Irish Families and Globalization: Conversations about Belonging and Identity across Space and Time

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Chapter 1: The Irish Geosystem and Family Well-Being

Remarkable as the bioecological theory of Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979, 1994) is in accounting for the influence of contextual factors on developmental outcomes, a noteworthy omission is acknowledgement of the relationship of the developing person and the natural physical environment. Yet, clearly each place/locale/physical environment with its unique assembly of living and non-living elements “pulls for” unique developmental experiences and outcomes. In today’s rapidly changing, globalized world, characterized by the exchange of information, goods, and people across boundaries of space and time, is a swirling backdrop of social and environmental phenomena—rising CO2 levels, loss of polar and glacial ice, and storm intensification; the interiorization of human activity in advanced technological societies and crisis levels of obesity, diabetes, and heart failure; dwindling worldwide safe water sources along with limited natural resources challenging survival in many developing countries—that make it hard to deny the natural environment as an influence on the daily lives of developing individuals, families, and communities and reckless to ignore the impact of people on the natural environment.

Posited as an additional system in Bronfenbrenner’s nested systems conceptualization, this author places the geosystem as the external and all-encompassing system containing Bronfenbrenner’s chronosystem, macrosystem, exosystem, mesosystem, microsystem, and individual (see Figure 2).

Definition 1

The geosystem is the natural physical environment that contains individuals, families, and communities. It is comprised of the living and non-living elements of the natural world and includes land, water, and air (see Christopherson, 2011). The geosystem offers a physical place in which each individual—child, youth, and adult—develops. The relationship between each system and geosystem is reciprocal, and risk and opportunity flow bi-directionally.

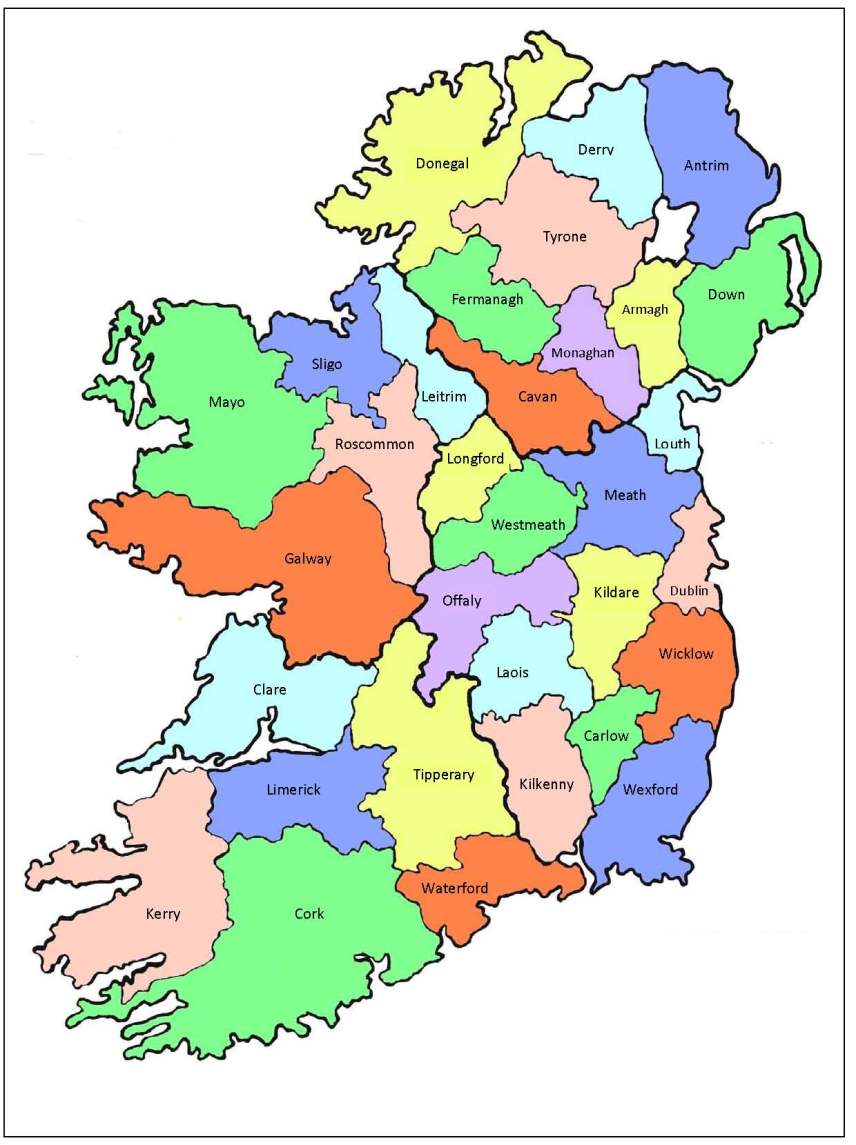

For the purposes of this paper, the geosystem of focus and explication is that of the two countries occupying one island in the northern Atlantic Ocean—Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. And the developing person is assumed to be any singular human being at any life stage—child, adolescent, or adult—in any role—family member, citizen, worker, public official, and so on. Representative illustrations are drawn from reading, observation, conversation, and reference to contributions of authors in this volume as well as presenters at the Groves 2008 Conference in Ireland.

Proposition 1

The geosystem influences the individual through the direct and indirect affordance of risk and opportunity for development incrementally or abruptly, and, conversely, the developing person impacts the geosystem through independent or collective action, inaction, or reaction, at all levels—individual, microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem.

To direct my argument and guide our thinking I will discuss developing person-geosystem relations beginning with the chronosystem. Bronfenbrenner (1994) introduced the chronosystem as a system encompassing:

...change or consistency over time not only in characteristics of the person but also of the environment in which the person lives (e.g., changes over the life course in family structure, socioeconomic status, employment, place of residence, or the degree of hecticness and ability in everyday life. (p. 40)

Postulate G1a

At the level of the chronosystem, physical events or processes of the geosystem that shape the earth’s surface occurring at a specific point in time or accrueing over time can produce and comprise a chronosystem event with the potential of impacting a developing person’s life, positively or negatively, placing the individual at risk or advantage for development.

In Irish history the most compelling physical event, captured in historical record as the Great Potato Famine of the late 1840’s, was caused by an airborne fungus that abruptly and profoundly diminished opportunities for life with millions dead and fled (estimates are 1,000,000 dead from starvation and 2,000,000 emigrated) (see Donnelly, 2002). And just as a geosystem event, such as that phytophthora infestans blight, may define a chronosystem event that depletes opportunity for individuals, another may provide plenty, as in the Dingle Peninsula fishing boon concomitant with the Great Famine—where natural resources were found and tapped through fishing (see Dingle Peninsula, 2014; Graham, 1996). The Dingle Peninsula is defined by a sandstone rock ridgeline, jutting out from the southwest coast of County Kerry into the Atlantic Coast and rimming Dingle Bay. For decades, generous catches of demersal fish, such as sole, provided sustenance for the middle class and gentry and oily fish, such as herring, for the poor of this region. Even if potatoes were rotten and wheat was being shipped out of Ireland to England, the fishing boon, courtesy of an enriched ocean environment, enabled many to eat and survive, if not thrive.

Postulate G1b

Chronosystem events orchestrated by the independent or collective actions of individuals impact the geosystem.

How can we demonstrate that chronosystem events orchestrated by the actions or inactions of individuals, wittingly or unwittingly, impact the geosystem both positively or negatively? Consideration of a contemporary chronosystem event, that is Ireland’s membership in the European Union, and further attention to the historic event of the Great Famine demonstrate that it is possible for the developing person to play a reciprocal and contributing role within the context of a chronosystem event to help produce a life-enhancing benefit or life-detracting catastrophe in the geosystem. Membership in the European Union can be construed as a chronosystem event in the lives of most in Ireland (see Wyndham, 2006, and Foster, 2008, for a discussion of the social and economic events attendant with membership that were ushered in at a “rate of breakneck change,” p. 186).

A single initiative out of many possible to consider is the European Union’s LIFE-Nature Project. One of 55 proects funded in Ireland over a six-year period from 2000 to 2006 was focused on the re-introduction of the Golden eagle to the Republic of Ireland with a two-pronged aim: to reintroduce the species to an appropriate habitat, in this case Glenveagh National Park with its rocky precipices, woodlands, freshwater lakes, and blanket bog in Donegal (County Donegal), and to raise awareness of the species and engender pride in contributing to the restoration of part of Ireland’s natural heritage (see Glenveagh National Park, n.d.; Golden Eagle Trust, n.d.). Coordinated by the Irish Raptor Study Group, an NGO foundation that conducted the study, with school children and members of the local and national community engaged in awareness and education events, project successes (43 eagles established in the park with a first birth occurring in 2007) and growing knowledge and enthusiasm of all participating demonstrate the positive impact of individual actions occurring within a chronosystem event, such as European Union membership, can have on the geosystem.

Turning back to the Great Potato Famine, it can be shown how the chronosystem can negatively impact the geosystem. Quite simply, by the middle of the 1800’s the population of Ireland, particularly that of the west, had outstretched the provisions of its limestone burren and scant soil. With more mouths to feed cheaply, families became increasingly reliant on the potato, to the exclusion of other foodstuffs. With only one crop in fields, when the blight struck over a series of very wet growing seasons, the soil yielded nothing but rotting tubers (Donnelly, 2002).

At the level of the macrosystem, the geosystem provides the setting for the establishment of patterns of social organization and influences the complexity and fluidity of social organization. Bronfenbrenner (1994) defined macrosystem as

the overarching pattern of micro-, meso-, and exosystems characteristic of a given culture or subculture, with particular reference to the belief systems, bodies of knowledge, material resources, customs, lifestyles, opportunity structures, hazards, and life course options that are embedded in each of these broader systems. (p. 40)

Postulate G2a

The geosystem with its presence or absence of physical resources (living and non-living) influences individual development at the level of the macrosystem to the extent that it allows for the creation and sustenance, or the devolution and destruction, of institutions of education, faith, commerce, and government.

Historically, the geosystem of Belfast (Counties Atrim and Down) in Northern Ireland has conveyed particular benefit allowing the city to become a thriving international center of shipbuilding and commerce (Royle, 2003). The natural environment includes a temperate oceanic climate, warmed by the North Atlantic Current of the Gulf Stream, with a coastline that never freezes in the winter and a flat glacial trough drained by the River Lagan as it and its tributaries flow into Belfast Lough (Lake) and from there to the Irish Sea. Among other industries such as linen, engineering, and chemicals, shipbuilding emerged, first with wooden ships in the 18th century and later during the 19th and into the 20th centuries with ships of iron and steel. Here, the firm of Harland and Wolfe, the world’s largest shipbuilder in the early 20th century, constructed high-quality ships for the Royal Navy and shipping companies around the world, as well as ocean-going liners including the Titanic, and employed thousands at its zenith (see Gillespie & Lynch, 2003; OBrolchain, 2003). In the example of Belfast the positive contribution of geosystem characteristics to the generation of macrosystem functioning, particularly in the promotion of institutions of commerce and trade, can be seen.

The proximate geographic location of Ireland to the British Isles, a geosystem landform phenomenon, provides a means of understanding geosystemic impact on a macrosystem with life-altering negative impacts. Not only is Ireland close to the British Isles, it is comprised of a central plain rimmed with low coastal mountains (see Green, 2014) with easy access from the east and the Irish Sea allowed by one 90-kilometer stretch, from the Wicklow Mountains (County Dublin) north to the Carlingford Peninsula (County Louth). As early as the 1500’s the English Crown established plantations in Ireland, supplanting Irish inhabitants with Protestant settlers from Scotland, England, and Wales (see Jefferies, 2003). For example, the Plantation of Munster, ordered by Queen Elizabeth I, confiscated almost 300,000 acres of Irish land in the southernmost and largest province of Munster (comprised of Counties Clare, Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary, and Waterford and including towns such as Waterford and Cork) (see Brady, 2003b), and by 1641 there were 22,000 settlers in the area, transforming the economy and society (see Nunan, 2012). Despite explicit goals of establishing obedience to the English monarchy by introducing English-style civility and establishing Protestantism that were incompletely realized, macrosystemic by-products of these settlement projects included sustained involvement of England administration in Irish political affairs, changing agricultural practices such as fencing and fertilization, extraction of natural resources such as timber, iron, and fisheries, and loss of life from rebellions and war.

Postulate G2b

Via the macrosystem to the extent that the individual espouses and acts on values that contribute to environmental sustenance or degradation, in the enhancement or depletion of resources or the death of species, through its institutions of social organization, the geosystem is diminished. And, when the individual espouses and acts on values, by acts such as voting, being educated, living simply, allowing for the continuation of life of indigenous plants and animals and the use of renewable resources via institutions of education, faith, government, and so on, the geosystem is sustained.

Perhaps a macrosystem-to-geosystem benefit is overlooked in the case of the unsettled Irish Traveller or tinker (tinsmith) culture; Travellers are often referred to erroneously as gypsies. According to the 2011 Census (Central Statistics Office), there were 29,573 Travellers in the Republic of Ireland (0.6% of the population). In total 40,000 Travellers reside in the Republic and Northern Ireland, according to the All Ireland Traveller Health Study Team (2010). Children under 18 comprise about half the Traveller population, and most Travellers live in urban rather than rural areas.

The unsettled Traveller family persists in not buying and acquiring property, despite government efforts to promote settlement, occupies field or public fringe area instead, and maintains a simple way of life, using little of the earth’s resources, at one time not much more than sticks and water. During the 50s and 60s, Travellers made their livings making buckets, sweeping chimneys, swapping horses, collecting and selling scrap, and asking for hand outs (see MacWeeney, 2007). Today, countervailing outcomes of the Traveller life continue to include high birth rates with high rates of death by age 2 and truncated longevity. The All Ireland Travellers Health Study revealed a life expectancy of 61.7 years for males, 70.1 for females. Condon (2014, March 9) notes a “strong sense of community and high levels of community/family support” (p. 3) within the Traveller culture. Drawing on one’s own resources and using few provided by others or the natural environment can serve as one example of a positive macrosystemic impact of cultural values on the geosystem.

Failure to act can have as negative an effect on the environment as a specific act. Ireland, like other advanced technological societies, has developed a reliance on oil (in addition to electricity generated by the burning of peat). Not only is oil (and peat) a finite resource, an environmental toll is paid in its discovery, acquisition, and use. Ireland imports most of the fuel it needs for electricity generation. Ireland’s indigenous energy supply reveals 40% renewables, 1% energy from waste, 38% from peat, 21% from native gas. Bord na Mona, an Irish utility company, harvests peat on 8% of the area formerly classified as raised bogs, justifying its extraction and conversion to electicity as one means of increasing Ireland’s energy security (Bord na Mona, n.d.).

A noteworthy trend is the growth of wind-generated power in Ireland, perhaps its most reasonable alternative to fossil fuel use. Today 210 wind farms in Ireland produce 18% of Ireland’s electricity (Irish Wind Energy Association, 2014, March 10; see also Bord na Mona). Yet, a widely distributed and coordinated system of wind turbines on and off shore connected to the existing power grid requires more political will power, derived from individuals insisting on alternatives and an elected government compelled at the insistence of the electorate to make the investments necessary to bring such a system to fruition. In the absence of action, steered by a strong macrosystemic ethic of environmental protection, environmental degradation from increased levels of CO2 production and global warming will continue to be the geosystemic outcome.

Several examples illustrate the reciprocal relationship of geosystem and exosystem. Bronfenbrenner (1994) defined the exosystem as:

...the linkages and processes taking place between two or more settings, at least one of which does not contain the developing person, but in which events occur that indirectly influence processes within the immediate setting in which the developing person lives (e.g., for a child, the relation between the home and the parents’ workplace; for a parent, the relation between the school and the neighborhood peer group (p. 40).

Postulate G3a

When the geosystem, by virtue of its wealth of and access to resources allows families ease of access to work and commerce and community activity, making it easier for parents to parent or teachers to teach, for example, opportunities for development of the individual are more likely to accrue. Alternatively, when the geosystem, by virtue of a dearth of resources or distribution of sources of commerce and community activity that limits accessibility of families to such resources, conditions make it more difficult for parents to parent and children/individuals are placed at risk for development.

Both positive and negative impacts of the geosystem on the exosystem can be seen in recent actions of Diageo, the parent company of Guinness Beer in the Republic of Ireland. First, in 2008, Diageo announced plans to reduce its brewery employees in Dublin (County Dublin), the capital of the Republic and Irish Sea-facing port city, by half and close down two smaller breweries outside of Dublin (Pogatchnik, 2008, May 10). With water from the Wicklow Mountains an hour north of Dublin, beer has been made on the banks of the River Liffey in Dublin and shipped down the river to the port to be loaded on tanker ships and transported to London and beyond, since the 1700s. The famed Guinness Brewery at St. James Gate in Dublin was to see its workforce reduced from 230 to 65. A new more efficient brewery was planned for the suburbs of Dublin with a possibility of 100 jobs there. Given the different modes of transport available today, location on the Liffey was viewed as only symbolic and no longer instrumentally essential for the corporation. Corporate officials cited increased competition from Eastern Europe, Russia, and China and pubgoers’ changing tastes, as the forces compelling change. But, how quickly things can change. Pogatchnik (2012, January 12) updated his earlier report with news that the economic downturn of the global recession had compelled Diageo to scuttle plans of conversion of the Dublin brewery site to real estate. Now, Diageo is building a new and enlarged plant at the St. James site in Dublin, while still closing the two other Irish breweries, the latter at the cost of 100 jobs.

Accordingly, for Guiness employees who are also parents it can be inferred that doing the job of parenting is easier now that jobs have been retained in Dublin instead of being moved to the outskirts of the area. Keeping jobs in Dublin confers benefits of proximity of home and workplace that allow parents to better sustain their attentions to and enagements with their developing children. It is noteworthy that for centuries Guinness employed many who lived in the surrounding Dublin neighborhoods, including the residents of Fatima Mansions, a community visited during the 2008 Groves Conference. Over time technological advances have shrunk the workforce from thousands to hundreds, and now few Fatima families find their livelihoods at Guinness. Clearly, children will continue to be effected by Diageo’s decisions, as unemployed parents, such as those now impacted by the small brewery closings in Dundalk and Kilkenny struggle to find other employment or acquire new positions farther away from home at the enlarged plant in Dublin.

Another phenonmenon shows how opportunity or risk can accrue to the developing person from the geosystem via the exosystem. In Ireland rates of breastfeeding are rising, yet, whereas over 90% of women breastfeed in Scandinavia, only 56% initiate breastfeeding in Ireland (The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) 2012, October 1). Furthermore, there are regional variations. For example, in Dublin 6 out of 10 babies are breastfed as opposed to 4 out of 10 in Donegal. This discrepancy suggests that exosystem forces, such as promotion of breastfeeding in birthing classes and encouragements in hospitals, may be in part determined by geographic location, making it more likely for the individual baby being born in Dublin, the Republic’s capital and largest city situated in a landscape of gentle hills and lowlands on the eastern coast (see Brady, 2003a), as compared to Donegal (County Donegal), a small isolated Atlantic (Donegal Bay) coastal town, separated from the rest of the Republic by its border with Northern Ireland, with sparse natural resources limiting economic development and geographical impediments to communication (e.g., Bluestack Mountains), to be offered a form of feeding known to promote parent bonding, establish infant attachment, and build a strong immune system (see Proudfoot, 2003, for descriptions of geographic locations). Other factors, of course, are associated with Irish mothers’ continuation of breastfeeding and must be acknowledged in this discussion, including length of maternity leave for working mothers, and mothers’ age, country of birth (Eastern European born mothers were more likely to breastfeed), and absence of depressive symptoms (ESRI, 2012), illustrating the complexity of reciprocal relations simultaneously occurring between systems impacting the developing person.

Postulate G3b

Conversely, the exosystem, as an influential system not containing the individual, can impact the geosystem positively or negatively.

In what way might the exosystem impact the geosystem? For example, the Department of the Environment, Heritage, and Local Government provides funding in the Republic for environmental awareness projects, along with public information designed to encourage children and adolescents to be environmentally responsible. To the extent that such programming makes it easier for parents and teachers to teach their children about the environment and children more likely to engage in environmental care activities, a positive effect of the exosystem on the geosystem may be realized. The Regeneration Board, for example, at Fatima Mansions, has supported families through the visioning, planning, and reconstruction process of their revitalized neighborhoods. Supported by the Board, parents proposed and implemented community gardening and recycling projects as simple means for involving their children and the neighborhood in caring for the environment (see Whyte, 2005, and this volume).

A point of contrast and illustration of a potentially negative effect of an exosytem on the physical environment can be seen in the example of the recent appointment of an agri-food executive, a senior level executive in finance in the meat processing industry, to the Livestock and Meat Commission (LMC) (Northern Ireland Executive, 28 January 2014). The LMC is sponsored by the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development to assist the development of livestock and livestock product section of the agri-food industry. In light of previous responses to the appointments of industry representatives rather than farmers to the LMV, this latest appointment adds to perception that the board tilts its attentions more to the meat packing companies than to the providers of red meat, the farmers, whose numbers and incomes are declining (see Rev. Dr. Ian Paisley’s comments to the Northern Ireland Assembly, 2001). Remarkably, in Northern Ireland, (see Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute, 2011) 76% of the total land area is devoted to agriculture (as compared to an EU average of 40%; see Rural Support, 2008) with most of that under grass, as opposed to crops (only 5% of farmland), due to heavy, poorly draining soils and high seasonal rainfall. Most farms are classified as very small, providing full-time employment for one person, and are family-owned and occupied; and the size of farms is increasing as the number of farms decreases

(Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, 2013; McKenna, 2008). Negative geosystem effects of cattle and dairy farming are well-known—land degradation, water and biodiversity loss, and climate change are more likely to occur when industry interests predominate over those of individual small farmers and farm families and decisions impacting farmers and families are made in an arena that limits representation of small farm interests.

The mesosystem, according to Bronfenbrenner (1994), is comprised of “linkages and processes taking place between two or more settings containing the developing person (e.g., the relations between home and school, school and workplace, etc). In other words, a mesosystem is a system of microsystems” (p. 40). In strongly linked systems, according to Bronfenbrenner, in addition to the child, multiple significant others accompany the child from one setting to another, and ideally bonds of trust are established between participants in these respective settings. In weakly linked systems, it is the individual alone who goes back and forth between settings.

Postulate G4a

If the geosystem allows for settlement patterns in communities with opportunities for commerce, government, education, and health care clustered in close proximity, the geosystem can be found affording opportunity for development at the mesosystem level. Alternately, when geographical setting compels the establishment of microsystems that are widely dispersed, it is more likely that the microsystems will be weakly linked with the developing individual often the sole link between settings and therefore at risk.

A scenario in which the geosystem allowed for settlement patterns clustered in close proximity can be found in Arensberg’s (1968) 1930’s description of rural family life in western Ireland. After the government decreed that family farms could no longer be subdivided into ever more tiny plots, yet family sizes remained large due to the urgings of the Catholic church, the farm was taken over and passed down to only one child, usually the oldest son, who took a wife and began a new nuclear family. The old mother and father moved to the west room, ceding the operation of the farm to their son. Remaining siblings, if they were male became priests or playboys (bachelors), girls shopkeepers in nearby towns. And, thus, town-farm relations were cemented, tying together concerns of family life and commerce.

When microsystems are widely dispersed within the geosystem setting, it is more likely that the developing individual will be the sole link between settings (the mesosystem) and at risk for further development. Today in Northern Ireland, Belfast in particular, it is increasingly difficult for new young families to afford to buy a home in the urban neighborhood in which their own families may have lived for generations. It is becoming increasingly necessary for older parents, who own their own home, to take out a second mortgage in order to help their children buy one of their own. And affordable new homes are being built further and further away from the city on former farmlands (Belfast banker, personal communication, 2007). So with customary residential patterns changing due to lack of access to nearby land for housing, traditional family roles and activities are altered and opportunities for ongoing family relations are attenuated, family bonds weakened, and individuals, such as aging parents who remain in the city and grandchildren far-removed from their grandparents, are short-changed, while the young parent who still travels back and forth to work in the city and drops in on the family as time allows, is the single extended family link.

Postulate G4b

Mesosytemic relationships generate positive or negative outcomes in the geosytem, to the extent that these relationships allow for the goings back and forth and coordinated activities of multiple microsystem members as opposed to the solitary activity and goings back and forth of a single developing person between microsystems.

Pursuant to the Diaspora associated with the Great Depression and economic hard times, more folk of Irish heritage live without rather than within Ireland. With the upturn in the economy associated with the affiliation of the Republic with the EU and the abatement of the Troubles, many people returned to the island of their own or their parents’ birth. More recently, in tandem with the global recession, “Ireland has gone from having the highest net immigration levels in Europe to the highest net emigration levels in just six years” (Kenny, 2013, November 21, p. 1). In 2012, 35,000 more people left Ireland than arrived with a net outward migration (emigration) rate of -7.6 people per one thousand inhabitants. By contrast, in 2006 at the height of the economic boom, 22.2 per 1000 inhabitants immigrated into Ireland. Still, with the highest birth rate and lowest death rate in Europe, Ireland has the highest natural population growth.

With the return of those of Irish heritage to Ireland during the years of Celtic Tiger economic opportuntity, there was potential for a positive mesosytemic contribution to the physical environment as returning individuals and families re-established relationships with other members of the extended family system and community in Ireland and in so doing strengthened mesosytemic linkages. With a perspective on the geosystem and its fragility, perhaps shaped by experiences with the excesses of economic abundance and environmental degradation or geosytem care successes in the United States or England, such individuals and families may have been better poised to help avert or promote these outcomes in Ireland. In this presumed new and more strongly linked mesosystem, individuals and families had the potential to make a unique and enduring positive contribution to geosystemic health. In the more recent reality of increased outward migration and attendant attenuated mesosytemic relations, fewer are left to embrace the ethic and shoulder the tasks of geosystem care at home in Ireland.

The lone parent family, exemplifying Bronfenbrenner’s two legged stool analogy, is also emblematic of a weakly linked mesosystem, making a positive contribution to the geosystem less likely. In the absence of a supportive and customary third leg, individual family members are less likely to be accompanied from one setting to another, leaving that developing individual, be it mother or child, at risk (see Millar, Coen, Bradley, & Rau, 2012). At Fatima Mansions, a Dublin Corporation neighborhood regeneration project, a disproportionate number of such families suggests a potentially deleterious and indirect effect on the geosystem. Often elevated drug, alcohol, and tobacco use, under- or unemployment, lower levels of school attendance, school achievement, and civic participation are the developmental outcomes associated with lone parenthood, and such families’ use of resources from the geosystem may far outstrip their contribution to the physical environment and curtail the individual’s abilities to coordinate earth-friendly action between settings (see Whyte in this volume for conversation about community development strategies employed in the regeneration project to address these individual and family issues).

The geosystem also impacts the microsystem,

a pattern of activities, social roles, and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing person in a given face-to-face setting with particular physical, social, and symbolic features that invite, permit, or inhibit engagement in sustained, progressively more complex interaction with, and activity in, the immediate environment. Examples include such settings as family, school, peer group, and workplace. (Bronfenbrenner, 1994, p. 39)

Postulate G5a

To the extent that the geosystem is hospitable to the family, for example, in the affordance of clean air, abundant food, fresh water, a mild climate and so on, the more likely the microsystem will flourish as a setting for promoting the development of individuals within that system, allowing the developing individual to establish enduring reciprocal relationships that are the basis of doing more and in which the power in the relationship shifts gradually in favor of the developing individual. And to the extent that access to any of these positive natural resources is limited, the microsystem is diminished, and, accordingly, the the child or developing individual within that system is assumed to be at risk.

One example of positive geosystem effect on the microsystem can be seen in Waterford (County Waterford), the oldest and sunniest city in the Republic, situated on the southeast coast on an estuary of the river Suir with access to the Celtic Sea and maintaining an active commercial tradition over hundreds of years (Hourihan, 2003). In 1783, a factory was established for the manufacture of fine flint glass with requirements for quantities of ash trees for alkali and English sand (see Westropp, 1911/1912). Today, the child of a Waterford Crystal Factory employee continues to be afforded the opportunity for apprenticeship and employment, following in the footsteps of relatives, should she choose. On the heels of the 2008 financial crisis, Waterford Crystal was acquired by a leading luxury good group and a new manufacturing facility was built in the heart of the city in 2010, assuring jobs for craftsmen and their families for years to come (House of Waterford Crystal, 2014). In contrast, to the extent that access to any of these positive natural resources is limited, the child or developing individual is assumed to be at risk. The geography of the Burren, a denuded limestone pavement landscape occupying 250 square kilometers in northwest county Clare, simply cannot sustain a major population center and the attendant development of social institutions of commerce, education, and government (see http://www.burrennationalpark.ie/).

Postulate G5b

The microsystem through the collective actions and inactions of its members contributes to the health or destruction of the geosystem.

In the example of a single Irish family, a positive example can be found. Willie Corduff, his wife, and children live in a small northwest coast village, Rossport (County Mayo), on the Northern Sea. Off shore, Shell Oil has discovered oil. Shell Oil planned to build pipes above ground to transport oil from the continental shelf to its refinery inland, going through the village of Rossport. Despite Shell Oil’s insistence that no harm would befall the residents of Rossport or the environment, Willie Corduff and family have succeeded in drawing first village and now national and international attention to this situation (see Shell to Sea at www.shelltosea.org). At last report, Shell Oil is exploring alternate means of getting oil from ocean to refinery with less of a physical environmental impact, and one family’s actions are positively influencing the geosystem (see www.Shell to Sea.org). Currently the Corduff family is helping to uncover corporate malfeasance including “sweeteners” or pay-offs to people of the region including alcohol to the police and other gifts such as tennis courts, television sets, and school fees (Vulliamy, 2013, August 10), as a means of applying public pressure to avert a geosystem disaster.

What serves to illustrate negative microsytem impact on the geosystem? A venerated microsystem in Irish history is the Catholic Church on which individuals relied for instrumental and spiritual support. Yet, this same church should be considered complicit in the social debacle and environmental imbalance that precipitated the Great Famine with its continued condemnation of contraception. With fields and sea yielding only so many natural resources, particularly foodstuffs, and birth rates climbing at a rate disproportionate to these resources, in response to unyielding dictates of the church about birth control in particular, environmental degradation, disaster, death, and diaspora ensued. How is the individual, defined here as the developing person, impacted by the geosystem?

Postulate G6a

The geosystem influences the individual through the direct affordance of risk and opportunity for development. At the level of the individual, physical events or processes that shape the earth’s surface may occur abruptly, as with a flood, or slowly and incrementally, as in steady deforestation.

If, for example, a child is born today in Tir an Fhia on the west coast of County Galway, established as a fishing village generations ago (and visited by Groves in 2008), he will be unable unlike his forebears to make a living as a fisherman when he grows up. As with fisheries worldwide, catches are diminishing and making a livelihood from commercial fishing is less possible. Yet, as the surrounding region of Connemara becomes a center for preservation of the Gaelic cultural heritage and a tourist destination with its raw natural beauty, the growing child may have other opportunities for school and work and engagement in the world—such as in ecotourism or sport fishing (see O’Coistealbha, this volume).

Postulate G6b

Alternatively, actions or inactions of individuals in the specific physical environment contribute directly to geosystem events.

On the one hand, the sheep farmer in Connemara who cuts peat for fuel from blanket bogs, and allows his sheep to graze there as well, irrevocably alters the physical terrain, damaging habitat for other flora and fauna, and contributes to global warming. The Irish Peatlands Conservation Council (n.d.) reports that peat being used up by industrial extraction for electicity generation, private turf cutting for personal fuel use, and moss peat extraction for use in horticulture comprises a loss of 47% of the original Irish peatlands. On the other hand, the child who planted a tree this March as part of the National Tree Week 2014 celebration joins a nationwide effort to increase the amount of land planted in trees in Ireland from its current 11% to a goal of 17% in 2035 (European average is 40% coverage) plays a role in “mitigating against climate change by soaking up carbon emissions” (Tree Council of Ireland, 2013, p. 2). Ireland’s loss of extensive forests of oak, elm, Scots pine, and ash by 1800 are attributed to timber clearing for ship building, for the industrial production of iron, glass, and barrels, and well as increased demands for food and shelter for a burgeoning population (Forest Service, 2008).

Conclusion

To the extent that opportunity for development outweighs risk for individuals, families, and communities and the extent that the land, water, and air continue to support the living things in a particular physical place, the geosystem is assumed to be in balance. To the extent that risk for development outweighs opportunity and the extent to which the land, water, and air are unable to support life, the geosystem is assumed to be out of balance. In Ireland, both the Republic and Northern Ireland, the geosystem appears to afford individuals, families, and communities more opportunity than risk for development. On the other hands, as in other countries on earth, individuals, families, and communities are placing stressors on their natural physical environment that may be contributing to a geosystem that is increasingly out of balance. In view of the demonstrable contributions of the physical environment to human and family functioning and the impact of developing persons and their families on the natural environment, family scientists are urged to include the geosystem in their studies of and conversations about child and family well-being.

References

- Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute. (2011). Dairyman-Action 1 regional report on sustainability Northern Ireland: An assessment of regional sustainability of dairy farming in Northern Ireland. Retrieved from [formerly http://www.interregdairyman.eu/upload_mm2/6/4/bba8dca7-41ae245e47a25_NI-Regional_Report_-_WP1A1.pdf]

- All Ireland Traveller Health Study Team. (2010). All Ireland Traveller health study. Dublin, Ireland: University College Dublin.

- Arensberg, C. M. (1968). The Irish countryman: An anthropological study. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

- Bord na Mona (n.d). Peat. Retrieved from http://www.bordnamona.ie/our-company/our/businesses/feedstock/peat/

- Brady, J. (2003). Dublin. In B. Lalor (Ed.), The encyclopedia of Ireland (pp. 318-320). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Brady, J. (2003). Munster. In B. Lalor (Ed.), The encyclopedia of Ireland (p. 749). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In M. Gauvain & M. Cole (Eds.), Readings on the development of children (2nd ed., pp. 37-43). New York, NY: W.H. Freeman. (Reprinted from International encyclopedia of education, 2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 1643-1647, by T. N. Postlethwaite & T. Husen, Eds., 1994, Oxford, England: Elsevier.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Central Statistics Office. (2011). Census 2011 profile 7 religion, ethnicity and Irish Travellers-Ethnic and cultural background in Ireland. Retrieved from [formerly http://www.cso.ie/en/census2011profile7religionethnicityandirishtravellers-ethnicityand culturalbackgroundinireland/]

- Condon, D. (2010, March 9). Life expectancy of Travellers remains low. Retrieved from http://www.irishhealth.com/article.html?id=17830

- Christopherson, R. W. (2011). Geosystems: An introduction to physical geography (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

- Department of Agriculture and Rural Development. (2013). The agricultural census of Northern Ireland. Belfast: Department of Agriculture and Rural Development of Northern Ireland. Retrieved from http://www.dardni.gov.uk/agricultural_census_in_ni_2013_1.pdf

- Dingle peninsula. (2014, June 8). Retrieved from http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dingle_Peninsula

- Donnelly, J. (2002). The great Irish potato famine. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing.

- Economic and Social Research Institute. (2010, October 1). Breastfeeding in Ireland 2012: Consequences and policy responses [press release]. Retrieved from https://www.esri.ie/news_events?latest_press_releases?breastfeeding_in_ireland_/index.xml

- Forest Service. (2008). Irish forests – A brief history. Wexford, IE: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food. Retrieved from http://www.agriculture.gov.ie/media/migration/forestry/forestservicegeneralinformation/abouttheforestservice/IrishForestryAbriefhistory200810.pdf

- Foster, R. F. (2008). Luck and the Irish: A brief history of change from 1970. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Gillespie, G., & Lynch, J. P. (2003). Belfast shipbuilding. In B. Lalor (Ed.), The encyclopedia of Ireland (p. 86). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Glenveagh National Park. (n.d.). Dublin, IE: National parks and wildlife service. Retrieved from http://www.glenveaghnationalpark.ie/

- Golden Eagle. (n.d.). The reintroduction of Golden Eagle into the Republic of Ireland. Retrieved from http://www.ec.europa.eu/environment/life/project/Projects/index.cfm?fnseaction=search.dsp&n_proj_id=1736&doctype=pdf

- Graham, D. (1996). Fishing on the Dingle peninsula. Kerry, IE: Dingle Peninsula Tourism. Retrieved from http://www.dinglepeninsula.ie/culture1.html

- Green, M. (2014). An outline geography of Ireland. Blackrock, IE: The Information about Ireland Site. Retrieved from http://www.ireland-information.com/reference/geog.html

- Hourihan, K. (2003). Waterford. In B. Lalor (Ed.), The encyclopedia of Ireland (pp. 1125-1126). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- House of Waterford Crystal. (2014). Waterford crystal-Its history and heritage. Retrieved from http://www.waterfordvisitorcentre.com/Press/Fact_Sheets/History_of_Waterford_Crystal

- Irish Peatland Conservation Council. (n.d.). Over-exploitation of peatlands for peat. Kildare, IE: IPCC. Retrieved from [formerly http://www.ipcc.ie/a-z-peatlands/peatland-action-plan/over-exploitation-of-peatlands-for-peat/]

- Irish Wind Energy Association. (2014, March 10). Wind statistics. Retrieved from http://www.iwea.com/_windenergy_onshore

- Jefferies, H.A. (2003). Plantation of Munster. In B. Lalor (Ed.), The encyclopedia of Ireland (p. 877). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Kenny, C. (2013, November 21). Ireland has highest net emigration level in Europe. Irish Times. Retrieved from [formerly http://www.irishtimes.com/news.com/news/social-affairs/irelad-has-highest-net-emigration-level-in-europe-1.1601685]

- MacWeeney, A. (2007). Irish travellers: Tinkers no more. Heniker, NH: New England College Press.

- McKenna, F. (2008). Agriculture in Northern Ireland. Retrieved from [formerly http://www.thinkgeography.org.uk/A2%20Human/Unit%20D/....htm]

- Millar, M., Coen, L., Bradley, C., & Rau, H. (2012). Doing the job as a parent: Parenting alone, work, and family policy in Ireland. Journal of Family Issues, 33, 29-51.

- Northern Ireland Executive (2014, January 28). New appointment to Livestock and Meat Commission. Retrieved from http://www.northernireland.gov.uk/news-dard-280114-new-appointment-to

- Nunan, J. P. (2012). The planting of Munster 1580-1640. Dublin, IE: Public Outreach Series. Retrieved from [formerly http://www.jpnunan.com/sitebuilderscontent/sitebuildersfile/josephnunanmunsterplantation.pdf]

- OBrolchain, F. (2003). Shipbuilding. In B. Lalor (Ed.), The encyclopedia of Ireland (p. 988). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Paisley, I. M. (2001, October 9). Livestock and Meat Commission, Northern Ireland Assembly debates. Retrieved from [formerly http://www.theyworkforyou.com/ni/?id=2001010-09.4.015=speaker%3Aa3772]

- Pogatchnik, S. (2012, January 12). Guiness to build massive new Dublin brewery. Retrieved from http://www.nbcnews.com/id/45973979/ns/business-world_business/t/guiness-build-massive-new-dublin-brewery/ - .UzBeov3nwds

- Pogatchnik, S. (2008, May 10). Diageo to overhaul Guinness. Miami Herald, p. 2C.

- Proudfoot, L. (2003). Donegal, County. In B. Lalor (Ed.), The encyclopedia of Ireland (p. 305). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Royle, S. A. (2003). Belfast. In B. Lalor (Ed.), The encyclopedia of Ireland (p. 82). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Rural Support (2008). Agricultural landuse. Retrieved from [formerly http://www.mygroupni.com/RuralSupport/directory/?module=Item%20Detail&itemid=6713edac-2d94-43e4-98de-f2280b8cac3%directoryid]

- Tree Council of Ireland. (2013). The sound of trees. Retrieved from [formerly http://www.treecouncil.ei/initiatives/initiatives.html]

- Vulliamy, E. (2013, August 10). Strange tale of Shell’s pipeline battle, the Gardai and L30,000 of booze. The Observer. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/aug/10/shell-pipeline-protests-county-mayo/print

- Westropp, M. S. D. (1911/1912). Glassmaking in Ireland. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 29, 34-58.

- Whyte, J. (2005). Great expectations: A landmark and unique social regeneration plan for Fatima Mansions. Dublin, Ireland: Fatima Regeneration Board Ltd.

- Wyndham, A. H. (Ed.) (2006). Re-imagining Ireland: How a storied island istransforming its politics, economy, religious life, and culture for the twenty-first century. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.