Gender, Sexual Identity, and Families: The Personal Is Political

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Chapter 7: Predicting First Sex among African American Adolescents: The Role of Gender, Family, and Extra Familial Factors

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Risky sexual behavior can take many forms, including early intercourse, multiple partners, and inconsistent use of protection. Early age of first sex (initiation before age 16) is an important indicator of exposure to the risk of pregnancy and risk of sexually transmitted infections during adolescence (Jordahl & Lohman, 2009). Of particular concern are the reports from the Centers for Disease control (CDC) that identify African American adolescents as initiating sexual intercourse at an earlier age than do other ethnicities (CDC, 2014). Current understanding about risk factors for early sexual debut among African Americans is limited due to use of small, nonrepresentative samples, and cross-sectional analyses (Luster & Small, 1994). There is a critical need for greater understanding of predictors of sexual risk taking for African Americans that can guide policies for prevention of STDs and delay of sexual initiation within this group.

The socio-ecological framework (adapted from Bronfenbrenner’s ecological perspective) proposed by DiClemente, Salazar, Crosby, and Rosenthal (2005) suggests that various factors within the individual (including psychological characteristics), the family, and other social contexts may be associated with adolescents’ behaviors, particularly sexual risk behaviors. Researchers have identified parenting and familial factors such as communication about sex, family structure, and monitoring, as key correlates of sexual initiation and sexual risk behaviors (e.g., Hutchinson, 2002; Luster & Small, 1994; Majumdar, 2005). A second aspect involves adolescents’ relationships outside of the immediate family in the neighborhood and school as predictors of sexual debut (e.g., Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004). Thirdly, religiosity and academic performance are examples of individual level factors associated with initiation of first sex (e.g., Frisco, 2008; Meier, 2003).

Informed by DiClemente et al.’s (2005) socio-ecological theoretical framework, the purpose of this study is to examine how, studied together, individual, family, and community factors predict the initiation to first sex among African American adolescents. The research is a secondary analysis of a large national longitudinal data set.

Socio-ecological Model

According to DiClemente et al.’s (2005) socioecological model, individuals’ behaviors should be examined from multiple contexts, including psychological factors, family, relational, and community/societal contexts. In the current study, factors at the individual level (religiosity, academic aspirations, self-esteem, depression), family (social relationships, communication, and family support), and community/societal (neighborhood connectedness and school connectedness) are considered. Adolescents are exposed to each of these interdependent levels on a daily basis. In support of the socio-ecological theoretical framework, Ritchwood, Traylor, Howell, Church, and Bolland (2014) examined self-worth, social relationships (parents and peer), and neighborhood factors and their associations with sexual behaviors of adolescents among African American male and female adolescents in the Deep South. They found that individual, parental, and neighborhood factors were predictive of sexual behaviors (Ritchwood et al., 2014). Such findings emphasize the importance of understanding prior individual and social factors that are directly associated with and interact with gender to also predict later sexual behaviors. As well, such research should be expanded to embrace youth represented in a national data set.

Individual Factors and Sexual Initiation

Adolescents play a role in their own sexual behavior and sexual decision-making processes (Buhi & Goodson, 2007). Often referred to as intrapersonal factors, attributes such as religiosity, academic aspirations, self-esteem and depression, are correlates of adolescent sexual behaviors and initiation to first sex.

Adolescent Religiosity

Religiosity has been defined in multiple ways. For this study, adolescent religiosity is conceptualized as beliefs and participation in religious activities, including church attendance (Meier, 2003; Thornton & Camburn, 1989). According to Thornton and Camburn (1989), religious groups tend to discourage premarital sex and adolescents may hear frequent messages about the dangers of premarital sex. Meier (2003) and Rostosky, Regenerus, and Wright (2003) found that high religiosity reduced the probability of having sex for adolescents of various ethnic backgrounds. A definitive conclusion about whether or not these beliefs deter African American adolescents from initiating intercourse is yet to be established.

Similarly, Manlove, Terry-Humen, Erum, Ikramullah, and Moore (2006) examined the relationships between parent and family religiosity and timing of sexual initiation and contraceptive use, using a sample of sexually inexperienced youth between 12 to 14 years old at base line. Follow-up was conducted five years later. The results from this longitudinal study indicated that more frequent parent religious attendance and activities were related to later age of sexual initiation. African American parents were about twice as likely to attend religious services more than once per week compared to Hispanic and White parents (Manlove et al., 2006). However, family religiosity was independent of sexual initiation among African American adolescents. Their study did not address adolescents’ own religiosity.

There is consistency in the literature regarding the protective nature of religiosity for adolescents. However, inconsistencies appear with regard to the effect across gender. Bearman and Bruckner (2001) and Rostosky et al. (2003) found that the protective effect was stronger for females than for males. Further, Bearman and Bruckner (2001) found that when adolescents took a virginity pledge, the length of delay to sexual debut was longer for females than for males. Given the gender differences found in the timing of sexual initiation and the protectiveness of religiosity, this study examined differences among African American male and female adolescents.

Academic Aspirations

Academic aspiration is defined as adolescents’ beliefs about their future, specifically goals for high academic achievement and plans to attend college (e.g., Honora, 2002). Earlier initiation of first sex has been theorized to be associated with poorer academic performance (Dryfoos, 1990) and students with higher educational aspirations are more likely to postpone sexual intercourse (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990). More specifically, initiation of sex was associated with a reduced focus on future academic goals (e.g., Brooke, Balka, Abernathy & Hamburg, 1994). Jessor’s (1991) problem behavior theory (PBT) included a construct named “limited perceived chances” for success in life (p. 602) as a risk factor for problem behaviors including risky sex. This construct is similar to the construct used in the current study to measure academic aspirations; the adolescents’ beliefs about whether they will attend college. Using PBT as a framework, Costa, Jessor, Donovan, and Fortenberry (1995) examined factors associated with first sex and found that expectation for achievement was associated with a delay in intercourse. Spriggs and Tucker-Halpern (2008) and Frisco (2008) reported that academic goals were associated with delayed intercourse. Additionally, Frisco (2008) used the concept of aligned ambition to demonstrate that adolescents with higher educational goals were expected to understand the consequences of their actions and make smart decisions. Frisco (2008) examined the likelihood of postsecondary enrollment and found that adolescents who initiated sex during high school were less likely to attend college. Schvaneveldt, Miller, Berry, and Thomas (2001) also found that when both adolescents and parents had education goals for the future, sexual debut was delayed. The association was strongest for young black women. Future academic aspirations reflect adolescent beliefs in themselves and it is expected that these factors will be associated with decreased risk for early sexual initiation among African American youth.

Adolescent Depression and Self-Esteem

Depression and self-esteem are important internalizing factors associated with sexual behavior (e.g., Ritchwood et al., 2014). Depressive symptoms are associated with earlier initiation to first sex. Hallfors, Waller, Bauer, Ford, and Halpern (2005) indicated that sex may be seen as a method to “medicate” or alleviate feelings of depression or isolation. Depression is also expected to diminish cognitive capacity and self-efficacy and results in decreased motivation and confidence in adolescents’ ability to resist pressures for sex (Schuster, Mermelstein, & Wakschlag, 2013). For example, using the Add Health data, Harris, Duncan, and Boisjoly (2002) examined the association between “having a nothing to lose attitude” (p. 1029 (including emotional distress) and subsequent risk behaviors, including drug use and early sexual onset. Among adolescents 13-15 years old, emotional distress was associated with early onset of sex. For depressive symptoms, McLeod and Knight (2010) indicated that, among adolescents who initiated sex by age 15, higher levels of depression were observed compared to adolescents who did not initiate by age 15. These findings support the idea that sex might be used to alleviate feelings of depression but do not address these issues specifically among African American adolescents.

There are mixed findings about self-esteem and sexual behavior. Several studies have found that lower levels of self-esteem are associated with earlier initiation of sex (Ethier et al., 2006). In a recent study, Longmore and colleagues (2004) used the Add Health data (similar to the current study) to examine the impact of self-esteem and depression on sexual debut and found that depressive symptoms had a greater impact than self-esteem on sexual onset. Longmore and colleagues (2004) reported that higher self-esteem was associated with sexual debut at older ages for boys and that compared to White girls, depressive symptoms had weaker effects for Black girls. Therefore, higher self-esteem may exert a positive influence for girls leading to a delay in initiation to first sex. Also using the Add Health data, Wheeler (2010) found that higher self-esteem was not significantly correlated with sexual debut one year later. Although the research is inconclusive, it is evident that both self-esteem and depression are associated with first sex, however, there exist differences across gender. Furthermore, when ethnicity was considered there were differences among those of differing ethnicities.

Family Factors and Sexual Initiation

Studies have consistently shown that various parenting practices such as communication, monitoring, and support are associated negatively with initiation to first sex for adolescents (e.g., Sieving et al., 2000). For this study, two types of parent-adolescent communication are considered: (a) general communication and (b) communication about sex with parents. General communication refers to parent and adolescent discussions of everyday activities, such as school and peer relationships. Communication about sex refers to how frequently parents and adolescents hold discussions about safe sex practices, abstinence, and consequences associated with sexual behavior.

Parent-adolescent communication in regards to sexual activity is generally viewed as important and desirable and is perceived as a means of encouraging adolescents to engage in responsible sexual behavior and delay initiation (Hutchison, 2002; Moore & Rosenthal, 1993). However, Davis and Friel (2001) reported that for both male and female adolescents, discussions with mother about sex were associated with earlier initiation of sex. Similarly, Frederick’s cross-sectional study (2008) found that communication was positively associated with sexual behavior It was unclear which occurred first, sex or communication about sex. Current explanations for these contradictory findings include: (a) incongruent reports from parents and adolescents (Lefkowitz, Romo, Corona, Au, & Sigman, 2000); and (b) uncertainty about whether sex occurred before or after communication began (Meschke, Zweig, Barber, & Eccles, 2000). The current study uses parents’ reports on communication about sex and adolescent reports on general communication. With the inclusion of only virgins at Wave I for the current study, communication about sex at Wave I preceded first sex.

Apart from specific communication about matters pertaining to communication about sex, Hutchison (2002) found that general communication between parents and adolescents was the greatest predictor of sexual communication. McNeely et al. (2002) indicated that increased mother-adolescent communication was associated with a delay in early intercourse. As well, poor parent-adolescent communication predicted a range of problem behaviors including drug use, delinquency, and early sexual activity (Loeber & Dishion, 1983). Moreover, communication about sex occurred more among parents (mostly mothers) and daughters than among parents and sons (Hutchinson, 2002). These findings suggest that communication about day-to-day activities may foster closeness between parents and adolescents, increase communication about sex, and prevent or delay adolescent problems.

Family Structure and Family Support

Apart from communication, other family characteristics associated with the timing of sexual intercourse/safe sex practices include family support, family composition, economic status, and parent-child relationships (McNeely et al., 2002; Sieving, Clea, McNeely, & Blum, 2000). Parents transmit their standards of conduct to their children both directly and indirectly (Kotchick, Shaffer, Forehand, & Miller, 2001). Greater parent education predicted older age of first sex among female adolescents (Miller et al, 1997). In the case of African Americans, Murry (1996) found that African American adolescents (n = 109) who lived in two-parent households that had engaged in conversations with parents about sexual issues, and had greater knowledge about sexual matters were more likely to delay age at first intercourse until 18 years of age and beyond. Although the Murry study looked specifically at a sample of African American adolescents, the sample size was relatively small and the findings could not be generalized to African American populations in general. Using a Dutch sample of adolescents 12-17 years old to examine the association between family cohesiveness and sexual debut, de Graff, de van de Schoot, Woertman, Hawk, and Meeus (2012) reported that family cohesion was associated with a delay in sexual intercourse. In particular, girls who came from families with lower cohesion had their first sexual experiences earlier than girls from families with greater levels of cohesion. On the other hand, studies by Kalina et al. (2013) and Longmore, Manning, and Giordano (2001) indicated that parental monitoring had a stronger impact on delaying intercourse than parental or family support.

Community Factors and Sexual Initiation

Outside the purview of individual factors and parent factors, there are peers, neighborhood, and school that are associated with age of sexual debut. In a longitudinal study focusing on adolescents between 12 and 15 years old in Chicago, Browning et al. (2004) found that neighborhood collective efficacy delayed sexual onset only for adolescents who experienced greater levels of parental monitoring. Neighborhood collective efficacy was measured, in part, by adolescents’ reports about whether there are people in their neighborhoods who they can trust, people who watch out to ensure children are safe, and whether there are adults that children can look up to. The Browning et al. (2004) study is among the few that looks beyond neighborhood disorganization to consider neighborhood relationships and connections. Similarly, Moore and Chase-Lansdale (2001) focused on African American girls living in poor communities: girls who initiated sex or became pregnant perceived less social support from neighbors. Moore and Chase-Lansdale (2001) also concluded that a greater degree of outside the home social support compared to a lower degree of such social support was also protective.

Connectedness to school should also delay sexual onset. School connectedness (i.e., “the extent to which students feel accepted, valued, respected, and included in the school”; Shochet, Dadds, Ham, & Montague, 2006, p. 170), is associated with positive health outcomes (Shochet et al., 2006) and prosocial behaviors (Markham, et al., 2010; McNeely & Falci, 2004; McNeely, Nonnemaker, & Blum, 2002). Paul, Fitzjohn, Herbison, and Dickson (2000) indicated that, among adolescents in New Zealand, individual and school factors (connectedness to school) appeared to be more important than family composition or socioeconomic status in the decision to have sexual intercourse before age 16. In addition, Mitchell, Rumbaugh-Whitesell, Spicer, and Beals (2007) found that boys who felt more attached to school and reported higher grades were more likely to postpone sexual initiation in contrast to boys who felt less connected to school. The studies reviewed suggest that greater connectedness to school is associated with prosocial behaviors which may include delay in sexual initiation. The current study focuses on how feelings of connectedness to school and neighbors may protect adolescents from engaging in sexual intercourse. This is an important research focus given the limited scholarship on how connectedness outside of the family is linked to African American adolescents’ risk behaviors, specifically, early initiation of first sex.

The Current Study

Weaknesses of previous studies include: lack of theory, lack of longitudinal designs, small sample sizes, limited geographical area, and studying variables in isolation. Informed by a socio-ecological theoretical framework, the purpose of this study is to examine how individual, family, and community connections predict the initiation to sexual initiation among African American adolescents using a large national longitudinal data set. The current study first assesses the extent to which the initiation to first sex is predicted by levels of individual variables (age, gender, religiosity, self-esteem, depression, academic aspirations), family variables (parent education, family structure, family support, parent-adolescent communication, and communication about sex), and community variables (school and neighborhood connectedness). Second, the study examines the extent to which gender moderates the associations between the predictor variables and the outcome (initiation to first sex).

Study Hypotheses

Given that prior studies have generally indicated that individual/psychological factors such as greater depression, lower academic aspiration, lower religiosity, and lower self-esteem, are negatively associated with risky behaviors, this study hypothesizes that the lower the (a) academic aspirations, (b) religiosity, (c) self-esteem and (d) the higher the depression, the more likely adolescents will be to initiate sex. As well, gender and age should be predictors, with more boys and those who are older more likely to become nonvirgins at Wave II.

Contradictory findings have been reported for the association between parent communication and adolescent sexual behaviors. Some studies found that parent-adolescent communication about sex was negatively associated with sexual risk behavior including early sex (Moore & Rosenthal, 1993) and others reported that communication was positively related to risky sexual behavior and early sex (e.g., Davis & Friel, 2001). Given measurement of antecedent variables at least 12 months prior to the outcome variable, this study hypothesizes that virgin adolescents exposed to less/lower (a) parent education, (b) two-parent family structure, (c) family support, (d) parental communication, and (e) parental communication about sex, will be more likely to initiate sexual intercourse.

Moore and Chase-Lansdale (2001) posit that adults in the community may provide additional social support for adolescents that may protect against negative outcomes for adolescents. This connection to others in the community or neighborhood has been associated with a delay in sexual intercourse (e.g., Browning et al., 2004; Moore & Chase-Lansdale, 1999). Additionally, feelings of connectedness to school have also been associated with delay in sexual intercourse (e.g., Mitchell, et al., 2007). Associations of school connectedness and neighborhood connectedness with outcomes for African American adolescents are understudied. This study hypothesizes that adolescents exposed to lower (a) neighborhood connectedness and (b) school connectedness will be more likely to initiate into sexual intercourse.

In addition, national data suggest that males tend to initiate sex at younger ages than females (CDC, 2009) and that parents are more likely to discuss issues of sex more with female adolescents than males (Hutchinson, 2002). Therefore, this study examines gender differences as a moderator of the association of variables with initiation to sexual initiation. Because previous studies haven’t consistently tested for moderating effects, we look at all the predictors as possibly moderated by gender. However, based on the literature, there should be effects of gender on the associations of specific predictors of first sex. The final hypothesis predicts that the association of familial factors (parent education, general communication, and communication about sex), individual factors (religiosity and future academic aspirations), and extra-familial factors (neighborhood connectedness and school connected) with the outcome are expected to be stronger among girls than boys.

Method

This study uses data from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health (Add Health), which measures social contexts (e.g., families, friends, schools, and neighborhoods) and adolescent health and risk behaviors across time. For this study, we use data from Waves I (1994-1995) and II (one year later, 1996). Wave I included a parent questionnaire which measured parent education (most reports came from mothers) and as well as parent-adolescent communication about sexual activity. Overall, there was oversampling for middle and upper class African Americans as well as Hispanics and Asians in order to have more representative samples of youth in the entire US population (Harris et al., 2003).

Adolescents in the in-home sample from both Waves I and II completed an audio computer assisted survey, a method used to capture sensitive topics such as substance use and sexual behavior. For more sensitive topics, the respondent listened through earphones to pre-recorded questions and entered the answers directly. This lessened the potential for interviewer or parental impact on adolescents’ reports about their behavior. Lastly, a parent, preferably the resident mother of each adolescent respondent interviewed in Wave I, was asked to complete an interviewer-assisted, optically scanned questionnaire.

Sample Demographics

For the purpose of this study, the participants included in the analyses were those who answered Black or African American to the question, “Which one category best describes your racial background?” The adolescents’ age was calculated from the reported birth date and the year and month of the interview. Adolescents between the ages of 11-15 (M = 14.36) who were virgins at Wave 1 were included in the analyses. The rationale for selecting early to middle adolescents stems from previous scholarship which suggests that engaging in sexual activity at age sixteen or older can be considered normative adolescent behavior (Millstein, 2003). Having intercourse in early adolescence is considered risky sexual behavior. At Wave I there were 1205 (51%) African American adolescents who were virgins in the age range 11-15 (n = 511 boys, n = 698 girls). Parental education (reported mainly by mothers) was based on the following question, “How far did you go in school?” Items were recoded into the following categories: 0 = no college experience and 1= at least some college experience or obtained a college degree and postgraduate; 14% of the sample did not report on education.

Dependent Variable

Sexual initiation. To determine whether adolescents had engaged in sexual activity the answers to the question: “Have you ever had sexual intercourse?” was 1= yes, and 0 = no. This variable was used across both waves. At Wave I, the question was used to select virgins and at Wave II to determine whether participants had initiated sex in the intervening year. Of the 1205 virgins at Wave I, 731 of these participated again (61%) at Wave II. There were 156 nonvirgins at Wave II, 21% of the returnees. To assess potential differences between the participants lost through attrition and those who remained at Wave II, we compared these two groups on the variables of the study with chi-square and MANOVA. Older adolescents, parents with no college degree, and females returned more than did younger adolescents, parents with a college degree, and males. Descriptive statistics on all study variables can be found in Table 1.

Individual Factors

Religiosity. Previous Add Health users have used the means of three items to measure adolescent religiosity (e.g., Meier, 2003). These Wave I items included the frequency of attendance at religious services, frequency of attendance at religious youth activities, and self-rated importance of religion: “In the past 12 months, how often did you attend religious services?”; “How important is religion to you?”; and “Many churches, synagogues, and other places of worship have special activities for teenagers—such as youth groups, Bible classes, or choir. In the past 12 months, how often did you attend such youth activities?” For the attendance item, participants responded on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = never to 4 = once a week or more. For the other items responses ranged from 1 = not at all important to 4 = very important. The 3 items were averaged (alpha = .62).

Academic aspirations. At Wave I the mean of two items was used to measure future academic aspirations: “How much do you want to go to college?” and “How likely it is that you will go to college?” Participants responded on a scale of 1 indicating low to 5 indicating high (alpha = .72).

Self-esteem was assessed at Wave I, with four items from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Sample questions included: “Do you agree or disagree that you have many good qualities” and “Do you agree or disagree that you have a lot to be proud of?” The response scale ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree (alpha = .81).

Depression was measured with a modified version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD) which includes twenty items comprising six scales reflecting major facets of depression: depressed mood, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbance (Radloff, 1977). Participants in the current study responded to 12 items, such as “In the past 12 months, how often have you laughed a lot” (reverse scored) and “...how often have you cried a lot.” Responses ranged from 0 = never to 3 = most or all of the time (alpha = .84).

Familial Factors

Parental communication about sex. The parental communication about sex scale consisted of five items from the parent questionnaire in Wave I: “How much have you and {adolescent} talked about: (his/her) having sexual intercourse and the negative or bad things that would happen if [he got someone/she got] pregnant?; The dangers of getting a sexually transmitted disease?; The negative or bad impact on (his/her) social life because (he/she) would lose the respect of others?; The moral issues of not having sexual intercourse?; and How much have you talked to {adolescent}: about birth control; about sex?” The adolescent’s mother (primarily) answered these with 1 = not at all, 2 = somewhat, 3 = a moderate amount, 4 = a great deal (alpha = .90). This measure of communication about sex has been used by other Add Health researchers (Majumdar, 2005) with a reported Cronbach’s alpha of .93.

General communication. Three items measured general communication between adolescents and parents at Wave I. Adolescents were presented with a series of questions regarding things they have done with their parents in the past week. Three items that referred to communication were selected: (1) had a talk about a personal problem; (2) talked about schoolwork or grades; (3) talked about other things they were doing in school. Adolescents answered yes = 1 or no = 0 to these questions. A sum of these items measured general communication (alpha = .57). Ornelas, Perreira, and Ayala (2007) used these items and reported an alpha of .54.

Family Structure. Similar to Lynam et al. (2000), we classified family structure as traditional or nontraditional. Approximately half of the sample (51%) resided in families with two biological parents (coded as 1; others coded as 0).

Family support. Two scales measured adolescents’ relationships with their fathers and mothers. Both scales used four items to measure the closeness, warmth, and level of communication within parent-child relationships. Items included “How close do you feel to (name of dad)?” and “Are you satisfied with the way (name of mom) and you communicate with each other?” Responses were on a 5-point scale with reverse coding so that a high score on these items represented high quality relationships with parents. The Father-Relationship and Mother-Relationship scales were averaged, with alphas of .89 and .85, respectively.

Community Factors

Neighborhood connectedness. Three Wave I items assessed adolescents’ connectedness to neighbors: “You know most of the people in your neighborhood”; “In the past month, you have stopped on the street to talk with someone who lives in your neighborhood”; and “People in this neighborhood look out for each other.” Adolescents indicated if this was true = 1 or false = 0. These items were summed (alpha = .53). Danso (2014) used these items to compose a neighborhood social capital scale.

School connectedness. Three items from Wave I were used to indicate school connectedness: “You feel close to people at your school”; “You feel like you are part of your school”; and “You are happy to be at your school”. These items were reverse coded so that 1 indicated strongly disagree and 4 indicated strongly agree (alpha = .72). McNeely et al. (2002) also used this measure of school connectedness and reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .79.

Results

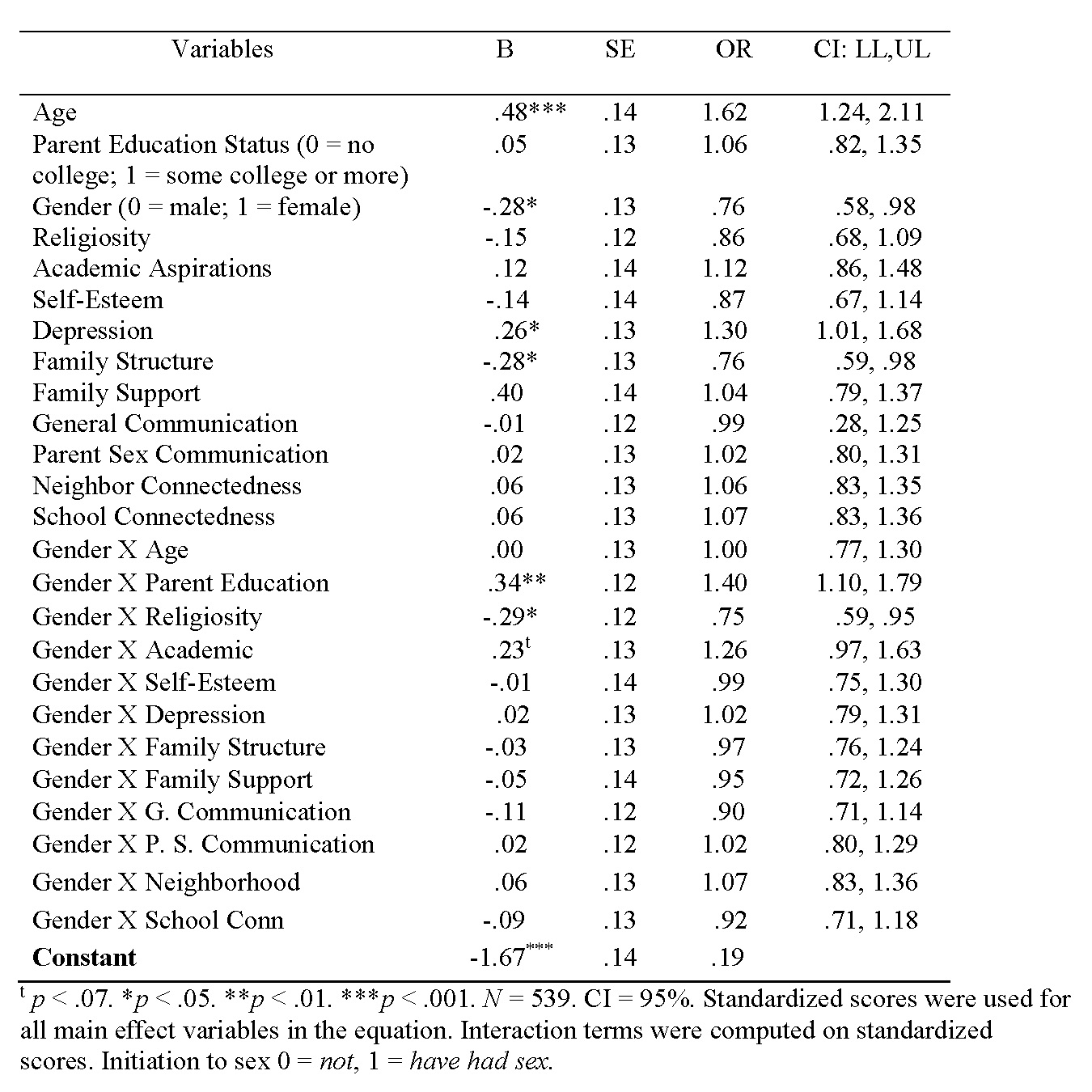

The focus of the study was on adolescent initiation to first sex between Waves I and II. Of the 731 participants in Wave II, 156 had sexual intercourse after Wave I. Due to the binary nature of the Wave 2 outcome variable (have sex/not have sex), hierarchical logistic regression was used to test the hypotheses. Main effects and interaction results are reported in Table 2.

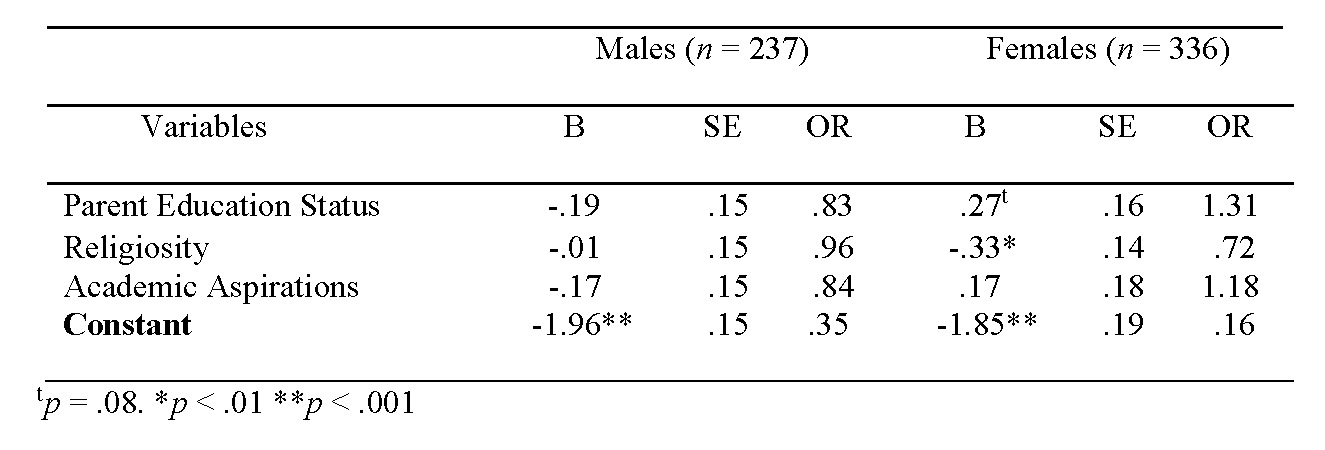

All variables were centered (with standardized scores). In the first model, demographic individual and family variables of age, gender, and parent education were entered first, with individual variables of religiosity, academic aspirations, self-esteem, and depression entered in the second model. In model three, the familial variables (family structure, family support, general communication, communication about sex) were entered, followed by neighborhood connectedness and school connectedness in a fourth step. The interaction terms between gender and all the variables were entered last to test for gender differences in associations of predictors with the outcome. Follow-up of significant interactions involved logistic regressions within gender (see Table 3).

The findings indicated an overall significant model fit in the final model, X2 (25, N = 539) 53.95, p < .001; the -2 log likelihood was 463.14. As may be seen in Table 2, which provides the results when all models were included in the analysis, the demographic variables of gender and age were significantly associated with initiation to first sex. As expected, boys (B = -.28, OR = .76, p < .05) and older adolescents (B = .48, OR = 1.62, p < .001) were more likely to initiate intercourse.

Results of Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis one predicted that individual factors would be associated with sexual initiation. There was mixed support for this hypothesis. Religiosity, academic aspiration, and self-esteem scores were not significantly related to sexual initiation. As expected, higher depression scores were significantly associated with sexual initiation. Hypothesis two, that adolescents exposed to lower parental communication and parental communication about sex would be more likely to initiate first sex, was not supported. But, as predicted, adolescents in non-two-parent families were more likely to initiate sex. Parent education did not have a direct effect on sexual debut. Hypotheses three and four tested whether adolescents exposed to lower neighborhood connectedness and school connectedness would be more likely to initiate first sex. Contrary to expectations, these community-based hypotheses were not supported. Overall, support for the hypotheses was provided by those who were older, male, had higher depression, and had non-two-parent family structure. These characteristics were all related to higher risk for initiating first sex.

This study also included tests of moderation. More specifically, hypothesis five predicted that gender would moderate the association among predictors and the outcome of sexual initiation. The association of familial connections, individual factors, and community factors were expected to have greater association with outcomes among girls than boys. This hypothesis was partially supported in that there were moderating effects of gender on associations of religiosity, parent education, and academic aspirations with sexual initiation. With respect to religiosity, the interaction effect (B = -.29, OR = .75, p < .05) was significant. As follow-up, separate analyses within gender were conducted (see Table 3) in order to examine gender differences among sexual initiation. As predicted, among girls, the first sex initiation was significantly less likely when religiosity (B = -.33, OR = .72, p < .01) was higher, whereas there was no significant association for boys (B = -.01, OR = .96, ns). Second, gender was a significant moderator for parent education status and sexual initiation. Follow up analyses indicated that higher parent education was more strongly associated with sexual debut among girls (B = .27, OR = 1.31, p < .08) than boys (B = -.19, OR = .83, ns).

Third, gender moderated the association between academic aspirations and sexual initiation (B = .23, OR = 1.26, p =.07). However, follow-up analyses between academic aspiration and sexual initiation showed no significant differences from zero for either boys or girls. The association was negative for boys (B = -.17, OR = .84) and positive for girls (B = .17, OR = 1.18). Contrary to expectations, gender did not moderate the associations of other variables with sexual initiation.

Discussion

The study used DiClemente et al.’s (2005) socio-ecological model as a framework for examining individual, family, and community factors related to African American adolescents initiation to first sex. All adolescents included in the study indicated that they had not had sex at Wave I. By Wave II, 21% indicated that they had experienced sexual initiation, that is, had first sex. As with previous research, the study found that demographic factors, such as age, gender, and family structure of participants, were related to sexual initiation (Luster & Small, 1994; Majumdar, 2005). Consistent with prior research, boys were more likely to have had sex than girls, and older adolescents were more likely to initiate into sexual intercourse than younger adolescents (Luster & Small, 1994; Mandara, Murray, & Bangi, 2003). Researchers have attributed a greater likelihood for boys to engage in sexual intercourse possibly due to less parental supervision (Mandara et al., 2003). Adolescents living with both parents were less likely to report first sex than adolescents in other family structures. These findings are consistent with Murry (1996) who found that African American adolescents who lived in two-parent households were more likely to delay age at first sex until 18 years of age and beyond. In another study involving eighth grade students, Boislard and Poulin (2011) reported that adolescents who were not in a two-parent family were engaged in earlier intercourse and problem behaviors. Our study did not differentiate between adolescents who were in adoptive two-parent families from those in biological two-parent families. Future studies should consider adoptive children (Grotevant, Ross, Marchel, & McRoy, 1999) and their sexual initiation outcomes. Given the higher rates of single parent families among Black families (Vespa, Lewis & Kreider, 2013), the impact of having two parents or not should be considered when designing programs for Black adolescents. How do single-parent families generate the resources and supervision thought to benefit the children who live in two-parent families? What strengths are present in single-parent families where the children delay sexual debut?

Only partial support was found for the two individual factors examined in this study. Consistent with the literature, greater religiosity was protective against sexual initiation, specifically for girls (Meier, 2003). Having strong religious beliefs may function as a social control mechanism for African American adolescent girls. Only two items measured academic aspiration. They were both related to whether the adolescent expected to go to college. Perhaps also considering their current GPA as well as their academic self-efficacy would have strengthened this measure (Ramirez-Valles, Zimmerman, & Juarez, 2002). The interaction with gender suggested that academic aspirations operated differently for the boys (lower odds) and girls (higher odds), but neither coefficient was significantly different from zero.

In the overall model, depression had a significant direct effect in the predicted direction. For depressive symptoms, McLeod and Knight (2010) found, that among adolescents who initiated sex by age 15, higher levels of depression were observed compared to adolescents who did not initiate by age 15. This study’s results were similar in documenting the association of prior depression with sexual initiation. The findings on depression suggest that lowering depression would be an important consideration for lowering the odds of early sexual initiation among African American adolescents.

Contrary to previous research, self-esteem was not significant in the final model. Longmore and colleagues (2004) found that higher self-esteem was associated with sexual debut at older ages for boys and, that compared to Black girls, depressive symptoms had a weaker effect. Using all ethnicities and all ages in the Add Health data (public version), Wheeler (2010) reported that higher self-esteem did not predict sexual debut for virgins one year later. It is possible that an association between self-esteem and depression (r = -.32, p < .001) may have meant that depression accounted for the variance in initiation to first sex, leaving less variance for associations between self-esteem and first sex. If so, then including both variables in this study adds important information that studying each variable alone does not provide. Contrary to expectations, the family relationship variables examined were not significantly associated with initiation into first sex. The effect of communication about sex was nonsignificant. Previous studies have found that good lines of communication with parents (Roche, Mekos, & Alexander, 2005) were associated with a delay in sexual intercourse. However, Davis and Friel (2001) reported a positive relationship between communication about sex and early sexual initiation. By using a sample of virgins at Wave I, this study aimed to clarify these discrepant findings. For example, literature reporting no association between conversation about sex and sexual initiation may demonstrate the futility of conversations after initiation has occurred (Davis & Friel, 2001). Earlier cross-sectional results on parent-child communication appear to be better explained as reactive rather than preventive. Other factors not studied that may be associated with a delay in sexual initiation include peer relationships (Kinsman, Romer, Furstenberg, & Schwarz, 1998). Also, the frequency of communication about sex was assessed, but not the level of reciprocity and quality of the communication between adolescents and their parents. Only parents reported on communication about sex. It is possible that parents’ rating of communication may be incongruent with adolescents’ reports that were not available. Other factors such as parental knowledge and comfort about discussing issues pertaining to sex might help to explain such findings (McNeely et al., 2002).

General communication about sex was not related to first sex. The variable measured communication about life issues and may not reflect association with adolescents’ decision to initiate sex. Contrary to expectations, family support was not significantly related to initiation of first sex. De Graaf et al. (2012) reported that family cohesion was associated with a delay in sexual intercourse. Studies by Kalina et al. (2013) and Longmore et al. (2001) indicated that parental monitoring had a stronger impact on delaying intercourse than parental or family support. Going forward, extending the study to parental monitoring measures may be important to more fully understand the effects of family variables on the odds of sexual initiation.

The community connections were not significant for this age group as well. Although studies have found that feeling connected to school and neighborhood may be beneficial for adolescents (Browning et al., 2004; McNeely et al., 2002), with this sample, they were not significant. A possible explanation for this contradictory finding is that these factors may not be salient in early adolescence because familial ties and peer relationships may be valued more in this age group (Steinberg et al., 1994).

This study used gender as a moderator between study variables and initiation to sex. Gender moderated the relationship between religiosity and sexual initiation. Having high religiosity was more protective for girls than it was for boys. Although academic aspiration was not a main effect, and the within-gender associations were not significantly different from zero, the significant interaction results indicated that having higher academic aspirations among boys was somewhat more protective but lower aspirations were a risk factor for early sexual initiation. Among girls the opposite pattern was seen. Such a pattern presents concerns if high aspiring girls are engaging more in first sex, possibly diminishing future success. Perhaps high aspiring girls are more likely to have romantic relationships that could include initiation to first sex. Future research will be useful in explaining the different directions of association for boys and girls.

Prevention strategies should focus on boys with low academic aspirations. More specifically, it might be beneficial if boys with lower academic aspirations are provided with mentors or other resources to increase their academic aspirations. Frisco (2008) found that academic goals were protective against sexual initiation, thus, increasing academic aspirations in boys may result in delayed first intercourse. But the recommendations for low aspiring girls would need to take into account their already somewhat lower likelihood of first sex initiation compared to low aspiring boys or higher aspiring girls. If the interaction by gender found in this study is replicated and follow-up results are similar, then prevention efforts would need to focus on these different patterns for boys and girls.

The study confirms some of the previous research. More specifically, religiosity, academic aspirations, self-esteem, depression, and adolescent age are important considerations either alone or in interactions with gender. Given the protective nature of religiosity in this study, particularly for girls, programs aimed at preventing African American adolescents from early sexual initiation could include church groups and settings. Whether it is having parents who encourage children to engage in religious activities or the activities themselves, parents could be encouraged to have their adolescents participate in religious activities. Adolescent’s gender is another important consideration. Efforts at prevention or intervention should consider what works best for boys and girls individually. Factors such as higher academic aspiration may be a greater deterrent for boys than for girls, whereas religiousness was a greater deterrent for girls.

The socio-ecological model was used to guide this research (DiClemente et al., 2005). In support of this theory, gender interacted with academic aspiration, religiosity, and parental education as predictors of sexual initiation. These findings suggest that boys’ and girls’ behavior is at least partially, but differentially, associated with individual characteristics. Other ecological factors that should be examined to advance understanding of African American adolescents’ initiation to first sex include parental monitoring and relationships with romantic partners. Nonetheless, the design of the study helped to address some of the methodological limitations of prior research. First, the sample was drawn from a national data set, which included a large sample of African American adolescents. Data from the CDC and other empirical studies indicate that African Americans have higher rates of teen pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections and diseases, as well as earlier onset of sexual intercourse than any other U.S. ethnic group. Despite a nationwide decrease in early adolescent sex, African American adolescents still have disproportionately higher rates than other ethnic groups. In 1995, 24% of African American adolescents reported having intercourse by age 13 and 73% of high school students reported being currently sexual active; compared to Whites among whom only 5% reported sex by age 13 and 49% of high school students reported being sexual active (CDC, 2007). The 2009 report indicated that 15% of African American adolescents reported intercourse by age 13 compared to 3.4% for Whites reporting sex by 13. Overall, 65% of African American high school students reported being sexually active compared to 42% of Whites (CDC, 2010). Thus, looking at a within ethnic group analysis of early to middle adolescents in a group with higher percentages of at-risk sexual behavior was an important strength of the study.

As a third strength of the study, data were collected from both parents and adolescents. Information about education level and communication about sex was collected from parents whereas information about sexual behavior and individual, family, and community connections were collected from the adolescents. Because this dataset included African American families from all economic strata, it is instructive that parental education was related to adolescent’s sexual initiation. More specifically, higher education of parents was associated with lower likelihood of initiation of sex for girls. Nonetheless, other demographic variables might have been considered, such as whether parents of adolescents were themselves teen parents. A fourth strength of this investigation was the use of virgins at time one to examine initiation to intercourse 12 months later, thus controlling for the temporal order of effects. Finally, this research used a multivariate design whereby all study predictors were entered in hierarchical groupings of variables. This design provided greater control for shared variance effects and reduced the likelihood of providing significant findings for variables that might be significant only when tested alone.

There are limitations to this study. First, the study was based on secondary data; therefore, only available items were used to create scales. These items may not necessarily have been the best measure of the constructs identified in the literature and theory. Perhaps a greater limitation of the study was the use of dichotomous items to measure general communication and neighborhood connectedness. Information is lost when variables are measured in such a restrictive manner. Although a longitudinal design constitutes strength of the study, it is also subject to loss of participants through attrition. However, analyses revealed primarily nonsignificant differences between the participants who were in the study at Wave I, and who did not return at Wave II. Furthermore, those not returning (boys, younger, higher parent education) shared only one characteristic associated in the literature with higher risk of sexual initiation of first sex (being male). Another limitation of the study was that differences across sexual orientation were not examined. Initiation into first sex was used as the outcome regardless of the sexual orientation of the adolescent. Research documents lower school performance and higher depression among Dutch early adolescents with same sex attraction (Bos, Sandfort, de Bruyn, & Hakvoort, 2008). As well, Jager and Davis-Kean (2011) note the complexity of coding in the Add Health where participants reported being heterosexual but having same-sex attractions. Future studies should consider differences across sexual orientation. Another weakness is that the data was initially collected over 20 years ago and may not fully reflect the views and behaviors of adolescents today.

Future studies should seek to examine in detail the role that romantic partners and peers play in adolescent sexual decision-making and sexual initiation. Because parental influence tends to decline as adolescents age (Steinberg & Silk 2002) and sexual intercourse may be a “normative” behavior in later adolescence, romantic partners and peers may have greater influence on adolescents’ later sexual behavior.

In sum, this study was conducted to examine individual characteristics, familial factors, and community connections as predictors of African American adolescent sexual initiation. Partial support was found for the study hypotheses. Notably, gender, parent education, religiosity, depression, and academic aspirations were associated with the initiation to sexual intercourse as either direct effects or in interaction with gender. Including multiple variables in one longitudinal national study clarified that these predictors of African American sexual debut were present regardless of the presence of other possible predictors.

References

- Boislard P., M., & Poulin, F. (2011). Individual, familial, friends-related and contextual predictors of early sexual intercourse. Journal of Adolescence, 34(2), 289-300. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.002

- Bearman, P. S, & Bruckner, H. (2001). Promising the future: Virginity pledges and first intercourse. American Journal of Sociology, 106, 859–912.

- Bos, H. W., Sandfort, T. M., de Bruyn, E. H., & Hakvoort, E. M. (2008). Same-sex attraction, social relationships, psychosocial functioning, and school performance in early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 59-68. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.59

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues (pp. 185-246). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Brooke, J. S., Balka, E. B., Abernathy, T., & Hamburg, B. A. (1994). Sequence of sexual behavior and its relationship to other problem behaviors in African American and Puerto Rican adolescents. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 155,107–114.

- Browning, R. C., Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2004). Neighborhood context and racial differences in early adolescent sexual activity. Demography, 41, 697-720. doi:10.1353/dem.2004.0029.

- Buhi, E. R. & Goodson, P. (2007). Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: A theory guided systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 4-21.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR CDC Surveillance Summaries 2007; 55 (SS-05). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2014). 1991-2013 High school youth risk behavior survey data. Available at http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/.

- Costa, F. M., Jessor, R., Donovan, J. E., & Fortenberry, J. D. (1995). Early initiation of sexual intercourse: The influence of psychosocial unconventionality. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 5, 93-121

- Davis, E., & Friel, L. (2001). Adolescent sexuality: Disentangling the effects of family structure and family context. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 63(3), 669-681. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00669.x.

- de Graaf, H., van de Schoot, R., Woertman, L., Hawk, S. T., & Meeus, W. (2012). Family cohesion and romantic and sexual initiation: A three wave longitudinal study. Journal of Youth And Adolescence, 41(5), 583-592. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9708-9

- Danso, K. (2014). Neighborhood social capital and the Health and health risk behavior of adolescent immigrants and non-immigrants. Unpublished Dissertation. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/2KGQOPK

- DiClemente, R. J., Salazar, L. F., Crosby, R. A., & Rosenthal, S. L. (2005). Prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents: the importance of a socio-ecological perspective—a commentary. Public Health (Elsevier), 119(9), 825-836. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2004.10.015

- Dryfoos, J. G. (1990). Adolescents at risk: Prevalence and prevention. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Ethier, K. A., Kershaw, T. S., Lewis, J. B., Milan, S., Niccolai, L. M., & Ickovics, J. R. (2006). Selfesteem, emotional distress and sexual behavior among adolescent females: Inter-relationships and temporal effects. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(3), 268-274. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.12.010

- Frederick, H. (2008). Predictors of risky sexual behaviors among African American adolescents. Unpublished Thesis. Texas Tech University, Lubbock Texas.

- Frisco, M. L. (2008). Adolescents’ sexual behavior and academic attainment. Sociology of Education 81, 284-311.

- Grotevant, H. D., Ross, N. M., Marchel, M. A., & McRoy, R. G. (1999). Adaptive behavior in adopted children: Predictors from early risk, collaboration in relationships within the adoptive kinship network, and openness arrangements. Journal of Adolescent Research, 14(2), 231-247. doi:10.1177/0743558499142005.

- Hallfors, D., Waller, M. W., Bauer, D, Ford, C. A., & Halpern, C. T. (2005). Which comes first in adolescence - Sex and drugs, or depression? American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 29(3), 163-170.

- Harris, K. M., Duncan, G. J., & Boisjoly, J. (2002). Evaluating the role of ‘Nothing to Lose’ attitudes on risky behavior in adolescence. Social Forces, 80(3), 1005-1039.

- Harris, K. M., Florey, F., Tabor, J., Bearman, P. S., Jones J., & Udry, J. R. (2003). The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: Research design. Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Honora, D. (2002). The relationship of gender and achievement to future outlook among African American adolescents. Adolescence, 37(146), 301-316.

- Hutchinson, M. K. (2002). The influence of sexual risk communication between parents and daughters on sexual risk behaviors. Family Relations, 51(3), 238–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00238.x.

- Jager, J., & Davis-Kean, P. (2011). Same-sex sexuality and adolescent psychological well-being: The influence of sexual orientation, early reports of same-sex attraction, and gender. Self and Identity, 10(4), 417-444. doi:10.1080/15298861003771155

- Jessor, R. (1991). Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12, 597-605.

- Jordahl, T., & Lohman, B. J. (2009). A bioecological analysis of risk and protective factors associated with early sexual intercourse of young adolescents, Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 1272-1282. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.05.014.

- Kalina, O., Geckova, A. M., Klein, D., Jarcuska, P., Orosova, O., van Dijk, J. P., & Reijneveld, S. A. (2013). Mother’s and father’s monitoring is more important than parental social support regarding sexual risk behaviour among 15-year-old adolescents. European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 18(2), 95-103. doi:10.3109/13625187.2012.752450

- Kinsman, S. B., Romer, D., Furstenberg, F. F., & Schwarz, D. F. (1998). Early sexual initiation: The role of peer norms. Pediatrics, 102, 1185-1192.

- Kotchick, B.A., Shaffer, A., Forehead, R., & Miller, K.S. (2001). Adolescent sexual behavior: Multi system perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 493-519. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00070-7.

- Lefkowitz, E., Romo, L., Corona, R., Au, T., & Sigman, M. (2000). How Latino American and European American adolescents discuss conflicts, sexuality, and AIDS with their mothers. Developmental Psychology, 36(3), 315-325. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.3.315.

- Loeber, R., & Dishion, T.J. (1983). Early predictors of male delinquency: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 94, 68-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.94.1.68.

- Longmore, M. A., Manning, W. D., Giordano, P. C., & Rudolph, J. L. (2004). Self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and adolescents’ sexual onset. Social Psychology Quarterly, 67(3), 279-295. doi:10.1177/019027250406700304

- Longmore, M. A., Manning, W. D., & Giordano, P. C. (2001). Preadolescent parenting strategies and teens’ dating and sexual initiation: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 322-335. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00322.x

- Luster, T., & Small, S.A. (1994). Factors associated with sexual risk taking behaviors among adolescents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 622-632. doi: 10.2307/352873.

- Lynam, D. R., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Wikström, P. H., Loeber, R., & Novak, S. (2000). The interaction between impulsivity and neighborhood context on offending: The effects of impulsivity are stronger in poorer neighborhoods. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,109, 563-574.

- Majumdar, D. (2005). Explaining adolescent sexual risks by race and ethnicity: importance of individual, familial, and extra familial factors. International Journal of Sociology of the Family, 31, 19–37.

- Markham, C., Lormand, D., Gloppen, K., Peskin, M., Flores, B., Low, B., & House, L. D. (2010). Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46, 23-41. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.214.

- Mandara, J., Murray, C.B., & Bangi, A. K. (2003). Predictors of African American sexuality: an ecological framework. Journal of Black Psychology, 29, 337- 356.

- Manlove, J. S, Terry- Humen, E., Ikramullah, E. N., & Moore, K. A. (2006). The role of parent religiosity in teens transitions to sex and contraception. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 578-587. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.008.

- McLeod, J. D., & Knight, S. (2010). The association of socioemotional problems with early sexual initiation. Perspectives on Sexual & Reproductive Health, 42(2), 93-101. doi:10.1363/4209310

- McNeely, C., & Falci, C. (2004). School connectedness and transition into and out of health risk behavior among adolescents: A comparison of social belonging and teacher support. Journal of School Health, 74, 284-292. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.

- McNeely, C., Shew, M. L., Beuhring, T., Sieving, R., Miller, B. C., & Blum, R. W. M. (2002). Mothers’ influence on the timing of first sex among 14- and 15-year-olds. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(3), 256-265. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X%2802%2900350-6

- Meier, A. M. (2003). Adolescents’ transitions to first intercourse, religiosity, and attitudes about first sex. Social Forces, 81, 1031-1052. doi:10.1353/sof.2003.0039.

- Meschke, L., Zweig, J., Barber, B., & Eccles, J. (2000). Demographic, biological, psychological, and social predictors of the timing of first intercourse. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 10(3), 315-338. doi:10.1207/SJRA1003_5.

- Miller, B. C., Norton, M. C., Curtis, T., Hill, E. J., Schvaneveldt, P., & Young, M. H. (1997). The timing of sexual intercourse among adolescents: Family, peer, and other antecedents. Youth & Society, 29(1), 54-83. doi:10.1177/0044118X97029001003

- Millstein, S. G. (2003). Risk perception: Construct development, links to theory, correlates and manifestations. In: D. Romer (Ed.) Reducing adolescent risk: Towards an integrated approach (pp. 35-43). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishers.

- Mitchell, C. M., Whitesell, N. R., Spicer, P., Beals, J., & Kaufman, C. E. (2007). Cumulative risk for early sexual initiation among American Indian youth: A discrete-time survival analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 387-412. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00527.

- Moore, M., & Chase-Lansdale, P. L. (2001). Sexual intercourse and pregnancy among African American girls in high poverty neighborhoods: the role of family and perceived community environment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1146-1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01146.x.

- Moore, S., & Rosenthal, D. (1993). Sexuality in adolescence. New York: Routledge.

- Murry, V. (1996). An ecological analysis of coital timing among middle-class African American adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Research,11, 261-279. doi:1177/0743554896112006

- Paul, C., Fitzjohn, J., Herbison, P., & Dickson, N. (2000). The determinants of sexual intercourse before age 16. Journal Adolescent Health, 27, 136-147. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00095-6.

- Ornelas, I. J., Perreira, K. M., & Ayala, G. X. (2007). Parental influences on adolescent physical activity: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity, 4, 1-10. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-4-3.

- Radloff, L.S (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385-401.