The Social Bases of Democracy Revisited; or, Why Democracy Cannot Be Dropped in Bombs from B52s at 30,000 Feet

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract: The contributions to Sociological Amnesia (Law and Lybeck, 2015), show how the discipline of sociology has a well-developed capacity to forget earlier sociologists and – more importantly – their valuable ideas and findings. So it is not entirely surprising if high-level public officials, few of whom are sociologists, remain in still greater ignorance. The case in point here is the rich body of theory, findings and debate on the question of the social foundations of political democracy. This body of literature can be traced back at least to Alexis de Tocqueville, but research in the field was especially vigorous in the quarter-century after the Second World War, having been stimulated by need to understand the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Nazism, as well as similar movements elsewhere. The literature was especially well synthesised in William Kornhauser’s The Politics of Mass Society (1959). In this paper, I revisit Kornhauser’s book, and ask whether, if the earlier understanding of the social bases of democracy had not been forgotten (or wilfully dismissed), American foreign policy disasters – notably the invasion of Iraq – might not have happened.[1]

Keywords: Democracy; International Relations, William Kornhauser; sociological amnesia

Alex Law and Eric Royal Lybeck have edited a valuable book entitled Sociological Amnesia (2015), showing how the discipline of sociology has a well-developed capacity to forget earlier sociologists and – more importantly – their valuable ideas and findings. Although their book discusses only about a dozen, mainly European, major sociological figures who are now little known to students, nor indeed to a younger generation of professional sociologists, I suspect their sample is sufficient to lend support to a personal hunch that I have formed over a career that has now lasted for half a century. My hunch is that sociologists spend too much time reinventing the wheel, and inventing new terms for wheels that look ever more impressive and abstract, but fundamentally still mean ‘a wheel’. While empirical research methods have steadily advanced, my perception is that sociological theory – by which I mean broadly our overall understanding of how human society works – moves in a cyclical rather than accumulative fashion.

But I don’t want to be inward looking. Sociologists do not seek just to understand human society for themselves, but to improve the human means of orientation – to improve how people at large understand the society in which we live.

If social scientists are so prone to amnesia, it is not entirely surprising if high-level public officials, few of whom are sociologists, remain in still greater ignorance of useful sociological ideas. And their ignorance can have far greater consequences than the mere forgetfulness of sociologists themselves.

The social foundations of democracy revisited

The case I want to discuss is the rich body of theory, findings and debate on the question of the social foundations of political democracy. I want to suggest that the amnesia concerning this body of literature has had catastrophic and worldwide consequences, up to and including the invasion of Iraq, the destabilisation of Libya, the proxy wars now being fought in Syria – and, in fact, to pretty well the whole of American foreign policy since the Second World War (although that is too big a claim to be fully explored in this paper).

The modern empirical–theoretical investigation of the social foundations of democracy can be traced back at least to Alexis de Tocqueville’s great work Democracy in America (1961 [1835–40]). Tocqueville perceived that the strength of the American political system stemmed only in part from the Constitution and its consciously sophisticated allocation of rights and responsibilities between the federal and state authorities and its separation of executive, legislative and judicial powers. More important for American society, he saw, was the tradition that had developed in an altogether unconscious and unplanned way, of local self-government and of groups combining together in associations to pursue their common interests. The way in which political feelings were mobilised and channelled he perceived to be particularly important; for individuals would be powerless against the forces of the centralised state unless they could combine with others to represent their interests and secure their rights. Such associations would replace the countervailing power which aristocracy, so Tocqueville thought, had exercised against the state in feudal times. Minority rights under majority rule could not be guaranteed by the simple formula that related each citizen to a single vote. Democracy, in other words, was not the same thing as majoritarianism, a point that seems to have been lost in the course of recent early twentieth-century events such as the 2016 referendum in Britain, very narrowly won by the advocates of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union.

These quite complex and balanced arguments of Tocqueville’s have often been lost sight of. Americans have always tended to read Democracy in America as a paean of praise for their own country, and to read mainly the discussion of democratic politics in the first volume. But Tocqueville always saw two sides of the coin: he famously spoke of ‘the tyranny of the majority’, both in politics and (in the second volume) also in cultural life.[2]

Many other subsequent sociologists contributed to our understanding of the social bases of democracy. Perhaps especially worth mentioning is Georg Simmel’s (1955) idea of ‘the web of group affiliations’, which was used by Lewis Coser as the basis of his book The Functions of Social Conflict (1956) – both of them showing how people’s web of cross-cutting social affiliations served to mitigate the intensity of social conflicts and thus to contribute to stable democratic politics.

But research in the field was especially vigorous in the quarter-century after the Second World War, having been stimulated by the need to understand the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Nazism, as well as similar movements elsewhere. This can be seen clearly in a book that every student of political sociology read from the 1960s until (I would guess) the 1980s, Seymour Martin Lipset’s Political Man (1956). The book contains classic essays on ‘“Fascism” – Left, Right and Centre’ (pp. 131–76) and ‘Working-class authoritarianism’ (pp. 97–130), both highly relevant to the ‘populist’ movements that have arisen in recent years in both Europe and America, and both making plain that authoritarian tendencies can be found in all classes within industrial societies. Another concern in the 1950s and the 1960s was with the prospects for the development of democratic politics in the newly independent countries of post-colonial Africa and elsewhere. Reflecting the general thinking of the time, and influenced for example by the influential study by the political scientist David Apter (1955) about Ghana on the brink of its independence from Britain, Lipset stressed the importance of economic factors in the genesis of democratic politics:

The general income level of a nation also affects its receptivity to democratic norms. If there is enough wealth in the country so that it does not make too much difference whether some redistribution takes place, it is easier to accept the idea that it does not greatly matter who is in power. But if loss of office means serious losses for major power groups, they will seek to retain or secure office by any means available. A certain amount of national wealth is likewise necessary to ensure a competent civil service. The poorer the country, the greater the emphasis on nepotism – support of kin and friends. And this in turn reduces the opportunity to develop the efficient bureaucracy which a modern democratic state requires. (Lipset, 1960: 66)

There is much in this remark that looks prescient even in hindsight, but the history of most of Africa in the decades since it was written is enough to show that ‘general income level’ is not enough in itself, and that the forces of nepotism – ‘corruption’ in Western perceptions – are enough to impoverish a country. More strikingly, the idea that ‘if there is enough wealth in the country, so that it does not make too much difference whether some redistribution takes place, it is easier to accept the idea that it does not greatly matter who is in power’ looks distinctly questionable even in extremely wealthy countries at the present day. In the USA in particular, even though the lion’s share of increasing GNP has gone to the mega-rich, most of them seem to think that it does indeed matter who is in power; and ‘populist’ movements for which it is tempting to revive Friedrich Engels’s notion of ‘false consciousness’ have been cultivated to minimise the chances of ‘some redistribution’.[3]

I would, however, argue that rather than Lipset’s famous book, the research literature on the social bases of democracy was best synthesised in William Kornhauser’s The Politics of Mass Society (1959). In this paper, I shall revisit Kornhauser’s book, and ask whether, if the earlier understanding of the social bases of democracy had not been forgotten (or wilfully dismissed) in high places, American foreign policy disasters – notably the invasion of Iraq – might not have happened.

Kornhauser’s argument

By ‘mass society’ in the title of his book, Kornhauser does not mean simply large-scale and complex society. Nor does it refer to ‘the masses’ in the sense of the lower social classes. Most important, it is certainly not the same as pluralist democracy. Rather, by ‘mass society’, Kornhauser means one in which there are ‘large numbers of people who are not integrated into any broad social groupings, including classes’ (1959: 14). Furthermore:

A central aim of this study is to distinguish between mass tendencies and pluralist tendencies in modern society, and to show how social pluralism, but not mass conditions, supports liberal democracy. (1959: 13)

In the history of social and political thought, Kornhauser traces two seemingly opposite strands of criticism of mass society in his sense of the term.

The first, he calls the ‘aristocratic’ tradition of thought. Its exponents criticise mass society on grounds of its undermining the exclusiveness of elites. They may deplore it on either political or cultural grounds, or both. Kornhauser includes in this tradition such writers as Jacob Burckhardt, Gustave Le Bon, José Ortega y Gasset, and Karl Mannheim; he also includes Tocqueville, though as I have already argued he can be enlisted on both sides of the argument. For our purposes, the most important political point is that mass society results in a loss of authority and policy-making autonomy on the part of institutional elites.

High access to elites results from such procedures as direct popular elections and the shared expectation that public opinion is sovereign. When elites are easily accessible, the masses pressure them to conform to the transitory general will. (1959: 28)

The second tradition in criticism of mass society is the ‘democratic’ one. According to it, the risk to democracy, the risk of tyranny, is associated with the atomisation of the mass of the people by the breakdown of the web of group affiliations among the people at large. This makes them vulnerable to manipulation by elites in their behaviour and their thinking. Karl Marx foresaw this possibility in his discussion of the rise to power of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the Emperor Napoleon III. Referring to his populist manipulation of the French peasantry, Marx famously remarked that the peasants ‘formed a class much as potatoes in a sack form a sack of potatoes’ (Marx, 1968 [1852]: 97–180); they lacked the means of communication and collective organisation to resist manipulation.

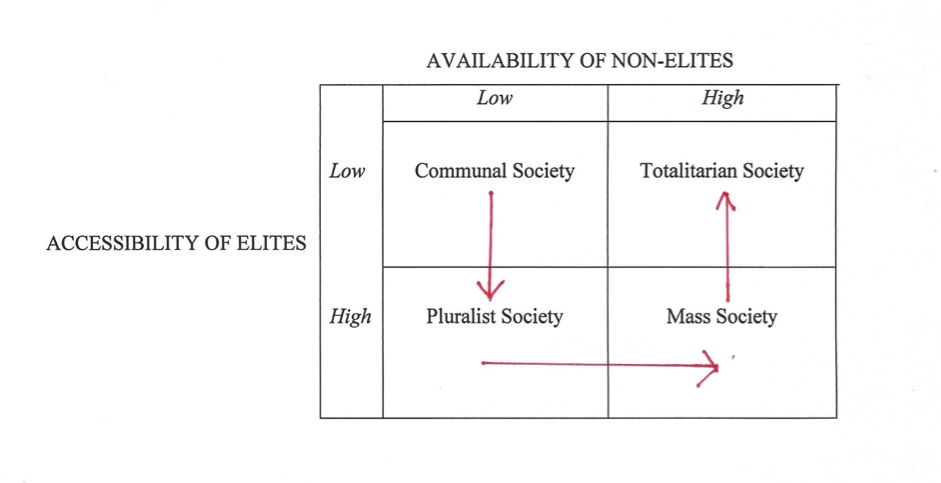

Kornhauser’s argument is that both the aristocratic criticism and the democratic criticism of mass society have some validity, but that stable pluralist democracy requires a balance. On the one hand there is a need for a measure both of ‘autonomy’ and ‘accessibility’ on the part of elites. And, on the other hand, non-elites must have both some capacity to make their wishes felt and the means of resisting manipulation by elites. It leads Kornhauser to construct this four-box diagram:

Kornhauser also implies a sort of developmental model, though he does not overstate it. The main transition with which he is concerned is the danger of pluralist society decaying into a mass society, with the further possibility that a mass society will decay into a totalitarian one. The trajectory is indicated by the arrows in the diagram

Note that the first arrow points from the pre-modern ‘Communal Society’, in which elites and masses have little interaction, to ‘Pluralist Society’, in which ‘accessibility’ and ‘availability’ are neatly balanced. All the historical evidence is that this process is a long-term and slow one, in which the necessary dense web of social interdependencies is woven only gradually. In particular it often depends on an adventitious outcome to internal struggles that eventuate in a relatively even balance between major power blocs. Just how adventitious this may be is illustrated by the very different outcomes of the same civil wars in the seventeenth century on the neighbouring islands of Great Britain and Ireland.[4]

On the other hand, the whole post-war literature on the social foundations of democracy grew out of a preoccupation with how authoritarian regimes had emerged in Europe between the wars, and in particular with the collapse of the Weimar Republic and Hitler’s rise to power in Germany. The preoccupation both of social scientists and especially of Western governments in the quarter-century since the collapse of the USSR has been the opposite: how can a transition take place from an authoritarian regime to a more democratic pluralist regime? The countries of the former Soviet bloc in Eastern Europe have managed this transition rather well, on the whole, although recent trends back towards authoritarianism in Poland and Hungary show that it is not entirely unproblematic. But here I am more concerned with the far less effective efforts made by Western governments to destroy (somewhat selectively) authoritarian regimes, especially in the Greater Middle East, and to replace them with functioning democracies.

The sociological question is whether – given that very many social processes are reversible – the developmental trajectory implied by Kornhauser can also be made to operate in the opposite direction. Not easily, not quickly, and only in the course of fairly slow long-term processes, I would suggest. The reason for this answer becomes clearer if we look at the main dangers to which Kornhauser pointed as precipitating transitions from pluralist to mass and possibly to totalitarian society.

The dangerous discontinuities

Three sources of political vulnerability in democracies were what Kornhauser called discontinuities in authority, in community and in society. Each of them contributed to the rise of mass movements that could subvert the pluralist order (Kornhauser, 1959: 119–74).

Discontinuities in Authority

Under this heading, Kornhauser summarises his evidence in the proposition that ‘if popular rule is introduced suddenly in a society previously subject to autocratic rule (i.e., without a constitutional heritage), it is likely to engender mass movements which may subvert it’ (1959: 173). A classic example is the subversion of the Weimar Republic, in part by old elites shaken by the abolition of the Hohenzollern regime (see, notably, Elias, 2013, especially pp. 186–222).

Discontinuities in Community

Under this heading, Kornhauser discusses urbanisation and migration. Although the degree of urbanisation is not correlated with vulnerability to destabilisation of pluralist democracy, the rate of urbanisation is.

if urbanisation proceeds at a very rapid rate, especially in its early stages it is likely to involve the uprooting of large numbers of people and the failure of new forms of associations to emerge. (1959: 173)

This is especially topical, given the scale of mass migration today, especially into Europe from the destabilised Greater Middle East. It should be noted that not only can rapid in-migration disrupt bonds of community,[5] but that rapid out-migration can have much the same effect in regions that are losing population. At the time Kornhauser was writing, a familiar example was the Poujadist movement in rural France in the 1950s.

Discontinuities in Society

Under this heading, Kornhauser makes a similar point about the effects of rapid industrialisation:

Industrialisation of the labour force tends to be highly atomising where industry is confined to large cities and large factories, where workers are recruited directly from the rural population, and where there is little prior development of workingmen’s organisations and severe repression of new unions. (1959: 174)

This may still be relevant in many parts of what used to be called ‘the developing world’. But note that it is also relevant to a situation that Kornhauser could not anticipate: the de-industrialising economies of today’s Western world, notably the USA and UK. Among the social bonds that were once considered essential to democratic politics were those provided by trade unions, key organisations in achieving a relative balance between elite and mass interests. It was striking, for example, that in the 2016 ‘Brexit’ referendum large majorities for British withdrawal from the EU were counted in regions such as the North of England, where old industries have collapsed and the old trade union solidarities dissolved, while London with its booming financial services sector was solidly for remaining. (The same contrast could be seen in the 2016 US Presidential election, between the prosperous east and west coasts and the ‘rust bucket’ states that gave Trump his Electoral College majority.) It is worth noting that a principal component of the neo-liberal ideology that now dominates the world is the destruction of union power.[6] Economic theorists justify this as promoting ‘efficiency’ and as enhancing profits – which are then supposed to benefit everyone by a ‘trickle down’ effect whose existence is doubtful. Narrowly economic theories would, of course, pay no attention to nebulous issues like stable democracy – a point to which I shall return in a moment.

Some conclusions

The conclusions that can be drawn from this discussion are of two kinds: conclusions about the real world of politics and global power; and conclusions about the discipline of sociology, its relative autonomy from, and its influence (or lack of it) over, policy makers ‘out there’.

Under the first heading, the conclusions are rather obvious.

1. Although social scientists have long recognised that the gradual monopolisation of the legitimate use of the means of violence plays a central part in state-formation processes, the growth of the ‘web of group affiliations’ and the ‘parliamentarisation of conflict’ are also essential and slow-growing elements in laying the social foundations of democracy. It is in the highest degree unlikely that a country such as Afghanistan, which is closer to the ‘Communal’ pole in Kornhauser’s model than any other, can be bombed into becoming a pluralist democracy. Afghanistan has experienced decades of foreign interference, by both the Russians and Americans, cumulatively destroying whatever stability once existed there – stability understood as a basic level of safety in people’s lives in the local communities of which a Communal society is composed.

2. But it is equally implausible that a country like Iraq, which used to be one of the most complex and economically thriving countries in the Greater Middle East – albeit an authoritarian, even totalitarian one – can be bludgeoned into pluralism by external military intervention. Quite the contrary: the American invasion has destroyed precisely the features that in Kornhauser’s model are the basis of a pluralist society. The same mistake was made in the overthrow of Colonel Gaddafi in Libya in 2011.

But what of the second set of conclusions, about what all this implies about sociology as a discipline? Here, things are more complicated.

3. We seem to have discovered a whole new instance of ‘sociological amnesia’ – in this case, not just forgetting about a particular writer but about a whole body of thinking and research.

4. This points in turn to the inadequacy of what I have called our discipline’s ‘relative autonomy’. That is to say, too often we seem to allow the preoccupations of the powerful to dictate what we study. That is not surprising, because in many countries – even the most ‘Western pluralist democracies’ – governments and corporations are ever more openly seeking the major say in the direction of social scientific research. But, more specifically, I am thinking of the way in which, after the collapse of the Soviet bloc – and even though most of us ridiculed Francis Fukuyama’s notion of ‘the end of history’ (Fukuyama, 1989, 1992) – social scientists allowed the focus of their attention (and their funding) to shift towards studies of the ‘transitional’ societies, with its implicit assumption that Western-style ‘democracy’ was a sort of natural, automatic, inevitable end state of social development – the default setting of human society.

5. Even supposing that many sociologists did not accept this, it is sad to contrast the influence the impact of sociologists on global political thinking with that of economists. Only since the financial collapse starting in 2007–8 have many voices been raised against the dominant ideology of neo-liberalism – a ‘total ideology’ in Mannheim’s terms (1960 [1936]: 57–62) – but its economist spokesmen still shout much louder. They have produced a system of thought that justifies the unfettered pursuit of self-interest at the expense of broader values. As my teacher Talcott Parsons used to remark, no society can afford to have economic rationality as its highest value, because it will erode and undermine all other values.

6. It is true that in the post-war period some sociologists (like Lipset, mentioned earlier) placed great emphasis on the contribution that economic growth would make to the formation of pluralist democracies in what they called ‘the developing world’, they did not lose sight of the broader social picture. And economists in particular seem bent on developing very simplified models – based on what can be most easily quantified. I was recently talking to a distinguished economist-cum-economic historian who has produced a series of articles purporting to demonstrate that measures of liberalisation by autocratic regimes provided them with a safeguard against their revolutionary overthrow (Aidt and Jensen, 2014; Aidt and Franck, 2015). I pointed out to him that there was an older hypothesis – stemming from Tocqueville’s L’Ancien Régime et la Revolution (1955) and continuing through to the famous ‘J-curve’ hypothesis of James C. Davis (1962) – which suggested that measures of liberalisation acted to precipitate revolutions, on account of fuelling an explosive growth of expectations that could not be fulfilled. The economist was unaware of this line of thought.

By way of general conclusions, let us return to the Kornhauser model. It is worth noting how far some at least of Western democracies have strayed from Kornhauser’s ideal-type of ‘Pluralist Society’. Many countries in Western Europe – not to mention the USA – are witnessing the rise of insurgent mass movements, both of the left and the right. This is often attributed to the astonishing growth of economic inequality. But a more adequate picture is surely that they have become much closer to the model of ‘Mass Society’ in Kornhauser’s sense. Inequality is certainly part of that, but it makes better sense to see it also in the context of an increase in the availability of non-elites and accessibility of elites. That is to say, non-elites have increasingly been atomised, uprooted from traditional associations and loyalties, and thus more easily manipulated by media that have been concentrated in fewer, powerful hands. It was sometimes argued that the rise of the ‘social media’ – Facebook, Twitter and the rest – would provide the means of offsetting the concentration of ownership and influence in the traditional media. In fact, it appears that the new media largely reflect the prevailing divisions of opinion, but also amplify and vulgarise them. And the resulting volatility of public opinion has left elites too little autonomy from, and too much vulnerability to, the gusts of public opinion.

Of course, I am not arguing that if Western elites had read and understood the old literature on the social bases of liberal democracy, or if they had not read such nonsense as Fukuyama’s, they would necessarily have avoided the catastrophes that beset the international order or the woes that afflict many of their countries internally. There are other social processes that promote amnesia or selective perception. In an earlier essay (Mennell, 2015), I suggested how Elias’s theory of established–outsiders relations (Elias and Scotson, 2008) can be applied in the study of international relations. More powerful countries in effect generate ‘praise gossip’ about themselves (read ‘American exceptionalism’) based on a ‘minority of the best’, and ‘blame gossip’ about less powerful countries based on a ‘minority of the worst’. I applied the theory in analysing the crisis in Ukraine starting in 2014, suggesting it as a mechanism promoting American inability to see the consequences of their actions, and in particular to anticipate how their actions would be perceived from the Russian point of view. This is not the place to reiterate the details of that argument. But I suggest that established–outsider processes have played a significant part in bringing about a gross underestimate of the difficulties of promoting and spreading Western conceptions of democracy. And, as a result of the tendency always to look to an idealised stereotype of a minority of the best features of Western democracy, elites may be overlooking the decay of key elements of their own countries’ institutions.

Notes

An earlier version of this paper was read on 13 July 2016 at the International Sociological Association’s Forum 2016, at the University of Vienna, in the session I organised for Research Committee 56, Historical Sociology, Session 645: In what ways can comparative–historical sociology help to improve the workings of the modern world?

The selection of Tocqueville’s writings that John Stone and I edited (Tocqueville, 1980) was expressly intended to demonstrate his deeper sociological insights, offsetting the concentration by political scientists on his discussion of political arrangements more narrowly. See especially our Introduction to the volume, pp. 1–46.

Friedrich Engels, letter to Franz Mehring, 14 July 1893, in Marx–Engels Selected Works, 1968, pp. 699–703. A famous recent study of the phenomenon is Thomas Frank’s What’s the Matter with Kansas? (2004).

See Norbert Elias’s discussion of the gradual ‘parliamentarisation’ of political conflict in Britain, in the period between the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 to the mid eighteenth century, as a consequence of the more or less accidental formation of two fairly evenly balanced ‘parties’ within broadly the same dominant estate of landowners, the Whigs and Tories, eventually alternating in power without civil disorder ensuing (Elias, 2008: 9–23). In Ireland, such a relative balance – in this case between the Protestant Ascendancy landowning class and the mainly Catholic majority of the population of all strata – was precisely what did not come about.

As we have seen with the rise in recent years of populist–nativist movements in Europe and the USA in response to the arrival of large numbers of refugees, asylum-seekers and economic migrants: to mention some of them for the sake of brevity by the names just of their leaders, they include Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, Marine Le Pen in France, Victor Orban in Hungary, Nigel Farage in the UK, and of course Donald Trump in the USA.

For a masterly summary of the history and main elements of neo-liberalism by a distinguished British journalist, see George Monbiot (2016).

References

- Aidt, Toke S. and Peter S. Jensen (2014) ‘Workers of the World, Unite! Franchise extensions and the threat of revolution in Europe,1820–1938’, European Economic Review 72, pp. 52–75.

- Aidt, Toke S. and Raphaël Franck (2015) ‘Democratization under the threat of revolution: evidence from the Great Reform Act of 1832’, Econometrica, 83: 2, pp. 505–47

- Apter, David (1955) The Gold Coast in Transition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Coser, Lewis (1956) The Functions of Social Conflict. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Davis, James C. (1962) ‘Toward a theory of revolution’, American Sociological Review 27: 1, pp. 5–19.

- Elias, Norbert (2008) ‘Introduction’, in Elias and Eric Dunning, Quest for Excitement: Sport and Leisure in the Civilising Process. Dublin: UCD Press [Collected Works, vol. 7].

- Elias, Norbert (2013) Studies on the Germans. Dublin: UCD Press, 2013 [Collected Works, vol. 11].

- Elias, Norbert and John L. Scotson (2008 [1965]) The Established and the Outsiders. Dublin: UCD Press [Collected Works, vol. 4].

- Friedrich Engels, letter to Franz Mehring, 14 July 1893, in Marx–Engels Selected Works. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1968, pp. 699–703

- Frank, Thomas (2004) What’s the Matter with Kansas? New York: Metropolitan Books.

- Fukuyama, Francis (1989) ‘The End of History?, The National Interest, Summer 1989;

- Fukuyama, Francis (1992) The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press.

- Kornhauser, William (1959) The Politics of Mass Society. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Law, Alex and Eric Royal Lybeck, eds (2015) Sociological Amnesia. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin (1960) Political Man. London: William Heinemann.

- Mannheim, Karl (1960 [1936]) Ideology and Utopia. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Marx, Karl (1968 [1852]) The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, in Marx-Engels Selected Works. London: Lawrence & Wishart, pp. 97–180.

- Mennell, Stephen (2015) ‘Explaining American hypocrisy’, Human Figurations, 4: 2, 2015. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/h/humfig/11217607.0004.202/—explaining-american-hypocrisy?rgn=main;view=fulltext. Accessed 6 May 2017.

- Monbiot, George (2016) ‘The zombie doctrine’, Guardian, 16 April.

- Simmel, Georg (1955) Conflict and The Web of Group Affiliations (trans. Kurt H. Wolff and Reinhard Bendix). Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Stone, John and Stephen Mennell, eds (1980) Alexis de Tocqueville on Democracy, Revolution and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Tocqueville, Alexis de (1955) The Old Regime and the French Revolution, trans. Stuart Gilbert. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Tocqueville, Alexis de (1961 [1835–40]) Democracy in America., trans Henry Reeve. 2 vols, New York: Schocken.

- Tocqueville, Alexis de (1980), Alexis de Tocqueville on Democracy, Revolution and Society, eds John Stone and Steven Mennell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.