Lincoln at the Millennium

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

On April 19, 1865, within a week of Abraham Lincoln's assassination, Horace Greeley surmised "that Mr. Lincoln's reputation will stand higher with posterity than with the mass of his contemporaries—that distance, whether in time or space, while dwarfing and obscuring so many, must place him in a fairer light—that future generations will deem him undervalued by those for and with whom he labored."[1] Greely's prediction is difficult to assess. "Future generations" means one thing; "posterity," another. What is Lincoln's status today?

Abraham Lincoln and America's Memory Crisis

Abraham Lincoln's place in American memory diminished noticeably during the last half of the twentieth century. The change was inevitable, for Lincoln is the hero of a nation no longer in close touch with its past. "Any revolution, any rapid alteration of the givens of the present," Richard Terdiman observes, "places a society's connection with its history under pressure," and as that pressure builds a "memory crisis" ensues. [2] To what kinds of revolu- Page [End Page 1] tion, however, is Terdiman referring? What "givens of the present" have suddenly shifted? How precisely does "history under pressure" differ from history free from pressure? How will we know a "memory crisis" when we see it? Does such a crisis induce us to ignore Lincoln, prevent us from identifying with him, or both?

Many will disagree with the claim that Lincoln's reputation has declined, and they can make a good case. They can cite the construction of new Lincoln libraries and museums and the expansion of old ones, the sheer number of Lincoln associations, the discovery of new information about Lincoln's youth, legal career, and presidency, the reanalysis of existing data and the doubling of Lincoln monographs published during the past twenty years. But does the quality and quantity of Lincoln scholarship and the vitality of Lincoln associations reflect Lincoln's place in the imagination of ordinary Americans?

The first nationwide survey of Lincoln's reputation, taken in July 1945 by the National Research Opinion Center (NORC), showed 57 percent of respondents naming Lincoln "one of the two or three greatest Americans." [3] NORC never repeated its question, but in 1956, halfway through Dwight Eisenhower's presidency, the Gallup Poll conducted the first of a series of surveys on presidential distinction. Each survey asked respondents to name the three greatest American presidents. In 1956, 62 percent of the respondents named Lincoln. By the time of the next survey (1975) this figure had fallen to 49 percent. In the next survey (1985) it fell slightly to 47 percent; in the next pair of surveys, taken at the beginning and end of 1991, it dropped to 43 and 40 percent, respectively. In 1999, it remained at 40 percent. [4] During the last half of the twentieth century, Lincoln consistently ranked first or second in greatness, but the absolute percentage of people naming him one of the three greatest presidents fell by more than a third. This decline appears within every category of race, sex, age, political preference, income, education, region, and place of residence. [5] Page [End Page 2]

Since the Gallup Poll asks respondents to name no less than three presidents, prestige deterioration manifests itself in diffused preferences. In 1956, two of the three top-rated presidents—Roosevelt and Lincoln—were named by more than 60 percent of the respondents; one of the three, Washington, was named by almost 50 percent. By 1999, the highest rated presidents—Lincoln and Kennedy—were named by only 40 and 35 percent, respectively; Roosevelt placed third at 24 percent, tied with Washington, Reagan, and Clinton. Recent presidents receive the nominations that the most popular presidents have lost.

Citation counts do not measure Lincoln's prestige as directly as surveys do, but they locate the context of its decline more precisely. Entries from the New York Times Index, for example, are relevant to Lincoln's changing stature because they reflect the demands of a general reading audience. Times articles on Lincoln increased from the 1909 Centennial to the 1959 Sesquicentennial, then, after 1960, fell suddenly and far. The Times printed a yearly mean of 58 articles on Lincoln during the 1930s, 42 articles during the 1940s, 52, during the 1950s. The mean number of articles published yearly during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s dropped to 26, 10, and 7, respectively. From 1990 to 1999 the volume remained at 7. Readers' Guide and Congressional Record trends are almost identical. [6]

Visits to Lincoln monuments and shrines, another indicator of his prestige, either diminished or leveled off during and after the 1960s. Lincoln's Tomb in Springfield, Illinois, drew 508,000 visitors yearly during the 1950s, peaked at 676,000 per year during the 1960s, then dropped through the next two decades. Visitation to Lincoln's Springfield home dropped from more than 650,000 per year during the last half of the 1960s to 531,000 per year during Page [End Page 3] the early 1990s. (By the late 1980s, street signs directing visitors to the Lincoln shrines had been replaced by new signs directing them to the Lincoln sites.) The annual number of visitors to Lincoln's boyhood home in Gentryville, Indiana, dropped from 240,000 in 1977 to 228,000 in 1991. Visitation to reconstructed New Salem (Illinois), the village where Lincoln spent his young adulthood, also diminished substantially from more than one million per year during the late 1960s to about a half-million during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Lincoln's birthplace (Hodgenville, Kentucky) visitation rose steadily from 245,000 per year during the 1950s to more than 400,000 during the early 1970s, then fell to the present level of 309,000. The Lincoln Memorial attracted 1.8 million visitors per year during the 1950s, 3.5 million during the 1960s, and has since decreased slightly. (Visitation rates leveled off well before the erection of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Holocaust Museum, Korean War Veterans Memorial, and other competing sites.) Since different site managers use different methods of counting visitors, the trends are erratic; however, the overall pattern is clear: in no case have visits to a Lincoln shrine or monument increased between the 1960s and the 1990s.[7]

Before the Memory Crisis

Surveys, citation, and visitor counts are useful indicators of reputational change, but they do not take us far enough; they do not allow us to grasp one generation's ideas of Lincoln and compare them to the ideas of another. I have approached this problem not by trying to put myself into the minds of people in different generations and recording what I thought about Lincoln, but by analyzing the visual images with which people represented Lincoln to themselves and to one another." [8] Changing dramatically from the 1930s to the present, these images reflect fundamentally different ways of thinking about, feeling, and judging the past. Page [End Page 4]

Picturing Lincoln: 1932–1941

Visual images of Lincoln provide a basis of historical perception that takes us beyond what we can know through statistical methods alone. Visual art, like literature, "is social evidence and testimony. It is a continuous commentary on manners and morals. Its great monuments ... preserve for us the precious record of modes of response to peculiar social and cultural conditions."[9] Visual art distinguishes generations from one another by representing their worldviews and helping us to penetrate their moral and affective habits of the heart. The feelings a people have for the past appear in many places other than art, but nowhere more vividly. "What do we think of," asked Charles Horton Cooley, "when we think of a person?" "Probably, if we could get to the bottom of the matter, it would be found that our impression of a [person] is always accompanied by some ideas of his sensible appearance...." Sensible appearances are good not only for thinking about people but also for thinking about what they represent:

During the 1930s, Cooley's and Fenichel's statements rang true. The American Railroad Company, for example, advertised its Page [End Page 5] Washington routes by showing a child and his grandfather at the Lincoln Memorial, their hats removed, looking upon the marble statue. The elderly man[12] grasps his cane, symbolic lifeline to the Civil War, as he points to the statue and the revised inscription engraved on the wall behind it, explaining to his grandson who Lincoln was and what he did ( Figure 1). Similarly, the Bell Telephone Company depicted a youngster standing in front of Lincoln's portrait as he listens to his uncle, for whom "the memory of the Great Emancipator was a kind of religion" (and his likeness, accordingly, a sacred icon). No wonder the Chicago Tribune's depicting young men en masse moving confidently toward the future (Figure 2) made sense. If they see brightness over the horizon it is because they know Lincoln and follow his way. They do not see the venerable President Lincoln, or even the successful lawyer, but the young farm boy with ax and book. Here is a celebration of self-reliance that one expects to find in conservative newspapers like the Chicago Tribune, but it represents the values of all Americans, liberal and conservative alike.

The meaning of a picture to viewers or, for that matter, an artist, cannot be inferred directly from its content; but artists know what peculiarities move their viewers, for artists and viewers inhabit the same community. That is why Lincoln images of the 1930s seem so peculiar to so many today: They tap 1930s sentiments by conforming to 1930s artistic conventions. Pictures of people looking at pictures of Lincoln embody one of these conventions. Surely, these are not studies of what people look like when they are looking at something ("studies in looking," so to speak); they are studies of people in communion with their past, drawing upon the vital symbols of their nation's traditions, locating themselves in time, identifying themselves with something capable of giving meaning to their lives.

Representations of Lincoln looking down upon and touching the people, as in a Chicago Tribune depiction of his lending a hand of encouragement to a struggling young student (Figure 3), embodies another obsolete artistic convention, one that displays the subject in an "active voice," not merely an image to admire in the present but an inspiration for the present, not an object to study and contemplate but a life to copy. Page [End Page 8]

Picturing Lincoln: 1942–1945

Since crises induce people to scan the past for moral and psychological anchors, the Great Depression "came as a sort of salvation.... Rather like the insulin treatment of modern therapy, the shock of [economic] depression brought our artists back from the shadows of [1920s] apathy or hostility to a more fruitful share in our common heritage." Abraham Lincoln played a key symbolic role in this artistic renaissance, this "decade of convictions" and "romantic nationalism." [13]

Abraham Lincoln's life, tightly incorporated into a decade-long pattern of economic deprivation, assumed special meaning in the ensuing war. Two months after Pearl Harbor, Chicago servicemen attracted large and enthusiastic crowds after assembling around Lincoln's statue. In New York, veterans and Boy Scouts conducted their ceremony at Henry Kirk Brown's statue of Lincoln in Union Square. Fred Lee, a Chinese-American youngster, climbed to the top of the pedestal and placed on it a floral wreath forming V for victory. In Philadelphia, the Daughters of Union Veterans, joined by Boy Scouts, held their ceremonies with unprecedented solemnity at Randolph Rogers's giant Lincoln statue in Fairmount Park. The Women's Army Corps formally inducted young women at the Union League in front of J. Otto Schweizer's Lincoln's statue. In Washington, President Franklin Roosevelt, amid pomp and music, presented himself at the Lincoln Memorial. Bareheaded despite the February cold, he stood at attention as a military aide laid his floral wreath at the feet of the seated Lincoln. Everywhere, Lincoln's Birthday rituals centered on Lincoln's visual image.

Pictures of the people looking at Lincoln are reciprocals of pictures of Lincoln looking at the people. Each type of picture suggests that Lincoln's life is not just a story to recall but a model for living—a model honored more in the breach than in the observance, as all models are, but nonetheless salient as a source of direction and encouragement. On February 12, 1942, after two months of devastating military defeats, Lincoln's image appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer, consoling Americans, symbolized by Uncle Sam, for their losses and grief, encouraging them to endure despite all (Figure 4). To that same end, magazines and newspa- Page [End Page 10] pers featured Lincoln together with his letter to Mrs. Julia Bixby of Massachusetts, mother of five sons believed to have died in the Civil War. In one of these pictures ( Figure 5), offered gratefully by the Weatherhead Company of Cleveland, Ohio, to "those whose sons have died in battle," Lincoln refers to the dead of the new war, expressing "the thanks of the republic they died to save" and acknowledging to their parents "the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom." We cannot say how many parents saw this advertisement or accepted Weatherhead's offer, but those who did must have shared its premise: that certain incidents in the Civil War, however remote and however little they knew about them, somehow gave meaning to the worst experience of their lives.

In these wartime images, included by Robert Penn Warren among the prominent legacies of the Civil War, [14] Lincoln embodies the ultimate meaning of devotion, suffering, death, and grief. Defining present crises as episodes in the national story, Lincoln representations of the 1930s and 1940s made contact with the deepest feelings shared by the American people, brought those feelings into the open where they could be recognized, and, connecting them to the great dangers of the past, infused them with purpose. Representations of Lincoln worked so well because they were part of the political aesthetics of a society that retained the deferential sentiments of the late nineteenth century, when much of its population was born. That the pictures seem corny today is essential to understanding how different from ours was the mentality of the generation for which they were created. Richard Merleman's concept of the "tight-bounded moral community," consisting of political, religious, educational, and kinship structures linking the experience of their members to the moral values of the culture, [15] captures this mentality. Because tightly bounded communities are at once strong-minded and narrow-minded, resilient and provincial, however, the same late-Victorian virtues that made the generation of the 1930s and 1940s "the Greatest Generation," the generation wherein Lincoln's reputation peaked, also made it a generation of racism, anti-Semitism, and crude nativism. Page [End Page 11]

Picturing Lincoln: 1960–2000

In 1938, James Stewart portrayed a young senator so enthralled with Lincoln that he visited his Memorial whenever he needed moral uplift. Frank Capra's Mr. Smith Goes to Washington may be unappreciated today, but the film made sense to its audience for the same reason the era's cartoons and illustrations made sense: it drew on Lincoln's legacy as a guiding pattern of self-defining ideals.[16]

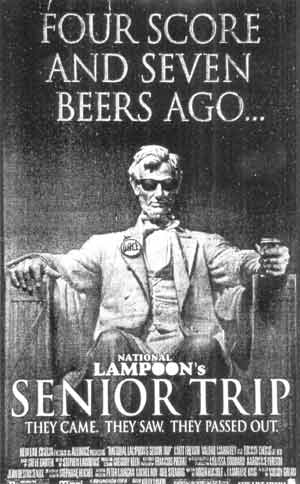

Art styles, however, are inseparable from the mentalities they evoke, and the styles disappear as the mentalities change. By the 1960s, Americans were representing Lincoln in strikingly new ways. Here Lincoln wears a party hat and blows a whistle to mark a bank's anniversary; there he plays a saxophone to announce a rock concert. Elsewhere, on a 1994 cover of Scientific American (Figure 6) he walks arm in arm with Marilyn Monroe. The designer, modifying old photographs to advertise the power of digital forgery, makes Lincoln appear prudish and stuffy beside the vivacious Marilyn. In the logo for the film Senior Trip, Lincoln appears on his Memorial chair of state grasping a can of beer (Figure 7), wearing sunglasses and an anti-Dole button. Behind his statue, the actual inscription to the Savior of the Union is changed to a parody of the opening lines of the Gettysburg Address: "Four Score and Seven Beers Ago...." The story line, dimwitted high school students visiting Washington, D.C., is sustained by our era's comedic conventions: vomiting, flatulence, urinating, drunkenness, teachers and students copulating with one another.

To use Abraham Lincoln to advertise low kitsch is to materialize a new way of experiencing the world. Jon Stewart, a late-night television comedian, talk-show host, sometime actor, and "Sultan of Savvy" exploits the new worldview by choosing Lincoln to advertise his Naked Pictures of Famous People ( Figure 8). None of Stewart's eighteen satirical chapters, including "Princess Diane writes Mother Teresa" and "Martha Stewart's Vagina," has anything to do with Lincoln, but he is pictured naked on the cover wearing his high hat, his two hands covering his genitals. Stewart needs a ridiculously modest Lincoln to affirm, through contrast, the new sexual revolution.

The new status of homosexuals in society is part of the new sexual revolution. Gay activist Larry Kramer, lecturing on "Our Gay Page [End Page 14]

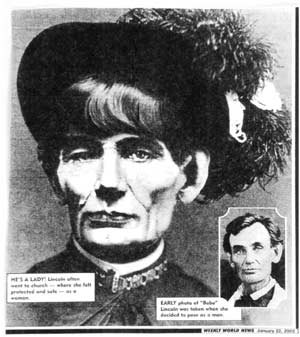

President" to a University of Wisconsin conference, claimed to have new documentary evidence that Lincoln and his friend Joshua Speed were homosexual partners. Kramer's statement, first published in the online magazine Salon, caused great stir. [17] In an obliquely related article, the Weekly World News, sold at the nation's supermarket checkout counters, published a front-page expose announcing that Abraham Lincoln was in truth a woman named Page [End Page 15] Abigail Lincoln ( Figure 9 ). Whether depicted as gay or transvestite, Lincoln adds weight to the new openness toward minority sexual preferences.What of the other, scientific, revolution? Here, too, the Weekly World News brought Lincoln's example to bear. Lincoln had been the subject of an experiment on "Revivitol," a compound designed to bring the dead back to life. Scientists secretly removed Lincoln's Page [End Page 17]

body from his tomb to Walter Reed Army Hospital, where they injected him with the wonder drug, watched his heartbeat and pulse quicken and his body squirm on the table. The former president's eyes opened and, after looking about and asking, "Gentlemen, where am I?" he lost consciousness and died a second time.When the real Lincoln appears, he reflects rather than orients the contemporary mood. In a 1989 tourism advertisement for Springfield, Illinois ( Figure 10), Lincoln is heroic because he delivered the Gettysburg Address without saying "like"; he is also approachable and, above all, cool. No longer is he the remote hero for adoles- Page [End Page 18] cents to emulate; he is an adolescent himself. If his home, law office, and tomb fail to attract, the cool eyewear "relates" Lincoln to students on their senior trip.

Post-1960s representations diminish Lincoln's dignity in many different ways. The Secret Diary of Desmond Pfeiffer (1998) satirizes President Clinton's White House by depicting the Civil War Page [End Page 19] president as a player of telegraph sex. Elsewhere, Lincoln appears for no reason at all, like a postmodern nonsense syllable. Mad magazine shows Alfred Newman throwing a snowball at Lincoln's hat; on Saturday Night Live (1994), Lincoln arises from his Memorial chair and goes berserk after learning about the Republicans' closing down the government. One of the characters in the 1993 film Dazed and Confused senses for a split second that she is having sex with Abraham Lincoln; in another film, Happy Gilmore, Lincoln appears for three seconds in a cloud with the protagonist's dead golf teacher and a crocodile. In yet another absurdist role, Lincoln pitches a baseball to Babe Ruth, who homers with the bat Lincoln had made for him. Lincoln looks into the camera and states, "That's the Babe for ya," and the original story continues. In "Honest Abe and Popular Steve," a thirty-minute television comedy, Lincoln gives a rubdown to a famous rock n' roll star. Here, then, is a new Lincoln portrait—one that exploits celebrity as a source of absurdist comedy.

The imagery of the Internet, the latest medium of Lincoln interpretation, is the most concrete. Hard-Drinkin' Lincoln, a fourteen-episode ( Icebox.com ) series, unveils "the real Honest Abe: a loud, lewd, obnoxious guy in a big hat—the kind of guy you sit behind in a theater and just want to shoot." The episodes follow a common thread, beginning with the theme song depicting "The Great Emancipator" as a chronic drunkard, an "irritator," and "public masturbator." In stories ranging from "Abezilla" to "The Play's the Thing," Abe, belching constantly, makes unkind remarks about his wife ("a nattering scoop of lard" who would never win a wet T-shirt contest), requests sexual favors from beautiful young women ("How about if I put my log into your cabin?"), and reminds Frederick Douglass, "I freed your black asses." Abe is so obnoxious that audiences applaud when Booth shoots him.

Lincoln spoofs are cut from the same cloth as ongoing museum controversies involving "transgressive" art—specifically, artists abusing sacred images (always symbols of Christianity), public officials expressing their indignation, and media readers and viewers shaking their heads in nonjudgmental bemusement. In this connection, the most significant feature of "Hard Drinkin' Lincoln" is that it shares its web site with an equally vulgar series, "Jesus and His Three Brothers." [18] Page [End Page 20]

The lampooning of Lincoln is meaningless if divorced from a public taste conducive to absurdity and ridicule. Juxtaposing greatness and grossness is uncharacteristic of today's Lincoln portrayals, but their irreverence dramatically distinguish them from earlier ones. Hilarious new Lincoln pictures depict nothing in the way of a bond between Lincoln and his admirers, evoke no moral sentiment in them, make no reference to what is lacking in ourselves. These are pictures one expects to see in a disenchanted world, a world in which "the ultimate and most sublime values have retreated from public life," a world whose monuments lack heroes, a world that has lost the pneuma, that breath of life that once welded together great communities to face and conquer great dangers.[19] Inhabitants of this world, we recognize vaguely what the older images symbolize; we know they are authentic, even vaguely heroic, yet they seem alien. We can see them but cannot see ourselves in them. In some inexpressible way, the newer Lincoln images put us into closer contact with ourselves. How seriously, then, should we take Lincoln? Is he still Savior of the Union? Great Emancipator? Man of the People? Yes, but can't we still have some fun with him?

Why Lincoln Fell

The cultural context of Lincoln's visual portrayals enables us to make sense of his diminished stature. Flattering writings of journalists, biographers, and historians reveal nothing about his status, while negative information appears rarely in any of the media indexing his decline. New York Times articles on Lincoln have diminished in number, but their topics (including commentaries on his life and presidency) remain the same and their content is still positive. Magazine articles on Lincoln (listed in Readers Guide) are scarcer today than they were in the early to mid 1900s, but they, too, are complimentary. The Congressional Record publishes fewer public speeches and editorials about Lincoln than before, but they are uniformly laudatory.

Today, radical scholars still criticize Lincoln for his reluctance to free the slaves and for his wish to colonize all free and emancipated blacks. [20] Psychohistorians make even more serious claims, Page [End Page 21] asserting that Lincoln took the country to war in order to satisfy his own neurotic ambition.[21] The most disparaging Lincoln biographies, however, are the most obscure, while works setting him in the best light are the most popular. Carl Sandburg depicted Lincoln as a homespun all-American in a two-volume work (1926, 1939) that dominated popular biography until the early 1970s. Stephen Oates's Malice Toward None (1977), the most widely read biography of the late 1970s and 1980s, shows Lincoln a veritable saint. In a related work, Oates (1984) adored Lincoln openly, defended him against all criticism, and condemned the government for not making his birthday a national holiday. David Donald's Lincoln (1995) is the most recent best-selling story of Lincoln's presidential skills, while Allen Guelzo's Redeemer President (1999) is a paen to the sublimity of Lincoln's moral sense.[22] High-school textbooks, too, continue to depict Lincoln postively,[23] as do movies, Page [End Page 22] television documentaries, and video. The same medium that demeaned Lincoln in The Secret Diary of Desmond Pfeiffer and trivialized him in Happy Gilmore and Honest Abe and Popular Steve also ennobled him in New Birth of Freedom, Lincoln, The Lincoln-Douglas Debates, and Lincoln at Gettysburg. [24]

Acids of Postmodernity

Lincoln's falling stature does not result from a lack of people to recount his virtues. The Lincoln "establishment," with its thousands of partisan biographers, historians, antiquarians, organizations, and curators, is as influential at the end of the twentieth century as it was at the beginning. "As the twentieth century drew to a close," Merrill Peterson observed, "no other famous American had such a large scholarly complement as Lincoln, so many organizations, publications, and activities devoted to cultivating this resource." [25] Reputational enterprise on behalf of Lincoln continued even while his image in the public mind faded.

That writers depicted Lincoln in the same positive light after the 1960s as before, that historians rated him first or second in every one of their nine presidential greatness polls between 1948 and Page [End Page 23] 1981,[26] means that his declining reputation cannot be explained by change in what we know about him. Rather, the explanation is to be found in change in how we feel about what we know. And this feeling has little to do with Lincoln himself; it results from a change of the context in which facts about him are interpreted. Lincoln may personify the national narrative as certainly as ever and the factual content of that narrative may be as positive and credible as ever, but why is his image less magnetic? Why does it no longer solidify and inspire as it once did?

Since the mentality of late twentieth century America is progressive, skeptical, irreverent, pluralistic, relativistic, and less attached to tradition than ever before, it has begun to liberate the individual from the weight of the past. How, in this context, could the Lincoln images of the 1930s and 1940s be anything but alien? In 1968, the peak year of the decade's cultural revolution, R. J. Lifton observed that absurdity and mockery had become part of the post-World War II lifestyle. Modern "protean" man takes nothing seriously; "everything he touches he mocks"; everything, present and past, he ridicules. [27] The stature of Washington, Lincoln, Wilson, and Franklin Roosevelt was once morally imposing, Robert Nisbet added, "but great as these individuals were, they had audiences of greatness, that is, individuals in large number still capable of being enchanted. How, in all truth, in an age when parody, self-parody, and caricature is the best we have in literature, could any of the above names rise to greatness? ... The instinct to mock the great, the good, and the wise is built into this age." [28] Such is the post-heroic mentality of our generation.

Acids of Multiculturalism

America's growing appreciation of diversity figures prominently in the diminishing of its pantheon. The premise guiding the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education is that when heroes of the dominant community are recognized, members of minority communities are marginalized. "To endorse cultural pluralism," Page [End Page 24] the Association resolved, "is to endorse the principle that there is no one model American." [29] Since the Association's followers agree that Lincoln's idol, George Washington, is but one model American among many, they could not have objected to Susan B. Anthony's countenance replacing Washington's on the new dollar coin. That coin's awkward shape doomed it, but Sacagawea, sometime guide of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, spearheads the United States Mint's second try. Sacagawea's historical role is less than pivotal, but her coin, a product of the politics of recognition, perfectly mirrors "a society preoccupied with the virtue of compassion and cynical about every other. In its careless sloughing off of America's founding figures and ideas, its substitution of sentimentality for any invocation of sacrifice, courage, or fortitude, and its nervous defaulting to the spurious democracy of focus groups, it is indeed a coin for our time." [30] The Sacagawea dollar sloughs off more than the first of America's founders. George Washington, having devoted twenty-five years of his life to the making of the American nation, inspired Abraham Lincoln's imagination. "Washington's is the mightiest name on earth," Lincoln declared. "To add brightness to the sun or glory to the name of Washington is alike impossible. Let no one attempt it. In solemn awe pronounce his name and in its naked, deathless splendor leave it shining on." [31] Would Lincoln have said the same of Sacagawea? Would he have said the same of the singers, actors, athletes, and cartoon characters now occupying our new postage-stamp pantheon? [32] Page [End Page 25]

The present situation should be rightly understood: balkanized preferences have not disunited America politically; they have enervated America culturally. In the end, tribal heroes, too, will lose their appeal, for if the politics of recognition make Sacagawea as worthy of commemoration as George Washington, then the same kind of politics can make another tribal figure as worthy as Sacagawea. For a society to admire all ethnic, racial, and national heroes equally, however, is to esteem none. And the step from the former to the latter is short. When inflation makes the five-dollar bill obsolete, what tribe will supply Abraham Lincoln's replacement?

Conclusion

If depthlessness, derision, and deteriorating moral authority define the context of Lincoln's fall, then their effects must extend to all presidents. On no point does the evidence converge so precisely. While Lincoln's Gallup Poll rating, as noted earlier, fell from 62 to 40 percent from 1956 to 1999, Roosevelt's rating fell from 64 to 24 percent; Washington's, from 47 to 24 percent; Eisenhower's, from 34 to 8 percent. Truman's post-presidential reputation peaked in 1975 at 37 percent, then fell to 10 percent. From 1975 to 1991 Kennedy's rating dropped from 52 to 35 percent.

The significance of these statistics must not be exaggerated. The decline of "grand narratives" and their heroes is demonstrable, but if these narratives have deteriorated as fully as postmodern theorizing suggests, the minority of Americans still revering Lincoln would not be as large as it is. America's historical consciousness has been devitalized by the postmodern turn, but it is neither totally "incredulous," as Lyotard asserted, nor totally bereft of "its functors, its great heroes ... its great goal."[33]

Abraham Lincoln's dignity diminished steeply between 1960 and 1980 but has leveled since then. We do not know whether this plateau Page [End Page 26] will be long term, but we know there is a theoretical floor below which Lincoln's reputation cannot fall. Theoretical floor refers to a limit inherent in the character of nationhood itself. Ernest Renan, a French historian, believed that nations distinguish themselves by what citizens remember about their past. "A nation" is, in fact, "a soul, a spiritual principle. Only two things, actually, constitute this soul, this spiritual principle.... One is the possession in common of a rich legacy of remembrances; the other is the actual consent, the desire to live together, the will to continue to value the heritage which all hold in common."[34] In fact, nations consist of more than their memories; they consist of interdependent citizens, common goals and emotional attachments, boundaries distinguishing natives and foreigners. Common memories are essential to nationhood, however, because they shape the meaning of national experience. Great events, including war and disaster, achieve their deepest significance when seen as part of a national story. To forget that story or to deny its dignity is possible only in a nation that has ceased to cherish its own existence.

Lincoln's place in America's story will grow as the 2009 bicentennial of his birth approaches, but he will never again be adored as intensely as he was during the first half of the twentieth century. Political veneration, as Cooley observed, is a traditional, not a secular, attitude:

Deterioration is materialized in the changing forms of commemorative art. From every statue and bust of Lincoln; every cartoon, print, painting, magazine and calendar illustration; every film, video, television commentary and drama, one drops a plumb line deep into the mentality of the generation from which it arose, gauging that generation's fears and aspirations, assessing the styles of thinking, feeling, and judging to which every other work of art is attached. In the present generation, religious and political icons share a common fate as objects of parody and ridicule. The sacred pictures of yesterday, like Lincoln's images, are today pressed to the service of mockery: Leonardo's Virgin is now represented with cow dung; Jesus now appears with an erection or as a naked black woman; the Cross of Calvary now attains fuller meaning when set in a jar of urine. The moral mediocrity and vast shallowness of the day is summarized in the obsessively cynical art of the day.

Friedrich Nietzsche grasped the essence and function of traditional heroes when he asserted that no person can live purposefully without a horizon of unquestioned beliefs. "No artist will paint his picture, no general win his victory" without commitment to what he does and without loving what he does "infinitely more than it deserves to be loved." [36] Nothing illustrates the point better than what early twentieth-century Americans thought of Lincoln. They imagined him more perfect than he was, and they revered him more than he deserved to be revered. This power of mind, the power to admire, did more than elevate Abraham Lincoln; it attached the generation of the 1930s and 1940s to traditions that gave it endurance and drove it to history-turning achievement.

Today, so many alternative frameworks exist that one can no longer believe in the absolute truth of any one of them. Late-twentieth-century man, "The Last Man," as Francis Fukuyama calls him, "knows better than to risk his life for a cause, because he recognizes that history was full of pointless battles in which men fought over whether they should be Christian or Muslim, Protestant or Catholic, German or French. The loyalties that drove men to desperate acts of courage and self-sacrifice were proven by subsequent history to be silly prejudices." [37] World War II was not fought over silly prejudices, but the loyalties needed to annihilate fascism were Page [End Page 28] rendered superfluous by victory itself—victory so total that the mentality needed to achieve it seems no longer necessary—seems, indeed, irrelevant if not harmful to the new tranquility.

Our loss is twofold: not only do the categories defining heroes and gods lose credibility; heroes also lose the eminence arising from their being compared with gods. Still, the history of religion is replete with successful revivals. Is revival not possible in a disenchanted political realm? [38] To answer this question, we must move beyond the evidence of art into the realm of speculation.

Enchantment, as Bruno Bettelheim observed, reduces anxieties by investing them in stereotyped characters, such as those we find in fairy tales. As these characters are deified and demonized, social boundaries become more rigid. [39] The logic convincing people that George Washington told no lie and Abraham Lincoln raised himself from poverty solely by his own powers also led them to believe that blacks are totally shiftless, Jews uniformly crafty, Irish absolutely unruly. Stemming from the same logic, hero worship and ethnic prejudice grow and diminish together.

The enchanted world that made Lincoln godlike was a Victorian world of moral and hierarchical distinctions, one whose heroes were utterly different from the average run of men. Out of the recent disenchantment of that world arose fresh historical perceptions. Meanness, weakness, and fault were seen in men once deemed flawless, and as the dualism that once distinguished great men from ordinary men could now be recognized in all men, the line between greatness and commonness blurred. Concurrently, a new generation of social scientists asserted that traditional distinctions between heroes and villains resulted from artificial bound- Page [End Page 29] aries sustained by conservative elites and interest-driven "silent majorities" rather than natural variations of moral character and personality.[40] As political and social boundaries eroded together, everyone seemed the same. Men and women, whites and blacks, ethnics and WASPs, Christians and Jews, gays and straights, rich and poor, parents and children, teachers and students, authors and readers, criminals and victims, sinners and saints—the distinctions seem less absolute than ever before.

In this context, inequalities became more oppressive as they diminished. News media indignantly broadcast stories of bias and meanness. Academic disciplines changed directions. "The New History," reaching beneath "the ruling class" to explore the world of the ordinary man and the underdog, has a place for everyone, including Abraham Lincoln, but its main concern is to describe the past "from the bottom up, in retaliation for years of history from the top down."[41] The same penchant for equality that initially elevated Abraham Lincoln eventually lessened the acceptability of his preeminence.

Americans who think about Lincoln have a sense that he cannot be forgotten, that their privileges and comforts are somehow built upon his gains and sufferings. Yet, they feel even more keenly that Lincoln's heroic achievements, however memorable, were not quite heroic enough. They seem to have split the difference. Amid a veritable renaissance of biography and television documentaries, they have made Lincoln an object of quiet reverence and temperate admiration—in line with America's quieter religious faith and maturer patriotism. The new Lincoln serves a new kind of people—non-ideological, non-judgmental, present-oriented, fair-minded, at peace with themselves, good humored, in need of neither great heroes nor great villains.

Better historiography or more attractively packaged artifacts cannot reawaken the ancient need for heroism and villainy. Lincoln's decline, no less than that of his predecessors and successors, has nothing to do with historiography; it is part of the fraying fabric of American nationhood and self-esteem. The contemporaneity of Page [End Page 30] the past has been lost, and analytic historians are the last persons we would expect to restore it. True, Abraham Lincoln's representations are very much part of the present and will be more so during his 2009 bicentennial, but their function is no longer to forge the mentality of our generation. Here, precisely, resides the peril: as Americans cease to believe in the sanctifying fullness of the past, they lose sight of the existential link between their present life and the transformations wrought by their forebears; they lose sight of themselves as historical beings, forget that they have inherited, not created, the most valuable of their possessions.

That the American people might soon identify with the past and its heroes as closely as they did before the cultural revolution of the late twentieth century is doubtful. Culture, after all, does not come a la carte. If anyone is to be revered today as deeply as Abraham Lincoln was six to seven decades ago, then we must go back to a morally bounded state of strong institutions, uncompromising commitments, and invidious social distinctions. Such a restoration does not appear on the horizon. Even if some great crisis should befall the nation, it would be faced by a generation taught that America is no better than most countries and worse than some, that its great men were admirable but imperfect, that its great events were as much episodes of oppression as inspiration, that the elevation of any man diminishes everyone else by implication or, even worse, by design.

This perspective, although powerful today, is difficult to sustain over the long run. When the postindustrial-postmodern ethos and worldview weaken, as they must, it will be impossible to deny either the historical ordering power of the American Civil War, the indispensable pivotal role of Abraham Lincoln, and their influence on subsequent events. Presently, historians and textbook writers qualify their regard for traditional heroes and refuse to allow any one man to monopolize the national pantheon. What, then, is to be said of Abraham Lincoln? He is no longer America's singular model. Yet, how can the man who contributed most to the realization of American democracy be no better than other men? The question itself may be irrelevant.

Lincoln's historical achievements are beyond question, but has not the egalitarianism that reduced Lincoln's prestige also made our society more just and decent than ever before? Has America ever been freer of religious, ethnic, and racial hatred? Has it ever been more worthy of the love of all its citizens? Merely to ask the question is to affirm Abraham Lincoln's ironic place at the millennium. Page [End Page 31]

Notes

-

New York Tribune, Apr. 19, 1865, 4.

-

Richard Terdiman, Present Past: Modernity

and the Memory Crisis (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press,

1993), 3.

-

This and all subsequent figures include "don't

know" responses in their computations.

-

Barry Schwartz and Howard Schuman, "Abraham

Lincoln in the American Mind: First National Survey, 1999" (paper

presented at Conference on Abraham Lincoln, Decatur, Illinois, June

2000). Survey conducted by University of Maryland Survey Research

Center, Project #1367, June 1999.

-

Barry Schwartz, "Postmodernity and Historical

Reputation: Abraham Lincoln in Late Twentieth-Century American

Memory," Social Forces 77 (1998): 63–102.

-

The number of Reader's Guide articles

rose from 1910 (following the 1909 centennial of Lincoln's birth)

to 1960—a fifty-year period—then dropped sharply.

During the 1930s, an annual mean of 17 articles appeared; during

both the 1940s and 1950s the mean stabilized at 25 articles, then

dropped to 14 articles during the 1960s, then to 7 and 8 articles

during the decades of the seventies and eighties, and to 11

articles from 1990 to 1998. The Congressional Record Lincoln

entries, like the Reader's Guide and Times, rose

rapidly from 1910 to annual means of 17, 23, and 29 entries during

the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s; however, the Record's entries

on Lincoln did not fall during the 1960s because it reported on

1961–1965 Civil War Centennial activity, which stirred little

interest among most newspaper and magazine editors. The yearly mean

of 41 entries appearing in the Record through the 1960s fell

during the seventies and eighties to 12, and from 1990 to 1996 to

6. For further discussion, see Schwartz, "Postmodernity and

Historical Reputation," 72–75.

-

Visitation statistics are drawn from the

National Park Service's Public Use of the National Parks: A

Statistical Report. The six reports cover the periods

1904–40; 1941–53; 1954–64; 1960–70;

1971–80; 1981–92. Local visitation statistics were

provided by site managers at Hodgenville, Kentucky; Gentryville,

Indiana; New Salem (Petersburg), Illinois; and Springfield,

Illinois.

-

Clifford Geertz, "'From the Native's Point of

View': On the Nature of Anthropological Understanding," in Local

Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology (New

York: Basic Books, 1983), 58.

-

Lewis A. Coser, ed., Sociology Through

Literature (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1963), 2.

-

Charles Horton Cooley, Human Nature and

the Social Order (1902; reprint, New York: Schocken, 1964),

116–17.

-

Otto Fenichel, Collected Papers, vol.

1 (New York, W.W. Norton, 1953–54), 393.

-

The resemblance to Henry Ford may or may not

have been deliberate.

-

Maxwell Geismar, 1941, cited in Charles C.

Alexander, Here the Country Lies: Nationalism and the Arts in

Twentieth-Century America (Bloomington: Indiana University

Press, 1980), 154.

-

Robert Penn Warren, The Legacy of the

Civil War (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961),

78–79.

-

Richard Merelman, Making Something of

Ourselves: On Culture and Politics in the United States

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 30.

-

Edward A. Shils, Tradition (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1981), 32–33.

-

Charles E. Morris III, "My Old Kentucky

Homo: Lincoln and the Politics of Queer Public Memory," in

Framing Public Memory, ed. Kendall Phillips (Tuscaloosa:

University of Alabama Press), 2003. Gabor Boritt affirms the

relevance of the issue in his editorial introduction to The

Lincoln Enigma: The Changing Face of an American Icon (New

York: Oxford University Press, 2000), xiv–xvi.

-

See also "The Hideous Jabbering Head of

Abraham Lincoln," located on another website of the same name. The

headline: "I was the President of the United States of America back

when it was cool to be President, instead of now, which is just

lame."

-

Max Weber, "Science as a Vocation," in

From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, ed. Hans Gerth and

C.Wright Mills (New York: Oxford University Press, 1958), 155.

-

For a summary, see Don Fehrenbacher,

Lincoln in Text and Context: Collected Essays (Stanford,

Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1987), 207–8. For a more

recent statement, see Lerone Bennett, Jr., Forced Into Glory

(Chicago: Johnson Publishing, 2000).

-

Edmund Wilson's Patriotic Gore: Studies

in Literature (New York: Oxford University Press, 1962) set the

stage. He believed that when Lincoln warned his Springfield

audience against men of towering genius who cannot stay on the

beaten path but seek instead dictatorial power, he was

unconsciously describing himself. Seventeen years later, George

Forgie's Patricide in the House Divided (New York: W.W.

Norton, 1979) argued that Lincoln resented the founding fathers

because they stood in the way of his quest for fame. Projecting his

aspiration upon Stephen Douglas and the leaders of the South,

Lincoln needlessly took his country to war. Dwight Anderson's point

in Abraham Lincoln: The Quest for Immortality (New York:

Knopf, 1982) is essentially the same: Abraham Lincoln starts a war

to satisfy his own neurotic ambition. In the African American

press, Lincoln's racism and efforts to deport the slaves he freed

were strongly condemned (see, for example, Lerone Bennett, "Was Abe

Lincoln a White Supremacist?" Ebony 23 (1968): 36–37;

Julius Lester, Look Out, Whitey! Black Power's Gon' Get Your

Mama! (New York: Dial Press, 1968).

-

Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The

Prairie Years, 2 vols. (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1926);

Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, 4 vols. (New York: Harcourt,

Brace, 1939); Stephen Oates, With Malice Toward None: The Life

of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Harper & Row, 1977);

Abraham Lincoln: The Man behind the Myths (New York: Harper

& Row, 1984); David Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon

& Schuster, 1995); Allen Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer

President (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1999). Also, Harry

Jaffa's philosophical study, Crisis of the House Divided

(New York: Doubleday, 1959), affirms the authenticity of Lincoln's

egalitarianism, while Don Fehrenbacher's Prelude to

Greatness (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1962)

reveals the depth of his antislavery convictions. LaWanda Cox's

Lincoln and Black Freedom (Columbia: University of South

Carolina Press, 1981) and Peyton McCrary's Abraham Lincoln and

Reconstruction (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press,

1978) carry forward Fehrenbacher's and Jaffa's vision of Lincoln's

idealism.

-

When college freshmen were asked (over a

thirteen-year span) to name the figures who most often came into

their mind in connection with American history, Lincoln was the

second to third most frequently mentioned, after George Washington

and Thomas Jefferson. See Michael Frisch, "American History and the

Structures of Collective Memory: A Modest Exercise in Empirical

Iconography," Journal of American History 75 (1989):

130–56.

-

The best inventory of Lincoln-related

movies, television programs, and videos is Mark S. Reinhart's

Abraham Lincoln on Screen: A Filmography, 1903–1998

(Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1999). See also Frank Thompson,

Abraham Lincoln: Twentieth-Century Film Portrayals (Dallas,

Tex.: Taylor, 1999). For additional information, including a

benchmark for assessing the great diffusion of Lincoln dramas and

documentaries, see The Civil War in Motion Pictures (U.S.

Library of Congress, n.d.) and Variety Television Reviews.

Most of the 29 films featuring Lincoln and appearing between 1910

and 1919 were twenty-to-thirty-minute reels shown in storefront

nickelodeons. In contrast, 9 of the 16 films produced between 1920

and 1939 were feature-length (one and a half hours or more) and

shown in movie theaters. Full-length films about Lincoln were

produced for mass audiences during the twenty-year period 1920 to

1940. (The last film in this category was Abe Lincoln in

Illinois.) Since 1940, Lincoln films have been produced for

schools and museums but not movie theaters. No medium of

communication, however, has brought Lincoln to the attention of

more people than television. During the 1950s, Lincoln was featured

in 9 films and 22 television programs. During the 1990s, he

appeared in 17 television programs and 19 video features, some for

educational institutions; others for home use.

-

Merrill D. Peterson, Abraham Lincoln in

American Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 375.

See also G. Cullom Davis, "Popular Legacies of Abraham Lincoln,"

Detours (online magazine), November 16, 2000 ( www.prairie.org/detours/lincoln/index.asp

). For more general discussion of "reputational enterprise," see

Gary A. Fine, "Reputational Entrepreneurs and the Memory of

Incompetence: Melting Supporters, Partisan Warriors, and Images of

President Harding," American Journal of Sociology 101

(1996):1,159–93. See also Gladys and Kurt Lang, Etched in

Memory: The Building and Survival of Artistic Reputation

(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990).

-

Dean Keith Simonton, Why Presidents

Succeed: A Political Psychology of Leadership (New Haven,

Conn.: Yale University Press, 1987), 182–83; Robert K. Murray

and Tim H. Blessing, Greatness in the White House: Rating the

Presidents (University Park: Pennsylvania State University

Press, 1994).

-

Robert J. Lifton, "Protean Man," Partisan

Review 35 (1968): 22.

-

Robert N. Nisbet, The Twilight of

Authority (New York: Basic Books, 1975), 109–10.

-

American Association of Colleges for Teacher

Education, "On One Model American: A Statement on Multicultural

Education," Journal of Teacher Education 24 (1973):

264–65.

-

Michael J. Lewis, "Of Kitsch and Coins,"

Commentary 108 (October, 1999): 36.

-

Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works

of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers

University Press, 1953–1955), 1: 279.

-

The Americans most commonly commemorated on

postage stamps during the first two decades of the twentieth

century (75.1 percent of the total) were political figures,

statesmen, and men engaged in the governance of the country,

including Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, Andrew Jackson,

Henry Clay, and Abraham Lincoln. Military figures and individuals

engaged in the discovery, exploration, and settlement of the New

World account together for 14.2 percent of the total, the remaining

10.7 percent consisting of "symbolic women," an awkwardly named

category consisting of presidents' wives. As we move to the last

two decades of the century, the number of political figures,

statesmen, and men engaged in the governance of the country drops

from 75.1 percent to 28.8 percent while a new category consisting

of entertainers, appearing for the first time in mid-century, makes

up 28.7 percent of the total. If sports figures are added to this

list, then the percentage rises to 33.1 percent. (Barry Schwartz,

"Collective Memory and Multiculturalism," Unpublished manuscript,

2002.

-

Jean-Francois Lyotard, The Postmodern

Condition, trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984); originally

published as La condition postmoderne (Paris: Éditions

de Minuit, 1979), xxiv. The continuing relevance of grand

narratives and commemorative symbols is evident in ongoing debates

over cultural diversity. Multiculturalists, themselves products of

postmodernity's aversion to boundaries and differentiation, see a

hegemonic national memory alienating people from their own ethnic

communities, traditions, and petit narratives. Critics charge that

multiculturalism itself promotes alienation by undermining shared

traditions and the grand historical narrative that once unified an

ethnically diverse nation. (See Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The

Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society

(New York: W.W. Norton, 1993).

-

Ernest Renan, Oeuvres Completes, vol.

1 (Paris, France: Calman-Levy, [1888], 1947), 903 (Definitive

edition assembled by Henriette Psichari.).

-

Cooley, Human Nature and the Social

Order, 314. See pp. 312–16 for discussion of

socialization, emulation, and hero-worship.

-

Cited in Francis Fukuyama, The End of

History and the Last Man (New York: Avon, 1992), 306.

-

Ibid., 307.

-

As Lincoln's bicentennial anniversary

approaches, might we hope for a resurgence of 1909 centennial

admiration? Or will the 2009 bicentennial resemble instead the

bland 1959 sesquicentennial? In 1909, great throngs appeared in the

streets, schools, and public and private meeting places to observe

the Lincoln centennial. The sesquicentennial paled in comparison.

When the Sesquicentennial Commission requested state governors to

establish state commissions, only nineteen (all of which were

Northern) complied. Most state and local organizations did arrange

special features to supplement their regular Lincoln Day

observances while the federal government added its own touches,

including commemorative stamps and a new back for the Lincoln

penny; however, Americans celebrated the centennial by watching

their congressional representatives at a one-hour televised

joint-session in the Capitol. Their forebears had turned out in

massive number to celebrate it themselves.

-

Bruno Bettelheim, The Uses of

Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (New

York: Knopf, 1977).

-

Representative readings in labeling theory

can be found in Earl Rubington and Martin S. Weinberg, eds.,

Deviance: The Interactionist Perspective (New York:

Macmillan, 1999).

-

Kenneth L. Ames, "Afterword: History

Pictures Past, Present, and Future" in Picturing History,

American Painting, 1770–1930, ed. by William Ayres (New

York: Rizzoli, 1993), 225. See also Eric Foner, The New

History (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990).

![Figure 10. Courtesy of Nicky Stratton, Springfield

[Illinois] Convention and Visitors Bureau.

Figure 10. Courtesy of Nicky Stratton, Springfield

[Illinois] Convention and Visitors Bureau.](/j/jala/images/schwartz_fig2410a.jpg)