Lincoln’s New Salem, Revisited

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The role of destiny is a thread that runs through the story of Abraham Lincoln’s life. The events, occurrences, and people he encountered consistently created situations perfectly suited to help Lincoln advance toward his ultimate destination. This thread is visible throughout his time in New Salem.

There is an almost mystical quality to the coincidence of Lincoln’s arrival and the ephemeral nature of the village’s existence. Founded in 1829, it seems to have been placed there for the coming of Lincoln two years later. At this point in his life he had no rudder; New Salem provided him direction, guidance, support, and the life training he lacked. When he left six years later, he had been transformed and prepared for the task that lay before him. The village disappeared a few years after his departure. William Herndon, Lincoln’s long-time law partner and first biographer, noted, “The people of New Salem had a good deal to do in forming Lincoln’s life.”[1] Lincoln displayed the importance of his years in New Salem in the campaign biography he wrote in 1860 for John L. Scripps.[2] More than one-fourth of its content related to that one-eighth of his life.[3]

The geographic area in which these events occurred is not limited to the confines of the village itself. It includes the neighboring environs as well, particularly the area known as Sand Ridge, about seven miles north of the village, which proves to have had a bigger part in the story than most authors have noted. The influence of the entire area’s residents is a significant portion of the total impact on Lincoln from his six years at New Salem. That area is bounded on the west by Cass County and on the east and north by the Sangamon River. There were a few tiny settlements within its boundaries: Oakford, Pen Hook, Atterbury, and the community formed around the Concord Cumberland Presbyterian Church and its Old Concord Cemetery.[4]

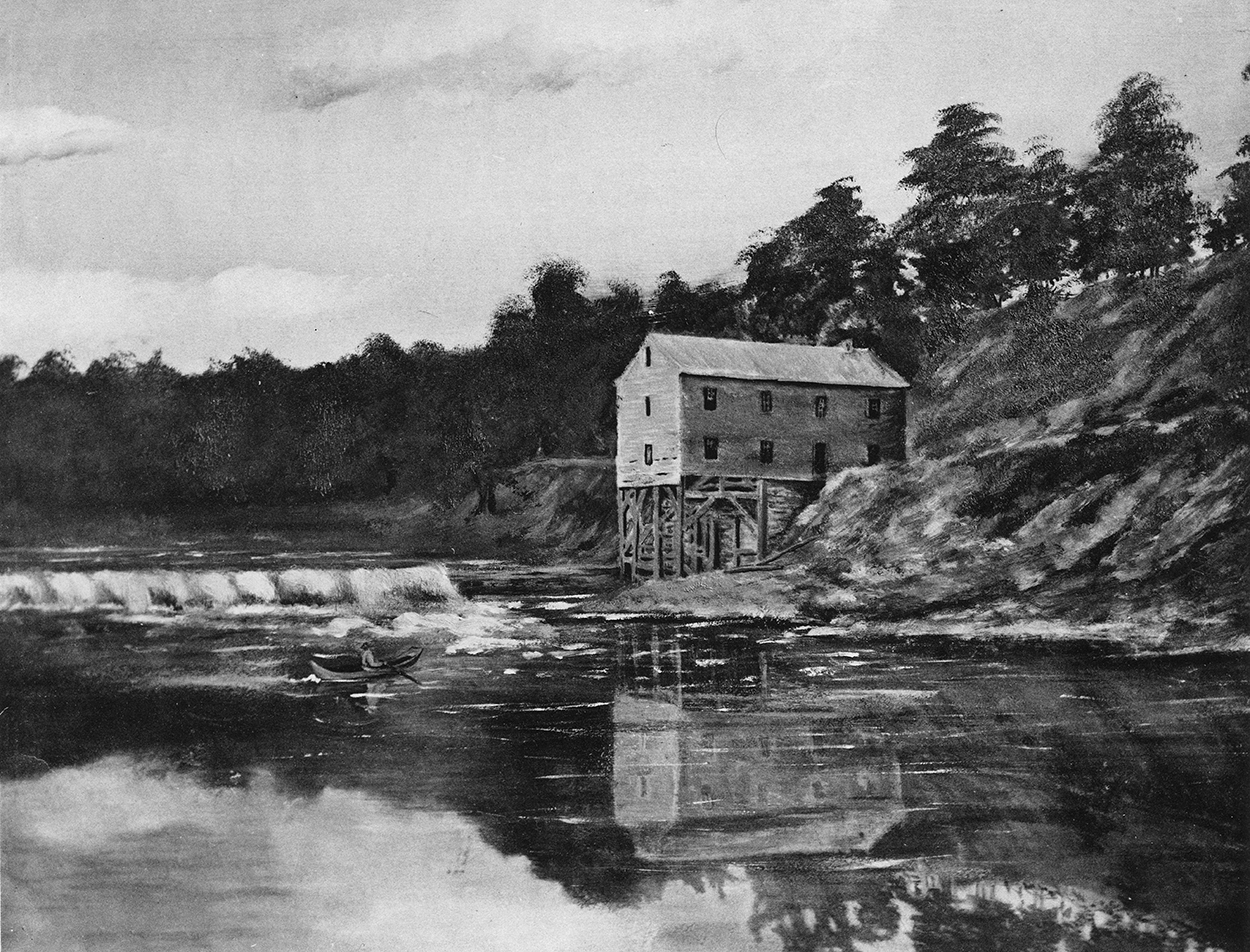

Figure 1. From a painting by “Mrs. Bennett” of the grist/saw mill built by James Rutledge and John Camron on the west bank of the Sangamon River in 1829, below the Village of New Salem on the bluffs above. The scene includes the mill dam that snared Lincoln’s flatboat in 1831, launching the chain of events described in this article. Source: Menard-Salem-Lincoln Souvenir Album (Petersburg, Ill.: Illinois Woman’s Columbian Club of Menard County, 1893).

Figure 1. From a painting by “Mrs. Bennett” of the grist/saw mill built by James Rutledge and John Camron on the west bank of the Sangamon River in 1829, below the Village of New Salem on the bluffs above. The scene includes the mill dam that snared Lincoln’s flatboat in 1831, launching the chain of events described in this article. Source: Menard-Salem-Lincoln Souvenir Album (Petersburg, Ill.: Illinois Woman’s Columbian Club of Menard County, 1893).The facts of New Salem’s founding are well settled. James Rutledge and his nephew, John Camron, natives of South Carolina and Georgia, respectively, picked the site on the west bank of the Sangamon River on which to build a gristmill and a sawmill, with homes on the bluff above. The two had previously purchased land in Sand Ridge in 1826 and 1828, with plans to dam Concord Creek and build the mill. These plans changed, and they chose the New Salem site, then in Sangamon County. First they recorded the site,[5] then constructed a dam and the two mills,[6] after which they surveyed and platted the town’s site. All of this took place in 1829.[7]

The survey divided the town into two parts. The original survey defined the east end of the town on the bluff, and the “Second Survey” the west end.[8] The current layout of Lincoln’s New Salem State Historic Site is confusing, because the parking lot and visitors center are at the west end, which was the back door of the original settlement. The location of the Rutledge Tavern on the original survey was at the intersection of two roads, the east-west road, now Main Street, that runs the length of the village, and the intersecting road coming up the hill, today a service road, which originally headed north and south from Springfield to Petersburg.

Like most such ventures, the new settlement was launched with optimism and hope, one of thousands of such pioneer gambles attempted as America moved west. Destiny, however, was at work from the beginning. New Salem’s temporal future was assured by the location, which was somewhat difficult to reach up on the bluff. In 1829 Samuel Hill and John McNamar built residences and a store in which a U.S. Post Office was established. Rutledge had become acquainted with McNamar, who, like Rutledge, had bought land in Sand Ridge, also in 1826 and 1828. Later in 1829, William Clary started a grocery on the bluff at the east end of the village. The term “grocery” meant that liquor was sold there by the drink. The building became the site where the rough Clary’s Grove “boys” would pass the time of day with wrestling, cock fights, gander pulls, and other frontier pastimes.

Gradual growth of the nascent town continued in 1830. Henry Onstot, a cooper, built a house and workshop on the east edge of the village near the bluff. This is not to be confused with the Onstot cabin and workshop near the entrance of the current village, to which he moved in 1835. In 1831 James Rutledge converted his home on the bluff to an inn. The growth of the community continued through 1831, 1832, and 1833.[9] Few new settlers took residence in New Salem after 1833.[10] In 1835 Samuel Hill built a large carding mill and wool storage house that added new vitality to the community. Estimates vary as to the ultimate size of the village: “some twenty-five buildings and more than a hundred inhabitants,” “some twenty-five families and twenty-five or thirty structures.”[11] Lincoln himself once said that the community “never had more than 300 people living in it.”[12] The surprising breadth of enterprises filled the basic needs of the residents. New Salem had four stores, one a “grocery,” an inn, a cooper, a cobbler, a hat maker, a furniture and wheel maker, two doctors, and a blacksmith, as well as the mills on the river. The bluff had an exposure of shale quarried by residents for their building foundations.[13] The village had a school and a schoolmaster, Mentor Graham. It was served by a stagecoach, beginning in 1834 and running from Springfield to Oquawka, on the Mississippi River. There was a licensed ferry across the Sangamon. New Salem was a commercial and social center for the surrounding region, drawing residents from all directions.[14]

Lincoln’s introduction to New Salem and its residents smacks of destiny. In March 1830, while the tiny settlement was in its early stages, Lincoln set out on the course that would intersect with New Salem. He was part of an entourage that migrated from southern Indiana to Macon County, Illinois. This group included his father, Thomas; his stepmother, Sarah Bush Lincoln; and her son, John D. Johnston. They had been persuaded to make this move by glowing reports about the opportunities in Illinois from John Hanks, a cousin of Lincoln’s deceased mother, Nancy. Lincoln, now twenty-one, had agreed to see his family through their first year in frontier Illinois, staying with them in a rough homestead cabin in Macon County. Coincidentally, it was also on the banks of the Sangamon River, approximately sixty miles east of New Salem. Their year at this site was difficult, even life-threatening, because of the winter of 1830–31, forever known as the “Winter of the Deep Snow.” Between the first of December and the middle of February, snow piled up three to four feet deep and drifted to even greater depths. The temperature fell below zero for extended periods, and day after day passed without sunshine. The harsh conditions obliterated the wild game, and food became scarce.[15]

When the winter was over, Lincoln had fulfilled his obligation to his family. John Hanks had negotiated an agreement with Springfield’s Denton Offut for a crew to float a flatboat loaded with farm products down the Sangamon to the Illinois, the Mississippi, and ultimately New Orleans. Hanks hired Lincoln and Johnston to fill out his crew. The snowmelt that year made it difficult to travel cross-country, so the crew paddled a canoe to Sangamo Town, which was downstream to the west on the Sangamon, about six miles from Springfield. At that time Sangamo Town was larger than New Salem, though it too no longer exists. The crew stayed there about a month while they built a flatboat eighty feet long and eighteen feet wide.[16] On April 18, having loaded their boat with pork, cornmeal, and live hogs, Offut, Johnston, Hanks, and Lincoln embarked. What happened the next day on this momentous journey not only assured the immortality of New Salem but arguably changed the history of the nation.

The river had fallen some since the peak of the snowmelt, and the large flatboat became stuck on the milldam at New Salem. The entire venture was at risk. Residents of the village gathered on the bluff to watch the impending disaster. Lincoln sprang into action as water poured into the rear of the boat. First, the cargo was moved to the prow, then temporarily off the boat. Second, Lincoln borrowed an auger from Onstot’s cooper shop on the bluff, drilled a hole in the bottom of the boat, and asked for volunteers to stand on the front of the boat, thus shifting the weight. He carved a plug from a tree limb to match the size of the hole. When the water drained, he inserted the plug and the boat was tipped over the dam and slid into the river below. The cargo was reloaded, and the flatboat continued to Beardstown and on to St. Louis, where Hanks left the venture. The others continued to New Orleans, where they stayed for about a month. Lincoln had made a similar trip in 1828 from Indiana, starting on the Ohio River. He had been engaged by a merchant named Gentry to accompany Gentry’s son on the voyage. That experience served him well for this second perilous trip. When Lincoln observed the horrors of the New Orleans slave trade on these occasions, it was a vision forever burned into his consciousness. The boatmen returned by foot and steamboat to Illinois by early July 1831.[17]

In the meantime, Offut decided to start a store in New Salem. Having observed Lincoln’s prowess and creativity, he hired him to clerk in the store. Offut had obtained a license to sell liquor in the store in July, about the time Lincoln returned from New Orleans and a visit, by foot, to his parents in Coles County, Illinois. Thus began the most important six years of Lincoln’s early life. He was embraced, almost adopted, by the tiny community; as he himself later wrote, “Here he rapidly made acquaintances and friends.”[18] He accepted the warm hospitality of the small village, which had eight or ten buildings at the time, with much of its growth still ahead. Just as New Salem provided for the needs of its residents, they in turn met the needs of this raw farmhand and boatman who landed in their midst. The settlement had no social structures or hierarchies, so all were evaluated on their own merits.

With a job working for Offut, Lincoln had arrived in time to vote in a local election on the first of August. He hung out at the polling place all day, immediately meeting most of the men in the precinct. His extraordinary physical assets, his willingness to work hard, and his renowned sense of humor made him immediately popular. As he himself wrote, “A. stopped indefinitely, and, for the first time, as it were by himself at New Salem.”[19] Lincoln helped Offut build the store, and he began to clerk on completion. The store gave him not only a job but a place to sleep. Offut hired Billy Greene to help Lincoln with his duties, not only running the store but also working at the mill. This close association created a friendship that lasted throughout Lincoln’s life. Now that he had a “room,” he soon made arrangements for board. Throughout his time in New Salem he boarded with a number of families, including those of John Camron, John McNamar, James Rutledge, Bowling Green, and Henry Onstot.

These arrangements provided Lincoln with meals at little cost and, more important, many close friendships. The village’s population offered an exceptional intellectual range and depth, as well as a variety of activities and informal organizations, all of which challenged and inspired Lincoln. Once in place at Offut’s store, Lincoln was, at the time, well suited to clerk at the highly visible enterprise. William Herndon later said of Lincoln, “His ambition was never satisfied; it was a consuming fire that smothered his finer feelings.”[20] Ambition shows in his early employments. The retail establishments gave him the opportunity to meet everyone in the hamlet and the surrounding vicinity. Ownership of the stores was fluid. In addition to Offut’s, McNamar’s, and Hill’s, there were two others. One belonged to Rowan and James Herndon, cousins of William Herndon who met Lincoln for the first time in New Salem. The Herndons started their store in 1831. That same year Reuben Radford also began operation of a store.

Acceleration of the settlement’s growth in 1831 included an eclectic mix of new people. This diversity was well suited for Lincoln’s development and broadening of his horizons. It is almost as if certain of them were hand-picked and placed there to help school him. Two doctors arrived in the village: the cultured Francis Regnier from Ohio, and John Allen, who had attended Dartmouth, from Vermont. A Presbyterian, he founded the local temperance society and Sunday school. James Rutledge had a library of thirty-five to forty books, which were no doubt available to Lincoln because of his time spent at the inn. Rutledge started a debating society in which Lincoln participated; his intellect displayed at its early meetings somewhat dismayed the other participants. George Warburton and Peter Lukins, who made shoes and other leather goods, also arrived about that time. Joshua Miller was a blacksmith whose brother-in-law, Jack Kelso, was something of a dreamer and loafer. Kelso exposed Lincoln to Shakespeare and Burns, whose work fueled Lincoln’s religious skepticism, as did Thomas Paine’s Common Sense and Age of Reason. The connection between New Salem and Illinois College in nearby Jacksonville speaks to the intellectual depth of the village. Its residents David Rutledge, James’s son; William Berry, one day to be Lincoln’s mercantile partner; and the Greene brothers, William G. and L. M., all attended the college, as did Harvey Ross, from Sand Ridge, who delivered mail to and from New Salem.[21]

Offut was less than a model citizen in many respects. For one, he was a loudmouth and braggart. When he touted the strength and athletic prowess of his new clerk, the toughs from Clary’s Grove got wind of it through John Clary, the Grove’s founder and the brother of New Salem’s grocery keeper, William. Jack Armstrong, the gang’s leader and the best wrestler and fighter in Clary’s Grove, challenged Lincoln to a wrestling match. This confrontation led to one of the most notable incidents in Lincoln’s early days in Illinois. He reluctantly accepted the challenge; the match was on. Offut and Clary bet ten dollars on their favorites, the first of many bets by the residents of the two communities, who turned out to see the contest held on the bluff. After sparring, the two men grappled and Lincoln seemed to be getting the better of it when Armstrong’s cronies joined in the fray. The enraged Lincoln offered to fight them all, one at a time. Armstrong intervened, and the two combatants called it a draw.[22] They shook hands, forming a friendship that lasted a lifetime. Thereafter Clary’s Grove was a pillar of political support for Lincoln. Given the frontier values of the community, the incident enhanced Lincoln’s stature throughout the area.

Within a year the Offut enterprise was fading away. When it ultimately closed, the deeply indebted Offut departed, never to be seen again. The now unemployed Lincoln decided to seek election to the state legislature in 1832 as a Whig, the party of government support of “internal improvements”: roads, levies, canals and other projects designed to spur economic growth of the young state. Lincoln announced his decision in a statement that appeared in the March 9 Sangamo Journal, the drafting of which was assisted by John McNamar and Mentor Graham. The announcement was prophetic: “Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say for one that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow man, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem.”[23]

Once again destiny intervened. In April of 1832, Black Hawk, a Sauk chief, and remnants of his band who had removed to Iowa by federal treaty, returned to Illinois. The chief brought four to five hundred horsemen, plus additional men and boys in charge of canoes, as well as women and children. The migration totaled approximately two thousand people. The frontier erupted in alarm, and Governor John Reynolds issued a call for volunteers. Lincoln was among the many from the vicinity who enlisted to fight in what became known as the Black Hawk War. With the support not only of the New Salem soldiers but also those from Clary’s Grove, Lincoln was overwhelmingly elected captain of this volunteer company. His election, Lincoln wrote in 1859, was “a success which gave me more pleasure than any I have had since.” He again expressed this sentiment six months later in his notes to John L. Scripps.[24]

He served throughout the brief war, first enlisting for thirty days and reenlisting for twenty days and then again for thirty more. In early July the hostilities ended. Lincoln saw no combat, but he later joked that he did bleed from mosquitoes. At Kellogg’s Grove, in northern Illinois, he helped bury seven men who had been killed in battle. Lincoln took full advantage of the opportunities that the service and militia offered. Given his hand-to-mouth existence then, three meals and his soldier’s pay were no small benefit. The opportunity to use his considerable networking skills was the more important benefit to him in the long run. The war drew many of the men who had come to the new state to establish their lives and fortunes. They included John J. Hardin, Joseph Gillespie, Edward Baker, and most important, John Todd Stuart, his future law partner and one of the primary relationships of his life. The enlistees also included John Calhoun and Thomas Neal, both of whom later hired Lincoln to work as a surveyor. He covered considerable geography, from the Mississippi at Yellow Banks, up and across the Rock River, and into Wisconsin, going as far north as the White River. At the end of the war his horse was stolen in Wisconsin, so he shared another’s horse, alternately riding and walking all the way back to Peoria. From there he canoed to Havana and then walked back to New Salem. He arrived in New Salem in mid-July and resumed his faltering campaign; his absence during most of it made election virtually impossible.[25] The vote, held in early August, showed Lincoln running eighth in a field of thirteen candidates, the top four of which were elected. He did, however, receive 277 of the 300 votes cast in the New Salem precinct. From this experience he was later to proudly state, “This was the only time A. was ever beaten on a direct vote of the people.”[26]

He later stated, “He was now without means and out of business, but anxious to remain with my friends who have treated me with so much generosity, especially as I had nowhere else to go.”[27] Comfortable in the village, he chose two occupations that he hoped would carry him to a better life. First was his purchase of a store. The other came later when he learned the art of surveying. These occupations offered more than a means to a living. The store was the social center of each village, where people gathered not only to shop but to socialize and become better acquainted. Surveying was vital to the development of the unsettled lands of central Illinois. It became more to Lincoln than a technical skill allowing him to earn a living. It put him in touch with entrepreneurs and key figures in the development and growth of Illinois. These associations stayed with him throughout his career.

Offut’s store failed in late 1832, or as Lincoln wrote, it “winked out.” The Herndon brothers were still operating their store, on the south side of Main Street. That fall, James sold his interest to William Berry. Rowan quickly lost patience with the unreliable Berry, so he sold his interest to Lincoln on credit. Reuben Radford had provoked the Clary’s Grove boys, who responded by trashing his store. Discouraged by this setback, Radford sold his stock to Berry and Lincoln in 1833, creating more debt. He also vacated his store across the road, a better location, so Berry and Lincoln moved there. As a team, the partners were ill-suited to run a mercantile establishment. Berry had a serious drinking problem that eventually killed him. Lincoln, on the other hand, was sometimes too busy reading and chatting with his visitors to devote time to their business. In April 1833 Lincoln sold out to Berry. This venture led him deeper into debt.

Lincoln’s prospects did not look good in the spring of 1833. He had no job and no apparent livelihood. He still had, however, his physical skills, charisma, bright mind, and persistence. On May 7 he was appointed U.S. postmaster for the village without ever seeking it.[28] This appointment came to Lincoln, a Whig, from the Democratic Jackson administration. It gave him a modest but steady income and several other advantages. He had access to all the newspapers that came through the post office, which was still in Hill’s store. It created regular contact with virtually all the settlers in the vicinity, a political asset as well. He held the position until the post office was moved to Petersburg in 1836.

In the fall of 1833 he was further rescued from the financial brink by John Calhoun, the county surveyor and a Democrat. On the recommendation of several New Salem residents, Calhoun appointed Lincoln as his assistant to work primarily in northern Sangamon County. Lincoln accepted after he was assured that his Whig affiliation would not be compromised by the appointment. He knew nothing of the craft, so he borrowed several textbooks from Calhoun, which he studied intensely for six weeks that fall. He acquired the necessary instruments, including a compass, a chain (the sixty-six-foot-long device used to measure distances), a staff, and several ten-foot poles. He borrowed a horse and acquired saddlebags. Probably the equipment was purchased with borrowed money, and he later purchased the horse.[29] In Sand Ridge plenty of work came to Lincoln, including the surveying of many roads, one of which is a well-improved road from Musick’s Ferry on Salt Creek to New Salem and west to the county line.[30] For real estate speculators, he surveyed several town sites, including that of Albany, a few miles west of present-day Lincoln, and New Boston, on the Mississippi near Yellow Banks, present-day Oquawka.[31] His last town survey was of Bath, which still exists, in November 1836.[32] He also surveyed many small tracts known as “timber tracts” for individuals as a wood fuel supply. They were usually in dense woods and required considerable surveying skill.[33]

Peter Lukins and George Warburton had left New Salem to found Petersburg in 1832. The town got its name after the two founders made a wager and played a card game to decide whose name the town would bear, either Georgetown or Petersburg.[34] Development lagged, so a real estate speculator, John Taylor of Springfield, acquired the site. He had already aided the growth of Springfield and developed his namesake town, Taylorville.[35] Taylor’s choice of Lincoln to perform a resurvey of Petersburg in 1836 was a measure of the latter’s stature as a surveyor. The importance of this experience cannot be overrated. It provided a desperately needed financial bridge between the poverty of his earlier enterprises and the law career, for legislative duty did not pay enough. Surveying brought him a wide range of invaluable associations and made him a participant in the growth and development of central Illinois. Knowledge of the intricacies of legal descriptions enhanced his real estate practice, an important part of his legal career.

The year 1834 was eventful for Lincoln. It marked the first stage of his emergence from the obscurity of rural New Salem and the beginning of the end of his time in the village. Early in the spring, at the urging of Bowling Green, a prominent resident of the area, Lincoln announced his candidacy for a second try at election to the Illinois General Assembly. This was a declaration of self-awareness of his increasing stature. Lincoln campaigned in the spring and summer, and, armed with his accomplishments and associations since his first race, he easily won the election. This time he ran second of the thirteen candidates, only fourteen votes behind the leader.[36]

His bright future, however, was clouded by his debt from the failed store operation. A creditor obtained a judgment against him and aggressively pursued collection by levying on his personal property, including his horse and surveying equipment. They were seized by the sheriff and sold at auction in November. Lincoln didn’t bother to attend the sale, but once again fortune smiled on him. A casual acquaintance from Sand Ridge, James “Uncle Jimmy” Short purchased the property at the auction for $120 and returned the items to Lincoln.[37] He was able to continue his surveying throughout the fall, and he repaid Short before he left for the legislative session. Two years older than Lincoln, Short had first met him in 1831 while visiting his sister in New Salem. They maintained a friendship that continued throughout Lincoln’s life. Lincoln repaid the kindness during his presidency: Short had moved to California and been wiped out by financial setbacks. Lincoln appointed him as the agent of an Indian reservation there at the handsome annual salary of $1,800.[38]

In November 1834 Lincoln went further in debt by borrowing $200 from Coleman Smoot, a local farmer and money lender. With the money Lincoln purchased a suit, paid some pressing debts, and had enough to cover the expenses for his first trip to the state capital in Vandalia. On November 28 he and five other members of the legislature from Sangamon County departed together. He was one of fifty-five members of the House. The session lasted until mid-February 1835, when he returned to New Salem.[39] Shortly before his return, William Berry died, “as a result of his dissipation, his too free access to the falling bowl.”[40] In addition to the personal loss, Berry’s death left Lincoln with the entire burden of the grocery debt the two had shared.

Lincoln’s primary goal was self-improvement and self-education. Conquering the complexities of grammar was at the top of that list, and the village provided the means. The area’s dedicated schoolmaster, with the unlikely name of Mentor Graham, was born in 1800 in Kentucky, where he had taught in several private schools for a number of years. He moved to the New Salem area in 1826 and settled on a forty-acre tract a quarter of a mile west of town. In 1829 he started a school on the edge of the village, where he educated many of the residents’ children.[41] He also tutored in their homes and was paid by the students’ parents. Lincoln set out to learn grammar and elocution from Graham, who also helped him in preparation for surveying.[42] Robert Rutledge said of Graham, “I know of my own knowledge that Mr. Graham contributed more to Mr. Lincoln’s education in New Salem, than any other man.”[43] Graham told Lincoln of a volume of Kirkham’s Grammar, a primer on the topic, owned by farmer John Vance, who lived six to eight miles from the village. Lincoln walked to Vance’s home and secured the textbook. All village residents related how intently he studied and struggled to understand the book’s challenges. When Billy Greene visited his old New Salem friend in the White House, Lincoln introduced him to William Seward as “the man who taught me grammar.” Greene was embarrassed by this description and replied that all he did was hold the book to check Lincoln’s endless recitation of its exercises. Lincoln told Greene that this was the only teaching of grammar he had experienced.[44]

Next Lincoln focused on the study of law. His friend from the Black Hawk War, John Todd Stuart, a Kentucky-born lawyer who was prominent in Springfield, had recommended the practice of law. Lincoln took this advice and acquired a copy of the basic law text of the day, Blackstone’s Commentaries. Two versions of the acquisition were told. In one, he purchased a copy of the Commentaries at an auction in Springfield after his election in 1834. In the other, he bought a barrel of miscellany for fifty cents while tending Offut’s store. At the bottom of the barrel was a copy of the Commentaries.[45] Either way, he had this invaluable text, which he devoured, forty pages at a sitting. Much of his reading was done at night by the light of the burning shavings in Onstot’s shop. He studied other standard texts borrowed from Stuart and his partner Henry Dummer, traveling to Springfield for this purpose, studying as he rode back and forth.

As Lincoln’s law studies progressed, he began to render rudimentary legal services to the village residents, although he was not yet admitted to practice. In 1833 he purchased a book of legal forms that aided him in preparing basic real estate documents, simple notes, and wills. He often appeared in uncomplicated, minor cases in the Justice of the Peace Court of Bowling Green.[46] Born in North Carolina in 1787, Green made his way to White County, Illinois, where he married Nancy Potter. They moved to the area of New Salem in 1819, first to Clary’s Grove and later to a forty-acre farm adjoining the village on the north. Lincoln became acquainted with the Greens shortly after his arrival, and the couple maintained a close relationship with him throughout his time in New Salem.[47] Green’s weight was 250 pounds, although he stood less than six feet tall. Nicknamed “Pot,” he was a jovial man, and he and Nancy were known for their generous hospitality. By 1831, when he was elected justice of the peace, he had become one of the best-liked and most influential members of the community. New Salem residents later labeled his role in Lincoln’s life as “almost a second father.”[48] Lincoln was a frequent visitor in the Greens’ home, where the men would hold long discussions about law and politics. In 1832 and 1833, Green lent Lincoln what few law books he had to further his studies. He was a continuing supporter and adviser to Lincoln in both law and politics. Although a Democrat, Green encouraged Lincoln to run for the legislature in 1834, in spite of the earlier loss.

When, in 1841, Green died at age fifty-four of a stroke, “Aunt Nancy,” as Lincoln came to call her, asked him to give the eulogy at Green’s funeral. He was unable, however, to complete his tribute to his friend, breaking down in tears and leaving the stand. At the conclusion of the service he escorted Aunt Nancy to a waiting carriage to see her home. On behalf of the Widow Green, Lincoln successfully sued Mentor Graham on a note Graham owed them.[49]

The story of Lincoln and New Salem would not be complete without discussion of the relationship between Lincoln and Ann Rutledge. Historians have disagreed about that subject since William Herndon included the story in a November 16, 1866, lecture on Lincoln in Springfield. He expanded the story in his famed biography Herndon’s Lincoln, finally published in 1889, after many false starts.[50] Ann Rutledge was the daughter of James and one of ten children. She was born in Kentucky on January 9, 1813, shortly before the family moved to Illinois, eventually settling in the New Salem area in 1829. Ann was courted there by John McNamar, who had assumed the surname McNeil when he moved west from New York to seek his fortune. He claimed he wanted anonymity so his family wouldn’t interfere with his business interests. Ann and McNamar became betrothed, but her family wanted her to wait to marry until she had matured more fully and had attended Jacksonville Female Academy for a year. Lincoln became closely acquainted with Ann and her family while boarding with them, as had McNamar. About the time Lincoln returned from the Black Hawk War, McNamar left New Salem, returning to the East allegedly to bring his family back. He was mysteriously gone for three years without explanation and only limited communication.

In 1833 the Rutledges moved to Sand Ridge, and most of Lincoln’s and Ann’s time together was spent there. McNamar’s absence gave Lincoln the opportunity to express his long-suppressed love for her. She reciprocated, and their relationship blossomed. They spent hours together, walking the woods and fields of the locale. They studied together, which included poring over Lincoln’s copy of Kirkham’s Grammar. In the summer of 1835 Ann was stricken with typhoid fever; before she died in late August, Lincoln visited her on her deathbed at her home. Like many of New Salem’s residents, her body was buried in Old Concord Cemetery, and Lincoln is said to have visited there frequently, even throwing himself on her grave during a heavy thunderstorm as if to protect her from the storm’s fury. Her father died later that year and was buried near her. All accounts of Lincoln’s overwhelming grief are consistent.[51] Lincoln’s neighbors worried about him until he regained his emotional equilibrium six months later. Nancy and Bowling Green, with whom he lived for six months, nurtured him through his dark depression.[52] Ann Rutledge’s tragic death is another instance in which destiny affected Lincoln’s path. Would his life have been different if their romance had ripened into marriage? Such is the description of their relationship running through Herndon’s talks and writings.

Some historians have disputed the whole story as charming fiction. The skepticism is summarized by Benjamin Thomas.[53] Among the most outspoken were Paul Angle,[54] James G. Randall and his wife, Ruth Painter Randall,[55] and Randall’s doctoral student David Herbert Donald. Donald later reversed his position in his Lincoln, published in 1995.[56] The most persuasive work supporting Abraham and Ann’s romantic relationship is that of Douglas L. Wilson, who compiled a scorecard of the recollections of New Salem residents gleaned from Herndon’s interviews.[57] A copy of Samuel Kirkham’s English Grammar (by then a standard primer for two decades) is an often overlooked, tangible piece of evidence of their relationship, bearing as it does an inscription that may be in Lincoln’s hand, “Ann M. Rutledge is now learning grammar.”[58] Others dispute the identity of the handwriting. Either way, there is little dispute that Lincoln gave this “treasured volume” of such importance to Ann, from whom it went through several generations of the Rutledge family before it came to repose in the Library of Congress.[59]

Several of Lincoln’s relationships after Ann’s death raise questions about the story. John McNamar returned to Sand Ridge shortly after Ann died. He took up residency in Petersburg, where he maintained a friendship with Lincoln. In late 1836 Lincoln wrote him from Vandalia about state business in which McNamar had an interest. Lincoln addressed him as “Dear Mack” and signed “Your friend.” In 1843 Lincoln wrote to him as Menard County assessor. He starts the letter “Friend McNamar.”[60] These letters hardly suggest that the two were rival suitors for Ann’s hand. Another such relationship is Lincoln’s involvement with Mary Owens, a less intense romance, that started within a year of Ann’s death. She was the charming, educated sister of Elizabeth Abel, wife of Bennett, both friends of Lincoln in New Salem. Abraham met Mary when she visited in 1833. A closer relationship took hold on her return visit in 1836. The couple seemed slowly moving toward marriage. The well-documented courtship reveals a tentative and uncertain Lincoln.[61] He wrote her a rather tepid letter in December 1836, after her return to Kentucky. Five months later, shortly after his move to Springfield, he sent an odd invitation to her to come to Springfield, the tone of which discouraged her from doing so. She took this advice, ending the relationship.[62] Lincoln’s unkind description of her and the courtship to his friend, Eliza Browning, of Quincy, wife of Orville Browning, shows an unfamiliar Lincoln.[63] Shortly after Lincoln’s death, Herndon interviewed the long since married Mary Owens Vineyard. Her remarks described a boorish, rude, and wavering individual.[64]

Lincoln closed the year 1835 attending the legislative session in Vandalia, which lasted into January 1836, when he returned to New Salem. From this point, the pace of his transition from rural resident to state leader accelerated. Upon his return, he continued his duties as postmaster until the post office was closed on May 30, 1836. He found time to continue his surveying, including a survey of Petersburg in February and his last town survey in Bath, beginning on November 1 and ending on November 16. In mid-March, he announced his candidacy for reelection to the legislature and was busy campaigning until the polling on August 6, in which he received the most votes of any of the seventeen candidates.[65]

On September 9, 1836, Lincoln was licensed to practice law by two justices of the Illinois Supreme Court, and on the following March 1, his name was entered on attorney rolls by the clerk of that court.[66] These momentous events represented the culmination of his diligent study in New Salem, without the usual apprenticeship. In 1860 he proudly declared, “He studied with nobody.”[67] He traveled to Vandalia for the opening session of the legislature on December 5, 1836. His resounding victory established his leadership of the Whig minority in the House. The Sangamon County delegation was known as the “Long Nine,” because all of them stood six feet or more in height. He played a major role in the relocation of the state capital from Vandalia to Springfield. This is vintage Lincoln, creating opportunity for both himself and his constituency by moving the seat of government to the city in which he intended to spend his political, professional, and personal life. On the fourth ballot, Springfield prevailed.[68] The session ended on March 6, and he traveled to Springfield to commence the practice of law. In April he returned to the village that had molded him to collect what few belongings he had. Legend has it that he made a final visit to Old Concord Cemetery and the grave of Ann Rutledge.[69] On April 12, 1837, a notice ran in the Sangamo Journal: “Stuart and Lincoln, Attorneys and Counselors at Law, will practice conjointly in the Courts of this Judicial Circuit.”[70] On April 13, 1837, Lincoln left New Salem, on a horse borrowed from Bowling Green.[71] He arrived in Springfield, prepared by the tiny rural village for all that lay ahead.

Lincoln’s departure from New Salem was part of a steady exodus, as one by one the families of the village moved away during the late 1830s. The growth of neighboring Petersburg sealed the village’s fate. In 1839 Lincoln shepherded a bill through the legislature carving up Sangamon County, such that portions of it created three new counties: Menard, Dane (now Christian), and Logan.[72] Ironically, Lincoln’s success in creating Menard, and the designation of Petersburg as its seat, was the final blow to New Salem. Jacob Bale acquired the entire site, and by 1840 the village no longer existed.[73] Four structures are known to have been moved to Petersburg, and several others may also have been moved there. Buildings that remained at the abandoned site slowly eroded away, erased by the elements over the balance of the nineteenth century, leaving open fields and encroaching woods. An exception was the Rutledge Tavern, which was the first building and also the last. Jacob Bale occupied it as a home into the 1870s; it collapsed around 1880.[74] The village was gone, but Lincoln’s friendships and their impact on him remained throughout his life. He represented many of the residents in his law practice over the years, and they were a steady source of political support.[75]

The village of New Salem had fulfilled its purpose. The place and its people had transformed the callow youth, whose flatboat had become stranded on the milldam, into the lawyer-politician who would one day save America.

Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, eds., Herndon on Lincoln: Letters (Urbana: Knox College Lincoln Studies Center and University of Illinois Press, 2016), 256.

Roy P. Basler et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (Springfield: Abraham Lincoln Association / New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953); 4:60–67, New Salem at 63–65.

Ronald C. White Jr., A. Lincoln: A Biography (New York: Random House, 2009), 44.

Raymond H. Montgomery, Living in the Shadows of Greatness (Petersburg, Ill.: self-published, 2006), 21–35.

Thomas P. Reep, Lincoln at New Salem (Petersburg, Ill.: Old Salem Lincoln League, 1927), 7–17.

Thomas P. Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 7–17; Benjamin P. Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem (Springfield, Ill.: Abraham Lincoln Association, 1934), 7.

The best sources for this brief history of the development of the village are Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, and Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem.

Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 17; Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 24.

AL to Isham Reavis, November 5, 1855, in Basler, Collected Works, 2:327.

Guy C. Fraker, Lincoln’s Ladder to the Presidency: The Eighth Judicial Circuit (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2012), 12–14.

John Hanks to William H. Herndon, June 13, 1865, in Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, eds., Herndon’s Informants (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 43.

Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 18–19; Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 59–60.

“Autobiography Written for John L. Scripps,” in Basler, Collected Works, 4:64.

Wilson and Davis, Herndon on Lincoln: Letters, 130. Herndon made this observation repeatedly in his talks and writings.

Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 24–26; Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 64–67.

Albert J. Beveridge, Abraham Lincoln, 1809–1858, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1928), 1:115, 116; “Communication to the People of Sangamo County,” March 9, 1832, in Basler, Collected Works, 1:8.

“To Jesse Fell, Enclosing Autobiography,” December 20, 1859, in Basler, Collected Works, 3:512; “Autobiography Written for John L. Scripps,” 4:64.

Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 33–43; Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 77–81.

Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 59; William E. Baringer, with Earl Schenck Miers, eds., Lincoln Day by Day: A Chronology (Dayton, Ohio: Morningside, 1991), 29; “Autobiography Written for John L. Scripps,” 4:64; “To Jesse Fell, Enclosing Autobiography,” 3:512.

Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 44–47; Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 89–93.

Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 94–100; Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 57–60.

Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 61–63; Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 101–104; a portion of this road survey appears in Basler, ed., Collected Works, 1: facing 24.

Lincoln’s plats of Huron and Albany appear in Basler, Collected Works, 1: between 48 and 49.

Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 111; Basler, ed., Collected Works, “Speech at Bath, Illinois, August 16, 1858,” 2:543. Lincoln spoke there while campaigning against Stephen A. Douglas; he reminisced about his history with the town, including platting it, calling it “then a wooded wilderness.”

Fraker, Lincoln’s Ladder to the Presidency, 130; Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 53.

Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 110; Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 65.

Wilson and Davis, eds., Herndon’s Informants, Robert Rutledge to WHH, November 18, 1866, 402.

Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 30, 31; Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 48.

Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 116; Ida M. Tarbell, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, 4 vols. (New York: Lincoln History Society, 1900), 1:93, 94, as told by Lincoln to an artist painting him in 1860.

Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, 2 vols. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 1:56.

Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney Davis, eds., Herndon’s Lincoln, by William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik (Urbana: Knox College Lincoln Studies Center and University of Illinois Press, 2006), xxii, 89–96.

Montgomery, Living in the Shadows of Greatness, 9–15; Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 75–79; Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 121–25.

Paul Angle, ed., The Lincoln Reader (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1947), 113.

J. G. Randall, Lincoln the President, Springfield to Gettysburg, 2 vols. (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1945). As an appendix, Randall inserted an essay, unrelated to the subject matter of his presidential history, titled “Sifting the Ann Rutledge Evidence,” 321–42. It attempts to refute tales of any romantic relationship between the two. Ruth Painter Randall was a strong advocate of Mary Lincoln, having published Mary Lincoln, Biography of a Marriage (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1953).

David Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948), 185–87; David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), 55–57. The reversal is explained in a lengthy footnote, 608–9.

Photographs of Kirkham’s Grammar can be seen in two books: Tarbell, Life of Abraham Lincoln, 1: facing p. 64; Joseph M. DiCola, New Salem: A History of Lincoln’s Alma Mater (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2017), 56.

Report from the Librarian of Congress for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1932 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1932), 17–19; Douglas L. Wilson, Honor’s Voice: The Transformation of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), 61.

AL to John McNamar, December 24, 1836, and November 9, 1843, in Basler, Collected Works, 1:60, 1:330.

AL to Mary S. Owens, Vandalia, December 13, 1836, in Basler, Collected Works, 1:54–55; May 7, 1837, Springfield, 1:78–79; Springfield, August 16, 1837, 1:94–95.

AL to Eliza Browning, April 1, 1838, in Basler, Collected Works, 1:117–19.

Douglas L. Wilson, Lincoln before Washington: New Perspectives on the Illinois Years (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997). See the index for entries of interviews by Herndon under the married name of Mary Owens Vineyard.

“Autobiography Written for John L. Scripps,” in Basler, Collected Works, 4:65.

Paul Simon, Lincoln’s Preparation for Greatness: The Illinois Legislative Years (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971), 76–105.

Thomas, Lincoln’s New Salem, 133; Reep, Lincoln at New Salem, 125.

New Salem: A Memorial to Abraham Lincoln; Official Catalogue (Springfield: Department of Public Works and Buildings, 1938). This fourth edition (the much shorter first edition having appeared in 1933, and a fifth edition, in 1940) reviews the 1937 status of each of the original buildings with a history of that building. The entry for the Rutledge Tavern is on p. 114.