Gender, Sexual Identity, and Families: The Personal Is Political

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Chapter 2: After DOMA: Same-Sex Couples and the Shifting Road to Equality

Introduction

On June 26, 2013, the United States Supreme Court ruled that Section Three of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which defined marriage as between a man and a woman, was unconstitutional (Freedom to Marry, 2013; Human Rights Campaign, 2013; Reilly & Siddiqui, 2013). Section Three of the Defense of Marriage Act defined marriage as being between a man and a woman only, and prevented the federal government from acknowledging any same-sex marriages for the purpose of federal programs or laws, even those recognized by states (GLAAD, 2013). Under DOMA, married gay and lesbian couples were denied important protections and rights, such as social security benefits, family and medical leave, the ability to pool resources without heightened taxation, military family benefits, and hospital visitation rights (Andryszewski, 2008; Freedom to Marry, 2013; GLAAD, 2013; Goldberg, 2009; Mathy & Lehmann, 2004). Thus, the Supreme Court’s decision upheld that all married couples deserve equal treatment and respect under the law, and marked the end of the denial of over 1,100 federal protections and benefits of marriage to same-sex couples (Drescher, 2012; Freedom to Marry, 2013; Human Rights Campaign, 2013; Killian, 2010; Mathy, Kerr, & Lehmann, 2004; Pelts, 2014; Steingass, 2012). These privileges of legal married status had previously been available to all other married people, and thus the repeal of Section Three of DOMA was a major victory for marriage equality in the United States (Barnes, 2013; Freedom to Marry, 2013; GLAAD, 2013; Human Rights Campaign, 2013; Reilly & Siddiqui, 2013). The purpose of this study was to capture the essence of the lived experiences of same-sex couples during this unique and fleeting time period, as a significant event in the marriage equality movement was taking effect

Literature Review

To date, the existing literature on the repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act is sparse, with most available studies (Aoun, 2016; Dominguez, 2015) focusing on other aspects of same-sex relationships and only including DOMA as one of many considerations. The exception to this is an article (Pelts, 2014) discussing the effects of the June 2013 ruling repealing DOMA. This article discussed the history and current state of same-sex marriage but did not include interviews with, or voices of, same-sex couples. However, a broader examination of literature related to same-sex marriage and DOMA may be helpful in orienting readers to this study.

The Supreme Court’s ruling came after nearly 17 years of DOMA being in effect, during which time Section Three had been hotly debated and ruled unconstitutional ten times at the district court, U.S. Bankruptcy Court, and U.S. Court of Appeals levels (Barnes, 2013; Drescher, 2012; Freedom to Marry, 2013; GLAAD, 2013; Human Rights Campaign, 2013; Reilly & Siddiqui, 2013; Rimmerman, 2008). The ruling took effect on July 21, 2013, 25 days after the decision was made (Freedom to Marry, 2013). Married same-sex couples living in 13 states and the District of Columbia, had their marriages federally sanctioned and were eligible for the same federal responsibilities and protections of marriage for the first time in U.S. history (Barnes, 2013; Freedom to Marry, 2013).

However, only Section Three had been ruled unconstitutional (Barnes, 2013; Freedom to Marry, 2013; GLAAD, 2013; Human Rights Campaign, 2013). The remaining significant section of DOMA, Section Two, maintained that individual states were not required to acknowledge the marriages of same-sex couples who were married in another state (Barnes, 2013; GLAAD, 2013; Freedom to Marry, 2013; Human Rights Campaign, 2013). Thus, couples living in states that did not recognize their marriages often had difficulty accessing federal marriage benefits (Freedom to Marry, 2013; Human Rights Campaign, 2013). Due to this inequality in state recognitions, the experiences of same-sex couples had the potential to be drastically different from one state to the next.

The differences did not end in the legal sphere, however. Several political figures spoke out in support of the Supreme Court’s decision, while others defended the Act: supporters insisted that it was morally correct, necessary to protect children, and biblically sanctioned (Barnes, 2013; Drescher, 2012; Reilly & Siddiqui, 2013; Rimmerman, 2008). This debate extended to all echelons of U.S. society—deliberations on the subject occurred across social media, periodicals, and websites of educational and political organizations. It was in this sociopolitical climate of heightened scrutiny and uncertainty that same-sex couples had to navigate their relationships and lives. The aim of this study was to explore the lived experiences of same-sex couples across the country, as well as to identify differences in experience based on states and related legal status.

Method

In order to best address the aims of this study, a mixed-method, convergent parallel design was utilized to attain complementary data on the topic (Morse, 1994). A data validation variant was used in order to allow the qualitative data to corroborate and elaborate upon the results of the quantitative data, as discussed by Creswell and Plano Clark (2011). Following approval by Nova Southeastern University’s IRB board, participants were recruited online via a social media site (Facebook); ads were placed on the Facebook pages of the Human Rights Campaign and PFLAG chapters, with permission obtained before posting. Interested participants followed a link to a 25-question survey comprised of open- and closed-ended questions. Survey methodology was used to obtain responses from people across the country, providing a more representative sample of the larger national LGB population than would be feasible via in-person interviewing methods.

Through the quantitative paradigm utilized in this study, the relationship between state of residence (and local marriage laws) and perceptions of Section Three’s repeal was sought and assessed. State of residence was divided between three domains: equal marriage protections and recognition; some protections and/or recognition; and no protections or recognition. This study attempted to ascertain a correlational relationship between variables only, as many confounding variables precluded assessing for a causal relationship, and further analysis was beyond the scope and intention of this study.

Through the qualitative methodology utilized in this study, participants were asked to describe their experiences related to the repeal. To remain as close as possible to the research participants’ words and truths following the Section Three repeal, the transcendental approach to phenomenology was used, which focuses more on participants’ descriptions of their experiences rather than on the researcher’s interpretations (Moustakas, 1994), was used. Following data collection, content areas present in both data sets were identified and transferred as needed to facilitate relating the two data types.

Participants

For this study, a sample size of 26 participants was utilized. This sample size is larger than a typical sample size for phenomenological studies, which generally include around 10 participants (Creswell, 1998), but smaller than a typical sample for quantitative studies, generally between 50-85 participants (Collins, Onwuegbuzie, & Jiao, 2007). This sample size was chosen in order to allow for the creation of a rich description of participants’ experiences; even if saturation was reached early on in the analysis, this provides added validity to the findings. Second, although many mixed-methods studies utilize separate samples for the quantitative and qualitative portions, this number allows for the utilization of the same sample for both, creating a more integrated and valid study. Participant demographics are available in Table 1. Thirty-one total people responded to the study, however, only those meeting study criteria (over the age of 18; residing in the United States, District of Columbia, or Puerto Rico; and self-identifying as being in a same-sex relationship for at least one year) were included in the analysis. Qualitative results will be discussed first, followed by quantitative results.

Results

Commonly Shared Experiences

Several experiences regarding the Section Three repeal were discussed by multiple participants. These experiences provide a glimpse into the lived experience of respondents and reveal the essence of this event. Four shared themes emerged: Marry or Not?, Support or Not?, Impact or Not?, and Progress or Not?

Marry or Not?

As DOMA and its Section Three both concern the definition of legal marriage in the United States, it is perhaps unsurprising that a central theme arising from participants was that involving marriage and their related decisions, or inability to make decisions. This theme was divided into the subthemes We Do!, Still Deciding, and Not Now.

We do! Participants within this theme had decided to get married, and most had already done so. Several indicated the importance of the repeal in giving them the ability to get married; one respondent stated that “We are [now] legally married in Washington because we were registered domestic partners. Our partnership turned into marriage. We are very happy.” Whereas many of these participants had gotten married in their own states, others had done so in others: a man from North Carolina indicated, “My state doesn’t allow same-sex marriage. We married in D.C. instead.”

Still deciding. The decision to get married was not as simple for some respondents as it was for others. People in this group had extenuating circumstances to consider, specifically, many had medical conditions that made marriage financially difficult. As one man explained, “For us, getting married might not be a good thing. One of us lives with AIDS, and being married would screw up his needs-based medical care.”

These responses indicated the high impact finances have on couples’ decisions to marry, not unlike in many heterosexual relationships. However, these also highlight the disproportionate burden and stigma placed on gay male couples by AIDS.

Not now. Other respondents indicated that marriage was not currently for them and their relationships. Many respondents indicated that they were simply not ready. One man living in Washington explained, “We have only been together for one and a half years - not yet ready to commit to a lifetime together. That said, we are very happy together and both believe marriage and children are possibilities for the future.” Another rationale was disagreement with marriage as an institution. An Oregon woman explained, “We have decided not to get married...we both think marriage is a capitalist institution that historically has been used as an excuse to keep women subjugated.”

Support or Not?

Respondents reported varying levels of support for their relationships. Support, as defined by participants in this category, fell under two subcategories. The first, Legal Support, involved legal benefits supporting same-sex couples after the repeal. These included benefits such as hospital visitation for a partner, the right to buy and own a home together, partner inclusion on work-provided insurance, and tax benefits. The second, Social Support, included support from families, friends, and communities.

Legal support. Only six of the twenty-six respondents reported legal support following the repeal, primarily in the form of sharing property and tax benefits. This low percentage could be seen as an indication of the newness of the extension of benefits to same-sex couples, the limited number of LGBTQ people who actually have access to these benefits, and work still needed to extend benefits to same-sex couples.

We’ve got benefits! Six respondents replied that they had received benefits as a result of the repeal, and indicated that these were very helpful. A male respondent from Wisconsin expressed, “Being able to share health insurance when we marry is huge. It will give us so much more flexibility and, honestly, a better, fairer quality of life.”

Still Fighting. The majority of respondents reported that they had not received benefits following the repeal, often because of respective state laws. Some reported increased discrimination following the repeal: A Colorado man explained,

Weirdly, my partner’s human resources department has become more hard-nosed against us since we don’t have legal status...Before there were legal options, they just quietly looked the other way in those situations.

These experiences support the literature regarding the backlash against LGBTQ groups following legal progress (Freedom to Marry, 2013).

Social support. Respondents reported levels of support from families, friends, and community members varied greatly. Many respondents indicated they had received positive social backing, others reported mixed support, and a few reported continued discrimination and a lack of social support.

Positive. Many respondents reported that family members, friends, and other people in their lives had been supportive. A man in Washington summed up the experiences of many participants, stating that significant others had been “All positive and supporting,” and a woman in Colorado revealed that “My community is very open and accepting and I feel blessed to have moved here.”

Mixed. Others reported mixed responses from significant others. Variations were often seen as unsurprising; as a Colorado man summarized, “Varied, of course!”

Negative. Despite the majority of respondents reporting positive reactions from social contacts, some respondents reported negative responses. Often, this came from acquaintances rather than close friends or family members: A Colorado man reported,

I do feel that the debate has caused some of the community who oppose marriage equality to increase their level of opposition. Only in the past few years have I really felt strongly discriminated against...prior to the current climate of debate about marriage equality they just pretty much left me alone.

Impact or not?

A major issue discussed by respondents was the impact of the repeal and related social responses on their individual and relationship well-being and functioning. Generally, participants felt that the repeal had positive effects on themselves and their relationships, but a few spoke of ways that it increased pressure on them. Responses in this category fell under two subcategories, Relationship Impacts and Individual Impacts.

Relationship impacts. Most of the impacts reported by respondents were related to their couple relationships. Responses within this theme were further divided into two subthemes, We’ve Been Affected, in which participants perceived relationship impacts from the repeal, and Still the Same, in which participants felt unaffected by the repeal.

We’ve been affected. One of the most commonly reported impacts was that of social support benefitting respondents’ couple relationships. A Wisconsin man wrote that the responses of family and friends had been “Nearly 100% positive and supportive. Their support and love has helped our relationship grow and mature.” Other respondents reported that the legal changes had positively impacted their relationships. A Wisconsin resident wrote that “I feel we have more of an opportunity for long term success as a couple by having some federal (and maybe state) recognition if we get married.” Finally, many reported feeling safer following the repeal. A New York man wrote, “Although we still are harassed for being gay and together it happens much less frequently.”

Unfortunately, not all effects were positive. Several respondents reported feeling increased pressure to get married. For example, a Wisconsin man felt that the repeal had

Actually made [our relationship status] a bit more insecure. We do not live together, and it’s caused questions of commitment to come up. Now that we can get married in certain states, will we? If not, what is our relationship all about and where is it leading? (emphasis in original).

Still the same. Although many respondents felt their relationships had been impacted by the repeal, others felt unaffected. A Colorado woman explained “Our relationship is rock solid. Increased legal and/or social recognition is just the icing on the cake. We deserve equality and are glad it is happening but did not expect to see it in my lifetime.”

Individual impacts. Most respondents reported that impacts of the repeal were primarily on their relationships rather than on them personally. However, as the law targeted the LGBTQ population, some respondents felt individual impacts. This subcategory was separated into the themes I’ve Been Affected and Still the Same.

I’ve been affected. Respondents discussing this theme spoke of feeling safer following the repeal, this time in an individual sense. A Wisconsin man explained, “I’m happy that opinions are changing, it makes me feel safer, physically and emotionally.”

Still the same. Other respondents felt that the repeal and related social responses hadn’t impacted them as an individual. A North Carolina resident explained that “My other family members haven’t said much about the issue, but that’s okay with me, because I’ve learned to not need their support so much. I continue on with my life anyway.”

Progress or not?

Overall assessment. In the final category, participants gave their overall opinions of the repeal. Views of the repeal were solidly positive, labeling the repeal as a major event in the movement for LGBTQ rights and the morally right decision. This theme was divided into four subthemes: Major Event, Right Decision, About Time, and Next Steps.

Major event. Many participants felt that the repeal was an important, even historical, event. One man from New York elaborated, “It is a major domino falling that signifies the beginning of the downfall to marriage inequality throughout the country.” Another man from Colorado went beyond the repeal’s immediate implications: “I feel the repeal has meaning far beyond marriage and deals more with basic human dignity.”

Right decision. Many participants also spoke of the repeal in an ethical context, expressing their feelings that the right decision had been made. As a New York man stated, “It was the right decision, morally and legally.”

About time! Several made statements to the effect that it was “high time” for the repeal. This theme was highly saturated in the data, with several respondents using the phrase, “it’s about time” or “it was about time” to describe their feelings about the repeal.

Next steps. Although participants were nearly unanimous in their feelings that the repeal was a significant step forward for marriage equality, they also felt there was more to be done. Some stressed the importance of societal education and acceptance: a New York man wrote, “It will be a long time before it is accepted throughout the nation in more than a legal sense.” Respondents also discussed the importance of changing other laws to reach true equality for same sex couples. An Oregon resident discussed hopes that

Maybe some of the groups listed above (LGBTQ) as well as the money going towards these groups will now hopefully be used to address bigger issues in the community, like homelessness, access to healthcare, violence perpetrated against Trans individuals particularly Trans women of color. There are so many things that need attention and this marriage crap is taking all center stage when it’s not the most pressing issue to be fighting.

State Comparisons

In addition to the themes found across all respondents, several themes specific to geographic legal groups emerged. Responses were divided into three categories:

- Respondents living in states with constitutional bans (Arizona, North Carolina) (n = 3)

- Respondents living in states without full legal marriage but some rights (Colorado, Florida, Michigan, Texas, and Wisconsin) (n = 17)

- States with legal same-sex marriage (Connecticut, New York, Oregon, and Washington) (n = 6)

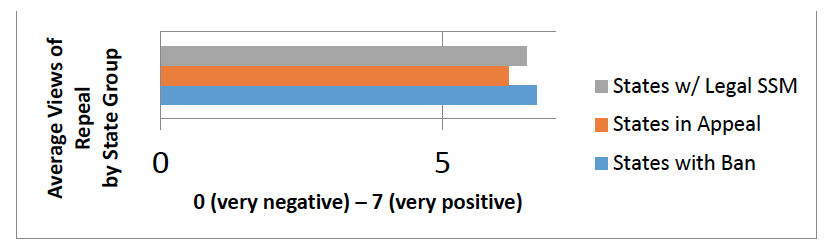

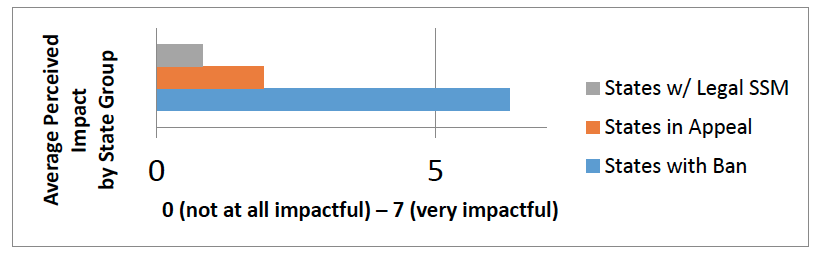

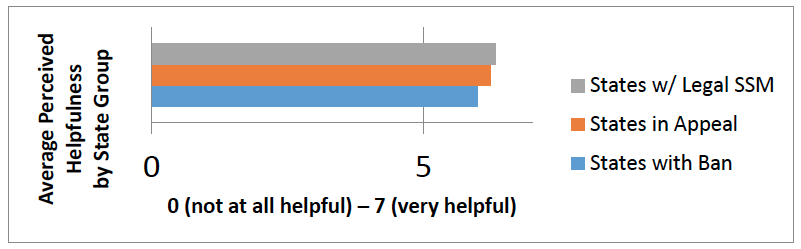

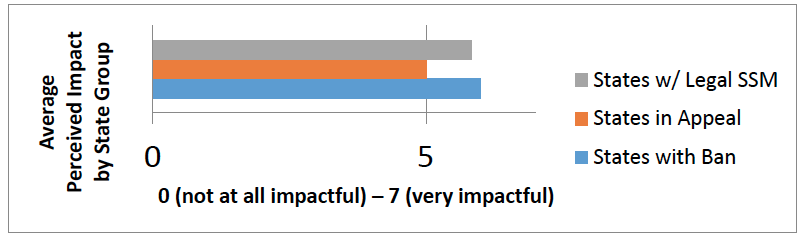

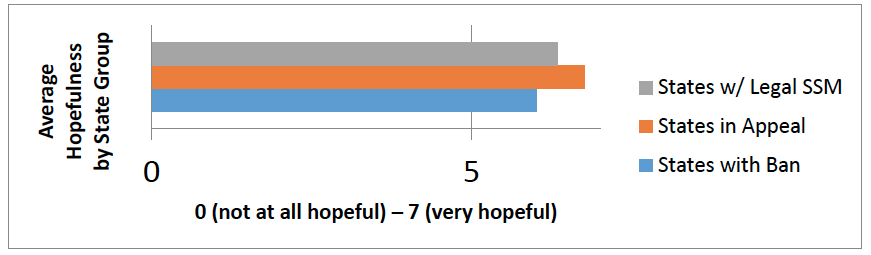

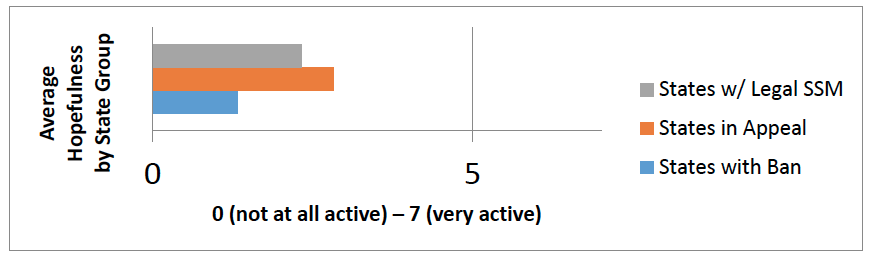

Survey responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics and a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test, as a more complex analysis was beyond the intent and scope of the study, and was precluded by small response rates in some groups. Although most differences were not statistically significant, distinct themes within groups and differences between groups were identified. For visual representations of state differences, refer to Figures 1- 7.

Participants in States with Legal Same-Sex Marriage. This group of respondents had state recognition of their marriages prior to the repeal; however, these marriages were being federally recognized for the first time. They tended to live in more socially progressive areas; their relationships were more supported than other groups’ and generally were not seen as “a big deal”, as an Oregon respondent put it.

Respondents in states with legal same-sex marriage gave written responses reflecting a higher level of relationship freedoms and choices than the other groups. This group contained more married respondents than the other groups; as well as the only participant who indicated an active choice not to get married, rather than deciding due to financial or legal barriers or not feeling ready. Additionally, respondents in this group discussed “moving forward” following the repeal more than the other groups.

Participants in States with Rulings for Same-Sex Marriage Currently in Appeals. These respondents were living in rapidly changing political and social climates. Although their states had struck down bans on, or ruled for legalization of, same-sex marriage, all had subsequently seen appeals on these laws, leaving same-sex couples residing in those states in legal limbo. Many of these states were undergoing legal proceedings, increased advocacy efforts, and increased protests of same-sex marriage.

State Differences

(Statistically significant differences denoted by *)

Respondents in this group showed higher levels of frustration with the legal proceedings, social debates, and instability involving their relationships and legal standing in their written responses. They reported higher levels of political action than the other groups, as well as high levels of optimism for future change. Reflected in the statistical analyses, respondents in this group appeared less vulnerable to changes in legal and social climate in that they reported the least impact of the change in law, perhaps because appeals put their status in limbo in these states. Furthermore, in their written responses, they comprised all reports of increased social discrimination post-repeal. This group also reported more shifts in their couple relationships following the shifts in social and legal contexts.

Participants in States with Constitutional Bans on Same-Sex Marriage. Respondents in this group lived in areas in which their relationships were devalued and often openly discriminated against, based on written comments. They had fewer legal rights and protections than respondents from other states, and some had no options for state-recognized unions. These state laws were often mirrored, and fueled, by local public opinion. These conditions provide a context for participant responses from this group of states.

Respondents living in states with constitutional bans gave written responses indicating resiliency and finding ways to thrive despite the lack of state support. They also showed high levels of optimism for eventual marriage equality, despite their current legal situation. However, their written responses indicated higher levels of vulnerability to legal and social situations and reported finding comfort in the new federal benefits extended to them.

In terms of statistically significant differences between groups, participants in states with constitutional bans reported experiencing more impacts on their lives and couple relationships than couples in the other two groups. Additionally, participants differed in their levels of activity in LGBTQ rights advocacy. Specifically, participants living in states with rulings for same-sex marriage in appeals showed significantly higher levels of advocacy than both of the other groups, whereas participants in states with bans against same-sex marriage reported lower levels of activeness than the other groups. Other differences were not statistically significant.

Discussion

In combining the results of the qualitative and quantitative analysis, several patterns in participants’ responses were elucidated. First, both qualitative and quantitative results revealed that overall, participants across groups viewed the Section Three repeal as a positive and important event. Furthermore, participants in all states reported beliefs that the repeal would be helpful in providing same-sex couples access to the privileges and benefits of marriage, as well as supporting the marriage equality movement. Finally, very few participants in any group had received any benefits following the repeal, indicating that more must be done to attain full marriage equality in the United States.

In addition, results highlighted important differences between groups. Despite minimal findings of statistical significance between groups, both qualitative and quantitative results indicated that participants in states with bans on same-sex marriage felt that legal status and social opinion had more impact on their couple relationships than did participants in other states. Further, although very few participants in any group reported receiving benefits following the repeal, based on their written commentary to the questions, participants in states with bans on same-sex marriage reported the fewest received benefits, and also indicated these benefits were more helpful to them than did other groups. This finding highlights an important discrepancy between need and actual support provided to participants in states with bans. Additionally, participants in states undergoing appeals processes regarding same-sex marriage reported significantly higher levels of advocacy in LGBTQ rights advocacy, which may suggest a connection between legal processes and advocacy efforts.

The narratives of this study indicate that the repeal was an important event for LGBTQ rights, with far-reaching implications for marriage and human rights within the United States. However, these narratives also reveal that the fight for marriage equality was not over; that there was still much to be done. The subsequent Supreme Court ruling on June 26, 2015 struck down Section Two of DOMA and thus established nationwide marriage equality, regardless of previous state laws (Liptak, 2016). However, many states responded to the 2013 and 2015 repeals by introducing bills allowing religious exemptions for providing service to LGBTQ clients, restricting adoption by same-sex couples, and allowing for the refusal to grant marriage licenses (ACLU.org, 2017; Blinder & Perez-Pena, 2015; Harris, 2017; Pizer, 2016). Follow-up research would be helpful in assessing the ongoing state of same-sex couples. This may be especially pertinent considering the rarity of participants in this study receiving benefits they were purported to get post-repeal. According to phenomenological theory, the truth of history lies in the experiences of those most intimately connected to the event. It is therefore our role as couple and family researchers and therapists to listen and to assist where we are able.

Limitations of the Study

Study participants were predominantly male, cisgender, Caucasian, and identified as gay; therefore, results may not apply to all LGBTQ individuals. Second, although Facebook is a popular social media site, particularly in the LGBTQ community, the study was limited to people who were literate and had computer access and Facebook accounts. Other social media sites (e.g., Instagram, Twitter) were not utilized, which may systematically impact the sample. The numbers of people in the state category analyses were very small in some groups. This means that the power to detect differences was low; larger sample sizes in the state categories might have identified differences. Overall, the findings of this study represent the experiences of study participants, and cannot be generalized to all same-sex couples post-repeal. Additional research would contribute valuable information and understanding of the experiences of same-sex couples following the repeal of DOMA’s Section Three.

References

- American Civil Liberties Union. (2017). Past anti-LGBT religious exemption legislation across the country. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/other/past-anti-lgbt-religious-exemption-legislation-across-country

- Andryszewski, T. (2008). Same-sex marriage: Moral wrong or civil right? Minneapolis, MN: Twenty-First Century Books.

- Aoun, A. R. (2016). The immigration challenges of same-sex binational couples and the impact on relationships, mental health, and well-being. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest dissertations and theses. (AAI3663196)

- Barnes, R. (June 26, 2013). At Supreme Court, victories for gay marriage. Retrieved from http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2013-06-26/politics/40195683_1_gaycouples-edith —windsor-doma

- Blinder, A., & Perez-Pena, R. (2015, September 1). Kentucky clerk denies same-sex marriage licenses, defying court. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/02/us/same-sex-marriage-kentucky-kim-davis.html

- Collins, K. M. T., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Jiao, Q. G. (2007). A mixed methods investigation of mixed methods sampling designs in social and health science research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(3), 267-294.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Dominguez, D. G. (2015). DOMA’s demise: A victory for non-heterosexual binational families. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest dissertations and theses. (AAI3581795)

- Drescher, J. (2012). The removal of homosexuality from the DSM: Its impact on today’s marriage equality debate. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health, 16(2), 124-135.

- Freedom to Marry. (2013). The defense of marriage act. Retrieved from http://www.freedomtomarry.org/states/entry/c/doma

- Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD). (July 2013). Frequently asked questions: Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). Retrieved from http://www.glaad.org/marriage/doma

- Goldberg, A. (2009). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual family psychology: A systemic, lifecycle perspective. In J. H. Bray & M. Stanton (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of family psychology. (576-587). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Harris, E. A. (2017, June 20). Same-sex parents still face legal complications. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/20/us/gay-pride-lgbtq-same-sex-parents.html

- Human Rights Campaign. (July 30, 2013). Respect for marriage act. Retrieved from http://www.hrc.org/laws-and-legislation/federal-legislation/respect-for-marriage-act?gclid=COXbopG2qLCFenm7AodRAMAzw

- Killian, M. L. (2010). The political is personal: Relationship cognition policies in the United States and their impact on services for LGBT people. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 22(1-2), 9-21.

- Liptak, A. (2015). Supreme court ruling makes same-sex marriage a right nationwide. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/27/us/supreme-court-same-sex-marriage.html

- Mathy, R. M., Kerr, S. K., & Lehmann, B.A. (2004). Mental health implications of same sex marriage: Influences of sexual orientation and relationship status in Canada and the United States. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 15(2-3), 117-141.

- Mathy, R. M., & Lehmann, B. A. (2004). Public health consequences of the Defense of Marriage Act for lesbian and bisexual women: Suicidality, behavioral difficulties, and psychiatric treatment. Feminism and Psychology, 14(1), 187-194.

- Morse, J. M. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 220-235). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Moustakas, C. 1994. Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Pelts, M. D. (2014). A look back at the Defense of Marriage Act: Why same-sex marriage is still relevant for social work. Journal of Women and Social Work, 29(2), 237-247.

- Pizer, J. C. (2016). Lambda Legal condemns passage of anti-LGBT Mississippi bill HB 1523. Retrieved from https://www.lambdalegal.org/blog/20160405_ms-hb-1523

- Reilly, R., & Siddiqui, S. (June 26, 2013). Supreme Court DOMA decision rules federal same-sex marriage ban unconstitutional. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/06/26/supreme-court-domadecision_n_3454811.html

- Rimmerman, C. (2008). The lesbian and gay movements: Assimilation or liberation? Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Sterngass, J. (2012). Same-sex marriage. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish Corporation.