Imagination and the Distinction between Image and Intuition in Kant

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

The role of intuition in Kant’s account of experience receives perennial philosophical attention. In this essay, I present the textual case that Kant also makes extensive reference to what he terms “images” that are generated by the imagination. Beyond this, as I argue, images are fundamentally distinct from empirical and pure intuitions. Images and empirical intuitions differ in how they relate to sensation, and all images (even “pure images”) actually depend on pure intuitions. Moreover, all images differ from intuitions in their structure or format. I then turn to a question that naturally arises on the resulting view: if the imagination produces images, and if images are fundamentally distinct from intuitions, then how do intuitions relate to the imagination? I outline reasons for thinking that intuitions and their essential features do not depend on the imagination at all. Though this essay does not decisively argue for this thesis, the resulting view provides a clear account of the distinction between the senses and the imagination in Kant’s theory of sensibility.

Kant famously argues that objects are “given” to us in intuitions and “thought” through concepts, and that both intuitions and concepts are required for “experience” (A50–51/B74–75, A92–3/B125).[1] Kant’s bold claims about the opposition between intuition and concept (and between the faculties of sensibility and understanding) attract perennial philosophical interest and debate, particularly among those interested in Kant’s conception of perceptual experience. However, because of the tendency to focus particularly on the role of intuitions in Kant’s overall picture of perceptual experience, it usually goes unnoticed that besides intuitions, Kant also claims that sensibility produces “images” (Bilder, Einbildungen) and that they are a “product” of the imagination (A141/B181).[2] Though commentators occasionally invoke mental images to explain various aspects of Kant’s philosophy of mind, they tend not to explain what these mental images are or how they relate to Kant’s conception of “image.”[3]

This paper begins by arguing for what I call the Image Thesis. According to the Image Thesis, Kant systematically invokes images (Bilder, Einbildungen) in his central texts, and he claims that images are produced by the imagination. After introducing the textual case for the Image Thesis, I shall advance the stronger Distinctness Thesis: intuitions and images are fundamentally distinct representations— that is, images are qualitatively and numerically distinct representations from intuitions. As we shall see, the Distinctness Thesis has ramifications for Kant’s account of intuition, perception, hallucination, mathematical representation, and mental imagery more broadly.

But once we have established the Image Thesis and the Distinctness Thesis, there is a key lingering question: how do intuitions—representations that are fundamentally distinct from images—relate to the imagination? Are intuitions and images produced by the imagination? In Section 4, I argue that though images depend on and are produced by the imagination, intuitions are independent of the imagination and not produced by it. Call this the No Intuitions Thesis about the imagination. The No Intuitions Thesis is very controversial. Those who reject it span both sides of the aisle in debates about the conceptual or non-conceptual nature of intuitions,[4] as well as recent debates about the metaphysics of intuitions (and in particular, whether intuitions should be understood in a “representationalist”-friendly or “naive realist”-friendly way).[5] Some interpreters even take the claim that the imagination produces intuition (or that the imagination grounds the essential features of intuitions) to be one of Kant’s most characteristic philosophical contributions, and a central part of his theory of space and time.[6]

I do not intend to decisively establish the No Intuitions Thesis in this paper. Doing so would require delving into the great controversies of Kant scholarship, including the territory of the Transcendental Deduction. Instead, in Section 4, I defend the more modest claim that some of the most common motivations for thinking that the imagination produces intuition can be explained away once we accept the Image Thesis and the Distinctness Thesis. Many of the passages in which Kant allegedly claims that the imagination produces intuitions can be read as claiming that the imagination acts on intuitions to produce images. Even though Section 4 leaves significant interpretive and philosophical questions about intuitions unanswered, I think that considering the No Intuitions Thesis a viable interpretive option will help us to better define some of the debates surrounding sensible representation in Kant’s works.

This article thus argues for three claims: the Image Thesis (in Section 1), the Distinctness Thesis (in Sections 2–3), and the No Intuitions Thesis (in Section 4). In all, these three theses give us a blueprint for understanding why the imagination is a special faculty for Kant and how it is different from other faculties of the mind, a point I briefly consider in the concluding Section 5. Exploring the tenability of these theses will help us to better understand how both the senses and the imagination, as the two subfaculties of sensibility, are involved in perceptual experience for Kant.

1. The Image Thesis

As I noted above, some recent readers of Kant claim that he never gave serious consideration to the idea of a mental “image” or “phantasm” distinct from intuition.[7] This section introduces Kant’s theory of images by arguing that Kant invokes images in a systematic way as products of the imagination (the Image Thesis). Moreover, it will motivate my contention explored later that “image (Bild, Einbildung)” is not a mere terminological variant of “intuition (Anschauung).” A theme that emerges, and which I will develop in later sections, is that images are produced by acts of the imagination that are directed at intuitions.

To begin, there is a clear historical motivation for attributing an account of images to Kant. Many of Kant’s direct influences acknowledged the existence of images (Bilder or Einbildungen) as a representational type, and they held that these images were produced by the “power of imagination” or “power to imagine” (Einbildungskraft).[8] Consider Johannes Nikolaus Tetens’s Philosophische Versuche, which Kant read thoroughly prior to publishing the Critique of Pure Reason. In that work, Tetens argues that the representations that the imagination “pull[s] out” from the “outer senses” are called “images” or “phantasmata” (Tetens 1777: 105–106). Furthermore, he claims that these images are distinct from the original sensations from which they are derived, and that images depend on the “power to grasp [Fassungskraft],” which he calls “perception [Perception].” Images are not produced merely from activations of our senses; rather, images are distinct representations produced from such sensory activations, and they can exist even when such sensory activation is no longer present.[9]

Similarly, Kant maintains that the power of imagination (Einbildungskraft) is distinct from sense (Sinn). Like Tetens, he denies that images are the products of mere sensory activation. “The senses,” Kant writes, cannot “produce images [Bilder] of objects” (A120). The senses cannot “put together” or associate different sensations or impressions in the way that imagination can. The imagination is thus left with the task of producing images—a task the intellect itself cannot perform.[10] Like Tetens, Kant also explicitly claims that images can represent objects that are not present—which is unsurprising given Kant’s gloss on the “power of imagination” as “the faculty for representing an object even without its presence in intuition” (B151).[11]

Images as a respresentational type are a centerpiece of Kant’s taxonomy of synthesis in the first Critique. Consider the section headings that announce each synthesis in the A edition of the Transcendental Deduction:

- On the Synthesis of Apprehension in the Intuition [Apprehension in der Anschauung] (A98)

- On the Synthesis of Reproduction in the Image [Reproduktion in der Einbildung] (A100)

- On the Synthesis of Recognition in the Concept [Rekognition im Begriffe] (A103)

Crucial here is that Kant is marking a progression of three representational types: his headings suggest a progression from intuition (Anschauung) to image (Einbildung) to concept (Begriff ).[12] The act of apprehension is “directed at the intuition [auf die Anschauung gerichtet]” (A99).[13] Similarly, in another passage, Kant provides the example that “I make the empirical intuition of a house into perception through apprehension of its manifold” (B162). In this case, apprehension has an “empirical intuition” as its input and a “perception” as its output.[14] So prima facie, the synthesis of apprehension operates on an intuition.

Kant emphasizes the progression from intuition to image later in the A-edition Transcendental Deduction. He claims that the imagination “bring[s]” the “manifold of intuition” into an “image [Bild]” (A120). To bring about this progression from manifold of intuition to image, Kant suggests that the imagination must “take up the impressions” of the senses, that is, “apprehend” those impressions. Kant then invokes the second activity in the progression: apprehension “would bring forth no image [Bild]” without a capacity for “calling back a perception” (A121). Thus, just as the Einbildung involves the synthesis of reproduction, so too does the Bild in this passage involve the “reproductive faculty” of the power of imagination. Both terms denote a single representational type, an image, paired with a particular mental activity, reproduction. What’s more, intuitions and images seem to be distinct parts of the progression that Kant describes in both of these passages.

In the Schematism chapter of the first Critique, Kant turns to the relationship between images and concepts. Consider Kant’s description of a schema as a “representation of a general procedure of the power of imagination for providing a concept its image [Bild]” (A140/B180). Just as we progress from reproduction in the image to the recognition in the concept, so too we progress from an image to the concept that is provided with the image. The schema, in turn, is a representation of some protocol of the power of imagination for providing that image to the concept. Kant notes several sentences later that both images and schemata are “products” of the “productive power of imagination” (A141–142/B181). Furthermore, he claims that images are produced “through” and “in accordance with” schemata.[15] So in the Schematism chapter, Kant invokes images in a way that parallels his taxonomy of synthesis.

In sum, for Kant, the productive power of imagination produces images. Put tersely, the imagination produces mental images (Bilder, Einbildungen) through acts of apprehension and reproduction, and these images accord with schemata.[16] Such images include an “image of a line” (B156), an “image of a triangle” (A141/B180), and an “image of the number five” (A140/B179). In the number case, “if I place [setze]” or apprehend “five points in a row, . . . . ., this is an image of the number five” (A140/B179).[17] Kant also speaks of an “image of a city” and how it is formed when the mind “goes through” and “tak[es] . . . together” the intuitive manifold, which is strikingly similar to how he characterizes apprehension in the first Critique (A99).[18] These observations taken together support the Image Thesis.

2. Images and Empirical Intuitions

We can further unpack the Image Thesis by turning to our defense of the Distinctness Thesis—the claim that intuitions are fundamentally distinct from images. I shall argue for the Distinctness Thesis regarding empirical intuitions by establishing three different claims: first, that empirical intuitions do not depend on images; second, that images can occur in the absence of empirical intuitions; and third, that images differ in their format from empirical intuitions. By the end of this section, we shall see that the combination of these claims entails the Distinctness Thesis.

Since this section begins by considering empirical intuition, we will need a working conception of empirical intuition. For Kant, empirical intuitions are representations that are “related to the object through sensation” (A20/B34). This “undetermined object” of empirical intuition is called an “appearance.” Thus, in every case of empirical intuiting there is an intuited appearance—Kant operates with a distinction between mental acts (or vehicles) and their contents.[19] Humans have two broad classes of empirical intuitions with different contents: outer empirical intuitions of spatial appearances, and inner empirical intuitions of temporal appearances (A22–23/B37). For reasons of space, I will focus on outer intuition in this essay.[20]

2.1. Empirical Intuitions without Images

In order to establish the Distinctness Thesis, our first task is to show that empirical intuitions are independent of and prior to images. As I shall argue, Kant’s account of how empirical intuitions are brought to consciousness suggests that empirical intuitions are prior to and independent of the act of apprehension required for the generation of images.

As an illustrative example of an unconscious intuition, Kant claims that “Newton’s lamellae” that are the hypothesized microphysical basis of color “really are represented, albeit without consciousness, in our empirical intuition.”[21] Thus, according to Kant, whenever we intuit colored objects, our empirical intuitions actually represent the miniscule “lamellae” underlying color. Kant similarly claims that the “field of intuitions of sense [Sinnenanschauungen] and sensations of which we are not conscious” is “immense.”[22] In contrast, “clear” or conscious representations “contain only infinitely few points of this field which lie open to consciousness,” largely because “everything the assisted eye discovers by means of the telescope (perhaps directed toward the moon) or microscope (directed toward infusoria) is seen by means of our naked eyes.” These passages suggest that we do indeed sense objects like “infusoria” (small single-celled organisms) and Newton’s lamellae, and that these items really are represented in “empirical intuition” or an “intuition of sense,” albeit “without consciousness.”

Kant’s overall theory of conscious (or “clear”) representation might strike us today as implausible.[23] But one of the thoughts behind the theory is both plausible and central to his account of empirical intuition: some objects affect our senses, and our empirical intuitions represent those objects, even if we do not notice those objects. Our senses can represent these objects because they are capacities for responding to certain types of objects that affect them—even (perhaps implausibly) very distant or very small objects. In turn, we form empirical intuitions of those objects, “albeit without consciousness.”

But images require an additional activity, namely, that the imagination “take together” those empirical intuitions in a certain way. Kant maintains that the imagination is a “necessary ingredient in perception” (NB: not intuition), and he thinks that it is a mistake to think that the “senses” produce “images” of objects (A120, note). This opens up the possibility that one of the products of the imagination—images—partially explains why we are conscious of certain intuited objects (like dogs and tables) but not others (Newton’s lamellae and distant stars in the Milky Way). If the imagination’s apprehension is directed at empirical intuition and is what makes “perception, i.e., empirical consciousness of it (as appearance), possible” (B160), then some parts of an intuition might not be apprehended at a given time and poised for perceptual awareness. Indeed, the fact that objects are not “perceived with consciousness . . . in no way abolishes their specific property as parts belonging to a merely empirical intuition of the senses.”[24] Thus, some empirical intuitions represent objects that we do not apprehend and consequently do not bring to consciousness.[25] Indeed, Kant chalks up our incapacity to form such conscious representations to our limited “power of imagination,” which is not able to “apprehend [aufzufassen] the manifold of the intuition” of minute objects “with consciousness.”[26] Yet Kant emphasizes that such objects are nevertheless represented in intuition, even though the contents of those intuitions do not stand in the relation to consciousness that Kant calls “perception.”[27]

We would thus lack images of such objects, since images depend on apprehension. Kant himself seems to couch his conclusion in terms of images. He suggests that the fact that we have no image of an object does not show that that object cannot be represented by our sensibility. Eliding the complexities of Kant’s critique of Eberhard, Kant argues that we cannot slide from the claim that (a) we have no “image” of hypothesized objects of metaphysics (like a simple substance or, by extension, Newton’s lamellae) to the claim that (b) those hypothesized objects are “super-sensible.”[28] He says that “it does not at all follow from the fact that no image corresponds to” such hypothesized objects that “their representation is something super-sensible.” For sensibility would still represent such objects through “sensation, hence an element of sensibility.” So Kant is relying on a distinction between two ways of sensibly representing an object, one through images and one through sensation in empirical intuition. His view seems to be that it is simply not the case that in order to represent something sensibly, one must first form an image of it.

The Distinctness Thesis gains further support when we consider that empirical intuitions do not themselves change when they are apprehended or made conscious.[29] Conscious empirical intuitions and unconscious empirical intuitions are not different qua empirical intuition. Just as an “illuminated” and an “unilluminated” wall are not different qua wall, so too are a conscious and an unconscious intuition not different qua intuition. As Kant puts the point, the “consciousness of a representation makes no difference in the specific constitution of the representation; for it can be conjoined with all representations” (UE, 8:217). As an example, “consciousness of an empirical intuition is called perception” (UE, 8:217; cf. Prol, 4:300; B202–203). Similarly, “consciousness is really a representation that another representation is in me.”[30] The clear intuition complex might involve an additional representation beyond the intuition, but the intuition itself does not differ—the difference between a clear and an obscure intuition is the way that consciousness relates to one unchanging intuition.

In Section 2.3, we shall see that the images specify a particular manner in which an intuition is apprehended. And as we have just seen, the manner in which an intuition is apprehended partially determines how (and whether) that intuition is poised to be brought to consciousness or “perception.” As I have argued, the reason we are not conscious of Newton’s lamellae is that our imagination cannot apprehend those minute parts, even though we sense them.[31] Since images depend on this apprehension, they cannot be identical to empirical intuitions that do not themselves change as to their constitution pre- and post-apprehension. Images are better thought of as the content of a representation of those intuitions in consciousness or perception (a point I explain in Section 2.3). For this reason, empirical intuitions do not require images, even if images are involved in relating empirical intuitions to consciousness.[32]

2.2. Images without Empirical Intuitions

The present section turns to the second component of the argument for the Distinctness Thesis: though images depend on empirical intuitions, images can nevertheless occur in the absence of empirical intuitions.

For Kant, it is true that “in order for us even to imagine something as external,” we require “an outer sense” (B276–277n). The “power of imagination” can “impress images [Bilder] upon us” only “in relation to outer sense” (R5653, 18:309). Yet though images depend on both imagination and sense, we can also “immediately distinguish the mere receptivity of an outer intuition [Anschauung] from the spontaneity that characterizes every image [Einbildung]” in virtue of having an outer sense (B276–277n). Kant thus marks off two representational types—“outer intuition” and “image”—and he suggests that outer intuitions involve the “mere receptivity” of outer sense, whereas images involve the “spontaneity” of imagination. Kant repeats this point in notes: “we really distinguish” what he calls an “image [Einbildung]” from “intuitions of the senses [Sinnenanschauungen]” (R6315, 18:621)

Though this point parallels what we already saw in Section 1, Kant also adds that to have an empirical intuition of sense, “the object must be represented as present,” which sets it off from “an image [Einbildung] as intuition without the presence of the object” (R6315, 18:619). Though Kant sometimes refers to “intuition” or “intuitive representation” in a way that encompasses both images and empirical intuitions, I argue that there are fundamental differences between these two representations of sensibility.[33] A key difference is that the object of an intuition of sense is not merely “present,” but “represented as present.” I shall now argue that one representational difference between empirical intuition (or “outer intuition” or “intuition of sense”) and image is that empirical intuitions involve sensations in a way that images do not.

The "organic" senses produce sensations when they are affected by objects.[34] Kant says that “the effect of an object on the capacity for representation, insofar as we are affected by it, is sensation” (A20/B34). Sensations thus are affection-dependent representations. But beyond this affection-dependence, Kant also suggests that sensations play an essential role in our representation of objects as present. “Sensation is that which designates an actuality in space and time” (A374), and sensation “presupposes the actual presence of the object” (A50/B74). Sensation “originates from the presence of a certain object” (LB, 24:235). In several of his works, Kant consistently distinguishes the “power of imagination” that represents objects “even without the presence of the object” (A100; B151) from “sense” as the “the faculty of intuition of the present” or “sensation [sensatio]” (MM, 29:881. Cf. Anth, 7:153; MVo, 28:449; ML2, 28:585; MD, 28:672). Sensations thus play an important role in representing present objects in space and time.[35]

Yet because sensations by themselves do not relate to objects, sensations represent present objects only if suitably involved in empirical intuition.[36] Now these general points suggest a straightforward proposal for how empirical intuitions represent objects “as present”: empirical intuitions involve or contain sensation as a part, whereas images themselves do not involve sensation in the same way. Images (which do not presuppose the presence of their objects) and empirical intuitions depend on sensation in different ways.

Kant denies that the imagination produces new sensations when it produces images. The “power of imagination” is “not creative [schöpferisch], but must get the material for its images [Bildungen] from the senses” (Anth, 7:168. Cf. R314, 15:126). Moreover, “sensations from the senses cannot, in their composition, be made by the power of imagination, but must be drawn originally from the faculty of sense” (Anth, 7:168). Even though the imagination can be “productive,” the “material” of its representations must first be “given to our faculty of sense” (Anth, 7:168). So if one has never had a sensation of red by having one’s senses affected by an object, then one’s imagination cannot generate such a sensation, even by “composition.” That is what it means to say that the power of imagination is not “creative.”

When we unpack Kant’s account of image production, we find evidence not only that the imagination does not produce new sensations, but that it does not produce sensations full stop. In turn, images would then not involve sensation production but, instead, something like “copies” or “traces” of previously produced sensations. As a historical motivation for this reading, we can again turn to Tetens, who claims that “representations of sensation [Empfindungsvorstellungen]” or “images” are obtained from sensations, and are produced when the imagination takes up “traces” of sensations. He explicitly claims that these images can outlast sensation, such that images can occur “without the sensation being present” (Tetens 1777: 23). Given Kant’s positive appraisal of Tetens’ account of perceptual psychology (R4900, 18:23), it would not be surprising if Kant simply agreed with Tetens on this point.

Moreover, in his discussion of perceptual hallucination and illusion in the Anthropology, Kant claims that “illusions [Täuschungen]” involve “taking images [Einbildungen] for sensations [Empfindungen]” (Anth, 7:161). So illusions involve confusing images and sensations. Plausibly, taking an image to be a sensation is a confusion because images are not sensations or composed of sensations. Otherwise, the mistake that Kant describes would not be a mistake at all—the subject would not be wrong in taking images for sensations if images themselves were composed of sensations.[37] Illusions do indeed involve images that represent outer sensory qualities in virtue of containing traces of sensation (illusions are not merely pathological belief states), but the subject need not simultaneously undergo a sensation to have such images.

The images in dreams also do not contain sensations as parts. In his precritical Dreams of a Spirit Seer, Kant provides an account of daydreaming on which daydreaming (of “waking dreamers”) differs from regular dreaming.[38] He claims that though the “images in question may very well occupy” a daydreamer, they still “will not deceive him” (TG, 2:343). The daydreamer is not deceived because he can differentiate “his fantastical images [Bilder] as hatched out by himself” from “the real sensation [wirkliche Empfindung] as an impression of the senses.” Yet when the subject falls asleep, the external senses are no longer affected by objects, and “all that remains are the representations he has created himself.” As a result, when we dream, we are deceived by our images. On Kant’s view, the confusion of images and sensations arises because “there is no sensation which allows” the subject, “by comparing” the “real sensation” with the illusory image, to distinguish self-made phantoms from sensations.

In short, our imagination can “invent [erdichten] something for ourselves, but this is not a sensation” (LB, 24:235–236). For instance, suppose I am having a sensation of red while imagining green in a daydream. I have a sensation of red and an image of green. According to Kant, when I am in this daydream, I do not have the task of sorting out a heap of occurrent sensations, some of which (green sensations) are produced by the imagination, others of which (red sensations) are produced by the senses. Instead, the asymmetry between real sensations and images that lack sensations facilitates the distinction between occurrent sensing and occurrent imagining. As another example, when I entertain a mental image of a pirate, I might represent a rough masculine face, the characteristic hat, and the eye patch. But suppose I imagine his shirt in only very coarse detail. If someone asks me how many buttons are on his shirt, it is not as if I have a sensation array available to me, on the basis of which I could apprehend how many buttons there “really” are. There are as many buttons as I imagine there to be. These examples illustrate what I take to be the hallmark of Kant’s account, namely, that I am able to realize that I am engaging in mental imagery by comparing my mental images with actual sensations that I enjoy.

Empirical intuitions thus involve sensations in a way that images do not.[39] As a result, empirical intuitions represent objects “as present” in a way that images do not. So not only are empirical intuitions prior to and independent of images, but images are also seem to be possible when we lack sensation-involving empirical intuitions that represent present objects. This “double-dissociation” of the images and intuitions from one another suggests that they are fundamentally distinct.

2.3. The Structure of Images and Intuitions

The third point in favor of the Distinctness Thesis is that images and empirical intuitions differ qualitatively in their compositional structure. As I shall now argue, the format of images stand in a many-to-one relation to the format of intuitions, and this difference in format entails a difference in content. This section will bring together our previous discussion by showing how images arise when empirical intuitions are “determined” by the power of imagination, and it will help us see a fundamental continuity between empirical images and pure images, to which I turn in the next section.

Since apprehension and reproduction are the two central activities of image production, it is not surprising that apprehension and reproduction jointly account for the structure of images. Kant describes apprehension as a “running through” and “taking together” of the “manifoldness” of intuition (A99), as well as a “placing together” or “composition [Zusammensetzung]” of the parts of an intuition (B160), or a “positioning together” or “juxtaposition [Zusammenstellung]” of the parts of an intuition (A176/B219). These glosses suggest that apprehension is part of a specialized grouping or perceptual organization procedure.[40] Apprehension is required to generate representations of groupings—without apprehension, the manifold parts given in intuition would not be “represented as such” (A99).[41]

Prior to apprehension, the intuition itself is not grouped, “composed,” or “determined” in Kant’s sense. Kant often claims that the inputs to apprehension are “undetermined,” as when he claims that an appearance is the “undetermined object [unbestimmte Gegenstand] of an empirical intuition” (A20/B34).[42] Yet he also claims that these undetermined contents can be “determined” by the imagination, which is the “faculty for determining sensibility a priori” (B152). As a result, we have what Kant calls at one point a “determinate intuition [bestimmte Anschauung]” (B154).[43] As I argued in the case of clear intuition, we need not think of determined intuition as a modification of the intuition itself; we can instead think of “determination” as producing something from the intuition or adding something to it. So the claim that a “determinate intuition” depends on the synthesis of apprehension or the imagination does not imply that apprehension produces intuitions full stop. Images are a natural candidate for what is produced from intuition. Indeed, one of Kant’s examples of “determining” an intuition is the “drawing” of an “image [Bilde] of a line” (B156). I want to suggest that once the imagination brings together the manifold in a particular way, it generates an image that represents that manifold “as such.” The image that is generated from an intuition determinately represents the content of the intuition (the appearance).

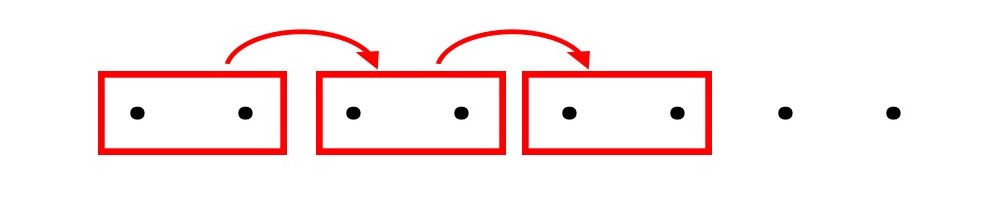

A concrete instance of this determinate representation involves the representation of relations between parts of the appearance (that is, “groupings”). Take the example of an image of six (cf. Section 1). Kant claims that we have a schema “through which” such an image becomes possible—namely, the schema that indicates the procedure that we know as counting.[44] The procedure that the schema specifies has two basic components. First, the imagination has to select some unit to iterate.[45] Suppose it selects a dot as its unit. Second, the imagination has to apprehend this unit several times—the imagination treats all dots as of the same kind but as spatially differentiated. This means that the given representation in Figure 1 is to be treated as a group of objects that are of the same kind (in Kant’s terminology, they are “homogeneous”), each of which is a unit (no dot can be “double-counted”). Figure 2 diagrams the apprehension of the dots.

The intuition in Figure 1 represents items in space,[46] while the image of six in Figure 2 represents those items in a determinate manner. The red arrows denote the activity of successive apprehension. When apprehension moves to a dot (say, the fourth dot from the left, in the act symbolized by the third arrow from the left), the imagination simultaneously reproduces the previously apprehended dots (i.e., those contained in the three left-most boxes). Apprehension successively grasps each unit, and reproduction reproduces the apprehended units while further units are being grasped. The representation symbolized by the red boxes is the image.

As Kant writes in his Preisschrift, “the representation of the composite [Zusammengesetzten], as such, is not mere intuition, but rather requires the concept of composition, insofar as it is applied to intuition in space and time” (FM, 20:271. Cf. R6360, 18:688). On the proposed model, apprehension is the activity that introduces a “representation of the composite” that is not present in the “mere intuition.” Unlike the mere intuition, the image reflects a particular way of composing the intuition. In contrast, uncomposed or “mere” intuitions can be composed in countlessly many ways, corresponding to the many images we can form from them. And this one-to-many relationship between the mere uncomposed intuition and the image is grounded in the sytheses of apprehension and reproduction: apprehension selects which units to apprehend (e.g., it doesn’t apprehend non-dots), while reproduction reproduces the units relevant to the image in question (e.g., it doesn’t reproduce items the imagination apprehended yesterday that are unrelated to the present image). Without both processes, an image of six could never arise.

To see the one-to-many relationship between intuitions and images, note that the imagination could have used two dots as the “unit” measure, and then produced an image of 3 by apprehending three pairs of dots, as in Figure 3.

This discussion illustrates that a single uncomposed intuition corresponds to multiple possible images. For the intuition (Figure 1) is compatible with at least two different ways of “carving” or “grouping” the manifold (Figures 2 and 3). In one case, an image of three is produced; in another case, an image of six is produced. The image that the imagination generates depends on which unit it selects, and how many times it iterates that unit.

Therefore, the representational format of images does not supervene on the representational format of intuitions in two respects. On the one hand, which image the imagination forms is not determined by the intuition, since there is a one-to-many relationship between an intuition and the images it is possible to form from that intuition. On the other hand, the structure of even a single image is not determined by the intuition. For apprehension and reproduction play an essential role in structuring an image: apprehension is directed at the intuition in selecting certain units, while reproduction is required to selectively reproduce certain previously apprehended units. In short, the structure of images is not determined by the structure of intuitions alone.

If the above account is correct, then images are representations with a special structure. To echo Fodor (2007), the image has a specific or “canonical” composition.[47] That is, just like the sentence ‘Karpov is in the yard’ has a special “canonical” way of being composed and decomposed—namely, into ‘Karpov’ and ‘is in the yard’ (and not into ‘Karpov is in’ and ‘the yard’)—so too do images need to be composed and decomposed in a certain way rather than another. The explanation for why images have a certain structure—why an image of six arises instead of an image of three—depends on what determines the “canon” of composition. The matter becomes complicated once we try to consider why the human imagination forms (say) rabbit-shape images and not (say) two-legs-and-one-ear images. Though I will not settle the question here, there seem to be two different approaches. On the one hand, perhaps images have the structure they do merely because of features of the imagination independent of the understanding.[48] On the other hand, perhaps the structure of (at least some) images also depends on the understanding.[49] Broadly speaking, these two options reflect a “bottom-up” and a “top-down” explanation of the etiology of images, respectively. Deciding for either model is a task for further research.[50] But on both models, two different images could result from the same undetermined intuition.[51]

This account can be applied to everyday perceptual cases. Kant notes that it takes a special effort of the imagination to “illustrate” the complex manifold that is given in intuition.[52] Even the mundane case of perceiving an apple has this structure. The image takes together particular parts of the intuited appearance— say, the shape of the apple’s stem and the apple’s redness—and represents them in an image. I might not apprehend a small blemish on the apple, or notice one of its dimples—I might not represent those features in an image—even though I intuit those features.[53] The image might also represent features that are not present in the empirical intuition (like the apple’s backside or its juiciness, assuming that I am not tasting it). In short, the empirical intuition still represents the apple and objects in the space surrounding it through sensation, but the empirical intuition does not represent any particular way of relating the spatial features to one another, nor does it represent absent features. Moreover, this same model could be applied to non-spatial inner intuition: apprehension could group the intuition of a musical melody into distinct “phrases,” insofar as tempo and rhythm are parts of the temporal form of the music. We can also form images of “the time from one noon to the next” by grouping together a certain sets of episodes or moments (A102).

I thus think that we should understand a “determinate intuition” as a complex of an (uncomposed) intuition and an image produced from it.[54] As in the case of clear or conscious empirical intuition, the empirical intuition does not itself change during the process of determination; the spatially ordered manifold of sensations is not altered between various ways of composing that manifold. Rather, the additional representational structure is an image distinct from that empirical intuition; moreover, in virtue of this added structure, new contents (e.g., “three”) are generated that have images as their vehicles.[55] An image is not merely a set of empirical intuitions, but a distinct representation of the contents of an intuition. After all, I take it that it is an interpretive desideratum that the imagination produces some new representation through its activities, given Kant’s claim that apprehension and reproduction “generate” a “representation” of spatial and temporal objects (A99–101). Moreover, Kant also claims that the imagination’s synthesis generates “a certain content [Inhalt]” that is not had by the manifold of intuition itself (A78/B103). Images are the fundamentally distinct representations that have such contents.

To conclude, there is a representation—an image—distinct from the empirical intuition that (a) has new representational contents and that (b) does not depend on the presence of the object of the empirical intuition. This is a general model that needs to be worked out further. But these considerations show how the imagination apprehends intuition and reproduces what it has previously apprehended in order to generate an image. As a result, the structure of images depends not only on intuition, but also on the synthesis of the imagination.

3. Images and Pure Intuition

Even if images are fundamentally distinct from empirical intuitions, the Distinctness Thesis might still be false. For Kant might be committed to the claim that pure intuitions are images. In this section, I contend that the pure intuition of space described in the Metaphysical Expositions of the Transcendental Aesthetic—the “pure” representation of an “infinite given magnitude” with a whole-prior-to-part structure—is not an image. Nevertheless, Kant does recognize a central role for an imagistic representation of space. But I suggest that this “pure image” of space is fundamentally distinct from and depends on the pure intuition of space.[56]

It is well known that Kant discusses “pure intuitions” of space and time at length, particularly in the Transcendental Aesthetic, the crucial first division of the Critique. Less well known is that Kant does indeed speak of “pure images” in the Schematism of the first Critique. He writes that “the pure image of all magnitudes (quantorum) for outer sense is space; for all objects of the senses in general, it is time” (A142/B182; cf. A320/B377). Though some interpreters have explicitly equated pure images and pure intuitions,[57] I think there are at least three reasons that Kant meant to consider them fundamentally distinct.

First, some have argued (to my mind convincingly) that the understanding, due to its discursive nature, could not in principle produce the pure intuition of space.[58] We can adapt this argument about discursivity into an argument about the nature of image production. Consider the processes of apprehension and reproduction on which image production depends. According to Kant, apprehension is successive and goes from part to whole (see A162–163/B203–204, A182/B225).[59] But Kant’s claims about the pure intuition of space seem to be just the opposite: we are given space all at once, and the “single all-encompassing” and “essentially single” space is prior to its parts (A25/B39). Image production depends on part-before-whole apprehension, whereas the pure intuition of space is a whole-before-part representation. As a result, our pure intuition of space cannot itself be an image: it cannot be an output of image production.

A second reason to distinguish the “pure image” of space from the pure intuition of space is that images and pure intuitions are grounded in different faculties of the mind. In his response to Eberhard, Kant provides a crucial correction to Eberhard’s conception of pure intuition:

Where have I ever called the intuitions of space and time, in which images [Bilder] are first of all possible, themselves images (which always presuppose a concept of which they are the exhibition [Darstellung], e.g., the indeterminate image for the concept of a triangle, wherein neither the ratios of the sides nor those of the angles are given)? . . . The ground of the possibility of sensory intuition is neither of the two, neither limit of the cognitive faculty nor image [Bild]; it is the mere receptivity peculiar to the mind, when it is affected by something (in sensation), to receive a representation in accordance with its subjective constitution. (UE, 8:222; see also UK, 20:422)

Kant denies in this passage that our “intuitions of space and time” are “themselves images.” He explains that it is sensibility in its “mere receptivity” that is the “ground of” these intuitions of space and time. Kant emphasizes this point in one of his essays: “what is subjective in the formal constitution of sense, as receptivity for the intuition of an object, is alone [allein] that which makes possible a priori, i.e., in advance of all perception, an a priori intuition” (FM, 20:267, emphasis added). Kant suggests in both of these passages that sensibility in its non-spontaneous guise (as “sense” or “mere receptivity”) grounds the features of the pure intuition of space. Yet as we saw above, the imagination implicates the active (not merely receptive) facets of sensibility, including the synthesis of the imagination in its “productive” guise. If Kant intended for image production to explain how essential features of the pure intuitions of space and time arise, then it is unclear why he chose to emphasize the merely receptive aspect of sensibility in these passages. After all, for Kant, the senses cannot produce images (A120n), and the features of images depend on activities of the imagination that go above and beyond the senses. So the pure image of space is grounded on different faculties and mental activities from the pure intuition of space.[60]

As anticipated in the previous passage, a third reason to distinguish the pure image of space from the pure intuition of space is that pure intuitions ground images. Again in reference to Eberhard, Kant considers and rejects the view that space as a whole is an image of the same kind as an image of a triangle:

For [Eberhard] understands by imagistic [Bildlichen] not something like the figure in space as geometry would view it, but space itself (although it is hard to understand, how one could form an image [Bild] of something external to oneself without presupposing space)[.] (UK, 20:422–423)

This passage implies that the pure intuition of space is not an “image of something external to oneself.” For images of outer objects “presuppos[e]” space. So to have an image of something external to oneself, one must already possess a pure intuition of space.

These three considerations suggest that the pure image of space is fundmentally distinct from the pure intuition of space. Now one might suspect that Kant was being imprecise in his mention of a “pure image” in the Schematism.[61] On the contrary, I think that there is a way of seeing the distinct “pure image” of space as a unique cog in the machinery of the Schematism, which I will only sketch here.

In his essay on Kästner’s treatises, Kant distinguishes two representations of space in a way that I think directly maps onto the distinction I propose between a pure intuition and a pure image. He claims that “metaphysics” shows how one can “have” the original representation of space, whereas “geometry” teaches how one can “describe” a space (UK, 20:419). In metaphysics, one considers how space is “given” as an “original” space, whereas in geometry, one considers how a space is “made” or “derived” from this originally given space. Kant then consolidates this distinction between metaphysical and geometrical doctrines of space by drawing a distinction between two different representations of space, which he calls “subjectively given space” and “objectively given space.” For Kant, “the metaphysically, i.e. originally, nonetheless merely subjectively given space . . . consists in the pure form of the sensible mode of representation of the subject, as a priori intuition” (UK, 20:420–421). So subjectively given space is itself a representation, that is, a pure "a priori intuition."

Thus, Kant makes a distinction between “metaphysical” or “subjectively given” space and “geometrical” or “objectively given” space. Now my suggestion is that subjectively given space is a non-imagistic representation of space, whereas objectively given space is an imagistic representation of space. The pure image of space—objectively given space—is a representation of space produced on the basis of the pure intuition of space—subjectively given space.[62] If objectively given space is equated with the pure image of space, then it is not surprising that “geometrically and objectively given space is always finite” (UK, 20:420). For images are produced by successive apprehension and reproduction procedures—procedures which are themselves finite activities (the imagination cannot apprehend an infinite quantity of items). Our imagistic representation of space represents a finite space, whereas our non-imagistic representation of space represents infinite space. This observation blocks the possibility that the pure intuition of space becomes the pure image of space, since the pure intuition of space does not become finite—it remains infinite.

Though a full account of the pure image of space would need to take into account Kant’s understanding of geometric construction,[63] we at least have the resources to make sense of why Kant invokes the pure images of space and time in the Schematism. The topic of the Schematism is the “subsumptio[n] of an object under a concept” (A137/B176). Recall too that a schema is a “representation of a general procedure of the imagination for providing a concept with its image” (A140/B179). So Kant’s thought is that in order for spatial objects to be subsumed under concepts, the imagination must produce an imagistic “objectively given” representation of space.[64] For instance, if I “place” three lines mutually orthogonally to one another in space, then I am carving space into three distinct dimensions (see B154).[65] This is a pure image of space with canonical compositionality; the pure image explicitly represents three-dimensional (not two-or four-dimensional) space. So subsumption requires that the imagination produce “objectively given space”—and this product relies on the pure intuition of space or “subjectively given space.”

4. Defending the No Intuitions Thesis: A Sketch

In the previous sections, I argued that Kant accepts the Image Thesis and the Distinctness Thesis. For him, the imagination produces images, and images are fundamentally distinct from both pure and empirical intuitions. We will now turn to the controversial No Intuitions Thesis, according to which the imagination does not produce intuitions of any kind.

The No Intuitions Thesis is a natural complement to the Image and Distinctness Theses. For if the imagination produces images via the apprehension and reproduction of intuitions, and if these images are not intuitions, then the imagination cannot also produce intuitions via these same processes of apprehension and reproduction. Instead, the senses are a natural candidate for the original producers of intuition. Kant does after all claim that “it is the business of the senses [Sinne] to intuit; that of the understanding, to think.”[66] Nevertheless, there are some initially compelling reasons to think that the imagination produces intuitions or grounds their essential features. My goal in this section is to show that once we appreciate the Image and Distinctness Theses, many of Kant’s central texts on the imagination admit of a reading that is compatible with the No Intuitions Thesis.

4.1. Empirical Representation: Memory and Hallucination

To take our first case, Kant maintains that the imagination is involved in memory and recollection of previous representations (e.g., Anth, 7:182). As Kant puts it, the “reproductive imagination” can “bring back into the mind an empirical intuition had previously” (Anth, 7:167). There are (at least) two different ways of cashing out this statement. On the first model, empirical intuitions are “reproduced” in the way that a copy machine copies an original paper. The copy is not itself the original empirical intuition. Perhaps all that is preserved is an image formed from the empirical intuition, not the empirical intuition itself.[67] On the first model, an image or some copied representation figures into a state that allows us to remember the episode (perhaps accompanied by various beliefs that link the image to a particular episode).[68] On the second model, to “reproduce” an empirical intuition is to bring the same intuition “back into mind,” just as I “re-produce” the same (non-counterfeit!) driver’s license every time an airport agent asks for it. On this view, the empirical intuition is stored, not a copy of it.

The key point is that neither view of memory requires that empirical intuitions depend on the imagination for their production, even if their preservation or reproduction requires the imagination.[69] Even if an empirical intuition could be preserved after its object is absent, this would not show that empirical intuitions (or any of their features) depend for their generation or production on the imagination.

However, cases of mental imagery and hallucination pose a special challenge to the No Intuitions Thesis. The objection goes like this. Suppose I imagine a dog with three horns, even though I am not sensing and have never sensed a dog with three horns. I could similarly hallucinate this object. In these cases, the imagination actively recombines sensory qualities to represent an object that I have never seen before. But here’s the rub, so goes the objection: when I am imagining the dog’s brown body and its red horns, I am producing a new empirical intuition, because my imagination is recombining red and blue sensations into a new spatial configuration. Moreover, Kant adds that the representation of such a dog in hallucination has the same “quality” in both “truth and dream” (Prol, 4: 290), such that we should deny that “every intuitive representation” entails the “existence” of an outer object (B278).[70]

But Kant’s texts on these points allow that an image, as a “mere effect of the imagination,” is the common element in veridical and non-veridical cases (B278). As explained in Section 2.2, the image itself would not involve sensation production in the way that empirical intuitions do, but instead would involve rearrangements of traces of previously produced sensations.[71] Thus the No Intuitions Thesis can make sense of Kant’s suggestion that empirical intuitions “would depend immediately on” or “presuppose” the “presence of an object,” while allowing that some intuitive representations like images lack this dependence (see Prol, 4:281). For Kant does not think that images have this same dependence on present objects that empirical intuitions do. At the same time, there is a qualitatively identical representation of the object—an image—that can be entertained in both veridical and non-veridical perception.[72]

4.2. Pure Representation: Spaces, Times, and Exhibition

As I began to argue in Section 3, there are a variety of ways that Kant seems to deny the imagination a substantive role in the production of the pure intuitions of space and time. To repeat, Kant thinks that “the formal constitution of sense”—not the imagination—is “alone [allein] that which makes possible a priori, i.e., in advance of all perception, an a priori intuition” (FM, 20:267, emphasis added). Similarly, in the Transcendental Aesthetic of the Critique, Kant denies that space and time are “creatures of the power of imagination [Geschöpfe der Einbildungskraft]” (A40/B57). And Kant explains this claim by invoking images: if geometry merely described a “creature” of the imagination, then Kant thinks it is unclear “how things would have to agree necessarily” with such an “image [Bilde] that we form of them by ourselves and in advance” (Prol, 4:287). But Kant claims precisely this for our pure intuition of space: objects do necessarily agree with the intuition of space that we form prior to encountering those objects.

Still, some of Kant’s texts seem to stand in tension with the No Intuitions Thesis about the imagination. Kant does indeed claim that without apprehension by the imagination, “we could have a priori neither the representations of space nor of time” (A100). Yet when Kant claims that the imagination is required for these “purest” and “most fundamental” representations of space and time, he does so in his argument for the claim that apprehension and reproduction are required for such representations (A100, A102). Since Kant claims that “apprehension” is “directed at the intuition” (A99), it would be odd if these “representations” of space and time were themselves the pure intuitions of space and time. Kant’s examples actually seem to tell against this identification: his examples of representations of space and time are “a line,” “one noon to the next,” and “a certain number” (A102). These three “representations” are plausibly examples of images (see Tolley 2016: 277–279). Therefore, this passage does not spell trouble for the No Intuitions Thesis.

Kant also claims that space is an “ens imaginarium” (A291/B347). Let’s stipulate that this passage is indeed meant to assert that space in some sense depends on the imagination. This claim comes in the final paragraph of the Transcendental Analytic, where Kant draws up a table of the “concept of nothing,” which is a species of the “concept of an object in general” (A290/B346). So more specifically, Kant seems to be saying that space, considered as an “object in general,” depends on the imagination.

There is evidence in this passage that space considered as “object” refers to the pure image of space, not the pure intuition. When Kant unpacks his conception of an ens imaginarium, he claims that space is an ens imaginarium because “if extended beings were not perceived [wahrgenommen], one would not be able to represent space” (A292/B349). The fact that Kant seems to be asserting that our ability to represent space depends on our perception of objects suggests that he is talking about an imagistic representation of space. For Kant insists that the (non-imagistic) pure intuition of space itself is not a perception (A165/B207), and that it does not depend on perception (B41). So Kant must be referring to space represented “objectively” and imagistically in this passage. This objective representation is plausibly the pure image of space, not the pure intuition of space.

A similar response on behalf of the No Intuitions Thesis could be made regarding Kant’s claim that the “unity” of a formal intuition “presupposes a synthesis” (B160n). In this heavily contested passage, Kant is marking two ways that space is “represented a priori” (B160). And he specifically claims that the “unity” of the “formal intuition” ultimately “presupposes a synthesis” (B160n), even though the “form of intuition” (which Kant himself calls a “pure intuition,” A20/B34) does not presuppose such a synthesis. It is the formal intuition that involves “space, represented as object (as is really required in geometry).” In line with Section 3, Kant likely has in mind an “objective” representation of space involved in geometry that he associates with the imagination’s synthesis and image formation, and which contrasts with the “subjective” original pure intuition of space.[73]

Now it cannot be denied that Kant very closely associates pure intuition with the imagination, particularly under its “productive” guise: “pure intuitions of space and time belong to the productive faculty” of imagination.[74] But a proponent of the No Intuitions Thesis can point to a key elucidation, namely, that the imagination is “productive” because it is “a faculty of the original exhibition [Darstellung] of the object (exhibitio originaria).” Plausibly, exhibition (Darstellung) is not merely a synonym for intuition (Anschauung) of an object. Kant often confusingly associates the idea of “giving” an object with both exhibition and intuition. Intuitions give objects to the mind. In contrast, images and the imagination are involved in “giving” a “corresponding intuition to the concepts of the understanding” (B151). But this latter sense of “give”—giving an object to a concept instead of to the mind—is a fundamentally distinct notion for Kant. Exhibition is this activity of giving an object to a concept, whereas intuition is the activity of giving an object to the mind (see A240/B299, A713/B741). And Kant associates exhibition with images when he claims that “concepts of number equally require pure sensible images [Zahlbegriffe bedürfen eben so reinsinnlicher Bilder]” (AA, 14:55). One can thus understand the pure intuitions of space and time as “sketch pads” given to the mind on which we “draw” images of certain shapes and numbers; such an activity of drawing “exhibits” features of space that the pure intuition alone does not exhibit.[75]

To bring this discussion to a close, we should hold apart three different things that are not equivalent for Kant: (a) space itself, (b) parts of space (the “manifold” of spaces), and (c) objects in space. One way to understand Kant’s claims that is consistent with the No Intuitions Thesis is that the imagination produces neither space nor the manifold of spaces. The senses, not the imagination, produce the pure intuition of space and provide the manifold of spaces.[76] Though this is not the final word on pure intuition in Kant, I hope this model clarifies what opponents of the No Intuitions Thesis need to argue. The No Intuitions Thesis allows that the imagination is required to represent determinate objects in space—objects like squares and triangles. But the No Intuitions Thesis denies both (a) that essential features of the pure intuitions of space depend on the imagination and (b) that the imagination produces the manifold of spaces. As I argued in Section 3, facts about image production seem ill-equiped for challenging the No Intuitions Thesis on either of these points. So appealing to image-producing procedures of the imagination in such an argument is not a promising strategy for challenging the No Intuitions Thesis.

5. Conclusion

This essay argued that for Kant, the imagination generates images (the Image Thesis) and that these images are fundamentally distinct from empirical and pure intuitions (the Distinctness Thesis). Moreover, these two theses complement the claim that the imagination does not generate intuitions at all (the No Intuitions Thesis). As I noted in the introduction, a full defense of the No Intuitions Thesis would need to incorporate an account of the Transcendental Deduction, since many interpreters find in this section of the first Critique the strongest philosophical considerations for thinking that the imagination must actually produce intuitions (usually because they think the understanding plays a role in the generation of intuition). Nevertheless, Section 2.3 provided a sketch of the imagination’s “determination” function that serves as a starting point for an account of the Transcendental Deduction friendly to the Image Thesis, Distinctness Thesis, and No Intuitions Thesis.[77]

The Image Thesis and Distinctness Thesis raise several questions for further investigation, and I’ll note three. First, there is the general question of what the different functions of images and intuitions are in cognition (Erkenntnis) of various kinds.[78] Broadly speaking, intuitions and the senses figure into the explanation of how finite subjects can be related to objects in the first place, whereas images and the imagination figure into the explanation of how intuited objects can be “determined” and, ultimately, related to concepts. But the precise sense in which a particular cognition depends on actual image formation remains an open question. Second, and relatedly, more work is required to determine how schemata relate differently to images, on the one hand, and intuitions, on the other. Given the diversity among schemata, it is possible that some schemata depend on images (or intuitions), while some images depend on schemata. Finally, there remains the question of how precisely images depend on consciousness or vice versa; similarly there remains the question of how precisely images depend on concepts or vice versa. And again, given the diversity of empirical, mathematical, and philosophical concepts that Kant invokes, it is possible that there will be no one-size-fits-all answer to this question.

However these questions play out, the present essay provided a clearer conception of the contribution that the imagination—as distinct from sense—makes to sensibility. The contribution of sensibility to human cognition relies on a complex interweaving of both sense and imagination, and adequately understanding this relationship requires us to take into account Kant’s theory of images.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Max Edwards, Claudi Brink, Rosalind Chaplin, Lisa Shabel, Lucy Allais, Eric Watkins, and especially Clinton Tolley for their invaluable comments on early drafts of this paper. The helpful feedback from three anonymous reviewers for this journal greatly improved the final version. I would also like to thank Johannes Haag, Michael Oberst, and Ayoob Shahmoradi for extensive discussion on various topics addressed in this paper.

Abbreviations

Anth = Anthropologie in pragmatischer Hinsicht

FM = Preisschrift über die Fortschritte der Metaphysik

JL = Jäsche Logik

KU = Kritik der Urteilskraft

LB = Logik Blomberg

MD = Metaphysik Dohna

MK 2 = Metaphysik K 2

ML 1 = Metaphysik L 1

ML 2 = Metaphysik L 2

MMr = Metaphysik Mrongovius

MVi = Metaphysik Vigilantius

MVo = Metaphysik Volckmann

Prol = Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik, die als Wissenschaft wird auftreten können

R = Reflexionen

TG = Träume eines Geistersehers, erläutert durch Träume der Metaphysik

UE = Über eine Entdeckung, nach der alle neue Kritik der reinen Vernunft durch eine ältere entbehrlich gemacht werden soll

UK = Über Kästners Abhandlungen

References

- Allais, Lucy (2009). Kant, Non-Conceptual Content and the Representation of Space. Journal of the History of Philosophy, 47(3), 383–413.

- Allais, Lucy (2015). Manifest Reality: Kant’s Idealism and His Realism. Oxford University Press.

- Allais, Lucy (2017). Synthesis and Binding. In Anil Gomes and Andrew Stephenson (Eds.), Kant and the Philosophy of Mind (25–45). Oxford University Press.

- Axinn, Sidney (2013). Symbols, Mental Images, and the Imagination in Kant. In Michael L. Thompson (Ed.), Imagination in Kant’s Critical Philosophy (97–104). De Gruyter.

- Baumgarten, Alexander (2013). Metaphysics: A Critical Translation with Kant’s Elucidations, Selected Notes, and Related Materials. Bloomsbury.

- de Sá Pereira, Roberto Horácio (2017). A Nonconceptualist Reading of the B-Deduction. Philos Stud, 174(2), 425–442.

- Falkenstein, Lorne (1995). Kant’s Intuitionism. A Commentary on the Transcendental Aesthetic. University of Toronto Press.

- Fodor, Jerry A. (2007). The Revenge of the Given. In Brian P. McLaughlin and Jonathan D. Cohen (Eds.), Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Mind (105–116). Blackwell.

- Friedman, Michael (2013). Kant’s Construction of Nature. A Reading of the Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science. Cambridge University Press.

- Ginsborg, Hannah (2008). Was Kant a Nonconceptualist? Philosophical Studies, 137(1), 65–77.

- Ginsborg, Hannah (2015). The Normativity of Nature. Oxford University Press.

- Golob, Sacha (2014). Kant on Intentionality, Magnitude, and the Unity of Perception. European Journal of Philosophy, 22(4), 505–528.

- Golob, Sacha (2016). Why the Transcendental Deduction Is Compatible with Nonconceptualism. In Dennis Schulting (Ed.), Kantian Nonconceptualism (27– 52). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gomes, Anil (2014). Kant on Perception: Naïve Realism, Non-Conceptualism, and the B-Deduction. Philosophical Quarterly, 64(254), 1–19.

- Gomes, Anil (2017). Naïve Realism in Kantian Phrase. Mind, 126(502), 529–578.

- Grüne, Stefanie (2009). Blinde Anschauung. Klostermann.

- Grüne, Stefanie (2016). Sensible Synthesis and the Intuition of Space. In Dennis Schulting (Ed.), Kantian Nonconceptualism (81–98). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grüne, Stefanie (2017). Are Kantian Intuitions Object-Dependent? In Anil Gomes and Andrew Stephenson (Eds.), Kant and the Philosophy of Mind (67–85). Oxford University Press.

- Haag, Johannes (2007). Erfahrung und Gegenstand. Das Verhältnis von Sinnlichkeit und Verstand. Vittorio Klostermann.

- Horstmann, Rolf-Peter (2018). Kant’s Power of Imagination (Vol. 13). Cambridge University Press.

- Indregard, Jonas Jervell (2018). Consciousness as Inner Sensation: Crusius and Kant. Ergo, 5(7), 173–201.

- Jankowiak, Tim (2014). Sensations as Representations in Kant. British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 22(3), 492–513.

- Knauff, Markus (2013). Space to Reason: A Spatial Theory of Human Thought. MIT Press.

- Kraus, Katharina Teresa (2013). Quantifying Inner Experience?—Kant’s Mathematical Principles in the Context of Empirical Psychology. European Journal of Philosophy, 24(2), 331–357.

- Land, Thomas (2016). Moderate Conceptualism. In Dennis Schulting (Ed.), Kantian Nonconceptualism (145–170). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Langton, Rae (1998). Kantian Humility: Our Ignorance of Things in Themselves. Oxford University Press.

- Longuenesse, Beatrice (1998). Kant and the Capacity to Judge: Sensibility and Discursivity in the Transcendental Analytic of the Critique of Pure Reason. Princeton University Press.

- Longuenesse, Beatrice (2005). Kant on the Human Standpoint. Cambridge University Press.

- Makkreel, Rudolf A. (1994). Imagination and Interpretation in Kant: The Hermeneutical Import of the Critique of Judgment. University of Chicago Press.

- Matherne, Samantha (2015). Images and Kant’s Theory of Perception. Ergo, 2(29), 737–777.

- McLear, Colin (2015). Two Kinds of Unity in the Critique of Pure Reason. Journal of the History of Philosophy, 53(1), 79–110.

- McLear, Colin (2016). Concepts, Intuitions, and Structure. Paper presented at the Pacific Meeting of the American Philosophical Association.

- McLear, Colin (2017). Intuition and Presence. In Anil Gomes and Andrew Stephenson (Eds.), Kant and the Philosophy of Mind (86–103). Oxford University Press.

- Michaelian, Kourken and John Sutton (2017). Memory. In Edward N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 ed.). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/memory/

- Nanay, Bence (2009). Perception and Imagination: Amodal Perception as Mental Imagery. Philosophical Studies, 150(2), 239–254.

- Onof, Christian and Dennis Schulting (2015). Space as Form of Intuition and as Formal Intuition: On the Note to B160 in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Philosophical Review, 124(1), 1–58.

- Pollok, Konstantin (2017). Kant’s Theory of Normativity: Exploring the Space of Reason. Cambridge University Press.

- Segner, Johann Andreas (1773). Anfangsgründe der Arithmetik, Geometrie, und der geometrischen Berechnungen (2nd ed.). Renger.

- Sellars, Wilfrid (1968). Science and Metaphysics: Variations on Kantian Themes. Humanities Press.

- Shabel, Lisa (2003). Mathematics in Kant’s Critical Philosophy: Reflections on Mathematical Practice. Routledge.

- Stephenson, Andrew (2015). Kant on the Object-Dependence of Intuition and Hallucination. Philosophical Quarterly, 65(260), 486–508.

- Stephenson, Andrew (2017). Imagination and Inner Intuition. In Anil Gomes and Andrew Stephenson (Eds.), Kant and the Philosophy of Mind (104–123). Oxford University Press.

- Sutherland, Daniel (2004). The Role of Magnitude in Kant’s Critical Philosophy. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 34(3), 411–441.

- Tetens, Johann Nikolaus (1777). Philosophische Versuche über die menschliche Natur and ihre Entwickelung. Weidmanns Erben und Reich.

- Tolley, Clinton (2013). The Non-Conceptuality of the Content of Intuitions: A New Approach. Kantian Review, 18(1), 107–136.

- Tolley, Clinton (2016). The Difference Between Original, Metaphysical, and Geometrical Representations of Space. In Dennis Schulting (Ed.), Kantian Nonconceptualism (257–285). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tolley, Clinton (2017). Kant on the Place of Cognition in the Progression of Our Representations. Synthese, 116(3), 1–30.

- Tolley, Clinton (2019). Kant on the Role of the Imagination (and Images) in the Transition from Intuition to Experience. In Gerad Gentry and Konstantin Pollok (Eds.), The Imagination in German Idealism and Romanticism (27–47). Cambridge University Press.

- Tolley, Clinton and R. Brian Tracz (in press). Tetens on the Nature of Experience: Between Rationalism and Empiricism. In Karin de Boer and Tinca Prunea (Eds.), The Experiential Turn in Eighteenth-Century German Philosophy. Routledge.

- Treisman, Anne (1985). Preattentive Processing in Vision. Computer Vision, Graphics, and Image Processing, 31(2), 156–177.

- Watkins, Eric (2017). Kant on the Distinction between Sensibility and Understanding. In James R. O’Shea (Ed.), Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason: A Critical Guide (9–27). Cambridge University Press.

- Waxman, Wayne (1991). Kant’s Model of the Mind: A New Interpretation of Transcendental Idealism. Oxford University Press.

- Waxman, Wayne (2013). Kant’s Anatomy of the Intelligent Mind. Oxford University Press.

- Wenzel, Christian Helmut (2005). Spielen nach Kant die Kategorien schon bei der Wahrnehmung eine Rolle? Peter Rohs und John McDowell. Kant-Studien, 96(4), 407–426.

- Willaschek, Marcus and Eric Watkins (2017). Kant on Cognition and Knowledge. Synthese. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1624-4

- Williams, Jessica J. (2017). Kant on the Original Synthesis of Understanding and Sensibility. British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 56(4), 1–21.

- Wolff, Christian (1720). Vernünftige Gedanken von Gott, der Welt, und der Seele des Menschen.

Notes

References to the Critique of Pure Reason follow the convention of citing the “A” (1781) and “B” (1787) editions of that work, with the convention (A[page number]/B[page number]). All other references to Kant’s work are drawn from the Akademie Ausgabe of his works, with the convention of [volume]:[page number]. I have included an appendix with the relevant abbreviations. Though I have consulted the Cambridge edition English translations of Kant’s work, the translations here are my own.

See the extensive account of the role of images in Kant’s theory of perception by Matherne (2015); see also Tolley (2019). See Makkreel (1994: ch. 1) for an overview of different imagistic representations in Kant.

See, e.g., Allais (2015: ch. 7). Still others mention relevant passages in which Kant invokes images, yet do not indicate how these images relate to intuitions; see especially Ginsborg (2015: 67ff.).

For “intellectualist” or “conceptualist” accounts on which the imagination’s synthesis “generates intuitions” or on which intuitions depend on our “imagining space,” see Land (2016: 147–148, 157) and Longuenesse (2005: 73). See also Grüne (2016), Haag (2007), Waxman (2013), and Williams (2017: 3). For “non-intellectualist” or “non-conceptualist” accounts on which intuitions depend on the imagination, see Peter Rohs’s account in Wenzel (2005: 409) as well as Allais (2009), though Allais’s more recent account is consistent with the No Intuitions Thesis (see Allais 2017).

See, e.g., Gomes (2014: 12, 14) and Gomes (2017) for a naive realist account, and Stephenson (2015) for a representationalist account.

See especially Haag (2007), Horstmann (2018: §1), Longuenesse (1998), and Waxman (1991).

As a recent monograph puts it, “the notion of phantasm”—the Greek term for “image”— as a representation “produced by the imagination on the basis of sensible species delivered by our senses, is foreign to Kant” (Pollok 2017: 151). According to another scholar, Kant claims that “we have no image of numbers” (Axinn 2013: 98).

For instance, Wolff (1720: §235) writes in the German Metaphysics that “the representations of such things that are not present, one tends to call images [Einbildungen].” Furthermore, he claims that “images [Einbildungen] do not represent everything clearly that was contained in sensations [Empfindungen]” Wolff (1720: §235, cf. §242). See also Baumgarten (2013: §557, cf. §558).

Tetens (1777: 16) distinguishes, for instance, between “impressions” and the “traces” of impressions that are distinct from those impressions. These traces are the eventual constituents of what Tetens calls “representations” and “images.” Cf. Section 2.2.

For this reason, the imagination “belongs to sensibility” (B151, cf. A124). Compare the many other instances from various parts of the critical period: MMr (1782–1783), 29:881; MD (1792–1793), 28:672; Anth, 7:153. As Kant’s remarks, the faculty of imagination “must be distinguished from the senses as much as from the concepts” (ML2 [1790–1791?], 28:585).

See Section 2.1. Cf. Anth, 7:153, 167; MMr, 29:881; MVo, 28:449; MD, 28:673.

An even clearer indication that Kant has a progression of representations in mind comes in one of his notes in which he claims that synthesis occurs “either of apprehension as sensations or of reproduction as images [Einbildungen] or recognition as concepts” (R5636, 18:268). Longuenesse (1998: 35) also acknowledges that we should read “Einbildung” in the A-Deduction passage as involving a representational type of the power of imagination. Yet she seems to think that this image simply is an intuition.

See also Tolley (2013), Matherne (2015: 757, note 50), and Allais (2017).

In this paper, I remain agnostic about how images are “provided” to concepts, and whether images depend on concepts. For a concept-dependent account, see Matherne (2015:§6). For an account on which images do not depend on antecedent concept possession, see Ginsborg (2008)—though Ginsborg does not seem to distinguish images from intuitions.

I remain silent here on whether schemata are genetically prior to images, or whether images depend on schemata or concepts or vice-versa. Moreover, I am agnostic in this paper about whether images also depend on recognition in a concept; Matherne (2015) explicitly argues that images depend on concepts, but not on recognition in a concept.

The way Kant talks about the generation of magnitudes in image formation bears a close resemblance to how Segner (1773: 2ff.), whom Kant cites, describes the process. Cf. Kant’s reference to Segner in a note on images of number (AA, 14:55).

ML1, 28:235–236. This passage is discussed extensively by Makkreel (1994: ch. 1) and Matherne (2015).