Holland's Informants: The Construction of Josiah Holland's 'Life of Abraham Lincoln'

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abraham Lincoln's coffin had lain in the receiving vault in Springfield's Oak Ridge Cemetery for less than three weeks when a dapper, walrus-mustachioed New Englander stepped off the train and checked into Springfield's St. Nicholas Hotel. He was Josiah Gilbert Holland, one-time editor (and still part owner) of the Springfield, Massachusetts, Republican, a nationally popular writer of advice books, and (what would turn out to be most memorably) part of a small circle of admirers and encouragers of an unknown Amherst poet named Emily Dickinson. None of those attributes, however, provided the slightest qualification for the task that brought him to the Illinois namesake of his hometown, which was the writing of a biography of Abraham Lincoln. Holland had not known Lincoln personally—had never even met him casually. Notwithstanding those deficits, Holland produced a landmark Lincoln biography, the first of any substantial length as a biography, the first with any aspirations to comprehensiveness, and a best-seller of 100,000 copies that was published in several languages. It was precisely his lack of personal acquaintance with Lincoln that brought him to Springfield ("in search of original and authentic material for the work"), and he came away with some of the most important informant materials any early Lincoln biographer would gather. [1] Holland would use them to create the first life of the "inner Lincoln," setting the stage for a genre of Lincoln studies that remains compelling and fruitful to this day and producing a biography that Paul Angle ranked "by far the best" of the early Lincoln biographies.[2] Page [End Page 1]

And yet, Holland's Life of Abraham Lincoln remains one of the least well-respected of the Lincoln biographies, even among the controversial crop of post-assassination "lifes" by the biographers of the first generation after Lincoln's death. Benjamin P. Thomas wrote off Holland for his "mawkish sentimentality" and for being a "moralist" who "irritated" Herndon from the beginning. [3] Roy Basler acknowledged that "Holland added much to what was known" about Lincoln, but added with damning certainty that Holland was so preoccupied with eulogizing Lincoln that "Facts out of keeping with eulogy are excluded from its pages." [4] David Donald, in his biography of Herndon, sniffed obliquely at Holland as "a literary old maid with a passion for prettifying and tidying," and in Lincoln Reconsidered, Donald accused Holland of manufacturing "a mythological patron saint."[5] Some of the most important Lincoln biographers of the past quarter-century do not cite Holland or Holland's informant material at all, while the first volume of Herndon's Lincoln reads (by comparison with Holland's Life) as though he were trying to avoid any recognition that Holland or his informants had ever existed—despite that in numerous cases, Herndon's own informants had originally been Holland's. Herndon, in fact, was Holland's greatest detractor: to Herndon, Holland's Life was "romantic" and "all mere bosh, a lie."[6]

Admittedly, Holland was an easy target for skepticism. Despite Holland's best efforts at "collecting materials for his life of President Lincoln," he failed to deal with some of the most obvious sources—Mary Todd Lincoln and her sons, the Lincoln cabinet—and fell into the uncritical trap of accepting from others, like Usher F. Linder, anecdotes of Lincoln's life that were easily recognized as impossible (such as Lincoln's supposed visit with Henry Clay in 1847). [7] He was, for another thing, an easterner, and as Merrill Peterson has pointed out, "Lincoln's old friends and companions Page [End Page 2] in Illinois were reluctant to surrender his fame to eastern men of letters like Holland," especially since a number of them were contemplating Lincoln biographies of their own and resented Holland's easy preemption of their ambitions. [8] He made himself even more vulnerable by dropping the Lincoln subject almost as soon as his Life of Abraham Lincoln was published in early 1866, and thus giving himself no room for further work or for contesting his title as a biographer with other competitors. Holland returned to the world of journalism without a backward glance at Lincoln, except an occasional review and a sharp disparagement of Lamon and Herndon on the pages of Scribner's Monthly after Lamon's Life appeared in May 1872. Lacking the threat implicit in follow-up volumes or extended research, Holland was fair game for the increasingly possessive fraternity of Lincoln intimates who wished to claim Lincoln biography as their rightful territory.

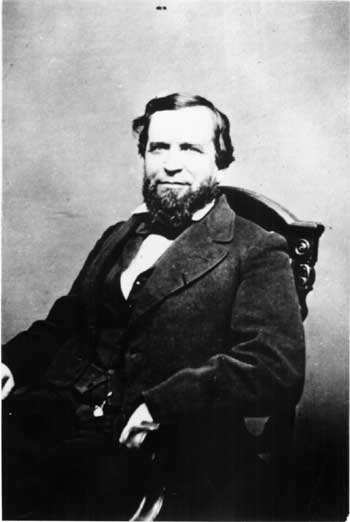

Perhaps the greatest liability Holland labored under was simple credibility—not that he couldn't be believed, but that it was hard to believe that what a journalist like Holland would write about Lincoln would rise in any significant way above the hack-work biographies by Joseph H. Barrett, John Locke Scripps, William Dean Howells, or Henry J. Raymond. Born in Massachusetts in 1819 to poverty-stricken ultra-Calvinist parents, Holland's whole life had been a Lincolnesque struggle to pull himself up into respectability. [9] His principal success, after several misstarts, came in 1849 when he was hired by Samuel Bowles, the owner and editor of the weekly Springfield Republican, as an assistant editor and general copywriter, and from then on, Holland went from strength to strength. While Bowles ran the business side of the Republican, Holland "added to the paper a higher literary tone, and a broader recognition of human interests." Bowles's biographer remarked that Holland "was eminently a man of sentiment and feeling," which was a faintly critical way of saying that Holland tended to play for the grandstands with melodramatic human-interest angles. Although he gradually abandoned the evangelical fervor of his parents for a bland liberal Congregationalism, Holland still aspired to religious respectability.[10] He had no "particular interest" in "Christianity, in Page [End Page 3] the form of abstract statement and in the shape of a creed," and if someone's beliefs "seem good and true and like Christ, it satisfies me, and nothing else does." [11] What Emily Dickinson most admired in Holland was that he was "so simple, so believing" and made God seem "so sunshiny."[12] Still, even if he was more a moralist than an evangelist, "in his bearing there was something a little suggestive, as it were, of gown and bands,—a touch of self-consciousness," and he wore his moralism so much on his sleeve that later memoirists often found it necessary to remind their readers that Holland was not, in fact, an ordained clergyman.[13]

His success with the Republican fueled his ambitions to literary grandeur, and in 1855 he published the first of twenty-two books, which would eventually include an assortment of local history, historical fiction, and some particularly vacuous but instantly popular advice books on how to make a proper success of oneself. All told, his book sales topped over 500,000 copies in his lifetime, and by 1857, he was able to sell his interest in the Republican (although he kept his hand in writing for it and temporarily assumed the editorship while Bowles was in Europe during the Civil War) and take to the lyceum circuit.

None of this helped purchase the slightest standing with the reigning American literati or helped sponge away the stain of hack journalism.[14] But what these books did give Holland was celebrity, and celebrity was what was probably behind the lone qualification Holland had for writing a biography of Abraham Lincoln, since there is no other discernible reason for why Holland was asked to deliver the eulogy at the Springfield city memorial observances on April 19, 1865, four days after Lincoln's death. For someone who had never known Lincoln, the Springfield, Massachusetts, eulogy turned out to be a remarkably shrewd appraisal of Lincoln's character. "From the first moment of his introduction to national notice, he assumed nothing but duty," Holland began, "I do not think that it ever occurred to Mr. Lincoln that he was a ruler. More emphatically than any of his predecessors did he regard himself as the servant of the people ..." This was, as it turned out, almost exactly how Lincoln himself often tried to define his presidency, Page [End Page 4] and it rang true to Holland's hearers. And despite the later detractors of his biography, Holland made no attempt to prettify Lincoln. "Unattractive in person, awkward in deportment, unrestrained in conversation, a story-lover and a story-teller, much of the society around him held him in ill-disguised contempt." But the greatness of Lincoln lay in how the contempt "never seemed to generate in him a feeling of revenge, or stir him to thoughts or deeds of bitterness." What showed how much Holland was relying on journalistic instinct was his contention that Lincoln "was a Christian ..." Especially it was at Gettysburg "while standing among those who had laid down their lives for us, that he gave his heart to the One how had laid down his life for him." Yet, this was almost the only wrong step Holland made. He hailed Lincoln as the military genius of the war; as "the liberator of a race"; but especially he hailed him as an example of how inner character lays the foundation for external action and greatness. "I do not know where in the history of mankind I can find so marked an instance of the power of genuine character and the wisdom of a truthful, earnest heart, as I see in the immeasurably greater results of Mr. Lincoln's administration."[15]

The success of the eulogy led within a few weeks to a proposal that Holland write a biography of Lincoln, which Samuel Bowles would market by subscription. Holland rose to the challenge, making his whirlwind visit to Springfield, Illinois, in May 1865 and thoroughly pillaging four major Lincoln sources: the 1860 campaign biographies of Scripps, Barrett, and Raymond (and revisions of Scripps such as D. W. Bartlett's The Life and Public Services of Hon. Abraham Lincoln), plus the expanded editions of these biographies, which appeared in 1865 shortly after Lincoln's death (Raymond's The Life and Public Services of Abraham Lincoln and Barrett's Life of Abraham Lincoln) [16]; the serialization of Francis Carpenter's Six Months At the White House in the New York Independent and Noah Page [End Page 5] Brooks's "Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln" in the July 1865 issue of Harper's New Monthly Magazine; William M. Thayer's The Pioneer Boy, and How He Became President (1863), which Holland rightly appraised as containing more informant material than its breezy, semi-fictional style might suggest[17]; and the numerous letters and interviews he had been able to collect from direct informants. Holland and Bowles issued an advertising circular for the book in December. By February 1866 it was ready to be mailed out to its purchasers.

Not surprisingly, although the biography stretched out to 544 closely printed pages, many of the same themes that inhabited the eulogy reappear in the Life, and some of them with the same faults. Lincoln, in Holland's hands, is always antislavery, and emancipation is the great goal he was always aiming at, though always as a gradualist (and not with the ill-tempered spite of the Radicals). "Sudden emancipation was never in accordance with Mr. Lincoln's judgement," Holland believed, "Nothing but the necessities of war would have induced him to decree it with relation to the slaves of any state." The Radicals were "a damage to the national cause," and the Wade-Davis manifesto "an offensive paper." Holland's Lincoln is also unquestionably a Christian, who, although he "always remained shy in the exposure of religious experiences," nevertheless "found a path to the Christian stand-point—that he had found God, and rested on the eternal truth of God." This made Lincoln, in Holland's estimate, a "true Christian, true man."

Yet, reticence is not a Christian virtue, and Holland's need to explain how Lincoln could have been a "true Christian" without giving any public relation of his religious experiences—without ever joining a church—led Holland into an examination of the third theme of the eulogy, the inner character of Lincoln. It was there that Holland had his most original contribution to make: his need to explain the "double life" of a man who was religious but not Page [End Page 6] apparently religious led Holland to portray Lincoln as psychologically complex, as contradictory and paradoxical, as almost two men, one the surface politician, the other a hidden Lincoln. Lincoln was, in Holland's estimate, a product of the frontier, but one who early withdrew from the frontier's vices; he was oppressed with melancholy and yet capable of laughing "incontinently over incidents and stories that would hardly move any other man in his position." He was "not endowed with a hopeful temperament," Holland believed, "He had no force of self-esteem—no faith in himself that buoyed him up amid the contempt of the proud and prosperous."

This was cutting surprisingly close to the bone for a man who had never made Lincoln's personal acquaintance. Much of this insight was clearly owed to Herndon, who would make the psychological complexity of Abraham Lincoln the cornerstone of his 1866 lectures on Lincoln and his later collaborative biography with Jesse Weik. The idea that Lincoln had been more than met the eye, that he was possessed by melancholy—these were already conclusions Herndon was coming to as he conducted his own research into Lincoln's early life in 1865 and 1866. Yet there was one point on which Herndon and Holland could not have differed more enormously, and that was the inclusion of religion in that complexity. Not only was Lincoln in no sense a professed Christian, argued Herndon, but Holland had deliberately manufactured a Christian Lincoln to make a better story out of his complexity. Herndon complained in 1882 to Isaac N. Arnold, who was then writing his own Life of Lincoln,

What has to be weighed in the balances against Herndon's animus, and against the contempt and neglect of modern Lincoln biographers flowing downstream from Herndon, is the underappreciated degree to which Holland attempted to plant himself on the foundation of informant testimony—much of it, in fact, from sources Herndon himself would later turn into his own informants, and not a little of it coming from Herndon himself. Although Holland never compiled anything close to the massive three-volume "Lincoln Record" that Herndon assembled, and although Barrett, Thayer, and Scripps all, in varying degrees, employed informant testimony more than has been suspected, Holland was the first whom we know for certain spoke directly, or by letter, with much of the main cast of characters who were afterward to become famous (or notorious) as Lincoln informants. [20] This list includes John Hanks, Dennis Hanks, Albert Hale, Stephen Logan, Jesse Dubois, Usher F. Linder, Newton Bateman, Augustus H. Chapman, George Boutwell, Anson Henry, Joshua Speed, John D. Defrees, Orville Hickman Browning, David Davis, and Erastus Wright, as well as New Salemites, including "Uncle Jimmy" Short and Henry Onstott. [21] Page [End Page 8]

The first and the most significant of these informants was Herndon, to whom Holland made a direct line as soon as he arrived in Springfield, and who was originally far more enthusiastic about Holland's project than he ever afterward liked to admit. Herndon, who considered himself in cultural terms to be "turned New-Englandwards," welcomed Holland in May 1865 to Springfield, and "quit for that period" Holland was in Springfield "his profession" in order to answer Holland's numerous questions about Lincoln's pre-presidential life. Herndon had already been toying with the "intention to write & publish the subjective Mr. Lincoln ... giving him in his passions-appetites-& affections = perceptions-memories," but his ambitions at that point extended to no more than a "pamphlet" of "50 or 75 pages" (in other words, the Lincoln lectures Herndon delivered in Springfield in 1865 and 1866). [22] Holland was after a more substantial biographical prize than a pamphlet, but he shared Herndon's interest in Lincoln's inner life, and Herndon seems to have turned the spigot of reminiscence on full for the New England journalist. "I have helped Doctor Holland to some of the facts of Lincoln's life, many in fact," Herndon acknowledged twenty years later. To Ward Hill Lamon in 1870, he grudgingly conceded that "There is much in Holland's Life of Lincoln which is true, as I gave him much, though he did not record what I said correctly." [23] Among the materials and reminiscences Herndon appears to have shared with Holland were Herndon's recollections of Lincoln's descriptions of his mother—Herndon's attribution to Lincoln of the comment, "All that I am or hope to be I got from my mother, God bless her!" was first reported in Holland[24]—some of the most familiar stories of the Lincoln legal practice, including the Revolutionary widow's pension case and the Matson (or "Matteson," as Holland spelled it) slave case, and at Page [End Page 9] least one Lincoln letter from 1849 on land office patronage. In particular, Holland's account of Lincoln's second political career from 1854 until the presidential nomination in 1860 shows Lincoln very much through Herndon's eyes. (In fact, Holland's omission of significant political events, such as the Decatur nominating convention in 1860, may be explicable only on the realization that Herndon did not attend the Decatur convention, and had no account of his own to give to Holland). Far from the hostility that would sour his later comments on Holland, Herndon's only regret at that time was that Holland "could not have been with me 8 or 10 days Consecutively." [25] In fact, Herndon's first research trip "down to Menard County," where he collected the beginnings of his own informant testimony, may have originally been undertaken, at least in part, at Holland's prompting. [26]

Herndon performed an equally important service for Holland by putting him in touch with several local Lincoln acquaintances, including Usher F. Linder, Erastus Wright, and Albert Hale, the pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church. Given the limitations on Holland's time, the journalist's method seems to have been to take down reminiscence material on the spot, but to leave a request for a follow-up letter which would allow the informant an opportunity to respond to certain questions or recollect further details. Albert Hale wrote to Holland on June 22, 1865, heading one reminiscence, "The story you desired me to write out is as follows ...," followed with an unusual account of Lincoln performing itinerant farm work in Sangamon County just prior to building the flatboat he and John Hanks took to New Orleans for Denton Offut in 1831.[27] Similarly, Holland reported to Herndon that "I had a long talk" with Usher F. Linder "of which I took notes," and Linder then subsequently sent to Holland an expansion of his comments. (Unfortunately, what Linder sent Holland, and which Holland accepted, was an account of the apocryphal dinner of Henry Clay and Lincoln in Kentucky in 1847). [28] Page [End Page 10]

The biggest, and most controversial, jackpot Holland hit from these Springfield interviews came from Newton Bateman, the Illinois superintendent of public instruction, who recounted for Holland an interview with Lincoln in the fall of 1860 in which Lincoln made a profession to Bateman of the truth of Christianity:

In some cases, Holland commissioned his informants to take one further step and contact others on his behalf for still more informant material. Albert Hale not only called on an early farm employer of Lincoln's, but cross-checked the likely date of the farmer's recollections with Herndon, and promised to consult the county probate files "if he is mistaken." [31] Holland's most useful commission went to Erastus Wright, a Springfield real-estate developer and abolition activist. Wright is best known, thanks to Herndon, as the notorious agent in Lincoln's Revolutionary War widow's pension case in 1846.[32] It is not difficult to see why Wright left an unpleasant taste in peoples' mouths. Wright was Holland's most persistent informant, but he clearly took every opportunity to bask in the reflected glory of "My old Neighbor Abraham." (With unconscious cheek, he sent Holland his photograph "that you may remember me when I cast up in Springfield Mass." and seriously proposed that Holland Page [End Page 11] look in on Wright's Springfield, Massachusetts, relatives on his return to New England). [33] Yet Wright was invaluable to Holland as a Springfield contact for informant material. Wright was able to quote material on Lincoln from a diary he had kept as far back as 1831.[34] He also was responsible for introducing Holland to Newton Bateman, and even more dramatic, it was Wright who went on Holland's behalf to Chicago in early June 1865 to attend the United States Sanitary Commission Fair and to interview two informants who would later become major figures in the whole tapestry of Lincoln informants, John Hanks and Dennis F. Hanks.

Both of Lincoln's Hanks cousins had actually been trading on their connections with their celebrated relative all through his presidency, and in June 1865, both of them were to attend the Sanitary Fair in Chicago as a pair of living exhibits along with the original Lincoln family cabin in Illinois, picked up from near Decatur and reassembled at the Fair. It is not clear who tipped Holland to the potential of the Hanks cousins as informants, but it was Wright whom Holland commissioned to interview them in Chicago, and Wright "went up to Chicago twice" for Holland "to get more fully Lincolns biography" from the Hankses.[35] Dennis Hanks, as he would for Herndon, proved for Holland to be a cornucopia of material on Lincoln's early life. From his interview notes, Wright assembled for Holland a fifteen-hundred-word narrative outline that itemized Lincoln's antecedents back to Virginia, established the time of the Lincoln migration to Kentucky, the marriage of Lincoln's parents and their move to Indiana and the "half faced Camp," Denton Offutt's hiring of Lincoln and the flatboat voyage to New Orleans, and the Black Hawk War and Lincoln's entry into politics. All this, Wright assured Holland, "all Illinoisans yea the Country will like to hear."[36] Page [End Page 12]

The Hankses were not the only Lincoln informants Wright pursued. In early July, following Herndon's own first sweep through Menard county, Wright set up interviews with two old New Salemites, "Uncle Jimmy" Short and Henry Onstott. Short confirmed the Hanks's accounts of the Offut flatboat and the Black Hawk War, and added his own recollection of buying Lincoln's impounded "Compass and Surveying apparatus" for him. Short also fleshed out the Hanks's recollections with images of Lincoln "Studying Law by himself" between 1832 and 1836, studying "English Grammar" with Mentor Graham, and generally "telling Stories, and all proper amusements, cheerful, and full of Highlarity and fun which made him Companionable and rather conspicuous among his associates." Henry Onstott recalled that the first time

Oddly, Holland chose not to use one piece of informant testimony from "Uncle Jimmy" Short which would, in Herndon's hands, become one of the most violently argued aspects of the Lincoln legend, the Ann Rutledge romance. [37] As Short told Wright,

In addition to commissioning interviewers, Holland also advertised through the newspapers for Lincoln recollections in Indiana and Kentucky. Augustus Chapman, who had married Lincoln's niece Harriet, wrote to Holland in July from Charleston, Illinois, Page [End Page 13] that he had seen "in the Cincinnati Gazette of yesterdays that you are a writing the Life of Abraham Lincoln," and volunteered his collection of "facts relating to the early life of Mr. Lincoln, his Father & Mother, his sister and ancestors," which he had been assembling since "my return from the army in May last."[39] Judge L.Q. DeBruler of Spencer County, Indiana, offered to "set on foot many inquiries about Mr. L. & his family Calculated to elicit as much of his early history as possible."[40] Above all, Holland was able to trade on his own celebrity status to appeal personally to prominent Lincoln intimates like Joshua Speed and Anson Henry, to close-at-hand Washington observers of Lincoln whom Holland knew—like Massachusetts congressman George Boutwell, Supreme Court justice David Davis, John D. Defrees, and Orville Hickman Browning—and to others like George Stuart of the United States Christian Commission.

As it turned out, the further Holland climbed the ladder of public visibility, the less cooperation he was likely to get. Horace White stalled and stalled, begging as his excuse "sickness in my family & absence from the city" and finally recommending that Holland consult the chapter he had written on the Lincoln-Douglas Debates for the Scripps biography. [41] Joshua Speed confirmed that "Til 1842 no two men were ever more intimate" than he and Lincoln, an "intimacy" which "closed only with his life," but informed Holland that "It would require more time than I have to devote to it to write any thing like all that I know of him that would be of interest to his biographers." (Speed did offer to submit to a face-to-face interview, and sent Holland copies of five of Lincoln's letters to him).[42] David Davis replied that with so many would-be Lincoln biographies on foot, he "cannot give the desired assistance or discriminate in favor of any one writer," and referred Holland to Speed, Leonard Swett, and Herndon. [43] Anson Henry flatly refused to share anything with Holland until he had "the approbation & approval of the family of Mr. Lincoln." [44]

Informants who did respond to Holland found that he was scrupulous in his use of their information. He rarely softened or cen- Page [End Page 14]

If there is any single limitation on the value of the testimony of Holland's informants, it is the shallowness, both in quality and volume, of Holland's informant testimony when compared to Herndon's. Holland was not a lawyer, and did not employ Herndon's lawyerlike methods of question and examination; and working as he was to a deadline that would have his Life of Abraham Lincoln ready for publication by the end of 1865, Holland did not have the advantage either of Herndon's time or Herndon's location for gathering informant testimony. But Holland did have the great good fortune to catch a number of important informants at a critical moment in the development of the Lincoln image, before over-embroidery and the transposition of memory from other texts had begun to compromise the reliability of Lincoln informants. And since Holland's informants became the nucleus around which the far larger body of Herndon's informant testimony was to be later gathered, frequently involving the same informants, the at-times-extraordinary coincidence of story that emerges from Holland and Herndon's informants goes a substantial distance toward dispelling the dark suggestions of J.G. Randall and David Donald that Herndon forced words into the mouth of his subjects or falsified informant testimony to suit his own biographical needs. Although Herndon and Holland soon came to grief over Holland's optimistic conclusions about Lincoln's religion in general and the Newton Bateman interview in particular, Holland's informants confirm that Herndon's informants were not merely tools in Herndon's imaginative hands.

Holland's informants also tease us with the possibility that there yet remain valuable Lincoln materials, waiting to be unearthed. What became of the "many letters" of Lincoln's that Anson G. Henry claimed to possess, especially those "written just after his great contest with Douglass in 1858"? [48] (Only one letter from Lincoln to Henry survives in the Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln between 1848 and 1860, and that one, dated November 19, 1858, is one of Page [End Page 17] the most valuable comments Lincoln made on his failed race against Douglas).[49] What happened to the correspondence Joshua Speed claimed to have kept "in a spirit of sincere friendship on almost every subject til [Lincoln] became a Candidate against Douglas for the Senate"? [50] (Only one letter from Lincoln to Speed exists in the Collected Works from the period between 1849 and 1860, and that letter is one of those copied by Speed and sent to Holland, and subsequently part of the Oliver Barrett collection).

These questions, and the re-emergence of informant testimony as a key component of Lincoln biography, help to restore in some small measure the priority of Josiah Gilbert Holland as a pioneer in Lincoln biography. [51] Not only in his use of informant testimony, but also in his shrewd focus on the inner life of Abraham Lincoln, Holland stands at the head of one of the principal genres of Lincoln literature, what Mark Neely has called the "private Lincoln," as opposed to the "public Lincoln." In some senses, his Life of Abraham Lincoln can be read almost as a preliminary draft for that greater monument to the inner Lincoln, Herndon and Weik's Herndon's Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life, and for the long line of distinguished Lincoln analysis that includes Charles Strozier, William Barton, George Forgie, and Michael Burlingame. All of them find their first pattern in Holland's Life of Abraham Lincoln and some of their first testimonies in Holland's informants.

The author wishes to thank Thomas F. Schwartz, Michael Burlingame, and Paul H. Verduin for their help in locating key documents and in commenting on an earlier draft of this paper, which was read at the annual Lincoln Symposium of the Abraham Lincoln Institute of the Mid-Atlantic, Washington, D.C., March 28, 1999. Page [End Page 18] The originals of all of the following documents are in the Josiah G. Holland Papers at the New York Public Library, except for the letters of Orville Hickman Browning (no. 3) and Holland himself (no. 19), which are in the Browning Papers and the Holland File at the Chicago Historical Society.

1. William Henry Herndon to JGH

Springfield Ills May 26th 1865

My Dear Sir:

Enclosed you will please find a true Copy of Mr Lincoln's letter to me dated in 1849 when he was in Washington, he then being a member of Congress from this, the Capitol District.[52] One word of Explanation you will allow. It is this—several influential gentlemen of this City were applicants for the Receiver's Office, a branch of the Land Office. I think I took pains to write to Mr L, & urge him to appoint Mr Davis, but stated that Davis was publicly asserting that he was to get the Post Office, thus putting Mr. L wrongly on the record, he having promised an other man that Office. Subsequently he gave—had Davis appointed Receiver of the Land Office.[53] The letter is a poor one—quite—thoroughly Characteristic of the good great man now gone, yet still among us. The influential men, Lincoln's friends, are passed over and Davis Lincoln's hostile Enemy, appointed for the reasons specified in the letter. As the letter speaks for itself I send it to you. You may use your own good discreation in its Suppression or publication. It never has been made public. I have, since I saw you, received several good letters from various friends giving me information—Copies of which I shall send you soon.

When you were in my office I casually informed you that it was my intention to write & publish the subjective Mr Lincoln—"the inner life" of Mr. L. What I mean by that Expression is this—I am writing Mr. L's life—a short little thing—giving him in his passions—appetites—& affections = perceptions—memories—judgment—understanding—Will, acting under & by motives, just as he lived, breathed—ate & laughed in this world, clothed in flesh and sinew—bones & nerve. He was not God—was man: he was not perfect—had some defects & a few positive faults : he was a good man—an honest man—a living, true & noble Man—Such as the world scarcely, if Ever saw. It is my intention to write out this Life of Mr L honestly—fairly—impartially if I can, though mankind Page [End Page 19] Curse or bless me. It matters not to me. The world does not begin to understand the grand & full orb of Lincoln, as it sprang amid the heaviness of war. My purpose is to try & make it understood. This age and all future ages demand the truth. This is my purpose & motives.

I regret that you could not have been with me 8 or 10 days Consecutively. I think I could lead you to the dawn of his great light. One more word-: I shall not make my little thing of more than 50 or 75 pages, pamphlet form. I am too poor to set down & write voluminously. I have not yet the Capacity to write much at first and not that much well.

Truly your Friend

WH Herndon

2. William Henry Herndon to JGH

Springfield Ills June 8th 1865

Dear Sir:

Since I saw you last, since I wrote to you some days since, I have been searching for the facts & truths of Lincoln's life—not fictions—not fables—not floating rumors, but facts—solid facts & well attested truths. I have "been down" to Menard County where Mr L first landed and Where he first made his home in Old Sangamon. I have been with the People—ate with them—Slept with them & thought with them—cried with them too. From such an investigation—from records—from friends—old deeds & surveys etc. I am satisfied, in Connection with my own Knowledge of Mr L. for 30 years, that Mr. L's whole Early life—remains to be written. All the things we hear floating about are more or less untrue in part or as a whole.

I wish to make a Correction, & it is this—Mr Douglas promised Mr. Lincoln that if he would go home and not Speak any more in 1854 he—Douglas—would not speak more. I think, on reflection, not modifying anything Else I told you, that the understanding & obligations between them at Peoria were matured—not one-Sided.

Again—When I told you the words which Lincoln told Douglas about his impertinent criticisms—the Republicans sat down cool Page [End Page 20] & calm, satisfied that Lincoln had Douglas : they had felt uneasy at Douglas interruptions, & L position = the Democracy had seen it, but now the Republicans were happy &c—Probably this will put the point on the story—It shows the Confidence the People had in Lincoln's honor & power. [54]

Again—: Lincoln's letter to me, a copy of which I sent you, I forgot to state that I had informed him—L, that his friends here were loudly & bitterly Complaining against him for appointing Davis—a man not very popular. That is probably apparent in the letter, but if it is not it puts the point—one point to that letter.

You must allow me the privilege to bore you with Corrections. This is a sucker's privilege; and you must bear with me. We will know one an other sooner or later, and love Each other more—I mean the "Yankees" & the "suckers." We are right good "folks" out west, though that good may be hard to find by a Stranger. I can say as much [55] of the "folks" East. = I have been with them and never was more kindly or courteously treated—north or south—

My friend—you know I am no literary man, and hence you will kindly & generously look over all my faults—peculiarities &c; And what is more I defy you—I defy any man to Come and sit down in my office and write anything. My clients, my own business—Enquiries & interrogations by thousands of visitors as to Mr Lincoln—his history—acts—stories—&c—Render me simply a Tattler—a babbler. In my last letter to you you doubtless perceived a quick Conclusion—my clients demanded my Ear—pen, and time.

Enclosed you will see quite a notice of one who is utterly incompetent to fulfill the task. Such a notice gives a man a hard face in the End: it is cut from the Chicago Republican—out about 4 June.

Truly your Friend

WH Herndon

Will you have the goodness [to return] all my sayings—Lincoln's short remarks to me & to others which I gave you—Notice this—I have found some old memoranda containing the same things. When I saw you I put myself in place of Lincoln &c and thus I was fresh &c. I can now mend and better it, when I get my Expressions to you and when I put them Side by Side with my memoranda &c—I will when I fix them up—talk to friends & get Lincoln's Exact words as near as possible and then will send you true & exact Copies. Please accommodate me & I'll pay in return &c

Hurriedly

Your Friend

Page [End Page 21]

3. Orville Hickman Browning to JGH

Washington D.C. June 8, 1865

Dear Sir:

Yours of the 30th ult. addressed to me at Quincy, Illinois, has just reached me here. Since the beginning of the war I have spent the most of my time in this City; and the correspondence between the President and myself, during that period, has, consequently, been very limited. I remember, however, that at the time he revoked Fremonts' proclamation I was at my home, in Illinois, and he wrote me at considerable length in explanation and vindication of that act, giving in detail the reasons which impelled him to it[56].

The personal relations between him and myself were of a very intimate Character for thirty years, and through that period, an occasional correspondence was kept up. How many of his letters I have preserved, and how many of those not destroyed may contain any thing of public interest I cannot now say, as they are all at Quincy, Illinois.

I hope to reach home in July, and will there endeavor to examine them, and write you further upon the subject.

Very Respectfully yours

O.H. Browning

4. Erastus Wright to JGH

Springfield Illinois 10th June / 65

Dr. Holland

I have recently seen Mr. Dennis F. Hanks and have through him obtained the History of the Ancestry of Abraham Lincoln, going back to his Grandfather Mordecai Lincoln and his Grand Mothers Lucy Sparrow, and His Father Thomas Lincoln and his Mother Nancy Lincoln, whose maiden Name was Nancy Sparrow.

I have obtained through Said D.F. Hanks a great many incidents and facts that you will be glad, Yes Doubly Glad to get if you intend giving My old Neighbor Abraham's History. I got home last night and you may expect Soon to receive the genealogy as far as Page [End Page 22] any one in this Country Can give. Wm. H. Herndon former partner of A. Lincoln Is my Neighbor and will doubtless do all he can to assist you. You will remember I called on you at the St. Nicholas Hotel, went with you to the Office of Mr. N. Bateman State Superintendent [of] Public Schools and I had to take the Case that day and had not the pleasure of taking tea with you at our house with My Son-in-law, R.P. Johnston & Lady and the Episcopal Clergyman Mr. W.F.B. Jackson.

I enclose my Photograph that you may remember me when I cast up in Springfield Mass.

Mrs. Trophima Wright a widow living in Chicopee Mass and her Daughter Leonora living with her. Oscar A. Wright her Son A machinist is Married and was Sup. of about 100 hands in the Springfield Armory last year, 1864. His Mother Trophima is my own Cousin by My Father's Side. It may be in your way to Call on her some time.

Yours in considerable haste

Erastus Wright

5. George S. Boutwell to JGH

Boston June 10, 1865

My dear Sir,

I can give you Mr. Lincoln's remarks in reference to the meeting of governors at Altoona substantially as they were made. Having determined in October 1862, to visit Massachusetts and take part in the canvass I called upon the President the day preceding my departure. In connection with some remarks upon affairs at home I mentioned that one Judge Parker had appeared as an active leader of the "Peoples Party," and in a public speech had asserted that the President was frightened by the meeting of the Governors at Altoona, and thus led to issue the Proclamation of Emancipation.[57] "Now," said the President, dropping down into his chair as though he intended to be at ease, "I can tell you just how that was. When Lee came over the river I made a resolve that when McClellan drove him back—and I expected he would do it sometime or other—I would send the Proclamation after him. I worked upon it and got it pretty much prepared. The battle of Antietam was fought on Wednesday, but I could not find out till Saturday whether we had really won a victory or not. It was then too late to issue the Proclamation that week, and I dressed it over a little on Sunday, and Page [End Page 23] on Monday I gave it to them. The fact is I never thought of the meeting of the governors at Altoona and I can hardly remember that I knew anything about it."[58]

You have the substance and nearly the language of his remarks. When I reached Massachusetts I could not ascertain that Judge Parker's declaration was regarded as of any importance and hence I never referred to the subject in public. In the debate with Mallory I had the conversation in mind although I did not refer to it.[59]

I hope you will get access to Mr. Lincoln's letters to officers in the field and in command at important points. I think they show his power,—at least those that I know something about impressed me very much.

Yrs. truly

Geo. S. Boutwell

6. Anson G. Henry to JGH

Washington June 16th 1865

Dear Sir

Your letter of June 12th is just received.

It is true that I was an old and very intimate friend of President Lincoln, and so recognized by him up to the day of his death. It is also true that I have many letters of his, most of which however are of a purely private character. Those of a political character would no doubt be of interest to the public. One in particular, written just after his great contest with Douglass in 1858 - Page [End Page 24]

Those of a private & Confidential character would not be needed to illustrate his character and habits in early life, they being now well understood. Consequently their publication would only gratify a morbid curiosity.

My acquaintance with Mr. Lincoln began in 1834 in Springfield Ills. and I was in almost daily intercourse with him from that time up to 1852, when I emigrated to Oregon. I did not See him again untill Feby. 1863, when I spent several weeks at the White House as his guest. I saw much of him again this past winter & Spring.

All of my papers and correspondence are now with my family on the Pacific. Should I remain here, (a matter not yet settled) they will be here with my family in Nov. or Dec. next. [60]

I shall be glad to furnish you Every aid in my power, provided your undertaking meets the approbation & approval of the family of Mr. Lincoln, for what I may be able to contribute towards a reliable and interesting Biography of my lamented friend, must to a reasonable Extent be made to enure to the pecuniary benefit of his family, who have by no means been left in as independent Circumstances as has been represented by those who would gladly see Mrs. Lincoln reduced to the humiliating necessity of boarding at a Second class Hotel the remainder of her life.

I will write Robert T. Lincoln by the next mail on the Subject.

Very Truly

Your Obdt. Srvt.

Anson G. Henry

7a. Newton Bateman to JGH

Office Supt. Public Instruction, Illinois

Springfield June 19 1865

J.G. Holland M.D.

Springfield, Mass.

Dear Sir:

I hope the Enclosed notes are not too late for your purpose. I have had to write them in the office subject to constant interruption—and I am conscious that several points have at this moment escaped me which in a more quiet hour I could recall. But I am not likely Page [End Page 25] to know a more favorable time, & I will send them as they are—hoping that they will help to elucidate one phase at least in the character of Mr Lincoln—If there is anything further that I can do to aid you in getting materials, please let me Know -

With best wishes,

Very truly yours

Newton Bateman

7b.

Mr. Lincoln was first nominated for the Presidency, at Chicago, May 1860. He immediately occupied the Executive Chamber in the State House, as a Reception Room, where he could see & consult with his friends. I was then State Supt of Pub. Inst. & my office was adjoining the room occupied by Mr Lincoln, with a door opening from one to the other, which was frequently open so that I could not help hearing much of the conversation between Mr L & his friends & visitors. I saw him almost hourly during the seven months & more that he remained in the State House, & quite frequently he called to me to come into his room on various occasions & for various purposes.

A careful canvass had been made of this city (Springfield) and the book, showing the candidate for whom Each citizen intended to vote, had been placed in Mr Lincolns hands. Late in the afternoon, towards the close of October 1860, after all had left his room, Mr Lincoln locked the door & requested me to lock mine & come to him. He placed a chair for me close by his side. He had been Examining the afore-named book, which he still held in his hand. "Let us look over this book," said he, Explaining its character. "I wish particularly to see how the ministers of Springfield are going to vote."

We turned the leaves one by one, each holding it be a hand, he asking me, now & then, if this one & that one were not a minister, or an elder, or member of such & such a church in the city, and sadly expressing his surprise upon receiving an affirmative answer. in this manner we went through the book, which he then closed & sat for some moments, with his eye upon a pencil memorandum which he had made, in profound silence.

At length, turning to me, with a look the saddest I had ever seen, I cannot tell how touchingly sad it was, he said: "Mr B. here are 23 ministers of different denominations, and all of them are against me but 3 & here are a great many prominent members of the Page [End Page 26] churches here, a very large majority of whom are against me. Mr B. I am not a Christian, God knows I would be one, but I have carefully read the Bible & I do not so understand this book" (drawing from his bosom a pocket testament). "These men will know that I am for freedom in the territories—freedom everywhere as far as the constitution & laws will permit, and that my opponents are for slavery. They know this, & yet with this book in their hands, in the light of which human bondage cannot live a moment, they are going to vote against me. I do not understand it at all."

Here Mr Lincoln paused a good while—then arose & walked back & forth several times, when he sat down & presently said, with deep emotion & many tears, "I know there is a God & that he hates [61] injustice & slavery. I see the storm coming & I know that His hand is in it. If he has a place & work for me, and I think He has, I believe I am ready. I am nothing, but truth is Everything. I know I am right because I know that liberty is right, for Christ teaches it and Christ is God. I have told them that a house divided against itself cannot stand, & Christ & reason say the same, & they will find it so. Douglas dont care whether slavery is voted up or voted down, but God cares & humanity cares, & I care, and with His help I shall not fail. I may not see the End, but it will come, and I shall be vindicated, and these men will find that they have not read their Bibles aright." Much of this was uttered as if speaking to himself, & with a sad solemnity of manner that I cannot describe. He resumed: "Dont it appear strange that christian men can ignore the moral aspects of this contest? A revelation could not make it plainer to me that slavery or the government must be destroyed. The future would be something awful, as I look at it, but for this rock on which I stand, (meaning the bible, which he held in his hand), Especially with the knowledge of how these ministers are going to vote. It seems as if God had borne with this thing (meaning slavery) until the very teachers of religion have come to defend it from the Bible & claim for it a divine character & sanction, and now the cup of iniquity is full, & the vials of wrath will be poured out." He here referred to the attitude of some prominent clergymen in the South, Ross & Palmer [62] among the number, & spoke of the atrociousness & blasphemy of their attempts to defend American Slavery on Bible grounds.

Mr Lincoln's language made a vivid impression upon me, & while I do not claim that the above quotations are absolutely verbatim, I know that they are very nearly so, and the sentiments are Exactly as he uttered them. Page [End Page 27]

The conversation was continued a long time, & all that he said was of a peculiarly deep & tender religious tone, tinged with a profound & touching melancholy. He repeatedly referred to his conviction that the day of wrath was at hand, & that he was to be an actor in the terrible drama, wh would issue in the overthrow of Slavery, tho he might not live to see it.

He repeated many passages of the Bible, in a very reverent & devout way, & seemed especially impressed with the solemn grandeur of portions of Revelation describing the wrath of Almighty God. In the course of the conversation he dwelt much upon the necessity of faith, faith in God, the christian's God, as an element of successful statesmanship, especially in times like these; said it gave that calmness & tranquility of mind, that assurance of ultimate success, which made one firm & immoveable amid the wildest excitements &c. He said he believed in divine providence & recognized God in History. He also[63] stated his belief in the duty, privilege, & efficacy of prayer, & intimated in unmistakeable terms that he had sought, in that way, the divine guidance & favor. The effect of the interview was to fix in my mind the conviction that Mr Lincoln had, in his quiet way, worked his way up to the christian stand-point; that he had found God; & was anchored upon his truth—a conviction that nothing could Ever shake for a moment. I have heard that he afterwards claimed to be & resolved to live the life of a christian—I do not know if this was so, but I am firmly persuaded that at the time I speak of he was not far from the kingdom—nearer then he himself seemed to think.

I remarked, as we were about to separate, that I had not supposed that he was accustomed to think so much upon that class of subjects, & that his friends generally were ignorant of the sentiments which he had Expressed to me. He replied quietly: "I know they are. I am obliged to appear different to them, but I think more on these subjects than all others, & have done so for years, & I am willing that you should know it."[64]

Mr Lincoln was ambitious, but his aims were so lofty & good, & the means he would use so pure & noble, that it was not the ambition of other men. There was something almost Christlike in his aspirations, for I believe he sought place & power that he might use them to bless the race & not to aggrandize himself—I believe further that he was never Even seriously tempted to resort to dishonorable means to gain his Ends.

Thus subordinated he not only desired preferment, but keenly enjoyed success. But at the time I believe it was entirely true of him Page [End Page 28] that he "would rather be right than be President."

Dear noble heroic Lincoln—God sends us but one such man in a century, & when their work is done how quickly He translates them.

8. Joshua F. Speed to JGH

Louisville 22 June 1865

Dear Sir—

I have delayed answering yours of the 12th for want of time to attend it -

I have had Copies of five letters, Commencing dates in 1841, and running to 1855, which Copies I enclose.[65]

Some of them are on business—but they go to show the accuracy & promptitude with which he always [attended] to interests entrusted to him.

The letter about the trial of the Trailors for the supposed murder of Fisher—which is reported in the law Books—I have never seen so well done as in this letter.

The letter of Aug 24, 1855 is an able one—and if we look at subsequent events, has now all the marks of prophecy—You must judge of them for yourself -

My acquaintance with Mr. Lincoln commenced in 1834—Til 1842 no two men were ever more intimate -

After that time I moved to Ky [66] Though we Continued to Correspond in a spirit of sincere friendship on almost every subject til he became a Candidate against Douglas for the Senate—Our friendship and intimacy closed only with his life -

It would require more time than I have to devote to it to write any thing like all that I know of him that would be of interest to his biographers -

If I could see you I have no doubt that I could give you many facts in Connection with his early life which would be of great value.

Your friend

J.F. Speed

Page [End Page 29]

9. Albert Hale to JGH

Springfield 22 June 1865

Dear Sir

I visited Mr. Brown with whom Mr. Lincoln boarded. I worked on the same farm in the year 1827. Mr. Brown came to this County in Octo 1826—39 years ago. Mr. Brown rented a portion of the farm on which he now lives, & Mr. Lincoln was employed on the same farm by the owner, a Mr. Taylor, and boarded with Mr. Brown. This varies the story a little from that which I recd. from Mrs. Brown on the 6th May 1861.- tho: it leaves the fact of his working as a hired man on the farm, working & boarding with Mr. Brown all as stated to me. Mrs. Brown is dead & while Mr. B. at the time of my visit to him was in doubt as to the year when Mr. L. worked on the farm yet according to his promise he has sent me what he now feels since is the true date, 1827—The Crop was hauled to Galena with ox-teams, about 250 miles over an almost pathless region, inhabited in part by the Savages, when a bridge was the next thing to a miracle. Mr. Lincoln went with the caravan & as I suppose drove one of the teams. In conversation with those who were very early settlers in this city I find them quite disposed to doubt the accuracy of Brown as to the date, 1827—They think the date too early. [67] Mr. Herndon, whom I think you saw in your recent visit to this city—who is preparing a Biography of Mr. Lincoln—informs me that he has found it very difficult to trace him along this period & I intend to recommend him to inquire out the Mr. Taylor who was the owner of the farm—who is probably dead, but of whom there may be records, accounts &c. left in the hands of those who as children, relations, or neighbors stood in business relations to him. Or if dead, the Probate Court will contain, in its files & records, the means of correcting Mr. Brown, if he is mistaken. If any new light is gained, you may expect to get it from me.

The story you desired me to write out is as follows: I was visiting a Scotch Lady, a member of my church who was near her end with Consumption. It was in May, 1861, & in the neighborhood of Page [End Page 30] the farm & residence of Mr. Brown about 7 miles north of this city. Two old Ladies of the neighborhood had come in to spend the day & do what they might for [the] sick lady. While we were sitting there some one mentioned the name of Mr. Lincoln: when one of these ladies, Mrs. Brown—said, "Well, I remember Mr. Linkin, he worked with my old man 34 years ago & made a crop (34 years in 1861—39 now). Where did you live then? I asked. We lived on the same farm where we live now—& he worked all the season & made a crop of corn & then the next winter ('27, '28) they hauled the corn all the way to Galena & sold it for $2.50 per bushell—There was no market for corn here then (if sold at all 6 cents per bushell was as much as cd. be realized). At that time said the old lady there was no public houses in the country & travellers were obliged to stay at any house near the road that could take them in. And one evening a right smart looking man rode up to the fence & asked my old man if he cd. get to stay over night? Well, said Mr. Brown, we can feed your Crittur & give you something to eat but we can't lodge you unless you can sleep in the same bed with my hired man. The man hesitated— & asked, where is he? Well said Mr. Brown, you can come & see him. So the man got down from his Crittur & Mr. Brown took him around where in the shade of the house Mr. Lincoln lay stretched at full length (6 feet 4 inches) on the green grass with an open book before him. Pointing to him, "there", said Mr. Brown "he is." The stranger gazed on him a moment & said, well "I think he'll do" & stayed, sleeping on the same bed with Mr. L. the future president of the U. States. [68]

It was a few miles only from the farm on the Sangamon River, where Mr. Lincoln built a flat Boat & went with it, loaded with corn & down the stream to the Illinois river at Beardstown, thence down the Illinois river to the Misipippi & so on to New Orleans.

If any new light on the subject of the Lincoln chronology comes to me, I will send it forward.

We are all well as usual.

Very truly Yours

A. Hale

Page [End Page 31]

10. Lucius Quintus DeBruler to JGH

Rockport Ind. June 28. 1865

Hon. J.G. Holland,

Dear Sir:-

Your favor of the 12th inst asking me to give you such material as I could find here for the purpose of assisting you in writing the life of our late President is at hand. Mr. Lincoln, as you Know, Spent Some years of his boyhood in this, Spencer County, but that was long ago, long, indeed, before I lived here myself. The most of his old neighbors are dead and all that is Known of Mr Lincoln in this County is rappidly going into tradition. I have Set on foot many inquiries about Mr. L & his family Calculated to elicit as much of his early history as possible and I have placed the material in the care of an active & intelligent young man, [69] and as soon as possible I will give you the result and if you find it worth any thing you can use it.

Respectfully

L.Q. DeBruler

11a. Erastus Wright to JGH

Springfield Illinois 3d July 1865

Dear Sir

From my short personal acquaintance with you and your kind letter of 18 June/65 I have taken Some pains to get as Many facts and incidents of the Early History of Abraham Lincoln as I could as it was rather obscure.

It may be regarded as too prolix Yet most of these embody facts that will be very interesting and instructive to other generations. You Can concentrate and put it "Ship Shape" as my time would not allow even if I were competent =

Mr. Wm. H. Herndon sends his regards and good wishes and would aid you if you desire but he is very busy in getting up a history of Lincoln especially the early part of his life.

If any thing more [unintelligible] you will command my services Page [End Page 32] and it will be Soon forth Coming. I went up to Chicago twice [unintelligible] partly to get more fully Lincolns Biography and found his Cousins Dennis F. Hanks and John Hanks rather dull in his History.

Hoping for your Great Success

I am your obt Sevt

Erastus Wright

11b.

Biographical Sketches of Abraham Lincoln[70] as taken of his two cousins Dennis F. hanks and John Hanks while at Chicago Ills while attending the Sanitary Fair in June 1865. Taken down in writing by Erastus Wright of Springfield Illinois who was among the first Settlers in the "Sangamon Country" Now sixty Six years old and a resident of Springfield about 43 years and seen it grow from its first house a personal friend and intimately acquainted with Abraham Lincoln since he came into the country in 1831, a poor farmer boy. (Viz The History to the first year after Lincoln came into the country and until 1832 by acquaintances and my personal recollections as I often Saw him.)

Mr. Dennis F. Hanks states that Abraham Lincoln was the Son of Thomas Lincoln who was the Son of Mordecai Lincoln of Old Virginia.[71]

Mordecai the Grandfather of Abraham was killed by the Indians near Boone Station in Kentucky when his son Thomas was only six years old. His Grand Father Mordecai was Married in Old Virginia to a woman whose name was Lucy Hanks [72] (and She was my own Aunt) they were both born in Virginia and they lived on the Roanoke River, the County and identical place I cannot State.

They afterward moved into Kentucky about the year 1790 and She died in Mercer County, Ky.

Thomas Lincoln the Father of Abraham was born in Virginia on the Roanoke river. His religious belief coincided with the Free Will Baptists to which church he was connected and so continued through life. [73]

was married in Hardin County Kentucky to a lady whose maiden name was Nancy Sparrow. She lived near Elizabethtown married near 1806. This Thomas and Nancy were the Parents of Abraham Lincoln. They had three children Sally Thomas and Abraham.

After they Moved from Kentucky to Spencer County Indiana where they lived [left blank] years Sally Married to one Aaron Page [End Page 33] Grigsby of that place and died in about twelve months at childbirth. Thomas the second child was to bear his Fathers name but did not live three days. Abraham the other and only child was all that was there left to transmit the name.

They lived in Spencer County Indiana Several years and in Sept 1818 his Mother Lucy Lincoln died. She was a plain amiable quiet retiring woman Sympathising genial and affectionate in all her walks and might truly be Said, one of the best of women—

She was born in Mercer County Kentucky I think in the year 1792.

Thomas Lincoln the Father of Abraham was a Farmer by profession and was also a Carpenter and Cabinetmaker he learnt his trade as a Carpenter in Hardin Co Ky with Joseph Hanks who was my uncle and he married said Joseph Hanks Niece who was my own Cousin. he worked as a Mechanic occasionally but his main business was farming.

Said Thomas Lincoln the father of Abraham was a Pioneer in Kentucky and also in Indiana and Illinois and like most Pioneers delighted in having a "good hunt"

The Deer, the Turkey, the Bear the Wolf the Wildcat and occasionally a big Panther afforded him no small amount of pleasure and amusement, and also much means of subsistence. Deer and Turkey there were abundant.

Bees and wild honey abounded in the timber and groves, and all the Early Settlers made great account of those for subsistence.

Thomas Lincoln was a large Man and of Great Muscular power. His usual weight was 196 pounds for I have weighed him many a time; he was five feet ten and a half inches high and well proportioned. He was Singular in one point, though not a very fleshy man he was built so compact that it was difficult to find or feel a rib in his body, muscular and powerful his equal I never Saw.

At a gathering in Hardinsburg Kentucky One Mr. Breckinridge was reputed to be the best man in Breckinridge County and Could whip any man in it.

Lincoln's friends and neighbors disputed it, and said Thomas Lincoln could whip him at a fair fight. They soon stript and went at it. and Lincoln whipt him in less than two minutes without getting a Scratch; much to the Mortification of the Breckinridge men.

Abraham Lincoln was born in Hardin County Kentucky on 12th Feby 1809 On Knob Creek So Called which ran into the Rolling Fork which emptied into the Beach Fork and then into the Ohio River he was sent to School with his Sister Sally in Kentucky some Page [End Page 34] 4 or 5 weeks but was too young to profit much After moving from Kentucky into Indiana his Father went to farming and he went to School again about 6 months while in Indiana: after living in Indiana about 13 years his Father moved to Macon County Illinois on 20 March 1830 and pitched his tent and built a cabin about two miles North West of Decatur the Present County Seat of Macon County Ills Abraham was now twenty one years old and helped build the same Cabin lately exhibited at the great Sanitary Fair at Chicago Ills

His Father Thomas Lincoln like Most Pioneers lived in log houses a large portion of his life. The first house shelter in Indiana was a half faced Camp such as is often now seen in Sugar Camps. Their tables were a broad Puncheon hewn out from the Slab of a large log Split with mawl and wedges, and dressed off and then augur holes put in to receive the legs This was then no uncommon thing with all the new Settlers; Yea: I made one myself for Abraham Lincoln's father when we were settled near together in Indiana After Abraham's mother died in Sept 1818 in Indiana, Thomas Lincoln went to Kentucky and Married a widow Lady One Mrs. Sarah Johnston a Daughter of Christopher Bush in Elizabethtown Hardin County Ky. He had no children by the second women. She is supposed to be Still living in Coles County Illinois near Charleston Abraham Lincoln got the name of "Rail Splitter" while working with his Father and the said Dennis F Hanks and John Hanks who lived near by in the county of Macon Ills soon after they came from Indiana to Illinois Abraham was strong and muscular and could wield the Axe and Mawl with the best of them.

John hanks aged 63 years a cousin of Dennis Hanks while at Chicago in June 1865 confirmed the Statements preceding, made by his Cousin Dennis F Hanks, and gives to the writer Erastus Wright this further information Viz That He and Abraham Lincoln then living near Decatur Macon Co Ills a man by the name of David Offitt[74] wanted to get a Flat Boat built and hired Him Said John Hanks and Abraham Lincoln to build one for him Eighteen feet wide and Eighty feet long, which they did at $18 per Month, and Said Offitt filled it with bulk Pork, Barreled Pork live hogs and corn in the ear: Said Offitt then hired them with others to go with it down to New Orleans. They built the Boat about 7 miles NW of Springfield the present capital of Illinois and went with it down the Sangamon River into the Illinois River then down the Illinois to the Mississippi River, then down the Mississippi to New Orleans. This was in the year of 1831 which used up Most of the first year Page [End Page 35] that Abraham acted for himself building the boat and going down to New Orleans La this the first chapter of his eventful life.

After returning from New Orleans he went to a little village of 15 or 20 houses called New Salem Situated on the Sangamon River about 25 Miles NW of Springfield and attended Store for one Mr. S. Hill and Studied Surveying and was soon appointed Deputy Surveyor for that part of the Sangamon Country which there united some 4 or 5 of the now existing Counties in 1832 A Lincoln volunteered as a Private under Capt Elijah Iles to go and suppress the invasions by the Indians on the new settlements in the North part of the State, Iles was Commissioned by Gov. John Reynolds as Commander in Chief. Dated 28 May 1832. J.T. Stewart now member of Congress was also a Private in the Same Company with Lincoln. Dr. J.M. Early James D. Henry afterwards Genl. Henry all went as Privates. They were absent about three Months under command of Brigadier General Atkinson in what is known in History as the Black Hawk War. The Regt was inspected by a young man by name of Robert Anderson Asst Inspector General

Lincoln spent 3 or 4 years at New Salem and [unintelligible] his time in tending Store and Surveying.

In 1836 Sangamon County which embraced a large tract of Country was under the Law then entitled to 9 Members in the Legislature. The Democrats brought out a full ticket of 9 and the Whigs 9 more and they published their times of Speaking in the various settlements and they agreed to all go together and Speak alternately which they did the Eighteen Canvassed the extended Country giving their view of County and State interests and National Policy. At the Election in August the Whig ticket prevailed and the first of Decr 1836 they took their Seats in the Legislature at Vandalia Ills. In the Senate Job Fletcher and Archer G Herndon In the House Abraham Lincoln, Andrew McCormick Edward D. Baker, William F. Elkin. John Dawson, Ninian W. Edwards and R.L Wilson These Nine were all of good size and mostly tall men and they soon got the name of "The Long Nine" Through their exertions the Capitol of the State was to be removed to Springfield after a certain period. In the Spring of 1837 Mr. Lincoln came to Settle in Springfield and was offered a place in J T Stewarts Law Office which he accepted and made rapid proficiency in Law and Soon became a Strong antagonist with any Member of the Bar. His antagonists always giving him the Credit of being fair and honourable. Page [End Page 36]

12. John V. Farwell to JGH

Chicago, July 6th, 1865

Dear Sir

I have yours of the 3rd inst. Soon after Mr. Lincoln's -election he made a visit to our city & while here I called on him & requested the honor of a visit & a little speech to my Mission Sunday School: which was made up of neglected poor children & held in the "North Market Hall," & was called by that name.

After explaining the nature of the school to him, he said, "I will go, if you will not call on me to Speak"- I answered that I would not ask him to Speak: but he could use his discretion as to the propriety of doing so, after seeing the school. He was at dinner with a large circle of his friends when the carriage called for him, & he excused himself immediately to fill his engagement[75].

he appeared to enjoy the scene exceedingly, while several boys were pointed out to him, who had been reformed from lives of crime & debauchery, & upon taking leave of the school, volunteered a few well chosen remarks, calculated to encourage them all to strive for high positions in society. As much as I can recollect his words, they were as follows,

"My little friends, I am glad to see you in such a place as this, surrounded by men & women who seem to be intent upon nothing but doing you good. While I have never made a profession of religion, I do not hesitate a moment in recommending you to follow the advice of these teachers, and to say to you [76] that the poorest boy among you may aspire to the highest positions in the gift of the people if capacity & energy are linked with honesty in the development of [77] character.

I was once a poor boy myself, with perhaps less to encourage me than very many that I see here to day & therefore I could not leave you, without saying a word to inspire your hopes, & sharpen your energies into seeking to make yourselves useful & honored."

When the war broke out over seventy members of the school Page [End Page 37] enlisted and I have no doubt that very many of them did so as the result of Mr. Lincoln's short address to them on this occasion.

This incident serves to illustrate his interest in the common people—As a member of the Christian Comm. and an elector for this district I have had some opportunities of studying his character & perhaps it may be summed up in these few words—the desire & the determination to do right.

Yours very truly

John V. Farwell

13. Erastus Wright to JGH

Springfield Ills 10th July 1865

Dear Sir

I wrote you on 3rd July some 11 pages and last week I was in the vicinity where A. Lincoln Spent most of the first Six years after he Struck out for himself and Saw two men with whom he boarded during those 6 years. Viz. James Short aged 60 years States he lived at New Salem, Illinois, in 1831, was acquainted with Lincoln all the time he lived there about 6 years. When Lincoln returned from N. Orleans Mr. Offitt who hired him to go to N.O. Again hired him[78] as his Clerk to buy wheat which he did and had it Manufactured at New Salem Mills on the Sangamon River owned and run by John Cameron & James Rutledge. Lincoln boarded with said Rutledge and was partial towards his daughter Miss Ann an amiable young Lady who took Sick and died causing him much sorrow and unhappiness.

He in company with one Wm. Berry bought Goods & groceries and went into trade and in about a year burst up and their effects were Sold, Peter van Bergen of Springfield Ills was the Officer who Sold them out, and Said James Short bought Lincoln's Compass and Surveying apparatus and afterwards to show his good will made Mr. Lincoln a present of these. He, Lincoln, was appointed Deputy Surveyor for all that part of the County (under John Calhoun of Kansas notoriety). He volunteered in 1832 to go to the Black Hawk War, was Elected by his comrades as their Captain. Page [End Page 38] E.D. Baker (Latterly Slain at Balls Bluffs as Genl Baker) was their major. Said Mr. Short Sold Baker a Horse, Said Baker's having died at Beardstown, Cass Co Ills. Lincoln Studied Surveying, went out and surveyed land where needed which, at that day, was but little barely enough to pay his board. he Spent most of his leisure time from 1832 to 1836 in Studying Law by himself. he Studied English Grammar some and went to recite his lessons to one Mentor Graham, Esq. then a School teacher at that place and now a resident of Petersburg the County seat (or County town) of Menard County. Mr. Short states that Mr. Lincoln boarded with him Sometime during those 6 years, was found of pitching quates, telling Stories, and all proper amusements, cheerful, and full of Highlarity and fun which made him Companionable and rather conspicuous among his associates.

I also called upon Henry Onstott now living at Havanna, Mason County Ills who stated that in 1830 he lived at New Salem, Menard Co Ills. and was personally acquainted with Abraham Lincoln after he came there in 1831 until he moved to Springfield Ill. That the first time he Saw Lincoln was when he came down the Sangamon River in a flat Boat and Stopt at New Salem, near the last of May 1831. When he jumped off the boat bareheaded, and barefooted with a coarse homespun Shirt the Sleeves rolled up to his elbows and coarse homespun Pants (Jeanes or Linsey Woolsey) and these rolled up nearly to his Knees; often combing his dark bushy hair with his fingers and being rather lank and tall made a rather Singular grotesque appearance.

On Lincolns return from N Orleans Mr. Offitt who had the boat built, hired Lincoln again to buy wheat at New Salem and he had it ground up at Cameron & Rutledge Mill called the New Salem Mills. His Surveying and Studying Law during 4 or 5 years agreeing with the report of Jas. Short afore mentioned. That Lincoln also Boarded with his family Several months that He (Onstott) boarded him and lodged him for two dollars per week. That Lincoln like other young men at that early day found it hard work to meet expenses. It was hard times there for all the Pioneers and new settlements, even for those who had property to pay their way and Keep from going down stream.

Lincoln though poor in worldly goods was rich in a fertile imagination, loved to be odd, tell Stories, and make the boys laugh, a man of temperate habits, truthful and honest, never addicted to profane language to the use of Spirituous liquors, nor Tobacco, and had the good will of all that Knew him. Page [End Page 39]

He was a Candidate for the Legislature in 1832 and Carried (in his own precinct) all the Whig and Democratic votes—but the Country was large and he was not known in other parts of the County and failed to be Elected. After he was Elected and went to the Legislature in the year 1836 he removed to Springfield and Practiced Law Successfully Married a Miss Mary Todd from Kentucky and raised a family of children. thereafter Lincolns History is Public and I trust imperishably recorded in Heaven as well as in the hearts of the American People.

14. Erastus Wright to JGH

Springfield Ills 10 July 1865

Dr. J.G. Holland

Having lived here about 43 years, ten years before Mr. Lincoln came to the Country, I had knowledge of most that transpired in his day and knew all the early Setlers having, Seen Springfield grow from the first house, now past 66 years, born in 1799 in Bernardiston, Mass.

I will mention an incident in confirmation, for your history of facts.

After Mr. Lincoln was Elected as President of the U States while in his reception room recounting the varied scenes and Changes of life Mr. Lincoln remarked in these words

"Mr. Wright The first time I ever saw you was when I was working on the boat at Sangamon Town and you were assessing the County" which fact I well recollected and it convinced me of his Clear head and Strong retentive Memory.

I have put myself out to gather al the incidents of Lincolns early life, you can cull out, and abridge, but all Illinoisans yea the Country will like to hear the most of it. You can arrange the facts and dress them up "Ship Shape"

Yours Truly

Erastus Wright

15. George H. Stuart to JGH

Philadelphia 13 July 1865

My Dear Sir,

I regret exceedingly that my never-ending business of all kinds and characters has prevented my earlier replying to your note of Page [End Page 40] 21 May and to a later one which I have mislaid. I am afraid it is now too late but trust that you may be able to find something available for your purpose in this.