Intellectual Humility: An Interpersonal Theory

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In this paper, I will argue in contrast with much of the existing literature, that humility and intellectual humility are interpersonal (as opposed to personal) virtues. Also in contrast with what has been said before, I will further argue that the fruits of intellectual humility are external to the virtue holder. The paper begins with a review of the literature on humility and intellectual humility. I then offer my alternative account, answer some objections, and briefly propose a compromise position to appease those who are sympathetic to traditional conceptions.

1. Introduction

At first glance, humility seems rather peculiar. On the one hand, many religions and cultures consider it foundational for a good life or virtuous character.[1] On the other hand, there is a sense in which humility is importantly different from many other popular moral principles. That is, many if not most widely-shared moral principles are focused on the good of others. Along these lines, moral virtues are character traits that generally concern the virtue holder’s behavior toward others. Generosity, for instance, is about sharing with others, and kindness about treating others with respect. This interpersonal quality, however, is strangely at odds with humility, a virtue often assumed to be all about how agents relate to themselves. Let us consider, for instance, some of the recent philosophical literature. [2] Appealing to Adam Smith, Jason Brennan (2007) has argued that the modest person judges himself according to an ideal and simultaneously judges others by a more plebian standard. Under Brennan’s account, the unique way in which the humble agent judges himself is central to the virtue of modesty. Another much-discussed view is put forth by Julia Driver. Driver (1989) argues that the humble person holds a false self-perception, under evaluating her own worth.[3] Both of the aforementioned views can be put under the umbrella of what I will call “self-assessment accounts”, which have at least two features in common.

Self-Assessment Accounts of Humility:

- (1) The virtue consists of a disposition to hold a certain self-assessment.

- (2) The virtue holder refrains from going overboard in (1).

A main thesis of this paper is that self-assessment accounts of humility are wrong: I propose that humility is a virtue concerning our attitudes and acts directed not toward ourselves but rather toward others. In other words, I will argue that humility and intellectual humility are interpersonal (as opposed to personal) virtues. I will further argue that the fruits of intellectual humility are external to the virtue holder.

My plan for the paper runs as follows: I first review the literature on intellectual humility. Because I disagree with the contemporary literature regarding key features of humility and its intellectual variant, I cannot just use the existing literature to build my own theory, but must instead use it as a point of contrast.[4] After this review I explain my own alternative account. I begin describing the virtue broadly, in terms of what intellectually humility is not. Only then do I move on to the gritty conceptual details. After addressing potential objections, I conclude with an explanation of how intellectual humility betters the world in a uniquely intellectual fashion.

2. Two Varieties of Intellectual Humility

Similar to humility simpliciter, most accounts in the contemporary literature argue that intellectual humility is a virtue of self-assessment.[5] That is, most accounts of intellectual humility describe the virtue as one that involves an agent’s assessment of the self. What distinguishes humility and intellectual humility, is the latter’s self-assessment is not of the self simpliciter but rather of particular aspects of the self. More specifically, according to self-assessment accounts of intellectual humility,

- (1) The virtue consists of a disposition to hold a certain assessment of aspects of the self, most notably, aspects that are specially “intellectual” or “epistemic.”

- (2) The agent who is intellectually humble necessarily refrains from going overboard in (1).

The self-assessment account that will be my primary focus is one put forth by Dennis Whitcomb, Heather Battaly, Jason Baehr, and Daniel Howard‐Snyder. We can call it the “Limitations Owning View.” (I will sometimes refer to the authors collectively as “The Limitations Owning Crew”). Whitcomb et al. describe their account in opposition to various contemporary theorists, including Robert Roberts and Jay Wood. I will closely review Whitcomb et al.’s criticism of Roberts and Wood, for my own account will end up sharing important features with the latter. More specifically, while the absence of vanity is not as central to my account as it is to Roberts and Wood’s, I am in strong agreement with them that a lack of concern for intellectual status is an important trait of the intellectually humble. In their own words,

it is not quite enough to say that the humble person lacks vanity. He does not merely lack it, but veers in the other direction. We have said that vanity is an excessive concern to be well regarded by other people …. Humility, as vanity's opposite, is … a kind of emotional insensitivity to the issues of status. (Roberts & Wood 2003: 259)

Against the above view, The Limitations Owning Crew argues that a lack of concern for intellectual status is neither necessary nor sufficient for humility. They offer the following counterexample, describing a woman who cares about her intellectual status “since she works in a male-dominated profession that marginalizes those without status … and she knows that neither she nor her family will flourish as well as it might if she has a low concern for status” (Whitcomb et al. 2017: 516). This example aims to show that low concern for status is not (contra Roberts and Wood) necessary for intellectual humility. This criticism, however, is misplaced. Roberts and Wood argue that vanity, understood as excessive concern for status, is only opposed to humility if the status is desired for the sake of status itself:

You may desire to make a good appearance so as to make money or get promoted, or as evidence of some excellence in yourself … only insofar as you are concerned to make a good appearance for the positive social status it entails is the concern vanity. (Roberts & Wood 2003: 259, emphasis in original)

The subject of the Limitations Owning Crew’s counterexample does not fit the above requirements for she is concerned about her status for the sake of her and her family’s flourishing, not for the sake of status itself. The example, therefore, bears little relevance to the Roberts and Wood anti-vanity criterion and cannot then speak against its necessity.

Whitcomb et al. also challenge the possibility that a low concern for intellectual status is sufficient for intellectual humility by again offering a counterexample, this time involving the notorious, “Professor P.” Professor P, while having no concern for his intellectual status, nonetheless “constantly references his own strengths, accomplishments, and publications … seizes every opportunity to relate what others say to his own projects and theories … [and] is oblivious to his intellectual limitations” (2017: 516). While I admit that Professor P does not seem intellectually humble, I find this example puzzling, for if such hypothetical professor has no concern for intellectual status, it is unclear why he would constantly reference his own accomplishments. It seems comparable to someone obsessed with accumulating wealth having no concern for material possessions. If such odd individuals exist, I am not sure what they show—perhaps that certain kinds of mental illness can pose problems for what would otherwise seem intuitive conceptual criteria.

I now move on to the positive thesis of the Limitations Owning account, which argues that intellectual humility consists in “owning one’s intellectual limitations.” More specifically, the authors argue that the following dispositional profile defines intellectual humility.

Intellectual Humility (Limitations Owning View): “a dispositional profile including cognitive, behavioral, motivational, and affective responses to an awareness of one’s limitations.” (2017: 518)[6]

While I ultimately disagree with the above account of intellectual humility, I am largely sympathetic to this train of ideas. I object insofar as intellectual humility seems to demand much more than just limitation owning. For instance, let us imagine a professor who is acutely aware of his own limitations. He also justifiably believes that he is better than most of his students in physics. With this realization in mind, he looks down on them with contempt as his intellectual inferiors. Even when they understand, he lectures patronizingly making sure they recognize his superiority. He acts this way not only toward his students but to all whom he justifiably believes to have less intellectual acumen. Additionally, he jumps at every opportunity to mention his success and prominently displays his awards and accomplishments wherever and whenever he can. To summarize, he is both aware of his limitations and responds appropriately. He is also, however, aware of strengths, wants everyone else to be so aware, and thinks these strengths entitle him to treat intellectual inferiors contemptuously. It is counterintuitive that such a professor is intellectually humble (to say the least).

Perhaps anticipating the aforementioned objection, Whitcomb et al. argue that “proper pride” (2017: 530) is the virtue that is concerned with our strengths. Perhaps this is so, but it does not follow that strength is irrelevant to humility. We might respond appropriately to our weaknesses and yet fail miserably in regard to our strengths and hence fail to be humble. For these reasons, I think the Limitations Owning View at best tells half of the story.[7] In the next section, I will do my best to tell the rest.

3. Profanities and Entitlement

3.1. Virtues: Personal and Interpersonal

In addition to overlooking strengths, The Limitations Owing Account makes the all too common self-assessment error. Like other theorists, Whitcomb et al. understand intellectual humility as self-reflective rather than other-reflective. This section details the specific problems with self-reflective accounts and also lays the ground work for an other-directed theory.

In earlier sections, we discussed something peculiar about self-assessment accounts. It seems fishy that a core moral virtue is so self-focused. So my first proposal is that humility cannot be described without reference to others. In other words, humility is an interpersonal rather than a personal virtue.

The way I am using the term, not all virtues are interpersonal, although many are. Courage and temperance are arguably personal virtues. We can imagine that a person on a deserted island, let us call him Rob, is courageous insofar as he jumps off cliffs, chases scary animals and swims in stormy waters. We can also imagine that Rob is incredibly temperate; he has the self-control to store food for the winter, go hunting when he would rather sleep, and endure the hot sun as he waits to catch fish. It is much harder to think of the ways that Rob might be humble without invoking dispositions toward others. Maybe Rob does not think too highly of himself, but without comparison, what this means is unclear. For clarity, let us formalize:

Personal Virtue: If virtue V is a personal virtue, then V can be adequately described while referencing the virtue holder alone.

Interpersonal Virtue: If virtue V* is an interpersonal virtue, then V* can only be adequately described with reference to agents other than the virtue holder.

3.2. A First Glance at Intellectual Humility as an Interpersonal Virtue

While there is clearly disagreement over just what constitutes intellectual humility, I suspect we can more quickly agree on who is not intellectually humble. Consider this example:

SAM: Sam, a second-year undergraduate, always arrives late, sits in the back of the class with a bored expression on his face, and every so often makes comments which either (1) suggest that he is right and his classmates are wrong and stupid, or (2) suggest that he is right and his professor wrong and stupid. Sam is immune to constructive feedback. Not an assignment goes by in which Sam does not complain about his grade, demanding that it be adjusted upward in light of his own genius and his professor’s obvious mistake.

I hope most can agree, that whatever else we might say of Sam, the one thing he is not is intellectually humble. It is also helpful to note that Sam exemplifies many of the vices Roberts and Wood have described as “the counterparts of humility.” According to Roberts and Wood this includes: presumption, haughtiness, self-righteousness, domination, selfish ambition, and self-complacency (2003: 257–258). And this is where I see us coming together, for the listed vices can be grounded in the common description of a certain sort of person. Those disposed to arrogance, egoism, pretentious and the like are everyday examples of, well, assholes. My suggestion is that if the humble person is anything at all, he is not an asshole. There is something painfully unfitting in the following assertion: “Toby is such a sweet, humble, guy. But what an asshole!” Let us turn to the detailed account of assholes recently put forth by Aaron James in hope that it might shed light on humility. According to James,

A person counts as an asshole when, and only when, he systematically allows himself to enjoy special advantages in interpersonal relations out of an entrenched sense of entitlement that immunizes him against the complaints of other people. (2012: 4)

Looking at the above definition, let us notice that both James and Roberts and Wood focus on the notion of “entitlement.” Roberts and Wood note that “humility is a disposition not to make unwarranted intellectual entitlement claims on the basis of one’s (supposed) superiority or excellence” (2003: 2050–2051). There is clearly something about “a sense of entitlement” that is particularly off-putting. And off-putting in a way that is likely incompatible with humility. With helpful reference to Roberts and Wood and James, the gist of my proposal is that the humble person is the opposite of the asshole. In other words, I will begin my analysis of the humble agent by describing just who he is not. With that in mind, a person is intellectually humble just in case he:

- Respects the intellect of others as his own, and so rarely feels immune to their complaints and criticisms.

- Systematically declines intellectual advantages in interpersonal relations because he feels no sense of entitlement.

Persons who meet these criteria tend to behave in ways that signify their intellectual humility. For instance, the intellectually humble:

- Rarely demand special intellectual treatment, even when deserving.

- Often refuse special intellectual treatment, even when deserving.

- Tend to take complaints and criticisms seriously, even when the criticizers are not authority figures and even when the criticism is rude.

- Tend to take the ideas (which are not always complaints) of others seriously, even the ideas of intellectual inferiors.

Like those who subscribe to self-assessment accounts, I do believe the intellectually humble lack abrasive overconfidence, but they lack this overconfidence specifically because it is incompatible with other-directed respect. I also believe that the intellectually humble, for the most part, own their own limitations. But this is because they take advice and criticism seriously, not the other way around. An interpersonal (anti-asshole) account can save “personal virtue intuitions” while avoiding downfalls of a purely personal virtue theory. Those who refuse to revisit opinions indeed lack humility. This, however, is best explained in terms of the complaints and disagreements that are surely being dismissed. Along similar lines, an obnoxious professor convinced of his own superiority indeed lacks humility. However, this is best explained not via overconfidence, but rather in the offhanded dismissal of disagreeing parties.

We can now understand the intuitive appeal of self-assessment accounts without needing to accept them. For example, the self-reflective character trait of overconfidence appears incompatible with intellectual humility, and hence theorists are tempted to define the virtue in terms of its absence. But on my account, we can explain why the humble are rarely overconfident without using this characteristic as a defining feature. The intellectually humble agent is one who has a deep respect for her intellectual community. Knowing that others disagree with her, she can rarely in good faith overestimate the epistemic appeal of her own views. She is ever aware that good folks disagree; this awareness tempers her intellectual brashness. Even in instances when the humble agent is quite sure of her beliefs, she does not flaunt this assurance. Her reasoning often runs along the following lines: “I am fortunate to have come down on the right side of things. Many intelligent persons have gone wrong, and in another world I may have been one of them.” Thoughts like this are not examples of the humble agent doubting her beliefs, but rather examples of the humble agent doubting that her own intellectual brilliance made arriving at those beliefs inevitable. The humble agent’s respect for reasonable and intelligent others tempers not her enthusiasm in p, but rather her enthusiasm in “look how special I am to believe p.”

Like the absence of overconfidence, limitations owning is a common trait of the intellectually humble agent that arises from her interpersonal habits. The intellectually humble agent, in an important sense, is one who always obeys the “intellectual golden rule.” She views the intellect of others as she views her own, rarely seeing herself as entitled to this or that intellectual privilege. Of course, it is important that we do not take this too far. Direct epistemic access to our own intellect puts us in a privileged position vis-à-vis the self. Hence, there is some sense in which our own epistemic evidence is especially weighty. The intellectually humble agent “discounts” for this privilege and then gives others the epistemic credit that they both morally and epistemically deserve. When she does so, she is very often forced to face her own limitations. After all, for those who are not too proud to ignore them, the world and its inhabitants are constantly putting checks on the epistemic limitations of even the intellectual best of us. Journal referees, students, colleagues, friends, and enemies alike, are there to tell us when and where we went wrong (whether we did or not). The intellectually humble agent (like all of us) is frequently bombarded with these whistle blowers; she is forced to face where she may have gone wrong. And when she is so forced, she does not feel entitled to dismiss the criticism; indeed, she is especially responsive to it. It is this sort of intellectual disposition which explains why the intellectually humble agent tends to own her limitations.

3.3. Intellectual Humility and Low Concern for Status

As with overconfidence and limitations owning, my account can explain the appeal of what Roberts and Wood saw as intellectual humility’s defining feature (low concern for praise) without having to accept it as a defining feature. I have already mentioned that I find Roberts and Wood’s account compelling: it is quite plausible that those who are intellectually humble are not overtly concerned with praise. In any case, exemplars of the clearly not intellectually humble are those obsessed with intellectual praise: the graduate student who has his walls papered with awards dating back to elementary school, the professor who becomes noticeably defensive when his ideas are challenged, and the colleague who is constantly tweeting about his new publication (and his older publication, and the forthcoming one too, and …) In contrast, the intellectually humble academic might not bother to update his CV and website (if he has a website at all), or if he does have one and does so bother, he does so begrudgingly and with noticeable discomfort taking part in such a self-aggrandizing practice. Along these same lines, the humble intellectual is rarely if ever defensive in talks and welcomes criticism with genuine openness regardless of the critic’s pedigree or prestige. In short, it appears that the arrogant intellectual agent is obsessed with praise while the humble one cares very little. I want to suggest, however, that more is going on here than immediately meets the eye.

The characteristic which manifests in persons who are prima facie humble is not a low concern for status, but rather a special concern for others. The humble person sees himself in the same light as he sees all others. So, while there may be occasions when he mentions his own accomplishments, he is just as likely to mention the accomplishments of others. It is not incompatible with humble behavior to link to one’s own publication. The humble person, however, is just as likely to link to the publication of another. Intellectual humility is exemplified in treating the intellect of others like the intellect of one’s own. This absence of self-privileging can come across as a lack of self-concern.

According to Roberts and Wood those who are vain are especially concerned with praise, and those who are humble are especially unconcerned. My account, however, raises rather than suppresses the importance of peer approval. It is because the humble person so greatly respects peer opinion that she can so greatly appreciate their praise and approval. Contra Roberts and Wood, we can imagine an agent who cares a lot about the praise of her peers but is nonetheless remarkably humble. Consider the following example:

Doctor Humbleton: Doctor Humbleton is presenting his work at the annual student/faculty research conference. He has been working hard for months on his paper, “Methods of Student Assessment.” His talk is indeed well received by students and faculty alike. Dr. Humbleton is happy to have the support of his colleagues and he thanks them profusely for all their help. He is even happier, though, to receive the praise of his students as he had been focused on making his paper accessible.

I find it intuitively plausible that Dr. Humbleton lives up to his name. He seems like a guy we would like as a colleague: someone who is concerned both with scholarly contributions and with helping his students. He is definitely not an asshole. Rather than assume his work will succeed, however, Humbleton is aptly attentive to colleagues and student opinion. Because he respects their intellect he both appreciates and desires their praise. And now we can take a closer look at the thesis of Roberts and Wood.

Although vanity, an excessive concern for praise, seems in conflict with humility, this is only because we are imagining this desire manifest in particular ways. (As Roberts and Wood say, the vain person is concerned about status, “for the sake of status itself”). Roberts and Wood describe vanity not so much as a trait manifesting excessive concern for praise, but rather a trait manifesting a presumptive entitlement to praise. C. S. Lewis has argued that, “if you want to find out how proud you are the easiest way is to ask yourself, ‘How much do I dislike it when other people snub me, or refuse to take any notice of me, or shove their oar in, or patronise me, or show off?’” (2009: 122). The person who lacks humility (and for simplicity we can loosely call this individual “a prideful person”) is oversensitive. They are not just hurt when others snub them or ignore, them, they are angry at those who do not give them what they think is their rightful due.

We should be clear that while a sense of entitlement to intellectual praise is in conflict with intellectual humility, the mere desire for praise is not. Those who are intellectually humble may very well be hurt when others do not take note of their work. A person who completely lacks humility, however, will be not only hurt but be angry and resentful. Rather than a humble sentiment of, “I wish others paid attention to my work,” the prideful sentiment is, “I cannot believe those fools did not give my work the attention that it deserves.” Lewis’s above statement seems right in the following way: the greater the angry entitlement in response to lack of attention, the less humble the individual. If we then apply this to intellectual matters, the greater the angry entitlement to one’s intellectual work, the less humble the intellectual.

4. The Finer Details

In the previous sections, we saw that while Roberts and Wood explain many important features and associated features (like the absence of a sense of entitlement) of humility, they ultimately go wrong in defining the virtue in terms of a low concern for praise. The humble person might or might not desire praise; and when that desire is present it stems from the intellectually humble agent’s respect for the intellect of others. The intellectually humble professor, for instance, might engage in the following:

- (1) He recognizes his own intellectual superiority.

- (2) In spite of (1) he listens to each opinion carefully.

- (3) He is motivated to do (2) because he respects the intellectual autonomy and ability of his students, even in spite of (1).

- (4) He occasionally revises his own opinion in light of his student’s thoughts.

A professor who exemplifies (1)–(4) seems just the sort of person we might call intellectually humble. My account explains this in systematic terms: our descriptions of intellectual humility latch on to an interpersonal virtue characterized by an absence of entitlement alongside a disposition to seriously consider the comments and complaints of both peers and non-peers.

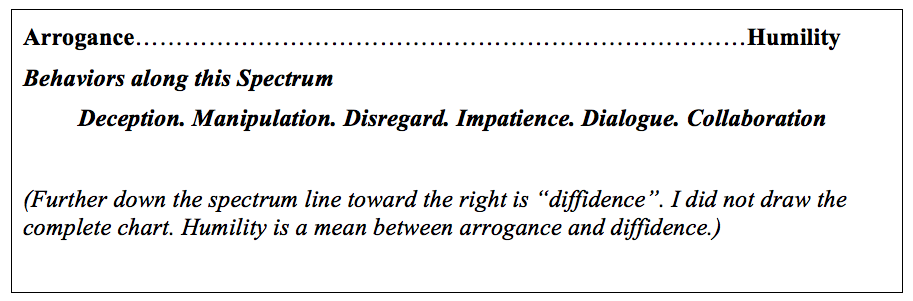

In contrast to (1)–(4), the intellectual asshole is consistently disrespectful. He operates with an entitlement to manipulate, deceive, and ignore; these are all hallmark manifestations of intellectual disrespect. On the flip side, the intellectual asshole is especially disposed to dismiss criticism for he is especially disposed to see his own rationality as “above” that of so many, many others. Intellectual Humility can be viewed on a spectrum of “Intellectual Respect.” Here is a model:

We see that for conceptual purposes, intellectual arrogance is grounded upon disregard for intellectual autonomy. Behaviors commonly associated with this disregard include deception and manipulation. In an important sense manipulators and deceivers attempt to control. Salient examples are found in cults and extremist political parties. These groups not only disregard intellectual autonomy, they act to undermine it via engagement in the following:

- (1) Attempt to manipulate persons into holding certain beliefs (truth need not matter).

- (2) Will try to achieve (1) regardless of the evidence.

- (3) Will try to achieve (1) without concern for the intellectual process of manipulated agents.

The line between innocent attempts at convincing others of p and malicious attempts of manipulating others is often a fine one. In both convincing and manipulating, there is a sense in which you attempt to get another to believe specific things. The difference lies in the way in which the manipulator demonstrates a sense of entitlement and control. The “convincer”, unlike the manipulator, cares that an agent comes to her belief through acceptable epistemic means. Those who are intellectually humble would, all other things equal, prefer that others believe the wrong thing than that they believe the right thing via manipulation or deception. In contrast, intellectual arrogance is not caring about this. The more important that a testifier believes her cause, the more likely she throws intellectual humility to the wayside. Evangelical religious adherents might think that religious truth is so important that they are justified in telling half-truths as a means to get to whole ones. Professors, also, might think it is so important that students learn certain truths that they give up on their students acquiring appropriate reasoning habits. Those who are intellectually humble, however, are the types who feel extremely uncomfortable in engaging in these suspect epistemic practices. Speaking more generally, the intellectually humble feel extremely uncomfortable in overriding the intellect of fellow rational beings.[8]

5. A Hybrid Concession: Interpersonal Assessment Intellectual Humility

In this section I want to pause and throw an olive branch in the direction of those sympathetic to self-assessment or limitation owning views. Even though I have made my case for why self-assessment and limitation owning is not essential to intellectual humility, someone with such views can take one of the most significant aspects of my account, the interpersonal aspect, on board. Indeed, the following view is one that Whitcomb et al. can adapt, as their account already has interpersonal features. This hybrid version of my view would indeed involve an assessment of the self; however, such self-assessment would necessarily be described in interpersonal terms. This virtue of intellectual humility would consist of owning one’s own limitations in special light of interpersonal communication. Hence in response to feedback, disagreement, and collaboration, intellectually humble continually reflect on their own limitations so that they might become improved members of their epistemic community. Self-reflection would be seen as a tool that aids one’s development as a faithful member of a collective epistemic enterprise. A speculative definition of this dual-theory account runs as follows.

Interpersonal Assessment Intellectual Humility: Agents are intellectually humble just in case interactions with members of their epistemic community creates a tendency to reflect on their own epistemic limitations.

Under the above, agents who habitually yet independently reflect on their own intellectual limitations would have features similar to the humble agent but would yet be missing a critical component. Such a character trait would hence fall short of true intellectual humility. Perhaps such an agent would be comparable to an especially polite person that lacked the empathetic attitude necessary for kindness. Intellectual humility contrasts with epistemic conscientious, insofar as the former disposes an agent to understand his own intellect as a tool for something beyond personal epistemic enrichment. Intellectually humble agents see themselves as one collaborative member of a broader community. Hence their own intellectual improvement cannot be viewed in isolation. Acquiring more true beliefs is not necessarily valuable, for not all true belief acquisition is collaborative, and intellectually humble agents see epistemology as stretching beyond their own intellectual scope.

Intellectually humble agents (of the interpersonal assessment variety) recognize others as critical to their personal epistemic life, an epistemic life that consists of membership in a community. They are acutely aware of the way in which a separate intellect has the purview to identify epistemic errors that individuals themselves are prone to miss. Moreover, collaborators can point out epistemic failings that are especially salient to the varied intellectual goals of the community at large. These two values of interpersonal epistemology are what separates intellectually humble agents from agents who, due to their own conscientious self-assessment, are often mistaken as humble. Recognizing epistemic errors and a corresponding willingness to correct them is a nice trait but it falls short of intellectual humility. Intellectual humility (according to the interpersonal self-assessment account) requires that self-assessment be inextricably intertwined with the assessment and opinion of others. Intellectually humble agents recognize that epistemic excellence is rarely (if ever) acquired on one’s own.

Having just made a case for a hybrid account that combines my emphasis on the interpersonal nature of humility with both self-assessment and limitation owning features, it is reasonable to wonder why this is not the account I myself support? I could have proposed this view as my central thesis, as maybe a modification to the limitations owning view rather than proposing an account in modest opposition.

The reasons I prefer my own account may seem to some as distinctions not worth much of a difference—and that might be for the better. As I see it, if humility is recognized as an interpersonal virtue (of any sort) we have made a big conceptual leap forward. Yet I still want to reject self-assessment as an essential facet of intellectual humility. I have already covered the main reasons, but let me emphasize once more: assessing the self is just not a priority of the intellectually humble. Self-assessment might enter the picture here and there, but it is not a focus much less a conceptually necessary ingredient. The disposition that characterizes the intellectually humble (according to my account) simply does not much concern itself (for better or for worse) with one’s own epistemic merits.[9] Notwithstanding, in response to engaging the intellect of others, humble agents are prone to change their own position and expand their personal understanding. Engaging in these transformative endeavors commonly demands reflection on individual epistemic shortcomings. Moreover, the disposition to show deference to an intellectual community sits uncomfortably with a refusal to admit mistakes. Hence those who are intellectually humble are often disposed toward limitation owning and even self-assessment. These tendencies, however, are derivative from the disposition to treat the intellect of others like one’s own. I still contend the habits of limitation owning and self-assessment are a byproduct of intellectual humility, not constitutive of it.

6. Intellectual Humility and Politeness

When discussing my thoughts on intellectual humility, I was asked the following question: Are you talking about intellectual humility or just “epistemic politeness”? My first response is that the two possibilities are not mutually exclusive. Perhaps those who are disposed to intellectual humility are also disposed to epistemic politeness. This should not be controversial. Politeness, at least in one sense of the term, consists of social norms that function as a means to display respect. Along similar lines, intellectual humility demands respect. Notwithstanding, my account is not equivalent to any plausible understanding of intellectual politeness. Intellectual humility demands much more.

Politeness can be what it is even if it is all just an act. The following is perfectly intelligible: “Beware of Scott. He is polite but he could not care less about anyone in lower management.” What this hypothetical observation suggests is that one can be both polite and an asshole. Although most who are polite are not assholes, most of us know a few people who fit into both categories and they are especially malicious. With polite assholes, you can miss the danger that is to come. Humility, on the other hand, is not only incompatible with assholism but is its direct contrary. It is not good enough to pretend to care about other intellects, the concern must be sincere. This is what can render humility so difficult. It is easy to pretend to care, actual concern is another story. Biases can be powerful, especially intellectual biases. If we believe p we also believe that those who believe p believe truly. Intellectual humility can cause cognitive conflict. We must continue to believe p but also listen to someone who believes the opposite. This is why intellectual autonomy is so central to intellectual humility: concern for the truth cannot breed intellectual humility by itself. We hold many beliefs with extreme confidence, often for good reason. What then, will get us to listen if not a search for truth? The answer is this: respect and appreciation in another’s quest for truth. Central to intellectual autonomy is each individual’s ability to use her own truth-seeking cognitive powers. Those who are intellectually humble recognize this as an intellectual good and this motivates them to listen to others they know are wrong.

7. Why Intellectual Humility is a Good Thing Intellectually

I have argued that intellectual humility is an interpersonal virtue that need not directly improve the virtue holder’s own intellect. Rather, as an intellectual virtue, intellectual humility’s primary benefits might be to other intellects. Imagine that an intellectually brilliant, generous, and humble professor devotes his summer to tutoring undergraduates. Imagine that at the summer’s completion, the professor’s time spent on basic intellectual matters put a small dint in his analytic acumen; he forgot a few things and his understanding of the subject is worse than when he started tutoring. This need not speak against the professor’s intellectual virtue. Much the contrary, by sacrificing his own intellectual wealth he has enriched that of others.

Let me be clear that I am not suggesting we turn to utilitarian principles to understand intellectual virtue. Rather, I am suggesting a “big picture” approach. First, intellectual virtue stretches beyond knowledge, true belief, and personal epistemic betterment. While this has been challenged in the literature, the dominant approach seems to still be narrowly focused on knowledge, true belief, and perhaps understanding. This narrow focus is at the expense of more general intellectual goods like honest inquiry, autonomous thought, careful reasoning, etc. I think the aforementioned processes are good things in themselves, apart from the good ends that they tend to produce. For example, honest inquiry is an intellectual good even if such inquiry does not lead to true belief. Intellectual humility is hence intellectually valuable insofar as it fosters a tendency to engage in honest inquiry and other valuable patterns of thought. Moreover, intellectual humility is valuable in a second, perhaps more salient sense which was exemplified in the just mentioned example of the summer school professor. The value lay not in improving the virtue holder’s own epistemic life directly. As an interpersonal virtue, intellectual humility allows its holder to improve the intellectual life of others. Because the virtuous agent plays a role in this improvement, her own intellectual character improves indirectly. Intellectual humility is intellectually valuable insofar as the virtue holder makes the world a better epistemic place by bestowing epistemic goods on other agents.

8. Conclusion

In this paper, I offered an alternative account of intellectual humility. Reading through the existent literature, I had noticed that something (in my own humble opinion) seemed a bit off with many accounts. I noticed two common faults. The first is that many described the virtue as a self-assessment virtue. The other is that most accounts described the virtue as a personal one. In contrast to much of the literature, I have argued that intellectual humility is both other-reflective and interpersonal. The intellectually humble person does not see herself as intellectually entitled; this allows her to treat other intellects with as much respect as she treats her own. This, in turn, leads to the intellectually humble agent aiding the intellectual improvement of other agents. Being intellectually humble might not aid one in the acquisition of true beliefs, but this virtue will aid the intellectual community in its entirety. Above all, the intellectually humble person is not an intellectual asshole.

Acknowledgments

I want to express my thanks to the following individuals: two anonymous Ergo referees, Heather Battally, Sven Bernecker, Paul Bloomfield, Margaret Gilbert, John Greco, Hanna Gunn, Jeff Helmreich, Michael Lynch, Casey Perin, Duncan Pritchard, Daniel Howard-Snyder, Dennis Whitcomb, and Matt Zwolinski. I am also grateful to the following institutions: University of California, Irvine, University of Connecticut; John Templeton Foundation and Saint Louis University.

References

- Adler, Jonathan (2004). Reconciling Open-Mindedness and Belief. Theory and Research in Education, 2(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878504043440

- Aristotle, and C. D. C. Reeve (2014). Nicomachean Ethics. Hackett Publishing Company.

- Baehr, Jason (2011). The Structure of Open-Mindedness. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 41(2), 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1353/cjp.2011.0010

- Bommarito, Nicolas (2013). Modesty as a Virtue of Attention. Philosophical Review, 122(1), 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1215/00318108-1728723

- Brennan, Jason (2007). Modesty without Illusion. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 75(1), 111–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1933-1592.2007.00062.x

- Carter, J. Adam and Emma Gordon (in press). Open-Mindedness and Truth. Canadian Journal of Philosophy.

- Church, Ian M. (2016). The Doxastic Account of Intellectual Humility. Logos & Episteme, 7(4), 413–433. https://doi.org/10.5840/logos-episteme20167441

- Driver, Julia (1989). The Virtues of Ignorance. The Journal of Philosophy, 86(7), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.2307/2027146

- Hare, William (1979). Open-Mindedness and Education. McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Hazlett, Allan (2012). Higher-Order Epistemic Attitudes and Intellectual Humility. Episteme, 9(03), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2012.11

- James, Aaron (2012). Assholes: A Theory. Doubleday.

- Lewis, Clive Staples (2009). C. S. Lewis Classic Collection: Mere Christianity. Harper One.

- Montmarquet, James A. (1993). Epistemic Virtue and Doxastic Responsibility. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Riggs, Wayne (2003). Understanding Virtue and the Virtue of Understanding. In Michael DePaul and Linda Zagzebski (Eds.), Intellectual Virtue: Perspectives from Ethics and Epistemology (203–226). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199252732.003.0010

- Riggs, Wayne (2010). Open-Mindedness. Metaphilosophy, 41(1–2), 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9973.2009.01625.x

- Roberts, Robert and Jay Wood (2003). Humility and Epistemic Goods (Linda T. Zagzebski, Ed.). In Michael R. DePaul (Ed.), Intellectual Virtue: Perspectives from Ethics and Epistemology (257–279). Oxford University Press.

- Spiegel, James S. (2012). Open-Mindedness and Intellectual Humility. Theory and Research in Education, 10(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878512437472

- Whitcomb, Dennis, Heather Battaly, Jason Baehr, and Daniel Howard-Snyder (2017). Intellectual Humility: Owning Our Limitations. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 94(3), 509–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12228

- Zagzebski, Linda T. (1996). Virtues of the Mind: An Inquiry into the Nature of Virtue and the Ethical Foundations of Knowledge. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174763

Notes

There is an endless array of literature I might cite to demonstrate the centrally of humility to various religions and strains of moral thought. There is not, of course, time for this in a footnote. Yet here are just a few illustrative examples, so the reader might get a taste of the general sentiment. From The Bhagavad Gita, “Be humble, be harmless, have no pretension” (13:7–8); From the Qur’an “Successful indeed are the believers who humble themselves in their prayers and who shun vain conversation” (Surah 23:1–3); “Becometh as a child, submissive, meek, humble, patient, full of love…” (Book of Mormon, Mosiah 3:19). The compilation of these quotes was found at http://serenityweb.com/?page_id=80.

I will discuss work on not only humility, but also humility’s close cousin or cogent, modesty. Unless otherwise noted I use the terms interchangeably. Many authors have used the terms interchangeably. At the very least, modesty and humility are virtues that seem specially related.

As Nicolas Bommarito has noted, “This account of modesty [Driver’s account] has seen more than its fair share of attacks (see Statman 1992; Maes 2004; Raterman 2006; Brennan 2007; and nearly anyone else writing on modesty since Driver)” (2013: 95). It should not be surprising that the criticism of Driver’s view coming from the perspective of intellectual humility is just as strong. For epistemologists and ethicists alike then, there is something very unsettling about a virtue being dependent upon ignorance (Socrates has made his mark). I agree with these general criticisms. My greatest concern is that ignorance of the self is a vice, and a foundational moral virtue like humility should surely not depend upon a moral vice.

Unfortunately, I will not have time to discuss all accounts in the prolific literature. Rather, I analyze a select set of theories of particular relevance to the purposes of this paper.

There are two camps within the intellectual humility literature. On the one hand, there are theorists who advocate what we might call “reliabilist” views of intellectual humility, and we can say that those who disagree take a “responsibilist” stance. The former understands epistemic accuracy as a central part of intellectual humility, the latter is less focused on accuracy and more focused on what might seem like a “moral” stance on the virtue. This paper is discussing only responsibilist positions and is itself taking a responsibilist stance. For those interested in reliabilist intellectual humility, see Church (2016), and Hazlett (2012).

Nicolas Bommarito also mentions limitations owning: “One of the qualities that makes a Gandhi or a Mandela so great is the relationship they have with their own goodness; they refrain from tooting their own horns and instead seem to focus on their own limitations” (2013: 93–94).

Whitcomb et al. do address concerns very similar to my own. I am not satisfied with their response. One line of argument they use is an example of a diffident agent who does not own her own strengths. Whitcomb et al. argue that if humility involves owning one’s strengths, then we would have to conclude that this diffident agent is not humble enough. This conclusion, they suggest, is odd. I admit that calling the diffident student ‘”too humble” is odd. However, I think it is even odder and even more counterintuitive to have an account of humility that allows for the types of arrogant behavior that are displayed in my above example.

What I am describing as intellectual humility might appear similar to open-mindedness. However, what matters for open-mindedness is not so much listening to the ideas of others (as is central to intellectual humility), but rather the willingness to change one’s own beliefs. Imagine that an open-minded agent has thoroughly considered the possibility of proposition p from all perspectives. The next day this open-minded agent might decline to listen to a friend opine about p. An intellectually humble agent would listen to this friend nonetheless, for listening would serve an epistemic purpose not for the sake of the humble agent but for the sake of the friend. (Humble agents often put the intellectual needs of others ahead of their own, while the open-minded agent need not do this). If one is interested in the literature on open-mindedness, some important works include Adler (2004), Baehr (2011), Carter and Gordon (in press), Hare (1979), Riggs (2003; 2010), Spiegel (2012), and Zagzebski (1996). Spiegel directly addresses open-mindedness and intellectual humility.

In this way, I am much in agreement with Nicholas Bommarito’s “attention” view of modesty (which he says is interchangeable with humility). Bommarito argues that the modest person is one who does not pay much attention to the self (2013: 93).