The Dutch bourgeois civilising offensive in the nineteenth century

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract: The term ‘burgerlijk beschavingsoffensief’(bourgeois civilising offensive) was first coined in 1979 by the Dutch historian Piet de Rooy, in his book on Unemployment in the Netherlands during the Great Depression. Almost thirty five years later, the concept has spread widely and proved very flexible, both in academic circles, and in the media. For example, it has been used to analyze episodes in the Middle Ages, in departmental papers on the relation between government and the art world, and even to study the role of pot plants in civilising working class homes. In this paper I will revisit the origin of the concept.

Keywords: Civilising offensive; The Netherlands nineteenth century; patriotism; civic virtue; cult of domesticity.

Introduction[1]

The concept of the bourgeois civilising offensive – ‘burgerlijk beschavingsoffensief’, in Dutch – will be set out in more detail, from its first formulation in 1979. American historian Christopher Lasch made stimulating comments on the 'forces of organized virtue' in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. In the Dutch Republic of the late eighteenth century, and its successor, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, these forces of organised virtue can be found in the Dutch Society for the Public Good, de Maatschappij tot Nut van ‘t Algemeen, established in 1784. It was this Society which did more than any other to spread the gospel of a virtuous nation in order to achieve more welfare for the emerging unified nation. How did this Society go about it? The burgerlijk beschavingsoffensief was a peaceful one. The poor at whom the offensive was aimed, were seen as fellow human beings, to be helped from their state of misery by teaching them morals, cleanliness and self-control. The nation should be better educated, and schools were seen as a very important institution to achieve this. Schools were important to reach and to teach the children. But adults should be educated too by having them read the pamphlets and books the Society published year after year in abundance. The details of all these efforts and the messages contained in the beschavingsoffensief will be presented in more detail, by tracing the printed legacy of ‘t Nut, as it was affectionately called,. Its archives, in the Amsterdam Stadsarchief (Municipal Archives) are a rich mine of minutiae on the workings of this force of organised virtue, containing hundreds of books, pamphlets and minutes covering the history of ‘t Nutfrom its very start up to the present day. As the nation was seen as suffering from a ‘lack of civilisation’, and was suffering from poverty as a consequence, the moral entrepreneurs, in the terms of Howard Becker (1961), of ‘t Nut set out to improve the lot of the nation by steadfastly preaching the gospel of virtue. In what follows, this will be explored.[2]

Origins of the concept ‘bourgeois civilising offensive’

The concept of the civilising offensive was developed in 1979. Before going into more detail on the bourgeois civilising offensive in the nineteenth century in the Netherlands, it is worthwhile to first explore the intellectual roots of the birth of the concept itself (see also De Regt 2015, this issue). In the late 1970s, the department of the history of education of the University of Amsterdam, where I started working, was trying to develop a social history of education, rather than merely describing the work of great philosophers. A contributory factor to these developments, no doubt, was the influence of the Zeitgeist. Around that time the work of Elias was very inspiring and had influenced many Dutch scholars from a range of academic disciplines. But there were other influences as well; why, as could be expected from a Marxian point of view, were the labouring poor in the Netherlands not more revolutionary? What made them so obedient? Furthermore, Michel Foucault (1975) had published his influential book on the disciplining of the body. What seemed to be lacking, however, was a more grounded explication of the ways in which the poor were subjugated. Here is where the work of the American historian Christopher Lasch comes in. He was interested in tracing where the new Victorian rules for the people in the nineteenth century, which he perceived in the western world, actually came from. Did these new behavioural rules come about spontaneously? He did not perceive this to be a natural process. Instead, he had another solution: ‘Bourgeois domesticity did not simply evolve. It was imposed upon society by the forces of organised virtue, led by feminists, temperance advocates, educational reformers, liberal ministers, penologists, doctors, and bureaucrats' (Lasch 1977: 169). Nor was it caused by the upheaval that the Industrial Revolution had brought about in the nineteenth century. At least in the Netherlands, these ‘forces of organised virtue’ date from an earlier period. However, this moral enterprise was not unique: in many western European countries the Enlightenment inspired the founding of societies struggling for reform of civil society. In the UK, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) was founded in 1824; and movements for the abolition of slavery were formed as early as the end of the eighteenth century, not only in the UK but also elsewhere. Societies comparable to ‘t Nut, which aimed for a virtuous nation and all kinds of betterment of society at large, are hard to find outside of The Netherlands however.

Almost at the same time, in 1797, the Dutch Missionary Society (Het Nederlandsch Zendelinggenootschap) was founded, modelling itself after the London Missionary Society, founded two years earlier, in its interdenominational character (Boone 1997: 15). This Society took over from the Dutch Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC )and the West-Indische Compagnie (WIC), going out of business around 1795, when the Bataafsche Republiek took over from its predecessor. Trade was their mission, but in its wake both the VOC and the WIC were active in the field of converting the natives. In the nineteenth century, this role was taken over by the Zendelinggenootschap. It took upon itself the task of civilising and Christianising the heathens. This task was far beyond their powers however, but it was attempted with great energy and perseverance during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Boone 1997).[3]

Motives in the eighteenth century for intervening in the lives of the poor

It was in the wake of the Dutch Enlightenment, in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, when a host of well-meaning societies sprang up to educate the people and to better their economic situation. The general guiding principle was that poverty was due to the weakness of morals (see also Van Ginkel 2015, this issue). The moral decay, or so it was perceived, of Dutch society was most clearly visible in the experiences and conditions of the poor. Dutch poetess Elisabeth Wolff complained bitterly in 1778 (1977 [1778]: 102):

Good God! Is it really the case that this scum of the nation, living in vice and poverty, in wantonness and sorrow, in excesses and illness, should stem from the same origin as the civilised parts of the people! Are these really creatures formed to Your likeness! Are these people really more than beasts! Are they entitled to eternal happiness! They know of no virtuousness, nor are they able to reason soundly – no more than convulsions of humanity they seem to be.

What could be done to stem the tide? Elisabeth Wolff and others thought it well-nigh impossible to ameliorate the lot of the ‘savage men who were Head of the family’. Instead, their wives, and especially their children (see also, Dolan 2015 and Vertigans 2015, this issue), seemed worthwhile saving through schooling and by whatever means appropriate, ‘clever friends of humanity could invent to better the situation of the poor' (Wolff 1977 [1778]: 104). For the Dutch bourgeois at the time, virtue was not – as it would be seen today – stale and pedestrian, but still glowed with a faint glimmer of heroism. Learned societies such as De Oeconomische Tak (Economical Department), founded in 1777, and De Maatschappij tot nut van ‘t Algemeen (Society for the Public Good) (1784) took up the call to arms. They propagated civil engagement, solidarity and patriotism (Buijnsters 1984: 200).

These forces of organised virtue in the Dutch republic started a real civilising offensive, aimed at the poor and the labouring classes in general. People could and should do something themselves to alleviate their lot: to combat illiteracy, illness, lack of hygiene and brutal habits. The civilising offensive began in earnest in 1784, when the liberal minister, a Mennonite, Jan Nieuwenhuijzen (see illustration 1), founded ‘de Maatschappij tot Nut van ‘t Algemeen’ – the Society for the Public Good (Mijnhardt and Wichers 1984).[4]

In the late eighteenth and nineteenth century, the Netherlands did not fare too well economically. Parts of the middle classes who became members of ‘t Nut feared that the poverty of the people could lead to rebelliousness and unrest, which they tried to temper by preaching to the people to behave decently, to be thrifty, and to abstain from spending their money on gin. In short, they promoted the gospel of the advantages of a quiet and domestic life: they aimed at permanent education of the common people (De Rooy 2014).

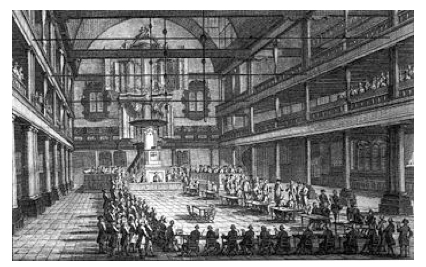

Organising the civilising offensive

After its foundation in 1784, the political tide turned when the French invaded in 1795 and made the Netherlands a more reform-minded Republic, where there was space for a tolerant and, up to a point, liberal Nut. Members joined in their thousands. They donated a ‘ducaat’, five guilders and 25 cents, to become a fully-fledged member. This was no small sum at the time and the lower classes could not afford such an amount. In return, members had the right to vote for their representatives in the General Council that met once a year in Amsterdam (see Illustration 2).

Moreover, they could attend local meetings and they received all the publications of ‘t Nut for free. ‘t Nut soon had up to fifteen thousand members, spread all over the country, who held weekly or monthly meetings, organised by the local departments. These meetings included readings on all kinds of subjects, but mainly on the art of decent living. They were comparable to what in England would become the organisation of university extension at the end of the nineteenth century; and afterwards, members sat together, drinking wine and smoking pipes, forging strong bonds. Indeed, only men were members: women were expected to stay within the private sphere of the home. And anyway, because of the smoking of pipes the prevailing standards of the time dictated that it was improper to have female company. Women, even though they were theoretically very important as guardians of virtue, were not supposed to take part in public discussion outside the home and the family. It was only in 1899 that women could become members on their own, and for the first time in 1901 a woman became a member of the Board (Mijnhardt & Wichers 1984: 65, 113).

In the nineteenth century, over three hundred towns and villages which had their own department of ‘t Nut could pride themselves on their own meeting hall. Many of them had their own lending libraries, savings bank, and, perhaps most importantly, their own primary schools.[5] Savings banks for ordinary people were a new phenomenon. Hitherto, people had no safe depository available for their savings, but instead had to quite literally hide them under their mattresses. Now they could save them in a safe place for hard times, or for investments in their trades.

Children were the most malleable members of society – if they could be reached at an early stage, and influenced in a virtuous direction, then there could be new hope and expectation for the future of the Dutch society. This was what ‘t Nut strove for. From the very start of the Bataafse republiek – 1795, after the French had occupied the Republic – 't Nut had pleaded for general education for all children for the good of the nation.

This would be an important task for the newly founded state: young children should be instructed in how to be civilised citizens. No longer were the churches or local communities responsible for the governance of schools, now the state should oversee a new national form of education, with schoolmasters better-educated and employed and remunerated directly by the national government. This was no less than revolutionary. But after several failures, the new law on primary schools came about in 1806 and remained unchanged for the subsequent half century. This new national law on primary schools of 1806 was very helpful in realising the goals of ‘t Nut and significant attention was given to training the teachers as well. Only in 1857 was it revised. But by then its aims, educating the children according to principles of the new civil society, had more or less succeeded (Schama 1970; Boekholt and De Booy 1987; Bakker et al. 2006). Religiously inspired education was especially taboo for ‘t Nut – it was deemed that this would contribute to an unwanted division between the citizenry. People should feel they were all Dutchmen, citizens of the new Kingdom (after 1814) of the Netherlands, no longer divided along religious lines or local chauvinistic feelings. Disintegration of nation and people – social classes and estates – was to be prevented by this new national system of educating the people.[6] The nation was often compared to a large family, home for all citizens, who should behave according to their status but with different obligations and roles. As to what to do, or what not to do, ‘t Nut tried to educate the people and inculcate lasting habits.

For 't Nut it was of great importance that children, and their parents as well, regarded themselves as citizens of the country as a whole. In their various positions within the social hierarchy everyone should strive, not upwards, but towards doing their utmost to fulfill their duties in whatever rung of society God had willed them to ordain. People should learn that a new moral order was essential for the well-being of society in general, as well as for the well-being of every nuclear family. Charity alone was not enough however, and could even be harmful. People themselves were seen as responsible for their own poverty and misery – they had to see to it themselves that by leading virtuous lives, they could conquer their suffering (Mijnhardt 1988).

The schools were the sites for the civilising and socialising of children, but ‘t Nut tried to reach the adult population of the lower classes as well. This proved to be no easy task. However, ‘t Nut stubbornly devoted much of its energy to the dissemination of the gospel of virtue, mother to all things worth striving for. In the nineteenth century ‘t Nut produced thousands of books and pamphlets with ‘good’ advice and treatises on all kinds of subjects to ameliorate society at large. And also by giving practical solutions as well. One Protestant minister, Ottho Gerhard Heldring (see illustration 4), used to visit his parishioners in the1830s and saw to it that they learned to use the clock he gave them in order to instil timekeeping discipline. In that way they themselves could see to it that they did not waste their time, but used it in as frugally and organised a fashion as possible (Van der Hoeven 1942: 26; see also Thompson 1967).

Just as children are not born civilised but are socialised to living in society, so, one thought, it is with the lower classes: they had to be educated. A Dutch patrician, GK van Hogendorp (GK van Hogendorp, Missive over het Armenwezen 1805: 28, as quoted in HFJM. van den Eerenbeemt 1977: 26) formulated this as follows: ‘the poor, just like children, need to be guided and supervised for a long period of time, in order to teach them how to use their time in a useful way.’

Patriotism and language: towards the unification of the nation

One of the things which had to be learned was the speaking of a common language, no longer only local dialects, but something which could be spoken and understood by all Dutch citizens alike. In 1830 volunteers for the army, trying to keep Belgium from independence by force, came from provinces of all the Northern Netherlands (see illustration 5). After the Napoleonic Wars, the allied forces tried to make Europe safe by forming the new nation-state of the Northern and the Southern Netherlands. This proved too much for the Belgian people who were less than enthusiastic about the reign of King Willem I. Soldiers from Groningen, the most northern (and protestant) province, marched to Belgium, passing through the catholic province of Brabant. They could not understand the language of the local Brabant people, nor did they recognise them as fellow Dutchmen. This was a serious threat for the nationalistic and patriotic feelings that ‘t Nut saw as so elementary for an enlightened nation such as the Netherlands (Knippenberg and De Pater 1988: 37). Belgium, however, was lost, which in 1839 had to be admitted by the Dutch government.

It was surely an exaggeration to maintain that ‘t Nut had taught the Dutch nation how to read and speak – or at least understand the same language – but there is certainly a kernel of truth in this statement, which was made by Dutch minister Abraham Kuyper. Kuyper (1869) opposed ‘t Nut on religious grounds, but nevertheless found much to praise in its civilising work.

Prize treatises as a way of promoting the aims of ‘t Nut

To prevent the dissolution of society, ‘t Nut tried to impose a new social cement: virtue. If this could be achieved then, and only then, would the Dutch nation be in a position to become as influential and wealthy as it was in the ‘Golden Age’ of the seventeenth century. To reach this goal, schools alone would not suffice. All kinds of social questions – such as poverty and unemployment, health and hygiene, family life and domesticity – were debated and were written about in numerous books and pamphlets. Many of these debates were initiated by ‘t Nut and debated in the meetings of the local departments, as well as in the yearly meetings in Amsterdam. It was there that the delegates of the departments could vote for the subject of the yearly prize question. The answer had to be in the form of a book (see Illustration 6). All members could compete for the first prize, and whoever won, received ample reward in the form a gold medal, and the mass publication of their book on a huge scale: a circulation of twenty thousand books was the rule. Every year all members of ‘t Nut received the prize winning book for free, and they were expected to read it thoroughly and to hand it down to their ‘lesser’ fellow citizens. These yearly publications highlight the very serious attempts at improving the lot of the people. Sometimes the books were learned treatises on subjects like hygiene, the right upbringing of children, or how to keep the household in good order. But they also covered geography, biology and a wide range of other interesting topics. When dealing with moral questions, the dialogue style was popular; and where the chief characters debated moral questions their names were, in the style of Dickens, Gentleheart or Virtuelover. One tried in this way to avoid preaching and make for role models instead.

Domesticity was seen as the key virtue, from which all other virtues would spring. A good upbringing for the children, temperance, honesty, a strong work ethic – these were the behaviours and habits that were sought after and which 't Nut tried to inculcate. On the other hand, life outside the family home was seen as dangerous.[7] Dutch Minister Wigeri (1789: 444–445) even went so far as to advise not sending children to schools at all for fear of the bad example the behaviour of their peers would set. However, this was a strategy confined to the rich, who could afford a private home teacher. For everyone else the advice was to keep their children under strict surveillance on the way to and from school: ‘Never let your children out without keeping an eye on them – this is too risky for your children’s health, life, and its virtue’ (Ten Oever 1789: 425; Boing 1790: 136).

The same advice was given to adults: better not play cards, or drink in a tavern. ‘Far better would it be to keep yourselves to yourselves and debate geography’ (Van der Ploeg 1800: 6). An essential part of educating children was inculcating them with healthy feelings of shame and the formation of an alert conscience.[8] If the children were going astray in later life, then it was the parents who were to blame (Clarisse 1802: 22–23). Self-control was warmly advised as the best way to prevent transgression. And for that, parents had to provide a good example. Only then would they be able to steer their children down the right track. And not by beating the children, but by constant supervision: bending, not breaking of their will would be the best way to proceed (Van der Willigen 1820: 32). The internal affairs of any family were the task of the woman and this was true for all classes alike. Women had this sole aim in life: to be wife, mother and educator of the children (Lastdrager 1820: 53). Domesticity being the chief virtue, the woman was the key figure. This was very often seen as lacking in real life – presenting a very serious challenge for ‘t Nut. It would busy itself for the whole of the nineteenth century with this formidable task.

Rewards and medals to make virtue attractive

A system of rewards was founded from the very start of ‘t Nut to promote virtuous behaviour. Words are one thing, but actions and good examples are more worthwhile. These could range from the heroic rescue of people who were drowning, to steadfastly working as a schoolmaster. When discussing all the good works ‘t Nut had done, a member of ‘t Nut sighed: ‘Time and again misery! Time and again dismalness! It seems to be there is nothing but crime and disaster in the world! Trust in goodness is failing, everywhere there seems to be nothing but distrust in human virtuousness’ (Nutsbijdragen 1842). All the more necessary was it to give ample attention to whatever good deeds were done. Such as ‘all those deeds where the perpetrator or perpetrators, with exceptional courage or danger for their own lives, saved or tried to save from immediate or imminent danger one or more of their fellow human beings' (Nutsbijdragen 1835). These rewards could be seen as a counterweight to the perceived ‘bad times’ and would provide an example for all bystanders. Local departments proposed a hero and he (or she, but this was far from the norm) received either a book, an amount of money, a medal, or an honorary membership of ‘t Nut (see illustration 7). In the first half of the nineteenth century a lot of ‘heroes’ were rewarded. In 1826, for instance, no less than 93 people saved someone from drowning or from a dangerous situation on ice; 154 people were rewarded for helping castaways; and another 18 for helping people out of wells, water basins and mines. Water being everywhere in the Low Countries in the evening darkness, in the days before effective street lamps were installed, was a real danger. Only in the twentieth century did learning to swim become part of the upbringing of children. Gradually, the system of rewarding good behaviour changed; the King himself thought it better not to leave these rewards to a private initiative (Algemeen Verslag 1841). Subsequently ‘t Nut shifted from rewarding desired behavioural expectations to mainly praising dutiful working, especially when it came to schoolmasters. But gradually this system faded away as well: pedagogic aims made way for more systemised analyses and reports on the part of ‘t Nut.

Conclusion

By the end of the eighteenth century, social critique on the ‘shocking’ behaviour of the lower classes of society was given a new impetus: instead of simply abhorring them, they should be the subjects of a new educational offensive in a nation where parochialism should make way for patriotic feelings. This would make the nation as a whole more unified and more prosperous. A nation, moreover, no longer divided by religious clefts, but united by a non-doctrinal Christian belief. A real civilising offensive was set up by the forces of organised virtue, with ‘t Nut as the main instigator and driving force; an offensive aimed at educating the people, convincing them of the advantages of avoiding vice and embracing virtuousness and domesticity. Schooling the young, and writing books and pamphlets aimed at adults were the main weapons. Not that the differences between rich and poor, man and woman should vanish. On the contrary, society as a whole was seen as a large family, where all the members had different roles and duties.

How effective was this mass imposition of virtue by the civilising offensive of ‘t Nut? A century of toil and struggle by this well-meaning Society demonstrated two things. Firstly, the middle classes who promoted a virtuous life did indeed drink less, sent their children to school, and were able to deal with the complexities of industrialisation. They themselves seem to have listened to their own advice. The labouring poor on the other hand were, as a rule, not too impressed by, or receptive to, the attacks on their own culture. They proved not to be a blank slate after all, but people with their own culture and behavioural norms; how repulsive their habits often were in the eyes of the bourgeois middle classes (Frijhoff 1984: 19; De Regt 1984; Van Deursen 1987: 433). Obviously, this is not restricted to the relations between the Dutch in the nineteenth century. The Established and the Outsiders, as it was formulated by Elias, is a figuration which seems to be almost universal (Elias & Scotson 1965). Secondly, what is so specific about the civilising offensive of ‘t Nut is the way this dichotomy should be bridged: by peaceful means and persuasion.

Imposing civilisation on people who are regarded as uncivilised, bringing them to adhere to another ethic, is not as easy as it seemed to the members of ‘t Nut. And yet, the beginning of the twentieth century saw a different nation; yes, more civilised, better educated, less drinking, more prosperous as well than a hundred years earlier. Whatever the influence of the organised forces of virtue, domesticity was more accepted as a way of life than ever before (Van der Woud 2010; see also Blom 1993: 31).

Appendix: Figures on membership of 't Nut

| Year | Members | Departments |

|---|---|---|

| 1785 | 345 | 5 |

| 1795 | 2437 | 27 |

| 1805 | 5667 | 66 |

| 1815 | 5428 | 90 |

| 1825 | 12 058 | 175 |

| 1835 | 12 700 | 204 |

| 1845 | 13 821 | 269 |

| 1855 | 14 392 | 304 |

| 1865 | 13 856 | 304 |

| 1875 | 16 645 | 333 |

| 1885 | 17 504 | 343 |

Source: Mijnhardt & Wichers 1984: 359.

Notes: In 1795 the population of the Netherlands stood at 2.08 million inhabitants; in 1850 3.084 million inhabitants (Bevolkingsatlas: 8, 28).

All publications of ‘t Nut were sent freely to all members, expecting them to hand these publications on after reading.

Notes

Thanks to John Flint and Ryan Powell for their comments. And thanks to the anonymous reviewer, who wrote: 'what influence did the imperial/colonial experience play? Some scholars would argue that the civilising mission in the colonies was reflected back to the metropole. The discourse of the "Other" was transposed onto lower classes; like the "savage" encountered in the colonial setting, the lower classes were also perceived as potentially dangerous. As you point out in the paper, the lower classes were considered immoral and unclean, just as the colonial "Other" was. Can the origins of the civilising offensive be found in the colonies? In turn, I was left wondering about the state of the Dutch Empire, and if this had any bearing on the impetus behind civilising the lower classes (it is mentioned that the Netherlands was not faring well economically). This, I think, is also perhaps linked with national efficiency and the need to breed a strong "Imperial race".’ Much more remains to be done in this field, but Boone (1997) is at pains to show the link between the Dutch beschavingsoffensief of ‘t Nut and the colonial experience.

Dutch historian Piet de Rooy coined the phrase ‘burgerlijk beschavingsoffensief’ in his book Werklozenzorg en werkloosheidsbestrijding 1917–1940. Landelijk en Amsterdams beleid. Amsterdam, Van Gennep,1979: 9–10. (The care for the unemployed and the struggle against unemployment. National and Amsterdam policy, 1917–1940) The first version of my working on this concept: Bernard Kruithof, ‘De deugdzame natie. Het burgerlijk beschavingsoffensief van de Maatschappij tot Nut van ‘t Algemeen tussen 1784 en 1860’. Symposion, Tijdschrift voor maatschappijwetenschap, vol. 2, number 1, 1980: 22–37 (The virtuous nation. The bourgeois civilising offensive of the Society for the Public Good; 1784–1860); a more elaborated version in Bernard Kruithof, Zonde en deugd in domineesland. Nederlandse protestanten en problemen van opvoeding, 17e tot 20e eeuw. Groningen, 1990; (Sin and virtue in the land of ministers. Dutch protestants and education, 17th–20th century); this article is based upon Bernard Kruithof, ‘Godsvrucht en goede zeden bevorderen.’ Het burgerlijk beschavingsoffensief van de Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen. In: Nelleke Bakker, Rudof Dekker & Angélique Janssens, red., Tot burgerschap en deugd. Volksopvoeding in de negentiende eeuw. Hilversum, 2006: 69–81 (On the promotion of civility and virtue in the nineteenth century).

Though Boone (1997) concentrates on the period 1840–1865, he pays much attention to the concept of beschavingsoffensief as very useful for the colonial experience.

Some figures on membership in the attachment of this article.

Some figures on membership can be found in the Appendix of this article.

A.J. Lastdrager, Onderzoek naar de beste middelen ter vorming en bevestiging van het Nederlandsch volkskarakter. Amsterdam, 1820. (Essay on how to establish and ameliorate the Dutch national character) There are many more pamphlets written by members of 't Nut dealing with these problems of nationbuilding. Simon Schama (1970: 600–601) commented: 'The leaders of the reform movement (mainly schoolmasters, bk) were treated as a new clergy, one which had captured the moral initiative and the popular allegiance from its established competitors. This was perhaps the most distinctive feature of educational reform in the Netherlands: the conjunction of moral evangelism with organisational efficiency. Indeed one might go further and suggest that the presence of the former was a condition of the success for the latter.’

See also Richard Sennett (1978: 95–96): ‘The special task the family could perform, nurturance of those who are helpless, came to seem a natural function of “the” family. Nurturance detached the family from social arrangements.’

This is, of course, a central focus in the work of Norbert Elias.

References

- Algemeen Verslag van ’t Nut 1841, 1842, 1845

- Bakker, Nelleke, Jan Noordman & Marjoke Rietveld-Van Wingerden (2006) Vijf eeuwen opvoeden in Nederland. Idee en praktijk. 1500–2000 (Five centuries of education in the Netherlands. Ideals and practices. 1500–2000). Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum

- Bevolkingsatlas van Nederland. Demografische ontwikkelingen van 1850 tot heden (Demographical Atlas of the Netherlands 1850–2003). Elmar: Rijswijk, 2003

- Blom, J.C.H. (1993) ‘Een harmonisch gezin en individuele ontplooiing. Enkele beschouwingen over veranderende opvattinngen over de vrouw in Nederland sinds de jaren dertig. ’Bijdragen en Medededlingen betreffende de geschiedenis der Nederlanden BMGN vol. 108, number 1. (A harmonious family and individual expansion. Some comments on changing opinions on the role of women in the Netherlands from the thirties onwards.)

- Boekholt, P.Th.F.M. & E.P. de Booy (1987) Geschiedenis van de school in Nederland vanaf de middeleeuwen tot aan de huidige tijd. Assen/Maastricht: Van Gorcum (A history of schools in the Netherlands from mediaval times till the present)

- Boing, D. (1790) Schets van den braaven man in het gemeen burgerlijk leven, Amsterdamp (An essay on the virtuous man in everyday life).

- Boone, A.Th. (1997) Bekering en beschaving. De agogische activiteiten van het Nederlandsch Zendelinggenootschap in Oost-Java (1840–1865). Zoetermeer: Boekencentrum (Conversion and civilization. Eastern-Java, 1840–1865)

- Buijnsters, P.J. (1984) Wolff en Deken. Een biografie. Leiden. (Wolff and Deken. A biography)

- Clarisse, H.W. (1802) Middelen om de losheid in grondbeginselen en zeden te stuiten, Amsterdam. (How to remedy the looseness in principles and ethics).

- Deursen, A.F.Th. van (1987) ‘Om het algemeen volksgeluk’, Theoretische geschiedenis, 14 pp. 429–433, Eerenbeemt, H.F.J.M. (1977) Armoede en arbeidsdwang. Werkinrichtingen voor ‘onnutte’ Nederlanders in de republiek, 1750–1795. Een mentaliteitsgeschiedenis. Den Haag (Poverty and forced labor. Institutional care for ‘useless’ men in the Republic, 1750–1795. A history of mentalities)

- Elias, N. & Scotson, J. L. (1965) The Established and the Outsiders. London: F. Cass.

- Elias, N. (1977 [1939]) Über den Prozess der Zivilisation. Suhrkamp (The civilizing process).

- Hoeven, Adrianus van der (1942) Otto Gerhard Heldring. Amsterdam.

- Foucault, Michel (1975) Surveiller et punir. Naissance de la prison, Paris. (Discipline and punish. The birth of the prison).

- Frijhoff, Willem T. (1984) Cultuur, mentaliteit: illusies van elites?, Nijmegen: SUN (Culture, mentality: illusions of elites?).

- Knippenberg, Hans & Ben de Pater (1988), De eenwording van Nederland. Schaalvergroting en integratie, Nijmegen: SUN (On the unification of the Netherlands, enlargement of scale and integration)

- Kruithof, Bernard, (1980) ‘De deugdzame natie. Het burgerlijk beschavingsoffensief van de Maatschappij tot Nut van ‘t Algemeen tussen 1784 en 1860’. Symposion, Tijdschrift voor maatschappijwetenschap, vol. 2, number 1.: 22–37 (The virtuous nation. The bourgeois civilizing offensive of the Society for the Public Good; 1784–1860)

- Kruithof, Bernard (1990) Zonde en deugd in domineesland. Nederlandse protestanten en problemen van opvoeding, 17e tot 20e eeuw. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff. (Sin and virtue in the land of ministers. Dutch protestants and education, 17th–20th century)

- Kruithof, Bernard (2006) ‘Godsvrucht en goede zeden bevorderen.’ Het burgerlijk beschavingsoffensief van de Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen. In: Nelleke Bakker, Rudof Dekker & Angélique Janssens, red., Tot burgerschap en deugd. Volksopvoeding in de negentiende eeuw. Hilversum: Verloren: 69–81 (On the promotion of civility and virtue in the 19th century).

- Kuyper, Abraham (1869) De Nutsbeweging. Amsterdam. (The ‘Nuts’movement.)

- Lasch, Christopher (1977) Haven in a heartless world. The family besieged. New York: Basic Books

- Lastdrager, A.J. (1820) Onderzoek naar de beste middelen ter vorming en bevestiging van het Nederlandsche volkskarakter, Amsterdam (Inquiry into the best means to establish the Dutch national character).

- Mijnhardt W.W. & A.J. Wichers, eds. (1984)Om het algemeen volksgeluk. Twee eeuwen particulier initiatief 1784–1984. Gedenkboek ter gelegenheid van het tweehonderdjarig bestaan van de Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen. Edam (Memorial book on 200 years Society for the Public Good, 1784–1984)

- Mijnhardt, W.W. (1988) Tot Heil van ’t Menschdom. Culturele genootschappen in Nederland, 1750–1815. Amsterdam ( For the happiness of mankind. Cultural Societies in the Netherlands, 1750–1815).

- Nutsbijdragen 1835, 1842

- Oever, H.H. ten (1798) De zedelijke opvoeding der kinderen, Amsterdam (On moral upbringing of children)

- Ploeg, H.W. van der (!800) De volksverlichting. Amsterdam. (On Enlightenment of the people)

- Regt, Ali de (1984) Arbeidersgezinnen en beschavingsarbeid. Ontwikkelingen in Nederland 1870–1940. Amsterdam (Laboring families and civilizing labor. The Netherlands, developments 1870–1940.)

- Rooy, Piet de (1979) Werklozenzorg en werkloosheidsbestrijding 1917–1940. Landelijk en Amsterdams beleid. Amsterdam: Van Gennep, (The care for the unemployed and the struggle against unemployment. National and Amsterdam policy, 1917–1940)

- Rooy, Piet de (2014) Ons stipje op de waereldkaart. De politieke cultuur van Nederland in de negentiende en twintigste eeuw. Amsterdam: Nieuw Amsterdam. (Our little dot on the world map. Dutch political culture in the nineteenth and twentieth century)

- Schama, Simon (1970) ‘Schools and politics in the Netherlands, 1796–1814’, II, The Historical Journal, 13/4: 589–610.

- Sennett, Richard (1978) The Fall of Public Man. On the social psychology of capitalism. New York

- Thompson, E.P. (1967) ‘Time, work–discipline and industrial capitalism’, Past and Present 38: 56–97.

- Wigeri, J. (1789) De zedelijke opvoeding der kinderen, Amsterdam (Moral upbringing of children).

- Woud, Auke van der (2010) Een koninkrijk vol sloppen. Achterbuurten en vuil in de negentiende eeuw. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker (A kingdom full of slums. Slums and garbage in the nineteenth century)

- Willigen, P. van der (1820) De kracht en invloed der gewoonte, Amsterdam (The force and influence of habit)

Biography

Bernard Kruithof (1952) studied History at the University of Amsterdam. He defended his dissertation Zonde en Deugd in Domineesland (Sin and virtue in the Land of Ministers: Dutch Protestants and Education, Seventeenth–Twentieth Century) in 1990. He has published widely on the history of education and on Dutch social history. Currently he is a Teacher at the Department of Social Sciences and at the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies, University of Amsterdam.