ribbons that Barton reported still mark the Deuteronomy 31 and Hosea 4 chapters. Since Lincoln’s assassination, two other presidents have used this Bible for their inaugural ceremonies: Barack Obama in 2009 and 2013, and Donald J. Trump in 2017.

Pocket New Testament

Barton mentions that there are “several anecdotes in print” about Lincoln’s making use of a pocket New Testament, giving the most credence to a story told by Lincoln acquaintance Newton Bateman in Josiah Gilbert Holland’s biography Life of Abraham Lincoln.[58] Another account that includes the pocket testament comes from Frances B. Carpenter, the artist who spent time in the White House and wrote an invaluable book about his experience. Carpenter stated in a letter to William H. Herndon on December 24, 1866, that John Jay of New York told him “not three weeks ago” of an experience while traveling to Norfolk, Virginia, on a steamboat with the president. Lincoln on one occasion had “disappeared,” and when Jay passed a corner in an “out of the way place” on the steamboat “he came upon Mr. Lincoln, reading a dog-eared pocket copy of the New Testament all by himself.”[59]

The whereabouts of this pocket New Testament today is not known.

Book of Psalms

Warren reported in Lincoln Lore, “A Book of Psalms is said to have been much read by Abraham Lincoln, and after his death his widow presented it to Hon. William Reid, U. S. Consul at Dundee, Scotland. It was printed in ‘Great Primer’ type by the American Bible Society in 1857 and contains 212 pages. Bound in a black leather cover it bears in gold letters ‘Book of Psalms’ and beneath the title the name ‘Abraham Lincoln.’ On the cover is also the verse, ‘Blessed is the man that maketh the Lord his trust and respecteth not the proud, nor such as turn to lies.’” Warren wrote that the book was privately owned in 1940.[60]

There has been no further information on this book. If it exists, it is presumably privately owned.

Stuart’s Cromwell’s Bible

Warren wrote in his Lincoln Lore article in 1940, “Once when George H. Stuart, esq. of Philadelphia was visiting at the White House he offered Mr. Lincoln a book. According to Mr. Stuart, Mr. Lincoln ‘rose from his chair, read the title, expressed great pleasure in receiving it, and promised to read it.’ The title of the book was Cromwell’s Bible, which contained a selection from scriptures.”[61] Barton commented in 1951, “The source of [Warren’s] information is not given, and presumably the volume in question is not known to exist.”[62]

The evidence that Lincoln had a connection with the so-called Cromwell’s Bible is very thin, so thin, as a matter of fact, that it suggests a quip from Lincoln himself, who at the sixth debate with Douglas in Quincy, Illinois, declared that one of Stephen A. Douglas’s arguments was “as thin as the homoeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had starved to death.”[63]

Fisk University Bible

Warren described what he called the Freedmen’s Bible, which we will refer to as the Fisk University Bible, in this way: “In 1864 a group of colored people from Baltimore Maryland presented Abraham Lincoln with a beautiful Bible, pulpit size, bound in velvet and ornamented with bands of gold. A plate of gold placed on the cover bore this inscription ‘To Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, the Friend of Universal Freedom. From the loyal colored people of Baltimore as a token of respect and gratitude. Baltimore, July 4, 1864.’” Lincoln acknowledged the receipt of this book with a short address from which the following excerpt is taken: “In regard to this great book, I have but to say it is the best gift God has given to man.”[64]

Barton included some details about the ceremony and what was said by the participants, then concluded with the statement that “so far as this author is aware, the Freedmen’s Bible has disappeared.”[65] Barton was not aware that in 1916 Robert Todd Lincoln had given this beautiful Bible to Fisk University of Nashville, Tennessee.[66] Today it is kept on display in Fisk University’s John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library.

The Second Inaugural Bible

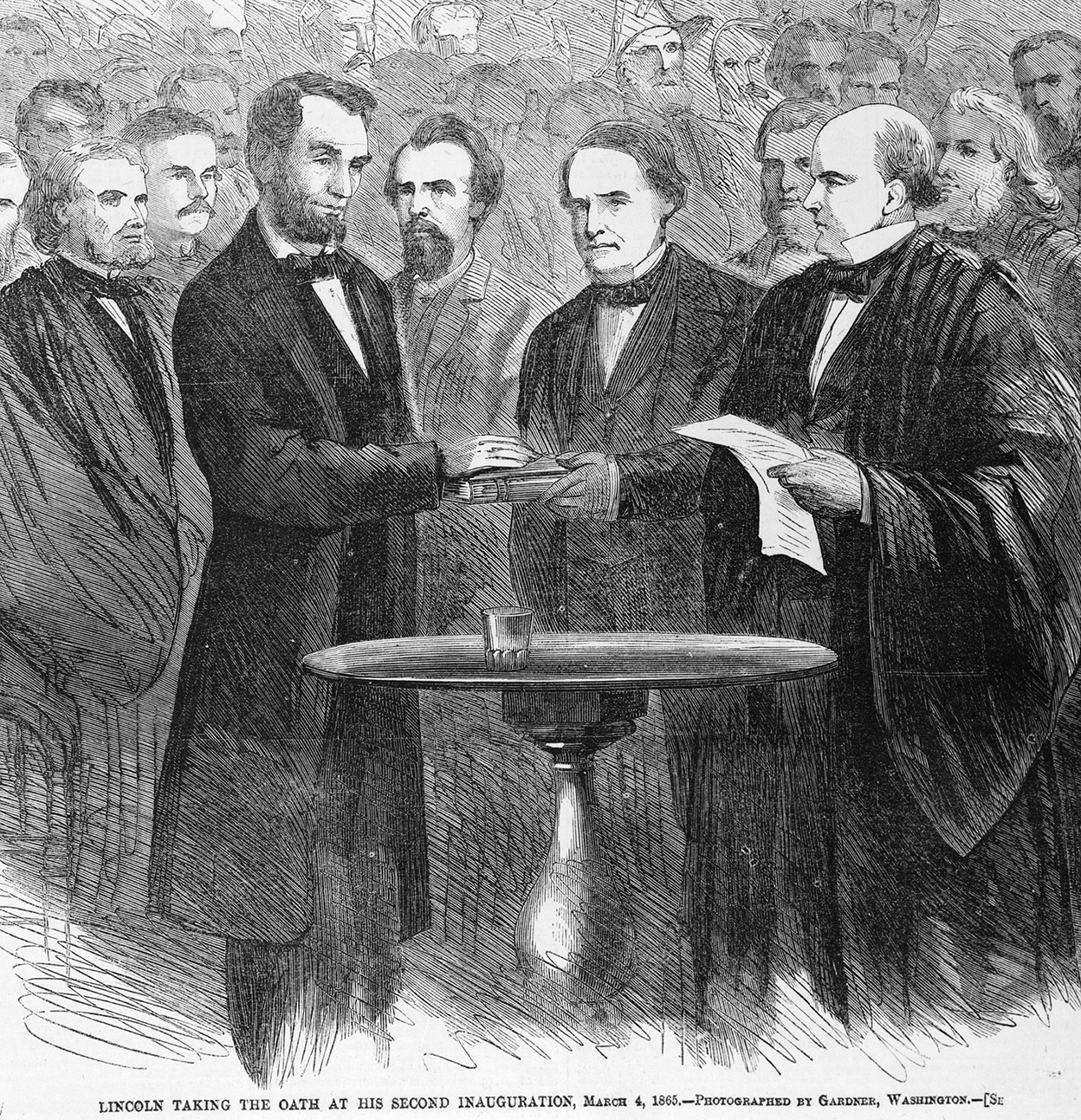

In Warren’s Lincoln Lore article about the Bible used in the second inaugural ceremony in 1865, he wrote that Lincoln placed his left hand on the Bible, swore the oath, and kissed the 27th and 28th verses of the fifth chapter of Isaiah. Warren also indicated that “the editor of Lincoln Lore has been unable to find out where the Bible is at this time.”[67]

In Robert Barton’s 1951 update on the Second Inaugural Bible, he quoted Warren and then, hoping to add a little more clarity to the mystery of the Bible’s fate, confused the issue more by adding a puzzling note from the American Bible Society, which cited an April 6, 1945, letter from the Library of Congress that stated “at the time of Lincoln’s Inauguration in 1865 the Bible was opened at the following passages: Matthew 7:1, Matthew 18:7, and Revelation 16:7.” This was probably an erroneous statement, since it disagrees with details of other accounts of the ceremony. Barton admitted, “It is not understood how the Bible could be opened in three places.”[68]

Today, a more complete account of what happened at the inaugural ceremony is available. According to Benjamin Franklin Morris, who wrote the Memorial Record of the Nation’s Tribute to Abraham Lincoln, 1865, the second inaugural ceremony transpired as follows:

He [Lincoln] stood on the eastern portion of the Capitol, and in the presence of many thousands of his fellow-citizens took the oath of office. At the request of Chief Justice Chase, who administered the oath, D. W. Middleton, Clerk of the Supreme Court of the United States, handed an open Bible to the President, who laid both his hands upon it, and slowly and solemnly repeated the words of the oath, first pronounced by the Chief Justice, viz: “I, Abraham Lincoln, do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. So help me God.”

The President then reverently pressed his lips upon the sacred pages, and handed the Bible back to Mr. Middleton, who instantly marked the verses touched by the President’s lips. On examination, he [Middleton] found them to be the 26th and 27th verses of the fifth chapter of Isaiah, commencing ‘And he will lift up an ensign to the nations,’ &c. . . .”

The Bible thus opened and used for the inauguration was handed to the wife of the President, who will doubtless preserve it as a sacred family memorial of that most solemn and impressive scene.[69]

Chief Justice Chase wrote to Mary Lincoln:

Will you oblige me by accepting the Bible kissed by your honored husband, in taking today, for the second time, the oath of office as president of the United States.

The page touched by his lips is marked.

I hope the Sacred Book will be to you an acceptable souvenir of a memorable day.[70]

Figure 4. Harper’s Weekly image of Lincoln’s second swearing-in ceremony. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Figure 4. Harper’s Weekly image of Lincoln’s second swearing-in ceremony. Courtesy Library of Congress.But what was the fate of the Second Inaugural Bible? Even though Morris was certain that the president’s wife “will doubtless preserve it as a sacred family memorial,” it has never been found.

In late 1908 Robert Todd Lincoln responded to an inquiry from Abram Wakeman about, among other things, the location of the Second Inaugural Bible. Regarding that Bible, Robert wrote:

As to the Bible, neither Mrs. Lincoln [Robert’s wife, Mary] or myself can remember ever to have seen it. My mother’s personal belongings came to me after her death in 1882 and anything of interest to them has been carefully preserved by us, but the Bible in question is not among them. It is entirely possible that she may have presented it to some friend in her life-time, but of this I simply know nothing.[71]

In 1917 Lincoln biographer Ervin Chapman concurred that Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Bible was lost and that “the most diligent search, extending over a period of many years, has failed to find it.”[72] At least one Lincoln scholar speculated that the second inaugural ceremony might possibly have been conducted with the same Bible as the first one.[73] This is probably not the case, because according to Morris, the Second Inaugural Bible was marked at the 27th and 28th verses of the fifth chapter of Isaiah. In an inspection of the First Inaugural Bible at the Library of Congress, I found no markings on that page.

It is also doubtful that Lincoln’s personal Bible was used for the second inaugural ceremony for the following reason. In Chase’s letter to Mrs. Lincoln, he asked her to “oblige” and accept “the Bible kissed by your honored husband,” and that he hoped “the Sacred Book will be to you an acceptable souvenir of a memorable day.” This was oddly phrased if it had been Lincoln’s personal Bible. Chase probably would have told her he was returning the president’s personal Bible, not “an acceptable souvenir.”[74] Today, the fate of the Second Inaugural Bible remains unknown.

Bibles Added by Barton

In addition to Warren’s list of historic Lincoln Bibles, in 1951 Barton suggested that three more Bibles should be added. He referred to these as the Anderson Cottage Bible, the Carter E. Prince Testament, and the Charles W. Merrill Bible.

Lincoln’s Cottage Bible

During the summer months of the war, the Lincoln family frequently stayed in what was then referred to as the Anderson Cottage (today known as Lincoln’s Cottage) at the Soldiers’ Home, which was a military institution three miles north of the Capitol. Barton wrote that on one evening Lincoln’s friend Joshua Speed visited Lincoln in the cottage. Speed recalled,

As I entered the room, near night, [Lincoln] was sitting near a window intently reading his Bible. Approaching him I said, “I am glad to see you so profitably engaged.” “Yes,” said he, “I am profitably engaged.” “Well,” said I, “if you have recovered from your skepticism, I am sorry to say that I have not.” Looking me earnestly in the face, and placing his hand on my shoulder, he said, “You are wrong, Speed; take all of this book [the Bible] upon reason that you can, and the balance on faith, and you will live and die a happier man.”[75]

Barton used this incident to suggest, without specific evidence, that there was an “Anderson Cottage Bible.” Today, however, there is no evidence that a separate Lincoln Bible was ever kept there.

Carter E. Prince Testament

Barton wrote that Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg, “by describing it in one volume and illustrating it in another, identifies a Testament which, by association at least, might be included in a list of Lincoln Bibles. It is a pocket Testament with a bullet imbedded in it—a little book which saved the life of Carter E. Prince, of the 4th Maine Volunteers, in the Battle of Cold Harbor.”[76] Barton also wrote, “No evidence of President Lincoln’s actual connection with this Testament or incident [was] given” by Sandburg, and this is still the case.

Charles W. Merrill Bible

There is, however, a pocket New Testament with a bullet in it that is genuinely associated with President Lincoln. For this book Barton wrote:

Among the treasured exhibits in the Essex Institute, at Salem, Mass., there is a pocket Testament which, like the one just mentioned, has a bullet firmly lodged in it. Companion to it is a Bible, of similar size, which was presented to the soldier to replace the damaged volume. Both belonged to Pvt. Charles W. Merrill. At the Battle of Chancellorsville (May 2–3, 1863) Private Merrill was fortunate indeed that the bullet meant for his heart lodged instead in his little book. Somehow news of the miraculous escape reached President Lincoln. Quite conceivably he was shown the book; we can well imagine that he handled and examined it, for within a week he sent a new book, a Bible not a Testament, to Private Merrill. On exhibition now, it shows the signs of use; but it must have had a very fine appearance when the soldier received it—a handsome little book, bound in red board covers with a brass clasp. And the personal message from his Commander in Chief must have made him proud indeed, for written on the inside cover was the inscription: “For Charles W. Merrill, of 19th Massachusetts. May 8, 1863. A. Lincoln.”[77]

Today, Private Merrill’s Testament and the Bible President Lincoln inscribed to him are kept in the Peabody Essex Museum’s Phillips Library Collection in Rowley, Massachusetts.[78]

Introduction of Four Previously Unidentified Lincoln Bibles

In addition, four previously unidentified Bibles should be added to the list of Bibles associated with Lincoln.

Robert Turner Bible

In May of 1958 Lincoln Isham, a great-grandson of Abraham Lincoln, gave to the Library of Congress a Bible that belonged to his family. It was a King James Bible published in Philadelphia in 1854 by Lippincott, Grambo, and Company. The May 1958 issue of the Library of Congress Quarterly Journal of Library Acquisitions described it as “bound in elaborate Victorian style with raised panels over heavy boards, covered with maroon morocco elaborately tooled in gilt. A leather label on the inside front cover reads: ‘Abraham Lincoln & Lady from Robert Turner Baltimore, MD.’” The Journal article also noted, “On the recto of the third flyleaf Mrs. Abraham Lincoln wrote the following inscription: ‘This Holy Bible, is presented to my dear Son’s eldest daughter, by her Affectionate grandmother Mary Lincoln October 16th, 1872.’[79] The son referred to was Robert Todd Lincoln, and the daughter Mrs. Charles [Mamie] Isham, mother of the donor.”[80] Mamie had turned three years old the day before Mary Lincoln presented the Bible to her.

Robert Turner was apparently a merchant in Baltimore. This Bible may have had some sentimental value to Mary Lincoln, because she held on to it for many years and then gave it to her elder granddaughter. It is not known when Mr. Turner gave the Bible to the Lincolns, or whether, as president, Abraham read it. Since this is a large, ornate “presentation” Bible, it is doubtful that it was used extensively in the White House.[81]

Today the Robert Turner Bible is in the Rare Books and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress.

Dennis Hanks Bible

On June 13, 1865, William H. Herndon recorded an interview in which he documented Dennis Hanks’s answers to “8 or 10 interrogations.” In this interview, Dennis made the rather remarkable claim that he “taught Abe his first lesson in spelling—reading and writing—I taught Abe to write with a buzzards quillen which I killed with a rifle & having made a pen—put Abes hand in mind & moving his fingers by my hand to give him the idea of how to write.”[82]

It was two sentences farther into the interview that Hanks said, as noted above, “Lincolns mother learned him to read the Bible—study it & the stories in it & all that was morally & affectionate in it, repeating it to Abe & his sister when very young.” Hanks continued, “Lincoln was often & much moved by the stories. This Bible was bought in Philadelphia about 1801—by my Father & Mother & was mine when Abe was taught to read in it. It is now burned with all property—deeds if any & other records—This fire took place in Charleston—Coles Co Ills Decr. 5th 1864.”[83]

If Hanks is correct, when Abe and his sister were very young, Lincoln’s mother, Nancy, used Dennis’s Bible to teach her children to read, rather than the Thomas Lincoln Bible. As Lincoln scholars consider Hanks’s recollections unreliable, however, we cannot be certain if it was the Dennis Hanks Bible that Lincoln used when first learning to read.[84]

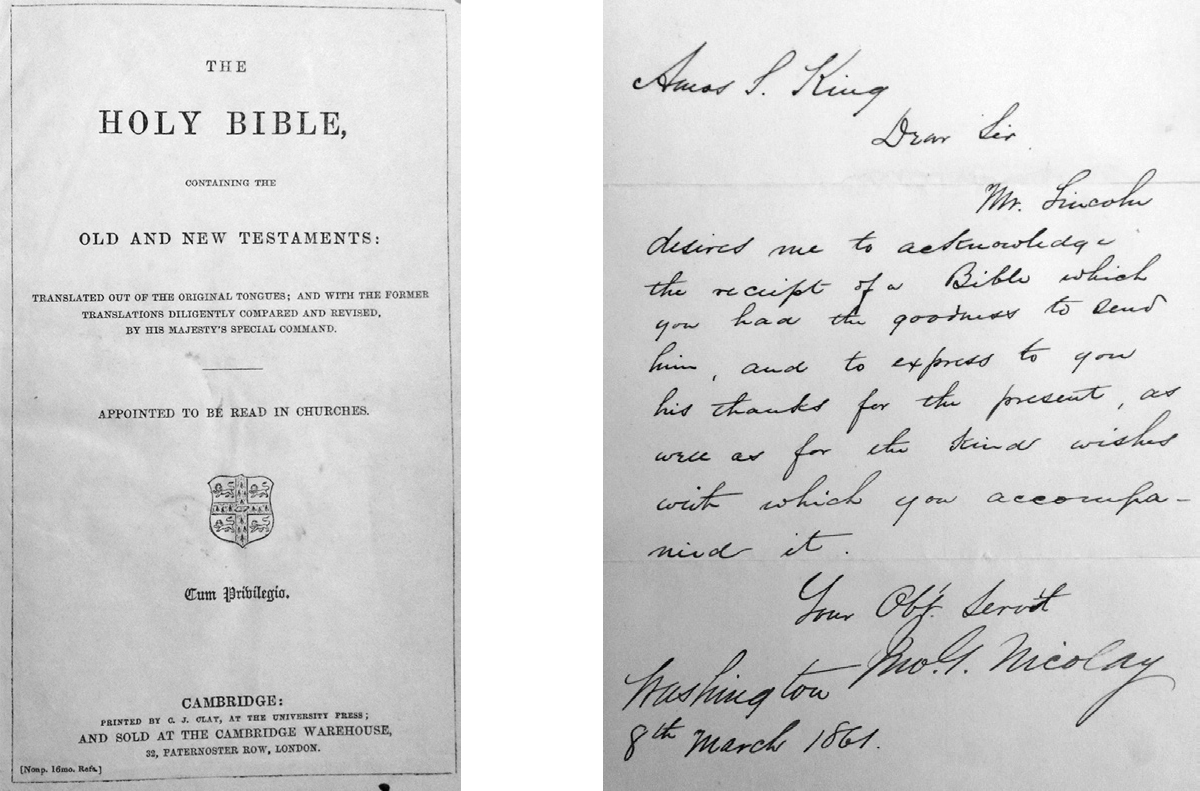

Amos S. King Bible at Hildene

After Mary Lincoln died in 1882, her son Robert inherited from her estate a Bible now known as the Amos S. King Bible. For generations this Bible was kept on the library shelves of the Lincoln family home Hildene, in Manchester, Vermont. In 2009, because of the increased interest in Lincoln Bibles inspired by Barack Obama’s inauguration, Hildene researched the history of the King Bible. It was then determined that the Bible had been an inauguration gift from King to President Lincoln in March 1861.[85]

Amos S. King, a resident of Port Byron, New York, sent Lincoln a Cambridge King James Bible after he read the president-elect’s February 11, 1861, farewell speech to the citizens of Springfield. In his letter to Lincoln, King wrote that he gave the Bible as a small token of the “high esteem and kind regard in which the giver holds the honored recipient.”[86]

On March 8, four days after Lincoln was inaugurated as president, Lincoln’s personal secretary John G. Nicolay sent a note to King: “Mr. Lincoln asked me to acknowledge the receipt of a Bible which you had the goodness to send him, and to express to you his thanks for the present, as well as for the kind wishes with which you accompanied it.”[87]

Figure 6. Hildene Bible title page and Nicolay acceptance letter. Courtesy of Hildene, The Lincoln Family Home, Manchester, Vt.

Figure 6. Hildene Bible title page and Nicolay acceptance letter. Courtesy of Hildene, The Lincoln Family Home, Manchester, Vt.I visited Hildene in June 2018 to examine this Bible. A careful inspection was made to see if there were any markings or hand-written notes in it that might indicate that it had been used in the White House.[88] Although no markings inside the Bible were found, I discovered two noteworthy things about the Bible. First, unlike most of the other Lincoln Bibles that were known to have been in the White House during the war years, it is small—only 4 inches wide, 6 inches high, and 2 inches deep. Second, several pages are dog-eared in the upper right-hand corner. The dog-earing is found on some of the books that Lincoln was fond of reading—every page of the book of Job, and seventeen other pages, including the last chapters of Matthew and the first part of Mark. The dog-earing of the book of Job may be significant because of the testimony of Elizabeth Keckly, Mary Lincoln’s seamstress, who recorded the following event she witnessed in the White House:

In 1863 the Confederates were flushed with victory, and sometimes it looked as if the proud flag of the Union, the glorious old Stars and Stripes, must yield half its nationality to the tri-barred flag that floated grandly over long columns of gray. These were sad, anxious days to Mr. Lincoln, and those who saw the man in privacy only could tell how much he suffered. One day he came into the room where I was fitting a dress on Mrs. Lincoln. His step was slow and heavy, and his face sad. Like a tired child he threw himself upon a sofa, and shaded his eyes with his hands. He was a complete picture of dejection. Mrs. Lincoln, observing his troubled look, asked:

“Where have you been, father?”

“To the War Department,” was the brief, almost sullen answer.

“Any news?”

“Yes, plenty of news, but no good news. It is dark, dark everywhere.”

He reached forth one of his long arms, and took a small Bible [my italics] from a stand near the head of the sofa, opened the pages of the holy book, and soon was absorbed in reading them. A quarter of an hour passed, and on glancing at the sofa the face of the President seemed more cheerful. The dejected look was gone, and the countenance was lighted up with new resolution and hope. The change was so marked that I could not but wonder at it, and wonder led to the desire to know what book of the Bible afforded so much comfort to the reader.

Making the search for a missing article an excuse, I walked gently around the sofa, and looking into the open book, I discovered that Mr. Lincoln was reading that divine comforter, Job. He read with Christian eagerness, and the courage and hope that he derived from the inspired pages made him a new man.[89]

Keckly’s testimony is important for three reasons. First, it is the only account of someone witnessing Lincoln’s reading of a specific book of the Bible. Second, it is the only account in which Lincoln was reading a small Bible. Julia Taft and Rebecca Pomroy both described old, worn Bibles that were either large or “his mother’s,” and various other witnesses mention President Lincoln reading from a Bible, without making any attempt to describe the Bible itself.[90] Third, it is the only account in which Lincoln’s reading of the Bible seems to have had an immediate, noticeable impact on his demeanor.

The dog-earing of Job is also noteworthy because, as mentioned previously, Lincoln was reported to have owned a dog-eared pocket New Testament.[91]

Taking these facts into account, a stronger case can be made for Lincoln’s use of the Amos S. King Bible than for any other known Bible while in the White House.[92] This Bible is now displayed at the Lincoln family estate Hildene, along with the letter from King to President Lincoln and the reply to King from Lincoln’s secretary John G. Nicolay.

Noyes H. Miner Bible

Rev. N. H. Miner, pastor of a Baptist church in Springfield and a neighbor of the Lincolns, apparently received a Bible from Mary Lincoln in 1872, on the day before she gave the Robert Turner Bible to her granddaughter Mamie. The Miner Bible had been given to President Lincoln by a women’s charitable group in Philadelphia during his visit to the Sanitary Fair there on June 16, 1864, and as a heavy presentation Bible thus was inscribed. It certainly reposed in the White House until his death ten months later. Mary Lincoln later had its back inscribed for Rev. Miner, who remained close to her in widowhood.

Rev. Miner’s descendants came forward in June 2019 and gifted the Bible to the Presidential Library and Museum, in Springfield, where it was placed on display.

To summarize, there were at least seven Bibles in the White House at some time during Lincoln’s presidency. There may also have been a pocket New Testament and a book of Psalms used by him.

Although the Mary Lincoln Bible was in the White House, it is doubtful that Lincoln read it very much because it was a large, hard-bound presentation Bible. It bears the distinction of having the marriage, birth, and death dates of the Lincoln family written in it in Lincoln’s and his son Robert’s script. Today it is in the Library of Congress.

It is not known if Lincoln read from the Bible that was used in the first inaugural ceremony while he was in the White House. He may not have, since Supreme Court clerk Thomas Carroll gave this Bible to his wife after the ceremony, and it is uncertain if it was returned to the Lincoln family during the war. Today the First Inaugural Bible is also in the Library of Congress.

The Amos S. King Bible was received by Lincoln at the beginning of his presidency and remained with him throughout the White House years. Lincoln probably read this Bible while he was president. This book is now displayed at Hildene.

It is known that Lucy Speed, mother of Lincoln’s friend Joshua Speed, gave Lincoln an Oxford Bible in the early 1840s. Whether he brought this Bible to the White House is unknown, but the way he referred to it in a letter to Lucy Speed in 1861 may indicate that he no longer had it. This Bible has never been found or identified.

The Robert Turner Bible was given to Lincoln and Mary sometime during their stay in the White House. Like the Mary Lincoln Bible, it is a large presentation Bible and it is not known if Lincoln read it while president. Today it is in the Library of Congress.

The Fisk University Bible was a large presentation Bible given to Lincoln in September 1864. Although its size and ornate design would probably have prevented him from frequently using it, he may have read from it occasionally in the White House. He was known to have shown it to African American abolitionist Sojourner Truth when she visited him in October of 1864.[93] Today it is displayed at the Fisk University Library Special Collections Reading Room in Nashville, Tennessee.

The Bible Lincoln used for his second inauguration ceremony was presumably kept in the White House by Mary Lincoln after she received it from Chief Justice Chase on March 4, 1865. It is unlikely that Lincoln read it much, if at all, in the few weeks he had left in his presidency. For reasons stated previously, it is doubtful that the Second Inaugural Bible was either Lincoln’s personal Bible or the one used in the first inaugural ceremony.[94] It has never been found or identified, probably because Mary Lincoln gave it to a friend or benefactor.

The Charles V. Merrill Bible was inscribed by Lincoln during the Civil War and was presumably in the White House for at least a brief period, but it is not known if Lincoln spent any time reading it. This Bible is now kept in the Peabody Essex Museum’s Phillips Library Collection in Rowley, Massachusetts.

The Noyes H. Miner Bible was evidently in the White House from about June 1864 through Mary Lincoln’s departure in May 1865. It seems possible, if unlikely, that the president read part of it. Today it belongs to the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, in Springfield.

The Cromwell’s Bible and the Dennis Hanks Bible, if they existed, were never in the White House. The Lincoln’s Cottage Bible may have been a personal Bible that Lincoln brought with him when he went to the Soldiers’ Home. The Carter E. Prince Testament had no real affiliation with Lincoln.

In conclusion, there are probably a few more Lincoln Bibles out there—on shelves, on mantels, and in attics of people who are unaware of what they have, or collectors who are reluctant to give them up. Mary may have given away a number of them to friends and allies, such as one the author was recently told of but has not seen: an 1868 gift to her former pastor, the Rev. James Smith of the First Presbyterian Church in Springfield, listed in October 2016 on the website of RR Auction.[95] And, of course there is always that elusive Second Inaugural Bible, perhaps the biggest mystery of all.

In addition to the fate of the Second Inaugural Bible, another big mystery concerning the Lincoln Bibles is whether the old Thomas Lincoln Bible was the one described by White House witness Julia Taft as “big, worn leather-covered” and by White House witness Rebecca Pomroy as his “mother’s old, worn Bible.” For reasons given in this article, it is doubtful that the Thomas Lincoln Bible was in the White House.

It is possible that instead of the Thomas Lincoln Bible, Lincoln used a different personal Bible, one that was “old, worn, and leather-bound,” in the White House. No such Bible has ever been found, however, and it is difficult to conceive of Mary Lincoln giving away this one or losing it, if it was Lincoln’s personal Bible. Robert Todd Lincoln stated that he and his wife “carefully preserved” everything “of interest” of his mother’s personal belongings after her death.[96]

As the National Park Service’s 1998 condition report of the Thomas Lincoln Bible indicates, it sustained significant damage and, although repaired, is considered very fragile.[97] Unfortunately, neither this condition report nor any other documentation that has been found addresses whether the pages of Bible text have any writings, markings, or dates on them.[98] Until the National Park Service allows experts to thoroughly inspect its interior, this Bible cannot offer any additional clues as to whether it was once used in the White House by President Abraham Lincoln.[99] Today the Thomas Lincoln Bible is on display at the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Park in Hodgenville, Kentucky.

Louis A. Warren, “Historic Lincoln Bibles,” Lincoln Lore, no. 567 (February 19, 1940); courtesy of the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Allen County Public Library. Hereafter cited as Warren, Lincoln Lore 567.

Robert S. Barton, How Many Lincoln Bibles? (Foxboro, Mass.: published by the author, 1951). Hereafter cited as Barton, Lincoln Bibles.

Conversation with John Langdon Kaine, in Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, eds., Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1996), 272.

Julia Taft Bayne, Tad Lincoln’s Father (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1931), 184.

“Reply to the Loyal Colored People of Baltimore upon Presentation of a Bible,” Sept. 7, 1864, in Roy P. Basler, ed., Marion Dolores Pratt and Lloyd A. Dunlap, asst. eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 7:542. Hereafter cited as CW.

According to my latest count in the CW. This number does not include Bible passages from Lincoln’s “Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions,” which alone has more than 30 references to Scripture.

Ronald C. White Jr., The Eloquent President: A Portrait of Lincoln through His Own Words (New York: Random House, 2005), 282.

NPS fact sheet, The Lincoln Family Bible, (Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site, NPS, n.d.). Thanks to John George and Stacy Humphreys of the NPS, Hodgenville, for providing access to the NPS ABLI Archives and Museum Collection.

The 1799 Thomas Lincoln (Ostervald) Bible is kept in a sealed case and is unavailable for inspection by historians. But other Ostervald Bibles are available worldwide, and I determined that the text of the Ostervald Bible is King James rather than Geneva. This, after I reviewed passages of the 1799 Ostervald Bible at the University of Chicago Library and the 1793 Ostervald Bible at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield. Thanks to the staff of the Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago, and Lincoln Collection curator James Cornelius and Lincoln historian Christian McWhirter at the presidential library.

Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, eds., Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews, and Statements about Abraham Lincoln (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 37. Hereafter cited as Herndon’s Informants.

The Bible, being one of the most widely available books on the frontier, was frequently used for reading lessons in school. When Lincoln was president, he recalled a humorous incident of his boyhood. When he and his fellow students were taking turns in reading from the third chapter of Daniel, one of the younger students got into trouble with the master for being unable to pronounce some of the Hebrew names. See Louis Warren, Lincoln’s Youth: Indiana Years, 1816–1830 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1991), 83.

Herndon’s Informants, 106. It is possible that instead of Thomas Lincoln brought the Bible in 1818 or 1819, Hanks might possibly have meant Thomas Lincoln bought the Bible at that time. Regardless of the word, Hanks implies that Thomas Lincoln did not possess this Bible until about the time he married Sarah Bush Johnston, and he may mean that it was among her household possessions Thomas and she brought with them from Kentucky. Whether this Bible was acquired in 1806 or 1819, Abraham, born in 1809, would have read from it.

Robert Bray, “What Lincoln Read—An Evaluative and Annotated List,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 28 (Winter 2007), 32, 68, and 77.

Charles H. Coleman, Abraham Lincoln and Coles County, Illinois (New Brunswick, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1955), 133, 135.

Earl Schenck Miers and William E. Baringer, Lincoln Day by Day: A Chronology (Washington, D.C.: Lincoln Sesquicentennial Commission, 1960), 2:54. Hereafter cited as Lincoln Day by Day. See also Coleman, Abraham Lincoln and Coles County, 133, and “Family Record Written by Abraham Lincoln,” [1851?], CW 2: 94–96.

Lincoln’s sister Sarah died giving birth to a son on January 20, 1828. Her son did not survive either.

The only member of the Johnston and Hanks families Mary ever met was Dennis Hanks’s daughter, fourteen-year-old Harriet Hanks. According to Herndon’s Informants, 646, Harriet lived with the Lincolns in Springfield from 1842 to 1844. It is possible that she may not have gotten along well with Mary, although Coleman believes she did (Abraham Lincoln and Coles County, 69–70).

William Jackson Johnstone, Abraham Lincoln, the Christian (New York: Abingdon Press, 1913), 156–57, caption. (Editor’s note: This author changed his surname from Johnson to Johnstone around 1920.)

Anna L. Boyden, Echoes from Hospital and White House: A Record of Mrs. Rebecca R. Pomroy’s Experience in War Times (Boston: D. Lothrop & Co., 1884), 62.

Letter from Augustus H. Chapman to Josiah G. Holland, Charleston, Illinois, July 13, 1865, in Allen C. Guelzo, “Holland’s Informants: The Construction of Josiah G. Holland’s ‘Life of Abraham Lincoln,’” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 23 (Winter 2002), 39n.

An intriguing possibility, albeit remote, comes from the fact that Chapman’s wife, Harriet Hanks, was the one member of the Johnston and Hanks families with whom Mary had a relationship. See supra, note 20 and accompanying text. There might have been a cordial, enduring relationship established by this occurrence, but no evidence of correspondence between Mary and Harriet exists. The earliest known correspondence between Mary and Lincoln’s stepmother, Sarah, is dated December 19, 1867; Mary asks Sarah to accept a gift of “a few trifles.” See Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), 464–65.

What Herndon means by “dated 1819” he does not say. It may be a reference to Thomas Lincoln’s and Sarah Bush Johnston’s marriage date, December 2, 1819, in the family record, which had already been removed from the Bible by Hanks. The internal pages of the Thomas Lincoln Bible cannot be accessed or inspected, so no further clarification of this point is possible.

See Herndon’s Informants, 110–11, for Herndon’s notes from the Lincoln Family [Thomas Lincoln] Bible. See also “Family Record Written by Abraham Lincoln,” [1851?], CW, 2:95n.

According to Jesse Weik, Dennis Hanks “tore out and wore out the Bible record.” See Carl Sandburg, Lincoln Collector: The True Story of the Oliver R. Barrett Lincoln Collection (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1950), 106.

Photocopy of Dennis Hanks’s signed affidavit dated October 17, 1866; courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Birthplace NationL Historic Park (NHP), NPS ABLI Archives and Museum Collection.

Per reference to Gen. Chas. Black in the affidavit. Herndon’s Informants, 512n, says Dennis’s associate might have been John C. Black, a Lincoln associate who had served in the Union army and was practicing law in Champaign, Illinois.

Transcript of letter from Robert Todd Lincoln to Dennis Hanks, December 4, 1872; courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Birthplace NHP, NPS ABLI Archives and Museum Collection.

Transcript of letter from Robert Todd Lincoln to Dennis Hanks, January 17, 1873; courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Birthplace NHP, NPS ABLI Archives/Museum Collection.

Search of the Robert Todd Lincoln papers at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library on October 2, 2017.

William H. Herndon’s associate Jesse Weik, who was collaborating with Herndon on his biography of Abraham Lincoln, obtained the family history leaves from Dennis Hanks in early 1888. According to a January 27, 1888, letter from Jesse Weik to Lincoln memorabilia collector Charles F. Gunther (courtesy of the Chicago History Museum), Weik stated that he had acquired the Lincoln Bible record of family births and deaths. Weik sold the leaves to Gunther. At an unknown date, Lincoln collector Oliver R. Barrett acquired the leaves, probably from Gunther. On February 20, 1952, the Chicago Historical Society purchased the leaves from the Barrett Collection at public auction. See Chicago Daily Tribune, February 21, 1952, col. 8, and Coleman, Abraham Lincoln and Coles County, 59 n23.

Thanks to Ellen Keith, the director of research and access at the Chicago History Museum Research Center, and staff for providing information and access to the Lincoln Family Records.

Date of Johnston and Hanks family sale of the Bible is from the NPS fact sheet, The Lincoln Family Bible. Sale of the Bible was to the “Lincoln Log Cabin Company,” per Ida M. Tarbell, The Early Life of Abraham Lincoln (New York: S. S. McClure, 1896), 38.

William Benham Burton, Life of Osborn H. Oldroyd: Founder and Collector of Lincoln Mementos (Washington, D.C.: privately printed, 1927). On page 16 Burton says, “[T]his Bible was purchased by the late Gardiner Hubbard of Washington at a cost of one hundred and twenty-five dollars and by him presented to Captain Oldroyd.”

May 26, 1958, memorandum from Mr. Stanley W. McClure, Assistant Chief Park Historian, to Mr. T. Sutton Jett, Associate Superintendent, “Comments on the Suggested Transfer of the Thomas Lincoln Bible from the Lincoln Museum to the Abraham Lincoln National Historic Park”; courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Birthplace NHS, NPS ABLI Archives and Museum Collection.

The transfer of the Bible from Washington, D.C., to Hodgenville was authorized in a June 9, 1958, memorandum from the Superintendent, National Capital Parks, to the Chief of Interpretation, National Park Service, and was accessioned by the Lincoln NHP on December 19, 1958. Courtesy of Abraham Lincoln Birthplace NHS, NPS ABLI Archives and Museum Collection.

Sept. 21, 1998, Condition and Treatment Report for the Holy Bible . . . with . . . Arguments . . . and . . . Observations . . . composed by the Reverend Mr. Ostervald, Abraham Lincoln Birthplace NHS, NPS ABLI Archives and Museum Collection.

See Ronald White, A. Lincoln: A Biography (New York: Random House, 2009), 111–12. See also Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) 1:187.

“To Mary Speed,” September 27, 1841, CW, 1:261. His statement “could one but take it according to the truth” is evidence that Lincoln, at this stage in his life, was truly questioning the validity of the Bible.

“Inscription on Photograph given to Mrs. Lucy G. Speed,” October 3, 1861, CW, 4:546.

Edwin D. Freed, Lincoln’s Political Ambitions, Slavery, and the Bible (Eugene, Ore.: Pickwick Publications, 2012), 6.

Barton, Lincoln Bibles, 4. See also “Family Record in Abraham Lincoln’s Bible,” November 4, 1842, CW, 1:304.

Thanks to Michelle Krowl, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress, for access to the Mary Lincoln Bible and help with the physical dimensions.

“Lincoln’s Bibles Given to Country by Widow of Son,” Washington Post, April 22, 1928.

Josiah Gilbert Holland, The Life of Abraham Lincoln (Springfield, Mass.: Gurdon Bill, 1866), 236–37.

Herndon’s Informants, 521. According to Warren in Lincoln Lore no. 567, Jay (probably grandson of Chief Justice John Jay) saw Lincoln on May 4, 1862.

Warren, Lincoln Lore 567. In 1861 abolitionist George Livermore introduced a Boston reprint of a 1643 English Civil War “Soldier’s Pocket Bible,” known colloquially as Cromwell’s Soldiers’ Bible.

“Sixth Debate with Stephen A. Douglas, at Quincy, Illinois,” October 13, 1858, CW, 3:279.

Warren, Lincoln Lore 567. See supra note 6 and associated text.

Elinor Des Verney Sinnette, Arthur Alfonso Schomburg, Black Bibliophile & Collector: A Biography (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1989), 157.

Benjamin Franklin Morris, Memorial Record of the Nation’s Tribute to Abraham Lincoln, 1865 (Washington, D.C.: W. H. & O. H. Morrison, 1866), 6.

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase to Mrs. Abraham Lincoln, March 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln Papers, 1774–1948, Manuscript/Mixed Material, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/pin2204/.

Robert Todd Lincoln to A. Wakeman, Nov. 28, 1908, Robert Todd Lincoln Family Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, box II:8, folder 7.

Ervin Chapman, Latest Light on Abraham Lincoln and War-time Memories, 2 vols. (New York: F. H. Revell, 1917), 2: 291.

James Cornelius, curator, Lincoln Collection at Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, e-mail message to author, October 10, 2017.

Barton, Lincoln Bibles, 8. Barton took this account from Joshua Speed, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln and Notes on a Visit to California (Louisville, Ky.: John P. Morton, 1884), 32–33. Independent researcher John O’Brien email message to author, September 11, 2018.

The Charles W. Merrill Bible is 3.5 inches wide, 5.5 inches high, and 1.0 inch deep. Thanks to Jennifer Hornsby, research librarian, Peabody Essex Museum, email messages to author, August 9, 2018, and September 11, 2018.

This was less than two months before Robert Todd Lincoln wrote to Dennis Hanks regarding his inspection of the leaves of the Thomas Lincoln Bible family record.

Quarterly Journal of Current Acquisitions, May 1958, 197. Thanks to Clark Evans, a thirty-year veteran of the Rare Books and Special Collections reading room at the Library of Congress, for bringing this Bible to my attention.

Like the Mary Lincoln Bible, the Robert Turner Bible is large, approximately 9.75 inches wide, 11.5 inches high, and 3.5 inches deep.

When I asked Lincoln historian Douglas Wilson about Hanks’s claim, he responded: “Dennis Hanks is not a consistent informant nor does his testimony on things like his own role in AL’s early education inspire confidence.” Douglas Wilson, email message to author, July 4, 2018.

Laine Dunham, Hildene vice president and creative director, email message to author, August 5, 2018.

Amos S. King to Abraham Lincoln, March 4, 1861. Courtesy of the Lincoln Family Home at Hildene.

John G. Nicolay to Amos S. King, March 8, 1861. Courtesy of the Lincoln Family Home at Hildene.

Thanks to the following staff at Hildene for their assistance in the investigation of the Bible: Laine Dunham, vice president and creative director; Seth Bongartz, president; and Stephanie Moffett Hynds, programming director. Also, special thanks go to Catherine Sharkey, collections care specialist, for her invaluable help with the inspection of the Bible.

Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, or Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (New York: G. W. Carleton & Co., 1868), 118–19.

Lincoln’s friend Orville H. Browning recalled spending an afternoon with Lincoln in the White House Library when Lincoln “was reading the Bible a good deal,” in Michael Burlingame, Oral History of Abraham Lincoln (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996), 5; Captain James B. Mix, a commander of Lincoln’s bodyguard, said Lincoln, with his arm around Tad, “read the Bible each morning,” in Francis B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1874), 262; Captain David Derickson, another of Lincoln’s bodyguards, attests to the same thing as Captain Mix in Matthew Pinsker, Lincoln’s Sanctuary: Abraham Lincoln and the Soldiers’ Home (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 84; John G. Nicolay and John Hay talk about the president reaching “for the Bible which commonly lay on his desk” to look up a Scripture, in John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History (New York: Century Company, 1904), 9:40; Alexander Williamson, tutor for the Lincoln boys in the White House, said that “Mr. Lincoln very frequently studied the Bible with the aid of Cruden’s Concordance, which lay on his table,” in Samuel Trevena Jackson, Lincoln’s Use of the Bible (New York: Eaton & Mains, 1909), 8; Joshua Speed talks about finding Lincoln “intently reading his Bible” at the Soldiers’ Home in his Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, 32–33; presidential bodyguard William Henry Crook said “the daily life of Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln usually commenced at eight o’clock, and immediately upon dressing the President would go into the library, where he would sit in his favorite chair in the middle of the room and read a chapter or two of his Bible,” from Henry Rood, ed., Memories of the White House, the Home Life of our Presidents from Lincoln to Roosevelt, Being Personal Recollections of Colonel W. H. Crook, (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1911), 15. Noteworthy from these accounts is that Lincoln apparently kept a Bible on his office desk and one on a small table in the library.

Herndon’s Informants, 521. Carpenter talks about a Mr. John Jay, who saw Lincoln reading a “dogeared copy” of a pocket New Testament, see supra, note 59 and accompanying text; Holland, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, 237, writes about Newton Bateman, the superintendent of public instruction for the State of Illinois, who saw Lincoln draw “from his bosom a pocket New Testament.”

Most of the other Bibles known to have been in the White House (the Mary Lincoln Bible, the Fisk University Bible, the Robert Turner Bible, the Noyes Miner Bible) were too large and ornate for daily use. It is not known if the First Inaugural Bible was returned by clerk Carroll to the Lincoln family during the war years, and it is not known if the pocket-size Bible that Lincoln inscribed to Charles W. Merrill in May 1863 was read by Lincoln at all. Considering that the president sent it as a gift, he presumably would not have previously used it. As already mentioned, the Thomas Lincoln Bible was probably never in the White House.

For an account of Sojourner Truth’s visit with Lincoln in the White House and their discussion about the Freedmen’s Bible, see Sojourner Truth, Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a Bondswoman of Olden Time (Boston: privately published for the author, 1875), 176–79.

I have inspected all of the available Bibles that could be considered Lincoln’s “personal Bible” while in the White House: the Mary Lincoln Bible, the First Inaugural Bible, the Robert Turner Bible, and the Amos S. King Bible. None of these Bibles has markings at Isaiah 5:27 and 28, as B. F. Morris and the Salmon Chase letter to Mary Lincoln indicate they would, had they been used for the second inaugural. Neither do they have markings at Matthew 7:1, Mathew 18:7, or Revelation 16:7, which the April 6, 1945, Library of Congress letter stated might have been the Scripture the Second Inaugural Bible was open to. DeLisa M. Harris, Special Collections Librarian, kindly verified no markings in the Fisk University Bible, either. Email message to author, May 7, 2019. See supra, notes 67 and 68 and associated text.

RR Auction, https://www.rrauction.com/PastAuctionItem/3366472. The Bible is a King James version published in London by Eyre and Spottiswoode in 1852.

Robert Todd Lincoln to A. Wakeman, Nov. 28, 1908, loc. cit., note 71 and accompanying text.

Condition and Treatment Report, Sept. 21, 1998, Abraham Lincoln Birthplace NHS, NPS ABLI Archives and Museum Collection.

Ibid., 2, mentions that there is some writing, including Abraham Lincoln’s and Thomas Lincoln’s names, on the inside covers (“pastedowns”) of the Thomas Lincoln Bible.

A thorough inspection of the Thomas Lincoln Bible by experts for handwritten notes, dates, marks, or underlining might clear up whether Lincoln made use of this Bible in the White House.