Lincoln Essay Contests, Lincoln Medals, and the Commercialization of Lincoln

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

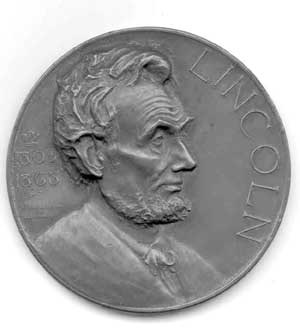

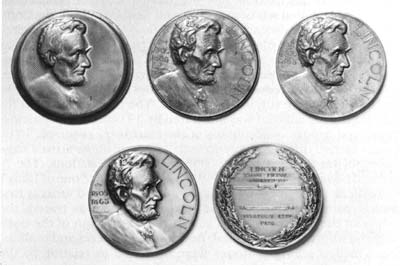

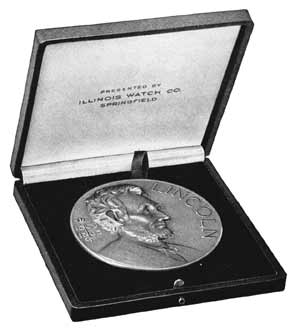

Few Lincoln collectibles turn up more often in the online auction market than a medallion of the president that the Illinois Watch Company of Springfield awarded, beginning in 1924, to the winner of the Lincoln Essay Contest in hundreds of high schools across the land. The face of the medal featured the image of Abraham Lincoln, while on the back was inscribed the name of the winner and date of the award—but not the name of the company ( Figure 1). Although the company's name had been included in the design of the medallion, it was expunged before the die was "sunk." Behind this change lay the artist's objection to the "advertising intent" of the watch company.[1] Other participants in the project were vexed and puzzled by this objection, but they eventually capitulated and the matter was forgotten. Yet it exemplifies the persistent belief that Lincoln has been over-commercialized.

The officers of the watch company, from its formation in 1870, had cherished their links to Lincoln. The first president was John T. Stuart, Lincoln's first law partner. In 1878, when the company was reorganized and renamed a final time, Jacob Bunn Sr., Lincoln's Page [End Page 36] banker,[2] became the president. When he died in 1897, Jacob Bunn Jr. took the helm.

The Bunns were not hesitant to associate the Illinois Watch Company and its pocket watches with Lincoln. In 1885, for example, the company sponsored Springfield, Ill. and Lincoln Souvenir, a portfolio of views of the town, including the Illinois Watch Company as well as the Lincoln landmarks. [3] Publications of the company routinely noted its proximity to the Lincoln Tomb. The foot of Monument Avenue, leading to the tomb in Oak Ridge Cemetery, rested on North Grand Avenue between First and Second streets; the company was located just blocks away on the northeast corner of Ninth and North Grand.

In 1907 the company introduced the "A. Lincoln" watch, the only watch it ever offered in three different sizes. The Lincoln watch was a great success, the company making 102,095 of them by 1928, when the Bunn family sold the enterprise to the Hamilton Watch Company. The A. Lincoln was a quality watch, most versions of which were nearly as expensive as the "Bunn Special." The prominence of the Bunn family, at least in Springfield, gave the company's top line of watches a certain cachet, without impinging upon the reputation of the Lincoln watch. [4] The Lincoln watches, regardless of size, remain collectible—and confusing. Because the signature A. Lincoln is engraved on the plate supporting the mechanism inside the watch, owners of the watch have frequently asked if it was at one time owned by the president. On one such occasion, his son, Robert Todd Lincoln, replied: "I can only say to you that I know nothing of such a watch as you describe. I think I know that Page [End Page 37]

The watch company distributed a medalet and chain, to serve as a watch fob for the Lincoln watch. On the front was a profile of the president, with his name and dates on the circumference. On the back, between an eagle and a Roman fasces—or bundle of rods—was written in capital letters, Illinois / Watch Company / Springfield / Makers of the / A. Lincoln / Watch. B. L. (Bela Lyon) Pratt, a leading Boston sculptor, designed the medalet, which was only about one and a quarter inches in diameter. The piece, although too small to be precisely rendered, was exceedingly popular. The watch company distributed hundreds of medalets both with and without its A. Lincoln watches.[6]

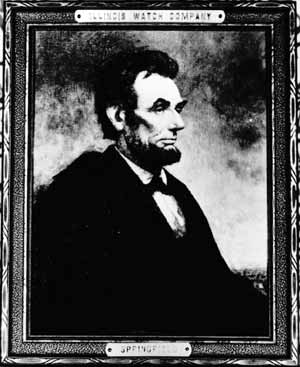

Beginning in 1913 the company also distributed a lithographic portrait of Lincoln on canvas. This print included an embossed, circular stamp in the lower right corner, with the words Illinois Watch Co. Springfield on the circumference and The Lincoln Watch in the Page [End Page 40] middle, all in capital letters. Placed in a gesso- and gilt-covered wood frame (about 11-by-14 inches), the print (about seven-by-ten inches) was produced by a lithographic process that made it appear as if it were an oil painting. The company sent its lithograph of Lincoln to dealers across the land for display next to Illinois watches, a promotional effort that reinforced the company's use of Lincoln. [7]

It was but a small step from Lincoln paraphernalia that advertised the A. Lincoln watch to an essay contest that would associate the Lincoln name and image with the company's entire stock. By implication, each watch was as reliable and as steadfast as the Savior of the Union, each timepiece as honest as Honest Abe. Moreover, the essay contest was a popular vehicle of civic education in the Progressive era, and no president more fully embodied the American creed than Lincoln.

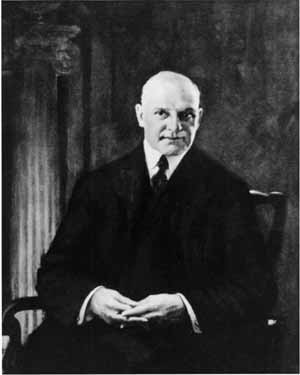

Jacob Bunn, president of the Illinois Watch Company, reflected this perspective in sending the following announcement to the high schools of the nation: "In view of this city being the former home and burial place of our martyred president, Abraham Lincoln, and desiring to encourage the study of his life and character, this company without selfish motives have [sic] been considering for some time the advisability of presenting annually, to a student in the senior class of each High School in the United States, a very handsome medal of Abraham Lincoln. The idea in mind," Bunn continued, "is to present the medal on Lincoln's birthday" to the student Page [End Page 41] at each high school who is deemed by a panel of at least three teachers to have written "the best short essay" on Lincoln (Figure 2).[8]

Bunn was already in touch with Walter C. Heath, president of the Whitehead & Hoag Company of Newark, New Jersey, which welcomed the opportunity to strike the medal for the essay contest. A leading maker of emblems and pins, buttons and badges, and other "advertising novelties," Whitehead & Hoag had by 1924 manufactured at least seventy-five medals, plaques, tokens, and coins in honor of Lincoln, including the Illinois Watch Company's medalet.[9]

On June 1, 1923, Heath of Whitehead & Hoag wrote Douglas Volk the first of many letters relating to Bunn's plans for the essay contest and the medal. An established artist, Volk had recently begun a series of Lincoln portraits that were based in part on the Lincoln life mask made by his father, Leonard Volk. Heath quoted Bunn's praise of a photograph of the Lincoln portrait that Douglas Volk had sold to the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, in 1922: "This picture is my ideal of a Lincoln portrait. I like it better than any I have ever seen ..." (Figure 3). [10]

Others who had viewed the portrait on exhibition were no less enthusiastic. "I can suggest no criticism of it at all," wrote Robert Lincoln. "Mr. Volk's father made from life the bust of my father which is absolutely perfect as a likeness. Mr. Douglas Volk's portrait shows him later in life and much changed in appearance, but Page [End Page 42]

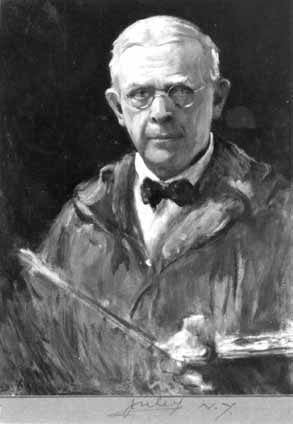

Douglas Volk first ventured into Lincoln portraiture in 1908, and that canvas, reworked in 1917, eventually found its way into the National Gallery of Art. It also achieved a kind of anonymous familiarity between 1954 and 1968, when it was featured on the regular four-cent U.S. postage stamp. During the 1920s, Volk became preoccupied with Lincoln portraits, beginning with the canvas that Bunn chose for the Illinois Watch Company award (Figure 4). To simplify the medal's design, however, Whitehead & Hoag could not use Volk's three-quarter-length portrait, which included Lincoln's hands and a background, but only a close-up view of Lincoln's head and shoulders. Furthermore, to reproduce the two-dimensional painting as a three-dimensional medal, Whitehead & Hoag required a sculptor capable of making a relief, the mold of which, much reduced, would define the die used in striking the medal.

Bunn suggested that Charles Keck be approached to make the model from which to cut the die. Keck was a prominent sculptor who had trained under Augustus Saint-Gaudens and had perfected his craft as a Rinehart scholar abroad. Bunn referred to him as a friend, and gave Heath the address of his studio in New York City.[12]

Volk, however, was not acquainted with Keck's work "in the medal line." He referred instead to other sculptors, including Daniel Chester French, Herbert Adams, Robert Aitken, and J. Massey Rhind. But as an alternative to Keck, Volk clearly preferred Charles Louis Hinton ( Figure 5 ). Volk recommended Hinton as "a talanted [sic] young sculptor," although his fifty-three-year-old friend was also a painter and book illustrator. In addition, Hinton, like the others, was an experienced medalist. But the important point was that Hinton "might be willing to collaborate" with Volk, while the other Page [End Page 45]

Hinton and Volk were close friends at the National Academy of Design in New York City. In 1923 Hinton was midway through a forty-seven-year career as an academy instructor, while Volk, who also taught there, was the institution's recording secretary. Hinton had named one of his sons Douglas, and later, during the Depression, Volk turned for help to Hinton, president of the Artists Fellowship, Inc. Hinton's father, like Volk's, had been a stonecutter in upstate New York, and the two academicians seemingly inherited a belief in permanent, classical standards, a commitment that they upheld against "the wild aberation [sic]" of younger artists "into the ugliness and incompetency of the modernistic."[14] Page [End Page 47]

In planning the Lincoln medal, Volk and Hinton thought in terms of the Beaux Arts style as shaped by American sculptors since the 1880s. By taking advantage of improvements in the technology of the reducing machine and by using the Janvier lathe to engrave a reduced copy of the medal directly into a steel die, the sculptors of the day created a rich legacy of artistic medals. On April 14, 1923, the National Sculpture Society, of which Hinton was the secretary, opened a major exhibition of sculpture and medals that took for granted that medallic art, "a difficult and worthy art," had become a branch of sculpture. The show included medals and sculpture by Adams, Aitken, French, and Hinton.[15]

By July 2, 1923, after Whitehead & Hoag had "interviewed and negotiated with several sculptors," Hinton was commissioned, as Volk wished. Hinton, as he developed the casts for the medallion, was eager to follow Volk's every suggestion. Convinced that the project would yield "the finest Lincoln medal ever made," Hinton found the work such a "heaven of delight" that he gave it ten-hour days and "hated night to come along to stop me."[16]

Hinton and Volk corresponded frequently as the project went forward. For more direct consultations, Volk visited Hinton in Bronxville, New York, and Hinton traveled to Hewnoaks, Volk's summer retreat near Center Lovell, Maine. "Mr. Hinton is here," Volk reported to Heath on July 27, "and working like a Trojan with excellent results. " Volk paid close attention to the details of Hinton's work, one indication of which is a page with their letters on which Hinton sketched Lincoln's right eye and right ear, and carefully identified the anatomical parts of each. [17]

Hinton, an "unassuming gentleman," was wholly deferential to Volk, "the master mind" of the project. What Hinton did not fully gauge, however, was Volk's insistence that Whitehead & Hoag, and even the Illinois Watch Company, defer to him on other questions that arose. Volk's obstinacy—for such it really was—nearly scuttled the whole project, even after Hinton had delivered the molds Page [End Page 48] to Newark on August 6, and the Whitehead & Hoag people had declared themselves "very much pleased" with the work.[18]

Volk was, first of all, a stickler about copyright. He agreed at the outset to accept $150 as "nominal" compensation for letting Whitehead & Hoag reproduce his portrait of Lincoln as a medallion, but he returned the check for this purpose when the memorandum on the back of it seemed to infringe upon his own copyright of the painting. Heath promptly sent Volk a second check, specifying that it gave Whitehead & Hoag the right to use the artist's work only on the medal, but Volk returned that, too, because he took issue with the wording on the design of the medal.[19]

The trouble was not the face of the piece, on which was stamped Lincoln in large capital letters, the years of his birth and death in smaller numerals, and, in minuscule size, in large and small caps, the names of the artist who drew the original (delineavit) and the sculptor who modeled it (sculpsit): Douglas.Volk. / Del. and Chas.L.Hinton. / Sc: (with the copyright symbol preceding Volk's name).[20] What bothered Volk was the back of the medal. The words Lincoln / Essay Medal / Awarded to (all in capital letters) were followed by spaces (set off by two ribbons) on which the winner's name and date of the award were to be inscribed. To this was added in Whitehead & Hoag's design: From the Illinois Watch Co.

Such wording was unacceptable to Volk. It created the impression that the medal was a mere advertisement for the company. It contradicted Bunn's announcement of the contest in which he assured high-school officials that the company's sponsorship was "without selfish motives." As Volk saw it, the proposed medal would be "robbed of dignity if it bore the name of any firm as donor." Volk had accepted a "nominal" payment for use of his painting in light of the company's apparently "lofty and patriotic" intentions. Had he realized that a mere "advertising idea" lay behind the medal, "no price would tempt me to use the head of Lincoln in this way." Hinton, ever compliant, wrote Volk that his stand against commercializing Lincoln was "the only right one," for "it does seem awful to use Lincoln as an ad." [21] Page [End Page 49]

Heath was baffled by Volk's insistence that the medallion would be corrupted if it carried the sponsor's name. No other artist, in his experience, had taken such a stand, objecting in principle to any association of the sainted Lincoln with a mere commercial enterprise. Numerous Whitehead & Hoag medals had been "executed by sculptors of renown, such as Bela Pratt," who had created the medalet for the A. Lincoln watch, and none expressed the least scruple about commercializing Lincoln. Heath thought that Bunn deserved "some slight consideration" in view of his choice of Volk's Lincoln over Lincoln portraits by other artists, the watch company's substantial investment in the project, and the "patriotic and educational" value of the essay contest. Heath also invoked the example of Tiffany's which, in a similar contest sponsored by the New York Times, had readily let the newspaper affix its name to thousands of medals. The watch company had already tentatively ordered eight thousand medals, and expected to increase the quantity to twelve or thirteen thousand "when they have heard from all the High Schools of the country." [22] This was no trifling transaction.

Hinton was also worried lest the project miscarry. He realized that he could not properly keep his name on the medal if Volk's was not there also, and it hurt him "not to have our names associated together on the medal. " He hesitated to endorse Volk's alternatives. In place of the watch company's name, Volk had suggested that the medal be inscribed "From friends in the home town of Lincoln," but this was hardly an adequate identification of the sponsor. Similarly, Volk had proposed in place of his own name the phrase, "From the Volk Life Mask," but this reference to the artist's use of his father's cast of Lincoln's face was also vague.[23]

Perplexed by the situation, Hinton turned to Will H. Low, his teacher and close friend whom he settled near in Bronxville, New York. Low lightheartedly observed that the medal would be two-sided: It would not "discredit" Volk to have his image of Lincoln on one side and the watch company's name on the other. More tellingly, as Hinton reported, Jacob Bunn himself, when he saw the initial design of the medal, "telegraphed right off" to "make the words of the watch co. even smaller" than sketched, to make them "as small as possible." [24]

Volk remained adamant. "After years of work devoted to the development of my picture of Lincoln I could never justify its use for Page [End Page 50] advertising purposes, no matter how delicately veiled they might be."[25] And so the matter came down to Volk's ultimatum: Either his name or the watch company's had to come off the medal.

There was no way for Whitehead & Hoag to resolve the issue until Jacob Bunn could be consulted, and he had left in July for an extended tour of Europe. Moving from place to place, he could not be cabled, nor did Heath think that all the nuances of the situation could be reduced to writing. For nearly two months, Whitehead & Hoag waited for Bunn's return and the opportunity to discuss the medal with him directly. [26]

Then, suddenly, Volk learned that Bunn was back in the country and had "agreed to leave the name of his Company off from [sic] the medal. " Volk was of course pleased by the news. He thanked Whitehead & Hoag for its "tempered patience in the situation. " He also admitted that, from Bunn's point of view, the change "entails something of a sacrifice," adding, however, that "Lincoln's life itself stood for sacrifice." [27]

Heath, Whitehead & Hoag's president, soon visited Bunn in Springfield, probably to hasten arrangements for the production of the medal. Writing to Volk, he described the place of Jacob Bunn Sr. in the Lincoln story, adding that Jacob Bunn Jr. thus came "naturally by his interest in and affection for Mr. Lincoln." Bunn showed Heath Lincoln's home, causing Heath to ask Volk for signed copies of Volk's portrait of Lincoln both for Bunn and the home. Altogether, as Heath wrote, Bunn was "a man of very fine sentiments."[28]

Those who knew Bunn closely felt the same, including, for example, Robert C. Lanphier, who developed the "meter department" Page [End Page 51] of the watch company into Sangamo Electric, a business that survived long after the demise of the parent company. Lanphier remembered Bunn, who was president of both companies, as "patient and understanding," a model of "tact and fairness." [29]

In 1923, as plans for the Lincoln essay contest took shape, Bunn demonstrated his integrity in another way. With his sister and two brothers, he initiated a search for the beneficiaries of the depositors in their father's bank. When the J. Bunn Bank failed in 1878, a casualty of the depression of the previous five years, it was able to pay some fourteen hundred depositors only 71.5 cents on the dollar. Although legally discharged from any further obligation, the elder Bunn felt a moral obligation to repay the depositors in full, with interest at 5 percent per annum. By 1925, the success of the watch company and other family businesses enabled his surviving children to distribute to the depositors or their heirs the full amount of the unpaid balance plus interest (240 percent). Altogether, nearly five thousand beneficiaries received $800,000. It was a singular gesture that gave the family an almost Lincolnesque reputation for honesty. The Bunns were such a prominent and respected family in Springfield that the press across the country reported the story as an act of noblesse oblige.[30]

Whether or not Douglas Volk ever knew of the largess of the Bunn family, he must have been pleased with the booklet that accompanied the Illinois Watch Company's Lincoln medal. Embossed on the front and back covers were the two sides of the medal. For the frontispiece, the watch company reproduced Volk's full painting, Page [End Page 52] "considered by the critics as the finest portrait of Lincoln ever painted." The booklet included brief biographies of Volk and Hinton and a description of the medal's production. The medal, "made of the finest solid government bronze," was about three inches in diameter (sufficient to qualify as a medallion), and it weighed nearly six ounces.[31] The raised image of Lincoln stood out on the front, and, in lower relief on the back, a wreath of oak leaves encircled the inscription. Together, they made the piece approximately three-eighths of an inch thick. The manufacturer's name—Whitehead-Hoag—appeared on the rim of the medal but not in the booklet.[32]

The collaboration of painter, sculptor, and die-maker yielded a medallion at once attractive and distinctive. The lettering of Lincoln's name on the obverse and the descriptive wording on the reverse were simple and harmonious, although local jewelers often inscribed the winner's name and date of the contest in an incongruous font. At Volk's suggestion, or at least with his concurrence, Hinton accentuated Lincoln's head, especially his shock of hair. Hinton also modeled the face with sensitivity, becoming unsure of himself only in rendering the president's eyebrows. He silhouetted the sharply defined head against both a flat background and the soft, low relief of the shoulders. Unlike most sculptors who contributed to medallic art in America, Hinton based his Lincoln on a painting of the subject. The piece was altogether a worthy addition to the art of the medal in the Beaux Arts tradition.

Whitehead & Hoag were proud of the watch company medallion. It was singled out for a step-by-step display of medallic production in a "process exhibit" at the Newark Museum in 1928 (Figure 6). Newark was at that time not only the home of Whitehead & Hoag but also the showcase of John Cotton Dana's expansive redefinition of the public library. As director of the Newark Museum as well as the Newark Library, Dana manifested a lively interest in machine art. "I would much prefer to show a Whitehead & Hoag Exhibit than I would an oil painting," he wrote to Chester R. Hoag, whose company had for years loaned or donated its products to Dana's museum. The exhibit of 1928 included different patinations of the watch company's medal, partly because Whitehead Page [End Page 53] & Hoag had borrowed back the dies to make additional medals for the Lincoln essay contest.[33]

The booklet announcing the contest was sent to twenty-three thousand American high schools. The watch company gave participating schools wide latitude in setting up the contest, yet it also offered the assistance of both its Lincoln Essay Bureau and the Lincoln Centennial Association (of which Paul M. Angle was the executive secretary and Jacob Bunn was a director). Principals and teachers could expect to receive "information and stories of the life of Lincoln" from time to time, and they could send in the name of each winner and a copy of each winning essay, if they wished. But nothing was required, and the efforts of the essay bureau were probably focused on mailings of the medal. The details of the contest were incidental to the company's hope that it would "increase the study of Lincoln," advance "the high ideals that Lincoln's life exemplified," and serve "as an incentive to better government."[34]

Although the medals first struck for the contest were dated on the anniversary of Lincoln's birthday in 1924, the booklet concluded with a letter of March 4, written by Francis G. Blair, the Illinois Superintendent of Public Instruction, which referred to "unavoidable Page [End Page 54] delays" in starting the contest—delays occasioned at least partly by Volk's stand against commercializing Lincoln.[35] When Volk opened the shipping carton containing the finished product, however, he must have been surprised to see that the medallion itself rested in a velvet-lined display case, on the lid of which was printed, in capital letters, the words Presented by / Illinois Watch Co. / Springfield (Figure 7). It seems never to have occurred to Volk, when he campaigned against the company's name on the medal, that it would appear on the case instead. Of course, case and medal often became separated in 1924 and afterwards. The number of medals now extant far exceeds the number of boxes and booklets. Nevertheless, Volk's victory was a limited one. In the end, he appeared rather like an artistic Canute, attempting to turn back the tide of commercialization that has ever engulfed Lincoln.

The Illinois Watch Company's essay bureau was apparently the responsibility of its advertising manager, William J. Barnes.[36] It was probably Barnes who ordered additional medals from Whitehead & Hoag from time to time. The patina of different medals varies substantially, and in one case, at least, even the year (1925) was stamped on the upper edge of the back of the medal.[37] Since the 1920s, thousands of the watch company's medals have become keepsakes, but the piece itself and the story behind it, except as reconstituted here, are unknown.

Bunn died in 1926, and in 1927 the family sold the company, although the Hamilton Watch Company used the plant to make Page [End Page 55]

Meanwhile, Charles Burnett, a career army officer with ties to Springfield, carried the idea of a Lincoln essay contest to Japan. Raised in Carlinville, where he attended Blackburn College, Burnett graduated from West Point in 1901. In 1925, en route to his third tour of duty as military attaché of the U.S. embassy in Tokyo, Lt. Col. Burnett visited his brother in Springfield and became aware of the watch company's essay contest. Back in Japan, he arranged for the America-Japan Society (Nichi-Bei Kyokai),[39] of which he was the secretary, to organize a similar competition, inasmuch as Lincoln belonged "to the world and not to the United States alone" ( Figure 8). [40]

Thus began a forgotten chapter in the story of Japan's veneration of Lincoln. After the Japanese earthquake of 1923, the America-Japan Society (safely based in Frank Lloyd Wright's Imperial Hotel, which did not collapse) fostered American relief efforts in Tokyo and otherwise endeavored to cultivate good relations between the two nations. The society promptly endorsed Burnett's proposal that it invite Japanese students to write essays in English about Lincoln. Writing to Springfield, Burnett enclosed a copy of the society's circular about the contest, portions of which he translated into English (Figure 9). [41]

The Lincoln Centennial Association accepted the responsibility Page [End Page 57] for judging the Japanese papers on Lincoln on the understanding that "only the obviously superior essays would be forwarded for its decision." Accordingly, Burnett sent fifty-nine essays to Paul M. Angle, who, with three leaders of the association—Henry A. Converse, Logan Hay, and George W. Bunn Jr.—painstakingly chose three winners in each class of participants, including at first not only college and university students (above the age of sixteen) but also middle-school pupils (between eleven and sixteen). The judges were "amazed at the grasp of the factual aspect of the subject exhibited in these essays" and were also impressed by the quality of the writing. To illustrate the point, Angle quoted a paragraph about Lincoln's Cooper Institute address in the prize-winning essay of a first-year student of Peers' College, Tokyo, and asked, rhetorically, "How many American College freshmen could surpass this passage, were they compelled to write in Japanese on the Emperor Meiji?" [42] Page [End Page 58]

The following February and on subsequent occasions close to Lincoln's birthday, the America-Japan Society met to present the prizes and listen to speeches. After each program, the society published the major addresses and selected essays. Prince Iyesato Tokugawa, president of the society, celebrated Lincoln as "a gallant and democratic American Samurai," and declared that the "spontaneous and unaffected reactions of the young men and women of Japan to his great personality" was proof that "there is no barrier nor difference between the souls of the East and of the West." The American ambassador to Japan reiterated Lincoln's transcendent role in cementing friendly relations between the two nations.[43]

"The reading of these papers," Angle observed, "offered some very interesting glimpses of the psychology of young Japanese." For example, the essays of many older students manifest a "keenness of feeling ... at our policy of Asiatic exclusion.... Repeatedly the statement was made that if Lincoln were alive today he would never have permitted the adoption of such a policy. " When Angle published one of the winning essays, even though it made no reference to immigration restriction, a reader sought to have it reprinted in the Seattle Times, so as to diminish the widespread "feeling of distrust" of the Japanese community on the West Coast.[44]

From the Lincoln Centennial Association (renamed the Abraham Lincoln Association in 1929), the prize winners received individually inscribed medals. In addition, the America-Japan Society awarded cash prizes: one hundred yen to first-place winners, fifty yen to the runners-up. Such prizes, Prince Tokugawa opined, are "humble ones," but the study of Lincoln's life was more valuable than "any material reward," for it enriched the winners "mentally and spiritually." [45]

The Illinois Watch Company's Lincoln medal was used as the frontispiece of each set of addresses and essays published by the Page [End Page 60] America-Japan Society. Burnett at one point alluded to the essay program in the United States, established by "Mr. Jacob Bunn, whose father had been a life-long friend of Lincoln,"[46] but nowhere in the society's annual publications was the watch company itself mentioned. The omission would have pleased Douglas Volk.

Nevertheless, so long as the America-Japan Society awarded watch-company medals to the best essayists, it depended upon corporate support. In the spring of 1928, before announcing the third competition, Burnett inquired about "the feasibility of continuing the essay contests even though the Illinois Watch Company is no more. " To clarify the situation, he turned to his brother, Samuel T. Burnett, clerk of the U.S. District Court in Springfield, who then explained to a Hamilton Watch Company executive how the Illinois Watch Company supplied the medals. "That of course has been pure philanthropy, since the Company's name has not appeared in any manner" (at least not on the medal itself). Admitting that Hamilton's attention to business may "leave little room for ventures such as this," Burnett pointed out "the difficulty of continuing the contest without medals of some kind." Although Angle suggested that a biography of Lincoln might be awarded in lieu of the watch-company medal, the America-Japan Society, in cooperation with the Lincoln Centennial Association alone, decided in effect to carry on as long as the supply of medals lasted. On this basis, Angle handled the judging of Japanese student essays for two more years.[47]

In 1930, however, the America-Japan Society postponed its Lincoln program until March due to a "delay in the arrival" of the prizes. Of the thousands of medals made by Whitehead & Hoag for the Illinois Watch Company, Angle had obtained the last few that the manufacturer had on hand, and the Abraham Lincoln Association lacked the means to order more. Furthermore, Angle, an Page [End Page 61] accomplished writer himself, had become critical of the essays. The best of the lot was chosen because of its content but the "language of the paper" was "not particularly good."[48] Angle had no doubt become bored with the task of reading awkward prose. Yet, if the contest had not expired for internal reasons, it would surely have collapsed after 1930, as the rise the Japanese militarism strained relations between the United States and Japan.

After only four or five years, interest in the Lincoln essay contest both in the United States and in Japan waned. Those who succeeded Bunn and Burnett lacked their commitment to the purposes of each program, and corporate support came to an end. Angle was realistic about the commercialization of Lincoln. When a director of the Abraham Lincoln Association complained about an advertisement for the Lincoln National Life Insurance Company of Fort Wayne, Indiana, Angle replied: "It is entirely impossible, I suppose, to prevent 'commercialized' use of the name of Lincoln." Angle could not see that the insurance company's use of the name, however regrettable, was "any different from the use to which it was put" in the Illinois Watch Company's essay contest. In fact, in 1905 Robert Todd Lincoln himself had given the insurance company permission to use Lincoln's name and image. [49] Jacob Bunn's aim in creating the watch company's essay contest was no less acceptable. Indeed, it was commendable in its restraint, compared with the crass appropriation of Lincoln that was so widespread by the 1920s. In retrospect, it was not merely the Japanese continuation of Bunn's program that made it distinctive but, more especially, the short, obstinate, and essentially futile effort of Douglas Volk to stem the commercial exploitation of Lincoln. Page [End Page 62]

Notes

-

The phrase is Douglas Volk's, in Volk to

Walter C. Heath, July 21, 1923, one of a series of twenty-nine

letters on the subject in the Volk family papers. The collection is

now owned by Mrs. Jessie Volk of Center Lovell, Maine, and includes

the letters of 1923 and the undated sketches that are cited in

these notes.

The author wishes to thank Mrs. Volk

for making this collection available for research and for her

hospitality at Hewnoaks, her summer home. The author is also

indebted to James Cornelius of the University of Illinois,

Urbana-Champaign, for critiquing drafts of this article. This study

was supported in part by a grant from the University's Research

Board. More generally, the author wishes to acknowledge the

assistance of Mark L. Johnson of the Historic Sites Division of the

Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, who has freely shared his

discoveries of "Volk stuff" of every description.

-

Conversely, Lincoln was Bunn's lawyer.

-

The company's name was embossed on the back

cover of a book of albertypes issued by Adolph Wittemann, the

ubiquitous publisher of that genre. The company also distributed

complimentary copies of Souvenir of Springfield (circa

1890), another accordion-style viewbook with larger pictures

published by H. E. Barker and copyrighted by J. C. Power.

-

William "Bill" Meggers and Roy Ehrhardt,

American Pocket Watch Encyclopedia and Price Guide, vol. 2,

Illinois Watch Co. (Kansas City, Mo.: Heart of America Press,

1985), 45, 154, and advertisements, passim. The "Mary Todd"

was briefly included in the company's line of ladies wrist watches,

circa 1928. Ibid., 226. (If correctly dated, the Mary Todd was

marketed just after Hamilton bought out the Bunns.) The Book of

A. Lincoln Watches, a handsome booklet published in 1924 by the

Illinois Watch Company and Lebolt & Company, New York, combined

a sketch of "Lincoln in Springfield" with a description of several

models of the watch. For information regarding the A. Lincoln

watch, the author is indebted to Russell W. Snyder, Urbana, Ill.

-

Robert T. Lincoln to C[leveland] C. Bierman

(lawyer and secretary, Lincoln College of Law, Springfield, Ill.),

August 13, 1910, Robert Todd Lincoln letterbooks, Illinois State

Historical Library, Springfield (microfilm, roll 77, p. 265), and

see Mildred V. Schulz, "For the Record," Dispatch from the

Illinois State Historical Society 4 (June 1972), [7].

-

The medalet is no. 564 in Robert P. King,

"Lincoln in Numismatics," The Numismatist 37 (February

1924), 139. It is pictured, for example, in Stuart Schneider,

Collecting Lincoln (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1997),

146. Pratt's signature is barely visible on the truncation of the

bust of Lincoln. He "pacified" the design on the back by placing an

olive branch in the eagle's talons and removing the battle-ax from

the fasces. Atop the piece is a loop to fasten it to a watch chain

or badge.

The watch company's medalet was

adapted from a medal for the New York Lincoln Centenary Committee's

commemoration of Lincoln's birth simply by expunging the year

"MCMIX" and substituting "1809–1865. " See Cynthia (Pratt)

Kennedy Sam, "Bela Lyon Pratt (1867–1917): Medals, Medallions

and Coins," The Medal in America, ed., Alan M. Stahl (New

York: American Numismatic Society, 1988), 176, and, for four

renderings of the New York medal, King, "Lincoln in Numismatics,"

nos. 313, 322, 335, and 389.

The manufacturer further extended

the life of Pratt's profile of Lincoln by changing the wording on

the back to serve other purposes—for example, to advertise

newspapers, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the

Gettysburg Address, and to recognize the trek of Boy Scouts from

New Salem to Springfield, Illinois. (For more than three decades,

beginning in 1926, the Abraham Lincoln Council of the Boy Scouts of

America awarded the Pratt medalet to scouts who took the "Lincoln

Trail," inscribing in capital letters that the hiker had "walked in

Lincoln's steps" on a specified date. That experience no doubt

continues to leave hundreds of scouts with the impression that

Lincoln, as Donald Hoffmann once put it, was "the world's first

commuter.")

-

Again, hundreds of the prints survive and have

become a staple of online auctions, where they are inaccurately or

incompletely described. Even when the picture is recognized as a

print, not a painting, the piece is sold without identifying Rudolf

Bohunek as the artist whose portrait of Lincoln was the basis of

the print. "R. Bohunek" was indistinctly stamped on the back of the

canvas, and part of his last name was folded under the frame.

Bohunek arrived in Chicago in 1913,

the date on the Lincoln print. In subsequent years, he moved to Oak

Park and established a studio in the Loop, first at 536 S. Clark

St. and then at 616 S. Michigan Ave. Born in Bohemia about 1875,

and trained in Prague, he lived in New Orleans from about 1909 to

1911, painting copies of early portraits of such French founders as

La Salle and Iberville. After briefly returning to Prague, he

settled in Chicago. See Lakeside Annual Directory of the City of

Chicago, 1913, and the annual Directory for 1914, 1915,

1916, and 1917; John A. Mahé II and Rosanne McCaffrey, eds.,

Encyclopaedia of New Orleans Artists, 1718–1918 (New

Orleans: Historic New Orleans Collection, 1987), 45; Robert Glenk,

Handbook and Guide to the Louisiana State Museum (New

Orleans: Louisiana State Museum, 1934), 48, 51.

Bohunek derived his Lincoln portrait

from one of Anthony Berger's photographs of February 9, 1864, taken

at Mathew Brady's studio in Washington, D.C. See Charles Hamilton

and Lloyd Ostendorf, Lincoln in Photographs: An Album of Every

Known Pose, revised ed. (Dayton, Ohio: Morningside House,

1985), 178, 395.

-

Bunn, quoted in Heath to Volk, June 1, 1923.

-

Whitehead & Hoag, incorporated in 1892 by

Benjamin S. Whitehead and Chester R. Hoag, were pioneers in the

design and manufacture of advertising art. A collection of their

products, which were "astronomical in their variety," is in the

Newark Museum. Unfortunately, when Whitehead & Hoag was bought

in 1959, the records of its main office and plant were destroyed,

although the Hoag family has collected other company materials,

including records of its satellite offices. Verdenal H. Johnson

(Hoag's granddaughter) to the author, October 13, 2001.

Whitehead & Hoag's Lincoln items

are numbered and described in several lists, beginning with Robert

P. King, "Lincoln in Numismatics," The Numismatist 37

(February 1924). King published two supplements, and Paul H.

Ginther and Nathan N. Eglit compiled a third. Ibid., 40 (April

1927), 46 (August 1933), and 72 (December 1959). In 1966 the Token

and Medal Society reprinted King's work as Lincoln in

Numismatics, and a year later the society issued Edgar Heyl,

A Comprehensive Index to King's Lincoln in Numismatics. See

also Robert L. Kincaid, "Lincoln in Numismatics: The Story of

Robert P. King, Authority on Lincoln Coins and Medals," Lincoln

Herald 46 (October 1944), 34–38. For information on

Lincoln medals and answers to other numismatic questions, the

author is indebted to Francis D. Campbell and Michael L. Bates of

the American Numismatic Society, New York City.

-

Heath to Volk, June 1, 1923.

-

Lincoln to C. Powell Minnigerode (Director,

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), January 23, 1922, copy

in Volk Family Papers; Tarbell, quoted in Buffalo Fine Arts

Academy, Albright [Albright-Knox] Art Gallery, Buffalo, N.Y.,

Academy Notes, July–December 1922, 49.

-

See Heath to Volk, June 1, 1923.

-

Volk to Heath, June 7, 1923. Demonstrating

his versatility in painting, Hinton executed oils, water colors,

and murals as well as copies of the masters. Volk offered one such

copy to Florence (Mrs. William) Sloane for the Hermitage, her home

in Norfolk, Va. In effect, he thus shared the commissions which she

gave Volk himself. See Volk to Mrs. Sloane, April 12, 1918,

Archives, Hermitage Foundation Museum.

-

Charles C. Curran (Secretary, National

Academy of Design) to Volk, January 22, 1935, and see Hinton to

Volk, January 26, 1933, Archives, National Academy of Design, New

York City. The author is indebted to David B. Dearinger, the

academy's chief curator, for making available its files on Volk and

Hinton. Regarding Hinton, see also New York Herald Tribune,

October 14, 1950, p. 12, col. 5.

-

National Sculpture Society, Exhibition of

American Sculpture Catalogue ... (New York: National Sculpture

Society, 1923); George F. Hill on portrait medallions, Preface to

Theodore Spicer-Simson and Stuart P. Sherman, Men of Letters of

the British Isles ... (New York: William Edwin Rudge, 1924),

12; and see Barbara A. Baxter, The Beaux-Arts Medal in

America ... (New York: American Numismatic Society, 1987).

-

Heath to Volk, July 2, 1923; Hinton to Volk,

June 29, July 7, July 9, 1923.

-

Volk to Heath, July 27, 1923; Hinton

sketches, n.d.

-

Joan Parks, "Our Famous Neighbors," Daily

Times (Mamaroneck, N.Y.), May 4, 1932 (clipping in Hinton file,

National Academy of Design); Hinton to Marion Volk, August 3, to

Douglas Volk, August 6, 1923.

-

Volk to Heath, June 7, July 21, 27, August

6, 1923; Heath to Volk, July 25, 1923.

-

Rather distinctively, Hinton placed the

shaft of a burning torch through the center of the numbers, which

gave the years of Lincoln's birth and death.

-

Volk to Heath, July 21, August 15, 1923;

Hinton to Volk, August 4, 1923; and see Volk to Heath, July 27,

1923.

-

Heath to Volk and see Hinton to Volk, both

August 6, 1923.

-

Volk to Hinton, July 21, August 13, 1923;

Hinton to Volk, August 6, 1923.

-

Hinton to Volk, August 6, 15, 1923, and see

Heath to Volk, July 25, 1923.

-

Volk to Hinton, August 15, 1923.

-

See Heath to Volk, July 25, August 6, 28,

1923.

-

William A. Jones (Vice President, Whitehead

& Hoag) to Volk, September 18, 1923; Volk to Jones, September

21, 1923, and see Heath to Volk, September 24, 1923.

Benjamin S. Whitehead, although not

directly engaged in breaking the impasse between Volk and Bunn, was

a friend and summer neighbor of Volk's in Maine. He evidently so

admired the painting of Lincoln which was used for the medal that

he acquired another portrait in the series, "Lincoln, the

Ever-Sympathetic" (1931). In 1966 Whitehead's granddaughters gave

the portrait to the White House. It was promptly hung in the

Lincoln Room, replacing Volk's first Lincoln portrait, which had

been on loan from the National Gallery of Art. See "A New View of

Lincoln in the White House," Washington Post, July 3, 1966,

Sec. F, p. 2.

-

Heath to Volk, July 25, October 12, 1923. It

seems possible that the reproduction of Volk's painting that Bunn

received is the three-quarter-length portrait, on the frame of

which are the labels Illinois Watch Company and

Springfield. The Sangamon Valley Collection of the Lincoln

Library (Springfield's public library) contains a photograph of

this reproduction as so framed (see Figure 3).

-

Robert C. Lanphier and Benjamin P. Thomas,

Sangamo: A History of Fifty Years (Chicago: privately

printed, 1949), 27, 66.

-

F. A. Behymer, "For the Honor of the

Family," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 3, 1926, Part 7,

p. 1 (entire page). This article was abridged in Literary

Digest 88 (January 30, 1926), 48, 52, 54. Of the dozen

paragraphs excised in whole or part, one noted the effort of Jacob

Bunn Sr. to build up the Illinois Watch Company so as to pay the

bank's indebtedness: "At the watch factory he worked night and day.

He kept it from failure, but it was a business that would only be

made to grow slowly ... " On December 27, 1925, numerous papers,

including the Post-Dispatch (p. 1, col. 1) and the New York

Times (Sec. 1, p. 2, col. 4), carried the announcement of the

Bunn family disbursements. It was the lead story in Springfield's

Illinois State Journal and Illinois State Register.

See also "Bunn Memorial Trust," Journal of the Illinois State

Historical Society 18 (January 1926), 1063–65. Mindful of

the Bunn family's Lincoln interests, several beneficiaries turned

over their checks to the Lincoln Centennial Association. George W.

Marney, "'A Good Name is Rather to be Chosen than Great Riches':

Jacob Bunn's Pledge Redeemed by His Heirs," Illinois Journal of

Commerce 8 (February 1926), 28.

-

More exactly, the medal in the American

Numismatic Society (1924.150.11), according to the Society's

database, is 75 millimeters in diameter and weighs 168.791 grams.

-

Lincoln Essay Contest to Increase

Knowledge and Admiration of Lincoln Among School Children in the

United States (Springfield: Illinois Watch Company, [1924]),

12, 16.

-

Dana to Hoag, October 20, 1927, quoted in

Dorothy Budd Bartle, "John Cotton Dana and the Ideal Museum

Collection of Medals," in Stahl, Medal in America, 115, and

see 102–17, passim.

Interestingly, Douglas Volk

completed a portrait of Dana in 1923, although he gives no

indication in his correspondence with Whitehead & Hoag that he

knew of the company's support of Dana's museum. The portrait is

reproduced in The Museum (Newark Museum Association), 15

(1963), 47.

-

Lincoln Essay Contest, [6], 11, 21.

-

Blair's letter to High School Principals as

printed in Lincoln Essay Contest, 23–24, differs from

the text in the Thirty–fifth Biennial Report of the

Superintendent of Public Instruction of [the] State of Illinois,

July 1, 1922–June 30, 1924 (Springfield: Schnepp &

Barnes, 1924), 25–26. It seems possible that the circular was

edited at the watch company to shorten it and to delete Bunn's

name.

In King's first supplement (cited in

note 9), the medal is no. 891. However, Blair's letter and related

evidence cast doubt on King's statement that Bunn presented the

first medal to be struck to David Lloyd George, who, on October 18,

1923, came to Springfield for an address on Lincoln. The former

prime minister's moving tribute was printed in the Lincoln

Centennial Association's first Bulletin (December 20,

1923).

-

See Barnes to Angle, May 11, 1927, January

13, May 28, 1928, Abraham Lincoln Association Papers, Illinois

State Historical Library. This collection contains all the

correspondence that is subsequently cited in these notes.

-

In recent years, Bill Jacques, owner of the

StonePost Corporation of East Dummerston, Vermont, has marketed a

uniface reproduction of the medal, giving the image of Lincoln a

bronze finish, mounting the piece on a square plaque of cherry

wood, and advertising it as dating from 1909 (a common error among

collectors).

-

Angle to Helen Roberts (English instructor,

Star, Idaho), January 17, 1930.

-

In the Japanese translation, the association

is the Japan-American Society.

-

America-Japan Society, The Third Lincoln

Essay Contest Conducted by the America-Japan Society in

Co-operation with the Lincoln Centennial Association, Springfield,

Illinois, Special Bulletin 8 (Tokyo: America-Japan Society,

1929), 5, and see ibid., The Second Lincoln Essay Contest

... , Special Bulletin 6 (1928), 5–6, and ibid., The

Fourth Lincoln Essay Contest ... , Special Bulletin 10 (1930),

5. Regarding Burnett, see The National Cyclopaedia of American

Biography, 76 vols. (New York: James T. White & Co.,

1891–1984), 29 (1941): 404–5.

-

C. Burnett to Secretary, Lincoln Centennial

Association, October 12, 1926, and enclosures. The author thanks

Yuriko Oono of the University of Illinois Library for translating

the America-Japan Society circular in its entirety.

-

Angle to Burnett, December 2, 1926; Lincoln

Centennial Association, Bulletin, no. 7 (June 1, 1927), 3,

7; America-Japan Society, The Lincoln Essay Contest Conducted by

the America-Japan Society in Co-operation with the Lincoln

Centennial Association, Springfield, Illinois, Special Bulletin

4 (Tokyo: America-Japan Society, 1927), 12.

-

Lincoln Essay Contest, 2; Second

Lincoln Essay Contest, 2; and see remarks of Ambassadors

Charles MacVeagh and William R. Castle in the America-Japan

Society's Lincoln essay contest publications. That the contest

would inspire Japanese students to emulate Lincoln was also assumed

by Emanuel Hertz, in Lincoln of Illinois: The Testimony of the

Nations (n.p., n.d., 1930), 20–21.

-

Lincoln Centennial Association,

Bulletin, no. 7, 7; Jonathan Smith to Angle, June 14, and

see Angle to Smith, June 22, 1929; Sumiko Tokuda, "Abraham Lincoln:

A Japanese Interpretation," Abraham Lincoln Association,

Bulletin, no. 15 (June 1, 1929), 1–4, 7–8.

-

Third Lincoln Essay Contest, 4.

-

Second Lincoln Essay Contest, 5.

-

Charles Burnett to Angle, March 13; S. T.

Burnett to Robert E. Miller (Vice President, Hamilton Watch Co.),

May 24; and see Angle to Miller, May 24, 1928. The number of

submissions fluctuated (down to 19, then up to 55), even though

middle-school students were excluded from the contest after the

first year. Charles Burnett to Angle, October 24, 1927, Eugene H.

Dooman (Secretary, America-Japan Society), September 30, 1929.

Additional letters in the Abraham Lincoln Association Papers

indicate how Samuel T. Burnett facilitated mailings between Tokyo

and Springfield. For biographical data on Burnett, see George W.

Smith et al., History of Illinois and Her People, 6 vols.

(Chicago: American Historical Society, 1927), 4:38–39, and

Illinois State Journal, February 10, 1944, p. 10, cols.

4–5.

-

Fourth Lincoln Essay Contest, 3, 10,

and see Angle to Dooman, October 28, November 14, 1929.

-

Paul M. Angle to Arthur D. Mackie

(Springfield), April 27; and see Mackie to Angle, April 26, 1929.

See also Frank F. Fowle (Chicago) to Angle, April 20, Angle to

Fowle, April 22, 1929, and Merrill D. Peterson, Lincoln in

American Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 197.

Peterson overlooks the watch company's contest in the United States

but briefly alludes to the competition in Japan. However, he cites

only reports in the New York Times of gatherings of the

American Association of Tokyo and Yokohama, not of the

America-Japan Society. Ibid., 206; 415, n. 18.

Although Angle at one point thought

that the Lincoln National Life Insurance Company had "acquired the

rights to use" the watch company medal in a continuation of the

Lincoln essay contest, there is no record that it took any steps

toward that end. Angle to F. M. Thompson (Vice Principal,

Riverdale, Calif.), August 7, 1929; Cindy VanHorn (Lincoln Museum)

to the author, October 5, 2001.