Failing to Treat Persons as Individuals

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

If someone says, “You’ve stereotyped me,” we hear the statement as an accusation. One way to interpret the accusation is as follows: you haven’t seen or treated me as an individual. In this essay, I interpret and evaluate a theory of wrongful stereotyping inspired by this thought, which I call the failure-to-individualize theory of wrongful stereotyping. According to this theory, stereotyping is wrong if and only if it involves failing to treat persons as individuals. I argue that the theory—however one interprets it—is inadequate. Either the theory will not reliably identify all cases of wrongful stereotyping or it will fail to adequately explain why they are wrong. I conclude that it does not follow that we must entirely jettison the objection that stereotyping fails to treat persons as individuals. What follows is only that the objection must play a more circumscribed role in a theory of when and why stereotyping is wrong.

1. Introduction

For five days in the spring of 1965, the Janus Society of Philadelphia distributed leaflets outside Dewey’s lunch counter, a hamburger joint that had become a social hub for rowdy, queer youth. Management told employees not to serve the troublemakers. Employees interpreted the directive to mean: don’t serve anyone who looks queer. Gay, lesbian, transgender, and gender non-conforming patrons argued that the new policy was discriminatory. A sit in was organized. Over one hundred and fifty people showed up, and three teenagers were arrested for disorderly conduct. For the next week, the protest continued. Over fifteen hundred flyers were distributed in front of Dewey’s. The flyers explained why, according to one of the country’s earliest gay rights groups, it was unjust to refuse public accommodations to LGBTQ people. “The Janus Society is concerned,” the pamphlet says, “with the worth of an individual and the manner in which she or he comports himself.” The implication was this. By refusing to serve anyone who looked queer, Dewey’s employees were failing to treat LGBTQ people as individuals.

This essay is devoted to the objection that stereotyping fails to treat persons as individuals. Though some readers might be skeptical that the Janus Society’s objection is best construed in this way, I want to take the possibility seriously. In Section 2, I discuss four interpretations of the objection, and I argue that only two of them cohere with the Janus Society’s complaint. In Section 3, I ask whether either version of the objection could constitute the basis for a philosophically viable theory of wrongful stereotyping. In Sections 4–5, I argue that the answer is no. My analysis here underscores a serious problem for any theorist hoping to explain what’s wrong with stereotyping by appealing to the claim that it fails to treat persons as individuals, which I call the problem of absurdity. Two new interpretations of the principle of treating persons as individuals—advanced by Benjamin Eidelson and Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen, respectively—overcome the problem of absurdity. However, as I show in Sections 7–8, neither constitutes the basis for a successful theory of ethically wrongful stereotyping. I end by arguing that it does not follow we must entirely jettison the objection that stereotyping fails to treat persons as individuals. What follows is only that the objection must play a more circumscribed role in a theory of when and why stereotyping is wrong.

2. A Familiar Objection

The objection at the center of this essay is likely to be familiar to readers. It is commonly assumed that we ought to treat persons as individuals and that failing to do so is morally problematic. Philosopher Lawrence Blum even suggests the following: “being seen as an individual is an important form of acknowledgment of persons, failure of such acknowledgment is a moral fault and constitutes a bad of all stereotyping” (2004: 282).

Despite its familiarity, the objection in question is disarmingly slippery. What does the failure to treat someone as an individual consist in, specifically? In this section, I canvas four possibilities.

2.1. Responding to Individuals Based on False or Inaccurate Group Generalizations

Consider the following assertion, made by psychologist Valerie Braithwaite:

In the case of stereotyping, the core issue is inaccurate labeling because group homogeneity is assumed and individuality is not taken into account … imperfect knowledge renders the individual invisible. (2002: 317)

Braithwaite’s idea could be this. When people stereotype, they deploy false or inaccurate views of groups, according to which all members of a group are the same.

In the Janus Society’s statement, one does not find this understanding of failing to treat persons as individuals. The flyer does not say that employees used false or inaccurate generalizations to judge who was queer or who was a troublemaker. Imagine it were true that Dewey’s young, queer patrons were generally rowdier and were, in fact, scaring away a more staid, heterosexual clientele. Even so, the charge stated in the flyer would still stand. The Janus Society asks Dewey’s to adopt a policy according to which individuals are refused service if and only if their actual behavior, in fact, warrants it.

This lack of coherence between the flyer and Braithwaite’s claim is telling. People don’t always perceive groups as absolutely homogeneous when they stereotype. More often than not, stereotypes take the form of generics. “Women are empathetic” and “Doctors wear white coats” are examples. Generic statements lack quantifiers like “some,” “most,” or “all,” and they do not make claims about specific individuals. Linguists and philosophers of language disagree about how to understand the meaning of generic claims. However, everyone agrees that they are not to be understood as universal claims about groups.

What exactly do generic claims mean? Some prominent theorists of generics are pluralists. Sarah-Jane Leslie, for example, divides generics into main three types: majority generics, characteristic generics, and striking-property generics. Each type of generic, on her view, has special truth conditions (2007; 2017). In other work, she argues that generics can be normative in nature as well (Wodak, Leslie, & Rhodes 2015). Other theorists carve up the domain of generics differently. Ariel Cohen, for example, argues that generics are of two types: absolute and relative (1999: 55). Absolute generics, on his view, are true if and only if fifty percent or more of group members have the property in question. Relative generics are true if and only if group members possess the relevant trait at a rate higher than average non-group members. Yet other theorists argue that there is only one set of truth conditions that apply to all generics. A common claim here is that generics are true if and only if “normal” group members in “normal circumstances” possess the ascribed property (Pelletier & Asher 1997; Thompson 2004).

The complexity of generics has implications for how we evaluate people who stereotype in speech, reasoning, and policymaking. First of all, one can’t assume that everyone means the same thing when they stereotype. If I assert, “queer youth are rowdy,” for example, I might be making a claim about typical or normal LGBTQ youth; or I might be advancing a statistical claim, for example, most LGBTQ youth are rowdy; or I could be saying that “real” or “good” queer youth are rowdy. Second, we will often not have decisive evidence that stereotypes are true or false, warranted or unwarranted. For example, if a manager at Dewey’s believed that queer youth were rowdy, he might appeal to personal experience as evidence that the belief is true. But one may wonder. Is his sample size sufficient? Is it representative of the population? Is he merely calling up examples consistent with the stereotype and ignoring other cases? Third, if stereotypes take the form of generics, they will sometimes be accurate or true. People who use stereotypes will thus not always have false or inaccurate beliefs.

Think about the following stereotype: “women are empathetic.” When women are raised to value empathy and actually tend to self-describe as empathic, when they tend to fill social roles where empathy is required or beneficial, when the social benefits of displaying empathy disproportionately go to women, women as a group will have a greater disposition for empathy than men and one that is stable over time (Klein & Hodges 2001; Ickes 2003).

All this is to say: Braithwaite’s apparent understanding of the conditions under which people fail to treat others as individuals is too limited. One could fail to treat someone as an individual even if one were using a true, warranted group generalization. For example, one could fail to treat a woman as an individual by stereotyping her as empathetic, even if it is true that most or typical women have that property. Likewise, one could fail to treat a LGBTQ teenager as an individual by stereotyping her as a rule-breaker, even if it were true that most LGBTQ teens rebel against socially imposed rules, including gender norms. Similarly, you could fail to treat someone as an individual by stereotyping, even if you are well aware that the group to which they belong is not homogeneous. “I’m merely using a heuristic,” you might think. Or, “this person seems to fit the stereotype, though many group members will not.”

Readers might object: I’ve misinterpreted Braithwaite. She says that “inaccurate labeling” is the problem with stereotyping. However, it could be that the relevant inaccuracy lies not in the stereotype itself, but in the epistemic results of stereotyping. The epistemic results of stereotyping include beliefs, predictions, first impressions, and expectations regarding individuals. Perhaps these are false or inaccurate.

This interpretation is no better than the first. People who stereotype will not always end up inaccurately labeling individuals. If one is in fact using a reliable heuristic, the labels applied to people, for example, “troublemaker” or “empathetic” as a result of stereotyping could be correct or accurate in many cases. Even so, the people who are stereotyped would still be entitled to complain that they have been not been treated as individuals. Hence inaccuracy cannot be the core problem of stereotyping.

2.2. Responding to Individuals Based on Group Membership

The problem with stereotyping might be reframed as follows: stereotyping involves judging individuals based on real or apparent group membership.

Consider the employees at Dewey’s. Let’s say they reasoned as follows:

- LGBTQ youth are troublemakers.

- This person is/is likely to be LGBTQ.

- This person is/is likely to be a troublemaker.

What has gone wrong here? The problem, you might think, lies in how stereotypic reasoning works and the kind of evidence we use when we stereotype. When people stereotype, they prioritize “category-level” information. Category-level information is generic in nature. If you judge individuals by generic information, you ignore or discount other potential sources of information. From an epistemic point of view, what matters is that individuals are—or appear to be—members of particular groups. But, the objection goes, an even more reliable and fairer approach would be to judge individuals based on facts about them, specifically. The idea here echoes Martin Luther King’s injunction to judge persons “not by the color of their skin but on the content of their character” (1963).

If you look at the Janus Society flyer, one finds claims in this exact ballpark. “The Janus Society,” the pamphlet states, “is concerned with the worth of an individual and the manner in which she or he comports himself.” The purported problem with the discriminatory policy is, in other words, that it is not sufficiently individualized. Why? Because the policy as interpreted by employees is motivated by a generalization: queer youth are troublemakers. Even if this stereotype were true because queer clientele were statistically more likely to commit expulsion-worthy offenses and even if applying it to individuals led to accurate predictions in the majority of cases, the Janus Society suggests, the policy of refusing service to anyone who looks LGBTQ would be wrong. You should judge individuals by how they actually behave. If someone actually behaves in a way that warrants expulsion, throw that person out. Otherwise, don’t.

Here, then, we find the first fitting interpretation of what it means to fail to treat persons as individuals. You fail to treat persons as individuals, according to this view, if you judge them by group membership.

2.3. Treating Someone as a Number

There is yet a third way to think about what it means to fail to treat someone as an individual. This third interpretation is highlighted by the following recollection, offered by Miné Okubo, a survivor of WWII Japanese internment camps in the United States. In her memoir, Okubo describes registering for the camps in 1942. She writes,

As a result of the interview, my family name was reduced to No. 13660. I was given several tags bearing the family number, and was then dismissed. At another desk, I made the necessary arrangements to have my household property stored by the government …. Our destination was Tanforan Assembly Center, which was at the Tanforan Race Track in San Bruno, a few miles south of San Francisco. (Okubo 1946: 19–20)

Okubo was citizen 13360. Reducing someone to a number is a way of failing to treat that person as an individual.

In the Janus Society flyer, one does not find this complaint. Moreover, it’s hard to see how the complaint could gain traction. Dewey’s employees did not assign queer clients numbers, like the U.S. government assigned numbers to families of Japanese heritage. For this reason alone, I would be disposed to set aside this interpretation of the objection.

But there is something else, as well. Fairness can require treating persons as numbers. I treat my undergraduate students as numbers when I use anonymous grading programs that reduce them to labels like “Student 61” or “Student 4.” Crowded delis treat customers as numbers when they require people to take numerical tickets as a way to enforce the first-come-first-serve rule. Therefore, one cannot explain what’s wrong with stereotyping simply by appealing to the idea that it involves treating persons as numbers. Treating persons as numbers is not inherently wrong. It is only sometimes wrong, and one must dig deeper in order to know what makes cases like the one described by Okubo normatively bad.

2.4. Treating Someone as a Token of a Type

One strategy for investigating the question—and for procuring a more a widely applicable view of failing to treat persons as individuals—is to consider the idea of treating someone as a token of a type. Like treating someone as a number, treating someone as a token of a type implies a kind of depersonalization. However, tokenizing someone is a more general idea, and it fits the phenomenon of stereotyping better.

What exactly does it mean to treat someone as a token of a type? Several possibilities present themselves:

- If you categorize an individual as a member of a social kind, you treat that person as a token of a type.

- If you care about only one aspect of an individual’s social identity to the exclusion of others, you treat that person as a token of a type.

- If you pay attention to only one aspect of an individual’s identity to the exclusion of others, you treat that person as a token of a type.

- If you conceptualize an individual as a generic type whose specific identity does not matter, you treat that person as a token of a type.[2]

Interpretation A does not match the Janus Society’s analysis of Dewey’s policy. Its flyer did not admonish Dewey’s employees simply for categorizing people as queer based on looks. The objection was closer to this: Dewey’s policy had the effect of making individuals’ queer identity the dominant thing that mattered from the point of view of employees. The youth were seen and treated as non-conformist troublemakers and nothing more. Moreover, their failure to conform to gender norms was stigmatized. “The masculine woman and the feminine man,” the flyer says, “are looked down upon.” Accordingly, the Janus Society encouraged Dewey’s staff to look beyond the stereotypes.

Looking beyond stereotypes would require avoiding B–D. That is, it would have required employees to conceptualize queer clients in a fuller way, in part, by paying attention to and caring about facts about them beyond mere group identity. Because the token of a type interpretation nicely fits the case, we can tentatively move forward with it.

3. Working Towards a Theory of Wrongful Stereotyping

Only two of the four initial conceptions of failing to treat persons as individuals cohere with the Janus Society’s objection. In the next two sections, I investigate these two conceptions further. The question is this: could either serve as the basis for a theory of when and why stereotyping is ethically wrong?

In pursuing this question, I will use a non-moralized conception of stereotyping, that is, a conception that does not build wrongness into the very definition of stereotyping. To stereotype someone, I will presume, is to judge that person by real or apparent group membership.[3] My intention in specifying the phenomenon in this way is to offer a conception consistent with social psychology, as well as an inclusive conception with the capacity to identify many different cases as stereotyping.

Two distinctive theories of wrongful stereotyping are suggested by the analysis so far:

Interpretation 1: Judged by Group Membership

| The judged-by-group-membership conception: X fails to treat Y as an individual if and only if X judges Y by group membership. |

| Failure-to-individualize theory of wrongful stereotyping: stereotyping is wrong if and only if it involves judging individuals by group membership. |

Interpretation 2: Tokenizing

| Tokenizing conception: X fails to treat Y as an individual if and only if X treats Y as a token of a type. |

| Failure-to-individualize theory of wrongful stereotyping: stereotyping is wrong if and only if it involves treating individuals as tokens of a type. |

When evaluating these two theories, two desiderata are relevant:

- The identification condition: a successful theory of wrongful stereotyping must be able to identify cases of wrongful stereotyping as such.

- The explanatory condition: a successful theory of wrongful stereotyping must be able to adequately explain why wrongful cases of stereotyping are wrong.[4]

Both versions of the theory mentioned above are off to an equally good start with respect to the identification condition. Both classify stereotyping as ethically wrongful in the Dewey’s case. However a theory that satisfies (1) must do more than get one case right. It must identify a feature that allows us to survey the whole range of cases in which people judge others by group membership and, then, select from this group the subset of cases in which stereotyping is wrong. We cannot yet be sure that either theory does this.

Secondly, a successful theory must be able to adequately explain why cases of wrongful stereotyping are wrongful. We cannot yet be sure that our theory offers adequate explanations in all—or even most—cases.

4. Treating Individuals as Tokens of a Type

Start by considering the tokenizing version of the theory. It says that stereotyping is wrong if and only if it involves treating individuals as tokens of types.

To see the problem with this theory, consider a case which I call Help. In this case, a five-year old child loses her mother in a crowded grocery store. The child sees someone wearing an official-looking uniform. She classifies this person as an employee and expects that the person will be eager to help her. Notice that the child has engaged in stereotyping, according to the definition of stereotyping on offer. She forms an expectation about—hence judges—someone based on real or apparent group membership. The uniformed person might work somewhere else and simply be shopping for groceries on a lunch break. Or the person might actually be an employee of the grocery store.

The question is this: has she engaged in wrongful stereotyping? If we accept the tokenizing theory articulated above, the answer is yes. The girl categorizes an unfamiliar individual as a grocery store employee based on looks. She cares about and pays attention exclusively to that aspect of the person’s identity. She also conceptualizes this person as a generic employee: any employee would have done equally as well. Therefore, she wrongfully stereotypes someone, according to the theory in question.

This result is problematic. The child’s expectation was not motivated by ethically bad prejudice. No one was harmed. Moreover, her view of the person was not disrespectful nor did it entrench oppressive social relationships. The girl was using a uniform as a heuristic, nothing more. Because none of these objections apply, it is hard to believe that the five-year old did something ethically bad.

The unbelievable results continue. Consider these examples:

- A Kantian perceives an unfamiliar individual as a rational being whose autonomy must be respected.

- A Buddhist perceives an unfamiliar individual as a sentient being, whose natural state is suffering.

If seeing persons as tokens of types were intrinsically wrong, the people just described would be doing something ethically wrong by perceiving individuals as tokens of types. Moreover, even in formulating the sentence using the locution “a Kantian” or “a Buddhist,” I would have done something ethically wrongful because I am conceptualizing individuals as generic types and am focusing on only one aspect of their identity to the exclusion of others. These implications reduce the theory in question to absurdity. Just as it is not intrinsically wrong to treat persons as numbers, it is not intrinsically wrong to treat individuals as tokens of a type.[5]

In light of this result, the tokenizing version of the theory could be revised. Maybe treating persons as tokens of a type is not intrinsically wrong, but treating them merely as tokens of a type is. The claim here would be analogous to a familiar Kantian idea. According to Kant’s principle of humanity, it’s not wrong to use persons as means; however, it is intrinsically wrong to treat them merely as means.

The challenge would then be to specify what differentiates treating persons as tokens from treating them merely as tokens. One promising strategy appeals to what I call “diachronic stubbornness” (Beeghly 2015: 9–10). A disposition or view is diachronically stubborn if it is incapable of or resists change over time. In contrast, a disposition or view is diachronically open if it is readily capable of changing over time.

All the earlier views of treating persons as tokens of types (A–D) could be revised to incorporate this idea. Consider the original statement of B: if you care about only one aspect of an individual’s social identity to the exclusion of others, you treat that person as a token of a type. B could be modified as follows: if you care about only one aspect of an individual’s social identity to the exclusion of others and that disposition to care is diachronically stubborn, you treat that person merely as a token of a type.

Here is how the modification works in practice. In Help, we saw a child who cared solely about one aspect of someone’s identity. Yet this same child could be open to thinking and caring about the person in a broader way, especially if given opportunities for further interaction. If she were open in the relevant way, she would not be treating the uniform-wearing person merely as a token of a type. Hence she would not have engaged in wrongful stereotyping, according to the revised theory.

With the revised theory in hand, we can now return the main question of this section: could a tokenizing theory of wrongful stereotyping satisfy the desiderata for a plausible theory of wrongful stereotyping? The answer to this question is still no. To satisfy the identification condition, a theory must be able to reliably identify cases of wrongful stereotyping. With the original tokenizing theory, the problem was over-inclusiveness. Morally benign cases of stereotyping like Help were incorrectly classified as wrongful. With the new-and-improved version of the theory, the opposite problem emerges.

To see why, return to the Dewey’s case. Suppose that Dewey’s employees would have been open to seeing their queer clients in a fuller and more complex way, if they had the opportunity to interact with them outside a work environment. If so, they would not have been treating queer clients merely as tokens of types. Accordingly, they would have done nothing wrong by stereotyping them as troublemakers in the actual case.

This result is revealing. Perhaps the worst kind of stereotyping always involves people who refuse to change their view of others, no matter what. Nonetheless, epistemic or emotional stubbornness is not necessary for wrongful stereotyping. If you judge someone to be “less than” due to pejorative stereotypes, you have done something ethically problematic. You have done something problematic even if you are potentially open to revising your view or developing a caring disposition towards that person in the future.

Perhaps the lesson is this. A revised tokenizing theory could provide a partial account of wrongful stereotyping. Wrongful stereotyping sometimes involves views, dispositions, and conceptions that are diachronically stubborn. However, a partial theory does not vindicate the claim that stereotyping is wrong if and only if it involves failing to treat persons as individuals.

5. Responding to Individuals Based on Group Membership

Setting aside the tokenizing theory, we find a second theory of wrongful stereotyping waiting. According to it, stereotyping is wrong if and only if it involves judging individuals based on group membership.

Historically, this version of the theory and its analogue theory of wrongful discrimination have received a great deal of critical attention, much of it negative. For example, in “What is Wrongful Discrimination?” Richard Arneson argues that treating persons as individuals is not a moral imperative. He asserts that, “there is nothing morally untoward about responding to individuals on the basis of statistical indicators their broad characteristics suggest” (Arneson 2006: 787). In Profiles, Probabilities, and Stereotypes, Frederick Schauer says something similar. “All human beings … deserve to be treated as individuals and not simply as members of a group,” he muses, “or so the argument goes” (Schauer 2006: 19). “But,” he continues,

although this belief in the wrongfulness of reliance on even statistically sound but non-universal generalizations is widespread, it still may not be correct. Indeed, it may not even be plausible. (Schauer 2006: 19)

In an article on racial profiling, Michael Levin repeats the refrain. “I have been arguing so far,” he says,

as if there is an acceptable principle of individualism, the only question being who has a right to it. There is in fact no such principle. People are and must always be judged by the classes to which they belong, the traits they share with them. (Levin 1992: 23)

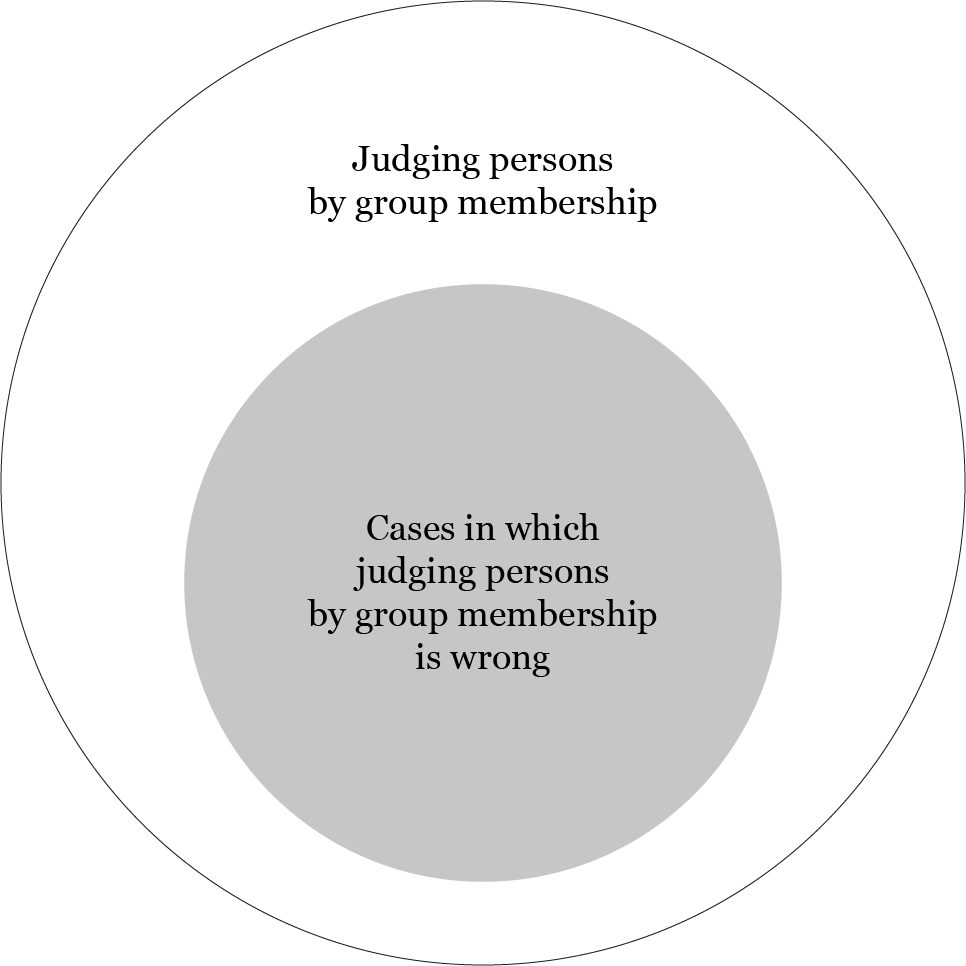

The identification condition partially motivates these objections. To see why, consider the following diagram:

According to the diagram, stereotyping, that is, judging persons by group membership is only sometimes ethically wrong.[6] The diagram clarifies what is seemingly absurd about the theory under investigation. It collapses the above two circles into one, thereby obliterating the distinction between stereotyping and ethically wrongful stereotyping. Call this the problem of absurdity.

The problem of absurdity manifests in numerous cases of misidentification. Any number of cases could be used to argue for the point, including Help. In Help, readers will remember, a five-year old is separated from her mother at a busy grocery store. She forms an expectation about an unfamiliar individual—namely that the person is an employee and is likely to help her—after classifying that person as a store employee. The girl stereotypes this person, that is, makes a judgment based on group membership. According to the theory on offer, she has therefore done something wrong.

Thinking about the explanatory condition reveals what has gone awry. A theory’s explanations cannot be adequate if they rest on a false presumption. In this case, the theory in question rests of the false presumption that judging persons by group membership is in itself intrinsically wrong.

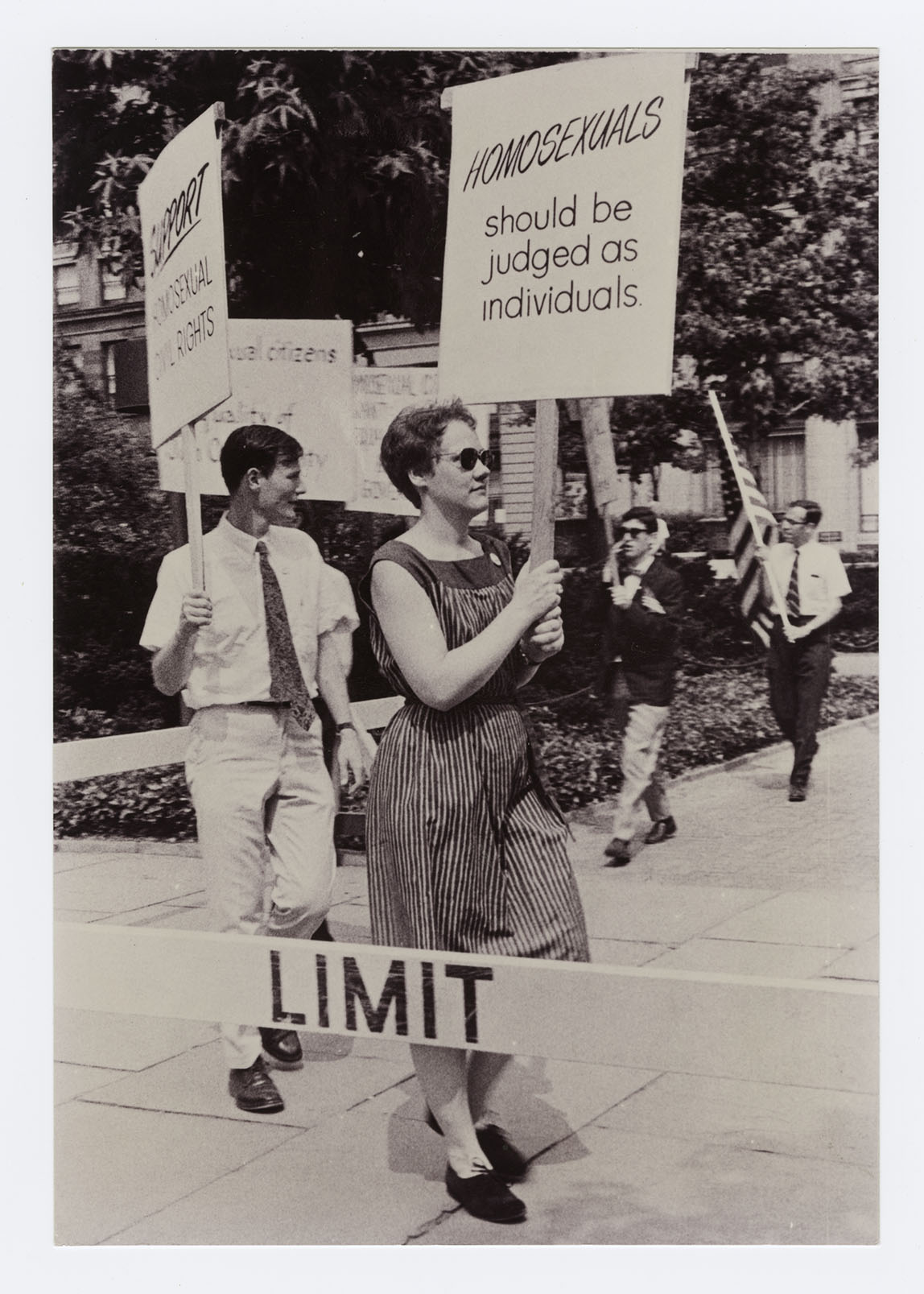

Help suggests that the presumption is dubious, but other cases reveal it even more clearly. Think about one I call Protestor. Imagine that an employee at Dewey’s sees the following person picketing outside of the restaurant.

The employee stereotypes the woman above as a lesbian. On what grounds? The individual appears to be a woman. Add to that her short haircut and the fact that she is protesting in favor of gay rights. She very well could be a lesbian.

It is hard to see what one has done ethically wrong by expecting that the individual pictured above is a lesbian, so long that the unspoken expectation is tentative and open to change with further evidence. The woman—Barbara Gittings—did in fact identify as a lesbian. She was the long-time partner of the photographer who took the picture. Her presence at the protest above was intended as a sign of solidarity. Gittings wanted people to identify her as a lesbian.

A defender of theory under investigation could respond that we must think of acts of stereotyping in a more global way. In crafting my counterexample, I have focused on an apparently innocuous inference. But, what if we panned back? What if we looked at the concept of a lesbian on which the employee was relying? We’d likely see that the concept was ethically compromised. Having been formed in a sexist and homophobic context, it would undoubtedly include ethically objectionable elements, as would the stereotypes associated with the concept. Thus, it is not so odd to think that stereotyping in the case above is problematic. Ethically compromised cognitive resources motivated the expectation.[7]

This response is potentially helpful. If one pans back and looks at the bigger cognitive and social picture, perhaps one can get behind the idea that judging individuals by their real or apparent membership is intrinsically problematic. There is always, the thought goes, something wrong with using compromised cognitive resources and, in a world as unjust as ours, our cognitive resources are always ethically compromised.

On the other hand, imagine a hypothetical situation in which someone has a concept of “lesbian” but that concept does not include ethically problematic elements. Perhaps the world has radically changed, so that sexism, homophobia, and transphobia are things of the past. Suppose that someone raised in this context sees the picture above and believes that the woman featured in it is a lesbian. The person infers that she was a social justice warrior in her time and faced discrimination for being “out.” Such a person would be doing something ethically wrong, according to the theory under investigation.

This implication highlights an important fact. It does not matter whether a person’s concepts are ethically compromised or not, according to the present theory. An act of stereotyping is wrong simply because it involves judging persons by group membership. This claim returns us to the problem of absurdity. There is no reason to think that judging persons by group membership is always intrinsically wrong.

6. Recent Attempts to Answer the Problem of Absurdity: Two New Conceptions of Failing to Treat Persons as Individuals

For some theorists, the upshot is this: we must stop explaining what’s wrong with stereotyping—as well as what’s wrong with discrimination—by saying that it fails to treat persons as individuals. However, other theorists take the analysis so far as a challenge. The challenge is to articulate a new interpretation of failing to treat person as individuals that does not generate the problem of absurdity.

In recent work, both Benjamin Eidelson and Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen have advanced novel views of what it means to fail to treat persons as individuals. Both recognize the seriousness of what I’ve called the problem of absurdity, and both articulate conceptions of failing to treat persons as individuals designed to avoid it.

6.1. The Use All Your Information Conception

In “We are All Different: Statistical Discrimination and the Right to be Treated as an Individual,” Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen offers the following suggestion:

X treats Y as an individual if, and only if, X’s treatment of Y is informed by all relevant information, statistical or non-statistical, reasonably available to X. (2011: 54)

Call this the use all your information conception of treating persons as individuals. According to this conception, we fail to treat others as individuals if and only if our treatment of that person is not informed by all the relevant information reasonably available to us.

Notice that a theory of wrongful stereotyping that deploys the use all your information conception avoids the problem of absurdity. Responding to persons based on their group membership is wrong, according to this new conception, only when a person ignores relevant, reasonably available information. In conditions where individualized information is not relevant or reasonably available, there is nothing wrong with forming one’s judgment about someone on the basis of group membership. Therefore, were we to use this interpretation as the basis for a theory of wrongful stereotyping, we could maintain the distinction between stereotyping and wrongful stereotyping.

6.2. The Respect for Autonomy Conception

In “Treating People as Individuals,” Benjamin Eidelson articulates a second way of interpreting the principle of treating persons as individuals. He writes,

In forming judgments about Y, X treats Y as an individual, if and only if,

(Character Condition) X gives reasonable weight to evidence of the ways Y has exercised her autonomy in giving shape to her life, where this evidence is reasonably available and relevant to the determination at hand.

(Agency Condition) if X’s judgments concern Y’s choices, these judgments are not made in a way that disparages Y’s capacity to make those choices as an autonomous agent. (Eidelson 2016: 216)

Call this the respect for autonomy conception of treating persons as individuals.

The respect for autonomy conception’s character condition mirrors the use all your information conception in one way. Its character condition says: when we judge others, we must give reasonable weight to relevant evidence about individuals’ character, values, and personal history when such evidence is reasonably available. It follows that there is nothing wrong with stereotyping people when personalized information is irrelevant or not reasonably available. So not all stereotyping would violate the character condition.

What about the agency condition? One could argue that stereotyping people always disparages their autonomy. By stereotyping, we act as if people don’t have any choice about how they are or what they do. Interpreted in this way, the agency condition invites the problem of absurdity. It invites the problem because it entails that stereotyping always involves failing to treat persons as individuals, thereby collapsing the distinction between stereotyping and wrongful stereotyping.

To avoid the problem of absurdity, the agency condition must be interpreted more narrowly. Suppose you predict that I will pick up a baby at a party because I am a woman and you believe that women love babies and such love is biologically necessitated. Your way of judging me would violate the agency condition. Even if you were correct that I love babies, you would judge my choices in a way that presumes that I have no say in the matter, thereby disparaging my autonomy. However, suppose you expect that I will pick up a baby based on a generic claim about women: women love babies. This generic claim leaves open the possibility that I will choose not to pick that baby up. Statistical claims are only claims about what is likely to be the case. So you would not be disparaging my capacity for autonomy if you formed an expectation of me based on a stereotype. Likewise, if you thought that I was a defective woman because I don’t pick up the baby, your belief does not entail or presuppose that my choice wasn’t free.

Though I have not yet developed a precise criterion for distinguishing agency-violating cases of stereotyping from cases that do not violate the agency condition, this much is clear. One could articulate the agency condition in a way that does not invite the problem of absurdity. If so, there will be cases of stereotyping in which the people who stereotype treat others as individuals and, hence, do not engage in wrongful stereotyping.

Both new conceptions of treating persons as individuals—the use all your information conception and the respect for autonomy conception—avoid the problem of absurdity. Because they avoid the problem of absurdity, these conceptions might serve as the basis for a viable theory of wrongful stereotyping.

7. Failing to Use All Your Information

Here is how one would articulate the first new version of the theory:

Interpretation 3: Use All Your Information

| The-use-all-your-information conception: X fails to treat Y as an individual if, and only if, X’s treatment of Y is not informed by all relevant information, statistical or non-statistical, reasonably available to X. |

| Failure-to-individualize theory of wrongful stereotyping: stereotyping is wrong if and only if it involves treating someone in a way that is not informed by all relevant, reasonably available information. |

To test this version of the theory, return to the Dewey’s case. Imagine that an unfamiliar teen enters Dewey’s on the day of the protest. Behind the counter, an employee sizes up the teen. He has never seen this person before. The employee perceives the kid as a type: “one of the gays.” Immediately he stereotypes him as the kind of person who engages in raucous, disruptive behavior. Call this case At A Glance. Has the employee done anything ethically wrong by stereotyping the teen, according to the theory under investigation?

On the one hand, the answer seems to be yes. This employee could try to chat up the teen and get a better read on him. He might also observe the teen from a distance, seeing how he behaves at the lunch counter. Such information is relevant to the question of whether or not this person is actually a troublemaker and deserves to be thrown out, and it would take little effort to gather. Moreover, doing so would express concern for “the worth of the individual and the manner in which she or he comports himself,” just as the Janus Society recommends.

On the other hand, information may not be reasonably available. Sure, the employee could chat up the teen or let him loiter in defiance of the policy. However, failure to comply with store policy could result in being fired. For some employees, getting fired could be financially devastating. The more vulnerable the employee, the more “expensive” it would be to gather information in the ways that directly contravened store rules.

The problem here generalizes. Reasonable availability is a practical notion. Whether or not information is reasonably available depends on how easy it is to access and the costs involved in getting it. In an unjust world, gathering information about others can put our lives and livelihoods at risk. Likewise, practical constraints bear down on us. Sometimes we see people from a distance and couldn’t talk to them to figure out who they are, even if we wanted to. Moreover, people in the grip of ideologies may be incapable of accessing relevant information due to their warped vision.

The theory’s implications thus get even worse. Think about a case that I call Bigot. A man is riding a bus past Dewey’s. He sees the store thronged with queer protestors. He silently thinks to himself, “Degenerate pedophiles.” Obviously, he is judging protestors on the basis of stigmatizing stereotypes, and there is something ethically wrong with stereotyping queer protestors in this way. Yet the present theory doesn’t necessarily identify the man’s stereotyping as wrongful. The bigot wrongfully stereotypes, according to the theory, if and only if he ignores relevant information, which was reasonably available to him. Ironically, the more we describe this person as deep in the grip of sexist, homophobic, and transphobic ideologies, the more sheltered his life is, the less able he is to exit the bus due to practical constraints, the stronger case we have for thinking that he treated the protestors as individuals.

Some readers might object that the bigot must have had reasonable access to information challenging his stereotypic presumptions. Feminist and critical race theorists have long argued that ignorance is an expression of agency, after all.[8] Perhaps the typical bigot could thus be faulted for failing to use relevant, reasonably available information.

This line of response has its limits. One can gerrymander the example such that relevant information about queer people was not reasonably available to the bigot, given his history and social position. Perhaps he was intensely indoctrinated. Raised in a cultish setting, he was taught that gay people were degenerate pedophiles. Outside information was intentionally limited within the community. Now an adult, the bigot rides the bus to and from work every day. He remains psychologically and emotionally incapable of stepping outside of his sect’s fundamental beliefs. More details could be piled on. Pile on as many as you like. My view would be the same. He engages in wrongful stereotyping, even if he couldn’t have realized that his stereotypes were false, as well as morally repugnant.

One could respond to the argument above by going down a rabbit hole. The thought is this: I must have made some mistake in how I’ve interpreted the terms “informed by,” “reasonably available” or “relevant.”[9] Perhaps one could play around with different interpretations, until we find a version of the theory that satisfies the identification condition and classifies stereotyping in cases like Bigot as wrongful.

I agree that getting clearer on these terms would be a good thing. But I am not going down that rabbit hole, and here is why. It is a waste of time, given my purposes. Even if a theory of wrongful stereotyping based on the use all your information conception could satisfy the identification condition (which I doubt), it would never satisfy the explanatory condition.

Remember what the use all your information conception says:

X treats Y as an individual if, and only if, X’s treatment of Y is informed by all relevant information, statistical or non-statistical, reasonably available to X. (Lippert-Rasmussen 2011: 54)

This principle could never provide an adequate explanation of when and why stereotyping is ethically wrong.

To see this, suppose that “X” is Fatima and “Y” is a cup in her cupboard. If Fatima’s judgment about the cup in her cupboard is not informed by all the relevant information, reasonably available to her, she is failing to treat the cup as an individual. However, it is not obvious that she has done anything ethically wrong. Indeed, I would argue that it is highly implausible that she has done anything wrong from an ethical point of view. If we switch our example so that “Y” is now a human being, one may think that Fatima has done something ethically wrong if she fails to treat a human being as an individual. But the use all your information theory of wrongful stereotyping does not explain why.

To explain why there is an ethical imperative to judge persons (but not cups) as individuals, we’d need to look outside the use all your information conception. For example, one could appeal to the ideal of respect for persons and argue that respect for persons sometimes or always requires that we judge individuals using all relevant information reasonably available to us. The work of ground breaking feminist philosophers like Iris Murdoch (1970) and Lorraine Code (1987) could come in handy here, as well as more recent feminist work on moral encroachment (Basu 2017).

If the theory in question requires supplementation, its explanatory inadequacy is manifest. On its own, the use all your information theory is incapable of explaining what’s ethically wrong with stereotyping.[10] Adequate explanations emerge only when such a theory is connected to a background theory about why and when our epistemic treatment of others matters, ethically. To get an adequate theory of wrongful stereotyping, one must look outside the idea of treating persons as individuals and towards more fundamental ethical values.

8. Respect for Autonomy

One more version of the theory remains:

Interpretation 4: Respect for Autonomy

| The respect-for-autonomy conception: in forming a judgment about someone, X fails to treat Y as an individual if (violation of character condition) X does not give reasonable weight to evidence of the ways Y has exercised her autonomy in giving shape to her life, where this evidence is reasonably available and relevant to the determination at hand or (violation of agency condition) if X’s judgments concern Y’s choices, these judgments are made in a way that disparages Y’s capacity to make those choices as an autonomous agent. |

| Failure-to-individualize theory of wrongful stereotyping: stereotyping is wrong if and only if it violates either the character condition or agency condition (see above). |

This new theory will not work either. It too violates the identification condition. The character condition says: when judging someone, you must give reasonable weight to evidence of the ways that person has shaped her life through autonomous choice when such evidence is reasonably available and relevant to the determination at hand. The “reasonably available” qualification is necessary to avoid the problem of absurdity. Yet it limits the theory. People who engage in ethically wrongful stereotyping do not always have reasonable access to evidence of the ways in which individuals shape their lives through autonomous choice.

Once again, Bigot offers a case in point. Whizzing by on a bus, this man cannot stop to gather evidence about the specific ways in which the protestors have exercised autonomy throughout the course of their lives. Even if he could exit the bus, gathering the relevant evidence could be prohibitively costly. Specify the practical stakes however you like. Perhaps he is taking the bus to the hospital and will suffer a heart attack and die if he gets off. Perhaps he will be fired from his job if he exits. Likewise, the protestors themselves might block the bigot’s access to personalized information. I, for one, would not share information about myself with a potentially hostile stranger. So long as the bigot lacks reasonable access to relevant information, he satisfies the character condition.

Next consider the agency condition. Does the bigot disparage individuals’ agency by stereotyping them as degenerates? If we interpret the agency condition narrowly, as I have argued we must, the answer may be no. Many people who share the bigot’s attitudes believe that LGBTQ people have chosen to act on “perverted” desires. Such people would say that the protestors are defective by nature (since they have bad desires) and that they have made bad choices (since they have chosen to indulge these desires).[11] Judgments such as these do not disparage anyone’s capacity for agency; rather, they criticize the content of people’s choices.[12]

It follows that the bigot does not necessarily fail to treat protestors as individuals, according to the current theory. Indeed, he could very well succeed in treating persons as individuals, despite stereotyping them.

This result is beyond belief. Bigot is a case around which nearly all other theories of wrongful stereotyping converge. Morally bad prejudice is to blame for the man’s expectations. The bigot’s thoughts are also disrespectful. Moreover, his way of thinking is one that persists, continuing to harm and oppress against LGBTQ individuals to this very day.[13] So we have very good reason to think that the bigot—no matter what kind of information is reasonably available to him and no matter what his views on queer agency—has done something wrong when he stereotypes queer protestors in the way he does.

In response to the theory’s deficiencies, one could return to the respect for autonomy conception and try to tweak it. Maybe there is some way of interpreting—or revising—the character and agency conditions so that they will be more sensitive to injustice, while avoiding the problem of absurdity. Should readers be tempted by this response, I encourage them to pursue it. I myself believe that it is a dead end for reasons explained in the conclusion.

9. Conclusion

I began this essay with a real-life objection. “All too often,” the Janus Society stated in its pamphlet,

there is a tendency to be concerned with the rights of homosexuals as long as they somehow appear to be heterosexual, whatever that is. The masculine woman and the feminine man are looked down upon … but the Janus Society is concerned with the worth of an individual and the manner in which she or he comports himself.

While the pamphlet articulates a familiar objection to stereotyping, I have not been able to vindicate the claim that failing to treat persons as individuals “constitutes a bad of all stereotyping” (Blum 2004: 282).

The biggest take-home point here is negative. The theory I’ve been examining in this essay asserts that stereotyping is wrong if and only if it fails to treat persons as individuals. No version of this theory so far has been successful.

On the other hand, there is a vindicating aspect to my analysis. Some theorists have argued that there is no moral imperative to treat persons as individuals, and that it is absurd to think there is one. However, as I have emphasized, there are conceptions of failing to treat persons as individuals—the use all your information conception and the respect for autonomy conception—that do not devolve into absurdity. Even the token of a type conception can be articulated in a way that avoids the problem of absurdity. If so, there very well could be a moral obligation to sometimes or always treat persons as individuals.

This raises a question. Could the objection that stereotyping fails to treat persons as individuals play a role in the best theory of when and why stereotyping is wrong? The answer is yes. However, my analysis suggests two constraints apply:

- Normative dependence: the force of the objection that stereotyping fails to treat persons as individuals will always depend on other ethical objections to stereotyping.

- Limited scope: the objection that stereotyping fails to treat persons as individuals will not apply in all cases of wrongful stereotyping. It will only ever apply in a subset of wrongful cases.

Think, first, about normative dependence. The hypothesis is this: if you are going to include the wrong of failing to treat persons as individuals in your theory of wrongful stereotyping, you must normatively tether it to something else. Tethering can happen in multiple ways. Consider Eidelson. He integrates elements of a larger ethical framework into the very definition of treating persons as individuals by appealing to Kantian concepts like “autonomy” and “agency.” Then he argues that failing to treat persons as individuals is disrespectful, thereby making the wrong of failing to treat persons as individuals dependent on the wrong of disrespect. His is an explicitly integrative approach. However, a behind the scenes approach is also possible. For example, you could argue that a more fundamental ethical norm requires treating persons as individuals as defined by Lippert-Rasmussen. In this case, ethical demands implicitly lie behind apparently epistemic imperatives. If so, the philosophical challenge is to identify the relevant ethical norms and explain why and when they require us to treat persons as individuals.

Next consider limited scope. The hypothesis is this: if one articulates the objection that stereotyping fails to treat persons as individuals in a way that avoids the problem of absurdity, one cannot use that objection to condemn all wrongful stereotyping. The objection will only work in a subset of cases.

Technically, I’ve left it open that theorists could reinterpret or revise the theories discussed in order to satisfy the identification condition. So perhaps limited scope is better put as a challenge. If you want to claim that stereotyping is wrong if and only if it fails to treat persons as individuals, you have a hard needle to thread. You must provide a conception of treating persons as individuals that avoids absurdity, while correctly identifying all wrongful cases.

I am not optimistic that this challenge can be met—and neither are Eidelson and Lippert-Rasmussen.[14] Moreover, it is not entirely obvious to me why one would want to take on this burden, given the fact that other ethical objections motivate the claim that we must treat persons as individuals.[15]

Returning to the Dewey’s case with these thoughts in mind, interpretative vistas begin to open. It was already clear that Dewey’s discriminatory policy and its employees’ practice of stereotyping queer patrons were ethically wrong. But now we know something new: this treatment could have (but did not necessarily) involve failing to treat queer patrons as individuals. However, even if the objection can be vindicated, it cannot stand on its own normative feet. Deeper ethical objections lie elsewhere, and it is to these objections that one must turn in crafting a theory of wrongful stereotyping.

Acknowledgments

This article has been a long time coming. Many people gave me feedback that improved this paper, including Véronique Munoz-Dardé, Jay Wallace, Michael Martin, Victoria Plaut, Alex Madva, Katie Gasdaglis, Mari Mikkola, Ásta, Resa-Philip Lunau, Marjorie Gelb, Judith Lichtenberg, Jennifer Morton, Leslie Francis, Hilde Lindemann, Cynthia Stark, Elijah Milgram, Deborah Hellman, Susanna Siegel, Nathifa Greene, Jennifer Mueller, Cat Pruiett, Michael Brownstein, Joshua Rivkin, and Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen, as well as two anonymous reviewers at Ergo. The librarians at the National Humanities Center were also gems. Versions of this paper were presented at the Eastern APA, the Intermountain West Graduate Conference, the Bias in Context Conference at Cal Poly Pomona, the Presupposition and Perception NEH Summer Workshop at Cornell University, the Mentoring Workshop for Early Career Women at UMass Amherst, the 6th Meeting on Ethics and Political Philosophy at the University of Minho, and the Legal Theory Workshop at the University of Virginia. I wrote this paper with funding from the American Association for University Women, The National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Humanities Center, the University of Utah, and the Sterling M. McMurrin Endowment.

Bibliography

- Antony, Louise (2016). Bias: Friend or Foe? Reflections on Saulish Skepticism. In Michael Brownstein and Jennifer Saul (Eds.), Implicit Bias & Philosophy: Volume I (157–190). Oxford University Press.

- Arneson, Richard (2006). What is Wrongful Discrimination? San Diego Law Review, 43, 775–1071.

- Basu, Rima (2017). What We Epistemically Owe to Each Other. Manuscript in preparation.

- Beeghly, Erin (2015). What is a Stereotype? What is Stereotyping? Hypatia, 30(3), 675–691.

- Blum, Lawrence (2004). Stereotypes and Stereotyping: A Moral Analysis. Philosophical Papers, 33(3), 251–289.

- Braithwaite, Valerie (2002). Reducing Ageism. In Amy Cuddy and Susan Fiske (Eds.), Ageism: Stereotyping and Prejudice Against Older Persons, (311–337). MIT Press.

- Code, Lorraine (1987). Epistemic Responsibility. Brown University Press by University Press of New England.

- Cohen, Ariel (1999). Think Generic: The Meaning and Use of Generics. University Center for the Study of Language and Information.

- Egan, Andy (2011). Comments on Gendler’s “The Epistemic Costs of Implicit Bias.” Philosophical Studies, 156, 65–79.

- Eidelson, Benjamin (2016). Discrimination and Disrespect. Oxford University Press.

- Fanon, Franz (2008). Black Skin, White Masks (Richard Philcox, Trans.). Grove Press.

- Ickes, William (2003). Everyday Mind Reading: Understanding What Other People Think and Feel. Prometheus.

- Klein, Kristi and Sarah Hodges (2001). Gender Difference, Motivation, and Empathic Accuracy: When It pays to Understand. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 720–730.

- Leslie, Sarah-Jane (2007). Generics and The Structure of the Mind. Philosophical Perspectives, 21, 375–403.

- Leslie, Sarah-Jane (2017). The Original Sin of Cognition: Fear, Prejudice, and Generalization. Journal of Philosophy, 114(8), 393–421.

- Levin, Michael (1992). Responses to Race Differences in Crime. Journal of Social Philosophy, 23(1), 5–29.

- Lippert-Rasmussen, Kasper (2011). ‘We are all Different’: Statistical Discrimination and the Right to Be Treated as an Individual. Journal of Ethics, 15(1), 47–59.

- Lippert-Rasmussen, Kasper (2014). Born Free and Equal: A Philosophical Inquiry Into The Nature of Discrimination. Oxford University Press.

- King, Martin Luther (1963). I Have a Dream. For an audio recording of speech as well as its text, see http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkihaveadream.htm

- Murdoch, Iris (1970). The Sovereignty of the Good. Routledge.

- Okubo, Miné (1946). Citizen 13660. Columbia University Press.

- Pelletier, Jeffrey and Nicholas Asher (1997). Generics and Defaults. In J. van Benthem and A term Meulen (Eds.), Handbook of Logic and Language (1125–1179). MIT Press.

- Schauer, Frederick (2006). Profiles, Probabilities, and Stereotypes. Harvard University Press.

- Stryker, Susan (2008). Transgender History. Perseus Books.

- Sullivan, Shannon and Nancy Tuana (2007). Race and the Epistemologies of Ignorance. State University of New York Press.

- Thompson, Michael (2004). Apprehending Human Form. Modern Moral Philosophy: Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement, 54, 47–74.

- Tribune Media Wire (2016). Baptist Pastor on Orlando Attack: Are You Sad that 50 Pedophiles Were Killed Today? Retrieved from http://wnep.com/2016/06/14/baptist-pastor-on-orlando-attack-are-you-sad-that-50-pedophiles-were-killed-today/

- Wodak, Daniel, Sarah-Jane Leslie, and Marjorie Rhodes (2015). What a Loaded Generalization: Generics and Social Cognition. Philosophy Compass, 10(9), 625–635.

- Young, Iris Marion (1990). Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton University Press.

Notes

Some of these interpretations suggest that treating persons as tokens is the same thing as judging them by group membership. If so, this conception could collapse (at least partially) into the previous one. However, the idea that we should care about people as individuals is distinct from the claim that we should judge persons by facts about them as individuals. So not all understandings of the relevant objection (and corollary moral demand) are collapsible.

I argue for a non-moralized conception of stereotyping elsewhere (2015) and provide a list of other authors who endorse a non-moralized view like mine (including Antony 2016), as well as those who endorse a moralized view of stereotypes and stereotyping (including Blum 2004).

I argue for (and further interpret) these desiderata in my monograph What’s Wrong with Stereotyping, currently under contract with Oxford University Press. See Figure 1, Section 5 for a visual representation of the challenge of crafting a theory of wrongful stereotyping.

Other examples support of this point as well. See, e.g., Fanon (2008: 92). After being stereotyped, Fanon explains to readers, “I quite simply wanted to be considered a man among men.”

If one holds a moralized conception of stereotyping, one will label the diagram differently. Specifically, one will reserve the term “stereotyping” for the smaller circle and call the bigger circle something else. The point that I make here stands, no matter how one uses terminology.

For scholarship on the epistemology of ignorance, see Sullivan and Tuana (2007).

For a view according to which we have “reasonable access” to a great deal of information that seems to escape us in any given moment, see Murdoch (1970).

Notice that this objection applies equally to the token of a type theory. If there is something wrong with seeing or treating persons merely as tokens of a type, that wrong must be specified independently.

This is, roughly, the official position of the Catholic Church. It is also the presupposition behind so-called gay conversion therapy, whereby gay people “learn” to cultivate heterosexual desires and to refrain from acting on their homosexual ones.

After one of the largest mass shootings to date in U.S. history, which occurred at a gay bar in Orlando Florida on June 12, 2016, a Baptist minister celebrated the murders in a sermon to his congregation: “Hey, are you sad that fifty pedophiles were killed today? No … I think it’s great. I think that helps society … ” (Tribune Media Wire 2016). See Iris Marion Young (1990: 61–65). Violence, as Young notes, is one of the five “faces” of oppression.

Lippert-Rasmussen (2014) endorses a harm-focused theory of wrongful discrimination and does not believe that failing to treat persons as individuals is inherently wrong. Eidelson (2016) argues that wrongful discrimination is either harmful or disrespectful. Not all instances of harmful discrimination involve failing to treat persons as individuals, according to him; not even all cases of disrespectful discrimination will have this problem, if he is right. Though neither is focused on stereotyping specifically, their analyses of discrimination generalize.

Moreover, I worry that an excessive focus on this objection is fetishistic. It places all the normative emphasis on how individuals are treated, while ignoring the larger social-structural issues at hand.