Synergizing Analogue Inquiry With Digital Tool Use in Graphic Design Ideation

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

David Lancashire is an Australian graphic design practitioner whose broad experience of the industry’s transition from utilizing analogue to digital technologies has transpired over more than five decades of practice. Examining how his ideation processes have evolved affords us a unique opportunity to study how his use of specific materials and his employment of particular tools have informed his and others’ abilities to construct knowledge and fuel inquiry and curiosity in and around the decision-making processes that guide ideation in contemporary graphic design. This learner-centered approach to analysis is rooted in the learning methodology known as material inquiry.[a]

Lancashire is a member of Alliance Graphique Internationale — a group of over 500 graphic designers and artists from over 40 countries — and a past board member of Icograda (this organization has since come to be known as the International Council of Communication Design, or simply “ico-D;” it is an international organization that has existed since 1963 that is comprised of over 120 smaller organizations around the world that together advocate in various industry and governmental settings on behalf of the profession of graphic design and its practitioners). In 2018, I completed doctoral research at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) that examined how and why Lancashire’s analogue (as opposed to digitally facilitated) graphic design methods continued to play significant roles informing his design decision-making over the roughly three decades since the advent of graphics applications software and the platforms they run on. [1] As I initiated this study, I chose the term ‘material literacy’ to define the degree of a graphic design practitioner’s ability to understand and apply various types of technological knowledge — both analogue and digital — during the evolution of his, her or their individualized processes of designing. The following article re-evaluates the potential for creative autonomy in graphic design practices so broadly affected by the operation of digital technologies in two ways. The first involves sharing findings about how material experimentation has figured continuously in Lancashire’s graphic design-rooted ideation since he began practicing in the 1960s. The second explores the high degree of invention that has infused his working processes as a result of his ability to consistently explore various aspects of material experimentation. Highlighted throughout this exploration are examinations of how and why materially focused methodologies that can be adapted for effective teaching in contemporary graphic design education settings. In turn, these contribute to current debates about how the utilization of digital tools have affected and are affecting the practice of contemporary, mainstream graphic design. Specifically, they address John Hartnett’s request for discussion on the topic in his article The Programmed Designer, [2] in which he states, “We might consider graphic designers as labourers whose work generates surplus value for Apple and Adobe.”

Introduction

My deep exploration of Lancashire’s ideation processes from the beginning of his career in the 1960s and the completion of my study in 2018 yielded key insights about how his design ideation was affected more by his use of analogue tools, while his design processes that involved making and manufacture were affected more by his use of digital tools (since they were introduced to graphic designers in the late 1980s). Because so many of his methods for employing analogue tools during the ideational phases of designing can still be applied today, my research into his use of these yields knowledge and understandings that have the potential to inform contemporary graphic designers. Additionally, his methods for employing analogue tools and means, such as papercuts, ink, and handheld mark-making devices, to guide his ideation processes are essentially inventive, and, as such, can also be incorporated into the functional development of future technologies that graphic designers can someday use to facilitate the ideational development of their work.

The primary thesis being asserted and extended in this piece contends that there exists a connection between the extent of someone’s material literacy and the degree of creative autonomy available to contemporary graphic design practitioners as they engage in the ideation processes that inform the creation of their work. (In this context, material literacy refers to knowledge of and about how using given materials contribute to understandings rooted in the provenance, lifecycle and socio-economic, technological and environmental issues associated with the use and after-use of various materials by those who study and practice graphic design.) Also asserted is the potential for a broadening of the impact of extending the material literacy of graphic design practitioners on the scope of discipline’s future artistic and commercial prospects. Not only does the high level of inventiveness inherent in Lancashire’s methods (and the outcomes these yield) confirm the relevance of analogue processes in a world of contemporary graphic design that has become so largely facilitated by digital means, but, as the descriptions of these presented in this article will reveal, his methodologies are widely available for interpretation by today’s technologically experimental practitioners. This means that digitally fluent contemporary graphic designers can seek or create working conditions informed by analogue-based processes within which they can generate ideas to produce different, and perhaps more effective and authentic, outcomes than design processes that evolve exclusively within the digital realm. [3] The idea that conceiving designs in ways that account for material and technological capacities has been well researched in architecture, industrial design, and other areas of design practice since the middle of the 20th century.This article will articulate the argument that conceiving and developing design outcomes in ways that account for the effects of utilizing a wide variety of material and technological capacities — analogue and digital — to inform ideation is also still germane to graphic design in this the third decade of the 21st century.

Developing a Material Consciousness

David Lancashire was born in Manchester, U.K. in 1953. Despite being told that, as a working-class kid growing up in an environment not particularly known at that time to be supportive of the visual arts, he could not become a visual artist, he began pursuing an artistic life at an early age (Figures 1 and 2). His Auntie Maude enrolled him in The Circle School in Stockport at the age of eleven. It was here that his teacher, John Henshall, an artist, musician, poet, and calligrapher, introduced Lancashire to graphic design through his ideas, tools, and techniques (Figure 3). His consciousness regarding the potential for design-rooted invention and innovation that could be achieved by working with different materials developed in accordance with the professional, non-digital technologies available for generating graphic design work at the time (i.e., during the late 1960s and early 1970s). He learned to design in part by observing and enacting how various analogue tools could be manually manipulated. He witnessed Henshall extract and apply finely drawn typographic forms from gold leaf to applications that could be made on substrates such as vellum and wooden plaques, and, as he did this, learnt the fundamental, formal design principles of shape, contrast, negative space, rhythm, repetition and tonal gradation when Henshall temporarily removed color from his students’ tool sets.

By tasking his students to work only in brush and black ink for a period of several weeks to help them better understand these fundamental design principles, Henshall also indirectly introduced them to professional reprographic techniques such as the preparation of mechanical art using halftone screens. Lancashire’s first paid graphic design work was undertaken at Industrial Art Services (IAS) in Manchester, a commercial art studio with clients as diverse as the U.S.-based animation studio Hanna Barbera, and the U.K.-based department store Marks and Spencer. [4]

In 1966, at Henshall’s encouragement, Lancashire migrated to Sydney, Australia. By the mid-1980s, his own practice, David Lancashire Design, (DLD), was operating in full swing in Melbourne. The archival source of his design work that informed my study was comprised of more than 90 boxes of this material that had been transferred to the RMIT University Design Archive in 2014. This work represented much of the output of DLD’s printed practice up until that time. Whilst a broad knowledge of and understandings about analogue tools and methods to use them permeates this work, what emerged as being more important to my thesis was the identification of Lancashire’s understanding of the connection between technology and purposeful designing. Because Lancashire did not have to contend with the monopoly by the likes of Adobe and Microsoft that limits the digital tool choices of contemporary graphic designers, he was able to exercise and experience the benefits inherent in selecting from a wide variety of analogue tools to utilize in the production of his work. He was also afforded the opportunity to choose which among these tools was right for specific tasks. Success with this approach incorporated tacit recognition of a correlation between material variety and new design ideas, and also informed the development of a set of methods dependent on access to the capabilities that could be operationalized by using an extensive variety of tools. Because of his interest in and experience with fine, or “studio,” arts, the tools he used to produce this type of work often guided the evolution of his graphic design work. His combined fine art and reprographic knowledge became means that Lancashire utilized to expand the expressive potential of working within the constraints imposed by having to meet the expectations of graphic design clients while producing work that effectively communicated with their target audiences.

Whilst DLD was one of the first studios in Melbourne to invest in computers (and the graphics application software that run on them) in the 1980s, Lancashire chose not to learn to operate these new digital systems and tools. He made this choice not only to preserve his access to all available inventive means, but also to avoid committing his imaginative reserves to learning the operation and capabilities of a single, complex-to-use set of tools. In contrast to most graphic designers in practice today, Lancashire was able to adapt a methodology for invention in the digital environment based on exploring the use of combinations of both digital and analogue tools to execute his ideas. Lancashire thus evolved a working method that allowed him to conceive of graphic design ideas that employs analogue tools for fundamental ideation and then digital tools to further develop the production of these. The physical diversity of the artifacts that constitute Lancashire’s archive of work and the breadth of technological resources discovered to have helped guide so much of its development is a consequence of this decision. As the examples later in this article will depict, Lancashire managed to create formal and conceptual diversity in his graphic design work by diversifying the array of physical materials he utilized during his processes of ideation. He remained responsive to qualities as tangible as those that became evident to him as he worked with various types of paper, and as nebulous as those that can be drawn from lived experience, such as the time spent creating art and graphic design work in the Australian desert. [5]

Repurposing

My interviews with Lancashire about the evolution of his work made it clear that seeking to purpose or re-purpose materials and technologies to unprescribed uses was not only a central theme of his practice, but a principle that guided his methods for conceiving and developing design ideas. An aspect that seemed to pervade Lancashire’s consciousness was and is a predisposition for computing what adaptions different materials can withstand within the constraints imposed by different working parameters and environments (Figure 4). When asked to describe the link between his design processes and his use of materials, Lancashire answered by mentioning experiences such as observing of the colors and patterns of birds’ eggs, or learning to cut fabric across the grain as an essential part of the process of fashioning neck ties. Acknowledging his propensity to adapt, and, speaking directly to the position of creative autonomy to which his methods entitle him, Lancashire qualified these experiences by making the point: “If you know how something is made, you can make it in your own way.”

To help me understand the extent of the importance of this kind of stimulant, Lancashire emailed me a photograph of himself at work from the 1960s in the early days of his career in Manchester, U.K. “Did you see the hinge?” he asked when he phoned afterwards to make sure that I had seen its depiction of how a barn door hinge had been repurposed to move a light back and forth across the desk. He then described the tools seen to its right and recalled how he had propped brushes on pieces of e-flute cardboard to prevent them from rolling across it, to protect the structural integrity of their points, and to prevent the desktop from being inadvertently splattered with ink (again, Figures 1 and 2). Lancashire’s lateral way of entering the conversation — offering his observations about an image he had provided — highlighted his admiration for the ingenuity typical of a business that “ran on the smell of an oily rag.” He was appreciating what he perceived as the instinct for invention.

Paper: Sketching Substrate or Sketching Tool?

The following sections of this article describe examples of how such perceptions and actions are realized in Lancashire’s design process. In these, paper is the material that he seeks to repurpose. His archive exhibits decades of immersion in exploring a wide variety of possible transmutations of paper, and his practice exists as one within an extensive history of exploring the symbiotic relationships that exist between paper companies and graphic designers. The Strathmore Paper Company employed designers such as Oswald Cooper and Saul Bass to operationalize the “paper in use” strategy in the 1950s and 1960s, whereby compositions designed specifically to inspire other graphic designers are put into production and disseminated across the graphic design and advertising industries as the twentieth century progressed. The West Virginia Paper and Pulp Company (also known as Westvaco) similarly employed Bradbury Thompson to design their in-house publication Westvaco Inspiration for Printers between 1939 and 1962. [6] Mutually beneficial, the arrangement allowed paper companies to promote how well their various paper ranges supported available printing technologies, such as embossing, die cutting, foiling and folding, and allowed designers to factor in the possibility of using specialty papers and labor intensive, expensive techniques to support their design ideas. Attracted by the inventive prospects of the field, DLD was in part sustained by multiple commissions from Australian paper companies. Essential to the argument for the continued significance of analogue materials in post-digital graphic design, it is important to stress that Lancashire’s paper manipulation and paper making knowledge are vital skills that he has developed over the breadth of his entire career, and constantly deployed (and still deploys) in his work, and that his choice to conceive designs by responding to the physical characteristics of analogue materials allows him to produce outcomes that are not achievable with computers.

By quite literally handling a type of paper stock to ascertain its formal qualities as his began his various commissions from paper companies, Lancashire was experimenting with ideas that involved promoting specific stocks by highlighting their inherent capabilities. This also allowed him to simultaneously interpret the physical significations in the changed forms that appeared in various papers as he folded, cut, shaped, or marked them by hand.

A comparison of two of Lancashire’s designs that are informed by exploring the physicality of paper exemplify the role that gaining a material understanding of a given paper stock can play to stimulate ideation in ways that guide the evolution of the graphic design process. These designs have been selected to explain Lancashire’s ability to apply his perceptions to different technological circumstances, as well as to provide deeper insights into the complexity of his engagement with paper, including knowledge of how it is made, and how, whilst designing, he finds ways to correlate this knowledge with other fixtures of his imagination. Both designs express his experience of time spent in the Australian desert. Made more than two decades apart, the die-cut folder and the hand-cut collages appear remarkably similar. A deeper analysis of these artifacts also provides an explanation for why Lancashire seeks to repurpose paper as a drawing instrument, rather than using prescribed drawing tools such as a pencil out of force of habit.

While Lancashire conceived both designs manipulating paper by hand, one is an expensively produced, mechanically die-cut folder commissioned to encase a range of specialty papers in the 1990s (Figure 5), and the other is a set of economically produced, noncommercial collages completed in 2018 (Figure 6). In both pieces, undulating lines cut the paper to signify desert hills and to create an overlayment of shapes that creates the illusion of distance. In the folder, these were rendered with a metal printing knife, and, in the collage, with a handheld scalpel. These shapes are unfixed on the folder, which allows it to be opened and closed, and are fixed in place by glue in the collage.

The anthropologist Timothy Ingold refers to such materially focused methods of making as a “co-respondence” between a mind and a material, which poses an alternative to the concept that the mind imposes fully formed ideas onto a material. [7] For example, the torn irregular line of one of the collaged hills is as much created by the make-up of the paper as Lancashire’s decision to tear it to reveal its fibers, which allows the fibers to play a role in conveying rough, sandy desert textures. In doing this, Lancashire had identified and employed his recognition of a correlation in the particle make-up of paper and the desert; pulped particles make up paper and geological particles constitute much of a desert landscape. However, referring again to the concept expressed in the statement, “if you know how something is made you can make it in your own way,” Lancashire’s knowledge of the fibrous make up of paper was essential to his acknowledgement and enactment of this opportunity. A materially literate design consciousness is as equally attuned to noticing technological particularities as it is to devising adaptations for them. Tool psychologists Osiurak, Jarry and Le Gall noted that tool perception is designed for action. [8] In this case, Lancashire’s knowledge of the fibrous make-up of paper combined with his artistic judgement to decide that the addition of an area of roughness in the composition would more truly reflect the sandy desert textures than a design cut entirely with a knife. Such negotiations between the mental and the technological are typical of materially focused, tacit and strategic, graphic design knowledge in operation.

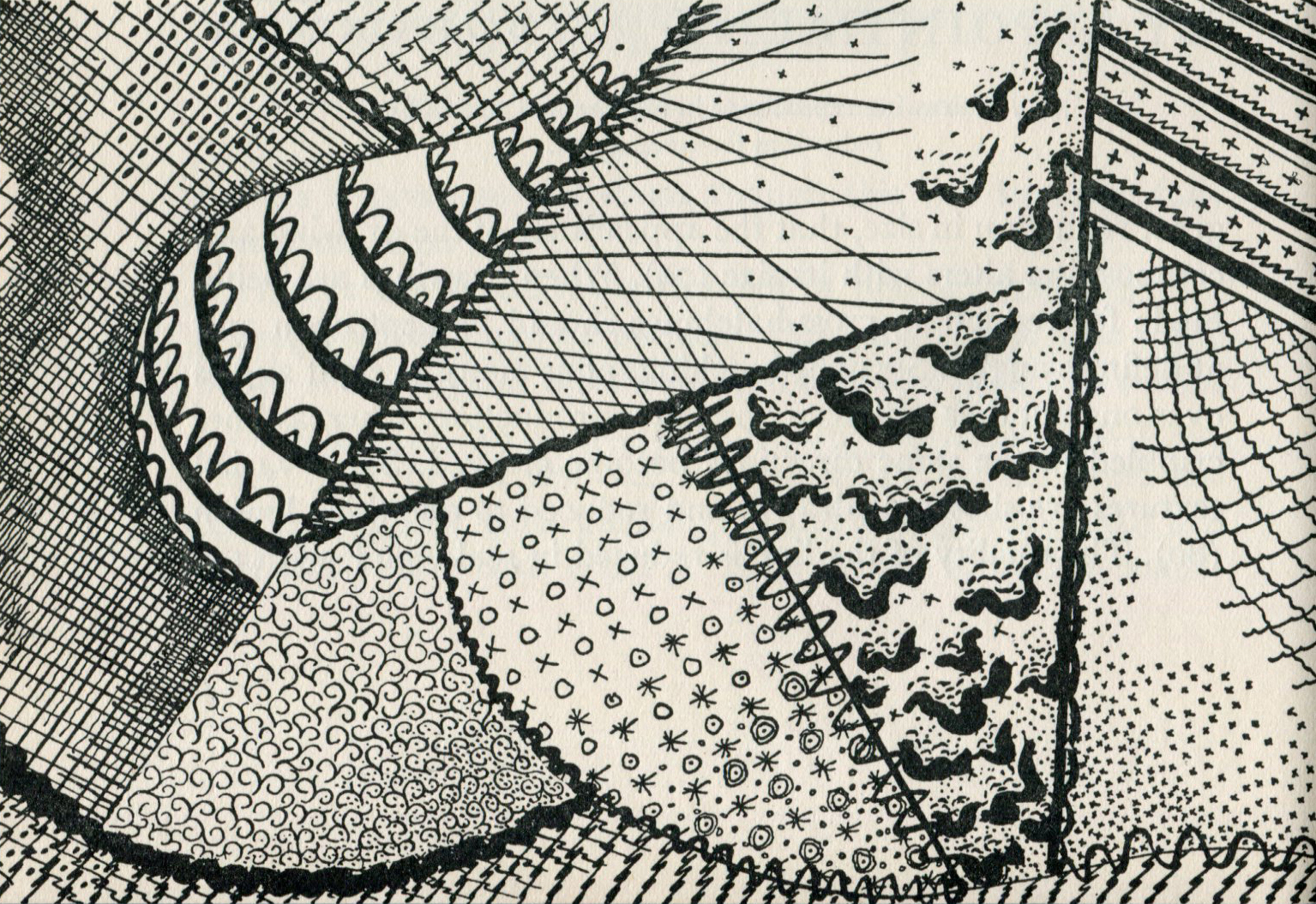

Lancashire’s seemingly casual comment in one interview, “I’ve got to stop drawing,” echoed Matisse’s decision in 1952 to progress from painting with brushes that were prescribed for that singular purpose, to cutting colored paper with scissors to stimulate new inventive opportunities. Like Matisse, Lancashire was seeking a different “criterion of observation” [9] by attempting to make a technological change in his working practices. When Lancashire renders hills with purpose-built drawing instruments such as a pencil, paper is an inactive recipient of his mind’s concentration on the capabilities that drawing with a pencil make possible. For example, rendering pattern and grading tone from dark to light are achievable by using a pencil to create the necessary transitions (Figure 7). However, using controllable instruments diminishes opportunities for accidental occurrences to intervene in the creation of work. On the other hand, cutting paper with scissors more immediately generates less predictable results. Because the process is relatively quick, there is less time for the mind to control the process and more opportunity for the action of the paper, the scissors and the hands to intervene. Lancashire hastened spontaneous results by choosing to cut pre-patterned paper. Tacit understandings about material propensities and possibilities develop from interactions such as these and become embedded in the designer’s intrinsic knowledge that guides future design decision-making.

Examining a Kind of Tool Making: Fostering the Process of Designing Paper with which to Design

The accrual of material knowledge such as in the example above, are seldom experienced in the profession today, largely because ubiquitous, prescriptive digital tools have removed for most graphic designers what was once a creative imperative — the involvement in the making of their tools. Most practitioners today are more likely to spend time managing continual software updates than actually making their own tools. Lancashire’s teacher John Henshall ground gesso from pumice stone to emboss his designs, and he gilded them with gold leaf applied with a long brush made sticky with nose grease. To equip himself with an “art-like” substrate for high-volume mechanical production inspired by the colors and textures he found in the Australian desert, Lancashire took it upon himself to design and propose a paper stock for Australian Paper to manufacture. His confident knowledge of the papermaking process and how it could be varied was imperative to this choice. He supplied a hand-mixed swatch of colors, dirtied by a touch of black or blue “to knock them back a bit” to Australian Paper for them to mix with flecked, granular paper pulp. In a later interview about this process, Lancashire acknowledged the sensitivity of natural beauty and the importance of his perceptions of its intangible features for his work in the comment, “I always look at nature for color before a Pantone swatch book.” [10] Once produced, Lancashire worked closely with printers and paper embellishment specialists to effectively paint the paper’s surfaces with print embellishment techniques such as intaglio, raised verko printing, foil stamping, embossing and debossing. Originally titled Terra Australis, Lancashire melded his technological and design knowledge to engineer Outback, a unique suite of designs that, reflecting his childhood ambition, blur the boundary between art and graphic design, (Figures 8 and 9). Upon seeing ‘Outback’ retrieved from its archive box, Lancashire raised the set of conditions he often seeks to combine with his material expertise in the remark, “That wouldn’t have happened without Kakadu,” crediting time spent in Australia’s Kakadu National Park as crucial to the inception of that work. His advice, “I would encourage every young designer to go bush, roll your swag out, and soak it up. Reconnect regularly with the environment, then see what happens to your work,” [11] subjugates angst about technology by reminding us that creative autonomy in graphic design ultimately exists in the imaginations of those who practice it.

Implicit to Lancashire’s use of materials is the knowledge that they also often perform as signifiers in visual communication, and, in turn, affect how these act, can be made to interact, and can be determined to play roles as essential contributors to a given design process. As detailed earlier, Lancashire decided to add a torn section of paper to a collage because he knew an irregular edge would help him to convey the grittiness of desert textures. Intrinsic to this knowledge is knowledge of how to resource materials to convey particular meanings and evoke specific emotional responses, as well as understandings about what connotations particular materials can help guide, and how the communication of these within a given system can be managed. These types of knowledge are not exclusive of digital tools. However, regarding the creative empowerment of post-digital designers, a limited tool set confines the possibilities to which imagination can be exposed, thereby restricting the creative potential of the discipline. The argument here is, rather than accepting a digital tool monopoly in contemporary graphic design, find ways that analogue and digital tools can coexist in the contemporary graphic design toolbox.

Repurposing Mechanical Tone and a Photocopier

Something Lancashire brought from the U.K. to Australia was a knowledge of a wide variety of reprographic techniques. While enrolled in Henshall’s classes, he practiced grading tones from black to white using India ink. Later, while he was employed at Industrial Art Services in Manchester, he adhered mechanical tone to illustrate tractors and prepare catalogues for production. Whether conceived for reproduction or not, and whether produced by hand or machine, Lancashire repurposes stipple as a tool to patina featureless surfaces. For Lancashire, “Pattern is the patina of life ... [broken surfaces help] you become part of things by letting you see through the layers of life ...” [12] The patterns that feature in the collages and the folder already discussed were generated using a 1980s color photocopying machine. Inspired by David Hockney, Lancashire repurposed photocopiers as “texture making factories.” Attesting to its fit-for-purpose construction and the extent of his reappropriation of it, Lancashire said in interview, “We broke it all the time. I put color papers through, turned the paper around and put it through again. I forced it to take heavy papers that it wasn’t designed to take. The repair guy couldn’t believe how often he visited the machine to get it going again.” [13]

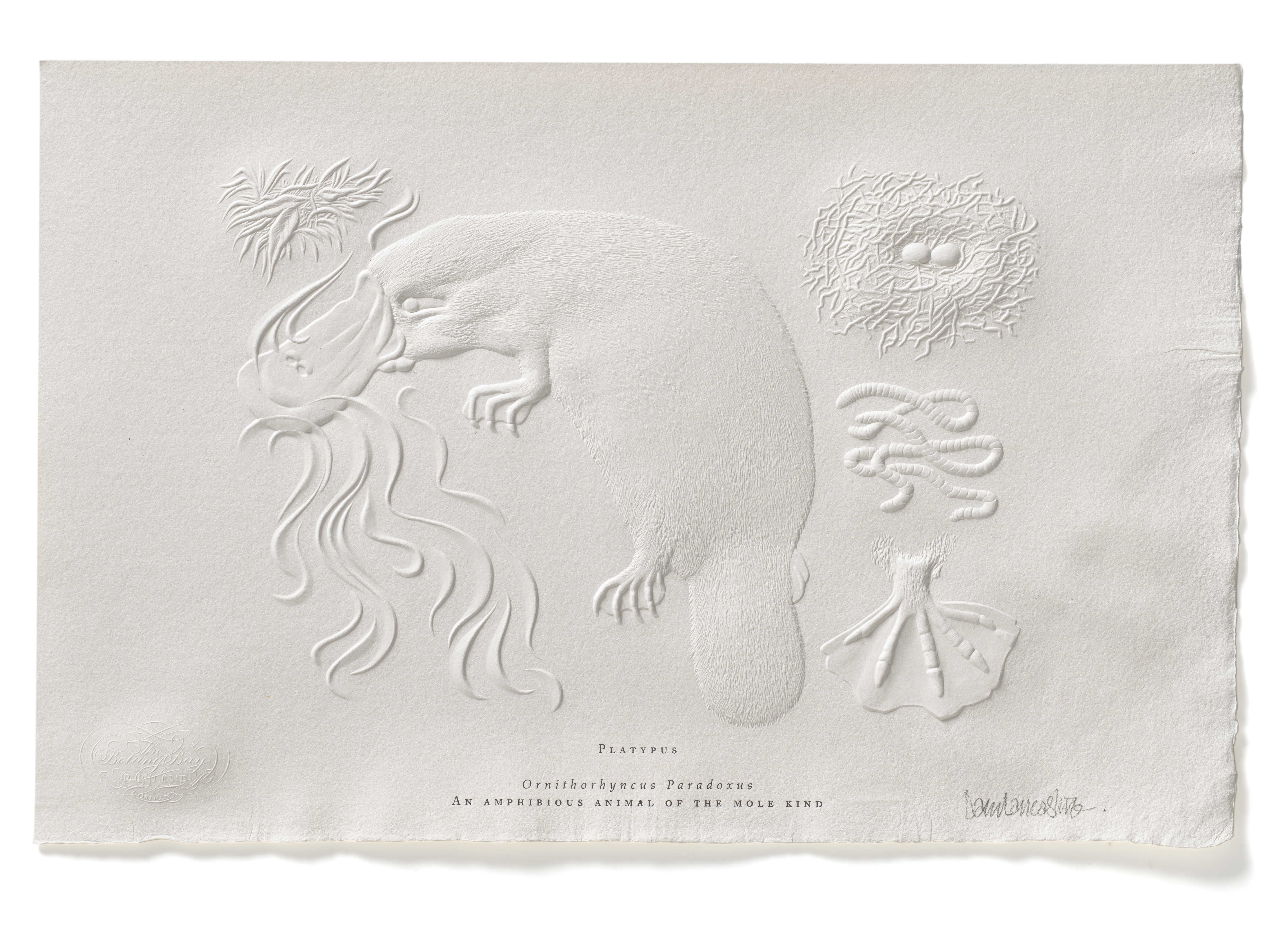

“To make them like gems”

Lancashire does not believe that graphic design needs be confined to the production of ephemera, and therefore seeks circumstances within which he can produce graphic design artifacts of permanence, stating, “We wanted to make things that people would want to keep, to make them like gems.” To realize this aim, a technique that features noticeably in his archive is sculptured embossing (Figures 12 and 13). Its prevalence demonstrates the value Lancashire saw in pursuing paper industry clients for access to the machinery and master technicians connected to each commission. Embossing is a mechanized process that presses imagery into paper using a male-female mold, where light captured on the paper’s surface reveals design results that can be reminiscent of carvings made in materials such as marble, shell, or ivory. Referred to as “blind” when ink is not used, the technique is best suited to robust, long-fibred papers. The artistic expertise of engraver, Richard Clark, employed by embelishment experiments Avon Graphic, was essential to the success of DLD’s embossed designs. With tools like those of a jeweler, Clark carves mostly into brass, but sometimes uses softer magnesium for larger designs.

Conclusion

John Hartnett, author of the piece The Programmed Designer that was published in Eye Magazine in 2017, rightly draws attention to the limits imposed on creative autonomy by digital tools upon which graphic designers are so currently dependent. He raises concerns about the limited imaginative scope available to future outputs from the discipline if these are only conceived and developed by designers who rely exclusively on digital tools. The primary assertion articulated by Hartnett is the existence of a connection between the extent of a practitioner’s creative autonomy in the design process and the extent of that practitioner’s material literacy, (once again: material literacy is defined as the breadth of experience one has working with a variety of tools with which to conceive and execute design and other artwork.) This is not a discussion about making a choice between analogue or digital tools, but instead cites the importance of considering any available tool to invent or discover a design outcome that is appropriate and visually communicative. Whilst the analyses of Lancashire’s designs appear to showcase qualities lost to graphic design as it is have evolved since the introduction of digital tools, the fundamental intention of this article is to suggest ways that technologically curious graphic design practitioners can reevaluate that approach. Whilst Lancashire utilized and gained working experience from using analogue prior to using digital tools, it is possible for today’s digitally native practitioners to invert the sequence of Lancashire’s technological discoveries and add analogue expertise to their digital expertise.

The analysis I have undertaken asserts that, as a materially focused graphic designer, Lancashire sought and still seeks to adapt his consciousness to particular technological situations to stimulate his imagination and encourage innovation, and that the thought-provoking tensions that arise from these adaptions are tacitly sought techniques to engineer invention. His methods and their outcomes exemplify a profound connection between creative autonomy and materially led design ideation. In response to Hartnett’s request for discussion, these findings suggest that teaching material literacy needs to become a focus of graphic design education as it is now taught in curricula heavily influenced by the operation of digitechnical systems. If new practitioners are taught that the tools with which they choose to work as they engage in design decision-making processes are critical — quite literally instrumental regarding what kinds of design outcomes they will be able to produce and how they will be able to produce them — these emerging designers can more effectively address issues rooted in autonomy. This will occur as they learn to make more conscious and broadly informed decisions at the outset of a design project regarding the materials they wish to use, all the while as they are fully cognisant of the fact that this choice will have a significant impact on the quality of their designs.

Without knowing or caring to know how to operate digital tools, Lancashire sought conceptual stimulation elsewhere. While he perceived that computers were useful for tasks related to precision and replicability, he drew from an imagination sustained successfully by the possibilities of handwork as a means to be able to resist working in the digital realm as his design work evolved. As necessary, he outsourced digital production work to preserve his access to all available inventive means, and to avoid committing his imaginative reserves to learning the operation and capabilities of a single, complex-to-use tool. His comment, “If you know how something is made you want to make it in your own way” speaks directly to his keen sense for generating ideas by adapting a wide variety of technologies, and gains pertinence when considered in relation to his choice at the time. The unseen, expensive, and electronic workings of computers and the software that runs on them did not invite tinkering in the 1980s the way they do today. Decades later, amidst digital ubiquity, it is easy to imagine Lancashire reconfiguring computers for design purposes the way he did print technologies.

A final, practical takeaway from the study of Lancashire’s practice is a note about Lancashire’s attitude about the arrival of digital tools. Because he was introduced to graphic design in an era when multiple analogue tools were available for general use by designers, and their various capabilities were sought and tailored to meet the demands required during their engagement with specific tasks, and he had experienced success assessing these materials for different purposes, he was able to regard digital tools as an extension of his analogue tool set rather than a replacement for it. From this technologically fluent position, Lancashire adapted a methodology that is recommended for diversifying the conception methods of today’s digitally-focused graphic design students — to practice methods of conceiving and evolving their design work by making use of analogue tools, while reserving the use of digital tools until the time comes in the design process for the finite development and reproduction of whatever they have designed.

References

- Eames, C. 1971. “The New Covetables.” Charles Eliot Norton Lecture Series, Harvard University. Online. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cmpUOv4Wq1M. (Accessed February 28, 2018).

- Grigg, J. “Materials and Tools as Catalysts of Invention in Graphic Design Ideation.” Design Studies 70 (2020). Online. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0142694X2030048X. (Accessed May 24, 2022).

- Grigg, J. “Material literacy: The significance of materials in graphic design ideation, a practice-based enquiry.” (Ph.D. dissertation, RMIT University, 2018): pgs. 291–294.

- Gürsoy, B., & Özkar, M. (2015). “Visualizing making: Shapes, materials, and actions.” Design Studies, 41 (Part A): pgs. 29-50.

- Hartnett, P. “The Programmed Designer,” Eye Magazine, Summer 2017. Online. Available at: http://www.eyemagazine.com/feature/article/the-programmed-designer. (Accessed August 26, 2021).

- Hauptman, J. “Inventing a new operation.” In Henri Matisse: The Cut–outs, edited by N. Cullinan, K. Bichberg, J. Hauptman, and N. Serota, pgs.17–23. New York, New York, U.S.A.: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014.

- Hofstede, D. 2014. “Re:collection.” Last modified March 15, 2022.Online. Available at: https://recollection.com.au/biographies/david-lancashire. (Accessed May 18, 2022).

- Ingold, T. “Thinking through making.” Paper presented at “Tales from the North,” an international conference at the Sami Cultural Centre SAJOS, Finland, April 10–12 2012. Online. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ygne72–4zyo. (Accessed August 26, 2021).

- Kahn, Nathaniel. 2003. “My Architect: A son’s journey.” Distributed by New Yorker Films (New York, New York, U.S.A.). Online. Available at: http://www.Myarchitectfilm.com. (Accessed June 13, 2022).

- Killen, H. 2013. “Interview: David Lancashire.” Desktop Magazine, 290 (2013).

- Menges, A. 2012. “Material Resourcefulness: Activating Material Information in Computational Design”. Architectural Design, 82 (2): pgs. 34–43.

- Osiurak, F., Jarry, C., and Le Gall, D. “Grasping the affordances, understanding the reasoning: Toward a dialectical theory of human tool use.” Psychological Review 117.2 (2015): pgs. 517–540.

- Unknown. “The Advertising Programmes of 17 Paper Companies,” Print XII, (1958): pgs. 33-44.

Biography

Dr. Jenny Grigg is a practicing graphic designer and a lecturer in the School of Design at RMIT (Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology) University in Melbourne, Australia. During her professional career, she has fulfilled positions as an art director at Rolling Stone Magazine Australia, MTV Australia, and as a senior designer at the London office of the international design consultancy Pentagram. She has designed and guided the design of a wide variety of work on behalf of clients such as Faber and Faber, Granta Books, UQP and Scribe. This work has included designing books authored by Peter Carey, Paul Auster and Eleanor Catton, and currently includes an ongoing array of design commissions on behalf of Australian-based Giramondo Publishing. She has won multiple design awards over the course of her professional career, including a 2011 State Library Victoria Creative Fellowship and induction into the Design Institute of Australia’s Hall of Fame in 2020. Her research in graphic design history most specifically examines how material literacy has affected various approaches to ideation in graphic design.

- a

Material Inquiry is a methodology that can be used to critically examine and analyze how individuals and groups construct useful and usable knowledge and understandings as they familiarize themselves with how particular tools can be used to manipulate specific types of materials. An example of material learning is offered as follows: as a woodworker becomes more adept at using a given set of carving tools to manipulate the formal characteristics of a specific type of wood, he, she or they might also learn and become curious about various types of making and doing that can be effectively undertaken as a result of having gained experience working with that set of carving tools and that specific type of wood.

Grigg, Jenny. “Materials and Tools as Catalysts of Invention in Graphic Design Ideation.” Design Studies 70 (2020). Online. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0142694X2030048X. (Accessed May 24, 2022).

Hartnett, P. “The Programmed Designer,” Eye Magazine, Summer 2017. Online. Available at: http://www.eyemagazine.com/feature/article/the-programmed-designer. (Accessed August 26, 2021).

Eames, Charles. 1971. “The New Covetables.” Charles Eliot Norton Lecture Series, Harvard University. Online. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cmpUOv4Wq1M. (Accessed February 28, 2018). Kahn, Nathaniel. 2003. “My Architect: A son’s journey.” Distributed by New Yorker Films (New York, New York, U.S.A.). Online. Available at: http://www.Myarchitectfilm.com. (Accessed June 13, 2022). Menges, Achim. 2012. “Material Resourcefulness: Activating Material Information in Computational Design”. Architectural Design, 82 (2): pgs. 34–43.

Hofstede, D. 2014. “Re:collection.” Last modified March 15, 2022. Online. Available at: https://recollection.com.au/biographies/david-lancashire. (Accessed May 18, 2022).

Grigg, J. “Material literacy: The significance of materials in graphic design ideation, a practice-based enquiry”. (PhD diss., RMIT University, 2018): pgs. 291–294.

Unknown. “The Advertising Programmes of 17 Paper Companies,” Print XII, (1958): pgs. 33-44.

Ingold, T. “Thinking through making.” Paper presented at “Tales from the North,” an international conference at the Sami Cultural Centre SAJOS, Finland, April 10–12 2012. Online. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ygne72–4zyo. (Accessed August 26, 2021).

Osiurak, F., Jarry, C., and Le Gall, D. “Grasping the affordances, understanding the reasoning: Toward a dialectical theory of human tool use.” Psychological Review 117.2 (2015): pgs. 517–540.

Hauptman, J. “Inventing a new operation.” In Henri Matisse: The Cut–outs, edited by N. Cullinan, K. Bichberg, J. Hauptman, and N. Serota, pgs.17–23. New York, New York, U.S.A.: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014.

Grigg, J. “Material literacy: The significance of materials in graphic design ideation, a practice-based enquiry.” (Ph.D. dissertation, RMIT University, 2018): pgs. 291–294.

Killen, H. 2013. “Interview: David Lancashire.” Desktop Magazine, 290 (2013).

Grigg, Jenny. “Materials and Tools as Catalysts of Invention in Graphic Design Ideation.” Design Studies 70 (2020). Online. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0142694X2030048X. (Accessed May 24, 2022).

Grigg, J. “Material literacy: The significance of materials in graphic design ideation, a practice-based enquiry”. (Ph.D. dissertation, RMIT University, 2018): pgs. 291–294.