Lincoln's Economics and the American Dream: A Reappraisal

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Good monographs in history rely, implicitly or explicitly, on a larger master narrative to make sense of the events they describe and to give those events some meaning in a larger historical vision. Thus according to Gabor S. Borritt, the leading historian of Lincoln's economic thought, "Lincoln was possessed by the optimism of Western Civilization, reborn in the Renaissance, grown to maturity in the Enlightenment, and triumphant in nineteenth century America, which saw man as the master of his own destiny." [1]

The intense materialism that underlined [Lincoln's] peace plan was typical of mid-nineteenth century Western civilization. Its optimistic variant was American, and it was not only shared but carried beyond ordinary limits by Lincoln. This, perhaps more than any other of his qualities, justified James Russell Lowell's evaluation of the President as "the first American." He was ahead of his times. He saw the reach of material prowess as potentially unbounded. It could even play a giant role in bringing peace to a war of brothers.

Surely, Lincoln was also a highly moral, indeed spiritual, being. Yet this characteristic was thoroughly intermingled with his materialism and while cleansing it, also strengthened it. This materialism carried his America along an often glorious and beneficial road into the twentieth century. [2]

But in order to make American history of one, ever-more-Jeffersonian, piece, historians have downplayed the Romantic period, interpreting it in light of what came after rather than accepting it on its own terms. While scholars of American literature obviously dwell more lovingly on the era, it is easier for historians to skip along from Jefferson's Declaration and Franklin's kite to Kennedy's inaugural and the Apollo moonshot, if they can avoid getting too bogged down in the muddy intellectual terrain of Melville, Hawthorne, Poe, and Lincoln. But at least two of the most important figures in mid-nineteenth-century American life, George Bancroft and (as Boritt here hints) Abraham Lincoln, did not write history in quite this way; neither would have claimed that "endless material progress [was] the heritage of Western Civilization" without stressing the non-material aspirations they considered more important.[4] Many writers of this period used the term "Christian Civilization" either to describe a reality or to characterize an ideal, and with that they sought not just to "cleanse" materialism and utilitarianism, but to redeem it. After the war, a Twain or a Holmes Jr. would see mostly hypocrisy in this pre-war Romanticism. But however deserving of derision, it pays to remember just what the pretensions were that the post-war cynics skewered in their now-familiar works. Page [End Page 52]

Whether or not they were deluding themselves, Americans of the pre-war period almost universally sought to make material advancement a means to something still higher. "This religious impulse fused in the minds of many Whigs with their desire for economic development to create a vision of national progress that would be both moral and material." [5] For the most influential historian of the day, materialism belonged to the Enlightenment (and an emasculated Europe), and though doubtless a necessary stage in the progress of mankind, this Enlightenment materialism was to be overcome as part of the providential scheme. In Bancroft's words, "the senseless strife between rationalism and supernaturalism will come to an end; an age of skepticism will not again be called an age of reason; and reason and religion will be found in accord." [6] Where Bancroft projected his own democratic idealism onto the Enlightenment world of Jefferson, and even onto the Puritans, we in turn have projected our own democratic materialism into the world of Bancroft and Lincoln. Thus, ironically, our teleological histories turn George Bancroft precisely on his head. We simply replace his Romantic idealist assumptions with modernist materialistic assumptions of our own. For however strongly Lincoln promoted material advancement, as a Romantic intellectual there were matters for him of much greater importance.

In Lincoln and the Economics of the American Dream, Gabor S. Boritt reconstructed Lincoln's Whig economic vision and pointed out that economic opportunity was one of the unifying themes of Lincoln's public career from his first campaigns for a place in the Illinois legislature through to his death. For Lincoln, government had a moral obligation to provide economic opportunity for the people, especially the poor. Accordingly, he stood for positive government intervention in the economy in the form of a national bank and various public works projects. In articulating this thesis, Boritt used "the American dream," or simply "the dream," as shorthand for a cluster of primarily economic values that recurred in the sayings and doings of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln himself never used such terms, but that in itself is no critique. Boritt's economic "dream" was a powerful heuristic device. While Boritt pushed the interpretive limits of his thesis, he openly acknowledged the points where Page [End Page 53] it seemed unable to account fully for Lincoln's words and actions. Even as Boritt pressed forward with his portrait of a very economics-minded Lincoln, he acknowledged that in Lincoln's speeches, economics always remained subordinate to a moral vision. "Lincoln," he said, "found pure raw materialism unpalatable—however much he relied on it in his attempts to lead men. Life had to have deeper meaning."[7] If Lincoln did not organize his own thoughts around "the American Dream," it may be of some interest to know what cluster of words he did use. An examination of Boritt's thesis provides a good way to appraise the significance of Lincoln's religious language, language he used to put his economic as well as his political and moral thought into a larger perspective.

In emphasizing the economic aspects of Lincoln's thought, Boritt built in part on the work of Eric Foner, who emphasized the economic vision of the Republican party in the 1850s and placed "at the center of the Republican ideology ... the notion of 'free labor.'" Like Boritt, Foner acknowledged an important moral element in the antislavery crusade of the Republican party in the 1850s; and he noted that Republican leaders "did develop a policy which recognized the essential humanity of the Negro." But because of the undeniably racist views so prevalent in Northern society, and because of the consequent lack of sympathy for the crusade of the abolitionists and the plight of the slaves themselves, Foner emphasized the ways Republicans also appealed to the self-interest of voters with a free-soil ideology; and Boritt's "dream" corresponded closely with Foner's "ideology." Foner also stressed the way Republicans cast slavery as the enemy of values like the dignity of labor, the Protestant ethic, social mobility, and economic independence. More than the "convenient rationalization of material interests," moral opposition to slavery, a belief in the cultural superiority of northern society, and an economic interest in the free-soil territory as an area of opportunity for Northern labor all combined to form a coherent free-soil ideology.[8]

Concentrating on the figure of Lincoln, Boritt's "dream" was a similar attempt to combine into a coherent whole the various elements of Lincoln's thought. Boritt attempted to unify Lincoln's career temporally as well, and one of the great triumphs of his book Page [End Page 54] was to show that Lincoln was an unusually principled politician who stood for the same relatively stable set of beliefs throughout his public life.[9] This set of beliefs, or "dream," approached what Richard Hofstadter derisively called "the Self-Made Myth,"[10] and included the belief in rising standards of living, endless material progress and a market orientation, social mobility, and the belief in individual opportunity to rise. (Significantly, Boritt did not include among the elements of Lincoln's dream the ideal of economic independence that Foner had attributed to his fellow Republicans.) [11] Lincoln also shared the labor theory of value common in the period, and, like the Marxists in Europe but unlike most American economic thinkers,[12] this led him to emphasize the rights of labor and to favor the use of strikes to protect the interests of workers. While phrases like "rising standards of living" savor perhaps too much of the twentieth century—and again, Lincoln did not use them—Boritt nevertheless found a consistent pattern of concern in Lincoln's early stand on the national bank, the tariff, internal improvements, public land policy, and, oddly enough, his anti-expansionism. Lincoln was also consistent in later presidential activities, such as military strategy, peacemaking efforts, and his plans for reconstruction. In each of these areas, Lincoln either sought to use public power to advance the opportunities of individuals, especially the poor, to have a fair chance in the "race of life"[13] or made appeals to the economic interests of those whom he sought to persuade. Boritt convincingly showed that for Lincoln, social mobility, equal opportunity, and entrepreneurial market capitalism were normative ideals. "The key to this persuasion," said Boritt, "was an intense and continually developing commitment to the ideal that all men should receive a full, good, and ever increasing reward for their labors so that they might have the opportunity to rise in life." [14] Page [End Page 55]

But Boritt's powerful synthesis of Lincoln's thought into the "American Dream" was somewhat troubled by Lincoln's moralism. For example, the Democrats saw in the acquisition of Mexican territory a possible economic expansion, while Lincoln not only remained impervious to their economic arguments—in the "Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions" and elsewhere—he chided them for their greed and materialism as well.[15] Any casual reader of Lincoln has to be struck by the consistency with which every argument, however technical or legal or economic, took on a moral dimension as well. Boritt clearly recognized this problem and managed it in two ways. First, he noted that for Lincoln, economics itself was a moral science, or rather, that Lincoln's economic arguments always included a self-consciously moral appeal as well. [16] "Lincoln's assignment of a fundamental role to the labor theory makes crystal clear that the moralist in him 'never abdicated before the economist.'... In economic terms, 'useless labour' was the same as 'idleness,' Lincoln explained. Thus, as always in his thinking, economics and ethics merged ..." Lincoln and Marx, Boritt suggested, were both attracted to the labor theory of value because it enabled them to give their economics a moral tone. Secondly, Boritt acknowledged that at certain points in Lincoln's career, economic appeals seemed entirely to disappear in favor of an ethical appeal, as in the case of Lincoln's opposition to Mr. Polk's war, when he "subordinate[d] economic matters to his antiwar stand." [17]

To a certain extent, this latter way of viewing the matter undermined Boritt's effort to unify Lincoln's career on economic principles; and the problem can perhaps best be seen in Boritt's attempt to bring Lincoln's antislavery convictions under the umbrella of the "American Dream." Here Boritt employed both of his strategies for reconciling Lincoln's moralism with the economic dream. First he pointed to the economic arguments Lincoln sometimes employed in making his antislavery appeal and argued that the antislavery appeal flowed naturally from an ethical economics. [18] For instance, Lincoln thought that the Negro ought to have the same right to rise in life and the same right to the fruits of his labor as any other man. Page [End Page 56] This line of interpretation was further strengthened by Lincoln's sometime-characterization of slave masters as "idlers." Boritt made a strong case when he maintained that the same labor-theory/work-ethic moral that permeated Lincoln's economic arguments could be and were applied a fortiori in the case of slavery. Slavery was indeed antithetical to the way of life that Lincoln and the Republicans saw as normative; and on this point Boritt and Foner shine.

The problem with this argument is that there were others who shared Lincoln's belief in material progress, economic opportunity, and all the rest, but who were not antislavery. This applied especially to Stephen A. Douglas. This problem was obscured from Boritt because he used Marvin Meyers' backward-looking and economically unsophisticated Jacksonians rather than the forward-looking Young America of George Bancroft and Stephen Douglas as a foil for his Whig Lincoln: "Lincoln sensed, to borrow the words of Marvin Meyers, that the Whigs tended to speak to the 'explicit hopes of Americans' and the Jacksonians to their 'diffuse fears and resentments.'" [19] Thus as long as it appeared that Lincoln's opponents were "Old Fogies," Boritt could treat forward-thinking entrepreneurial capitalism as inherently antislavery. But by the 1850s, Young America had replaced the Jacksonians as Lincoln's chief ideological opponents. Young America was unambiguously bullish on precisely the economic vision that Lincoln consistently maintained; and yet it was not antislavery. "Douglas Democrats had come to endorse economic development, while Republicans now endorsed the westward movement and had lost interest in the old Whig 'mixed' corporations." [20] The whole internal improvements debate had died down by 1859, not just because the slavery issue overshadowed all else, but because Lincoln and Douglas agreed Page [End Page 57] on the need for railroads and the like. All the more striking then, that Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act in part to facilitate western development and the transcontinental railroad,[21] the very same Nebraska Bill that aroused Lincoln's indignation and fired the soul of the Republican party. Douglas was as much a self-made man as Lincoln, but it was Douglas, not Lincoln, who wanted Americans to put economic development (and political compromise) above morality. According to Boritt,

Boritt's attempt to unify Lincoln's thought on the economic issues of the "American Dream" ignored the fact that even more than Lincoln, Douglas trumpeted the promises of an expanding economy and the American Dream. But it also implicitly assumed that the institution of Negro chattel slavery was something other than market capitalism pushed to an absurd extreme. For Boritt, emancipation "was inherent to the American Dream." [26] Yet for many upwardly mobile Southerners, the American Dream consisted of owning slaves and a plantation; and for Douglas, one man's economic dream was as good as another's. It is difficult to accept the idea that the South was a pre-market society when it increasingly dedicated its economy to producing cotton for a world market and when human beings there were another commodity on the block;[27] and far from sharing in any of George Fitzhugh's Romanticism about a paternalistic Southern way of life, both Lincoln and Douglas saw it as market-driven exploitation.[28] They simply did not see the South as anti-modern in this economic sense. Lincoln well knew that the institution of Negro chattel slavery was of modern origins. When Lincoln made the preamble to the Declaration of Independence into something akin to a statement of faith, and when he made the self-evident truth that all men are created equal into the "central idea of the nation," Boritt was correct to see it as a major reinterpretation of Jefferson; but if Lincoln identified "the right to rise as the central idea of the United States," it is not immediately clear how that excluded the right to rise to the status of slave-owner.[29] Boritt was correct to point out that Lincoln integrated both his Page [End Page 59] economic convictions and this antislavery into a unified vision; and he was right to point out that Lincoln maintained this integrated vision consistently throughout his career. But there was nothing anti-capitalist about Southern chattel slavery—George Fitzhugh notwithstanding—and thus the sources of Lincoln's antislavery arguments are not to be found in his economic vision. Rather his antislavery convictions and his economic thinking shared a more fundamental common source.

Sensing this, the second strategy Boritt employed for reconciling antislavery moralism and the economic dream was simply to concede that Lincoln's moralism was more fundamental than his economics. Though it ran counter to his thesis, Boritt pointed out that Lincoln even downplayed the appeal to Northern economic interest in the free-soil cause because "he recognized that emphasizing materialistic self-interest weakened his high moral tone." "Lincoln's opposition to slavery," Boritt further conceded, "was expressed in moral terms, and he raised the moral ingredient of politics perhaps to its highest level in the dominant stream of American politics. Under the all-important moral superstructure, however, he often buttressed his thought with economics—not surprising for one who had placed the good science at the heart of his efforts for more than two decades."[30]

Boritt began his investigation into Lincoln's economic thought because he observed that so much of Lincoln's writing either treated economic issues or treated the economic dimension of issues that might otherwise be seen in political or legal ways; and this alone was a major contribution. But from this he moved to make an economic vision the conceptual center of Lincoln's thought. Lincoln clearly addressed economic, or legal, or political issues as they arose; and since many if not most of the issues that confronted him as a frontier legislator centered around economic development, economics necessarily occupied much of his time. As Boritt himself put it, "of course improvements, for [Lincoln] and many others, were ultimately part of broad advancement that was 'material, moral, intellectual,' to quote his words from 1859. The material road was merely the means leading toward intellectual and moral elevation. But while we cannot say that even as a youth he let the ultimate goals out of sight, he did concentrate the bulk of his energies on the material road. He was, after all, a politician in a state where economic battles were also the main political battles." Or Page [End Page 60] again: "For the first period of [Lincoln's] political life economics provided the central motif. Antislavery was also there but was pushed far in the background with its triumph placed at a very distant day. After 1854, antislavery became Lincoln's immediate goal, and the economic policies that he continued to esteem highly and work for when possible were relegated to the background and to a future triumph." [31]

There was a dangerous ambiguity in the way Boritt used such modern phrases as "rising standards of living," or "endless material progress." Since these phrases come from the twentieth century, they have their roots and their meaning in the context of a twentieth-century economy in which large numbers of people work their entire lives as employees. But in 1861, Lincoln could still deny that a system of permanent wage labor even existed![32] Boritt downplayed the ideal of "independence" when he summarized Lincoln's economic dream, in part because he needed Lincoln's dream to be more modern, and in part because he associated "independence" with the Jeffersonian ideal of the yeoman farmer, an ideal that Lincoln explicitly rejected.[33] At the Wisconsin State Fair, Lincoln refused, as he said, "to employ the time assigned me in the mere flattery of the farmers, as a class. My opinion of them is that, in proportion to numbers, they are neither better nor worse than other people."[34] According to Boritt, Lincoln favored the small producer more for "Whig-Republican economic" reasons than for "Jeffersonian socio-political" ones; and with this he discounted the "pre-modern" elements of Lincoln's economic thought, the very ethical dimension that continually led Boritt to qualify his thesis almost out of existence. [35]

Boritt slighted the fact that, though it had little to do with Jefferson, there was a kind of independence that was important for Lincoln and the Republicans; and this "moral independence" rather than the more modern sounding "American Dream" is a better Page [End Page 61] choice for naming and organizing Lincoln's economic views. Lincoln's economic thought represented a middle term between the static world of Jefferson's imagination and what we like to call "modern" economic relationships. The opportunity to rise, for Lincoln, meant that "many independent men everywhere in these States, a few years back in their lives, were hired laborers."

Boritt was right to drive a wedge between the world of Jefferson and the world of Lincoln. The shift from the Jeffersonian ideal to the self-made man of Lincoln's imagination was of historic importance. Boritt noted that Lincoln's arguments in favor of a high protective tariff "took part of the tendency of protectionist thinking to move away from the politically oriented tariff policy of Hamilton and the generation that followed him, which had an air of apologia, a call to sacrifice, about it."

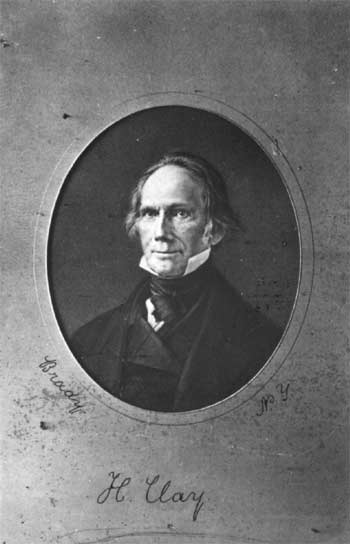

If by the 1820's Clay came to base his case ever more on economic grounds, considerations of political independence, national welfare, the safety of the Union, and such, were still salient to his thinking. For Lincoln, and somewhat less so for his whole generation, the appeal to economic interest became the judicious stand. Indeed the abandonment of an economics whose ultimate goals were political, for one with frank socio-economic aims, constitutes the basic difference between his political economy and that of the old Whigs.

The economic revolution that came to the United States during the middle third of the nineteenth century, and which co- Page [End Page 63] incided with the growth of the nation's political security, produced this change in thought patterns. Americans developed an increasingly candid materialistic outlook even as the memories of the wars against England grew dim and a new emphasis on sectional loyalty arose in their stead.[42]

It is true that even more than Henry Clay, Lincoln based his arguments on the welfare of individuals. He rarely, if ever, used the classical republican language of public virtue; and for him, the concept of "disinterestedness" so crucial to republican thinking amounted to a theological absurdity. [49] (Lincoln extended a notion of original sin or natural depravity to everyone, including both "the people," and any pampered elite.) Thus Boritt was correct to point out that the vocabulary of classical republicanism and disinterested virtue was absent in Lincoln's writings. But although Lincoln's economic appeals sound forthright to our ears, once again Boritt stumbled over Lincoln's moralism and found himself forced to add that Lincoln's economic arguments "never overshadow[ed] his moral perception."[50]

It does not follow that because Lincoln rejected republican language he could only have been the forthright Epicurean liberal (albeit one with a quirky moral streak) of Boritt's American dream—and this is of tremendous historiographical significance. Before the cult of scientific expertise rose in the late nineteenth century to replace it, Protestant categories again dominated the American imagination, and this was true not just for evangelicals, but for young intellectuals like Lincoln as well. While the Old Fogy rhetoric of inherited wealth and classical virtue seemed wooden and even petrified in a wide-open opportunity economy, Protestantism remained alive and well. Not only did the Romantic, anti-Enlightenment tendencies of the time lend renewed intellectual respectability to religious thought—witness educated Brahmins like Emerson and Bancroft—but the evangelical movement "manifested a resurgence of middle-class Protestant culture." [51] Protestantism had always remained a potent intellectual force outside of the Page [End Page 65] elite cosmopolitan circles—even in Jefferson's day; thus the election of Jackson that ended elite domination of political debate contributed to the rise of a more overtly religious political discussion as well. As a self-educated intellectual from the bottom of border-state and then Illinois society, Lincoln was perfectly positioned to take part in these tendencies. Whigs accepted the new social mobility; nevertheless they attempted to temper the spirit of unbridled acquisitiveness with appeals to what they imagined were the higher ends of man. Increasingly, they based that appeal on religious grounds. Lincoln's religious utterances reflected this orientation.

While he noted this significant shift in Lincoln's thought away from the residual republican ideas still detectable in the thought of Henry Clay, Boritt played up Lincoln's affinity for Clay and simultaneously downplayed any resemblance between Lincoln and the evangelical wing of the Whig and later Republican parties. Lincoln, he said, "was not an evangelical Christian, indeed no formal Christian of any sort. It can be argued that he shared certain social values that can be broadly termed evangelical. Lincoln did speak on behalf of temperance, for example, but as with abolitionism, he was much too moderate a man to be one of the true faithful." (The assumption is of course that no moderate man could be truly faithful.) Boritt also noted that "Lincoln did not partake of the nativist proclivities that contemporaries as well as subsequent students diagnosed among the Whigs (and eventually among the Republicans) ... [and] Lincoln's attitude toward schools, another modern yardstick of Whiggery, was at best ambivalent." Lincoln also rejected the elite snobbery of "silk-stocking" Whiggery. At the same time, he professed great admiration for Clay; and Boritt attributed this, no doubt correctly, to the politically moderate antislavery views shared by both men, to the positive government impulse of Clay's American System, and to the ideals captured admirably in that star-fated coinage of Clay's, the phrase "self-made man." [52] But while silk-stocking elite leadership and the classical republican rhetoric of disinterested "virtue" were rapidly waning, a Protestant vision increasingly replaced those more secular-seeming ideals in the three decades before the Civil War. Lincoln received the overwhelming support of Protestant religious groups in 1860 and 1864.[53] He was elected by skilled workers and Page [End Page 66] professionals who felt they had the most to gain from the economic prosperity of market capitalism, by native-born farmers, and by voters of New England descent. [54] His rhetoric reflected this constituency perfectly: he combined the forward-thinking, pro-development, and positive-government Whiggery of Clay's American System with the moral concerns of New England and of the evangelical movement.

In the Wisconsin State Fair speech, Lincoln painted a vivid picture of what he meant by "free-labor," and in it he associated permanent wage labor with the "mud-sill" theory put forth by slavery apologists like George Fitzhugh. By the 1850s, Southerners had begun to defend slavery with a claim that the slave was better off than a factory worker because they were cared for in old age, and because a slaveholder had an interest in caring for his "property," which the factory owner could not have. [55] Implicitly accepting the premise of the Southern argument, Lincoln conceded that a permanent wage-labor system would be unacceptably oppressive. He therefore had to deny that a system of permanent wage-labor existed in the North at all. Lincoln's understanding of the Northern economy reflected his own experience as a successful man who rose almost from the bottom of the social ladder; he believed in the right to rise. But "free labor" was not permanent wage-labor; it was neither the necessary drudgery of lower orders, as it was in classical republican thought, nor was it the somewhat unpleasant means to material acquisition, as it is in modern economic thought. Labor for Lincoln was a divine "charge" with its own ends. At the state fair he encouraged farmers to adopt modern agricultural techniques of "thorough cultivation:"

By the "mud-sill" theory it is assumed that labor and education are incompatible; and any practical combination of them impossible. According to that theory, a blind horse upon a tread-mill, is a perfect illustration of what a laborer should be—all the better for being blind, that he could not tread out of place, or kick understandingly. According to that theory, the education of laborers, is not only useless, but pernicious, and dangerous. In fact, it is, in some sort, deemed a misfortune that laborers should have heads at all. Those same heads are regarded as explosive materials, only to be safely kept in damp places, as far as possible from that peculiar sort of fire which ignites them. A Yankee who could invent a strong handed man without a head would receive the everlasting gratitude of the "mud-sill" advocates.

But Free Labor says "no!" Free Labor argues that, as the Author of man makes every individual with one head and one pair of hands, it was probably intended that heads and hands should cooperate as friends; and that that particular head, should direct and control that particular pair of hands. As each man has one mouth to be fed, and one pair of hands to furnish food, it was probably intended that that particular pair of hands should feed that particular mouth—that each head is the natural guardian, director, and protector of the hands and mouth inseparably connected with it; and that being so, every head should be cultivated, and improved, by whatever will add to its capacity for performing its charge. In one word Free Labor insists on universal education. [57]

This is not to say that he was the captive of some dogmatic religious rule, or that he blindly accepted some article or other of faith; in almost all areas Lincoln was a remarkably independent thinker who, even when he used the ideas of others, insisted on sharpening their formulations and passing them through his own filters. Rather he had a sense of human experience and psychology that was simply too rich and subtle for the self-interested calculus of Bentham, or, for that matter, Bentham's neo-classical, "Chicago School" imitators of a latter day. "The leading rule for the lawyer, as for the man, of every calling, is diligence,"[59] he said. The term "calling" still implied service to God, and by invoking it Lincoln placed himself in a tradition of providential thought about the human condition. He tended to overwork himself not out of a desire to gain, or even to "get ahead," but rather out of a constant and pressing sense that his life had to have a higher meaning and that that meaning was to be found chiefly in what a less theological age would call his "career." He was too much of a Romantic to accept material acquisition as a legitimate purpose in life. He was well aware of his superior talents, and his "ambition" was to find a worthy outlet for them. Lincoln was subject to depression when he felt his career was faltering, and he knew whereof he spoke when he talked about doing the work well only when the heart was in it. Like Francis Wayland, Lincoln too quoted Genesis: "in the sweat of thy face, shalt thou eat thy bread;" and unlike Wayland, he turned this argument against the slaveholders. [60] Permanent wage-labor with a rising material standard of living was explicitly not a part of Lincoln's "dream." Thus in the analysis of Lincoln's economic thought, the anachronistically materialistic elements of Boritt's "dream" should be replaced by the right—indeed the divinely appointed duty—to labor in one's calling, and to rise therewith to moral autonomy and economic "independence." Page [End Page 69]

Not surprisingly, much of Lincoln's economic thinking followed that of the chief Whig economic theorist and apologist for the tariff, Henry C. Carey. [61] Carey worked within the idiom of moral philosophy; he was optimistic about human nature; he rejected the conclusions of Malthus in part because a beneficent deity just would not act that way; and any reformed theology in his thought was much more muted and unitarian than it was in Lincoln's. [62] Still the content of his economic ethics bears striking resemblance to Lincoln's, and some of the details of Lincoln's economic thought, like his preference for small land holdings, strongly indicate a direct influence of Carey on Lincoln. [63] In Carey's writings, Lincoln found support for his Whig position on internal improvements and the tariff. [64] Like Lincoln, Carey refused to accept any caricatured economic man in his analysis. [65] Instead he sought to determine whether the course of history "tended in the direction of developing the qualities which constitute the real man, the being made in the image of his Creator, fitted for becoming master of nature and an example worthy to be followed by those around him; or those alone which he holds in common with the beasts of the field, and which fit him for a place among men whose rule of conduct exhibits itself in the robber chieftain's motto, 'that they may take who have the power, and those may keep who can.'"[66] Like Lincoln in the speeches of 1858 and 1859, Carey thought in terms of an ongoing economic and technological revolution. Malthus was wrong; in industrial society, greater population meant greater wealth. Thus through technological advancement, the dismal science would be overcome. Like Lincoln, Carey rejected the Jeffersonian ideal of a yeoman-farmer citizenry. And like Lincoln, he favored industrial development. "Highest, therefore, among the tests of civilization," he declared, is whether society "enables all to find demand for their Page [End Page 70] whole physical and mental powers." Because people's powers differed, "diversity of employments" was essential. Only a diversified economy that included industry could provide such varied career opportunities.[67] In stark contrast to Jefferson, Carey and Lincoln found farm life in the nineteenth century stultifying. Carey also sought the liberation of women from the drudgery of the household in the employments of a diversified economy. While Carey and Lincoln both rejected the constraints of the old apprenticeship economy that doomed individuals to the trades and callings of their parents and that favored deference to hereditary elites, they also rejected an economics that made money and material the measure of all things. This was the forward-thinking Whig message, and abolitionists and Temperance advocates joined the Whigs in their admiration of entrepreneurship. [68] In this narrow window of American history, it was possible to justify market capitalism on the grounds of higher human aspirations.

The differences between Carey and Lincoln highlight the new Romantic sensibility present in Lincoln but not in Carey. And this is most readily seen in the different ways the two men treated history. For Carey, history was a kind of myth, not unlike the mythic natural histories characteristic of Enlightenment thinkers like Locke, Rousseau, and Smith. The point of those imaginary natural histories was usually to show how, beginning with a state of nature, the workings of certain fundamental and knowable natural laws (and often their subsequent subversion by "unnatural" forces) had led to the present. Real history could be dismissed as irrelevant while this imaginary replacement-history was reconciled with the assumption of timeless postulates. Carey's The Past, the Present & the Future of 1847 was an elaborate installment in this by then much-hallowed genre. Carey saw history being repeated over and over again much in the same way that Frederick Jackson Turner would in his treatment of the frontier. [69] Carey began with "the first cultivator, the Robinson Crusoe of his day, provided however with a wife ..." and returned to this quaint, if overused image, at the beginning of each of his chapters.[70] Though further on in most Page [End Page 71] of his chapters he eventually rose to concrete historical examples, these were only invoked to illustrate universal principles. The natural laws of economics working everywhere in the same manner resulted not in a diminishing food supply and misery, but in the rising standard of living that allowed individuals to pursue ever-higher degrees of self-development.

Carey praised the United States

Carey's "scientistic" method of proceeding contrasted starkly with Lincoln's lectures on "Discoveries and Inventions." In the Discoveries and Inventions lectures, Lincoln gave a genuinely historical account, including such concrete events as the advent of printing and the Protestant Reformation. [73] The past was not like the present (minus of course corruption and priestcraft usually invoked to explain why the present was better). Rather, the invention of printing and the Reformation made possible a new way of thinking. Even in his survey of the Old Testament, Lincoln did not seek a kind of mythic history that in some form had taken place over and over again throughout time. Instead he looked to date singular inventions, such as boats and spinning wheels. If Dorothy Ross is correct, most American social thought has entailed an "exceptionalist" view of America that has been essentially Enlightenment in its static view of nature and, therefore, anti-historical. [74] In the exceptionalist view, America represents an escape from history into a natural order; and even many of America's most prominent historians have been, at core, anti-historical. As Ross put it, "Romanticism ... provided fuller appreciation of the particular configurations of the historical world. Emerging in reaction to the Enlightenment attempt to subject all reality to universal and mechanistic general laws, the romantics grounded value and sought intelligibility in the individuality and diversity of historical existence." [75] This, then, may be the most important point to be gained from Lincoln's "Lectures on Discoveries and Inventions": Lincoln's biblically minded view of history was in fact historicist; it was therefore at odds with most American social science, including most especially American economic thought. Page [End Page 73]

Lincoln shared fully in the American Romantic and his life-work represented one of its highest achievements. "Given the timidity of the colleges, and practical energy of American politics, and the diffuseness of the subject, it is perhaps not surprising that the most influential formulation of political science before the Civil War should be the work of a German immigrant," Francis Lieber.[76] While the colleges were still under the sway of the old Scottish moral philosophy, the leading intellectuals either came from Germany—Lieber and Schaff; rejected their Enlightenment schooling explicitly, often under the direct influence of German ideas—Emerson, Bancroft, Hawthorne, Poe, Parker, Bushnell, and John Nevin; or were autodidacts—Melville, Thoreau, Whitman, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. And in an age of great autodidacts, Lincoln was chief among them. Though he borrowed heavily from Carey, including the belief that Malthus was wrong and that progress could go on indefinitely, Lincoln imagined history in an entirely different manner, and this placed him squarely in the new Romantic movement.

Though there is much justice in the speculation that, had he survived, Lincoln would have sided with labor in the upheavals of the late nineteenth century, he did not see permanent wage-labor as a reality, and he did not see those upheavals coming. Daniel Walker Howe has suggested that, had he lived, Lincoln may well have shared Carey's deep disquiet over the economic developments of the post-war period.

On the other hand, Phillip S. Paludan has warned us that we should know Lincoln "as a man of his age, not as a man too good for it."[79] When Southern apologists, most notably George Fitzhugh, attacked the Northern free-labor system by citing abuses like child labor and long factory hours that led to a life of harsh subsistence, Lincoln reacted as defensively to these attacks as Douglas had to aspersions cast on the ethics of American expansion. "Republican politicians and abolitionists were stung by this critique and as Lincoln's partner William Herndon recalled, 'Sociology for the South aroused the ire of Mr. Lincoln more than most pro-slavery books.'" [80] Even while Lincoln actively worked to increase opportunities for men like himself to rise, he was also led, somewhat inconsistently, to mistake his free-labor ideals for the realities of antebellum life. In this limited way, slavery may have blinded Lincoln to the emerging problems of industrialization that, as Paludan pointed out, others of Lincoln's time saw more clearly. Dickens, Hawthorne, Melville, Thoreau, and Emerson all had reservations about the direction economic development was taking, while Lincoln, in the act of mustering Northern self-confidence for the antislavery battle, took little note of such nay-sayings. And Lincoln's belief in the reality of social mobility was not without its harsh side. Perhaps we see Lincoln at his worst in his dealings with his own family, people who from Lincoln's point of view at least, failed to do the things that would have led to greater personal economic success and who he may therefore have felt justified in leaving behind.[81] As Paludan noted, but for the war William Sherman and Ulysses Grant would have remained floundering on the frontier just like Lincoln's less successful relations. At times Lincoln might have shown more understanding of the economic realities and difficulties of his day; and it seems that hubris, Lincoln's pride in hav- Page [End Page 75] ing come up from the bottom on his own, at least partially blinded him to the fact of his extreme good fortune.

Still Lincoln did work to make economic opportunity a reality; and because the slavery issue necessarily distracted his entire generation from economic issues that otherwise might have absorbed more of their attention, it does not follow that antislavery was a smoke-screen for Northern industrial development. In the twentieth century, even the Left has generally accepted the materialistic assumptions of capitalism. Thus somewhat ironically, Lincoln and the Whigs submitted their economic system to an ethical critique rather more stringent than we have tended to apply since.

After apologizing, in effect, for Lincoln's preoccupation with the issue of slavery and his subsequent inability to anticipate the problems of industrialization, Boritt added that,

After recognizing the Lincolnian failures, it should still be emphasized that to the end of his life Lincoln continued to move toward the future—sometimes quite alone. The essential part of his thought was improvement, the advancement of the independent farmer-workingman-entrepreneur was only the chief means. The latter's inevitable eclipse, we know now, did not have to diminish the right to rise. On the contrary. As industrialization entered a stage with which Lincoln had little first-hand familiarity, as factories and increasingly mechanized farms came to dominate the land, new opportunities opened up. Mobility in the direction of economic independence was replaced by mobility toward higher standards of living, and higher positions in the management scale, in a wage-earning society. Lincoln's understanding of this coming change was very restricted, but it permitted him to maintain his support of economic development unwaveringly [emphasis added]. Indeed, the assumption that development increased mobility was so fundamental to him that by the late 1850s, with most of his political career behind him, it is no longer enough to say that he favored development and expanding productivity because it helped people to rise in life. He also favored the right to rise because it led to development.

Thus in spite of his eloquent support of the small, independent producer that dominated his America, Lincoln could continually adjust his sights to the changing world around him. [82] Page [End Page 76]

Boritt himself pointed out that as Lincoln worked to bring the giant railroad corporations into being, he seemed to have had a "totally innocent lack of foreboding" regarding large-scale capitalist enterprise. [84] These large corporations would soon transform his world of small independent entrepreneurs into a Gilded Age of big labor and big capital. More than this, though the Civil War separates the Romantic antebellum period from the harsh scientism, social Darwinism, and literary "realism" of the Gilded Age, Lincoln prosecuted the war to preserve that older world of moral and economic independence. Thus it can hardly be said that Lincoln's vision "triumphed," and in making Lincoln "the first American," he should not be made into one of us.

As Eric Foner put it, "The foundations of the industrial capitalist state of the late nineteenth century, so similar in individualist rhetoric yet so different in social reality from Lincoln's America, were to a large extent laid during the Civil War. Here, indeed, is one of the tragic ironies of that conflict. Each side fought to defend a distinct vision of the good society, but each vision was destroyed by the very struggle to preserve it."[85] Despite laudable efforts to avoid this problem, there remained hidden in Boritt's vocabulary of the American Dream and "the American way of life" [86] an unwarranted projection of the American present onto the screen of Page [End Page 77] the past. We tend to view the past as a quaint version of the present striving to be more like us. Thus, from Bancroft on, we have eliminated all tragedy, including tragically, Lincoln's.

Because Lincoln and his generation did not have modern American life in mind when they unwittingly set its big industrial wheels in motion, it is inappropriate to read them as cheerleaders of the American way of life as we know it. But it is especially disturbing in view of Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address. Lincoln in particular almost always maintained a critical, even prophetic, stance toward the society he knew, and in places Boritt acknowledges this.[87] Yet in the end this tragic dimension was lost in Boritt's account:

In 1859, when he necessarily had to make the strongest case he could for the Northern way of life and its free-labor economy, Lincoln came the closest he ever would to claiming God's particular favor for American institutions. [89] Even then he was able to discriminate between the free-labor he celebrated and the real existing New England factory system. Like English Romantics such as Carlyle and Blake, Lincoln could ask the prophetic question: "was Jerusalem builded here, amid these dark satanic mills?" And by the time he wrote his Second Inaugural Address, he denied outright that God's purpose could be equated with our own.

Nevertheless Boritt carried his economic interpretation to the Second Inaugural:

It is fair to say that we have lost much in the way of theological discernment and sophistication in the last century and a half. Where a man of Bancroft's day could dream, however foolishly, that "the husbandman or mechanic of a Christian congregation solves questions respecting God and man and man's destiny, which perplexed the most gifted philosopher of ancient Greece," a trained academic historian of the late twentieth century can misread even the surface-level theology of Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address: quoth Lincoln, "the Almighty has His own purposes." Boritt remarked at one point that among the factors that led to the Emancipation Proclamation should be added Lincoln's "perception of the will of God."[91] Though one can doubt the validity of one's perception, as Lincoln did, and though one can doubt one's authority to act on those perceptions, as Lincoln did, one's perception of the will of God cannot be given a subordinate role or even the coequal status of "another factor." It is by definition the most comprehensive viewpoint.

The point is not to slight a historian whose book for good reason remains on the shortest shelf of essential Lincoln readings, but rather to emphasize how far from the world of Lincoln we have come: Rather than the repository of his deepest gut-level ruminations, Lincoln's religious vocabulary could only be for us the sign of a soft head. By imputing to Lincoln the idea that America was "this light unto the world," and by putting forward the thesis that Lincoln equated his own purposes with the will of God, we misapprehend the Second Inaugural Address, misjudge the character of its author, and miss one of his keenest, most fundamental insights.

By referring to Lincoln's economic orientation, Boritt discovered considerable continuity in Lincoln's thought before and after the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. But he saw that "such continuity [could] also be detected by focusing on his religious, or stylistic Page [End Page 79] development; or by limiting the inquiry to his expressions concerning political processes." [92] We have seen that Boritt's "economic dream" failed to synthesize important political, moral, and religious elements of Lincoln's thought into a coherent whole. It is true that politics and political economy were moral enterprises of Lincoln, and for us, this observation is the most important point to be gained from Boritt's book. Thus Boritt's interpretation was much stronger for its honest reservations than for its thesis.

The younger generation of Whigs, the men who later provided the intellectual leadership of the Republican party in the 1850s, belonged to a different world than even John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun. In this brief period, the Romantic held sway in American public discourse. Romantics tended to look to the religious thought of the past for inspiration, and since for many the American past was, roughly speaking, Calvinist and even Puritan, American Romantics returned to Reformed understandings of the human condition, reactivated and revitalized them, and inevitably, adapted them to their own purposes. The religious feeling of the period lends the Civil War its particular flavor, and as much as any other factor, this pathos probably helps explain the war's enduring appeal to readers of history.[93] Thus if we want to recover the full colors even of Lincoln's economic thinking, we must explain this religious dimension of Whig and Republican thought as well. Though their overall economic outlook differed greatly from that of their Puritan forbears, Lincoln and his generation reactivated the idea of "calling" and adapted it to the socially mobile, opportunity economy that existed just prior to the rise of mass industrialization. They made moral independence and "calling" the goal of political economy, and this should replace "the American Dream" in our understanding of the period. Page [End Page 80]

Notes

-

Gabor S. Boritt, Lincoln and the Economics

of the American Dream (1974; reprint, Urbana: University of

Illinois Press, 1994), 71.

-

Ibid., 240.

-

Daniel Walker Howe, The Political Culture

of the American Whigs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1980), 302.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 11.

-

Howe, Political Culture, 9.

-

George Bancroft, Literary and Historical

Miscellanies (New York: Harper & Brothers), 515–16.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 252.

-

Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free

Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 9, 261, 5, 13–16.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics,

viii–ix, 278, 30, 43, 78.

-

Richard Hofstadter, The American

Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (1948; reprint, New

York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974), 118.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 11,

117, 185–88.

-

Joseph Dorfman, The Economic Mind in

American Civilization, 1606–1865, vol. 2 (New York:

Viking Press, 1946), 967, passim.

-

Roy P. Basler, ed., Collected Works of

Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers

University Press, 1953–1955), 7:512 (hereafter cited as

Collected Works); Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 278;

Don E. Fehrenbacher, ed., Lincoln, Speeches and Writings,

1859–1865 (New York: Literary Classics of the United

States, 1989), 624.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, ix.

-

Collected Works, 3:356–63;

Fehrenbacher, Lincoln, Speeches and Writings, 2:3–11.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 58,

103.

-

Boritt cites Edmund Wilson, To the

Finland Station: A Study in the Writings and Acting of History

(New York: Doubleday, 1953), 298. Boritt, Lincoln and

Economics, 113, 142.

-

Ibid., 58, 103, 113, 193.

-

Ibid., 20–23, 64, 67, 77, 22; Marvin

Meyers, The Jacksonian Persuasion (1957; reprint, New York:

Stanford University Press, 1960). On Young America, see Robert

Johannsen, Stephen A. Douglas (New York: Oxford University

Press, 1973), 144; Johannsen, "Young America," chap. 15 in

Stephen A. Douglas. David S. Spencer, Louis Kossuth and

Young America: A Study of Sectionalism and Foreign Policy,

1848–1852 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1977),

262; John Stafford, The Literary Criticism of "Young

America" (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952), 259;

Edward L. Widmer, Young America: The Flowering of Democracy in

New York City (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 440;

Merle E. Curti, Probing Our Past (New York: Harper, 1955),

170.

-

Howe, Political Culture, 289. Howe

nevertheless continued to see in "Jacksonians" like Douglas a

"pre-modern" animus; see page 300.

-

Michael F. Holt, Political Parties and

American Political Development from the Age of Jackson to the Age

of Lincoln (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press,

1992), 316–17.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 234.

-

Speech of Senator S. A. Douglas at the

Meeting in Odd-Fellows' Hall, New Orleans, on Monday Evening,

December 6, 1858 (Washington, D.C.: L. Towers, 1859).

-

Davis J. Greenstone, The Lincoln

Persuasion: Remaking American Liberalism, (Princeton, N.J.:

Princeton University Press, 1993), 232.

-

Collected Works, 3:366–67;

Fehrenbacher, Abraham Lincoln, Speeches and Writings,

1859–1865, 13–14.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 256,

162, 175.

-

For the debate on the nature of American

slavery, see Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman, Time on the

Cross (Boston: Little, Brown, 1974), Eugene Genovese, The

World the Slaveholder Made (New York: Pantheon, 1969), and

Kenneth Stampp, The Peculiar Institution (New York: Knopf,

1956).

-

Collected Works, 2:351; Boritt,

Lincoln and Economics, 163; Collected Works, 3:349.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics,

160–62.

-

Ibid., 164, 163.

-

Ibid., viii, 8, 155–56.

-

Collected Works, 5:52; Fehrenbacher,

Lincoln, Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, 296. For a

critique, see Phillip S. Paludan, "Commentary on Lincoln and the

Economics of the American Dream," in The Historian's

Lincoln, ed. G. S. Boritt (Urbana: University of Illinois

Press, 1988).

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics,

185–89.

-

Collected Works, 3:472; Fehrenbacher,

Lincoln, Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, 91.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 188.

-

Collected Works, 5:52–53;

Fehrenbacher, Lincoln, Speeches and Writings,

1859–1865, 296–97.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics,

181–85, 218–21.

-

Dorfman, Economic Mind, 699.

-

Howe, Political Culture, 101.

-

Francis Wayland, The Elements of Moral

Science (New York: Cooke, 1835), The Elements of Political

Economy (Boston: Gould, Kendall & Lincoln, 1837), and

The Elements of Intellectual Philosophy (Boston: Phillips,

Sampson, 1854).

-

Joel Porte, ed., Ralph Waldo Emerson,

Essays & Lectures (New York: Literary Classics of the

United States, 1983), 260, 275.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics,

117–18.

-

Joyce Appleby, Capitalism and a New

Social Order (New York: New York University Press, 1984), 4.

-

Louis Hartz, The Liberal Tradition in

America (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1955), 3.

-

John P. Diggins, The Lost Soul of

American Politics: Virtue, Self-interest, and the Foundations of

Liberalism (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 62.

-

Appleby, Capitalism and New Social

Order, 3.

-

Lance Banning, "Jeffersonion

Ideology Revisited: Liberal and Classical Ideas in the New American

Republic,"William and Mary Quarterly 43 (Jan.

1986): 3–34.

-

Howe, Political Culture, 280, 299.

-

Diggins, Lost Soul, 3–17.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 118.

-

Howe, Political Culture, 155.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 97,

98, 99.

-

David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New

York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 542.

-

Ibid., 544.

-

Dorfman, Economic Mind, 907;

Fehrenbacher, Lincoln, Speeches and Writings,

1859–1865, 84.

-

Collected Works, 3:475; Fehrenbacher,

Lincoln, Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, 94.

-

Collected Works, 3:479–80;

Fehrenbacher, Lincoln, Speeches and Writings,

1859–1865, 98–99.

-

Thomas Bender, ed., The Antislavery

Debate: Capitalism and Abolitionism as a Problem in Historical

Interpretation (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1992), 19.

-

Collected Works, 2:81; Don E.

Fehrenbacher, ed., Abraham Lincoln, Speeches and Writings,

1832–1858 (New York: Literary Classics of the United

States), 245.

-

Collected Works, 8:333; Fehrenbacher,

Lincoln, Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, 687;

Collected Works, 1:411–12; Wayland cited in Boritt,

Lincoln and Economics, 123 and 333 n. 19.

-

Howe, Political Culture, 265. Much of

this discussion of Carey follows Howe, 108–22.

-

Henry S. Carey, Principles of Social

Science, vol. 1 (1858; reprint, Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott,

1888), 463, quoted in Howe, Political Culture, 114; Dorothy

Ross, The Origins of American Social Science (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1991), 47.

-

Collected Works, 3:475; Carey,

Principles of Social Science, 470; Fehrenbacher, Lincoln,

Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, 94.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics,

121–25.

-

Howe, Political Culture, 111.

-

Henry C. Carey, The Unity of Law, as

Exhibited in the Relations of Physical, Social, Mental, and Moral

Science (Philadelphia: Henry Carey Baird, 1872), v.

-

Carey quoted in Howe, Political

Culture, 111; ibid., 112.

-

Greenstone, Lincoln Persuasion, 252.

-

Frederick J. Turner, The Significance of

the Frontier in American History (1893; reprint, Manchester,

N.H.: Irvington), 1993.

-

Henry C. Carey, The Past, the Present

& the Future (1847; reprint, Philadelphia: Henry Carey

Baird, 1872), 5.

-

Ibid.

-

Ross, Origins of Social Science,

33–37, 44–45, 23.

-

Collected Works, 3:361–62.

-

David Noble, Historians against History:

The Frontier Thesis and the National Covenant in American

Historical Writing since 1830 (Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1965).

-

Ross, Origins of Social Science, 9.

-

Ibid, 38.

-

Howe, Political Culture, 297, 122.

-

Ibid., 297.

-

Paludan, "Commentary on Lincoln and

Economics," 120.

-

Ibid., 120.

-

Charles Hubert Coleman, Abraham Lincoln

and Coles County, Illinois (New Brunswick, N.J.: Scarecrow

Press, 1955).

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics,

180–81.

-

Thomas F. Schwartz, "Lincoln Never Said

That," For the People: Newsletter of the Abraham Lincoln

Association 1 (1):4–6.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 128.

See also Hofstadter, American Political Tradition,

135–36.

-

Eric Foner, "The Causes of the American

Civil War," in Politics and Ideology in the Age of the Civil

War (London: Oxford University Press, 1974), 33.

-

Boritt, Lincoln and Economics, 127,

155.

-

Ibid., 179–80, 218.

-

Ibid., 284.

-

Ibid., 179–80, 218.

-

Ibid., 284.

-

Ibid., 256.

-

Ibid., 157.

-

Perry Miller, Nature's Nation

(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967), 120.