Interpreting the Lincoln Memorial Landscape at Hodgenville, Kentucky: The Howell Family Heritage

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The Lincoln Landscape

Professionals and amateurs alike have helped save and define the growing number of sites deemed historic since 1850, when New York state's purchase of the Hasbrouck House in Newburgh marked the first generally accepted preservation success in the United States. [1] The proliferation of historic sites, bolstered by increased budgets, widespread publicity, expanding tourism, and increased specialization of skills—archaeology, architecture, building trades, and law to name a few—have contributed to what observers now refer to as a historic preservation movement. [2] Professionals Page [End Page 63] developed well-defined codes identifying acceptable and unacceptable practice, created specialized technologies for their work, and embraced formal education with accredited degrees to empower their work at potentially nationally and internationally significant locations. Yet amateurs, people simply inspired, whether volunteers in the interpretive programs of a site or neighbors coalescing in a campaign to save the intangible quality of life in an older section of town, remained a wellspring of energy and commitment. Such laymen also gave rise to historic preservation in America.

Abraham Lincoln's reputation has benefited considerably from the historic sites associated with his life and the memorials to him. Indeed, Lincoln has taken on mythic proportions and achieved global celebrity in part because of the sites that tourists visit for various reasons, including pilgrimage. Lincoln sites not only passively receive tourists, but visitors come away with perceptions and memorabilia that add to the immortality of the deceased wherever and whenever they interact with other people afterward. Visiting the Lincoln sites, though they are not exceptional in this respect, is very much a performed activity.

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site outside Hodgenville, Kentucky, not only ranks among the most visited of publicly administered sites, it has enjoyed the Howell family's unusual private efforts to extend the site's interpretation. Since 1928 three generations of Howells have maintained and managed the Nancy Lincoln Inn, contiguous to the birthplace historic site, which is managed by the National Park Service. The Howells variously operated a restaurant, museum, gift shop, and four overnight cabins on the property.

Several sources trace the transformation between 1895 and 1916 of the Lincoln birthplace from a cabin of uncertain provenance on private land to a national park—it was only the fourth historic house deemed suitable for federal ownership—and touch on the park service's determination to distinguish between fact and fiction Page [End Page 64] at the site.[3] The following provides the most extensive public account of the Howell family's ancillary role at the site.[4] The Howells have functioned as unofficial stewards of this earliest Lincoln shrine, which alone merits attention. However, they combined their self-assigned mission with a tourist strategy for local economic development centered on the site. This paper aims principally at placing on record a reliable account of the Howells's contribution. Their total work also adds a small installment of Lincolniana to the new field of tourism history that bridges a relationship between an isolated case study and issues of interest to academic historians.[5] Page [End Page 65]

Spiritual and material interests have often combined or rivaled for the policy and popular perception at historic sites since the nineteenth century. The Lincoln birthplace has been no exception. Reverence for Lincoln as well as commercial enterprise motivated preservation efforts for the birthplace and its site from the inception of interest in 1894. The twin motives initially were at odds. Major S. P. Cross's unrealized ambition in 1894 to purchase the site, without any log cabin interpreted as the house in which Lincoln was born, aimed to achieve the same respected rank as the last homes of George Washington and Andrew Jackson. Alfred D. Dennett, a restaurateur and benefactor of religious missions, purchased the farm including the birthplace site in 1895, and his agent claimed that Dennett ordered him to purchase the original cabin for relocation to the birthplace. Planning to build a hotel on the site to recoup his investment, Dennett's initial audience was a Grand Army of the Republic reunion in nearby Louisville in 1895. Less than one hundred of the five thousand to fifteen thousand attending veterans visited the site, complaining of their distaste for Dennett's obviously commercial ends, including a high admission price and his agent's railroad fare. The site further descended into controversy when the birthplace cabin's repeated dismantling and transportation to various exhibitions and storage sites cast its authenticity into doubt. Dennett eventually lost ownership in a public auction to pay his creditors.

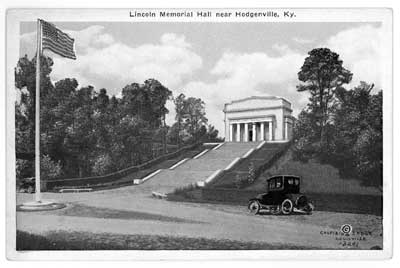

The Lincoln Farm Association, guided by Richard Lloyd Jones, the editor of the nationally circulated Collier's Weekly magazine, restored the site to respectability in well-chronicled steps begun in 1904 when he purchased the site and campaigned to fund a permanent memorial. In 1909 the Lincoln Farm Association dedicated the site in a well-publicized ceremony, followed two years later by a similar dedication of a building in the majestic Beaux Arts style to house the log cabin birthplace. The association also undertook a serious investigation of the cabin's authenticity—satisfying itself that the cabin was Lincoln's birthplace—and, in 1916, culminated its aim of renaissance for the site when federal authorities, appropriate to the status of a national symbol, assumed ownership and management of the site. [6]

Tourists arriving by automobile swelled visitation in the 1920s, presenting new opportunities of interpretation but problems of Page [End Page 66] management as well. Many of the more than eight thousand automobiles annually entered the park through private fields rather than the inadequately maintained federal entrance, and travellers' picnic refuse provoked the site staff to complaints similar to private landowners about uninvited auto travelers. Counting more than twenty thousand visitors in 1927, administrators determined to rearrange the site's landscape to better manage its growing traffic.[7]

Volume was not the only problem. Businesspeople conveniently situated services to the automobile-borne arrivals. Several families on adjacent farms, presented with opportunities to supplement the income from their relatively poor soil, sold souvenirs. A gasoline station and a rooming house also opened.[8] The Nancy Lincoln Inn and cabins, however, became the most enduring of those tourist services and a historic site in its own right. The inn and cabins were entered into the National Register of Historic Places in 1991. [9]

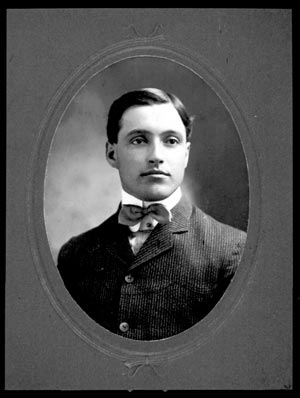

In 1928 James Richard Howell opened the inn and cabins. He had wanted to purchase the property contiguous with the park at an earlier time to develop his venture but was forced to wait until the property became available in 1928. A descendant of Howells who came to Kentucky before statehood, "Jim," as he was familiar to most, was a well-respected businessman and, in his grandson's words, "a bit of a mover and shaker in LaRue County for a number of years."[10] Jim Howell variously served as a city councilman, school-board member, mayor of Hodgenville, LaRue County sheriff, representative in the state legislature (1912–14), and United States marshal (during World War I). [11] In the late 1920s or early 1930s, at rural Malt, an open-countryside community on Otter Creek, he and his brother assumed operation of their father's roller mill, the state's second largest over-shot wheel, and a source of family pride. [12] In 1928 Jim Page [End Page 67] bought his father's roller mill in Hodgenville, but the inn and cabins he opened that year were more than a business enterprise.

Howell was a friend of Louis A. Warren, a Christian minister and renown Lincoln scholar of the era. Warren's curiosity about Lincoln's genealogy and birthplace began in Hodgenville in 1919 when he became editor of the LaRue County Herald. Thirsting for a factual knowledge about the earliest origins of the man he tended to deify, Warren painstakingly and methodically pursued archival evidence about Lincoln in more than thirty Kentucky county courthouses while living in Hodgenville and nearby Bardstown, to which he moved in 1921. According to his own account, whereas fewer than a dozen "duly authorized public documents" were available at the beginning of his research, his discovery of "550 court entries bearing the name of either Lincoln or Hanks," "1000 other documents ... about the environment in which the Lincolns moved, or record the activities of the cognate families ...," and "military certificates, tombstone inscriptions, church and school record books, personal papers, and the like" enabled him to publish Lincoln's Parentage and Childhood: A History of the Kentucky Lincolns Supported by Documentary Evidence in 1926.[13] The Century Company published Warren's book, and his elevated scholarly standing led the Lincoln National Life Insurance Company, in hopes of an auspicious beginning, to invite Warren as founder of the Lincoln Historical Research Foundation.[14]

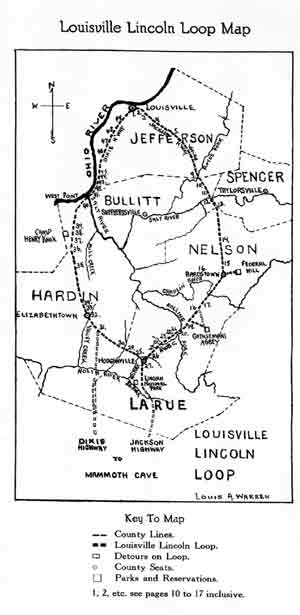

Warren also embraced the use of the automobile. The nation's small group of historic preservationists included many who perceived such automobile services as parking lots and service stations as threats to buildings deserving preservation. Still, they did not wish to turn away visitors who were touring sites by automobile.[15] Warren strongly advocated auto tourism, seeing it as no threat to the Lincoln shrines. Indeed he viewed auto touring as benevolent. As he wrote in 1922 in a brochure "A Day's Tour 'In Old Kentucky,'" "the establishment of national highways for motor-driven cars has done much to create an interest in places of historical import, hitherto inaccessible to the tourist. Many points remote from the general lines of travel by rail, have now become centers of Page [End Page 69] interest, because they are easily reached over some hard road." [16] No railroad passes through Hodgenville to this day. The Jackson and Dixie highways, two of the privately named and built auto roads preceding the creation of the federal highway system in 1926, were of special interest to Warren because five homes associated with the Lincoln family could be reached on a day's tour, the "Louisville Lincoln Loop," as he promoted it. "With at least a dozen other places of historical importance on this loop, there should be no challenge to the claim that it is the most interesting one day's automobile trip west of the Alleghany [sic] Mountains."[17] Kentucky's State Highway Commission for the period ending June 30, 1925, reported that no more than a mile or two of the loop from Louisville was "poorly surfaced" and that automobilists could travel nearly the entire length of the Jackson and Dixie highways from Louisville southward or Nashville, Tennessee, northward on an alignment of "good surfacing" or "under construction." The "poor surfacing" exceptions to the statewide traverse were approximately eleven miles on the Jackson alignment and twelve miles on the Dixie Highway. According to the same exultant report including those two highways, more privately named highways were "now finished, hard surfaced, and passable ... than can be boasted on its share of the national highways by any neighboring state of the south." [18]

The state highway authority had helped make feasible Howell's roadside services. The physical relationship of those services to the Lincoln memorial testified to the nature of Howell's intentions. A man of considerable respectability in Hodgenville and its environs, Howell designed a historical and spiritual complement to the Lincoln memorial. He certainly wanted to avoid the crass manipulation of his property for private gain, which the federal park authorities abhorred in the automobile services near the site. Howell was a businessman and hoped for visitors, but he didn't expect that his contributions would make the area into a rich tourist mecca. Howell chose materials, studied intended uses, and sited his buildings to support the neighboring memorial. Howell sought out and had the Nancy Lincoln Inn and four cabins constructed in 1928 of locally available, insect-resistant chestnut. A blight in the 1930s, Page [End Page 71] however, destroyed the nearby chestnut stands, making it a rare and coveted lumber within a few years. Flooring in the inn was red pine, which maintained an attractive and very durable finish. Red pine was not locally available, demonstrating Howell's intention to produce a high-quality building.[19] In 1930 Howell sought out Pleasant Skaggs, a farmer in Taylor County who was also a carpenter and stone mason, to craft a high-quality fireplace with mantel and outside chimney. Satisfactory completion demanded care and precision.[20] If any craftsmen were locally available to execute the project, they were obviously bypassed. Although the inn and cabins had a rustic appearance that Howell believed was sympathetic to the log cabin birthplace, their scarce materials and craftsmanship shortly rendered them something of architectural gems.

Uses at the inn included a restaurant and curio shop with historical memorabilia displayed in a comfortable ambiance. A federal Page [End Page 72] history of the site mentions that the inn was also a "dancing establishment," but no trace of it survives in the Howell family oral tradition.[21] Lunches and dinners were prepared for the convenience of memorial visitors, who needed to walk only several hundred feet from their car to get a meal rather than being forced back onto the highway in search of a restaurant. In good weather, picnic tables on the inn's porch provided a pleasant alternative to eating inside. Known better by locals than travelers, but open to both, was a picnic area Howell kept clear on a hill just west of the inn. [22] It perhaps replaced a pavilion the park managers had maintained at the memorial between 1929 and the early 1930s. [23] The joys of eating outside made Howell's a hospitable place. The inn's walls displayed memorabilia Howell collected as his interest in local history grew. A bloodied Confederate flag from the Battle of Perryville was his most cherished item.

Details helped clinch the place-specific ambiance of the business. One of the most popular curios sold at the inn was a miniature log Page [End Page 73] cabin modeled after the one enshrined in the memorial within view north, across the parking lot. Local whittlers, both men and women, crafted those miniatures that sold for a few cents, and they have since become coveted examples of folk craft. The souvenirs may have been sold as early as 1917 at a museum shop to the rear of the memorial run by a benevolent organization—the Ladies' Lincoln League—and possibly later by the Womens' Clubs of Hodgenville in a shop inside the memorial. The museum shop was banished from the memorial, probably in the early 1930s as part of the National Park Service's new nationwide policy of no commercial ventures on the grounds it administered.[24] In the early 1930s the Nancy Lincoln Inn became the primary outlet for the miniature log cabins, and the inn's porch occasionally functioned as a stage for the craftsmen at work. Other businesses along the highway outside the memorial also sold some of the miniatures. [25] From local people, Howell also purchased handmade rugs and sold them at the inn.[26] Especially during the depression of the 1930s, the local craftspeople supplying Howell's inn welcomed the supplemental income from the cabins and the rugs. Howell's motives combined genuine pleasure in providing a modicum of economic relief to the craftspeople whom he considered his neighbors and carrying items that made his shop unique.

John Urry has explained the "special gaze" that distinguishes tourist sites like the Lincoln Memorial from other settings. By contrasting tourist settings with non-tourist settings, particularly home and work places, tourists harbor unspoken expectations of their visit. Urry characterized fulfilled expectations as "daydreaming," "fantasy," and "intense pleasures" and underscored the visual sense's primary role in cueing the expectations.[27] Louis Warren, who influenced Howell's thinking, acknowledged that he "made frequent visits to the Lincoln Farm and often sat before the cabin dreaming of the days when Thomas Lincoln [Abraham Lincoln's father] was Page [End Page 74] lord of the surrounding acres ..." [28] Tourists, Urry wrote, sought and hoped to suspend themselves in the flux of time by literally stepping onto distinctive landscapes. Once such landscapes were successfully produced, the tourist industry attempted to permanently position those landscapes outside the flux of time through memorabilia—principally postcards, films, models, and photographs. With those, producers or tourists could consequently conjure the tourist gaze upon demand. [29] Such are the strategies of tourism. "Tourism," declares John Jakle, "is a state of mind." [30]

The capstone of Howell's produced landscape on the boundary of the Lincoln Memorial was the overnight lodging he rented immediately east of the inn. Space in front of each of the four cabins and on their front porches could amply seat the lodgers. Howell's sincere reverence for Abraham Lincoln and the memorial took fitting form in the landscape that lodgers saw immediately before them—the sinking springs at ground level and the architecturally enshrined birthplace on the hillside elevation. Legend had it that Page [End Page 75] the sinking spring near the southwest corner of the stairs to the memorial supplied the infant Lincoln's water in the two-and-one-half years he lived at the site. Whereas the spring can be interpreted to symbolize the human Lincoln—an infant requiring the basic resource of water everyone needs for life—the memorial surmounting a hill and accessed by the fifty-six stairs—one for each year of his life—can suggest his ascension to historical prominence and immortality. The totality produces a compelling site to the predisposed tourist. A historic timeline was incarnate in the landscape. Howell did not verbalize this rationale. The purpose seemed obvious: "the idea being—I am sure—my grandfather had of experiencing tourists from out of state perhaps coming in and getting the feel of spending the night in a cabin along the lines of which Lincoln would have himself lived in as a child only a few hundred feet away from the actual site that he was born." [31] A warm host at his restaurant and manager of the inn and cabins, Howell, again in his grandson's words, "loved to sit on the front porch of the inn himself and greet the many people, some of which were local, [and from] all across the United States. They would get to know him and bring friends back to meet him because he loved to talk about the favorite place on this earth, and that was the Nancy Lincoln Inn." [32] The gregarious Howell instinctively understood what Urry elucidated as the tourist gaze.

Howell—the private citizen, businessman, and Lincoln enthusiast—and the memorial's managers, who are representative of the incipient professional wing of the historic preservation movement, differed on the issues that the tourist gaze raised. No evidence exists of personal disagreements between Howell and the memorial's managers. In fact, Howell offered property to the park to help arrange a new entrance. [33] Yet, their visions of landscape spoke of two distinct viewpoints. Howell had contrived a landscape of hospitality, valuing foremost tourist comfort, entertainment, and simulated historical experience. The memorial managers' own version of the tourist gaze focused on maintenance and landscape appearance. A drainage project, a new restroom's plumbing, and repairs on the roof of the memorial building comprised the accomplishments during the Depression-era's poor budgets. Long-range planning, however, anticipated an improved park entrance, return of the sinking Page [End Page 76] spring to a natural setting from a "walled in artificial place," as a park service memorandum characterized it, and removal of much of the flagstone and concrete walks, courts, and many buildings.[34] Although the government's intent to restore the ensemble's look to the era of Lincoln's boyhood went unrealized in the 1930s due to insufficient funding, vegetation (including inexpensive red cedars) was planted to block the sight lines between the memorial and the Nancy Lincoln Inn and cabins. A National Park Service inspection in February 1934 explained that notwithstanding the inn's sale of tasteful souvenirs, Howell's inn and cabins represented an unacceptable adjacent commercialization.[35] The park service desired a tourist gaze of formal propriety and a historical landscape reconstructed with the greatest feasible accuracy.

The Howells shifted their focus somewhat after the mid-1940s. Jim closed the cabins in 1946. It is uncertain why, but Carl Howell Jr. speculated that it was because his grandfather did not live on the site, had other business interests, and had become more Page [End Page 77] secure financially. He is sure competitors with more up-to-date lodging in the vicinity did not force his grandfather out of the lodging adjunct at his inn. [36] By the 1940s, might the maturation of the vegetative screen planted in the 1930s have blocked the sight line to the memorial that attracted travelers to overnight residence? He did retain the cabins. Their exterior helped sustain the rustic scene while simultaneously warehousing commodities for sale at the inn.[37] Jim Howell certainly continued the distinctive ambience he inaugurated at the inn he managed on a daily basis. His business interests included the LaRue Federal Savings and Loan Association, for which he was a director, but in the late-1940s he sold the Hodgenville Roller Mills. [38] When he died in 1957, his son Carl, who had co-owned the inn with him for many years, assumed daily management. Carl avidly collected historical artifacts, purchasing a greater number and more expensive items than his father had, for display in cases at the inn. "People not only thought of the Nancy Lincoln Inn as a souvenir shop but as a museum," Carl Howell Jr. recalls. [39] Although the Howells apparently never advertised their site, they promoted tourist awareness of the local Lincoln sites. Jim encouraged his sister, Hattie, and her husband, Chester Howard, to acquire and manage another Lincoln site, the boyhood home (1811–1817) at the Knob Creek Farm, which they did in 1931. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, while Carl was busy as the executive vice-president and managing officer of LaRue Federal Savings and Loan Association in Hodgenville, he also functioned as the town's one-man chamber of commerce. The post office delivered to him all letters addressed to the chamber, and his response to each one's individual interests Page [End Page 78] also customarily enclosed information and postcards about the area's Lincoln sites. [40]

In the last half century, tourists at the memorial could gaze upon two perceptions of Lincoln's first home. Federal managers "transformed a few acres of rolling farm country of central Kentucky into a formal secular shrine complete with a classical temple and a carefully manicured landscape," in the words of an official report in 2001.[41] When the National Park Service added hiking trails and picnic facilities, in 1970, Carl Howell closed the picnic area west of his inn. In 1975 he built a single-story brick home that blends comfortably with the scene. After he died in 1983, his wife, until her death in 1993, and then his daughter, Pamela Sue Howell, owned the inn, according to a life estate.[42] Carl Howell Jr., an attorney and former FBI agent who practiced law with his father, leased the property from his sister in 2001. A collector and student of Lincoln who delivered the keynote address when the National Park Service took possession of the Knob Creek Farm on February 12, 2002, Carl Howell Jr. has spent a considerable sum to refurbish the inn and stock it with high-quality souvenirs that include some locally made goods. He hopes to reopen the cabins and, if he does, to advertise in brochures on a website: "experience a day and an evening in a cabin similar if not nearly identical to the cabin in which Lincoln was born and lived for the first two and one-half years of his life."[43] He persists in the best tradition of the Howell heritage.

Historic sites are very much landscapes of production and consumption. Owners and managers script interpretations and arrange the setting to convey an impression and supply information. Visitors come from diverse backgrounds and enter with wide-ranging expectations. Thus, producers and consumers alike share in high personal and societal stakes, especially at the celebrated Lincoln sites. Historians can contribute an understanding of how tourism has worked at various times only after carefully chronicling the exchange from site to site over time. At the Abraham Lincoln Page [End Page 79] Birthplace, management changed from amateur to professional while a family on contiguous property looked on as if tourists themselves and strove as amateurs to provide an authentic experience to their customers and the memorial's tourists.

The author wishes to thank Carl Howell Jr. for the courtesy of his interview, access to family archives, and several informative letters. Kenneth E. Apschnikat, Superintendent, Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site, generously supplied public materials from his site files and also deserves the author's thanks. Page [End Page 80]

Notes

-

Charles B. Hosmer Jr., Presence of the

Past: A History of the Preservation Movement in the United States

before Williamsburg (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1965), 35.

-

Professionalism became a consideration

beginning in the 1920s, but full-time professional preservationists

remained uncommon until the late twentieth century. Architects, who

with few exceptions dedicated the years 1945 to 1965 to modernism,

which viewed past styles dimly, became perhaps the most vigorous

proponents for professionalism in historic preservation by the

1970s. See Stephen W. Jacobs, "The Education of Architectural

Preservation Specialists in the United States," in Preservation

and Conservation: Principles and Practices, ed. Sharon Timmons

(Washington, D. C.: Preservation Press, 1976), 459. Thereafter,

debate began over the degree and the ways in which professionalism

could best inform the maturing historic preservation movement. For

an example of an early voice insistent upon the benefits to

preservation of specialist contractors and architectural firms, see

William J. Murtagh, "Professionalism," in Preservation: Toward

an Ethic in the 1980s (Washington, D. C.: Preservation Press,

1980), 157.

A decade later, the

professional-amateur dichotomy had become a major theme in the

preservation dialogue. For example, the preservation conference

jointly convened by the National Council for Preservation

Education, the National Park Service, and the Center for Graduate

and Continuing Studies at Goucher College in March 1997 included

presentations that were either fully dedicated to the

professional-amateur theme or treated it tangentially. Especially

see Frits Pannekoek, "The Rise of a Heritage Priesthood,"

Preservation Of What for Whom? A Critical Look at Historical

Significance, ed. Michael A. Tomlan (Ithaca, New York: National

Council for Preservation Education, 1998), 29–36; Stephen C.

Gordon, "Historical Significance in an Entertainment Oriented

Society," Ibid., 58; Howard L. Green, "The Social Construction of

Historical Significance," Ibid., 94.

-

Hosmer, Presence of the Past,

141–46; Charles B. Hosmer, Preservation Comes of Age: From

Williamsburg to the National Trust, 1925–1949

(Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1981), 2:

929–30; Gloria Peterson, An Administrative History of

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Sites, Hodgenville,

Kentucky, National Park Service, U. S. Department of Interior,

September 20, 1968, 16–39; Robert W. Blythe, Maureen Carroll,

and Steven H. Moffson, revised and updated by Brian F. Coffey,

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site: Historic

Resource Report," National Park Service, U. S. Department of

the Interior, November 2001, 27–34.

-

Information here follows from several sources.

"Gray literature" includes a brief summary of the Howell-associated

sites in the National Register of Historic Places nomination form,

short passages in two National Park Service reports on the Abraham

Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site, and periodic reports on

Kentucky's early highway development. The author's interview of

(May 14, 2002, in Hodgenville) and subsequent correspondence (June

7 and June 13, 2002) with Carl Howell Jr., the family's

third-generation spokesperson dedicated to the Lincoln birthplace,

are the largest sources of evidence for the following account.

Pamela Sue Howell, Carl's sister, who holds the Nancy Lincoln Inn

in a life estate, was not interviewed. Carl shared the Howell

family archives containing some primary documents of his ancestors'

work, none declaring their intentions with the Nancy Lincoln Inn

and cabins, and nothing published, despite Carl Howell Jr.'s

exceptional family role as a serious writer and speaker on his

locale's history. See Carl Howell and Don Waters, Images of

America: Hardin and LaRue Counties 1880–1930 (Charleston,

S.C.: Arcadia Press, 1998); Carl Howell and Dixie Hibbs, South

Central Kentucky: Adair, Barren, Green, Hart, and Taylor

Counties (Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Press, 2001). Among

Howell's more prominent speeches, see his Keynote Address at the

Lincoln Birthday Celebration Luncheon, February 12, 2002, preceding

the deed transfer of the Lincoln Boyhood Home at Knob Creek to the

National Park Service; copy in author's possession. Modesty

notwithstanding, Carl Howell Jr.'s precise responses to questions

about his family's strongly conveyed memory about work for the

birthplace, including his own recollections of his grandfather who

died when Carl Howell Jr. was fifteen years old, make this key

interview a reliable source.

-

For example, see John F. Sears, Sacred

Places: American Tourist Attractions in the Nineteenth Century

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); Hal K. Rothman,

Devil's Bargains: Tourism in the Twentieth-Century American

West (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1998); Marguerite

S. Shaffer, See America First: Tourism and National Identity,

1880–1940 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution

Press, 2001).

-

Peterson, "Administrative History,"

16–39 passim; Blythe et al., Abraham Lincoln

Birthplace, 27–34 passim.

-

Peterson, "Administrative History," 44; Blythe

et al., Abraham Lincoln Birthplace, 39.

-

Blythe et al., Abraham Lincoln

Birthplace, 39; Peterson, "Administrative History," 51.

-

"Larue County Multiple Resource Area,"

National Register of Historic Places, November 19, 1990. The area

was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on January

10, 1991. Larue is the spelling that appears to be favored

by the federal government, although LaRue is favored by

state sources.

-

Howell interview.

-

"J. R. Howell, Hodgenville, Dies at Home,"

Louisville Courier Journal, July 16, 1957; "J. R. Howell,

78, Former Mayor, Dies Suddenly," LaRue County Herald News.

Carl Howell Jr. furnished both obituaries.

-

Howell and Waters, Images, 70; Howell

interview.

-

Louis Austin Warren, Lincoln's Parentage

and Childhood: A History of the Kentucky Lincoln Supported by

Documentary Evidence (New York: Century, 1926), vii–viii.

-

Mark E. Neely Jr., The Abraham Lincoln

Encyclopedia (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1982), 195.

-

Hosmer, Preservation, 1:2.

-

Louis A. Warren, "Louisville Lincoln Loop: A

Day's Tour in 'Old Kentucky,'" Louisville: Standard Printing, 1922,

7.

-

Ibid.

-

Seventh Biennial Report of the State

Highway Commission, Commonwealth of Kentucky, For Biennial Period

Ending, June 30, 1925, 14.

-

Howell interview.

-

Gene Perkins, "Building the Stone Chimney at

Nancy Lincoln Inn," The Kentucky Explorer, September 1998,

50–51.

-

Peterson, "Administrative History," 51.

-

Howell interview.

-

Peterson, "Administrative History," 53, 56.

-

For the history of the Lincoln log cabin

miniatures, see Robert Cogswell, "Lincoln's Cabin and Larue County

Carvers," Back Home (January/February 1984): 4–6; for

the assertion of the sale inside the memorial since 1917, see 5.

See Peterson, "Administrative History," 53, for the opening of a

museum shop inside the memorial in 1926, when the author of this

article offers that the miniature cabins known from Cogswell,

"Lincoln's Cabin," were sold.

-

Cogswell, "Lincoln's Cabin," 5.

-

Howell interview.

-

John Urry, The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and

Travel in Contemporary Societies (London: Sage, 1990), 3.

-

Warren, Lincoln's Parentage, 90.

-

Urry, The Tourist Gaze, 2–4.

-

John A. Jakle, The Tourist: Travel in

Twentieth-Century North America (Lincoln: University of

Nebraska Press, 1985), 1.

-

Howell interview.

-

Ibid.

-

Peterson, "Administrative History," 58.

-

Ibid., 56; Blythe et al., Abraham Lincoln

Birthplace, 37.

-

Peterson, "Administrative History," 48, 56;

Blythe et al., Abraham Lincoln Birthplace, 38.

-

Carl Howell Jr. to author, June 13,

2002.

Hodgenville had no city directory

upon which to base a systematic survey of surviving motel owners.

The extent of Howell's competition is uncertain. Prudence Whitlow,

who with her husband Eugene, owned and managed (1957–1995)

the Lincoln Memorial Motel, an advertised occupant of a site on the

Lincoln Farm just north of the memorial on highway 31E, said that

the amount of lodging in the area was insufficient (Prudence

Whitlow, telephone interview with author, May 17, 2002). H. Tharp,

who built (1956) and sold the Lincoln Memorial motel to the

Whitlows, was uncertain what other lodgings were in business when

he opened the motel (H. Tharp, telephone interview with author, May

23, 2002).

-

Carl Howell Jr., letter to author, June 7,

2002.

-

"J. R. Howell, Hodgenville, Dies at Home";

"J. R. Howell, 78, Former Mayor, Dies Suddenly," 1.

-

Howell interview.

-

"Hodgenville Attorney Carl Howell, Sr.

dies," The LaRue County Herald News, January 13, 1983, 1;

Howell interview.

-

Blythe et al., Abraham Lincoln

Birthplace, 39.

-

Carl Howell Jr., letter, June 7, 2002.

-

Howell interview. For the most recent

Hodgenville newspaper account of Howell's restoration work and

future plans before this publication, see Robin Terry, "Historic

Inn shines after remodeling," The LaRue County Herald News,

July 31, 2002, 1A, 12A.