Why Do Desires Rationalize Actions?

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

I begin the paper by outlining one classic argument for the guise of the good: that we must think that desires represent their objects favourably in order to explain why they can make actions rational (Quinn 1995; Stampe 1987). But what exactly is the conclusion of this argument? Many have recently formulated the guise of the good as the view that desires are akin to perceptual appearances of the good (Oddie 2005; Stampe 1987; Tenenbaum 2007). But I argue that this view fails to capitalize on the above argument, and that the argument is better understood as favouring a view on which desires are belief-like states. I finish by addressing some countervailing claims made by Avery Archer (2016).

Imagine that you frequently bet on the horses. I exclaim, “Why do you keep betting on the horses—that’s so irrational!”. You might reply, “It’s not for the money: I am running an experiment and want to know how bookmakers treat regular customers”. By explaining what you want, you might succeed in showing that your bets are rational after all. This fact reminds us of a simple truth: our desires make a difference to the rationality of our actions. Why is this true? Why do desires rationalize actions?

Some have claimed that the only plausible answer to this question appeals to the guise of the good, according to which desires represent their objects as having some favourable normative property (Quinn 1995; Stampe 1987; Schafer 2013). Perhaps this view best explains why desires rationalize actions. In this paper, I contrast two formulations of the guise of the good and consider which best explains why desires rationalize actions. The central goal is not to argue for the guise of the good as a whole, but rather to evaluate which of these two formulations of the view can best complete this particular explanatory task. But since this is probably the most important argument for the guise of the good, this is a crucial issue for the view.

In Section 1 I present the above argument for the guise of the good in slightly more detail. In Section 2 I address the view that desires are appearances of the good. Then, in Section 3, I discuss the view that desires are beliefs about the good. These two sections make a case for the latter view over the former. Finally, in Section 4 I address some countervailing claims made by Avery Archer.

1. The Argument

1.1. The Central Question

Imagine that Evita prefers adventure, to beer, to caffeine. And imagine that her only options are ascending the Alps, booking a brewery tour, or calling at a cafe. And imagine that ascending the Alps satisfies her desire for adventure, booking a brewery tour satisfies her desire for beer, calling at the café satisfies her desire for caffeine, that none of these options satisfies any other desire, and that Evita knows all this. Under these circumstances, rationality requires Evita to ascend the Alps.

Evita’s situation is obviously unrealistically simple, and because it is so simple, it may be hard to imagine her being irrational and choosing any option but the rational one. But it nonetheless seems that there is a rational choice for her to make. In that respect, Evita’s situation seems to be a simplified model of ours: we have many desires (equivalently: wants, preferences), and these desires bear on what it is rational for us to do. They bear on that issue in proportion to their strengths, and bear on that issue in combination with our beliefs about the extent to which our options might satisfy those desires.

At least, this is the standard picture in decision theory. Perhaps you don’t accept this theory of rationality in all its details, but so long as you accept the very modest claim that what it is rational for you to do depends at least partly on what you want, that’s enough for my purposes here. Let’s capture this modest claim more succinctly as the claim that desires rationalize actions. But why is this true? This is our central question: Why do desires rationalize actions?

Before we look at possible answers to this question, I should say something about how I am thinking of rationality. I am thinking of rationality in a fairly simple pre-theoretical manner, as acting in a manner that makes sense, given your perspective at the time. I am equally thinking of rationality as the thing that decision-theory aims to analyse. But probably the most important thing to stress is just that I am thinking of rationality as always being contingent on your own perspective: in that sense, I am thinking of rationality as something like structural rationality rather than substantive rationality (see, e.g., Scanlon 2007 for this distinction). There is a great deal of very sophisticated discussion about how to understand structural rationality in a more precise manner than this (e.g., Broome 2013; Kiesewetter 2017; Kolodny 2005; Parfit 2011; Scanlon 2007). Thankfully, everything I say in this paper is relatively independent of those debates. The point is easiest to see once my answer to the central question is on the table, and so I relegate my brief remarks on the issue to the end of Section 3.

1.2. The Standard Theory

We might hope to answer our central question partly by appeal to the nature of desire. The standard theory of desire is that a desire that P is a state which disposes you to do things that you believe will secure P (Smith 1987; 1994; Stalnaker 1987: 15; for criticism, see, e.g., Arpaly & Schroeder 2014: 111–116; McDowell 1998; Schueler 1995). For example, given that Evita has a desire for adventure, and believes that ascending the Alps will secure adventure, Evita is disposed to ascend the Alps.

For this reason, the standard theory entails that Evita is disposed to do the very thing that it is rational for her to do. That seems plausible (cf. Davidson 2004; Dennett 1987). The standard theory also entails something else plausible: that it is possible to be irrational. According to the standard theory desires are dispositions, and dispositions are not always realized. So the defender of the standard theory can say that there are various conditions that have to be in place for desiderative dispositions to be realized—for desires to result in action—and sometimes the absence of these conditions entails an absence of rationality (Sinhababu 2011). For example, perhaps Evita has depression, and this leaves her desires intact but prevents them from realizing their motivational influence (Swartzer 2015). Her depression might make her irrational by lowering the motivational influence of her strong desire for adventure.

So the standard theory entails that people are disposed to be rational, but only fallibly so. But despite these plausible implications, the standard theory of desire does not provide us with an answer to our central question. It permits that we might irrationally fail to act on our desires, but it does not explain why doing so is irrational. That is, if desires are merely dispositions to act in certain ways, then acting on a desire is no more rational than realizing any other disposition you have. Perhaps Evita is also disposed to get sleepy in the afternoons, to get bags under her eyes when tired, to squint in bright light, and to trip over when distracted. These dispositions are non-rational dispositions: there is nothing rational about her realizing these dispositions, nor anything irrational about her for failing to realize them. What is different about the dispositions that constitute her desires? Evita may well have other dispositions which are positively irrational. Perhaps she is disposed to affirm the consequent, to be biased towards the status quo, and to be overconfident in her own views. Realizing these dispositions does not make her rational, but instead the reverse. Again, why are desiderative dispositions different?

In short, only some dispositions are rational dispositions, and so far as the standard theory of desire goes, we have no explanation of why desires belong to the privileged kind. This doesn’t make the standard theory false, but does make it crucially incomplete.

1.3. The Guise of the Good

Since the standard theory of desire alone doesn’t obviously provide a satisfactory answer to our central question, we might supplement or replace it with some other theory. And one long-standing theory about desire is the guise of the good (Anscombe 1963: 75; Aquinas ST I-II.1.1; DV 24.2; Davidson 2001: 22–23; Moss 2012; Raz 1999; 2010). This view can be formulated in many different ways, but the broad thought is that desires represent their objects as having some normative property. Some have claimed that this view provides the best explanation of why it is rational to act on our desires—we might think that the guise of the good provides the best answer to our central question. If so, this would provide an abductive argument for the guise of the good (Quinn 1995; Stampe 1987; Schafer 2013).

This is an interesting argument. One way to begin evaluating it is to ask what its conclusion ought to be. In the next two sections I will critically contrast two possible ways of filling out this argument. They differ in exactly how they understand the guise of the good, and in turn, differ in exactly how they use the guise of the good to answer our central question.

Before I turn to that task, we should note something that our possible options will have in common. Both understand the guise of the good as a constraint on desire. Sometimes the guise of the good is formulated as the view that actions are always undertaken under the guise of the good (e.g., Raz 1999: 22–23; 2010: 111; Setiya 2007: 16–17), or formulated as the view that we intend actions only under the guise of the good (perhaps Aquinas ST I-II.1.1). But the above argument all hinged on the rationalizing force of desire, and so its direct conclusion is a claim about desire and not about action or intention.

I now turn to our two options.

2. Desires as Appearances

Recently, the most popular way to formulate the guise of the good has been as the claim that desires are appearances of the good (Oddie 2005; Shafer 2013; Stampe 1987; Tenenbaum 2007; see also Moss 2012). The idea is that just as perceptual states present things as being a certain way (e.g., the wall as red), and just as intellectual “seemings” states present things as being a certain way (e.g., 0.999… as less than 1), desires present their objects as good.[1] Such presentational states are independent of your beliefs: you can distrust how things seem to you, as when you think you are subject to a visual illusion, or when you know that the intellectual appearances are deceptive. The thought is that when we desire something it seems good to us, though we might believe those appearances to be misleading. Let’s call the view that desires are such presentational states presentationalism.[2]

Presentationalism might seem to answer our central question. Presentational states can clearly rationalize belief (see, e.g., Huemer 2007). For example, if you perceive the wall as red, that might well make it rational to believe that the wall is red. So if we think that desires are presentations of the good, it might seem plausible that such states can rationalize action (e.g., Stampe 1987: esp. 362). If P is presented to you as good, isn’t it rational to do things that you think will promote P? In this way, presentationalists hope to explain the rationalizing force of desire on the model of the rationalizing force of presentational states. As such, we might think that there is a good argument for presentationalism: it best explains the rationalizing power of desire.

But we should not accept presentationalism. I shall give two reasons to reject it, and then independently show that it provides a poor answer to our central question.

First, presentationalism understates the rational responsiveness of desire (see also Gregory 2017c: 214). If I ask whether you want to visit Tonga this summer, you might investigate the issue and deliberate at length in order to decide whether you want to go (and if so, how strongly). The claim that our desires are sensitive to deliberation may be controversial with respect to our non-instrumental desires, but it is undeniable with respect to our instrumental desires. We form instrumental desires by rationally combining our prior desires with our beliefs, and so it obviously follows that we form instrumental desires in light of the beliefs we hold and the inferences we have made about how our beliefs interact with our desires. So our instrumental desires, at least, are rationally responsive. But if such desires are presentational states, they should not be rationally responsive in this manner. How things are presented to us is not something we can significantly change by acquiring further information, or by reasoning. For example, no amount of reasoning will change the colours things perceptually appear to have. So it is not plausible that all desires are presentational states.

One might object that presentational states can be influenced by our beliefs. For example, if you are told that there are snakes nearby, this might make nearby vines look more snake-like. But first, the evidence for such “cognitive penetration” is far from decisive—see Firestone and Scholl (2015) for scepticism. Second, even if our beliefs do affect our presentational states in this manner, this falls short of explaining the rational responsiveness of desire. Our instrumental desires can quite clearly be changed by inference. I can deliberate about my goals, and settle on appropriate means to them, and thereby come to desire those means. But cognitive penetration is a merely causal process, not an inferential one. One way to see this is to note that such cognitive penetration is rationally unconstrained: you might make nearby vines look more snake-like by telling me that there are snakes around, but you might achieve the very same effect by telling me that there are not snakes around: the mere mention of snakes might be enough to put me on edge. But our formation of instrumental desires is not a merely causal process like this, but instead a rational process of inference.

The second (related) reason to reject presentationalism mirrors a common objection to presentational theories of emotion (see, e.g., Brady 2013: 112; Helm 2015). Presentationalism (about desire) lacks the resources to explain the possibility of irrationality in desire (cf. Stampe 1987: 359). This criticism is somewhat ironic, since one of the main attractions of presentationalism is supposed to be that it makes room for desiderative failures (e.g., Tenenbaum 2007: Chapters 6, 7, 8). For example, the view is supposed to be attractive because it makes room for the possibility that an agent’s value beliefs might fail to align with her desires. According to presentationalism, this can occur just because one can believe the appearances to be illusory (Tenenbaum 2007: Chapters 6, 7, 8).

But on reflection, presentationalism is less attractive here than it appears. Presentationalism does make room for the possibility that an agent might reject her desires. And since presentational states can be inaccurate, it also makes room for the possibility that a desire can be incorrect (when, e.g., self-destructive). But presentationalism does not make room for the possibility of irrationality in desire. Presentational states cannot be irrational. No matter what the circumstances, if it perceptually appears to you that the wall is red, you are not irrational. Perhaps under some circumstances you might be irrational to believe this appearance, and perhaps we can say that your perceptual faculties are malfunctioning or inaccurate. But these claims fall short of saying that your perceptual state is itself irrational. So if desires were presentational states, no desire could be irrational.

This might seem like a welcome conclusion: isn’t it true that desires—such as for cold showers—are not subject to rational assessment? I am doubtful of this claim, for reasons given by Parfit (2011: 54–56). But we can set this aside: even if some desires are beyond rational assessment, other desires clearly are rationally assessable. Since presentationalism treats all desires as presentational states, it cannot permit even this modest claim.

For example, intransitive preferences are clearly irrational. Imagine that you prefer to go a conference by train than plane (because it is better for the environment), prefer to go to the conference by plane than not at all (because the conference will be worth the short journey), but also prefer not to go to the conference at all than to go by train (because the conference will not be worth the long journey). An agent with these preferences seems irrational (see, e.g., Broome 2006). But presentationalism cannot allow this. If you are subject to some illusion whereby A looks better than B, B looks better than C, and C looks better than A, you are not thereby irrational, any more than you would be irrational for being subject to a similar illusion about length. So presentationalism cannot explain the irrationality of intransitive preferences.

Or, for another example, if you desire that E, and believe that M leads to E, you should rationally desire that M (see, e.g., Broome 1997). An agent who fails to desire the known means to their ends seems irrational.[3] But again, presentationalism cannot allow this. If it appears to you that E is good, and you believe that M causes E, you are not irrational if M does not seem good to you. We are never under any positive rational requirements to form new presentational states. So again, presentationalism cannot explain the irrationality of failing to desire the means to our ends.

The two arguments above may seem local to our instrumental desires: it is our instrumental desires that are most obviously sensitive to information and reasoning, and our instrumental desires that are most obviously vulnerable to criticisms of irrationality. So in response, the presentationalist might restrict their theory, offering it as a theory of only non-instrumental desires. But this move is unattractive for three reasons. First, it is not wholly clear if it would avoid the objections above. Intransitive preferences, for example, seem to be irrational even if when non-instrumental. Second, it forces us to accept a disjointed theory of instrumental and non-instrumental desires, and it seems that a more unified theory would be better if one is available: the rival theory I discuss below need not pay this same cost. Third, most importantly, remember that presentationalism is supposed to explain the rationalizing power of desire. But if it does not extend to instrumental desires, it is not clear how it might explain the rationalizing power of such desires. Since instrumental desires do seem to rationalize actions—they rationalize the pursuit of money, for example—the presentationalist who constrains their theory in this way will fail to fully explain the rationalizing power of our desires as originally advertised.

The two arguments above aim to show that presentationalism is false: it offers a theory of desire that cannot make good sense of central features of desire, such as their sensitivity to information and reasoning and the possibility of irrationality in desire. The third problem with presentationalism is that it fails as an answer to our central question. The central question, remember, was to explain why it is rational to act on our desires. Presentationalists hope to explain this by appeal to the fact that desires are appearances of the good, in combination with the fact that presentational states have the power to rationalize belief. But when stated like this it should be obvious that presentationalism would not explain how desires rationalize actions, but instead explain how desires rationalize beliefs, and that is not what we hoped to explain.

That is, according to presentationalism, the desire that P is a presentational state in which P appears good. But the general model we are working on is the model on which the appearance as of P rationalizes the belief the P. So according to presentationalism, the primary rational upshot of a desire that P should be the belief that P is good. But this is wrong.

First, it is doubtful that desires rationalize beliefs in this manner. Imagine that I ask you why you think that giving money to Oxfam is a good thing to do, and you reply that you think this because you want to give them money. This seems like an inappropriate answer. But in general, perceptual states should rationalize beliefs which share their contents, and so if desires represent their objects as good, a desire that P should rationalize the belief that P is good.

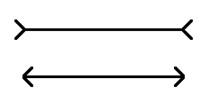

Second, desires do seem to rationalize actions, unlike presentational states. What it is rational for you to do seems to depend directly on what you want. But what it is rational for you to do does not depend directly on your presentational states at all. For example, imagine that you are presented with the Muller-Lyer lines (Figure 1), and some decision (e.g., whether to accept a bet) hinges on their respective lengths. Though the first line seems longer, let’s imagine that you know about the illusion, and have even measured the lines in this case and confirmed that they are really equally long. Under such circumstances, it seems that the appearances are irrelevant to what it is rational for you to do: the rationality of your actions will depend only on what you believe about the lines, and not how they appear. Parallel reasoning suggests that if A seems to you to be better than B, that alone tells us nothing about whether you ought to pursue A: everything depends on whether you accept these appearances. When we rationally evaluate your actions, we do not take into account your presentational states, only your beliefs and desires. It is useful to think of decision theory here, which aims to analyse rationality. It presents a plausible theory of rationality that appeals only to an agent’s beliefs and desires, not at all to their presentational states.

There is an objection to this last argument that I should address. An objector might suggest that our central goal was to understand why desires make actions rational. But they might think that showing an action to be rational, in the relevant sense, is merely to show that it is intelligible, that it makes sense to the agent in some way (this is certainly how some defenders of the guise of the good put things: see, e.g., Johnson 2001). And we might think that presentational states can at least make actions intelligible independently of the contribution they make to an agent’s beliefs. For example, perhaps we can at least understand how someone might come to bet on the first Muller-Lyer line being longer if it appears to them that way, even if we know that they know full-well that those appearances are misleading. In turn, perhaps parallel reasoning tells us that normative presentational states can make actions intelligible.

We should be careful with this objection. One thing that gives it false credibility is the fact that under some circumstances (e.g., when tired) you might form the belief that the first line is longer, despite knowing, in the abstract, about the Muller-Lyer illusion. So we must be careful with the claim that your behaviour can be rendered intelligible by how things appear to you: sometimes it can, but only because the appearances are (irrationally) influencing your beliefs. We should instead focus on the case where you definitely believe that the lines are of equal lengths, and still make choices that rely on this being false. With respect to this kind of case, it strikes me that such behaviour really would be unintelligible. If you are fully aware that the two lines are of equal lengths, what sense can we make of your betting that the top line is longer? In turn, it would strike me as unintelligible if someone acted on the normative appearances if they failed to accept those appearances as veridical.

But in case this is not so intuitive to others, there is a second more decisive problem with this objection. Our central question concerned the capacity of desires to rationalize actions. But the objection relied on the thought that appearances can render actions intelligible. More is required to make an action rational than to make it intelligible: behaviour might be irrational but intelligible, if, for example, it exemplifies an understandable kind of human bias (cf. Johnson 2001: 190–191). To this extent, even if appearances could render actions intelligible, that would not suffice to show that they can render actions rational: they might render acts intelligible only by showing them to result from an understandable kind of irrationality. And to be clear, our central question really does concern rationality rather than intelligibility: desires make actions sensible, not merely predictable (and again, think of decision theory, which is definitely intended as a theory of rationality). So even if appearances could render actions intelligible (again, which I doubt), that would not show that they can render actions rational. And that stronger claim is not plausible: acting on the appearances, against your beliefs, is surely irrational.

In summary, there are at least three reasons to doubt presentationalism. Presentationalism cannot explain the way in which our desires are sensitive to information and reasoning. Presentationalism cannot explain the possibility of irrationality in desire. And most crucially for our purposes, presentationalism cannot adequately answer our central question: presentationalism suggests that desires rationalize beliefs, rather than actions, and this is not plausible. Pace presentationalism, the primary rational output of desire is action, not belief.

In the face of these objections, the presentationalist might weaken their claims. They might agree that desires are not literally appearances of the good, but maintain that they are nonetheless similar to such states. But in this form the view is too vague to be able to answer our central question, as originally advertised. After all, if the presentationalist says that desires are similar to presentational states only in that they have the power to rationalize something, that at best asserts, rather than explains, the fact that desires can rationalize actions. But if the presentationalist says that desires are similar to presentational states in other respects which genuinely explain why they rationalize things, they need to say in which respects they are similar, so as to show that they can be similar enough to rationalize something without being so similar as to rationalize only belief. Without such details, the view fails to explain why desires rationalize actions.

3. Desire as Belief

If we want to go beyond the standard theory of desire and endorse some theory in the vicinity of the guise of the good, we should not endorse presentationalism. Instead, I suggest that we should endorse desire-as-belief, according to which desires are beliefs rather than appearances of normative properties (Campbell 2018; Gregory 2017a; 2017c; Humberstone 1987; Little 1997; McNaughton 1988: 106–117; Price 1989; see also Scanlon 1998: 7–8, 37–49). In what follows I point to some reasons to think that desire-as-belief is preferable to presentationalism as an answer to our central question.

It is worth repeating that my goal is not to argue comprehensively for any version of the guise of the good, but rather to make progress with the internal debate as to which formulation of that view is best. To that extent, my primary goal is to argue that desire-as-belief answers our central question, and does so in a manner better than presentationalism, and not to provide a comprehensive evaluation of desire-as-belief.

To fully evaluate desire-as-belief, we might want to investigate other attractive features of the view. For example, perhaps it can explain how moral beliefs can motivate us, without our having to abandon the attractive view that all motivation is explained by desire (for discussion, see Gregory 2017a; McNaughton 1988; Smith 1994; esp. 111–125). Or for another example, perhaps it can allow us to explain how we get self-knowledge of our desires: by attending to what we think is good (Byrne 2011: Section 4; Suikkanen in press; cf. Ashwell 2013; Fernández 2007; Moran 2001: 114–16). And perhaps there are other arguments for desire-as-belief (e.g., Bramble in press; Campbell 2018; Gregory 2017c: 202–203; Humberstone 1987). Moreover, to fully defend desire-as-belief, we would need to address various objections it faces. For example, it might seem that desire-as-belief conflicts with the idea that desires and beliefs have different “directions of fit” (Smith 1994: 111–116). Or it might seem that desire-as-belief conflicts with the idea that children and animals can have desires without having normative beliefs. Or it might seem that desire-as-belief is inconsistent with the possibility of perverse desires (Stocker 1979; Velleman 1992). Or it might seem that desire-as-belief is inconsistent with the possibility of irrationality in desire, such as akrasia (Smith 1994: 117–125). Or it might seem that desire-as-belief is inconsistent with decision theory (Lewis 1988; 1996). These objections are all interesting and deserve responses.[4]

But insofar as our goal is just to evaluate how the guise of the good ought to be formulated so as to capitalize on the argument with which I began (§1), none of these issues are directly relevant. My claim in this paper is that the best argument for the guise of the good supports only desire-as-belief, not presentationalism. If desire-as-belief is unattractive or objectionable for independent reasons, then my argument in this paper would contribute a premise in a broader argument against the guise of the good. As you might guess, this is not my goal in developing the arguments here, but you need not share my goals to endorse my central claim here, which is really the conditional claim that if we endorse the guise of the good, we should do so in the form of desire-as-belief.

With these caveats noted, I return to our central topic. Desire-as-belief promises to provide a very simple explanation of why desires rationalize actions. It is an absolutely central principle of rationality that you should live up to your own normative beliefs. To do otherwise is to be akratic, and akrasia is the paradigm case of irrationality: it involves inconsistency between one’s normative beliefs and one’s actions. Since desire-as-belief tells us that desires are normative beliefs, it combines with the injunction against akrasia—the enkratic principle—to tell us that it is rational to act on your desires. This line of thought is simple and compelling: unlike presentationalism, desire-as-belief promises to explain why desires rationalize actions, and it does so via a principle of rationality that absolutely everyone ought to accept. So we might argue for desire-as-belief on the grounds that it best explains why desires rationalize actions.

But there is a problem. We have been thinking about the guise of the good, and so we might naturally think of desire-as-belief in the following way:

Desire-as-belief*: To desire that P is to believe that P is good.

In contrast, the enkratic principle is standardly formulated in (roughly) the following way (e.g., Broome 2013: 90; Ewing 1947: 120–121):

The Enkratic Principle: Rationality requires you to φ if you believe that you ought to φ.

These two views don’t obviously combine to explain why desires rationalize actions. Desire-as-belief* tells us that desires are beliefs about the good, whereas the Enkratic Principle makes no claims about such beliefs, only about ought beliefs. So how could the Enkratic Principle possibly combine with desire-as-belief* to explain why desires rationalize actions?

This problem can be fixed. Though the guise of the good is typically understood as saying that desires represent their objects as good, we might instead understand desire-as-belief as saying that desires are beliefs about (normative) reasons (see also Gregory 2013). This would not be the guise of the good, as such, but it would be close enough: it is still a view on which desires represent their objects as having a favourable normative property. That is, we might understand desire-as-belief as follows:

Desire-as-belief: To desire to φ is to believe that you have normative reason to φ.[5]

But even with this modification, desire-as-belief still doesn’t combine with the Enkratic Principle to explain why desires rationalize actions: one makes a claim about reasons beliefs, the other a claim about ought beliefs. But we are closer. To complete the argument, we need to clarify our central question. We might seek to explain why we are rationally required to take actions that we most strongly desire to do, taking all of our desires into account. Alternatively, we might seek to explain why rationality favours every action to whatever extent it satisfies some desire we have. I take the possibilities in turn.

First, perhaps we are seeking to explain why we are rationally required to do whatever we most strongly desire to do. We can explain that via the Enkratic Principle, and the following claim, which is a natural extension of desire-as-belief:

Overall-desire-as-belief: To most strongly desire to φ is to believe that you ought to φ.[6]

Overall-desire-as-belief combines with the Enkratic Principle to explain why you rationally ought to do whatever you most strongly desire to do. It explains, for example, why it’s rational for Evita to ascend the Alps. If we want to explain why agents are rationally required to do whatever they most strongly desire to do, then Overall-desire-as-belief, combined with the Enkratic Principle, does the job.

The second possibility—which I find more compelling—is that we are seeking to explain why rationality favours actions to whatever extent that they satisfy desires. It is surely tempting to think of our central question in this way. Return to Evita. Since her desire for adventure is strongest, plausibly she rationally ought to ascend the Alps. But imagine that she instead books the brewery tour. We might think that this is irrational, since she prefers adventure to beer. But nonetheless, we might think that her action is at least more rational than calling at the cafe, since she prefers beer to caffeine. In order to explain this, we should endorse a view on which rationality favours every action to the extent that it satisfies a desire, so that rationality favours Evita booking the brewery tour to some extent, even if it doesn’t favour it as much as her ascending the Alps. Once we endorse this view, we can see that the requirement to do whatever you most strongly desire is just a consequence of the more general truth that actions are rationally favoured to whatever extent they satisfy desires (cf. Brunero 2010: 33–34; Schroeder 2008; 2009; see also Fogal 2018).

But once we agree to this, we should modify our understanding of the Enkratic Principle in a similar manner. The Enkratic Principle says that rationality requires us to do whatever we believe we ought to do (see, e.g., Broome 2013: 90). But just as I suggested that a desire can rationally favour an action without rationally requiring it, the same is true of our normative beliefs. Imagine you believe that you have conclusive reason to do A, less reason to do B, and still less reason to do C. Rationality might require you to do A, but if you do B instead, that is at least more rational than doing C.[7] Again, we might see the requirement to do what you believe you ought to do as just a consequence of the more general truth that actions are rationally favoured to whatever extent you believe you have reason to do them. So we might reformulate the Enkratic principle as follows:

The Enkratic Principle+: Rationality favours φing to the extent that you believe you have reason to φ.

The Enkratic Principle+ combines with desire-as-belief to answer our central question. Desire-as-belief tells us that desires are beliefs about reasons, and the Enkratic Principle+ tells us that rationality favours acting on such beliefs. These views together explain why rationality favours acting on our desires.

Let me summarize. The basic thought is that desire-as-belief says that desires are normative beliefs, and so rationality favours acting on our desires just because rationality condemns akrasia. Spelling this thought out more precisely requires us to take a stand on our central question: whether we are seeking to explain why actions are required if we most strongly desire to do them, or else to explain why actions are favoured to whatever extent we desire to perform them. In the former case desire-as-belief needs to be extended in a natural manner to combine with the Enkratic principle to answer the question. In the latter—more plausible—case the Enkratic principle can be extended in a natural manner to combine with desire-as-belief to answer the question. Either way, there is a plausible version of desire-as-belief, and a plausible version of the Enkratic principle, that combine to answer our central question. In turn, the argument with which we began supports desire-as-belief: there is an inference to best explanation for a version of desire-as-belief, since the view ably explains why desires rationalize actions. I conclude that desire-as-belief is preferable to presentationalism insofar as we seek a version of the guise of the good that explains why desires rationalize actions.

I said at the start that these claims are independent of various controversies about rationality. I can now explain that claim in slightly more detail. I shall take three central controversies about rationality, and show that none threatens my claims above. (If you are not interested in these debates, you could skip the remainder of this section.)

First controversy: John Broome argues that rationality only governs things within our control, and so only governs states of mind, and not actions (Broome 2013: 88–89, 151–152). If true, this would undermine our central question, since it entails that actions are never rational. And if true, this would also undermine the enkratic principles I discuss, since actions are never rational. But Broome’s view is plausible only to the extent that there are mental precursors to action that are the real subjects of evaluation when we seemingly rationally evaluate acts. For example, Broome might suggest that when we say an act is rational, we are really saying that the intention to act in that way is rational. But once we allow this, we can see that our central question, and the enkratic principle, could be modified in a manner compatible with Broome’s view: we could ask why desires rationalize intentions, and we could understand the enkratic principle as saying that normative beliefs rationalize intentions. From these claims, we might infer desire-as-belief just as I suggest. In short, since Broome’s view tells us to modify our central question and enkratic principles in perfectly parallel ways, it leaves my central argument intact.

Second controversy: Some authors have claimed that rational norms are wide-scope norms (e.g., Broome 2013; and see Kiesewetter 2017 for comprehensive discussion). Such authors claim that rational norms never favour single states of mind or acts, but instead only combinations of these, such as to (either not believe P or else not believe Q or else not believe P→Q) or else to (either not intend to φ or else not believe that you ought to φ). If true, this might undermine our central question, and our enkratic principles. But again, this is no great concern: if the wide-scoping view is right, we ought to modify our central question and enkratic principles in perfectly parallel ways, leaving my central argument intact. For example, we might infer that desire-as-belief is the best explanation of the rational requirement to [either φ or don’t desire to φ], given the enkratic principle to [either φ or don’t believe you ought to φ].

Third controversy: Some authors have claimed that attitudes which are themselves irrational place no new rational requirements on us. For example, they claim that irrationally forming a belief does not make it rational to accept the consequences of that belief. But again, this suggestion makes no significant difference to the basic argument that I have defended, since it would compel us to modify our central question and enkratic principles in just the same ways. To the extent that it is true, we should think of our central question as the question of why rational desires rationalize actions, and desire-as-belief explains that given an enkratic principle according to which rational normative beliefs rationalize actions.

In each case, the basic point is that these debates about rationality force us to revise both our central question, and the enkratic principle, in just the same way. So long as these two things march in step, desire-as-belief will emerge as a perfectly good explanation of the rational upshot of desire. So these difficult debates about rationality do nothing to undermine the reasoning according to which desire-as-belief, unlike presentationalism, can explain why desires rationalize actions.

4. Archer

Finally, I turn to two further objections made by Avery Archer (2016). Archer’s main argument is that our central question itself is misguided. But Archer first briefly argues in favour of presentationalism over nearby views such as desire-as-belief (2016: 3–4). As a result, his later main critical discussion focuses on presentationalism. But his reasons for preferring presentationalism to desire-as-belief are mistaken, and are mistaken in ways that mirror the mistakes in his main critical discussion.

In particular, Archer argues that presentationalism is preferable to desire-as-belief on the grounds that presentationalism can explain why it is rationally permissible to have conflicting desires (2016: 3–4; see also Tenenbaum 2007: 38–39). The idea is that since it is perfectly rational to be subject to conflicting perceptual appearances, presentationalism rightly entails that it can be rational to have conflicting desires. In contrast, since it is normally irrational to have conflicting beliefs, desire-as-belief wrongly entails that it is irrational to have conflicting desires. So Archer claims.

But first, though it is rational to be subject to conflicting perceptual appearances, we should remember that this is rational only because no combination of presentational states is irrational. This is just the claim that caused problems for presentationalism, above. Second, if I am subject to two conflicting perceptual experiences, I should think of at least one of them as presenting things incorrectly. But this is not the way things are with desire: when I have conflicting desires, I need not think of any of these desires as representing things incorrectly. My desires for beer and for health conflict, but I do not think either of these desires is mistaken: each of these things really is worthwhile in the relevant respects. Desires do not contradict one another as perceptual appearances can, but instead compete, and do so in a manner that leaves it open that each correctly represents something of genuine significance (cf. de Sousa 1974; Williams 1973).

But third, and most importantly, we must be very careful in interpreting desire-as-belief. Desire-as-belief says that to desire that P is to believe you have reason to bring P about. So imagine that you desire that P, but that you also have a conflicting desire that ¬P. If desiring that P is believing that you have reason to bring P about, your desire that ¬P should be understood as the belief that you have reason to bring ¬P about. It should be clear here that these beliefs are perfectly consistent: they can both be true, since you might well have reasons to bring P about and competing reasons to bring ¬P about. Here, your conflicting desires might just accurately represent a genuine normative conflict, and so could surely be rational. Desire-as-belief entails that conflicting desires are beliefs about conflicting reasons, and not conflicting beliefs about reasons. For this reason, it avoids Archer’s objection. The broader point is that when we think about desire-as-belief, we should remember that it is the whole content of the desire that is represented as favoured by reasons. If we imagine a desire with a more complex content—such as a negated content—we should remember that the negation modifies the thing favoured, not the favouring itself. That is why desire-as-belief is consistent with the fact that it’s rational to have conflicting desires.

With this point in hand, let’s turn to Archer’s main argument (2016: 9ff.). Archer claims that one can rationalize a course of action with a coin flip just as well as you can with a desire (2016: 12). For example, if I am deciding whether to cook Lasagne or Stroganoff this evening, I might decide by flipping a coin, and it seems perfectly rational for me to follow this procedure. But if that is so, then there is no special rationalizing force of desire to explain: desires rationalize no more than a purely arbitrary procedure, and in turn there is no need to endorse the guise of the good as an explanation of a special rationalizing force possessed by desire (2016: 9ff.).

Archer rightly recognizes a very natural response on behalf of the defender of the guise of the good (2016: 12–16). We might think that such a coin flip rationalizes later actions only because it is backed by some prior desire—some representation of goodness. But Archer argues against this suggestion (2016: 12–16). The idea is that such a prior desire would have to be a disjunctive desire, that is, a desire to cook either Lasagne or Stroganoff. But Archer argues that the guise of the good (understood as presentationalism) lacks the resources to explain how such a disjunctive desire could rationalize the later decision to cook just one of these foodstuffs (2016: 12–16). After all, the perception that either P or Q hardly rationalizes the belief that P.

But this line of argument is mistaken. Again remember that desire-as-belief says that to desire that P is to believe you have reason to bring P about. I take it that a disjunctive desire is a desire that P˅Q. If desire-as-belief is right, a disjunctive desire that P˅Q is the belief that you have reason to bring it about that P˅Q. And that belief surely does rationalize an action that brings P about. That is, a desire to cook either Lasagne or Stroganoff should be understood as belief that one has a reason to cook either Lasagne or Stroganoff, and this belief would rationalize the decision to cook either: cooking either allows you to comply with a reason you believe you have. Here, again, it is important to get clear about how desire-as-belief treats the contents of desire: it treats the whole thing as something favoured by reasons. Again, if we imagine a desire with a more complex content—such as a disjunctive content—we should remember that the disjunction modifies the thing favoured, not the favouring itself. That is why desire-as-belief is consistent with the thought that disjunctive desires rationalize actions.

Since desire-as-belief can explain how a desire for either Lasagne or Stroganoff would rationalize the decision to cook either, we can maintain the obvious response to Archer’s argument: coin-flips only rationalize actions when backed by desire, and in turn the rationalizing power of desire is indeed something which needs explaining.

5. Conclusion

In this paper I have argued that desire-as-belief represents a better answer to our central question than presentationalism. I began by outlining the main argument for the guise of the good: that we must think that desires represent their objects favourably in order to explain why they rationalize action. I then explained why presentationalism is nonetheless implausible: it cannot explain the sensitivity of desires to reasoning, cannot explain the possibility of irrationality in desire, and worst, fails to explain why desires rationalize actions. I then explained why desire-as-belief may be a more promising view. It explains why desires rationalize action by appeal to a familiar principle of rationality—Enkrasia. Finally, we should not be swayed by Archer’s arguments against desire-as-belief and more generally against our argument for desire-as-belief. Those arguments rely on mistaken assumptions about how desire-as-belief should analyse desires with complex contents.

Acknowledgements

For assistance with this paper, I thank audiences at Humboldt, Luxembourg, and St. Louis (at SLACRR), as well as colleagues at Southampton. Referees for this journal also provided very useful suggestions.

References

- Alvarez, Maria (2010). Kinds of Reasons: An Essay in the Philosophy of Action. Oxford University Press.

- Anscombe, Gertrude E. M. (1963). Intention (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press.

- Archer, Avery (2016). Do Desires Provide Reasons? An Argument against the Cognitivist Strategy. Philosophical Studies, 173(8), 2011–2027.

- Arpaly, Nomy (2000). On Acting Rationally against One’s Best Judgment. Ethics, 110(2), 488–513.

- Arpaly, Nomy and Tim Schroeder (2014). In Praise of Desire. Oxford University Press.

- Ashwell, Lauren (2013). Deep, Dark… or Transparent? Knowing Our Desires. Philosophical Studies, 165(1), 245–256.

- Bradley, Richard and Christian List (2008). Desire-as-Belief Revisited. Analysis, 69(1), 31–37.

- Bradley, Richard and H. Orri Stefánsson (2016). Desire, Expectation, and Invariance Mind, 125(499), 691–725.

- Brady, Michael (2013). Emotional Insight. Oxford University Press.

- Bramble, Ben (in press). Evaluative Beliefs First. In Mark Timmons (Ed.), Oxford Studies in Normative Ethics (Vol. 8). Oxford University Press.

- Broome, John (1997). Reasons and Motivation. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume, 71, 131–147.

- Broome, John (2006). Reasoning with Preferences? In Serena Olsaretti (Ed.), Preferences and Well-Being (183–208). Cambridge University Press.

- Broome, John (2013). Rationality Through Reasoning. Wiley Blackwell.

- Brunero, John (2010). The Scope of Rational Requirements. The Philosophical Quarterly, 60(238), 28–49.

- Byrne, Alex (2011). Knowing What I Want. In JeeLoo Liu and John Perry (Eds.), Consciousness and the Self: New Essays (165–183). Cambridge University Press.

- Campbell, Doug (2018). Doxastic Desire and Attitudinal Monism. Synthese, 195(3), 1139–1161.

- Davidson, Donald (2001). How is Weakness of the Will Possible? In Essays on Actions and Events (21–42). Oxford University Press.

- Davidson, Donald (2004). Problems of Rationality. Oxford University Press.

- Dennett, Daniel (1987). The Intentional Stance. Bradford books.

- de Sousa, Ronald (1974). The Good and the True. Mind, 83(332), 534–551.

- Döring, Sabine (2003). Explaining Action by Emotion. The Philosophical Quarterly, 53(211), 214–230.

- Ewing, Alfred (1947). The Definition of Good. Routledge and Kegan Paul

- Fernández, Jordi (2007). Desire and Self-Knowledge. The Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 85(4), 517–536.

- Firestone Chaz and Brian J. Scholl (2016). Cognition Does Not Affect Perception: Evaluating the Evidence for “Top-Down” Effects. Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 39, 1–77.

- Fogal, Dan (2018). The Primacy of Rational Pressure. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Gregory, Alex (2013). The Guise of Reasons. American Philosophical Quarterly, 50(1), 63–72.

- Gregory, Alex (2017a). Are All Normative Judgements Desire-like? The Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, 12(1), 29–55.

- Gregory, Alex (2017b). How Verbal Reports of Desire May Mislead. Thought, 6(4), 241–249.

- Gregory, Alex (2017c). Might Desires Be Beliefs about Normative Reasons For Action? In Julien Deonna and Federico Lauria (Eds.), The Nature of Desire (201–217). Oxford University Press.

- Harcourt, Edward (2004). Instrumental Desires, Instrumental Rationality. Proceedings of The Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume, 78(1), 111–129.

- Hedden, Brian (2015). Reasons without Persons: Rationality, Identity, and Time. Oxford University Press.

- Helm, Bennett (2015). Emotions and Recalcitrance: Reevaluating the Perceptual Model. Dialectica, 69(4), 417–433.

- Huemer, Michael (2005). Moral Intuitionism. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Huemer, Michael (2007). Compassionate Phenomenal Conservativism. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 74(1), 30–55.

- Humberstone, Lloyd (1987). Wanting as Believing. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 17(1), 49–62.

- Johnson. Mark (2001). The Authority of Affect. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 63(1), 181–214.

- Kiesewetter, Benjamin (2017). The Normativity of Rationality. Oxford University Press

- Kolodny, Niko (2005). Why Be Rational? Mind, 114(455), 509–563.

- Korsgaard, Christine (2009) Self-Constitution. Oxford University Press

- Lewis, David (1988). Desire as Belief. Mind, 97(387), 323–332.

- Lewis, David (1996). Desire as Belief II. Mind, 105(418), 303–313.

- Little, Margaret (1997). Virtue as Knowledge: Objections from the Philosophy of Mind. Noûs, 311(1), 59–79.

- McDowell, John (1994). Mind and World. Harvard University Press.

- McDowell, John (1998). Are Moral Requirements Hypothetical Imperatives? In Mind, Value, and Reality (77–94). Harvard.

- McNaughton, David (1988). Moral Vision: An Introduction to Ethics. Blackwell

- Moran, Richard (2001). Authority and Estrangement: An Essay on Self-Knowledge. Princeton University Press.

- Moss, Jessica (2012). Aristotle on the Apparent Good. Oxford University Press

- Oddie, Graham (2005). Value, Reality, and Desire. Oxford University Press.

- Parfit, Derek (2011). On What Matters (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

- Price, Huw (1989). Defending Desire As Belief. Mind, 98(389), 119–127.

- Quinn, Warren (1995). Putting Rationality in its Place. In Rosalind Hursthouse, Gavin Lawrence and Warren Quinn (Eds.), Virtues and Reasons: Philippa Foot and Moral Theory (181–208). Oxford University Press.

- Raz, Joseph (1999). Agency, Reason, and the Good. In Engaging Reason; On the Theory of Value and Action (22–45). Oxford University Press.

- Raz, Joseph (2010). On the Guise of The Good. In Sergio Tenenbaum (Ed.), Desire, Practical Reason, and the Good (111–137). Oxford University Press.

- Scanlon, Tim (1998). What We Owe to Each Other. Harvard University Press.

- Scanlon, Tim (2007). Structural Irrationality. In Geoffrey Brennan, Robert Goodin, Michael Smith, and Frank Jackson (Eds.), Common Minds. Themes from the Philosophy of Philip Pettit (84–103). Oxford University Press.

- Schafer, Karl (2013). Perception and the Rational Force of Desire. The Journal of Philosophy, 110(5), 258–281.

- Schroeder, Mark (2008). Having Reasons. Philosophical Studies, 139(1), 57–71.

- Schroeder, Mark (2009). Means-End Coherence, Stringency, and Subjective Reasons. Philosophical Studies, 143(2), 223–248.

- Schueler, George F. (1995). Desire. MIT Press.

- Setiya, Kieran (2007). Reasons without Rationalism. Princeton University Press.

- Sinhababu, Neil (2011). The Humean Theory of Practical Irrationality. Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, 6(1), 1–13.

- Smith, Michael (1987). The Humean Theory of Motivation. Mind, 96(381), 36–61.

- Smith, Michael (1994). The Moral Problem. Blackwell

- Stalnaker, Robert (1987). Inquiry. MIT Press.

- Stampe, Denis (1987). The Authority of Desire. Philosophical Review, 96(3), 335–381.

- Stefánsson, H. Orri (2014). Desires, Beliefs and Conditional Desirability. Synthese, 191(16), 4019–4035.

- Stocker, Michael (1979). Desiring the Bad: An Essay in Moral Psychology. Journal of Philosophy, 76(12), 738–753.

- Suikkanen, Jussi (in press). Judgment Internalism: An Argument from Self-Knowledge. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 21(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-018-9923-5

- Swartzer, Steven (2015). Humean Externalism and the Argument from Depression. Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.26556/jesp.v9i2.88

- Tenenbaum, Sergio (2007). Appearances of the Good. Cambridge University Press.

- Tenenbaum, Sergio (2008). Appearing good: A Reply to Schroeder. Social Theory and Practice, 34(1), 131–138.

- Velleman, David (1992). The Guise of the Good. Noûs, 26, 3–26.

- Williams, Bernard (1973). Ethical Consistency (166–186). In Problems of the Self. Cambridge University Press.

Notes

Some endorse a version of presentationalism not about desire, but instead about emotion (e.g., Döring 2003). My concern here is purely with presentationalism about desire.

Perhaps this needs some qualification so that, for example, the desire in question is strong enough to be worth thinking about in this context (cf. Harcourt 2004). But this and other qualifications will leave intact the basic thought that there are some rational requirements to form instrumental desires.

For responses to the objection from direction of fit, see Gregory (2017c: 203-205), Little (1997: 63–64), Price (1989: 120–121). For relevant claims about the objection from children and animals, see Campbell (2018: 1156–1157), Gregory (2017c: 210–212), Korsgaard (2009: 110–112), McDowell (1994: 114–124). For responses to the objection from perverse desire, see Alvarez (2010: 218–219), Anscombe (1963: 75), Gregory (2013). For responses to the objection from irrationality in desire, see Bramble (in press), Campbell (2018: 1150–1153), Gregory (2017b; 2017c: 207–210). For responses to Lewis’s objection regarding decision theory, see Bradley and List (2008), Bradley and Stefánsson (2016), Hedden (2015: 156–162), Stefánsson (2014), Price (1989).

If we think that agents can desire things that they believe to be beyond their control, this needs to be qualified with “if you can”. Alternatively, we might think that such states are wishes rather than desires, and so ignore the qualifier (cf. Gregory 2013: 69–70; Velleman 1992: 12–17). Either way, this issue does not materially affect the discussion that follows.

More generally, how should defenders of desire-as-belief understand the strength of desire? The most obvious option is to do so in terms of the strengths of the reasons the agent believes they have. Overall-desire-as-belief is a natural implication of that view, insofar as what you ought to do is what you have most reason to do. Of course, believing that a reason has a certain strength might have further effects on what you are motivated to do, on where you direct your attention, and so on. But on this view these things are (normal) effects of the strengths of your desires, and not constitutive of those desire strengths. I plan to expand on these claims in other work.