The State of the Discipline: New Data on Women Faculty in Philosophy

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This paper presents data on the representation of women at 98 philosophy departments in the United States, which were ranked by the Philosophical Gourmet Report (PGR) in 2015 as well as all of those schools on which data from 2004 exist. The paper makes four points in providing an overview of the state of the field. First, all programs reveal a statistically significant increase in the percentage of women tenured/tenure-track faculty, since 2004. Second, out of the 98 US philosophy departments selected for evaluation by Julie Van Camp in 2004, none in 2015 has 50% women philosophy faculty overall, while one has 50% women who are tenured/tenure track. Third, as of 2015, there is a clear pyramidal shape to the discipline: Women are better represented as Assistant than Associate and as Associate than Full professors. Fourth, women philosophy faculty, especially those who are tenured/tenure track, are better represented at Non-PGR ranked programs than at PGR ranked and PGR Top-20 programs in 2015.

1. Introduction

There have been few large-scale systematic studies on the representation of women in philosophy, but existing data suggest women are less well-represented than men at all levels in philosophy (Schwitzgebel & Jennings 2017). The proportions of women in philosophy decrease as one moves from the undergraduate to faculty level, and anecdotal evidence suggests that women are often less-well represented as one ascends the professional hierarchy in both job ranks and ranks associated with program prestige (De Cruz 2018; Goddard 2008d; Haslanger 2013; Hassoun & Conklin 2015; Jennings et al. 2015; Norlock 2006; 2011; Paxton, Figdor, & Tiberius 2012; Thompson, Adleberg, Sims, & Nahmias 2016; Van Camp 2006; 2015).[1] In fact, existing data suggest philosophy has a greater gender disparity than many STEM sub-disciplines (Burrelli 2008; Hill, Corbett, & Rose 2010).

However, there are many remaining questions about the current state of the discipline, and we believe better data are essential for setting targets and evaluating performance in attempting to understand the situation for women in the field. More precisely, we need more data to identify what has happened in the academic pipeline, how philosophy departments change over time, and to understand how women are represented within professorial ranks at different kinds of departments. Limiting our discussion to an overview of philosophy departments in the United States (US), this paper starts to fill these gaps by collating existing sources of data and providing some new data on the representation of women at all faculty ranks in 2015. It presents data on the representation of women on the tenure track at 98 philosophy departments on which data from 2004 exist (courtesy of Julie Van Camp and Sally Haslanger). Moreover, it provides new data on faculty at all ranks in Philosophical Gourmet Report (PGR) ranked and unranked programs for 2015 and contextualizes these data against the gender distribution of PhDs granted in philosophy.[2] We do not focus on visiting and emeritus professors as they make up a small proportion of the total (though we provide the relevant data here: www.women-in-philosophy.org).

The paper makes the following four points. First, all programs reveal a statistically significant increase in the percent women tenured/tenure track faculty, since 2004. Second, out of the 98 US philosophy departments selected for evaluation by Julie Van Camp in 2004, none in 2015 has 50% women philosophy faculty overall, while one has 50% women who are tenured/tenure track. Third, as of 2015, there is a clear pyramidal shape to the discipline: Women are better represented as Assistant than Associate and as Associate than Full professors. Fourth, women philosophy faculty, especially those who are tenured/tenure track, are better represented at Non-PGR ranked programs than at PGR ranked and PGR Top-20 programs in 2015.[3] The data are available at this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.20574.89920.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 surveys existing data on women in philosophy. Section 3 explains our data collection methodology, presents the results, and explains how it establishes the four points above. Section 4 discusses the results.

2. Review of Existing Data on Women in Philosophy

Considerable data document the decline in the proportions of women from the undergraduate to professional level in Western academic philosophy. There is a large drop-off between women taking introductory philosophy classes and those entering the philosophy major in the US (Calhoun 2009; Paxton et al. 2012; Thompson et al. 2016). Moreover, there is a drop-off between women majoring in philosophy and those entering into graduate programs (Beebee & Saul 2011).[4]

More data on the representation of women at the faculty level will better help us to explain the decline in the proportions of women from the undergraduate to professional level in academic philosophy. Some hypothesize that small proportions of women philosophy faculty play a role in philosophy’s inability to recruit new women into the major, meaning the likely cause of the decline in the proportions of women from the undergraduate to professional level stems, at least in part, from the low proportions of women at the professional level.[5] For example, Paxton et al. (2012) reports a positive correlation between the presence of women faculty and the recruitment of women philosophy majors (though the women faculty are not necessarily the instructors of record in the courses examined). Thus, we need more data on gender disparities at the faculty level. This paper focuses on faculty representation in the US.

As noted above, it appears that the greatest drop in women occurs between introductory philosophy classes and declaring the philosophy major, but there is a continuous decline in the proportions of women in the US as one ascends the levels of the hierarchy (Paxton et al. 2012). Paxton et al. (2012) reports gender parity at the level of introductory philosophy classes. According to the National Science Foundation National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics Digest of Education Statistics [NCSES], women philosophers receive around 30% of earned bachelor’s degrees (NCSES 2015). Since the NCSES (2015) began collecting data in 1949, women have consistently received fewer than 30% of total Philosophy PhDs (see also Van Camp 2015). However, Schwitzgebel and Jennings (2017) note that the percent of women philosophy PhDs in the US increased significantly, from 17% to 27%, between the 1970s and 1990s. The increase in the percent of women philosophy PhDs has since slowed, with women earning below 28% of philosophy PhDs, on average, between 1990 and 2014 (see also Schwitzgebel 2016). Haslanger (2013) shows that women in the US receive roughly 30% fewer PhDs in philosophy than women in other humanities disciplines where women earn nearly 60% of PhDs, and philosophy is comparable to mathematics with only women in physics receiving fewer PhDs. Haslanger’s data is consistent with the most recent Survey of Earned Doctorates, which shows that women receive 29.2% of PhDs in Philosophy as of 2015 (NCSES 2015).

There is also a decrease between the percentage of women earning a PhD in US philosophy departments and those hired at academic programs, though women are as likely to continue into academic positions as their male counterparts after receiving PhDs.[6] Jennings et al. (2015) reported that, in the US, women accounted for 28% of academic job hires between 2012 and 2014, meaning, in recent years, women are hired in a higher proportion than their presence in the applicant pool. Solomon and Clark (2009) noted that women are hired at roughly the same proportion across each job type (e.g., full time and part time positions).

There is possible attrition at the faculty level in the US. Norlock (2006; 2011) reports that women in the US comprise nearly 17% of full-time faculty. Norlock’s (2006; 2011) and Jennings et al.’s (2015) findings, taken together, are consistent with the hypothesis that more women have recently been hired onto the tenure track as Assistant Professors, but that these tenure track women have not yet had the opportunity to receive tenure and promotions because they were hired relatively recently. Nonetheless, current research suggests that women are less likely than men to be tenured and promoted at US institutions where similar trends are reported (Chen, Kim, and Liu 2016; Curtis 2011; Finkelstein, Conley, and Schuster 2016; Junn 2012; Institute of Education Statistics, National Center for Education Statistics, IPEDS Data Center [NCES] 2016).[7]

Further data are needed to identify changes in philosophy departments over time and to understand how women are represented in different professorial types and ranks at different kinds of departments (e.g., PGR ranked and unranked programs).[8] Subsequent sections presents some such data.

3. New Data on Women in Philosophy

Methods

This study focuses on the number of women and men at 98 philosophy departments in the US. We present new data on the number of women and men at 50 programs ranked by the Philosophical Gourmet Report (PGR) in 2015 as well as 48 programs not ranked by the PGR in 2015 (Leiter 2016). We selected these programs based on the availability of the only existing historical data compiled by Julie Van Camp between 2004 and 2015 and Sally Haslanger in 2009.[9]

Although the PGR has produced rankings for philosophy departments since 1989, both its methods and results are controversial.[10] Criticisms of the PGR methodology include: (1) selection bias in the sampling methods; (2) the use of experts in one area of specialization to rank entire programs in that area of specialization; (3) its non-representative sample of evaluators (both in terms of area of specialization and demographics); and (4) its analytic focus (Bruya 2015). We would add that even if we suppose the evaluators are well-placed to judge faculty performance, they do not even receive the CVs of the faculty they are evaluating.

So, while we do not intend to endorse the PGR’s methodology or rankings by examining philosophy programs ranked by the PGR, we engage with the PGR for two reasons. First, these are the programs for which Julie Van Camp began collecting data on the proportions of philosophy faculty by gender in 2004, making them the only programs for which we can conduct a longitudinal study. We compare our new data against the historical data to get a sense of changes in the number of women and men over the last 11 years. Van Camp (2015) reports only data on tenured/tenure-track faculty in the US and does not include data on adjuncts/lecturers or the breakdown on the tenure-track by rank. So, we present new data on the number and proportion of women and men, at each faculty rank, for schools with historical data.

Second, we hypothesize that the most prestigious philosophy programs have the lowest proportions of women faculty in the discipline over time. We make this hypothesis, in part, on the basis of anecdotal evidence from testimonials, such as those found on the “What is it like to be a woman in philosophy?” blog, suggesting that women are often less-well represented as one ascends the professional hierarchy in both job ranks and ranks associated with program prestige.[11] But also, we find evidence of prestige bias in other areas of philosophy, including in the most highly ranked philosophy journals (Leiter 2015; Wilhelm et al. 2017). To test this hypothesis, we require access to historical data including measures of philosophy program prestige rank. Only the PGR has produced any such philosophy-specific rankings.[12]

Taking gender into account, we compare programs using four categories: PGR Top-20, PGR ranked (sometimes only referred to as ranked and includes PGR Top-20 programs), Non-PGR ranked (sometimes only referred to as unranked), and All Programs (ranked and unranked together). We distinguish between PGR Top-20 and PGR programs for two reasons. First, while Van Camp (2004; 2015) noted no clear pattern in the proportions of women distributed across the PGR ranking in earlier reports, she also reports that PGR Top-20 programs have the greatest number of philosophy faculty. So, despite apparent parity in the proportions of women philosophy faculty, the underlying differences in the numbers could be statistically different and this requires investigation. Second, existing research on the representation of women philosophy faculty in the US examines programs typically falling in the PGR Top-20. We therefore compare between PGR Top-20 programs and PGR ranked programs in order to learn more about the relationship between program ranks and the proportion of women philosophy faculty present (Haslanger 2008).

Data was collected on the number of men and women faculty at all ranks for all of the programs included in Van Camp’s 2015 data. Our methodology is largely in agreement with the methodology of the other rankings from past years by Sally Haslanger and Julie Van Camp. Our data were collected from individual department websites.[13] While we acknowledge the presence of transgender, queer, and non-traditional gendered philosophers within the field of philosophy, we follow Van Camp by using pronouns and other common indicators of gender to classify individuals by gender based on the name being either traditionally male or female. For gender ambiguous names, we utilized the self-reported gender of the philosopher or the gender of the pronouns used to describe the person. When necessary, we relied on information provided by individual departments.

Here are some of the inclusion/exclusion criteria that we used. We did not count affiliated professors as philosophy professors, although we did count joint professors as professors, for example, Professor of Philosophy and Psychology would count, but a Professor of Psychology affiliated with the Philosophy department would not count. We primarily considered whether they were listed as departmental faculty or departmental affiliates. This is in agreement with Van Camp’s data on the premise that joint faculty members usually have full decision-making power within the department and serve as most other faculty do despite their teaching in other departments. The same logic applied to a philosophy professor also listed as a high-level administrator like a Dean; we counted them along with the faculty. Likewise, the reason for separating out lecturers and adjuncts from tenure track professors was their exclusion from department governance in the US.[14] We refer to all Assistant, Associate and Full Professors as “tenured/tenure track.”[15] We refer to non-tenure track positions as lecturer/adjunct, and we refer to tenured/tenure track together with lecturer/adjunct positions as All positions. We did not count post-docs and graduate assistants.[16] Nor did we count visiting scholars. If there was a faculty member listed as head of some research organization, or if the title did not clearly fit into one of our categories, we individually confirmed their title. We did not count retired faculty or emeritus faculty.[17]

Our statistical methods were as follows. The proportions of women in each type of academic position were calculated using the number of women divided by total number of positions of the appropriate type. First, we examined distributions of the proportion of tenured/tenure track women faculty at ranked and unranked programs using the nonparametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. To analyze the difference in the types of programs and the effect of different types of academic positions in the 2015 data, we conducted Poisson regressions with robust variance estimation.[18] As the outcome, we took the number of women in each type of academic position, tenure track and non-tenure track; the logarithm of total number of positions of each type was used as an offset variable to estimate the proportions.[19] Using data for six time points between 2004 and 2015, we employed the same Poisson regressions with robust variance estimation to conduct a longitudinal analysis examining changes in the number of women and the number of men in tenured/tenure track positions at ranked vs. unranked and PGR Top-20 vs. ranked institutions over time.

Because it is more difficult to determine other demographic data from faculty profiles, data was not collected on the representation of other minorities in philosophy. Ideally, we would include data from all departments with graduate programs in philosophy. The remainder of this paper suggests, however, that even this limited dataset can teach us a lot about the state of the discipline. The data are publicly available at www.women-in-philosophy.org".

Results

In what follows, we present the results of our analysis as evidence for each of our four points. Consider each of our results in turn:

1. Since 2004, all program types reveal a highly statistically significant increase in the percent women tenured/tenure track faculty.

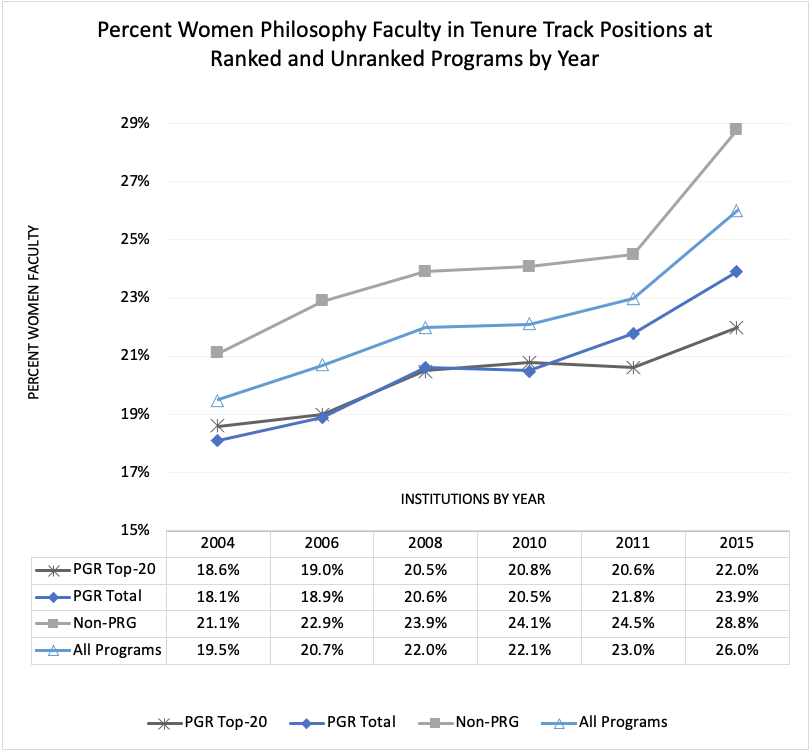

Consider Figure 1, depicting the upward trends observed in the proportions of women philosophy faculty in all tenured/tenure track positions by program type.[20]

We hypothesized that the increased proportions of women philosophy faculty is due to an increase in the number of women and not due to a decrease in the number of men, since our results are consistent with a decline in the number of men (and no change in the number of women) in philosophy departments between 2004 and 2015.[21] We find that the statistically significant increase in the proportion of women is not primarily due to a decrease in the total number of men faculty in philosophy departments. There was no statistically significant change in the number of men over time at PGR Top-20 and PGR ranked programs, but there was a statistically significant decrease in the number of men at unranked programs (p=0.0005)***.[22] The number of women in all programs, ranked and unranked, increased significantly over time (p<0.0001)***.

2. Out of the 98 US philosophy departments selected for evaluation by Julie Van Camp in 2004, we find that none in 2015 has 50% women philosophy faculty overall, while one has 50% women who are tenured/tenure track.

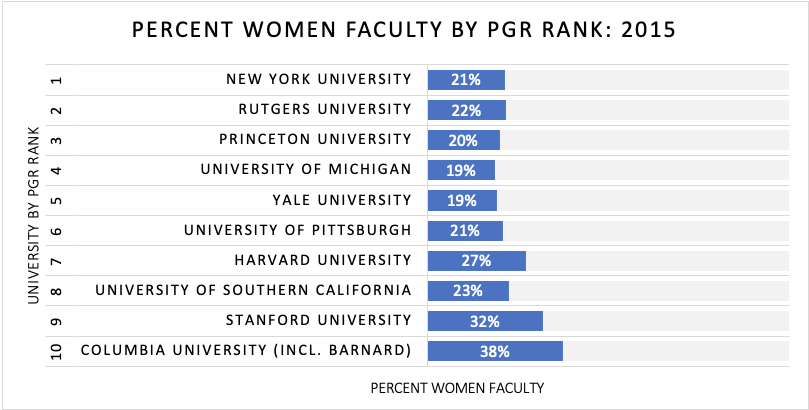

See these results in the following figures. Figure 2 depicts the Top-10 and Bottom-10 programs ranked by the proportions of women philosophy faculty present in all positions for 2015.

Figure 3 depicts the Top-10 and Bottom-10 programs ranked by the proportions of women philosophy faculty present in tenured/tenure track positions in 2015.

3. As of 2015, there is a clear pyramidal shape to the discipline: Women are better represented as Assistant than Associate and as Associate than Full professors.

Consider Image 1, depicting the proportions of Full, Associate, and Assistant Professors across All Programs. Women comprise nearly 20% of all Full Professors, 30% of all Associate Professors, and 40% of Assistant Professors in philosophy. Correspondingly, men comprise roughly 80% of all Full Professors, 70% of all Associate Professors, and 60% of Assistant Professors in philosophy. We found similar patterns for PGR Top-20, PGR ranked, and Non-PGR ranked programs.

For All and Non-PGR ranked programs, the differences in the proportions of women in each tenured/tenure track job type are statistically significant (to different degrees).[23] For PGR Top-20 and PGR ranked programs the differences in the proportions of women in each tenured/tenure track job type are statistically significant, excepting the differences between Assistant and Associate professors for both program types.

4. Women philosophy faculty, especially those who are tenured/tenure track, are better represented at Non-PGR ranked programs than at PGR ranked and PGR Top-20 programs in 2015.

Consider Figure 4, depicting the proportions of women philosophy faculty for all faculty ranks and all programs types in 2015. On average, PGR Top-20 and PGR ranked programs have around 22% and 24% women philosophy faculty respectively, while unranked programs have 27%.[24] There is no statistically significant difference in the proportion of women between unranked and PGR ranked programs, but the difference is weakly statistically significant between unranked and PGR Top-20 programs.[25] Moreover, the difference between the proportions of women philosophy faculty who are tenured/tenure track at unranked programs compared to ranked and PGR Top-20 programs respectively is moderately statistically significant.[26]

4. Discussion

This paper represents the first longitudinal study of philosophy faculty by gender in the US. Unlike previous studies, which examine the proportions of women philosophy faculty at particular time points, we analyzed changes in the numbers and proportions of faculty by gender at 98 philosophy programs between 2004 and 2015. Our data show a statistically significant increase in the proportions of women philosophy faculty in the US over an eleven-year span. In general, this is consistent with the trends we see for women in US universities overall (Parker 2015).

This paper also represents the only existing evidence that the most highly ranked programs, according to the PGR, consistently employ lower proportions of women (especially on the tenure track) than unranked programs in the US over time. Unlike ranked programs, we find that one unranked program has reached 50% tenured/tenure track women, although none have reached 50% women philosophy faculty overall. Our findings on so-called prestige effects contrasts with Schwitzgebel and Jennings (2017) who reported no prestige effect at different program ranks.[27] One possible explanation for this is that Schwitzgebel and Jennings (2017) used an approximation approach to detect differences (a z-test). While this approach may have been appropriate for their study, this approach is not appropriate for the dataset examined in this study. This test assumes that (1) the data are normally distributed and that (2) the number of available positions in each program does not matter (they compared proportions only). While the first assumption could hold with a large enough sample size, this would diminish the power of the test considerably. The second assumption, ignoring the department size at each program, disregards substantial information from the dataset we have available and lowers the power needed to detect the significance of the observed difference even more. We used a method more appropriate for our data—Poisson regression. This method is widely accepted as a standard for the analysis of count data which we have on hand, the number of men and women at each program to the number of total positions in that program.

Finally, this paper represents the only existing study comparing the proportions of women philosophy faculty at different faculty ranks across differently ranked programs. Across each program type, there is a clear pyramidal shape to the discipline with more women faculty at lower ranks and lower ranked programs.

There are two hypotheses that may explain several of our results (e.g., the fact that proportions of women faculty remain are especially low at higher ranks—Associate and Full Professor). The first is that women are hired for tenure track positions but not tenured and promoted. Recent research on tenure and promotion in US institutions where similar trends are reported suggests this hypothesis (Chen, Kim, and Liu 2016; Curtis 2011; Finkelstein, Conley, & Schuster 2016; Junn 2012; NCES 2016).[28] The second is that philosophy as a discipline in the US is hiring more women onto the tenure track as Assistant Professors because the size of the applicant pool is increasing due to an increase in PhDs earned by women (NCSES 2015). However, these tenure track women have not yet had the opportunity to receive tenure and promotion because they were hired relatively recently. For instance, if women philosophy faculty were hired in proportion to a historically small applicant pool, that could explain the pyramidal shape of the discipline. As of 2015, the proportion of Assistant Professors is comparable to the size of the likely applicant pool in the same year.[29] Perhaps the low proportion of women who are currently Associate and Full Professors of philosophy reflects the even smaller size of the applicant pool further in the past. Contextualizing our results against the gender distribution of PhDs granted in philosophy yields some insight into the question.

On our best estimate, the proportion of women who are currently Full Professors of philosophy does not reflect the size of the applicant pool further in the past. According to the NCSES (1994-2015), the proportion of women earning PhDs in philosophy has oscillated around 27% since 1994 (and we expect the average Full Professor in 2015 received her PhD in the 1990’s). Yet, women account for 20% of Full Professors. This might suggest women are not hired and tenured in proportion to their presence in the historical applicant pool. However, it does not rule out the size of the applicant pool and wait times between hiring and tenuring as contributing factors.

In addition, the observed proportions of women tenured/tenure track faculty at PGR ranked and Top-20 programs is not explained by historically small proportions of women earning PhDs in philosophy and applying for jobs. The most highly ranked philosophy programs, according to the PGR, are also the programs with the greatest number of total faculty overall, and, presumably, they are most well-funded. This means that PGR ranked programs have historically had the most resources for hiring and tenuring women, and, possibly, the most opportunities for hiring women due to their attractiveness as the most prestigious faculties in philosophy.

Wherever the best explanation for our findings lies, there is also a normative question about what the appropriate percentage (and percent increase) in women should be in the discipline (if any). That is, further philosophical argument is necessary to draw any ethical conclusions from our data. There is the question of the standard to which departments should be held. Should programs do more to ensure a faculty representative of the general population, where women are approximately 50% of the population? This proposal is increasingly realistic as unranked programs achieve the 50% benchmark. Should philosophy programs at least ensure representation relative to the applicant pool now (or historically)? Once again, we do see this for unranked programs but not the most highly ranked PGR programs (See Appendix II).

One reason to say that the programs we evaluated should do more (assuming we should have more women philosophers) is that PhD granting departments and universities have significant impacts on the size of the potential application pool and the demographics of its representativeness. They are the ones providing the stream of candidates, and they can take steps to ensure that the pool is representative. Departments also judge what qualifications count and hence help determine the size of the pool of qualified candidates in deciding on admissions to graduate programs. Even if one cannot expect the applicant pool to be 50% women in the next few years, one might argue that departments should do more to promote equality than just pull a proportionally equal number of men and women from the applicant pool. It might technically be possible for departments and universities to increase the proportions of women admitted into philosophy programs within 10 years so that women are equally represented in the potential applicant pool (the time necessary to get a BA and PhD in philosophy). Even if a realistic time period for increasing representation to parity were more on the order of 40 years, universities and departments can take additional steps to do so. Since no single department or university can increase the overall proportion of women in philosophy on its own, perhaps we can assess each according to its relative contribution. In any case, one can easily test for bias against many alternative (potentially justifiable) expectations (not just relative to the proportion of women in the applicant pool or the population at large).

Even if the bar is representation relative to the applicant pool, perhaps it is worth noting that there is some basis for holding departments responsible for discrimination using statistics in the law. In Ward’s Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio (1989), the “[c]ourt held that a case of disparate impact could generally be established only by comparing minority representation in the jobs at issue with minority representation in the labor force with the skills for such jobs” (see also Scanlan 2004: para. 4).[30] Obviously, the arguments suggested here would require further development before deployment in legal contexts. Still, if the proportions of women philosophy faculty do not increase, perhaps the data can help.

Further research is also pressing and important for many other reasons. Additional data would, for instance, allow us to consider different causal explanations for apparent bias where it exists. At this point, we can only give a partially empirical, partially theoretical, argument for the conclusion that the glass-ceiling phenomenon contributes to the fact that 25% of the faculty are women in philosophy. For example, we argued that the discrepancy between the proportions of tenure track women Assistant Professors and tenured Associate and Full Professors cannot be fully explained by a smaller pool of women applicants historically. This indicates that part of the problem may be the existence of a glass ceiling, and women may be falling out of the discipline because they are not receiving tenure.[31] To investigate changes in tenure and promotion of women, we need further data on the distribution of women at all ranks in the profession for at least the next 5–10 years.

Further data are necessary to answer some other questions as well. Schwitzgebel and Jennings (2017) provide some data on AOS that suggests that women are most well-represented in value theory. But we do not have data on areas of specialization at different kinds of programs for 2015. So we cannot consider whether women are less well represented at PGR ranked programs because those programs hire fewer people in value theory or for some other reason.

Nevertheless, the data we have collected should be useful for many purposes. It provides us with an overview of the distribution of women faculty in philosophy and is now publicly available in an easily digestible form at www.women-in-philosophy.org. Potential faculty and graduate students may consider the number of women in the departments in making decisions about where to apply and which offers to accept. Faculty may use it in making arguments for admissions and hiring decisions and in evaluating peer institutions. University administrators can use the data to hold departments to account.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we provided an overview of the state of women faculty in philosophy. While we found that none of the 98 departments selected for evaluation by Julie Van Camp in 2004 has an overall average of 50% women philosophy faculty in 2015, all kinds of programs have shown a statistically significant increase in the percent women tenured/tenure track faculty. Yet, as of 2015, there is a clear pyramidal shape to the discipline: Women are better represented as Assistant than Associate and Associate than Full professors. Finally, women (especially tenured/tenure track women) are also better represented at Non-PGR ranked programs than at PGR ranked programs. There is room for significant philosophical disagreement about the relevance of these findings. However, those who think the existing proportions of women in philosophy is unacceptable for any reason need more information to understand why women are underrepresented as faculty, how philosophy departments change over time, and what to do about it. We hope this paper encourages more people to use the database we have created to support this inquiry and increase the proportions of women in philosophy.

Appendix I

In Appendix I, we show the Top-10 and Bottom-10 programs ordered by percent women faculty (in all position types), which were most highly recommended in one or more categories for graduate work in The Pluralist Guide to Philosophy (TPGP) and for which we have 2015 faculty data. The TPGP recommends programs with strengths in each of these different groups: American Philosophy Continental Philosophy, Critical Philosophy and Race/Ethnicity, Feminist Philosophy, Departmental Climate, GLBT Philosophy, and Latin American and Latino/a Issues in Philosophy. We created a list of programs that received the highest recommendation level for each group (or if none was highly recommended for a given category, we included recommended programs in our list). We then ranked all the programs in the list on which we had data by proportion of women faculty (overall). Note that the ranking here does not reflect TPGP rank but the proportion of women in programs that were highly recommended (or if none was highly recommended, recommended) by the TPGP in at least one category.

Appendix II

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to support provided by the Demographics in Philosophy Project advisory board, with special thanks to Julie Van Camp, Sally Haslanger, Ruth Chang, Tom Dougherty, Edouard Machery, and Eric Schwitzgebel for providing feedback on early drafts. Thanks also to Jennifer Dunn, Aaron Schultz, and Morgan Thompson for helping to collect the data, as well as to Mei-Hsiu Chen and Junyi Dong for statistical consulting on early drafts. Finally, we thank Jevin West, Michael Nekrasov, Lucio Esposito, Shen-yi Liao, and the many graduate and undergraduate students who have assisted with this project over the years (see www.women-in-philosophy.com for their details), anonymous referees, as well as the editors of Ergo, for comments on later drafts.

References

- Aboulafia, Mitchell (2018, January 1). The Philosophical Gourmet Report. A User’s Guide to Philosophy without Rankings. Retrieved from http://www.philosophyrankings.com

- Allen-Hermanson, Sean (2017). Leaky Pipeline Myths: In Search of Gender Effects on the Job Market and Early Career Publishing in Philosophy. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00953

- American Philosophical Association (2015a). The APA Guide to Graduate Programs in Philosophy. Retrieved from http://www.apaonline.org/page/gradguide

- American Philosophical Association (2015b). Membership Demographic Statistics, FY2014, FY2015. Retrieved from http://www.apaonline.org/page/demographics

- Antony, Louise (2012). Different Voices or Perfect Storm: Why Are There So Few Women in Philosophy? Journal of Social Philosophy, 43(3), 227–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2012.01567.x

- Baron, Sam, Tom Dougherty, and Kristie Miller (2015). Why Is There Female Under-Representation among Philosophy Majors? Evidence of a Pre-University Effect. Ergo, 2(14), 329–365. http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/ergo.12405314.0002.014

- Beebee, Helen and Jenny Saul (2011). Women in Philosophy in the UK, A Report by the British Philosophical Association and the Society for Women in Philosophy UK. Retrieved from http://www.bpa.ac.uk

- Benétreau-Dupin, Yann and Guillaume Beaulac (2015). Fair Numbers: What Data Can and Cannot Tell Us About the Underrepresentation of Women in Philosophy. Ergo, 2(3), 59–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/ergo.12405314.0002.003

- Botts, Tina Fernandes, Liam Kofi Bright, Myisha Cherry, Guntur Mallarangeng, and Quayshawn Spencer (2014). What Is the State of Blacks in Philosophy? Critical Philosophy of Race, 2(2), 224–242. https://doi.org/10.5325/critphilrace.2.2.0224

- Bowell, Tracy (2015). The Problem(s) of Women in Philosophy: Reflections on the Practice of Feminism in Philosophy from Contemporary Aotearoa/New Zealand. Women’s Studies Journal, 29(2), 4–21.

- Bruya, Brian (2015). Appearance and Reality in the Philosophical Gourmet Report: Why the Discrepancy Matters to the Profession of Philosophy. Metaphilosophy, 46(4–5), 657–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/meta.12161

- Buckwalter, Wesley and Stephen Stich (2014). Gender and Philosophical Intuition. In Joshua Knobe and Shaun Nichols (Eds.), Experimental Philosophy: Volume 2 (307–346). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199927418.003.0013

- Burrelli, Joan (2008). Thirty-Three Years of Women in S&E Faculty Positions. National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.nsf.gov

- Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977).

- Calhoun, Cheshire (2009). The Undergraduate Pipeline Problem. Hypatia, 24(2), 216–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2009.01040.x

- Calhoun, Cheshire (2015). Precluded Interests. Hypatia, 30(2), https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12149

- Chen, Jihui, Myongjin Kim, and Qihong Liu (2016). Do Female Professors Survive the 19th-Century Tenure System?: Evidence from the Economics Ph.D. Class of 2008. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2885951

- Coxe, Stefany, Stephen West, and Leona Aiken (2009). The Analysis of Count Data: A Gentle Introduction to Poisson Regression and its Alternatives. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634175

- Curtis, John (2011). Persistent Inequity: Gender and Academic Employment. American Association of University Professors. Retrieved from https://www.aaup.org/NR/rdonlyres/08E023AB-E6D8-4DBD-99A0-24E5EB73A760/0/persistent_inequity.pdf

- De Cruz, Helen (2018). Prestige Bias: An Obstacle to a Just Academic Philosophy. Ergo, 5(10), 259–287. http://doi.org/10.3998/ergo.12405314.0005.010

- Dodds, Susan and Eliza Goddard (2013). Not Just a Pipeline Problem: Improving Women’s Participation in Philosophy in Australia. In Katrina Hutchison and Fiona Jenkins (Eds.), Women in Philosophy: What Needs to Change? (143–163). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199325603.003.0008

- Dotson, Kristie (2011). Concrete Flowers: Contemplating the Profession of Philosophy. Hypatia, 26(2), 403–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2011.01176.x

- Dougherty, Tom, Sam Baron, and Kristie Miller, K. (2015). Female Under-Representation among Philosophy Majors: A Map of the Hypotheses and a Survey of the Evidence. Feminist Philosophical Quarterly, 1(1), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.5206/fpq/2015.1.4

- Finkelstein, Martin J., Valerie M. Conley, and Jack H. Schuster (2016, April). Taking the Measure of Faculty Diversity. TIAA Institute. Retrieved from https://www.tiaainstitute.org/publication/taking-measure-faculty-diversity

- Frodeman, Robert and Jennifer Rowland (2009). De-Disciplining the Humanities. Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, 29, 62–72.

- Goddard, Eliza (2008a). Improving the Participation of Women in the Philosophy Profession; Executive Summary. Australasian Association of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://aap.org.au/Resources/Documents/publications/IPWPP/IPWPP_ExecutiveSummary.pdf

- Goddard, Eliza (2008b). Improving the Participation of Women in the Philosophy Profession; Report A: Staffing by Gender in Philosophy Programs in Australian Universities. Australasian Association of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://aap.org.au/Resources/Documents/publications/IPWPP/IPWPP_ReportA_Staff.pdf

- Goddard, Eliza (2008c). Improving the Participation of Women in the Philosophy Profession; Report B: Appointments by Gender in Philosophy Programs in Australian Universities. Australasian Association of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://aap.org.au/Resources/Documents/publications/IPWPP/IPWPP_ReportB_Appointments.pdf

- Goddard, Eliza (2008d). Improving the Participation of Women in the Philosophy Profession; Report C: Students by Gender in Philosophy Programs in Australian Universities. Australasian Association of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://aap.org.au/Resources/Documents/publications/IPWPP/IPWPP_ReportC_Students.pdf

- Hall, Pamela C. (1993). From Justified Discrimination to Responsive Hiring: The Role Model Argument and Female Equity Hiring in Philosophy. Journal of Social Philosophy, 24(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.1993.tb00494.x

- Haslanger, Sally (2008). Changing the Ideology and Culture of Philosophy: Not by Reason (Alone). Hypatia, 23(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2008.tb01195.x

- Haslanger, Sally (2013). “Survey of Earned Doctorates % Women.” APA Committee on the Status of Women. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/qnejc6z

- Hassoun, Nicole and Sherri Conklin (2015). Data on Women in Philosophy. Retrieved from http://women-in-philosophy.org

- Heck, Richard (2016, August 5). About the Philosophical Gourmet Report. Retrieved from http://rkheck.frege.org/philosophy/aboutpgr.php

- Healy, Kieran. (2013, June 19). Lewis and the Women [blog post]. Retrieved from https://kieranhealy.org/blog/archives/2013/06/19/lewis-and-the-women/

- Healy, Kieran (2015, February 25). Gender and Citation in Four General-Interest Philosophy Journals, 1993-2013 [blog post]. Retrieved from https://kieranhealy.org/blog/archives/2015/02/25/gender-and-citation-in-four-general-interest-philosophy-journals-1993-2013/

- Hill, Catherine, Christianne Corbett, and Andresse St. Rose (2010). Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. AAUW. Retrieved from https://www.aauw.org/research/why-so-few/

- Institute of Education Statistics, National Center for Education Statistics, IPEDS Data Center (2016). Full-Time Instructional Staff, by Faculty and Tenure Status, Academic Rank, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender (Degree-Granting Institutions): 2015 Fall 2015 Staff Survey. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/use-the-data

- Irvin, Sherri (2014, December 10). Diversity in Aesthetics Publishing [blog post]. Retrieved from https://aestheticsforbirds.com/2014/12/10/diversity-in-aesthetics-publishing-by-sherri-irvin/

- Jennings, Carolyn Dicey (2014a, June 12). Job Placement 2011-2014: Overview on Gender [blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.newappsblog.com/2014/06/job-placements-2011-2014-first-report.html

- Jennings, Carolyn Dicey (2014b, June 18). Job Placement 2011-2014: Overview on AOS [blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.newappsblog.com/2014/06/job-placement-2011-2014-overview-on-aos.html

- Jennings, Carolyn Dicey (2015a, March). An Empirical Look at Gender and Research Specialization. Invited colloquium presentation for the Metaphilosophy & Diversity Colloquium, Boston University.

- Jennings, Carolyn Dicey (2015b, October 19). Tracking the Job Market: A Start [blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.newappsblog.com/2015/10/tracking-the-job-market-a-start.html

- Jennings, Carolyn Dicey (2016, January 17). Women and Minorities in Philosophy: Which Programs Do Best? [blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.newappsblog.com/2016/01/women-and-minorities-in-philosophy-which-programs-do-best.html

- Jennings, Carolyn Dicey, Angelo Kyrilov, Patrice Cobb, Justin Vlasits, David W. Vinson, Evette Montes, and Cruz Franco (2015). Academic Placement Data and Analysis: 2015 Final Report. American Philosophical Association. Retrieved from https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.apaonline.org/resource/resmgr/grantreports/2014APDAreport.pdf

- Junn, Jane. (2012). Analysis of Data on Tenure at USC Dornsife. Memo to USC Dornsife Faculty Council. University of Southern California. Retrieved from https://feministphilosophers.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/c9093-junnreport.pdf

- Krishnamurthy, Meena (2017). The Underrepresentation of Women in Elite Ethics Journals: To Quota or Not to Quota? Public Affairs Quarterly, 31(2), 107–124.

- Krishnamurthy, Meena, Shen-yi Liao, Monique Deveaux, and Maggie Dalecki (2017). The Underrepresentation of Women in Prestigious Ethics Journals. Hypatia, 32(4), 928–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12351

- Leiter, Brian (2012, February 1). The Five Most Common Objections to the PGR [blog post]. Retrieved from https://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2012/02/the-five-most-common-objections-to-the-pgr.html

- Leiter, Brian (2015, December 14). Brian Bruya's Alleged Critique of the PGR [blog post]. Retrieved from https://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2015/12/brian-bruya-pgr.html

- Leiter, Brian (2016, September 13). 2016-17 Ranking of the Best Philosophy PhD Programs Taking Account of Faculty Changes Since the Fall 2014 PGR [blog post]. Retrieved from https://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2016/10/fall-2014-pgr-seen-from-2016-17-taking-account-of-faculty-changes.html

- Leslie, Sarah-Jane, Andrei Cimpian, Meredith Meyer, and Edward Freeland (2015). Expectations of Brilliance Underlie Gender Distributions across Academic Disciplines. Science, 347(6219), 262–265. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261375

- McAffee, Noëlle (2007, November 24). Philosophy Rankings [blog post]. Retrieved from https://gonepublic.net/2007/11/24/philosophy-rankings/

- McAffee, Noëlle (2010a, October 21). Ranking Continental Philosophy Programs [blog post]. Retrieved from https://gonepublic.net/2010/10/21/ranking-continental-philosophy-programs/

- McAffee, Noëlle (2010b, November 8). Shadow of a Phantom or How to Do a Survey. Retrieved from https://gonepublic.net/2010/11/08/the-shadow-of-a-phantom-or-how-to-do-a-survey/

- McAffee, Noëlle (2011, November 15). The Favorites’ Favorites: Another Round of PGR Rankings of Continental Philosophy [blog post]. Retrieved from https://gonepublic.net/2011/11/15/the-favorites-favorites-another-round-of-pgr-rankings-of-continental-philosophy/

- McAffee, Noëlle (2014, February 12). Is the PGR Sexist? [blog post]. Retrieved from https://gonepublic.net/2014/02/12/is-the-pgr-sexist/

- Morganson, Valerie J., Meghan P. Jones, and Debra A. Major (2010). Understanding Women's Underrepresentation in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics: The Role of Social Coping. Career Development Quarterly, 59(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2010.tb00060.x

- Moulton, Janice (1989). A Paradigm of Philosophy: The Adversary Method. In Ann Garry and Marilyn Pearsall (Eds.), Women, Knowledge, and Reality: Explorations in Feminist Philosophy (5–20). Routledge.

- National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (2015). Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities (1994-2015). Special Report. Retrieved from https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/doctorates/

- Norlock, Kathryn (2006). Women in the Profession: A Report to the CSW. APA Committee on the Status of Women. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/sfs3pvk

- Norlock, Kathryn (2011). Update. APA Committee on the Status of Women. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/rj8w2p5

- O’Neill, G. Patrick and Paul N. Sachis (1994). The Importance of Refereed Publications in Tenure and Promotion Decisions: A Canadian Study. Higher Education, 28(4), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01383935

- Parker, Patsy (2015). The Historical Role of Women in Higher Education. Administrative Issues Journal: Connecting Education, Practice, and Research, 5(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.5929/2015.5.1.1

- Paxton, Molly, Carrie Figdor, and Valerie Tiberius (2012). Quantifying the Gender Gap: An Empirical Study of the Under-Representation of Women in Philosophy. Hypatia, 27(4), 949–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01306.x

- QS World University Rankings (2019). University Rankings: 2019. Retrieved from https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2019

- Rask, Kevin N. and Elizabeth M. Bailey (2002). Are Faculty Role Models? Evidence from Major Choice in an Undergraduate Institution. The Journal of Economic Education, 33(2), 99–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220480209596461

- Rini, Adriane (2013). Models and Values: Why Did New Zealand Philosophy Departments Stop Hiring Women Philosophers? In Katrina Hutchison and Fiona Jenkins (Eds.) Women in Philosophy: What Needs to Change? (127–142). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199325603.003.0007

- Rooney, Phyllis (2010). Philosophy, Adversarial Argumentation, and Embattled Reason. Informal Logic, 30(3), 203–234. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v30i3.3032

- Saul, Jennifer (2012). Ranking Exercises in Philosophy and Implicit Bias. Journal of Social Philosophy, 43(3), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2012.01564.x

- Saul, Jennifer (2013). Implicit Bias, Stereotype Threat, and Women in Philosophy. In Katrina Hutchison and Fiona Jenkins (Eds.), Women in Philosophy: What Needs to Change? (39–60). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199325603.003.0003

- Saul, Jennifer (2017). Why So Few Women in Value Journals? How Could We Find Out? Public Affairs Quarterly, 31(2), 125–142.

- Scanlan, James P. (2004). Statistical Proof of Discrimination. Reprinted from Affirmative Action, An Encyclopedia (838–840), James A. Beckman (Ed.), 2004, Greenwood Press. Retrieved from http://jpscanlan.com/images/Statistical_Proof_of_Discrimination.pdf

- Schouten, Gina (2015). The Stereotype Threat Hypothesis: An Assessment from the Philosopher’s Armchair, for the Philosopher’s Classroom. Hypatia, 30(2), 450–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12148

- Schwitzgebel, Eric (2015a, March 31). Percentages of Women on the Program of the Pacific APA [blog post]. Retrieved from http://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2015/03/proportions-of-women-on-program-of.html

- Schwitzgebel, Eric (2015b, November 17). Percentage of Women at APA Meetings, 1955, 1975, 1995, 2015 [blog post]. Retrieved from http://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2015/11/percentage-of-women-at-apa-meetings.html

- Schwitzgebel, Eric (2015c, December 15). Only 13% of Authors in Five Leading Philosophy Journals Are Women [blog post]. Retrieved from http://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2015/12/only-13-of-authors-in-five-leading.html

- Schwitzgebel, Eric (2016, January 13). Percentages of U.S. Doctorates in Philosophy Given to Women and to Minorities, 1973-2014 (guest post by Eric Schwitzgebel) [blog post]. Retrieved from http://dailynous.com/2016/01/13/percentages-of-u-s-doctorates-in-philosophy-given-to-women-and-to-minorities-1973-2014-guest-post-by-eric-schwitzgebel/

- Schwitzgebel, Eric and Carolyn Dicey Jennings (2017). Women in Philosophy: Quantitative Analyses of Specialization, Prevalence, Visibility, and Generational Change. Public Affairs Quarterly, 31(2), 83–106.

- Solomon, Miriam and John Clark (2009). CSW Jobs for Philosophers Employment Study. APA Newsletters: Newsletter on Feminism and Philosophy, 8(2), 3–6.

- Steele, Jennifer, Jacquelyn B. James, and Rosalind C. Barnett (2002). Learning in a Man’s World: Examining the Perceptions of Undergraduate Women in Male-Dominated Academic Areas. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 46–50 https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.00042

- The Pluralist’s Guide to Philosophy (2019). Program Recommendations. Retrieved from https://sites.psu.edu/pluralistsguide/program-recommendations/

- Thompson, Morgan, Toni Adleberg, Sam Sims, and Eddy Nahmias (2016). Why Do Women Leave Philosophy? Surveying Students at the Introductory Level. Philosopher’s Imprint, 16(6), 1–36.

- Valian, Virginia (1998). Why So Slow? The Advancement of Women. MIT Press.

- Van Camp, Julie C. (2004). Female-Friendly Departments: A Modest Proposal for Picking Graduate Programs in Philosophy. APA Newsletters: Newsletter on Feminism and Philosophy, 3(2), 116–120.

- Van Camp, Julie C. (2006, May). Deep Thought: For (Mostly) Men Only? Does it Matter? Presented at the Pacific Meeting of the Society for Women in Philosophy (SWIP), UCLA.

- Van Camp, Julie C. (2015). Tenured/Tenure-Track Faculty Women at 98 U.S. Doctoral Programs in Philosophy. Retrieved from https://web.csulb.edu/~jvancamp/doctoral_2004.html

- Walker, Margaret (2005). Diotima’s Ghost: The Uncertain Place of Feminist Philosophy in Professional Philosophy. Hypatia, 20(3), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2005.tb00492.x

- Ward’s Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio, 490 U.S. 642 (1989).

- Weinberg, Justin. (2015). Criticisms of the Philosophical Gourmet Report [blog post]. Retrieved from http://dailynous.com/2015/12/18/criticism-of-the-philosophical-gourmet-report/

- West, Jevin D., Jennifer Jacquet, Molly M. King, Shelley J. Correll, and Carl T. Bergstrom (2013). The Role of Gender in Scholarly Authorship. PLoS ONE, 8(7), e66212. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066212

- Wheeler, Gregory (2012a, April 17). Manufactured Assent: The Philosophical Gourmet Report’s Sampling Problem [blog post]. Retrieved from http://choiceandinference.com/2012/04/17/manufactured-assent-the-philosophical-gourmet-reports-sampling-problem/

- Wheeler, Gregory (2012b, April 19). More on the Educational Imbalance Within the PGR Evaluator Pool [blog post]. Retrieved from http://choiceandinference.com/2012/04/19/more-on-the-educational-imbalance-within-the-pgr-evaluator-pool/

- Wheeler, Gregory (2012c, April 24). Two Reasons for Abolishing the PGR. Retrieved from http://choiceandinference.com/2012/04/24/two-reasons-for-abolishing-the-pgr/

- Wilhelm, Isaac, Sherri Conklin, and Nicole Hassoun (2017). New Data on the Representation of Women in Philosophy Journals. Philosophical Studies, 175(6), 1441–1464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-017-0919-0

- Wilshire, Bruce (2002). Fashionable Nihilism: A Critique of Analytic Philosophy. State University of New York Press.

- Wilson, R. (2005, May 20). Deep Thought, Quantified. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Deep-Thought-Quantified/24716

Notes

See, e.g., blog posts on www.beingawomaninphilosophy.wordpress.com.

We do not take this, in any way, to be an endorsement of the Gourmet Report’s methodology or rankings.

We look at PGR Top-20 versus PGR programs in order to understand whether the apparent differences in the proportions of women are statistically significant and to go beyond on existing research focusing on PGR Top-20 programs only (Haslanger 2009; Van Camp 2004; 2015). See Methods Section for additional details.

Similar patterns are reported in Australia where efforts have been made to document the representation of women in philosophy. For example, The Australasian Association of Philosophy suggests women comprise 55% of students enrolled in undergraduate courses in Australian Universities (Goddard 2008d). See also Dodds & Goddard (2013), and Baron, Dougherty, & Miller (2015). Goddard (2008a; 2008b; 2008c; 2008d) showed that while women comprise 42% of earned PhDs in Australian Universities, they account for 33% of new hires and 23% of total Philosophy faculty. For more on the representation of women philosophy faculty in non-US institutions, see Rini (2013) and Bowell (2015). However, we limit our discussion primarily to the United States.

See especially Saul (2013). For more hypotheses, see Moulton (1989), Hall (1993), Rask & Baily (2002), Steele, James, & Barnett (2002), Walker (2005), Haslanger (2008), Morganson, Jones, & Major (2010), Rooney (2010), Dotson (2011), Antony (2012), Paxton et al. (2012), Buckwalter & Stich (2014), Schouten (2015), Leslie, Cimpian, Meyer, & Freeland (2015), Dougherty, Baron, & Miller (2015), Thompson et al. (2016).

For more on percentages of women PhD students in philosophy departments, see The APA Guide to Graduate Programs in Philosophy (2015a) located online. See also Jennings (2016) discussion of philosophy PhD programs that rank well in terms of the proportion of PhD’s awarded to women and minorities. For more on job placement, see Jennings (2014a; 2014b; 2015a; 2015b). See De Cruz (2018) for a more recent discussion on prestige bias and the hiring of philosophy PhDs as tenure track faculty. For a discussion of choosing inclusive PhD programs in philosophy, see Van Camp (2004).

Wilhelm, Conklin, & Hassoun (2017) report that philosophy journals do not publish women in proportion to their presence as philosophy faculty. Yet, publishing is essential to academic hiring, tenuring, and promoting (Allen-Hermanson 2017; O’Neill & Sachis 1994). If women have difficulty getting published in philosophy journals, then this serves as one possible explanation for why the proportions of women philosophy faculty decrease as one ascends the professional hierarchy in terms of both job ranks and ranks associated with program prestige. However, we need more data to test this hypothesis. For more on professional performance and participation of women in philosophy, see Irvin (2014) and Schwitzgebel (2015a; 2015b; 2015c). For more on the representation of women authors in philosophy journals, see West, Jacquet, King, Correll, & Bergstrom (2013), Krishnamurthy (2017), Krishnamurthy, Liao, Deveaux, & Dalecki (2017), Saul (2017), and Schwitzgebel & Jennings (2017).

For a discussion of what data can teach us about the representation of women in philosophy, see Benétreau-Dupin & Beaulac (2015).

In 2004, Julie Van Camp began collecting faculty data on 98 philosophy departments and continued to do so as of 2015. Haslanger’s 2009 data are available on the project website: www.women-in-philosophy.org.

Given these concerns, one may well worry about the utility of these rankings, especially for graduate students or potential faculty hires seeking to make decisions about what departments to join. For replies to Bruya (2015), see Leiter (2012; 2015). For additional discussion, see Wilshire (2002), Walker (2005), Wilson (2005), McAfee (2007), Frodeman & Rowland (2009), McAfee (2010a, 2010b, 2011), Saul (2012), Wheeler (2012a, 2012b, 2012c), McAfee (2014), Weinberg (2015), Heck (2016), and Aboulafia (2018). While we do not in any way endorse the PGR’s methodology or rankings, the performance of these programs by percent women faculty is worth investigating because we might reasonably expect the most prestigious programs, according to the PGR survey, to have the lowest proportions of women faculty in the discipline, especially given findings in the existing literature (Schwitzgebel & Jennings 2017).

See, e.g., blog posts on www.beingawomaninphilosophy.wordpress.com

While there are alternative contemporary rankings for philosophy departments in the US, including The Pluralist’s Guide to Philosophy (TPGP 2019), we cannot use these for longitudinal analysis because no historical data exist for other ranking systems. The Pluralist’s Guide to Philosophy is a relatively new initiative, which does not provide distinctive rankings for philosophy departments. Instead, it provides clusters of alphabetically listed names of philosophy programs, which perform well on different measures (See TPGP 2019). See Appendix I for a brief analysis of TPGP programs for which we have 2015 data. Other measures, such as the QS World University Rankings, only provide disciplinary rankings for recent years (See QS 2019). We are hesitant to utilize general rankings of universities because we worry the results would not adequately reflect the nuanced trends in the discipline that can be found using rankings created with some knowledge about philosophy as a discipline.

Some may find discrepancies between the percentages of men and women in philosophy departments reported in this paper and the actual percentages of men and women in these philosophy departments. Please note that our data represent a cross section of the discipline at the time faculty data were collected from department websites. Of course, faculty continually enter and exit departments, so we only claim to present a recent overview of the programs we evaluate at the time our data were collected. Notes on data collection methodology and how we classified professors for a few individual schools are included in the actual database, see: www.women-in-philosophy.org.

We recognize that the title of Lecturer refers to the equivalent of a tenured/tenure track faculty position in the UK and Australia, while the title of Associate or even Full Professor may not refer to a full-time faculty person with a tenure track position in some institutions outside of the US. Our discussion of these titles and their categorizations are limited to faculty employed in the US.

Sally Haslanger counted as “full time professor” those who are on tenure track and may have counted those who are adjuncts or lecturers as well as some affiliated professors as full time.

Many philosophy departments did not include this information on their department websites at the time the data were collected. Including graduate students and post-docs in our study would therefore likely lead to inaccurate results due to a non-representative sample. We focus instead on lecturers and adjuncts, who are typically listed on department websites, because of their role as instructors in the department.

Throughout this paper, a graph may appear different from the corresponding graph on the project website: www.women-in-philosophy.org. For the purposes of this paper, we excluded Emeritus and Visiting Professors from our calculations, but they are included in the calculations for the graphs on the website. Please also note that, for all data, we utilized data from department websites, which evolve continually as faculty join and leave departments for various reasons. Our data represent a snapshot of 98 departments in 2015.

One note for readers experienced with Poisson regressions and other statistical methods. Throughout the paper we use Poisson regressions to compare the proportions of women in different job types and at different kinds of programs. Yet, Poisson regressions only use integers. So, this might initially seem confusing. The use of offset variables allows us to compare, for a simplified example, the total number of women over the total number of positions (X/Y), which gives the same information as proportions but only utilizes integers. This method is widely accepted as a standard for the analysis of count data which we have on hand, the number of men and women at each program and the number of total positions in that program. For some introductory details on the uses of Poisson regressions, see Coxe, West, & Aiken (2009). Because our data do not have a normal distribution, a linear regression would not be an appropriate statistical method for analyzing our data, since linear regressions assume a normal distribution. Furthermore, we do not employ the widely used t-test to simply compare two proportions, since this method delivers only approximate results and could fail to detect statistically significant differences due to lack of power. The Poisson regression is both a more sensitive statistical test and more well suited to our data. We hope this clarifies our use of Poisson regressions throughout.

Throughout we report Confidence Intervals (CI) in addition to strength of significance indicated by p-values, as different readers will be familiar with different norms around reporting statistics. The following key indicates strength of the reported statistical results: p > 0.05 is not significant and is clearly stated as such throughout; p ≤ 0.05 is weakly significant (*); p ≤ 0.01 is moderately significant (**); p ≤ 0.001 is highly significant (***).

Between 2004 and 2015, the chance of an increase in the number of women at an unranked program is 1.02 (CI: 1.01, 1.04)***, at a PGR program is 1.03 (CI: 1.02, 1.04)***, and at a PGR Top-20 program is 1.03 (CI: 1.01, 1.04)*** for every additional year.

In departments where men left and were not replaced, the percentage of women would appear to increase. If so, the statistically significant increase in the proportions of women faculty in philosophy departments would not be due to an increase in the number of women.

Between 2004 and 2015, the chance of a decrease in the number of men at unranked programs is 1.01 (CI: 1.01, 1.02)** for every additional year.

For All Programs, women are 2.01 (CI: 1.69, 2.38)*** times more likely to work as Assistant Professors than Full Professors and 1.53 (CI: 1.29, 1.81)*** times more likely to work as Associate Professors than Full Professors. Also, women are 1.31 (CI: 1.07, 1.62)** times more likely to work as Assistant Professors than Associate Professors. At unranked programs, women are 1.82 (CI: 1.43, 2.32)*** times more likely to work as an Assistant Professor and 1.28 (CI: 1.01, 1.61)* more likely to work as an Associate Professor than a Full Professor. Also, women are 1.42 (CI: 1.03, 1.96)* times more likely to work as an Assistant Professor than an Associate Professor. At PGR ranked programs, women are 2.07 (CI: 1.65, 2.61)*** times more likely to work as an Assistant Professor and 1.72 (CI: 1.35, 2.19)*** more likely to work as an Associate Professor than a Full Professor. At PGR Top-20 programs, women are 2.13 (CI: 1.58, 2.87)** times more likely to work as an Assistant Professor and 1.72 (CI: 1.27, 2.34)** more likely to work as an Associate Professor than a Full Professor.

Compare also the proportions of women philosophy faculty who are lecturer/adjuncts to those who are tenured/tenure track for each program type. For Non-PGR programs, we find nearly 19% women in lecturer/adjunct positions and 29% women in tenured/tenure track positions. For PGR Top-20 ranked programs, we find 25% women in lecturer/adjunct positions and 22% women in tenured/tenure track positions. For all PGR ranked programs, we find around 24% women in both lecturer/adjunct positions and in tenured/tenure track positions. The differences between the proportions of women who are tenured/tenure track professors and lecturer/adjuncts are statistically significant for unranked programs but not PGR Top-20 and PGR ranked programs generally. Women are 1.49 (CI: 1.10, 2.05)** times more likely to work as tenured/tenure track professors than as lecturer/adjuncts at unranked programs.

Women are 1.19 (CI: 1.03, 1.38)* times more likely to hold an academic position at unranked programs than at PGR Top-20 programs.

Women are 1.27 (CI: 1.08, 1.49)** times more likely to hold a tenured/tenure track position at unranked programs compared to PGR Top-20 programs, and 1.16 (CI: 1.02, 1.32)** times more likely than at ranked programs overall.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for encouraging us to consider this point. In addition to using different statistical methods, we also considered a larger sample of "top" ranked programs (20 vs. 12) and found larger differences in the raw proportions of women faculty in ranked and unranked programs. These factors may also have contributed to the difference between our findings and those reported by Schwitzgebel and Jennings (2017). For more on prestige bias in philosophy, see De Cruz (2018).

Wilhelm et al. (2017) present data on the representation of women authorships in “Top” philosophy journals and argue that if women in philosophy have difficulty getting published, then we should not be surprised to discover that women would also have difficulty getting tenured and promoted. Publication is a key measure of research productivity for most tenuring committees (Allen-Hermanson 2017; O’Neill & Sachis 1994).

We thank an anonymous reviewer at Ergo for bringing this to our attention.

In Castaneda v. Partida (1977) the Court said that “‘if the difference between the expected value and the observed number [of black teacher hires] is greater than two or three standard deviations,’ then the hypothesis that teachers were hired without regard to race would be suspect” (see also Scanlan 2004: para. 2). This gives us a better sense of the standard to which the law might hold departments, which is especially relevant to the overall low proportions of philosophers racialized as black. See Botts, Bright, Cherry, Mallarangeng, & Spencer (2014). But, again, this standard may not be appropriate for academia where departments and universities have significant impacts on the size of the application pool.

Moreover, Valian (1998) argues that 25% is the threshold at which women and their labor become perceived as valuable to the workplace, so we might reasonably expect the glass ceiling to be set at this threshold. If so, we would expect women overall to have difficulty getting hired and tenured into the profession in proportions much over the 25% threshold, which is consistent with our findings for All Programs (at 26%).