Salmon P. Chase and the Politics of Racial Reform

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Review Essay

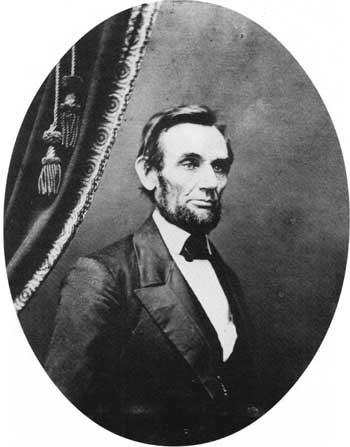

At least for a generation, since the enactment of historic civil rights legislation in the 1960s, the nineteenth-century origins of racial reformism have commanded the attention of historians. [1] Because a national civil rights policy effectively began with military emancipation and other events in which he played a central role, the views of Abraham Lincoln on race relations and civil rights have been studied for the light they throw on racial reformism. Yet Lincoln arguably is not the best source for the study of racial reformism. To understand why this is so, we might consider that Lincoln has sometimes been perceived as a revolutionary but seldom as a reformer. [2] One of the most important speeches expressing Lincoln's political philosophy, the Temperance Address of 1842, presents a searching critique of the attitude and methods of the reformers of his day.[3] To put the matter more directly, Lincoln was concerned Page [End Page 22] with larger matters than the abolition of slavery and the reform of race relations in the United States.

The ultimate issue for Lincoln was not the nature of slavery as an evil or unjust institution, as it was for abolitionist reformers. It was the place of slavery in American life and its effect on the polity. In Lincoln's ordering of priorities, the fundamental problem was to preserve the Union and create a nation. After the attack on Fort Sumter, emancipation was, for Lincoln, a means of winning the war, whereas for antislavery reformers the war was a means of promoting emancipation. If Lincoln was not a reformer, however, he was surrounded by reformers in the Republican Party. And he had to deal with a very famous reformer in his cabinet, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase.

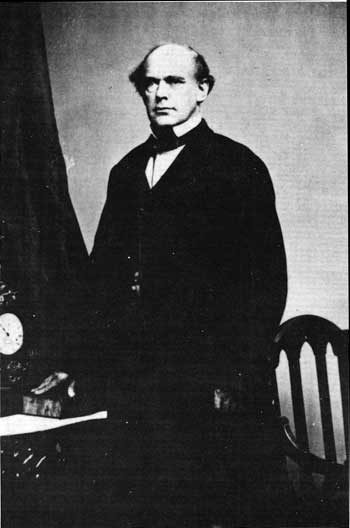

Chase, as senator from Ohio from 1849 to 1855, had the distinction of being the first member of the U.S. Senate elected as a political abolitionist not a member of either of the two major parties. After serving as Republican governor of Ohio from 1856 to 1860, Chase was again elected senator from Ohio to the Thirty-seventh Congress. As a renowned antislavery politician, however, Chase deserved a place in the Lincoln administration, and, giving up his Senate seat, he was appointed and served as secretary of the treasury until resigning in June 1864. Upon the death of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, Chase was appointed chief justice of the Supreme Court, the office he occupied until his death in 1873.

By definition perhaps the perspective of biography precludes the kind of systematic and comprehensive inquiry on which historical explanation depends. A biographical perspective is nevertheless essential for historical understanding, for, ultimately, it is the ideas, decisions, and actions of individuals that give texture and definition to the events of history. If we wish, therefore, to understand the nature and tendency of racial reformism as a continuing theme in American politics, it behooves us to study the lives of racial reformist politicians.

Although I do not suppose, nor does it appear, that John Niven writes with this purpose in mind, his Salmon P. Chase: A Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995) is the definitive treatment of the life of the man whose name was synonymous with antislavery principle in the Civil War era. Niven is a biographer and has described the lives of Gideon Welles, Martin Van Buren, and John C. Calhoun. His volume on Chase conforms to Albert Jay Nock's prescription for modern biography: "An objective account of the life of one man. It begins with his birth, ends with his death, Page [End Page 23] and includes every item of detail which has any actual or probable historical significance." [4]

Reading Niven's books is almost like actually being in the archives, more than 150 collections of which he consulted in the preparation of his volume. He provides a meticulous account of Chase's life and the politics of racial reform in which he was involved throughout his career. In order to place Niven's contribution in its proper historiographical perspective, I shall consider it in relation to the two earlier works that warrant the attention of Civil War historians: Albert Bushnell Hart's Salmon Portland Chase (1899) and Frederick J. Blue's Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1987).

I

The big picture into which the study of racial reformism fits concerns the abolition of slavery. How did an institution as old, established, legally protected, and universal as slavery, in its American variant of racially conditioned involuntary servitude, become uprooted and abolished in the relatively brief span of a single generation, from the 1830s to the 1860s? To know how and why such momentous change occurred might tell us something important about the nature of social change in the modern world. It might also tell us something important about American politics and the significance of reform movements in the American political tradition. If the elimination of slavery in the deepest sense can be attributed to the abolitionist movement, the fact would show the fundamental significance of reformism in American politics. If the end of slavery did not result from the agitation of racial reformism, the practical relevance of reformism as an instrument of social change might be open to question. The lives of many reformers have been chronicled in an attempt to answer these questions; they have also figured in writing about Chase as a racial reformer.

In many ways the most illuminating study of Chase's political career is Albert Bushnell Hart's late-nineteenth-century account. Through the circumstances of his family history Hart was close to the sources of the western wing of the abolitionist movement that Chase represented. Hart also had the advantage of writing when Page [End Page 24] the concept of statesmanship was still an accepted concept in historical scholarship and before the rise of progressive history made reformism the touchstone of political intelligence in the opinion of the intellectual classes. [5]

Accordingly, Hart, who was both a political scientist and historian, employed the concept of statesmanship as an analytical framework for his study. He presents Chase as a statesman whose life embodied many aspects of the national character.[6] Chase reflected the New England tradition of learning and statesmanship, a Western knowledge of the power of organization, and "a national insight into the meaning of the American system of government." [7]

The underlying idea in Chase's varied public service, in Hart's view, was to bring the law up to the moral standards of the country and make the law and moral standards apply to blacks as well as whites.[8] This was the mission of racial reformism as it would be conceived of by twentieth-century historians influenced by the civil rights movement. In Chase's case, dedication to the mission was complicated by the unusual, not to say excessive, ambition for political office and worldly fame that he manifested throughout his life. A key issue for students of Chase and racial reformism in general, therefore, is the relation of morality and politics.

The problem is that reformism as a concept of political action, unlike that of statesmanship, rests on an assumption of the moral superiority of the reformer. If it has always been difficult to justify the assumption that superior moral reasoning has been vouchsafed to a particular individual or group of persons, it is all the more so under the conditions of expanding democracy and proliferating cultural pluralism characteristic of modernity. Yet it was precisely this tendency of thought that affected—or perhaps afflicted—American politics in the antebellum period. William R. Brock has observed that at the time of the founding the purpose of government was to protect citizens' rights, and utility and expedience were the tests applied to government action. In the mid-nineteenth centu- Page [End Page 25] ry, however, the idea was revived that government had a moral character and that public policy should meet the standards set by conscience. In both North and South a disruptive force, which Brock refers to as "political conscience," transmitted the imperative of individual morality to the wider stage of national affairs. [9]

According to their own self-understanding, abolitionist reformers were the most moral of men. The obvious failure of their reform methods to change public opinion forced them to engage in partisan political action. [10] Like other partisans, however, the political means that abolitionists employed might be morally ambiguous and possibly even unscrupulous or unprincipled. Chase's historical significance, among other things, was to underscore the tension between reformist moralism and the political ethics required by ideological partisanship in an age of expanding democratic pluralism.

Chase evinced an attitude of supreme moral rectitude in combination with a driving political ambition that confused self-promotion with dedication to the cause of reform. From the moment he joined the abolitionists, Chase exhibited a "fascination" with coalition politics. Throughout the 1840s he displayed a "restless, programmatic quest" for antislavery union, working to advance his own interests along with those of the Liberty Party.[11] The question for historical analysis is whether Chase just happened to be unique in this political opportunism, or whether he signifies the emergence of a new political and social type characteristic of liberal pluralist society.

Chase's conversion to abolitionism was the first crisis in his political career that requires interpretation. Hart views his conversion as religious in nature, born of the belief that slavery was a moral evil. Although recognizing that as a result of his conversion Chase eventually obtained the worldly status for which he longed, Hart stresses the element of material self-sacrifice involved in his decision in 1841 to join the tiny and unpopular Liberty Party. Reluctantly following his convictions, Chase took up a cause that was "inexpressibly distasteful" to his professional associates and neighbors in Cincinnati. [12] Page [End Page 26]

As Hart conceives of it, Chase found his calling as an abolitionist lawyer defending fugitive slaves and an organizer for abolitionist political meetings. Hart observes that as a lawyer Chase depended on "luminous principles" rather than authorities; by the same token, as a political organizer he was a skilled and astute publicist who knew how to state great principles in popular form.[13] Years of tireless political organizing came to fruition in the formation of the Free Soil Party in 1848, in which no one, in Hart's view, played a more arduous or honorable role than Chase. Nor does Hart judge harshly the political bargain with the Democratic Party in Ohio, a bargain thought to be corrupt by his fellow abolitionists from whom he broke, by which Chase was elected U.S. senator. Hart accepts Chase's judgment that his action in no way compromised his political principles. Going beyond Hart's assessment, we might say that, according to Chase, parties were merely instrumental organizations, and fidelity to party—even a virtuous party of moral reformers—could be sacrificed in the name of principle.

Hart acknowledges, without exaggerating, the part played by the movement for racial reformism in the abolition of slavery. Political abolitionism, and Chase as the leading expositor of antislavery principles, had what can be described as a configurative and rationalizing role. The decisive actions that caused slavery to become a national political issue were those of the slave power in securing the annexation of Texas and provoking the Mexican War, not the moral suasion and political appeals of abolitionists. In a broader sense Hart holds that the emergence of abolitionist opinion was owing to the humanitarian progress that the northern states experienced between 1750 and 1825. In due course, abolitionism was produced by the same social developmental forces that led to more humane treatment of apprentices, indentured servants, debtors, prisoners, paupers, and insane persons.[14]

In its various political manifestations, abolitionism, and Chase as the chief publicist of the movement, rationalized the systematic attack on slavery required by humanitarian progress. Rather than assaulting slavery directly in the states where it existed, however, Chase would achieve the goal indirectly through the "denationalization" of slavery. The term referred to the divorce of the federal government from all contact whatsoever with the peculiar institution. To this end, Chase and the abolitionists were prepared, as in their opposition to the return of fugitive slaves and the extension Page [End Page 27] of slavery into the territories, to resist, repudiate, and ultimately abrogate the Union. On the other hand, they reserved the right on prudential grounds to defend the Union as a perpetual national government should the slaveholders seek to achieve the same end of divorcing the federal government from slavery by withdrawing their states from the Union.

The period of Chase's most constructive political work ended with the coming of the Civil War. In the deepest sense, the sectional conflict was never simply a matter of the morality of slavery as an institution, as racial reformers tended to define it. The issue was the nature and course of national development under what even the great nationalist Daniel Webster referred to as a "constitutional compact." [15] The compact was ambiguous, being in substantial respects both a contract between sovereign states in the nature of a confederation and the instrument of a sovereign national government. That one side believed slavery morally wrong and the other believed it a positive good was surely a basic difference. But this was not the only, nor arguably the most fundamental, difference in the sectional conflict. Slavery was the issue, among a number of conceivable issues, that occasioned the conflict over the course of national development and the nature of the union of the American states.

As these issues came to dominate American politics, racial reformers played a diminished role in resolving them. Chase in particular, according to Hart, performed two functions. He was secretary of the treasury under Lincoln, and he served as the leading representative and symbol of the racial reformist wing of the Republican Party. As treasury head, Chase presided over a financial and banking system that owed more to wartime exigency and political expediency than to the laissez-faire economic ideology that Chase had long professed. Although the economic soundness and rationality of Chase's banking and fiscal policies were subject to criticism, they sustained the war effort. In his partisan and ideological role as a racial reformer, Chase's actions were more questionable from the standpoint of statesmanship.

Although occupying one of the two most important positions in the cabinet, Chase distinguished himself, in Hart's words, "as a representative of discontent and protest against his president and chief." [16] Failing to show patriotic fidelity to Lincoln, Chase refused Page [End Page 28]

to subordinate himself to a man whom Chase believed inferior to himself in insight and understanding concerning issues raised by the war. Chase felt superior to Lincoln, according to Hart, because of Chase's experience and service in the cause of political abolitionism. In fact, the depth of Chase's political insight and the scope of his statesmanship were limited by what Hart describes as a lack of imagination and sense of proportion. [17] We might say these tendencies of mind reflected the limitations of Chase's reform mentality. Hart states that although possessing a "Roman-like aggressive virtue, a Cato-like consciousness of uprightness," Chase assumed that what was reasonable to him must appear reasonable to others. [18] Hart credits Chase with seeing more clearly than any other man, except Lincoln, the necessity and moral effect of sticking to consistent principle. But Chase was deficient in the virtue of prudence that guides the application of principle in the actions of the statesman. Hart expresses this judgment in concluding that Chase could never have been a father of his country. He was, rather, "one of those elder brethren who freely suggest, criticise, and complain, and who by the rectitude of their own lives ... influence the children as they grow up." [19]

II

Hart's book stands up well almost a century later, testimony to the validity of at least some works of scientific history. Recent scholarship on Chase fits into the interpretive framework of Hart's study, although it rejects the idea of statesmanship as an analytical concept. More strictly biographical in nature and based on more extensive research, the works of Frederick Blue and John Niven offer distinctive interpretations of Chase's activity as a reformer.

Blue's biography represented a delayed reaction to the influence of the civil rights movement on Civil War historiography. Suggesting that historians had placed too much emphasis on Chase's ambition for office, Blue intended a corrective portrait that called attention to Chase's advocacy of racial equality. He interprets Chase's legendary political ambition as subordinated to the lifelong goal of racial reform. According to Blue, Chase desired power not as an Page [End Page 31] end in itself or for his own gratification, but as a means to the end of securing civil rights for black Americans.[20]

Blue presents a psychological interpretation of Chase's conversion experience. He suggests that in becoming an antislavery activist Chase manifested a desire to become a father figure to those he felt he could help. The intended beneficiaries included Chase's wives (he married three times), daughters, brothers and sisters, young lawyers in his office, and especially fugitive slaves and free blacks. Chase, who was nine when his father died, may have been moved by a desire to provide the kind of assistance and guidance he had missed as a boy. In personality terms, this development signified the forsaking of ambition and self-aggrandizement and a commitment to improving the quality of life for others.[21]

In his rehabilitation of Chase, Blue looks sympathetically on his sometimes questionable actions as a political abolitionist. Blue accepts Chase's view that party unity, even or perhaps especially among moral reformers, was ultimately less important than promoting ideological goals. He concludes that when Chase broke ranks with fellow Ohio abolitionists and arranged the deal that secured his election to the Senate, he was acting out of principle rather than expediency. Chase's maneuver strengthened the antislavery cause and was consistent with his Democratic leanings on issues not related to slavery. Only in the eyes of critics did Chase abandon the principles of the Free Soil movement for the sake of personal advancement.[22]

It is difficult to put a good construction on Chase's incessant quest for the presidency, which began in the Republican Party in 1856 and ended somewhat abjectly in his attempt to win the Democratic nomination in 1868. Nevertheless, Blue revises the standard account by viewing Chase's pursuit of office in the context of nineteenth-century political culture. Blue considers unfounded the charge that Chase, as secretary of the treasury, built an anti-Lincoln patronage machine to promote his presidential prospects. Chase merely carried on a well-established practice of the political process and was not disloyal to Lincoln. [23] Page [End Page 32]

Few historians have had difficulty understanding why Chase never became president. The wonder is that he so long remained, in his own mind and in the eyes of at least some political strategists, "available." Chase's identification with abolitionism, however, made him "a towering figure of his times."[24] And Chase believed he should be president because, as a reformer, he had what Blue agrees was a fuller commitment to the cause of racial justice than Lincoln. Chase was willing to take political risks ahead of public opinion and in the face of overt political racism. [25] Of course Lincoln understood political possibilities better than Chase, as Blue acknowledges. But it is not to Blue's biographical purpose to consider whether Chase the reformer or Lincoln the statesman made the more significant contribution to racial reform. Giving Chase his due, Blue says that he failed in presidential politics because of his radicalism and inability to create an effective political organization.

In this light, Blue interprets Chase's attempt to win the Democratic presidential nomination in 1868. After Chase became chief justice of the Supreme Court, he acquired a more critical institutional perspective on congressional reconstruction policy. This tempered his partisanship and helped him conduct the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson in an objective and impartial manner. At that same time, Chase was calculating his chances of obtaining the Democratic nomination, a calculation that contributed to his performance during the impeachment trial. Blue nevertheless calls Chase's party switch yet another example of his commitment to principle. It was not, Blue pointedly concludes, the expedient act of a desperately ambitious and inept politician, as it might appear to be. In view of the differences that existed between him and the Republican Party, it was natural and consistent with his political philosophy for Chase to change to the Democratic Party.[26] Blue concludes that the "'real glory of his life' lay in his 'persevering agitation against slavery' and all forms of racial injustice." [27] Page [End Page 33]

III

The publication of John Niven's massive volume reflects his belief that the life of Chase is important enough to warrant a more complete and accurate account. Niven says his intention is to go beyond politics and consider Chase's family life and the social environment in which he acted. He characterizes Chase as "preeminently a representative nineteenth-century man." [28] If Chase was a typical man of his time, however, the times were not as distinct and remote from twentieth-century American society as the use of this historical cliché might imply.

Commenting on the revival of scholarly interest in Lincoln's secretary of the treasury, Don E. Fehrenbacher has observed that Chase's life reflects two dimensions of nineteenth-century American civilization: social reform and individual promotion.[29] The key to Niven's interpretation of Chase is to see these two dimensions not as separate and distinctive motives in conflict with each other, but as parts of a substantially and for the most part integrated personality. I do not suggest that Niven himself in the formal terms of psychological theory advances this interpretation. His book proceeds without benefit of formal theory, but if there is any hypothesis it is that Chase had a kind of split personality. Niven refers to a dark side of Chase's personality, seen in his driving ambition, and a light side, seen in his dedication to humanitarian reform.[30] Nevertheless, the evidence presented in Niven's account shows less an anxiety-producing struggle between these two tendencies or motives than a functional integration and balance that blurred the distinction between social reform and self-aggrandizement.

Niven's rich and textured narrative makes clear that the purpose of racial reform in Chase's life was to satisfy his ambition for social distinction and worldly success. Disposed by his New England heritage to improve the world, Chase pursued a career in political abolitionism and racial reform. Niven's account shows that he did so very much in the manner of a twentieth-century careerist: He sought professional advancement by all possible means. To use terms of contemporary social science, Chase illustrates what might Page [End Page 34] be seen as the political commodification and secularization of the moral virtue claimed by nineteenth-century humanitarian reformism. Chase's notorious pomposity notwithstanding, his careerism anticipates the phenomenon of the reformer-celebrity that has become a familiar feature of political culture in twentieth-century America.

As for Chase's conversion experience, Niven states that the "lofty motives" that led Chase to seek "the freedom and equality of all mankind ... masked a thirst for office and power that was deeply ingrained in his character." [31] Niven says Chase's personality was formed in a troubled childhood and adolescence when, after the death of his father, he lived with his uncle, Philander Chase, the Episcopal bishop of Ohio. The bishop was a domineering man who imparted in his nephew the trait of "insistence on success at whatever price." [32] Niven sees this as a flaw in Chase's character, but it seems not to have been a disabling or dysfunctional one. In fact, Chase grew to become a confident, self-assured, nonintrospective man whose personality proved an apt vehicle for advancement.

The elements of Chase's personality were integrated and fused in the first political crisis of his life, the decision to become a political abolitionist. Defeated in his bid for reelection as a Whig to the Cincinnati city council, Chase had nowhere to go politically except into the Liberty Party. In this new political association and in his activity as a lawyer defending fugitive slaves, Chase "blended personal advantage with what he presumed to be the greater good."[33] The decision to join the Liberty Party, a feeble and socially undesirable organization, was painful. But Niven says the move held out unique possibilities for Chase personally. Similarly, as a lawyer for fugitive slaves, Chase, blessed with "an innate sense of public relations," courted unfavorable judicial decisions because "he sensed the political undercurrent that made states' rights and slavery issues that would eventually redound to his own advantage." In general, Niven concludes, Chase's "commitment to humanitarian causes balanced his drivingly ambitious nature." [34]

Niven's account is laced with a candor about the nature of Chase's reform mentality that may strike some readers as somewhat harsh. His interpretation differs sharply from Blue's. Niven Page [End Page 35] writes that all of Chase's activities in church, education, and community affairs "were aimed at his own advancement politically, which he invariably rationalized as contributing to the benefit of humanity and the glory of God."[35] In fugitive slave cases, Niven says, Chase's main concern was not the fate of the defendants, but the promotion of the cause of political abolition. In the famous Van Zandt case, which brought him much acclaim, "Chase's emotional appeal to natural right was made strictly for its value as publicity for him and for the Liberty party." [36] An "inborn publicist" with a keen awareness of the power of the press, Chase saw a particular political role for himself in devising a rhetorical strategy by which the Liberty Party could purge itself of its abolitionist label. This was the point of Chase's constitutional argument for divorcing the federal government from all contact with slavery. It was designed to promote abolitionism, but under what some racial reformers considered a false premise that lessened the commitment to the ultimate goals of the movement.[37]

In many ways the high point of Chase's career, from the standpoint of personal and professional satisfaction, came in 1848 with his success as an organizer of the Free Soil Party. Niven observes that younger men were now "attracted to Chase not because of any personal warmth that he projected but because of his earnestness, political ability, and sincerity, so they thought, in his zeal for the antislavery cause." [38] Supremely confident, associating his personal fortunes with the advancement of the cause, Chase proceeded to arrange his election to the Senate. He effected the deal with the Democratic Party in Ohio that more than anything else contributed to the growing belief—which Niven seems to think had foundation—that Chase "would sacrifice virtually any position he had staked out in the past for his political advantage." [39] A few years later, during the controversy over the Nebraska Act, Chase wrote the sensational propaganda tract titled "Appeal of the Independent Democrats." His attack on Stephen A. Douglas helped to precipitate the political realignment that led to the formation of the Republican Party. The experience confirmed Chase's ability and reputation as a radical agitator and fixed all the more firmly his determination to seek continually "some issue that would identi- Page [End Page 36] fy him with man's inhumanity to man and thus solidify further his place in progressive politics." [40]

In the fundamentally altered conditions of Civil War politics, when the slavery issue was subordinated to the demands of state-building, Chase the careerist-reformer proved to be an ineffectual politician. His accomplishments as an antislavery agitator and organizer gave him high visibility and standing in the radical wing of the Republican Party. In Niven's view, Lincoln brought Chase into the cabinet not only because he had a sure grasp of the issues facing the Union but also, and perhaps more importantly, because Chase was, in words Lincoln was alleged later to have used to describe him, a "big man." [41] Exactly what Lincoln might have meant in referring to Chase in these terms is not clear, but a big man is different from a great man. Niven sees Chase as a big man in the sense that he had the stature, self-confidence, and "majestic port" that made for the kind of strength that Lincoln thought his administration needed.[42]

Chase also had big ideas in a constitutional sense, expressed in what Niven describes as his "passion for assuming the chief executive role." [43] Chase was Lincoln's chief unofficial advisor on military affairs. Acting as a kind of co-president, Chase throughout 1862 lobbied Congress and maneuvered "to achieve a position of control in the cabinet and with that the control of a 'weak' President."[44] This project came to a head in the cabinet reconstruction crisis in December 1862, which ended in Chase's humiliation, at Lincoln's hands, in the presence of the Republican senators with whom Chase had consulted. The outcome foreclosed the attempt to create a plural executive that was implicit in Chase's actions.[45] Page [End Page 37]

Niven says the cabinet reconstruction fiasco marked the start of Chase's political decline. A "desperate attempt to achieve great purposes" led Chase to forsake loyalty to Lincoln, his chief.[46] Niven suggests that the cause of Chase's conduct lay either in the treatment he received from his uncle as a child or the "acute frustration of an essentially tidy administrative mind."[47] Neither explanation is persuasive. The point rather would seem to be that Chase, with his careerist-reformer mentality, was now out of his element. In the antebellum period the two sides of his personality—self-seeking ambition and moral reform—functioned effectively to the end of disrupting the existing political establishment. In the entirely different context of war and reconstruction, the agenda of state-making and nation-building imposed demands for prudential statesmanship that revealed the limitations of "one-idea" reformism, even in the broader form that racial reform assumed in the Republican Party. [48] Chase the careerist-reformer was no match for Lincoln the statesman.

Through the rest of the war Chase persisted with his causes. Sensing the growing popularity of reconstruction as he had once forecast the appeal of antislavery, he promoted Negro suffrage as the panacea for postwar political and postemancipation social problems.[49] And he continued in his request for the presidency, allowing his name to be used by the dissident politicians led by Sen. Samuel C. Pomeroy, who challenged Lincoln's renomination in 1864. Imprudent and unstatesmanlike as Chase's political maneuvering was, it nevertheless says something about his stature as a careerist-reformer that after leaving the cabinet, and after failing to win nomination for the congressional seat from Ohio, his only option for remaining in public life was to get appointed to the Supreme Court.[50] Not a bad way to close out one's career, all things considered.

Attending to Chase's social milieu more than previous writers, Niven shows that Chase's career-reformism paid off handsomely in the worldly terms that meant so much to him. While acknowl- Page [End Page 38] edging "a bedrock of moral substance" in his character, Niven says that Chase "was curiously blind to the lifestyle of the rich" to which he grew accustomed.[51] He took for granted the comfort, the servants, even the gaudy splendor of his successful friends, family, and associates.[52] For the new type of careerist-reformism that Chase represented, virtue was not its own reward.

Yet Chase did not accept with serenity the role of judicial statesman that ironically befell him in his final years. His heart was not always in his work. In 1866, for example, he let it be known that he would consider becoming president of the Union Pacific Railroad if offered the job. He preferred an active business life to the "monotonous labors and dull dignity of my judicial position." In 1869 Chase proposed to his banker friend Jay Cooke that Cooke appoint him president of the Northern Pacific Railroad. "My antecedents and reputation would justify a good salary," Chase observed. Although Cooke declined the offer, he loaned Chase $22,000 for the purchase of an estate and continued to see to Chase's financial needs.[53] Among the last things Chase did as chief justice was to lobby Congress for a pay increase that would almost double the salary of Supreme Court justices.

Chase's historical significance lies in his reformism and his notorious political ambition. Better than any previous work, Niven's candid account shows the organic relationship between these two motives in the life of a new political type, the careerist-reformer.

How to control ambition has been a problem for political theory and moral philosophy since antiquity. In the modern world generally, and in the liberal political society of the United States in particular, ambitious reformism raised new questions about the ethic of responsible political action. In the Lyceum Address Lincoln warned against a man of ambition who in his thirst for distinction might emancipate slaves or enslave freemen. [54] The problem that concerned him was not the slavery issue itself, nor the sectional conflict over slavery. Lincoln was concerned rather with the maintenance of limited constitutional government in a democratic republic. Precisely what policies and action were required to fulfill this end in the antebellum period were controversial, in large Page [End Page 39] part because the requirements and intent of the Constitution with respect to the nature of the Union were unclear.

There was nothing unclear, however, about the abolitionist commitment to racial injustice as the highest end of political action. Within this ideological framework, Chase's dedication to the cause of racial reform challenged the existing regime as a morally corrupt, slave-holding republic. His actions won him fame and political success as an antislavery agitator and strategist, marking the high point in his political career. His subsequent public service suggests the emergence of careerist-reformism as a new political type, one of the ways, perhaps, in which liberal, pluralist society assimilates the revolutionary tendency inherent in the reformist mentality. Page [End Page 40]

Notes

-

The belief of many historians that the issue

of racial justice forms a direct connection between the Civil War

era and the modern civil rights era has been remarked upon by

Merton L. Dillon. Noting the participation of a number of Civil War

and Reconstruction scholars in the Selma, Alabama, civil rights

protest march in 1965, Dillon observed, "In this manner men whose

careers focused on the study of past crises concerning race

announced their intention to plunge into what many then regarded as

the very eye of the twentieth century's racial storm." Merton L.

Dillon, The Abolitionists: The Growth of a Dissenting

Minority (New York: W. W. Norton, 1979), vii. The involvement

of historians in contemporary civil rights struggles has continued

in recent years. See, for example, the Brief Amicus Curiae

of Eric Foner, John Hope Franklin, Louis R. Harlan, Stanley N.

Katz, Leon F. Litwack, C. Vann Woodward, and Mary Frances Berry in

the case of Brenda Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, Supreme

Court of the United States, October term 1987.

-

Lincoln has been viewed as a revolutionary by

writers as diverse as Dwight Anderson, Abraham Lincoln: The

Quest for Immortality (New York: Knopf, 1982); M. E. Bradford,

"The Lincoln Legacy: A Long View," Modern Age 24 (Fall 1980):

355–63; and James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the

Second American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press,

1991).

-

Harry V. Jaffa, Crisis of the House

Divided: An Interpretation of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates (New

York: Doubleday, 1959), 236–72.

-

Albert Jay Nock, in The State of the Union:

Essays in Social Criticism, ed. Charles H. Hamilton

(Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1991), 5.

-

The concept of statesmanship, drawn from

classical political philosophy, refers to wise action for the

public good based on knowledge of what ought to be done in a given

set of circumstances. The type of knowledge on which the actions of

the statesman depend is prudence or practical reason, as

distinguished from philosophic wisdom or theoretical knowledge. A.

D. Lindsay, ed., The Politics of Aristotle; or, A Treatise on

Government (London: Dent, 1912), viii–ix.

-

Hart's book appeared as a volume in the

American Statesmen series, edited by John T. Morse, Jr.

-

Hart, Salmon Portland Chase, 1.

-

Ibid., 435.

-

William R. Brock, Parties and Political

Conscience: American Dilemmas, 1840–1850 (Millwood, N.Y.:

Kraus, 1979), 68–69.

-

Richard H. Sewell, Ballots for Freedom:

Antislavery Politics in the United States, 1837–1860 (New

York: Norton, 1979), 1–79.

-

Sewell, Ballots for Freedom, 204.

-

Hart, Salmon Portland Chase, 52, 90.

-

Ibid., 148.

-

Ibid., 120.

-

Speech of Daniel Webster in Reply to Mr.

Hayne of South Carolina (Washington, 1830), 16.

-

Hart, Salmon Portland Chase, 432.

-

Ibid., 430–31.

-

Ibid. 423, 148.

-

Ibid., 435.

-

Frederick J. Blue, Salmon P. Chase: A

Life in Politics (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1987),

x–xii.

-

Blue, Salmon P. Chase, 35, 40. Blue

explored this subject further in "From Right to Left: The Political

Conversion of Salmon P. Chase," Northern Kentucky Law Review

21 (1993): 1–22.

-

Blue, Salmon P. Chase, 70, 73.

-

Ibid., 142, 214.

-

Michael Les Benedict, "Salmon P. Chase as

Jurist and Politician: Comment on G. Edward White, 'Reconstructing

Chase's Jurisprudence,'" Northern Kentucky Law Review 21

(1991): 150.

-

Blue, Salmon P. Chase, 206.

-

Ibid., 285.

-

Ibid., 323. The material that Blue quotes is

from Robert Warden, An Account of the Private Life and Public

Services of Salmon Portland Chase (Cincinnati, 1874), 816.

-

John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A

Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), vii.

-

Don E. Fehrenbacher, "Comment," Journal

of the Abraham Lincoln Association 12 (1991): 18.

-

Niven, Salmon P. Chase, 190.

-

Ibid., 5.

-

Ibid., 130.

-

Ibid., 63.

-

Ibid., 37, 55–56.

-

Ibid., 74.

-

Ibid., 81.

-

Ibid., 88.

-

Ibid., 113.

-

Ibid., 146.

-

Ibid., 153.

-

At the time he appointed him chief justice,

Lincoln reportedly said, "Chase is about one and a half times

bigger than any other man I ever knew." Blue, Salmon P. Chase,

x, citing Hart, Salmon Portland Chase, 435. Niven does

not use this material, and it does not appear in Charles Fairman's

exhaustive account of Chase's nomination to the Supreme Court in

Reconstruction and Reunion, 1864–88 (New York:

Macmillan, 1971), part 1.

-

Niven, Salmon P. Chase, 226. I do not

find explicit reiteration of the point Niven made in an earlier

essay, that Chase's attributes made him the right person to deal

with the rich, self-assured leaders of the eastern banking

community. In his book there is plenty of evidence, however,

describing Chase's interactions with the banking community in this

light. Ibid., 264–67. Compare Niven, "Lincoln and Chase: A

Reappraisal," Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 12

(1991): 1.

-

Niven, "Lincoln and Chase," 3.

-

Ibid., 309.

-

Phillip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of

Abraham Lincoln (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1994),

184–75.

-

Niven, "Lincoln and Chase," 313.

-

Ibid.

-

Concerning the agenda of state-making, see

Stephen Skowronek, The Politics Presidents Make: Leadership from

John Adams to George Bush (Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

1993), 197–227, and Richard F. Bensel, Yankee Leviathan:

The Origins of Central State Authority in America,

1859–1877 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

-

Niven, "Lincoln and Chase," 317, 320.

-

Ibid., 371, 373.

-

Ibid., 399.

-

Ibid., 441.

-

Blue, Salmon P. Chase, 311–12.

-

Roy P. Basler, ed., Marion Dolores Pratt and

Lloyd A. Dunlap, asst. eds., The Collected Works of Abraham

Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press,

1953–55), 1:114.