Herndon’s “Auction List” and Lincoln’s Interest in Science

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: Copyright © Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. For permission to reuse journal material, please contact the University of Illinois Press ([email protected]). Permission to reproduce and distribute journal material for academic courses and/or coursepacks may be obtained from the Copyright Clearance Center (www.copyright.com).

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In 1844 thirty-five-year-old Abraham Lincoln asked William H. Herndon, who was nine years younger, to become his law partner. “Billy” was the son of an old friend, had boarded above Joshua Speed’s store at the same time as Lincoln, and was a bright young man, though he had left Illinois College without a degree before deciding to take up the law and becoming a clerk in the office of Logan & Lincoln. Contemporaries and later historians have proposed numerous explanations for why Lincoln chose someone so young and inexperienced to be his law partner. There are many plausible explanations, not all of which can be correct, and probably more than one factor contributed to Lincoln’s decision. In his classic study of Lincoln’s legal career, John J. Duff concluded that “weighing the few possible advantages against the many distinct disadvantages involved in entering into a partnership with Herndon, it is not clear on any rational ground why Lincoln . . . should have made the choice he did.”[1] In the half century since Duff’s verdict, no consensus has emerged among scholars.[2] Speculation about Lincoln’s motivation caused Herndon himself in later life to declare emphatically: “I don’t know and no one else does.”[3]

To the numerous attempts to explain Lincoln’s choice one might add a new one relating to his own intellectual development. Lincoln did not need Herndon for technical legal information or as a confidant, for Lincoln was not in the habit of speculating out loud with anyone. Yet Herndon could be useful to Lincoln in a particular way because one of Herndon’s peculiarities was that, even more than Lincoln, he was mad about reading, especially scientific works. At college Herndon “acquired an unmanageable appetite for books.” An exuberant Springfield bookseller reportedly said that “Mr. Herndon,” in the 1850s, read every year more new books in history, pedagogy, medicine, theology, and general literature, than all the teachers, doctors, and ministers in Springfield put together.”[4] In 1866 an eastern journalist deemed Herndon’s one of the best private libraries in the West.[5] A portion of that library—a thousand books—was put up for auction by an impoverished Herndon in 1873.[6] However, he still possessed enough books in 1879 to fill the walls of a 16-by-16-foot-square room.[7] Many of whatever books Herndon and Lincoln separately owned were, after 1844, adorning the shelves and tables of the office of Lincoln & Herndon, and many more were added over the next seventeen years before Lincoln’s final departure for Washington. “I had an excellent private library,” Herndon later recalled, “probably the best in the city for admired books. To this library Mr. Lincoln had, as a matter of course, full and free access at all times.”[8]

For such an avid reader as Lincoln, this ready access must have assisted his unending program of self-education, but one cannot be a great deal more specific than that.[9] Robert C. Bray, in his article “What Abraham Lincoln Read,” evaluated the likelihood that Lincoln actually read any of the various works that acquaintances and scholars have over the years suggested he might have read, and, although Bray did not directly consider Herndon’s auction list, many of the books he discussed also appear on that list, which must have included some books that had actually been owned by Lincoln.[10] In later years (1870 and 1874) Mary Todd Lincoln wrote to friends that Herndon had “appropriated” the “family library” and had stolen “my husband’s law books & our own private library.”[11] Most of the books on the auction list might have had an appeal for both men, but some were published only after Lincoln left Springfield, while others seem unlikely choices for Herndon to have purchased for himself. While both men no doubt owned books that they simply kept at their respective homes—Herndon more so than Lincoln—the bookcases and tables in their law office were filled with a great deal more than legal texts. In 1867 a journalist from Cincinnati visited Herndon in the office and noted that two bookcases did contain law books, but a third contained forty-five books—whose titles he recorded—which were an eclectic mix on everything except law.[12] Probably new titles appeared in the office and disappeared at the partners’ whim.[13] William E. Barton wrote that he possessed “several volumes” once owned by Lincoln that “bear the name of Lincoln and Herndon in his writing.”[14]

Herndon did more than merely buy books and make them available to Lincoln. A contemporary wrote that at the end of the working day Lincoln would remark, “Billy, what book have you worth while to take home tonight?” Another source related that Lincoln “would stretch himself on the office cot, aweary of his toil, and say, ‘Now, Billy, tell me about the books’; and Herndon would discourse by the hour, ranging over history, literature, philosophy, and science.”[15]

In his later biography of Lincoln, and elsewhere, Herndon was haughty and even contradictory about Lincoln’s reading habits, writing with some exaggeration that Lincoln “read less and thought more than any man in his sphere in America. No man can put his finger on any great book written in the last or present century that he read thoroughly” and that Lincoln “often quoted” the Bible and Shakespeare but “never read either one through.”[16] After mentioning a few works on slavery that both he and Lincoln read, Herndon added, “After reading them we would discuss the questions they touched upon and the idea they suggested, from our different points of view. I was never conscious of having made much of an impression on Mr. Lincoln, nor do I believe I ever changed his views.”[17]

That remark, however, may concern only issues relating to slavery, on which Herndon was always more radical than Lincoln. On other subjects Lincoln probably enjoyed Herndon’s efforts to act as a mentor. While serving in Congress in 1848 Lincoln wrote Herndon a letter containing paternalistic advice on various matters, but he sweetened the pill by adding: “You have been a laborious, studious young man. You are far better informed on almost all subjects than I have been.”[18] While in Washington, Lincoln was a noted “book-worm”[19] in the Library of Congress, and after returning to Springfield he seemed to thirst for knowledge with new zeal. Herndon wrote specifically that “Lincoln from 1849 to 1855 became a hard student and read much, studied Euclid and some mathematical books, read much in the political world.”[20] The scattered evidence of Lincoln’s research during this period suggests that little of it was literary, most was political, and a great deal was scientific. If he so wished, Herndon could have talked for hours about natural science. According to his biographer, David Herbert Donald, Herndon took his children for carriage rides into the countryside every Sunday “to teach them botany, geology, and ornithology.” One nephew never “saw a botany book that knew more about plants.”[21]

Two scientific works appearing in the auction list—The Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation and The Annual of Science—were specifically mentioned elsewhere by Herndon as greatly interesting Lincoln. Eventually both men owned a copy of The Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, which was first published anonymously in London in 1844 by Edinburgh writer and publisher Robert Chambers. Obviously influenced by Charles Lyell and many other scientific writers, Chambers rejected “special creations” and instead argued for a progressive “development” that involved not only plants and animals but also geology (cutting across Lyell’s view) and, indeed, the entire cosmos. No area escaped Chambers’s analysis, from astronomy to zoology, and he included mankind as developing according to “natural laws” originally laid down by the Creator. Chambers was a good writer whose cheerful and elegant explanations of the latest arcane research made The Vestiges a publishing phenomenon. Herndon seems to have owned an 1853 octavo edition, but the auction list also mentions a smaller, undated octodecimo edition.[22] The latter may be the book which, according to Herndon’s two slightly differing accounts, was either given or loaned to Lincoln by his friend, a Springfield tailor, James W. Keyes. The Vestiges “interested him so much that he read it through,” Herndon wrote. The book’s “doctrine of development or evolution . . . interested him greatly, and he was deeply impressed with the notion of the so-called ‘universal law’—evolution.” (The term evolution was probably not yet in common usage back when Herndon and Lincoln might have actually discussed “development.”) According to Herndon, after reading the book, Lincoln “did not extend greatly his researches,” although he “subsequently read the sixth edition of this work, which I loaned him.” Herndon believed that “by continued thinking in a single channel [Lincoln] seemed to grow into a warm advocate of the new doctrine.” According to Herndon, this was Lincoln’s only “investigation into the realm of philosophy. . . . ‘There are no accidents,’ he said one day, ‘in my philosophy.’”[23]

Regarding The Vestiges’s possible influence on Lincoln, Herndon later wrote: “Mr. Lincoln had always denied special creation, but from his want of education he did not know just what to believe. He adopted the progressive and development theory as taught more or less directly in that work. He despised speculation, especially in the metaphysical world. He was purely a practical man. . . . He held that reason drew her references as to law, etc., from observations, experience and reflection on the facts and phenomena of Nature. . . . He was a materialist in his philosophy.”[24]

Herndon mentioned in some detail Lincoln’s regard for another scientific work, an annual journal: “Sometime about 1855 I went into a bookshop in this city and saw a book, a small one, entitled, called, [sic] I think, The Annual of Science. I looked over it casually and liked it and bought it. I took the book to Lincoln and H.’s Office. Lincoln was in, reading a newspaper of value; he said me: ‘Well, Billy, you have got a new book, which is good, I suppose. What is it? Let me see it.’ He took the book in his hand, looked over the pages, read the title, introductions, and probably the first chapter, and saw at a glance the purpose and object of the book, which were as follows: to record, teach, and fully explain the failures and successes of experiments of all philosophies and scientists, everywhere, including chemistry, mechanics, etc. He instantly rose up and said that he must buy the whole set, started out and got them. On returning to the office he said: ‘I have wanted such a book for years because I sometimes make experiments and have thoughts about the physical world that I do not know to be true or false. I may, by this book, correct my errors and save time and expense.’”[25] The Annual of Scientific Discovery: or, Year Book of Facts in Science and Art, exhibiting the most important Discoveries and Improvements in Mechanics, Astronomy, Geology, Zoology was edited from 1850 to 1866 by David Ames Wells, a former student of Harvard naturalist Louis Agassiz. In 1865 Wells was appointed chairman of the National Revenue Commission by Lincoln.[26]

At times Herndon expressed some dismay at Lincoln’s lack of interest in more theoretical works. For several years, by his own account, Herndon “subscribed for and kept on our office table the Westminster and Edinburgh Review and a number of other English periodicals,” and he was clearly influenced by the book reviews he read in these publications. Herndon added that he “purchased the works of Spencer, Darwin, and the utterances of other English scientists, all of which I devoured with great relish. I endeavored, but had little success in inducing Lincoln to read them.”[27] “I imported books from London, through the house of C. S. Francis & Co [of New York]. When I heard of a good work, I ordered it, English, French, or German, if the two latter were translated. I kept many of my books in my office, especially the new ones, and read them. Mr. Lincoln had access to all such books as I had and frequently read parts of the volumes, such as struck his fancy.”[28] “Occasionally [Lincoln] would snatch one up and peruse it for a little while, but he soon threw it down with the suggestion that it was entirely too heavy for an ordinary mind to digest.”[29]

When Herndon was researching for his biography of Lincoln, the types of questions that Herndon evidently put to various associates of Lincoln give the impression that Herndon was puzzled by Lincoln’s greater interest in hard science than in more speculative works. According to Herndon’s notes, David Davis responded to his queries by saying that Lincoln read “no histories, novels, biographies,” but that “his mind struggled to arrive at moral & physical-mathematical demonstration . . . had a good mechanical mind and knowledge . . . studied Euclid . . . the exact sciences.”[30] When Herndon asked one of Lincoln’s closest acquaintances “whether Mr. Lincoln was given to abstract speculation,” Joseph Gillespie replied: “He wanted something solid to rest upon, hence his bias for mathematics and physical sciences.” Gillespie recounted Lincoln’s theorizing—“even before he had read the philosophical explanation”—that a musket ball fired horizontally and one dropped vertically would hit the ground at the same time.[31]

Herndon’s auction list contained dozens of works on natural science that may or may not have interested Lincoln, but those most likely to have appealed to Lincoln probably related to inventions. Of course, Lincoln himself obtained a U.S. patent in 1849 for his invention of a device to help river vessels avoid or escape being grounded.[32] The auction list included such works as John Beckman’s History of Inventions, Discoveries and Origins (two volumes, 1846), a History of Wonderful Inventions (1849), and the Rev. J. Blakely’s Theology of Inventions (1856), as well as ten non-consecutive volumes of the Patent Office Reports (beginning in 1847, with none dating after Lincoln’s departure from Springfield in 1861).[33] Lincoln’s interest was so great that the single lecture that he ever produced was about “Discoveries and Inventions.”[34] Herndon was not impressed. As his law partner sat in the office whittling on a model to be submitted with his application for a patent, Herndon soon tired of hearing about the invention’s “merits and the revolution it was destined to work in steamboat navigation,” and a decade later, in Herndon’s view, Lincoln proved he was as bad at lecturing about inventions as he was at making them.[35]

One of the natural sciences about which Herndon was knowledgeable and which apparently interested Lincoln as well was geology. In 1867, when providing a technical summary of regional geology to a journalist visiting from New England, Herndon declared, “We had no need of Agassiz out here to tell us what things meant.”[36] And six years later, when he auctioned part of his library, the advertisement included such recent works on geology and related topics as David T. Ansted’s The Great Stone Book of Nature (1851), W. R. Johnson’s On the Use of Anthracite in the Manufacture of Iron (1841), Sir Charles Lyell’s Manual of Elementary Geology (probably the New York version of the 6th edition, 1857), Hugh Miller’s Footprints of the Creator (1849) and Popular Geology (1859), Robert Dale Owen’s Key to the Geology of the Globe (1857), David Page’s Introductory Text-Book of Geology (perhaps the 1854 edition), Julius A. Stockhardt’s Chemistry of Agriculture (1855), Adam Vulliet’s Geography of Nature; or the World as It Is (1856), and Edward Hitchcock’s Religion of Geology and Its Connected Sciences (1851). Whether Lincoln owned or read any of these books is unknown, but we do know that another book by Hitchcock, Religious Truth Illustrated from Science (1856), is also on the list, and a copy of it is preserved in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, inscribed on the flyleaf “WHH to A. Lincoln.”[37]

It appears, however, that after Lincoln’s death Herndon remained curious about the extent of Lincoln’s interest in geology. Joseph Gillespie responded to Herndon’s inquiries by asserting that Lincoln “was fond of astronomy but I can’t call to mind any reference of his to geology. He doubtless had read and thought of the subject, but it did not engage his attention to the degree that astronomy and mechanical science did.”[38] From his numerous interviews with Lincoln’s former law partner, John T. Stuart, Herndon heard about some subjects that Lincoln pursued and some he avoided, but there was no mention of geology.[39] However, Stuart had told a different interviewer back in 1860 that “I consider [Lincoln] a man of very general and varied Knowledge—Has made Geology and other Sciences especial Study.”[40]

Herndon’s Life of Lincoln included in a footnote a story about a journalist, John S. Bliss, who visited Lincoln at home in 1860. Bliss picked up a shell from a parlor shelf and said he thought it would be “called a Trocus by the geologist or naturalist,” and, according to the biography, “Mr. Lincoln paused a moment as if reflecting and then replied, ‘I do not know, for I never studied either geology or natural history’.”[41] However, Bliss’s original letter to Herndon, written in 1867, had expressed it more simply: “I . . . said, ‘This I suppose, is called a Trocus by the geologist or naturalist.’ Mr. Lincoln replied, ‘I do not Know for I never studied it.’”[42] If these were Lincoln’s words, then “it” more likely referred to the particular shell (about which he knew less than the journalist) than to some general admission that he had “never studied either geology or natural history.” If the elaboration was written by Herndon’s coauthor, Jesse W. Weik, then Herndon either missed it or accepted it, and it may simply reflect Herndon’s view that Lincoln never demonstrated the more systematic interest in geology and natural history that Herndon possessed. Probably the trocus was just a bit of decoration arranged by Mrs. Lincoln, along with abalone shells attested elsewhere.[43]

If Lincoln had ever felt curious about the trocus, he always could have asked Herndon about it or, better still, one of his friends who were professional geologists. The state’s geological collection was first located in the Supreme Court Room of the Capitol about 1855, then, over the winter of 1855–56, in the Senate chamber, later in unheated rooms in the newly built State Arsenal, and then for several years in the Masonic Hall on the northeast corner of Fifth and Monroe Streets—just around the corner from the Lincoln & Herndon law offices. After November 1859 Lincoln could have walked north on Eighth Street to a house four doors away from his own to chat with Amos Worthen, who was the state geologist from 1858 to 1887.[44]

Lincoln had represented Worthen in a debt-collection suit in 1841 when the geologist was still running a dry-goods store in Warsaw, Illinois, and Lincoln might have learned then, or later when they were neighbors, that Worthen was a free-thinker. Yet any friendship between them may have been strained later when Lincoln apparently gave some support to another member of the Illinois Geological Survey, Joseph Henry McChesney, who, though officially an assistant geologist, was more a rival than a colleague of Worthen.[45] McChesney was born in Ohio in 1824 but by the age of twenty was resident in Illinois. He studied at Oberlin College in 1846–48, Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, in 1852, and Andover Theological Seminary in 1852–55, before working as a teacher in Millersburg and later in Springfield.[46] McChesney had become an assistant at the Illinois Geological Survey sometime before 1857, when Lincoln’s close friend, Orville H. Browning, recorded in his diary that he spent an afternoon “with Dr. McChesney among his minerals and fossils” in Springfield, and probably Lincoln had also met the young geologist by that time.[47] Early in 1858, when Worthen’s predecessor was to be replaced, both Worthen and McChesney sought the position. Although McChesney failed to get the appointment, friends in the legislature pressured Worthen into signing some agreement with McChesney regarding geographical areas of responsibility for the geological survey. McChesney later accused Worthen of violating the agreement, and a bill was introduced in the legislature to support McChesney’s position. Lincoln is said to have tried unsuccessfully to intervene with Governor Bissell in a way that might have served McChesney’s interest.[48] A few months later Lincoln received a letter from another geologist, Richard P. Stevens in New York City, apparently an old Republican acquaintance from Danville, Illinois. “I see our friend McChesney has taken the Northern part of your state as his appropriate field. It is sincerely to be wished that the new head of your survey [Worthen] will give the State a good report and contribute to popularize the Science of Geology among the people.”[49] Stevens, like McChesney, eventually published a string of new fossil discoveries, and McChesney’s fossil collection was coveted by America’s foremost geologist, James Hall of the New York Geological Survey.[50] McChesney was an early member of the Illinois Natural History Society, which began in 1858, and by 1860 he was working to establish an Agricultural College at the University of Chicago, where he had been offered a professorship.[51] During the 1860 presidential election McChesney campaigned for Lincoln and later benefited from his friendship with the president, who in 1862 effectively gave McChesney a grand opportunity to study in Europe by appointing him U.S. Consul in Newcastle upon Tyne.[52] McChesney spent perhaps too much time on geological jaunts, for Secretary of State William H. Seward complained that the consul was insufficiently zealous in reporting on ship-building and supply activities connected with Confederate blockade-running.[53] In January 1865, shortly after Lincoln’s re-election, McChesney wrote from England to Lincoln’s secretary John G. Nicolay—apparently an old friend—and mentioned that he was “collecting materials to have a beautiful chess board made for Mr. Lincoln of precious stones; each of the light spots will be of a different variety of stone.”[54] This was a perfect gift from a geologist to someone interested in geology, especially if McChesney had some personal experience of playing chess with Lincoln or with Nicolay, both of whom, according to Lincoln’s son, Robert Todd Lincoln, “played a good game of chess . . . and played many games in the [State] Library in times of leisure.”[55]

In addition to knowing some geologists personally and having access to Herndon’s volumes on geology, Lincoln may well have educated himself on the subject by reading elsewhere. Allen C. Guelzo suggests that Lincoln probably read Lyell’s Principles of Geology, which first appeared in 1830, but there is no specific evidence for this. Herndon’s auction list mentions only Lyell’s Manual of Elementary Geology in an edition that probably dates to 1857. However, Guelzo is correct that, by reading Chamber’s Vestiges, Lincoln would have been exposed to a distillation of Lyell’s most important ideas. But Lincoln’s earlier interest in geology could have been nourished just as easily by the American edition of Robert Bakewell’s Introduction to Geology (1813), or William Maclure’s Observations on the Geology of the United States of America (1817), or even the 1804 translation of A View of the Soil and Climate of the United States, by Constantin-François Volney, the French deist whose skeptical Ruins of Empires supposedly influenced Lincoln’s religious thinking.[56]

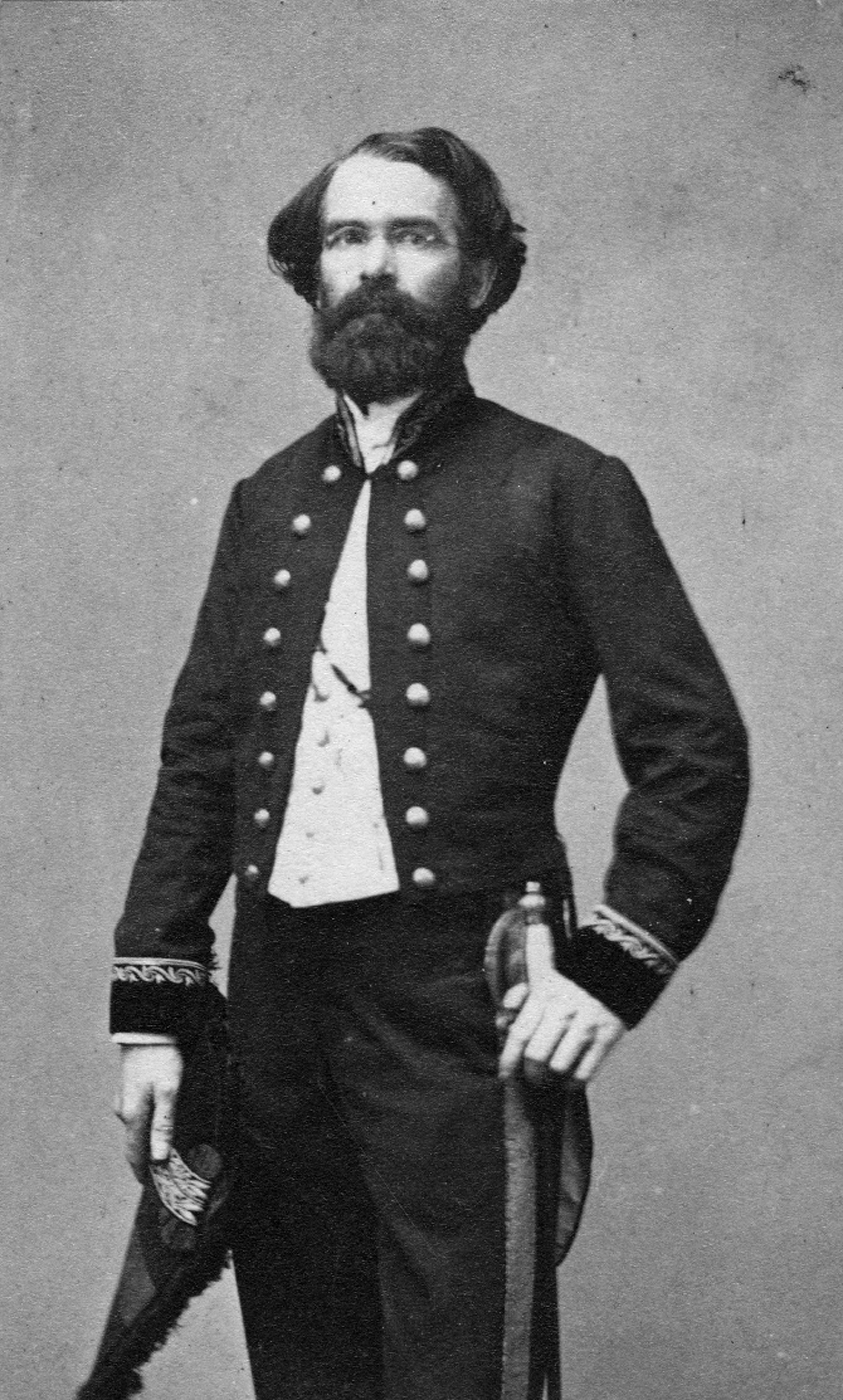

Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society, Image ID 45226. A carte de visite photographed in Paris c. 1864, showing Joseph H. McChesney in court dress, during his service as Lincoln’s consul in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society, Image ID 45226. A carte de visite photographed in Paris c. 1864, showing Joseph H. McChesney in court dress, during his service as Lincoln’s consul in Newcastle upon Tyne.It is notable that the earliest evidence for Lincoln’s interest in geology connected that subject with his religious skepticism. In 1837 one of the court clerks who worked in an office next to Lincoln’s law office was James H. Matheny—nine years Lincoln’s junior but later a groomsman at his wedding. Matheny later recounted to Herndon that: “Lincoln used to talk Infidelity in the Clerks office. . . . Lincoln attacked the Bible & New Testament on two grounds—1st From the inherent or apparent contradiction under its lids & 2ndly from the grounds of Reason—sometimes he ridiculed the Bible & New Testament—sometimes seemed to scoff it. . . . Sometimes Lincoln bordered on absolute Atheism: he went far that way & often shocked me. I was then a young man & believed what my good mother told me. . . . Lincoln would come into the clerk’s office where I and . . . others were writing or staying; & would bring the Bible with him—read a chapter—argue against it.”[57] Significantly, Matheny’s very next sentence is: “Lincoln then had a smattering of Geology if I recollect it.” Apparently, Lincoln was now using “expert testimony,” employing not just reason but also science against revelation.

Lincoln’s interest in geology was nourished by Herndon’s library, by reading Chambers’s Vestiges and Wells’s Annual, and perhaps by Lincoln’s service in the early 1850s on the Board of Canal Commissioners of Illinois.[58] Lincoln also demonstrated his interest in geology in an undated fragment stimulated by a visit to Niagara Falls in 1857.[59] The meditative piece, though ending mid-sentence, demonstrates Lincoln’s scientific cast of mind. “Niagara-Falls! By what mysterious power is it that millions and millions, are drawn from all parts of the world, to gaze upon Niagara Falls? There is no mystery about the thing itself. Every effect is just such as any intelligent man knowing the causes, would anticipate, without [seeing] it. . . . The geologist will demonstrate that the plunge, or fall, was once at Lake Ontario, and has worn it’s way back to it’s present position; he will ascertain how fast it is wearing now, and so get a basis for determining how long it has been wearing back from Lake Ontario, and finally demonstrate by it that this world is at least fourteen thousand years old.”

After discussing the sun’s power to evaporate the vast amounts of water that later rain down and flow across the falls, Lincoln returns to the geological time-scale: “When Columbus first sought this continent—when Christ suffered on the cross—when Moses led Israel through the Red-Sea—nay, even, when Adam first came from the hand of his Maker—then as now, Niagara was roaring here. The eyes of that species of extinct giants, whose bones fill the mounds of America, have gazed on Niagara, as ours do now. Contemporary with the whole race of men, and older than the first man, Niagara is strong, and fresh to-day as ten thousand years ago. The Mammoth and Mastadon—now so long dead, that fragments of their monstrous bones, alone testify, that they ever lived, have gazed on Niagara. In that long—long time, never still for a single moment.”

By saying that “the world is at least fourteen thousand years old” and Niagara “older than the first man,” Lincoln showed an awareness of geologists’ speculations—especially those of Lyell and Hall, who examined the falls together in 1841 and published their results in 1843 and 1845.[60] Lyell and Hall always cautioned against assuming the rate of erosion was constant enough to provide a very clear measure of how long the Niagara River had been spilling over the falls, and their estimates and those of others were extremely varied.[61] But most of the estimates, including Lincoln’s “fourteen thousand years” (for which no exact source has been found), broke with the traditional dating of creation to about 4000 B.C., which in those days was accepted by most people with non-scientific backgrounds. Geologists have in more recent times worked out from other evidence that the Niagara River could not have begun flowing until the recession of the last Ice Age, about 12,000 years ago. So, whatever source Lincoln found for his dating, it was a surprisingly good one.

Lincoln’s interest in geology—or at least in the related subject of metallurgy—is shown in the lyceum-style lecture on “Discoveries and Inventions” that he prepared sometime in the 1850s and delivered several times between April 1858 and April 1860.[62] One account of how Lincoln came to produce such a lecture was given by the wife of Lincoln’s fellow lawyer and political ally, Norman Judd. Mrs. Judd said Lincoln and a friend once discussed “the relative age of the discovery and use of the precious metals [after which] he went to the Bible to satisfy himself and became so interested in his researches that he made memoranda of the different discoveries and inventions.” Lincoln became “convinced . . . that the subject would interest others, and he therefore prepared and delivered his lecture on The Age of Different Inventions.”[63] Mrs. Judd’s reference to “precious metals” rings true as one of Lincoln’s interests, and the lecture actually began with the line, “All creation is a mine, and every man, a miner.”[64] However, the lecture actually reflected a broader interest than either geology or metallurgy, and Lincoln’s few direct references to metal were deployed partly to allow him to crack a somewhat irreverent joke. In the midst of listing the earliest references to iron and brass that he could find in the Old Testament, Lincoln said, “We can scarcely conceive the possibility of making much of anything else, without the use of iron tools. Indeed, an iron hammer must have been very much needed to make the first iron hammer with.”[65]

Lincoln’s genuine interest in scientific discoveries and inventions would serve him—and the nation—well in subsequent years. His ability to understand the mechanics behind the new reaping machines aided Lincoln when researching a legal case about patent-infringement.[66] In 1859 Lincoln addressed the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society, stressing the need for exploiting “recent discovery, or invention,” citing Patent Office reports on crop yields per acre, advocating “deeper plowing, analysis of soils, experiments with manures, and varieties of seeds, observance of seasons, and the like,” arguing for “the successful application of steam power,” and mentioning the assistance to be gained from botany, chemistry, and “the mechanical branches of Natural Philosophy . . . especially in reference to implements and machinery.”[67] As president, Lincoln must deserve at least some of the credit for the Department of Agriculture and the visionary Morrill Land Grant College Act, both created in 1862.[68]

When Lincoln was negotiating in 1862 for a piece of land in Central America that might have been used for the colonization of freed slaves—the Chiriqui scheme, promoted by the dishonest landowner, Ambrose W. Thompson, and his political supporters, the Blair family—Lincoln was not fooled by the false claims about the potential value of the coal deposits in the region. By turning to the director of the Smithsonian Institution, Joseph Henry, with whom Lincoln had developed a fine rapport, he was able to obtain indirectly the technical advice of one of the nation’s leading authorities on coal, J. Peter Lesley, of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. That information helped Lincoln to avoid being misled by earlier geological reports, which had been suspiciously positive.[69]

Throughout the Civil War Lincoln’s interest in new technology played a significant role in bringing a Union victory. It is well known that Lincoln worked closely with the innovative Captain John A. Dahlgren, chief of ordnance at the Washington Navy Yard, and also overcame the objections of the less enterprising army chief of ordnance, General James Ripley. Lincoln examined, and in many cases personally tested, new weapons brought to him by inventors. As Robert V. Bruce, the best authority on Lincoln’s interest in weapons, said: “During the Civil War, the nearest thing to a research and development agency was the President himself.”[70] And there is certainly evidence to suggest that without Lincoln’s personal intervention, the use of ironclad gunboats in the river campaigns in the West and the development of John Ericsson’s revolutionary Monitor design might not have occurred, or at least not early enough to be as beneficial as they were.[71] Less well known is that during the crisis known as “The Trent Affair,” late in 1861, the most important factor influencing Lincoln’s decision about the release of the two Confederate emissaries seized from a British vessel was not the illegality of the act or even the considerable risk of open warfare with Britain, but rather Lincoln’s clear understanding of a technological issue: that an angry British cabinet had cut off the flow of niter—the “saltpeter” used in gunpowder—and that Lincoln could not continue the war without it. As soon as the immediate crisis was resolved, Lincoln pushed for the development of a substitute for the British-controlled niter, even personally arranging for the only chemist employed by the federal government to spend months and thousands of dollars trying to develop a new gunpowder formula.[72]

Lincoln’s interest in science may well have been nourished by Herndon’s library, but of course the law partners also shared a deep interest in slavery and the related issue of racial theories. In his biography of Lincoln, Herndon wrote: “I was in correspondence with Sumner, Greeley, Phillips, and Garrison, and was thus thoroughly imbued with all the rancor drawn from such strong anti-slavery sources. . . . Every time a good speech on the great issue was made I sent for it. . . . Lincoln and I took such papers as the Chicago Tribune, New York Tribune, Anti-Slavery Standard, Emancipator and National Era. On the other side of the question we took the Charleston Mercury and the Richmond Enquirer. . . . I purchased all the leading histories of the slavery movement, and other works which treated on that subject.”[73]

Numerous books on slavery—and journals and newspapers that contained reviews of such works—are mentioned in Herndon’s auction list, including George Fitzhugh’s Sociology for the South, which, according to Herndon, “defended and justified slavery in every conceivable way” and also “aroused the ire of Lincoln more than most pro-slavery books.”[74] When Fitzhugh published that work in 1854 he had not yet converted (but did seven years later) to the view then developing and known today as “scientific racism,” a pseudo-scientific argument for the view that blacks were inferior because their race was a “separate creation,” which meant they were practically a different species from “white men.” A number of scientists, including Dr. Samuel Morton, Dr. Josiah Nott, and Ephraim Squier, promoted that view in the 1840s and 1850s, but it gained added currency through the support given by the Harvard professor who was at the time the best-known naturalist in America, Louis Agassiz. “Scientific racism” became part of the political discourse of the time and can be seen—without resort to much of the technical terminology—in the speeches of Alexander H. Stephens and, more notably, of Stephen A. Douglas. In his debates with Douglas, Lincoln parried these arguments while clinging to the concept that all men are created equal.

Although Agassiz made many important contributions to natural history, he is best known today for his stubborn rear-guard action against Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Although Herndon’s auction list included Darwin’s Origin of Species, the evidence suggests that Lincoln never read that work, which appeared in late 1859, when Lincoln was pre-occupied with the task of getting nominated and elected president. However, it is inconceivable that he was not aware of the scientific debate about species development, although it is impossible to say whether he grasped the degree to which Darwin’s research was fueled by Darwin’s own hatred of slavery and desire to demonstrate that all races of men have a common origin—a point highlighted by Darwin scholars Adrian Desmond and James Moore in their recent book, Darwin’s Sacred Cause.[75] And it is an interesting fact that in January 1865 Lincoln had a conversation with Agassiz in the White House that was reported in three different accounts by an eye-witness, Lincoln’s journalist friend, Noah Brooks.[76]

The exchange of views must have been somewhat bizarre, and seems to have puzzled Brooks. “The conversation, however, was not very learned. The President and the savant seemed like two boys who wanted to ask questions which appeared commonplace, but were not quite sure of each other. Each man was simplicity itself.” While Brooks recognized that Lincoln was somehow engaged in a “gentle cross-examination of Agassiz, . . . how the Professor studied, how he composed, and how he delivered his lectures; how he found different tastes in his audiences in different portions of the country,” Brooks was left wondering why “no questions were asked about the Old Silurian, the Glacial Theory, or the Great Snow-storm.”[77]

Brooks gave two different versions of the interview’s end. The first was written only weeks after Lincoln’s death: “When afterward asked why he put such questions to his learned visitor [Lincoln] said, ‘Why, what we got from him isn’t printed in the books; the other things are.’”[78] This alone indicates that Lincoln was well-aware of Agassiz’s views on different matters, and certainly his well-known opinions about the black race were bound to be abhorrent to Lincoln.

It is probably a testament to Lincoln’s grasp of that scientific debate—and to his confidence in his own understanding of science—that (according to Brooks’s later version of the story, written in 1878) after Agassiz and Lincoln finished by “shaking hands with great warmth” and the professor had departed, the president “turned to me with a quizzical smile and said, ‘Well, I wasn’t so badly scared, after all! were you?’”[79]

[Transcription, without annotation, of Herndon’s Auction List, Printed Ephemera Collection, Library of Congress, control number 98149366]

By W.O. Davie & Co.

At Book Sale Rooms, 16 East Fourth Street, Cincinnati

The private library! of W.H. Herndon, Esq. (former law partner of Hon. Abraham Lincoln), at auction on Friday and Saturday evenings, Jan. 10 and 11, 1873, at 7 o’clock each evening / by W.O. Davie & Co., at book sale rooms, 16 East Fourth Street, Cincinnati.

The Library consists of about 1,000 volumes, containing many desirable works in BIOGRAPHY, HISTORY, SCIENCE, NATURAL HISTORY, SOCIAL SCIENCE, PHYSIOLOGY, PSYCHOLOGY, POLITICAL ECONOMY, INDUCTIVE and SPECULATIVE PHILOSOPHY, LIBERAL THEOLOGY, LITERATURE and ARTS, ETC. Also, writings on Slavery, pro and con, and a few Law Books. To be sold in the following order:

- Allen, Wm. The American Biographical Dictionary. The last edition. Royal 8vo Sheep. Boston, 1857

- Allen, D.O. India, Ancient and Modern. 8vo. maps

- Allen, Z. Philosophy of the Mechanics of Nature, and the Source and Modes of Action of Natural Motive Power. Numerous wood cut illustrations. Thick 8vo N.Y., 1852.

- Abbott, J.S.C. Empire of Russia

- Ansted, D.T., M.A. The Great Stone Book of Nature. Illustrated.

- Anthon’s Smith’s Classical Dictionary. 8vo, sheep

- Alison, A. Principles of Taste.

- Agassiz, Louis. Structure of Animal Life Illustrated 8vo

- ———. Methods of study in Natural History. Illustrated

- Adams, J.Q. Memoir of the Life of. By Josiah Quincy. 8vo, Portrait

- ———. Life and Public Services of . By W. H. Seward

- Art and Industry at the N.Y. Crystal Palace in 1853-‘54. From the Tribune

- Abelard and Heloise. By O.W. Wight

- Annual of Scientific Discovery, 1854

- American Almanac, 1856. Half calf.

- Autographs for Freedom. Boston, 1853.

- American Archives. Vols 2 and 3 (1776), folio, half Russia

- Annals of Congress and Congressional Debates: From the First to the Twenty-fifth Congress inclusive excepting the Seventeenth and the First Session of the Eighteenth Congress. 65 volumes, sheep, in fine conditions

- Beecher, Catherine K. Common Sense Applied to the Religion

- Beecher, H. W. Life thoughts

- Beecher, R. Conflict of Ages

- Bartlett, D.W. Modern Agitators; or Pen Portraits of American Reformers, N.Y. 1855.

- Breughel Brothers. From the German, Illust.

- Bryant, Wm. Cullen. Poems of

- Blair, Hugh. Sermons. 8vo, sheep, worn

- Blood, B. Optimism the Lesson of Ages

- Bascom, H.B., D.D. Sermons

- Boyd, Rev. J.R. Moral Philosophy

- Bayne, P. The Christian Life, Social and Individual

- ———. Essays in Biography, etc.

- Baker, G. E. Life of Wm. H. Seward

- Bacon’s Essays, with Annotations by Richard Whateley, 8vo

- Brownson, O.A. Essays and Reviews

- Bliss, S. On the Apocalypse

- Blakely, Rev. J. Theology of Inventions

- Bowen, F. Principles of Political Economy. 8vo

- British Eloquence. 4 vols. 16mo

- Bastiat, F. Harmonies of Political Economy. 8vo.

- Bailey, P.J. The Mystic and Other Poems

- Blanc, Louis. History of Ten Years, 1830–1840. 2 vols., with map of Paris

- Buist’s Am. Flower Garden Dictionary

- Buchanan’s Anthropology. 8vo, half Turkey morocco

- Buchanan, James. Modern Atheism: Pantheism, Materialism, Secularism, etc.

- Biography of Oliver Cromwell

- Bookman, J. History of Inventions, Discoveries, and Origins. 2 vols. (Bohn).

- Bancroft, Geo. Literary and Historical Miscellanies. 8vo

- ———. History of the United States. Vols 1 to 8 inclusive. 8vo

- Baird, Wm. Cyclopedia of the Natural Sciences. With maps and illustrations. 8vo.

- Brace, Chas L. The Races of the Old World: A Manual of Ethnology. 8vo. N.Y. 1863

- Buck’s Theological Dictionary. 8vo sheep

- Birch, W.J. An Inquiry into the Philosophy and Religion of the Bible

- Bulwer’s What Will He Do With It. 8vo paper

- ———. Caxtoniana

- Buckle, H.T. History of Civilization in England. 2 vols., royal 8vo

- Burke, Edmund. Life and Character of. By James Prior. 2 vols

- Congressional Globe. 44 vols. 4to

- Calhoun, J.C. Life of

- Child, L. Maria. Progress of Religious Ideas through Successive Ages. 3 vols. 8vo

- Calderwood, H. Philosophy of the Infinite. 8vo

- Curtis, Geo. W. Prue and I

- Cabinet Gazetteer. Thick 16mo, map

- Carpenter, W.B. Use and Abuse of Alcoholic Liquor. Stained

- Calvert, G.H. Social Science

- Cyclopedia of Biography. Numerous illustrations, Thick 8vo. London, 1854

- Constitution of the U.S., etc. By W Hickey

- Cruden’s Condensed Concordance 8vo. sheep

- Considerations on Some Recent Social Theories. Boston, 1853

- Conway, M.D. Tracts for To-day

- Camp, G. S. Democracy. 16mo

- Carlyle, Thomas. Past and Present, Chartism, and Sartor Resartus, in 1 vol

- Carlyle, Thomas. Heroes and Hero Worship

- ———. Latter day pamphlets

- ———. French Revolution. 2 vols

- ———. Critical and Miscellaneous Essays. 4 vols

- ———. Sartor Resartus, and Lectures on Heroes, in 1 vol

- ———. Sartor Resartus.

- Canning’s Speeches 8vo. sheep.

- Creasy, E.S. Rise and Progress of the English Constitution

- Comte, Auguste. Positive philosophy. 2 vols., 8vo

- ———. Philosophy of the Sciences. (Bohn)

- Clapp, T. Sketches, etc., During a 35 year’s residence in New Orleans. 1857

- Cousin, Victor. Course of the History of Modern Philosophy. 2 vols., 8vo

- ———. Philosophy of the Beautiful.

- ———. Elements of Psychology

- ———. Lectures on the True, The Beautiful and the Good. 8vo

- Channing, Wm. E. Memoir of. 3 vols.

- ———. Works of. 6 vols.

- Carey, H.C. Principles of Social Science. 3 vols., 8vo. Phila. 1855.

- Case of Passmore Williamson. 8vo. Phila. 1856.

- Chalybaus, Dr. H.M. Historical Development of Speculative Philosophy, from Kant to Hegel. 8vo

- Correlation and Conservation of Forces. By Grove Helmholz, Faraday, Liebig, etc.

- Coues, S.K. Mechanical Philosophy

- Chase and Sanborn. Statistical View of the Free and Slave States. Boston, 1856.

- Chapin, E. H. Moral Aspects of City Life

- Chambers’s Repository. 6 vols. Illustrated

- Cayley, E.S. European Revolutions of 1848. 2 vols

- Carpenter, W.B., M.D. Principles of Human Physiology. 261 Illustrations. 8vo ‑sheep. Phila. 1855.

- ———. Mechanical Philosophy, Horology, and Anatomy

- Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches. With elucidation by Thomas Carlyle. 2 vols

- Combe, Geo. The Constitution of Man in Relation to External Objects

- ———. Lectures on Phrenology

- Coultas, H. Organic Life the Same in Animals as in Plants

- Carey, H.C. The Past, the Present, and the Future. 8vo

- Chapin, E.H. Characters in the Gospels

- ———. Select Sermons

- ———. Discourses on the Beatitudes

- Diplomatic Correspondence. Foreign Affairs(1862) and Mexican Affairs. 3 vols. Half morocco.

- Dunckley, H. Charter of the Nations; or, Free trade and its Results. 8vo. London 1854

- De Tocqueville, A. Democracy in America. Notes, etc. by Francis Bowen. 2 vols. 8vo. Cambridge, 1863.

- De Coureillon, E. Social and Religious Customs in France

- Davis, A.J. An Autobiography of

- Davis, A.J. Penetralia: Harmonial Answers to Important Questions. 8vo

- Draper, J.W. Thoughts on the Future Civil Policy of America. 8vo. N.Y., 1865

- D’Aubigne, J.H.M. The Protector

- Dods, J.B. Spirit Manifestations Examined and Explained

- ———. Electrical Psychology

- Draper, J.W. Human Physiology, Statistical and Dynamical. Nearly 300 Illustrations. 8vo

- Dove, P.E. Elements of Political Science. 8vo Edinburgh, 1854.

- Davey, Joseph Logic. (Bohn’s edition)

- De Quincey, Thos. Opium Eater

- ———. Biographical Essays

- ———. Closterheim or the Masque

- Darwin, Chas. Origin of Species

- Dietetics of the Soul. 16mo

- Dall, Caroline H. Womans Rights Under The Law. 16mo

- ———. Women’s Right to Labour, 16mo

- Debates Between Lincoln and Douglas. 8vo

- Don Quixote. 4 vols. 32mo. sheep

- Eminent Men and Popular Books. 16mo

- Essays from the London Times. Personal and Historic Sketches. 16mo

- Essays from the London Times, 2nd Series

- Essays and Reviews; Miscellaneous. 8vo London 1860

- Essays on Intuitive Morals. Boston, 1859

- Essays. Oxford Essays for 1856, ’58. 2 vols. 8vo. boards

- ———. Edinburgh Essays, 1856. 8vo, boards

- ———. Cambridge Essays, 1857, 8vo. boards

- English Pulpit. A Contribution of Sermons by the Most Eminent Divines. 8vo

- Emerson, R. W. Works of, viz: Representative Men; Essays, 1st and 2d Series; Nature. Addresses and Lectures; Poems; Conduct of Life; English Traits. 7 vols

- Eliot, Samuel. Manual of United States History from 1492 to 1850

- ———. History of Liberty. 2 vols. 8vo

- Eliot W. G. Lectures to Young Men

- Eliot, Jonathan. Debates on the Federal Constitution. Vols. 1 and 2. 8vo. Sheep. Washington, 1836

- Everett, Edward. Orations and Speeches on Various Occasions. 3 vols. 8vo

- Foster, John. Essays of

- Farrar, Adam S. A Critical History of Free Thought in Reference to Christian Religion.

- Fichte, Johann G. Popular works of. 2 vols., portrait

- Fichte, I.H. Mental Philosophy. 16mo

- Francis, New York Guide. 18mo, illust

- Ferguson, A. History of the Roman Republic. With map. 8vo. sheep.

- Feuerbach, L. Essence of Christianity. 8vo

- Flagg, W. Studies in the Field and Forest

- Farness, W.H. Discourses by

- Farnham, E.W. Woman and Her Era. 2 vols

- Forster, John. Historical and Biographical Essays. 2 vols. 8vo

- Fleming, W. Vocabulary of Philosophy

- Froude, J. A. Short Studies on Great Subjects

- Franklin, Benjamin. Life of. By Jared Sparks. 8vo

- Faraday, M. On the Various Forces Of Matter. Numerous illustrations. 16mo

- Gilfillan, Geo. Modern Literature and Literary Men

- ———. Bards of the Bible

- Goethe’s Faust. Hayward’s Translation

- Guizot, F. History of Civilization. 4 vols

- Guizot on Civilization. Sheep. Worn

- Gregory’s Organic Chemistry. 8vo, half roan

- Gibbon, Edward. History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. 4 vols. 8vo. sheep

- Greeley, Horace. Political economy

- ———. Hints Toward Reform

- ———. History of the Struggle for Slavery Extension or Restriction. Thin 8vo. N.Y. 1856

- ———. Glances at Europe

- Grattan’s History of the Netherlands. 16mo.

- Greene, G.W. Historical View of the American Revolution. Boston, 1865

- Gurowski, Count. Russia As It Is. N.Y. 1854

- Gurowski, A. Slavery in History

- Gurowski, A.J. America and Europe.

- Greg, W.R. The Creed of Christendom

- Godwin, Parke. Political Essays

- Gouge’s Journal of Manking, 1841–2. 8vo

- Goodell, Wm. Slavery and Anti Slavery; The Great Struggle in Both Hemispheres. 8vo

- Giddings J. R. Speeches in Congress

- Geary and Kansas. Phila., 1857

- Goadby, H. Textbook of Vegetable and Animal Physiology. 450 illust. 8vo.

- Hamilton, Dr. G. Animal Physiology. Thin 16mo

- Haven, Jos. D.D. Mental Philosophy. 8vo.

- Hazard, R.G. On the Will

- Hamilton, Sir Wm. Discussions on Philosophy and Literature, Education and Reform. 8vo

- Hall, B.F. The Republican Party and Its Candidates. New York, 1856

- Hallam, Henry. Constitutional History of England. 3 vols.

- ———. View of the State of Europe During the Middle Ages. 3 vols.

- ———. Middle Ages. 8vo. Sheep

- Hale, David. Memoir of. With Selections from his Writings. 8vo

- Hardy, R.S. Manual of Budhism in Its Modern Development. 8vo

- Hennell, S.S. Christianity and Infidelity: Exposition of the Arguments on Both Sides. 8vo

- Hildreth, Richard. History of the United States from the Discovery of the Continent to 1820. 6 vols, 8vo, gilt tops

- ———. Theory of Politics

- History of Wonderful Inventions. Numerous illustrations

- History of Queen Elizabeth. Worn

- Hickok, L. Rational Cosmology; Eternal Principles and Necessary Laws of the Universe. 8vo

- Hickok, L.P. Science of the Mind.

- Hitchcock, E. Religious Truth Illustrated from Science.

- Howitt, W. History of Priestcraft

- Heine, Henry. Pictures of Travel. Half morocco

- Hitchcock, E. Religion of Geology and Its Connected Sciences

- Huc, M. A Journey Through the Chinese Empire. 2 vols., map

- Huc, Abbe. Christianity in China, Tartary and Thibet. 2 vols

- Hunt, R. Elementary Physics: Introduction to Natural Philosophy. Numerous Illustrations. (Bohn’s Edition)

- ———. Poetry of Science. (Bohn)

- Hunt, Leigh. Stories from Italian Poets

- Hume’s History of England. 6 vols

- Humboldt, Alexander. Cosmos. 5 vols (Bohn)

- ———. Sphere and Duties of Government

- Humphreys, E. R. Political Science. Flex.

- Huxley, T.H. Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature. Illustrated.

- ———. On the Origin of Species

- Illinois Real Estate Laws. 8vo, sheep. Quincy, 1849

- ———. Laws. Vandalia, 1833

- ———. Agricultural Society Translations. Vols 4, 5, 6. 1859-’66

- Illinois in 1837-’56. 8vo, boards

- In Memoriam, J.W.B. Boston, 1860

- James, H. Lectures and Miscellanies

- Jarves, J.J. Art Hints: Architecture, Sculpture and Painting

- ———. The Art Idea. 16mo.

- Johnson, W.R. On the Use of Anthracite in the Manufacture of Iron.

- James, H. Moralism and Christianity

- Josephus’ works. Whiston. 8vo, sheep

- Jameson, Mrs. Commonplace Book of Thoughts, Memoirs and Fancies

- Jefferson, Thos. Notes on the State of Virginia. 18mo, sheep. Boston, 1829

- Jewett, C. Lectures, etc. On Temperance

- Jennings, R. Political Economy

- James, Henry. Nature of Evil

- Journal of the Convention Which formed the Constitution in 1787. 8vo, sheep.

- Kossuth’s Select Speeches. Portrait

- Knight, Chas. Knowledge is Power, Results of Labor, Capital and Skill, etc. Numerous illustrations.

- Kellogg, E. New Monetary System, N.Y. 1861

- Kennedy’s Demosthenes. 2 vols. (Harper)

- Lazarus, M.E. Passional Hygiene.

- Lectures on Education Delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain.

- Lewes, G.H. Life and Works of Goethe. 2 vols

- ———. Biographical History of Philosophy, from Its Origin in Greece. 8vo

- ———. Physiology of Common Life. 2 vols

- Lytton, Sir E.B. Harold

- Lyell, Sir Chas. Manual of Elementary Geology. With 750 woodcuts. 8vo, revised edition.

- Livermore, A.A. War with Mexico. Reviewed. Boston, 1850

- Laws of Illinois. Boards. 1839

- Laws of Kansas. 8vo, half Russia

- Leckey. W.R.H. History of Rationalism in Europe. 2 vols., 8vo

- Lewis, Prof. T. Six Days of Creation.

- Lynch, T.T On Self Improvement.

- Laing, S. Social and Political State of European People in 1848-‘9. 8vo

- Langel, Auguste. The United States During the War. 8vo

- Lamartine’s History of the Girondists. 3 vols.

- ———. Memoirs of Celebrated Characters. 3 vols.

- Lieber, F. On Civil Liberty and Self-Government. 2 vols. Phila. 1853.

- Lieber, Francis. On Civil Liberty and Self-Government. 8vo, enlarged edition

- Lossing, B.J. Outline of the History of the Fine Arts. 18mo

- Loomis, E. Recent Progress of Astronomy.

- Mann, Horace. Duties, etc., of Woman. 16mo flex

- ———. Dedication of Antioch College

- ———. Letters and Speeches on Slavery

- ———. Lectures on Education

- Madison and Monroe. Lives of. By John Quincy Adams

- Martineau, Rev. J. Miscellanies by

- Martineau, Jas. Studies of Christianity

- Markham’s History of France. School edition

- Maine, H.S. Ancient Law: Its Connection with the Early History of Society, etc 8vo. N.Y. 1864.

- Maurice, F.D. Learning and Working, and Religion of Rome, in 1 vol.

- ———. Religions of the World and their Relations to Christianity

- ———. Theological Essays

- Macon, Hon. Nath. Life of. Baltimore, 1840

- Mahan, Rev. A. Intellectual Philosophy

- Manchester Papers. 1856

- Macvicar, J.G. Philosophy of the Beautiful. With illustrations.

- Mariotti, L. Italy in 1848

- Marsh, G.P. Man and Nature: or Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. 8vo. NY 1864

- Macnaught, Rev. J. Doctrine of Inspiration

- Mackay, R. W. Rise and Progress of Christianity

- Maccall, W. Agents of Civilization. 16mo

- Maps to Andrew’s Report

- Massachusetts Agricultural Society Transactions., 1865–9 4 vols.

- Memorial Addressses on the Life and Character of A. Lincoln. Thin 8vo. Portrait

- Macaulay’s Speeches. 2 vols.

- Maccall Wm. Elements of Individualism.

- McPherson’s Political Manual for 1866.

- McCulloch, J.R. Principles of Political Economy. 8vo.

- Meagher, T.F. Speeches on the Legislative Independence of Ireland

- Memphis Riots Report. 1866.

- Mill, John Stuart. System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive. 8vo

- ———. Principles of Political Economy. 2 vols. 8vo

- ———. Dissertations and Discussions. 2 vols. 8vo

- ———. Auguste Comte and Positivism. 8vo

- ———. On Liberty.

- Mignet, F.A. History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814. (Bohn)

- Miller, Hugh. Footprints of the Creator. Illustrated.

- ———. Popular Geology.

- Moffatt, J.C. An Introduction to the Study of Aesthetics

- Moore, Thomas. Lalla Rookh

- Modern British Essayist, viz: Macaulay, Jeffrey, Macintosh, Talfourd, and Stephens. 4 vols. 8vo. Sold separately

- Morell, J.D. Introduction to mental Philosophy on the Inductive Method. 8vo

- Morell, J.D. Philosophy of Religion. 8vo

- ———. Philosophical Tendencies of the Age. Thin 8vo

- ———. Elements of Psychology. Part 1

- Motley, J.L. History of the Rise of the Dutch Republic. 3 vols. 8vo

- Muller, Max. Lectures on the Science of Language. First series.

- New American Cyclopaedia. Edited by George Ripley and Charles A. Dana. 16 vols., Royal 8vo, sheep

- Nichol, J.P. Cyclopaedia of Physical Sciences, with maps, engravings, and numerous wood-cuts. 8vo

- New Biographies of Illustrious Men. By Macaulay, Rogers, and others.

- Newman, F.W. Political Economy.

- Obituary Addresses on the Death of Henry Clay.

- ———. Addresses on the Death of Webster.

- Occult Sciences: Traditions, Superstitions, and Marvels. By Smedley, Taylor, etc.

- Oersted, Hans C. The Soul in Nature. ––(Bohn)

- Osgood, S. God with Men

- Owen, Robert Dale. Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World.

- Owen, R. Key to the Geology of the Globe. Illustrated by Maps and diagrams. 8vo.

Odd Volumes

- Chambers’s Journal Of Popular Literature, Arts and Sciences. Vols 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12. Royal 8vo

- Greeley’s American conflict. Vol 1. Royal 8vo, sheep. Illustrated.

- Michelet’s History of France. Vols. 1 and 2. 8vo

- Macaulay’s England. Vols. 1 and 2. 8vo.

- Thiers’ History of the Consulate and Empire. Vols. and 2. 8vo. half bound.

- Works of Daniel Webster. Vols. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6. 8vo

- Irving’s Life of Washington. Vol 1, 8vo

- Vaughan’s Revolution in English History. Vol. 1. Revolutions of Race. 8vo

- Webster’s Speeches. Vol. 2. 8vo, sheep

- Buckle’s History of Civilization. Vol. 1. 8vo

- Life, etc., of Clay. Vol. 1. 8vo. bds

- Brown’s Philosophy. Vol. 2 8vo, sheep.

- Curtis’ History of the Constitution of the United States. Vol. 1, 8vo

- Works of Calhoun. Vol. 1, 8vo

- Chambers Papers for the People. Vols 1, 2, 3, 5, 6

- Carlyle’s Fredrick the Great. Volumes 1 and 4

- Irving’s Mahomet. Vol. 1

- Silliman’s Visit to Europe. Vol. 1

- Headley’s Washington and Generals. Vol 1

- Mill on Hamilton’s Philosophy. Vol. 2

- De Lamartine’s Restoration of Monarchy. Vol. 1

- Spencer’s principles of Biology. Vol 1

- Bigelow’s Useful Arts. Vol. 2

- Lot (22) Odd Volumes

- Parker, Theodore. Speeches, Addresses and Occasional Sermons. 2 vols

- ———. Additional speeches, etc. 2 vols

- ———. Miscellaneous Writings. Boston, 1856.

- ———. Life and Correspondence of. By John Weiss. 2 vols., 8vo

- Parker, E.G. The Golden Age of American Oratory.

- Patterson, J. Charles Hopewell

- Paley’s Philosophy. 2 vols. in 1, sheep

- Palgrave, F.T. Essays on Art. N.Y. 1867

- Page, D. introductory Text-Book of Geology. Illustrated, 16mo. flexible.

- Parisian Lights seen through American Spectacles

- Patent Office Reports 1847, ’48, ’51 (Mech.); ’54, ’56 to ’61 (Agricultural). 10 vols.

- Public Documents: Messages and Documents, Patent Office Reports, etc. 62 vols.

- Peabody, A. P. Christianity the Religion of Nature.

- Perry, A.L. Political Economy

- Popular Biography. By Peter Parley. Illustrated

- Pope’s Homer’s Iliad. Worn

- Pierson, J. The Judiad. St. Louis, 1844

- Putnam, G.P. The World’s Progress: a Cyclopaedia of Chronology. 8vo. N.Y., 1855

- Philosophy of Sir Wm Hamilton. 8vo

- Philosophy of Kant: Lectures by Victor Cousin

- Philippsohn, Dr. L. Development of the Religious Idea in Judaism, Christianity and Mohamedanism. 8vo

- Plurality of Worlds

- Press (The) and the Public Service

- Priesthood and Clergy Unknown to Christianity. Phila. 1857

- Prentice’s Biography of Henry Clay

- Psychological Inquiries. London 1854

- Parker, Theodore. His Experience as a Minister, with some account of his early life. 12mo. paper

- ———. 13 Sermons and Addresses on various subjects

- Pamphlets. Legal Arguments and Decisions

- ———. Political

- ———. Miscellaneous

- ———. Historical and Miscellaneous

- ———. New England and the Pilgrim Fathers

- ———. New York Historical Society

- ———. Science and Natural History

- ———. Social Science

- ———. Anti-Slavery

- ———. Sermons and Addresses on Slavery, pro and con

- ———. Reports of the American and the Am. and For. Anti-Slavery Societies

- ———. Speeches of Daniel Webster and Addresses on his Death.

- ———. Life and Speeches of, and Eulogies on President Lincoln

- ———. Pulpit politics

- ———. 17 Unitarian Sermons by various Authors

- ———. 7 Tribune Almanacs, 1854, ’56, ’58, ’59, ’61 and ’65

- ———. 2 Merchant and Banker’s Almanacs, 1856 and 1857

- ———. Catalogues of Fruit and Ornamental Trees, Seeds, etc.

- Periodicals. 3 North American Review. Nos. 176, 180, 181

- ———. 4 National Review. Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4. London

- ———. 14 North British Review. Not consecutive

- ———. 49 Westminster Review. 1851–1868. Not consecutive.

- ———. 5 do. do. Duplicate. Nos. 112, 114, 115, 116 and 119.

- ———. 15 London Quarterly, Edinburgh, Blackwood and Chambers

- ———. 9 Putnam, Atlantic, etc.

- ———. 5 Biblical Repository, Christian Review, and Methodist Quarterly

- ———. 6 Littell’s Living Age and Eclectic

- ———. 28 Tilton’s Journal of Horticulture, not consecutive

- ———. 9 do do do Duplicates.

- Paper bound books. Cambridge Essays, Contributed by members of the University. 2 vols. 8vo. 1856, 1858.

- ———. Hay, D.R., F.R.S. Natural Principles of Beauty

- ———. Englishman in Kansas, and Crystal Palace. 2 vols.

- ———. Sociology for the South. by G. Fitzhugh and the Crisis of 1861, by A.D. Streight. 12mo. 2 vols.

- ———. Newman’s Letters from Turkey, Gervinus’ History of the 19th Century, &c. 3 vols. 18mo

- ———. Cabinet of Reason, vols I, III, IV, V 18mo. London. 1854

- ———. 6 Small Works, Literary and Scientific.

- Questions of the Day, by the Creature of an Hour. 1857.

- Ray, I. Treatise on Medical Jurisprudence of Insanity. 8vo.

- Raymond, H.J. Administration of Lincoln

- Randolph, John. Life of. 2 vols.

- Richelieu; or the Broken Heart. Boards

- Rickards, G.K. Population and Capital

- Robertson, , Rev. F.W. Sermons. 1st and 2d series. 2 vols

- Ruskin’s Lectures on Architecture and Painting. With Illustrations by the Author

- Ruskin’s Political Economy of Art

- Russell, R. North America: Its Agriculture and Climate. With map. 8vo

- Ryle, Thos. American Liberty and Government Questioned

- Sargant, W.L. Social Innovators and their Schemes

- Schleiden, M.J. Poetry of the Vegetable World: Botany and Its Relations to Man. Illust.

- Schiller’s Thirty Years’ War. 16mo

- Schiller’s Aesthetic Prose

- Schiller, F. Life of. By Thos. Carlyle

- Schwegler, A. History of Philosophy in Epitome

- Scott, Sir Walter. The Crusades. Sheep

- Scott, G.G. Secular and Domestic Architecture, Present and Future. 8vo, London, 1857

- Senate and Congressional Documents. 48 volumes, odd and assorted, sheep

- Sears, E.H. Foregleams of Immortality

- Sheridan, Richard Brinsley. Memoir of. By Thomas Moore. 2 vols.

- Shakespeare’s Works. 2 vols, 8vo, sheep, Illustrated

- Shehan’s Life of Stephen A. Douglas

- Simon, Jules. Natural Religion

- Sketches on Italy. London, 1856

- Smith, E. F. Political Economy

- Smith, Jas. The Christian’s Defense. 8vo, sheep.

- Smith, G. Lectures on the Study of History, Delivered in Oxford, 1859-‘61

- Smith, Alexander. Poems by

- Space, Time and Eternity. 18mo. flex

- Sparks’ Life of Washington. 2 vols in 1

- Sparks’ Life and Treason of Arnold. 18mo

- Spectator, The. 2 vols in 1, 8vo, sheep.

- Spencer, Herbert. Essays by. Second series, 8vo

- ———. On Education.

- ———. Social Statistics: Conditions Essential to Human Happiness. 8vo

- ———. Essays: Scientific, Political and Speculative. 8vo

- ———. First Principles of a New System of Philosophy. New York, 1864

- Spurgeon’s Sermons. Second Series

- Stanton, H.B. Reforms and Reformers of Great Britain and Ireland

- Sfallo, J.B. Philosophy of Nature

- Sterling, John. Life of. By Thos. Carlyle

- Stockhardt’s Chemistry of Agriculture. Bohn

- Stoddart, Sir J. Introduction to the Study of Universal History

- Story, J. On the Constitution of the U.S.

- St. John, J.A. Nemesis of Power. 18mo

- Studies in Poetry. Sheep, back broken

- Sumner, Chas. Orations and Speeches. 2 vols Boston, 1850

- ———. Speeches and Addresses. Boston, 1850.

- Talbot and Vernon. A Novel

- Taylor. W.C. The Modern British Plutarch.

- Taylor, Rev. R. The Devil’s Pulpit.

- Taine, H. Philosophy of Art. 16mo

- Texas Almanac. 1857- ’8 -’63. Paper

- Togg’s Dictionary of Chronology. From the Birth of Christ. New York, 1854.

- Thackery, W.M. English Humorists of the Eighteenth Century

- Thiers’ History of the French Revolution. 4 vols in 2, 8vo, sheep

- Theory of Progression, and natural Pro[b]ability of a Reign of Justice

- Tocqueville, A. The Old Regime and the Revolution

- Tuckerman, H.T. Essays, Biographical and Critical. 8vo

- Trial of Theodore Parker for the “Misdemeanor” of speech in Faneuil Hall against Kidnapping. 8vo

- Transactions Nat. Ass. for the Promotion of Social Science, for 1858

- Universe (The) no Desert, the Earth no Monopoly. Boston, 1855

- U.S. Agricultural Reports, 1862, ’64, ’65, ’67

- U.S. Statutes, 1789–1827. Sheep

- Van Buren, Martin. Life of Political Opinions of. Worn

- Vaughan, R. A. Hours with the Mystics. 2 vols

- Vestiges of Civilization. N.Y., 1851

- Vestiges of Creation. 18mo

- Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Numerous illustrations on wood. 8vo. London 1853

- Voltaire’s History of Charles the Twelfth

- Vulliet, M. Geography of Nature; or the World as It Is. Numerous illustrations. Boston, 1856.

- Wayland’s Elements of Moral Science

- ———. Elements of Political Economy

- ———. Apostolic Ministry. 16mo. flex.

- Wayland, F. University Sermons

- Warren, Sam’l. Intellectual and Moral Development of the Present Age. Thin, 12mo

- Waddington, Rev G. History of the Church from the Earliest Ages to the Reformation. 8vo

- Watsons’ Dictionary of Poetical Quotations

- Weale, Jno. Dictionary of Terms in Art, Architecture, Surveying, etc. Flexible, illust

- Webster and his Master Speeches. 2 vols

- Whewell’s, Wm., History of Inductive Sciences, from the Earliest Period. 2 vols London, 1857.

- ———. Novum Organum Renovatum

- ———. History of Scientific Ideas 2 vols. London, 1858

- What is Truth? London, 1856

- Whateley’s Elements of Rhetoric

- White, Rev J. Eighteen Christian Centuries.

- Whipple, E.P. Washington and the Revolution; an Oration. 16mo, flexible. Boston, 1850

- ———. Essays and Reviews. 2 vols

- ———. Literature and Life

- Wilkinson, J.J.G. The Human Body and its Connection with Man

- Wilks, W. The Half Century: Its History, Political and Social. London, 1853

- Wilson, Henry. History Anti-Slavery Measures of 37th and 38th Congress.

- Woolsey, T. D. Introduction to the Study of International Law

- Wyndham, Wm. and Wm. Huskisson. Select Speeches of. 8vo

- Youmans, E.L. Hand-Book of Household Science. Numerous Illustrations.

- Young, A.W. Citizen’s Manual of Government and Law. Half roan

- American State Papers: Public Lands, complete. 5 vols., Imperial 8vo, half Russia. Washington, 1834

- Stephen on Pleading. Notes by Heard. 8vo, sheep. Phila., 1867

- Kent’s Commentaries, 4 vols., 8vo, sheep

- Hilliard on Real Property. 2 vols., 8vo, N.Y., 1855.

- Walker’s Introduction to American Law. 8vo, sheep. Boston, 1860

- Parson’s Elements of Mercantile Law. 8vo, sheep. Boston 1862

- Wendell’s Blackstone’s Commentaries. 4 vols., 8vo, sheep. N.Y. 1854

- Huxley and Youmans’ Physiology and Hygiene. Numerous illustrations, new. N.Y., 1872.

- Cutter’s Anatomy, Physiology and Hygiene. 150 illust’s. Phila., 1871

- Hutchinson’s Physiology and Hygiene. Numerous illustrations. N.Y., 1873

- Kiddle’s New Elementary Astronomy. Illustrated, new. N.Y. 1871.

- Venable’s New School History of the U.S. Maps and illust’s. Cin’ti, 1872

Persons unable to attend the sale can have their orders to purchase executed FREE OF CHARGE, by limiting their prices and intrusting them to the Auctioneers, who will buy as much lower as possible. ALL BIDS SHOULD BE MADE SO MUCH PER VOLUME. BOOKS open for examination on Tuesday, the 7th inst., and up to time of sale.

Notes

John J. Duff, A. Lincoln: Prairie Lawyer (New York: Rinehart, 1960), 100.

Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 1:221–22.

David Herbert Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1948), 18–20, 237; Herndon to Weik, February 24, 1887, Herndon-Weik Collection, Library of Congress.

Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon, 53, and Henry B. Rankin, Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Putnam, 1916), 120.

George Alfred Townsend, The Real Life of Abraham Lincoln: A Talk with Mr. Herndon, His Late Law Partner (New York: Publication Office, Bible House, 1867), 4–5.

The author thanks Dr. Wayne C. Temple for first bringing “Herndon’s Auction List” to his attention, and Dr. James Cornelius, curator of the Lincoln Collection at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, and Dr. John Hoffmann, curator of the Illinois history and Lincoln collections of the University of Illinois Library at Champaign-Urbana, for their generous assistance with the research. Herndon’s Auction List. Broadside. Sale of Herndon’s Books in Cincinnati by W. O. Davie & Co., January 10 and 11, 1873. Printed Ephemera Collection, Library of Congress, Portfolio 345, no. 20. I am greatly indebted to Dr. Wayne C. Temple for providing me with a photocopy of the original document.

Herndon to Remsburg, before 1893, in John E. Remsburg, Abraham Lincoln: Was He a Christian? (New York: Truth Seeker, 1893), 114–15.

Readers of Allen C. Guelzo’s excellent Abraham Lincoln as a Man of Ideas (19) might be misled into thinking that Lincoln was the main agent for the purchase of certain highly speculative philosophical works that were far more likely to appeal to Herndon than to Lincoln: “Herndon remembered that the Lincoln-Herndon law office filled up . . . with volumes [by, among others] . . . Thomas Carlyle, . . . the French “common-sense” realist Victor Cousin and his English counterpart, Sir William Hamilton, the biblical criticism of D. F. Strauss and Ernst Renan, . . . Feuerbach, . . . Buckle, . . . [and] Spencer.”

Robert Bray, “What Abraham Lincoln Read—An Evaluative and Annotated List,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 28 (2007): 28–81.

Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, eds., Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), 566, 606–7.

Wayne C. Temple, “Herndon on Lincoln: An Unknown Interview with a List of Books in the Lincoln & Herndon Law Office,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 98 (Spring–Summer 2005): 38–39.

A lack of orderliness may be assumed from the observation of a journalist visiting the law office in 1867 who saw on the bookshelf only volume three of Macaulay’s History of England, which was probably from the five-volume edition published in Philadelphia in 1849 by E. H. Butler & Co.; six years later Herndon included only volumes one and two on his auction list. Temple, “Herndon on Lincoln,” 45.

William E. Barton, Abraham Lincoln and His Books (Chicago: Marshall Field, 1920), 12, mentions specifically Worcester’s Ancient and Modern History, which is not on the auction list.

Rankin, Personal Recollections, 123; John Fort Newton, Lincoln and Herndon (Cedar Rapids, Iowa: Torch Press, 1910), 254.

William H. Herndon and Jesse Weik, Herndon’s Life of Lincoln (1889; ed. Paul M. Angle, Cleveland: World, 1942), 477.

Lincoln to Herndon, July 10, 1848, in Roy P. Basler et al., eds. Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick: N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953–1955), 1:497–98.

Lincoln was allegedly called a “book-worm” by “his fellow Congressmen”, according to a 1909 source found by Douglas L. Wilson, Lincoln Before Washington: New Perspectives on the Illinois Years (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 3.

Emanuel Hertz, ed. The Hidden Lincoln: From the Letters and Papers of William H. Herndon (New York: Viking Press, 1938), 172.

James A. Secord, Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 3. The auction list mentions “Vestiges of Creation. 18mo” followed by “Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Numerous illustrations on wood. 8vo. London 1853.”

Herndon and Weik, Herndon’s Life of Lincoln, 353–54, and Herndon to Remsburg, before 1893, Remsburg, Was He a Christian? 135.

Herndon to Remsburg, Was He a Christian? Herndon, while not quoting, closely echoed a phrase in Lincoln’s lecture on “Discoveries and Inventions”: “observation, reflection and experiment.” Collected Works, 3:358.

The auction list mentions only the 1854 volume of the Annual, so perhaps Lincoln’s own set was not left in the office to become part of Herndon’s collection; or perhaps it was, and the 1854 volume was merely a duplicate Herndon was willing to sell off.

Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, eds., Herndon’s Informants (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 350.

Wayne C. Temple, Lincoln’s Connections with the Illinois & Michigan Canal, His Return from Congress in ’48, and his Invention (Springfield: Illinois Bell, 1986), 59–63; Jason Emerson, Lincoln the Inventor (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009), 15–18.

After the entry mentioning ten volumes of Patent Office Reports, the next item refers to sixty-two volumes of “Public Documents,” including “Patent Office Reports.”

Wayne C. Temple, “Lincoln the Lecturer, Part 1,” Lincoln Herald 101, no. 3 (1999): 94–110; “Lincoln the Lecturer, Part 2,” ibid., no. 4 (1999): 146–63; James Lander, Lincoln and Darwin: Shared Visions of Race, Science and Religion (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2010).

Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon, 15; Catherine H. Dall, “Pioneering,” Atlantic Monthly 19, no. 114 (April 1867): 404.

Bray, “What Abraham Lincoln Read,” 55 n, 86. The same book appears in a photograph labeled “Books From Abraham Lincoln’s Library,” an illustration in Frederick Trevor Hill, Lincoln the Lawyer (New York: Century, 1906), 15. Hitchcock also published Elementary Geology (3d ed., 1844), which is not in Herndon’s auction list; however, a journalist copying down titles of books in Herndon’s office in 1867 recorded “Hitchcock’s Elements of Zoology,” which is unidentifiable and probably a note-reading error. Temple, “Herndon on Lincoln,” 46.

John T. Stuart quoted in James Q. Howard, May 1860, “Biographical Notes,” Series 1, General Correspondence, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, 15.

Bliss to Herndon, January 29, 1867, in Wilson and Davis, Herndon’s Informants, 552.

Katherine B. Menz, Historic Furnishings Report, Lincoln Home, National Historic Site, Illinois, (Harpers Ferry: National Park Service, 1983), 102–3.

A. R. Crook, A History of the Illinois State Museum of Natural History (Springfield, Ill.: Phillips Bros., 1907), 9–10; Sunderine Temple and Wayne C. Temple, Illinois’ Fifth Capitol: The House That Lincoln Built and Caused to be Re-Built (1837–1865) (Springfield: Phillips Brothers, 1988), 151–52.

Maus v. Worthing [Worthen], 4 Ill. (3 Scam.) 26, 26 (1841), discussed in Mark E. Steiner, An Honest Calling: The Law Practice of Abraham Lincoln (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press), 135–36, n245.

General Catalogue of Oberlin College 1833–1908 (Oberlin, Ohio: O. S. Hubbell Printing, 1909), 613; General Catalogue of the Theological Seminary, Andover, Massachusetts, 1808–1908 (Boston: Thomas Todd, Printer, 1908), 274; History of Mercer County Together with Biographical Matter, Statistics, etc. (Chicago: H.H. Hill, 1882), 222, 361–62; John William McLure, “History of the Illinois State Geological Survey, 1851–1875” (master’s thesis, University of Illinois, 1962), 124–36.

Theodore C. Pease and James G. Randall, eds., The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1925–31), 1:290 (June 15, 1857). See also, 1:404, 507.

McLure, “History of the Illinois State Geological Survey,” 130, states that “Lincoln and Leonard Swett went to the governor’s mansion and attempted to get Bissell to sign the bill,” but no supporting evidence is provided or has yet been found.

R. P. Stevens to Lincoln, June 24, 1858, Abraham Lincoln Papers. Some of McChesney’s correspondence with Stevens and with Browning can be found in the Joseph H. McChesney Papers in the Illinois history and Lincoln collections, University of Illinois at Champaign–Urbana, and the Joseph H. McChesney Papers, Special Collections, Knox College.

John M. Clarke, James Hall of Albany (New York: Arno, 1978), 283–86. In 1859 McChesney proposed that Knox College purchase 14,000 of his specimens of minerals and fossils, which he said were worth at least $10,000, though he asked for only $3,000. Joseph H. McChesney Papers, Special Collections, Knox College.