Design as a Catalyst for Empowerment: Lessons From Youth Design, a Design-Led After School Program for High School Students in Boston

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Design-oriented, after-school enrichment programs for pre-college students (aged roughly 16 to 18 years), which are also known as out-of-school or after-school programs in the U.S., often address or attempt to address issues around justice and empowerment[a] in underserved and urban[b] communities. Such was the case with Youth Design, a non-profit out-of-school program that, for fourteen years (2003–2017), served public high school students in urban settings in Boston, Massachusetts (U.S.A.). Although the program served hundreds of Boston-area youths in this age group (or “Youth Designers,” as they were referred to by those who managed and operated this program), the workings of this organization have not been well-documented in peer-reviewed design research literature. While design-based enrichment programs embedded within more established organizations and institutions have made inroads into sharing research and best practices,[c] “grassroots”[d] organizations such as Youth Design are often born out of the personal passion and dedication of activists and community leaders who found and sustain them in an effort to positively augment the learning experiences of students in this age group living in urban settings, or in direct response to a specifically expressed community need or social crisis.[e] Despite the earnest efforts of those who operate and volunteer their expertise within these types of programs, they tend not to be critically well-examined in the published scholarship that informs design education and design education research. Because of this, our understandings and bases of knowledge regarding the relative efficacy of these community-based programs is quite limited. For those who might seek to develop and sustain such programs, it can be challenging to fulfill scholarly inquiries about what has been done to plan, implement and operate these kinds of endeavors, as well as why particular decisions involving these came to be made, and what effect(s) these had and are still having.

Even after programs such as Youth Design in Boston cease to exist, the strategies undertaken to plan and sustain their operations can and should be critically assessed via examinations of whatever publicly attainable information and practical measures can be reviewed by design researchers, scholars, and educators. Models do exist for measuring the efficacy of similar justice-oriented community youth work.[f] These research approaches have given some structure to this research[g] by providing indirect assessment measures, such as examining program-related documentation embedded within mission statements, press publications and other documents, and interviews with and firsthand accounts from participants and leaders. As part of this case study, this author randomly selected[h] and interviewed past participants from the Youth Design program. This analysis of the qualitative data gleaned from these interviews provides a critical lens through which Youth Design’s stated goals were measured against the actual outcomes that affected the learning experiences of program participants.

If we are to gain better, more critical understandings of and about the value, structure, and outcomes of design-oriented after-school enrichment programs, it behooves us to gain more granular insights into such efforts and, at the very least, document the efficacy of what they achieve on behalf of other design researchers, scholars and educators who are also engaging in this type of research, or who are examining the collective history of these types of endeavors. This research is especially essential when, as this article demonstrates, design-oriented after-school programs can address and affect issues within and around social and economic justice, community functionality, equity, diversity and inclusion, and the effective bolstering of social mobility. Moreover, disseminating this critical design knowledge may provide future design leaders with accessible and actionable insights which they might be able to use to guide the planning and operations of their own design-based, after school initiatives.

Introduction

In April of 2022, during a panel discussion that was themed around transforming communities by involving various stakeholder groups in art and design initiatives, Marquis Victor, the founder and executive director of the non-profit youth enrichment and empowerment organization Elevated Thought in Lawrence, Massachusetts, U.S.A., was asked how he and his team think about and measure success. In answer to this question, Victor replied, “Our outcomes are captured in our stories. For example, when Elevated Thought alumni return to serve as mentors, [to new or newer students involved in this program] or participate in other ways, we share those stories and showcase them as examples of positive outcomes.” [1] Victor’s response mirrors precisely a response to the same question that this author received from Denise Korn several years earlier.[i] Korn, who founded the AIGA-supported Youth Design organization in Boston, also noted how Youth Design graduates often “gave back” — going on to serve as mentors, instructors, and supporters of the program. With this in mind, Korn encouraged this author to track down and speak directly with past Youth Design participants and capture their stories, as their narratives would help tell the story of the efficacy of the planning and operation of Youth Design firsthand. Thus, much of this paper is structured to articulate some of these stories, which function as both narrative and evidence. Secondarily, readers of this paper will gain a sense of the program’s structure, goals, and intent.

The Executive Summary of a 2006 study led by Sharon E. Sutton stated that “this country urgently needs social institutions that view urban youth not as problem-laden clients, but as individuals capable of struggling to eradicate the inequities in their lives and communities.” [2] To address that need, the study sought to examine “a small slice of the vast array of drop-in and structured out-of-school programs for youth.” [3] The study, conducted over a period of 29 months, encompassed 88 programs in urban[j] communities, with around 90% of the organizations considered grassroots by the authors. [4] In addition, the authors used aggregate data to chart the defining characteristics of these organizations onto a conceptual map. These characteristics fell into four categories:

- The context in which programs operate;

- The principles that guide their work;

- The content of their curricula; and

- Their self-reported outcomes.

This paper applies the four defining characteristics identified by Sutton to examine Youth Design — leveraging them here as broad conceptual frameworks that help situate this work.

Notably, Sutton’s study also provided “A Firsthand Look at Six Programs,” [5] which this paper models in its qualitative analysis of Youth Design. To assess each program’s “implicit philosophies,” Sutton analyzed “published mission statements and two open-ended survey questions.” These questions were,

- What are the primary reasons for offering the program activities?” and

- “Why do youth need programs like yours?” [6]

These general criteria and approaches were and are also helpful in assessing the Youth Design program in Boston.

Sutton and her colleague’s study provided empirical evidence that charted the characteristics of programs deemed to be more transformative — defined as “those [programs] that seek to engage low-income and minority youth in understanding and redressing the unjust conditions that hinder their development.” [7] In the case of Youth Design, transformation was specifically characterized through its goal of individual empowerment for those Boston-based high school students enrolled in its after-school activities. A critical examination of precisely what “empowerment” meant (and still means) among its participants in the context of the planning and operation of the Youth Design program will now be discussed, along with the particular aspects of these that contributed explicitly to helping participants become more empowered.

Origins and Content

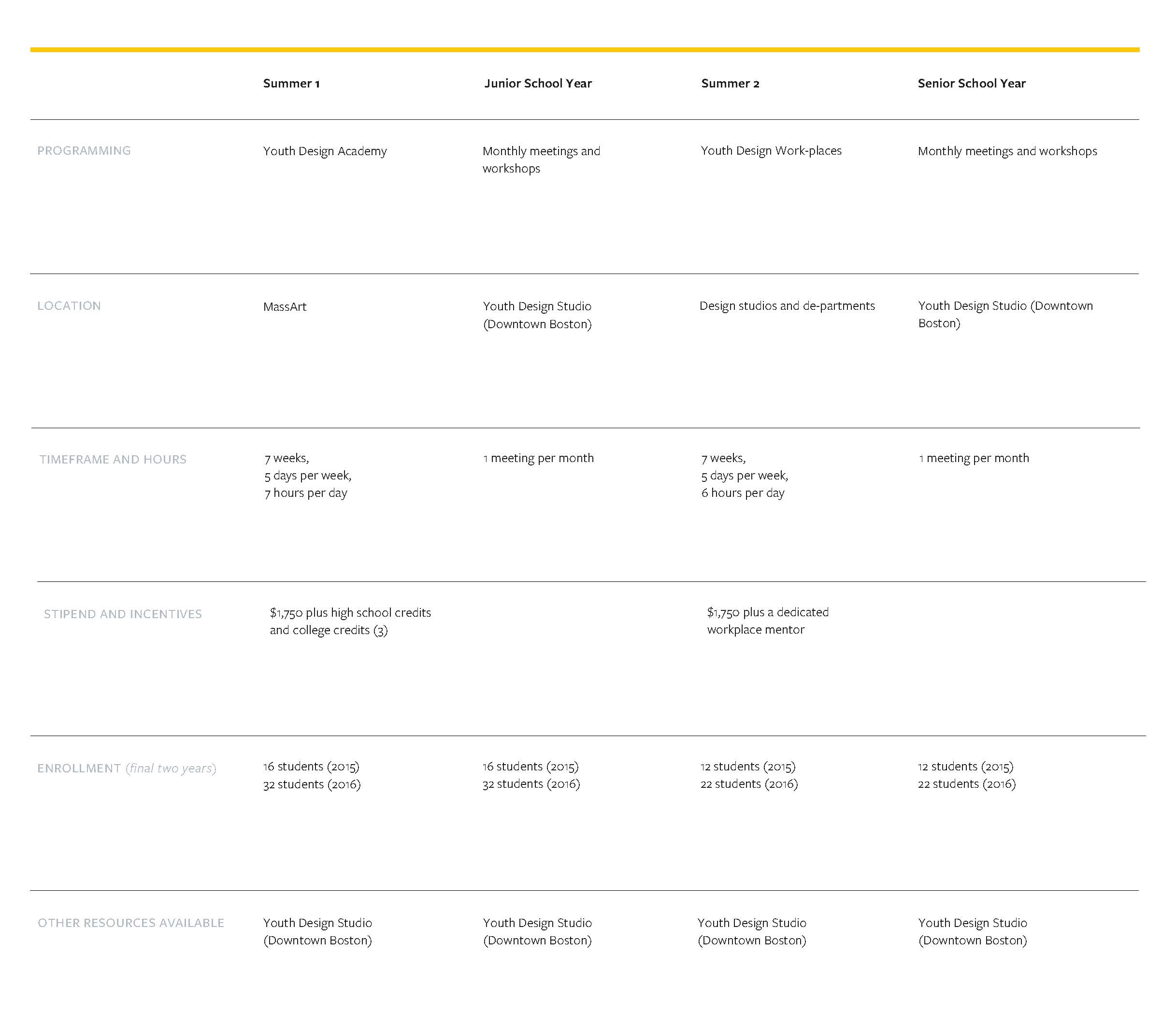

Youth Design was founded by Denise Korn, a Boston-based graphic designer and brand strategist in 2003. Her youth program (originally titled “Youth Design Workplaces”) initially offered seven-week summer internships/mentorships to ten or fewer high-school-aged participants. At its peak in 2016, what had evolved into Youth Design onboarded a cohort of 32 Youth Designers into what had become a two-year, year-round after school program. Korn viewed Youth Design as a “public-private partnership,” wherein the City of Boston represented the “public” component of the partnership, and professional design organizations,[k] Boston area design firms,[l] corporations, and institutions offered “private” support in the form of funding and mentorship.[m] The vast majority of Youth Designers hailed from urban Boston communities in and around the greater Boston area. For Korn, Youth Design was, “a way to expose urban teens to the design community.[n]

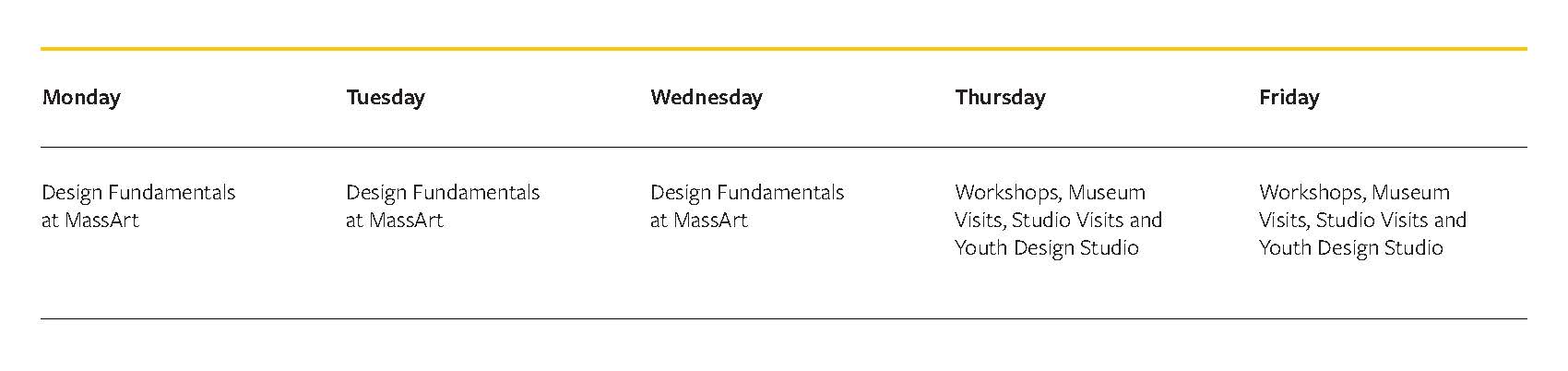

From its inception, the program placed Youth Designers in paid positions at leading design firms, creative agencies, and in-house design departments across greater Boston. After years of trial and error, Youth Design expanded to become a more comprehensive, two-year program. In year one, Youth Designers assembled for seven weeks during their summer vacation period to participate in Youth Design Academy (YDA), a for-credit academic design program. YDA met for seven hours daily, allowing the program to award participants dual academic credit (these consisted of high school elective credits and three college credits hours).[o] Three days were dedicated to Design Fundamentals (studio-based design training) (see Figure 2).[p] During year two, Youth Designers were afforded opportunities to work with various types of design practitioners and their collaborators on projects that involved a broad array of stakeholders, and, in some cases, clients.

By affording Youth Designers opportunities to work with professional designers and those affected by their design decision-making processes, Youth Design empowered its participants by including them in these, and by honoring their voices. [8] It also allowed the Youth Designers to have the power and privilege of adults shared with them as a means to improve various aspects of the lived experiences of both of these groups in the communities they share.

Seven years after she started Youth Design, Korn opened Youth Design Studio — a physical space in downtown Boston open to Youth Designers and a year-round “home base” for Youth Design participants and alumni to access a computer lab, studio, and study space. In addition, the studio provided students with a safe workspace monitored by second-year Youth Designers, alumni, administrators, and (volunteer) professional designers. With Youth Design Academy, Youth Design Workplaces, and the Youth Design Studio, the final cohorts of Youth Designers were engaged in year-round programming over two consecutive years (see Figure 3). This programming also included weekend workshops led by local designers, community leaders, and design educators throughout the school year. In addition, the workshops focused on design and “life skills,” including financial literacy, time management, and professionalism in the workplace. Youth Designers did not pay tuition, enrollment fees, or other expenses to participate in the program — rather, they were provided with a financial stipend[q] to support their enrollment within it.

Initially, the Youth Design admissions process was informal. Alex Barbosa, a Youth Design participant in 2008, learned of the program when Korn visited his high school (Boston Arts Academy). When interviewed for this article, he did not remember having to apply for enrollment within it.[r] As the organization grew — by 2015, Youth Design was receiving hundreds of applications annually — a formalized admissions process became crucial. Students were asked to complete an application and provide letters of recommendation from high school teachers and copies of their high school transcripts. Applicants were also prompted to present portfolios of creative work and attend in-person interviews with a group of Boston-area (volunteer) design professionals and design educators who evaluated them by assessing their answers to a series of questions regarding their plans for their immediate futures[s] and other personal data.[t]

Korn viewed Youth Design as a “platform for change,[u] and former participants (eight interviewed by the author) communicated some degree of positive, personal change occurring in their lives as a result of their participation. For example, former Youth Design participant Barbosa stated that “being immersed in a professional environment and having professional responsibilities at that age was truly transformative.” Barbosa added, “I had never had that kind of responsibility before Youth Design.” One differentiating feature of the program that surfaced in these interviews was that it was not participants’ engagement in design work that proved to be the catalyst for their transformations, but rather their experience working within a professional design environment over a sustained period of time. Several respondents spoke of suddenly becoming a “professional” via “being surrounded by professionals” in what was the first time for many of them. These critical accounts and reflections are shared in more detail in the Outcomes section of this article.

Context

Youth Design should be considered in the context of the broader “Design in K-12” movement in the U.S.A. In 1997, the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development published Design as a Catalyst for Learning. [9] This research project, led by American design education pioneer Meredith Davis, sought to document the state of design and how it could be further leveraged across the spectrum of K-12 education. In the publication’s Conclusions and Recommendations section, the authors state that, “some teachers confuse visual products (illustrated book reports, drafted plans for a house)” with “design problem-solving, in which students make critical choices that affect the quality of the environment, efficiency of products, and effectiveness of communication.” [10] Youth Design responded to these dilemmas not by integrating design into high school education but by providing external immersive workplace opportunities preceded by college-level (undergraduate) design studies. v These studies helped participants develop the formal, technical, communicative, and expressive aspects of design. To a lesser extent, these studies provided Youth Designers with an acute sense of how design can be employed as a mechanism for intentionality, strategy, and change.

At the same time, Youth Design also served its supporting organizations and the broader design discipline in and around Boston by helping to diversify it. According to Korn, diversifying the design profession[w] was one of the key motivating factors that drove her to create Youth Design.[x] On a webpage dedicated to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, AIGA states that “despite progress made over the course of AIGA’s 100-year history, especially since its landmark 1991 symposium (‘Why is graphic design 93% white?’), there are vast opportunities to support a more diverse audience of design students, practitioners, managers, thinkers, enthusiasts, clients, consumers, and policymakers.” [11] The opposite might also be true — that the “vast opportunities” are not, in fact, vast, but the challenges inherent in attaining these are. In her 2019 article The Co-Constitutive Nature of Neoliberalism, Design, and Racism, Lauren Williams wrote, “Some contemporary design practices–especially Design Thinking–tend to simultaneously compound and conceal the oppressive effects of both neoliberalization and racism.”

One way Youth Design sought to subvert design’s oppressive power hierarchies was by providing Youth Designers with income to learn about design (rather than charging them tuition or asking them to produce work for pay). At various points, however, some projects assigned to Youth Designers seemed to be concocted merely to placate some of the justice, equity, and inclusion issues that many of these students had to confront on an almost daily basis. Asking students to design a protest poster around a social issue perpetrated against them and their communities and then giving select students awards for “creativity” is but one example. While the intention of such prompts are understandable, such efforts, to Williams’s point, may often do little to turn the lens of criticality back upon design itself in ways that challenge design to question and alter the roles it plays in sustaining social and cultural inequities. These types of efforts also tend to be ineffective at moving design toward functioning as a solution provider, or a “situation improver,” rather than functioning merely as a problem identifier.

Principles and Supporting Narratives

In Chapter 2 of Sutton and her colleagues’ report Guiding Principles of Program Practice, the author attempted to assess each program’s “implicit philosophies.” To do so, Sutton and her colleagues analyzed “published mission statements and open-ended survey questions.” [12] Likewise, these approaches aid and abet the assessment of Youth Design.

Throughout its existence, Youth Design publicly shared the following mission statement: “Youth Design empowers talented urban youth to pursue a path to higher education and promising equitable careers by engaging the professional design community to mentor, educate, train, and employ the next generation of designers.[y] In its attempt to uplift talented urban youth, the program emphasized empowering individuals rather than reshaping oppressive systems, and to this end, Korn sought to “develop a platform that allowed students to focus on learning, experimenting, and expanding their point of view.[z] To be clear, the community-oriented aspect of the program was related to the design community, and “empowerment” was targeted towards the youth participant, but not necessarily their community. This article’s Conclusions section suggests that future programs might more effectively serve both.

Interviews with former Youth Designers confirmed that empowerment was central to their experiences of participating in this program and the learning-related outcomes they achieved as a result of taking part. Participants consistently agreed that exposure to environments and opportunities outside of those otherwise available to them helped foster this sense of empowerment. For example, in an interview with Yamilet Caceres,[aa] who participated in the program in 2013, she revealed that Youth Design “saved [her].” She explained, “having a low-income background and going to the high school I attended, many people said that there was no future... When I attended Youth Design, I began to see the world differently — and I saw what’s out there — that there’s more out there than just violence.” When prompted to reflect on the most important things that she took away from the program, she paused and replied, “I believe it gave me some sort of power... . It just shifted my entire life” and “gave me drive and enthusiasm.” Later in our interview, Caceres said that Youth Design helped her “see that [she] could do better.” She shared that she had just purchased her own home. This remark reflected her sense of personal achievement and offers evidence of the more profound impact that participating in Youth Design had had on her life, especially given the documented links between homeownership and wealth retention,[bb] and the disparity between white and non-white homeownership in the U.S.[cc]

Kenomes Reid, a Youth Designer in 2016, echoed Caceres’ point about purpose when, in a reflective essay written during his enrollment in the program, he remarked that he had found “purpose” in design. Through Youth Design Workplaces, Reid worked at the Boston-area architecture and planning firm Sasaki. Commenting on his time there, Reid said, “the steps the architects utilize in the design process and how they think intrigue me. [They] have pushed me to want to become an architect... . Hopefully, they will one day be my colleagues.[dd] This last statement is revealing in that it signals a perceived shift in power: They will someday be his colleagues. In our 2021 interview, Reid, now studying at a Boston-area college, stated that Youth Design provided him with the “mental fortitude[ee] that he could not acquire at his high school. Reid’s story raises paradoxical issues of “access and failure” [13] — or, more specifically, how increased access to the arts or design without another significant pedagogical revamping may “reinforce the persistent failure of urban schools to provide purposeful education.” [14] Thus, Reid’s aforementioned acknowledgment of purpose is significant — but perhaps not without caution, as finding individual purpose does equate to reducing or eliminating disenfranchisement. More socially, economically and politically widespread efforts are needed to achieve this, and design and design education do indeed have roles to play in these endeavors, but exploring them is fodder for an article with a different thematic focus than this one.

Several Youth Designers have pursued and completed university degrees in design. One example is Tamika Reid (no relation to Kenomes), who completed the Youth Design program in 2009 and went on to serve as a Youth Design mentor. She graduated from Pratt Institute in 2014 and went on to work at Proverb, a Boston design firm. [15] Reid is now a full-time Graphic Designer at UNIQLO. Like other interviewees, she said that she found Youth Design “empowering” but was quick to provide some critique. Reid suggested that Youth Design “could have rethought the kinds of ‘work’ assigned” to participants during their summer mentorships, noting that these projects and “tasks” might be better served coming from actual Youth Design participants or experienced design educators. Reid said Youth Design gave her “the confidence” to talk to her parents about a career in design. Ultimately, she said she believed that design, “translates to nearly everything that you interact with,” and that as she looked back on it, the design projects upon which she worked gave her a sense that, “she knew what she was doing,” and that Youth Design, “broadened her horizons” and “helped [her] see that there’s more out there.[ff]

While the program focused on mentoring individuals, more than one participant interviewed indicated that Youth Design could have done more to support alumni after they exited the program. For example, some of those, such as Alex Barbosa, who returned to Youth Design to serve as one of its mentors, felt better supported and connected to the program as a result of their ongoing participation in its evolution. As Youth Design grew in scale and capacity, paid staff became essential.[gg]

Questions and Conclusions

In her 2016 MFA in graphic design thesis, Jacinda N. Walker noted that, “Design is everywhere, but for many African American and Latino youth, the journey to a design career can be overwhelming. Limited access and too few opportunities prevent the majority of these youth from even beginning the journey.” [16] Walker went on to note, “The intent of this research is to inform and empower future African American and Latino youth, their parents and other educational stakeholders about the journey [necessary] to obtain a design-related career.” In the spirit of Youth Design, in 2016, Walker founded DesignExplorr, “an organization that operates as a social enterprise to address the diversity gap within the design profession. [17] DesignExplorr “aims to diversify the design profession by expanding access to design education for youth and raise awareness for corporate organizations. This work is accomplished through collaborations that develop youth activities, coordinating diversity-building initiatives, and connecting stakeholders to resources.” Walker’s work is noted here primarily for its clear emphasis on ways that (similar to Youth Design) it seeks to “inform and empower” African American and Latino youth in various urban settings across the U.S. While the intentions of DesignExplorr are clear, we must once again ask how these can be measured. While this article does not attempt to address this question definitively, it does attempt to employ the “what” and “why” questions utilized by Sutton and her colleagues, along with narratively gathered and analyzed evidence, as suggested by those who immersed themselves in organizing and facilitating this type of work, such as Marquis Victor and Denise Korn.

In one of our interviews, Korn offered that one of her few regrets was “not developing Youth Design within a more robust or design-centric institution.[hh] Perhaps this institutional support could have assisted Youth Design with succession planning, and, in so doing, this may have helped Youth Design sustain itself beyond the summer of 2017. Perhaps this type of support could also have provided the resources needed to track participant outcomes qualitatively. Critically examining these issues allows us to explore some of the tension rooted in this kind of work. For example, during the transforming community panel discussion mentioned at the outset of this piece, Marquis Victor also clarified a need to set boundaries with institutions. He stated that, “we [at Elevated Thought] are cautious about whom we bring in, and whom we partner with — especially those who may just be looking to check a box.” [18] This tension between grassroots organizations’ autonomy versus institutional entities’ power and support is undoubtedly an issue that future design leaders and youth program facilitators will have to continue to grapple with.

Setting those issues aside, the effectiveness of Youth Design in fulfilling its mission over its 14-year existence can be directly measured in part by its participants’ levels of academic achievement. Of the approximately 700 students who participated in the program, [19] all graduated from high school. Nearly all went on to post-secondary education, with many choosing to study design or art-related majors. [20] More than half of those this author interviewed were the first among their extended families to go to college. In these interviews, participants also revealed a host of personal challenges, including language barriers, depression, learning disabilities, and, in some cases, the effects and stress of pervasive violence and drug use in their communities. In other words, though the program selected “talented urban youth” for participation, the odds for having an effective-cum-successful experience were not always in the participant’s favor as he, she or they sought pathways to higher education and the more robust career and life paths earning university degrees tend to yield.

Critically examining Youth Design offers guidance about how designers and the design communities they affect (and are affected by) can promote social empowerment and personal transformation in urban youth. Youth Designers were offered financial, social, and educational opportunities often available within more affluent communities, sometimes located just outside their own. [21] The impact of these efforts can be observed in the near term by analyzing positive educational outcomes and in the long term by analyzing their empowering effects.

Could a program like Youth Design operate in ways that remake or reposition design itself as a socio-cultural, public policy and economic catalyst? While there is no easy answer, perhaps this question provides a lens that future programs similar to this should look through as they are imagined and instigated. Design-oriented youth education programs may help work to position given design communities to reclaim or expand the current meanings of contemporary terms such as “design thinking,” rescuing them from their far more common deployment within corporate-rooted initiatives. For example, some design and social sciences theorists have recently argued that, “unless design remakes itself, it will remain dominantly an unthinking ‘tool’ of defuturing.” [22] Grassroots design-oriented youth initiatives such as Youth Design provide insight into how a community of designers can reorient at least some of its core purposes toward the realization of more humanistic goals.

For over 14 years, Youth Design mobilized the Boston-area design community around the idea and actuation of empowering local urban youth. As designers build upon such efforts, pathways can develop for deeper community engagement — vis-à-vis questioning and redesigning equity, [23] improving human experiences,[ii] or exposing urban youth to the power of design in the public and “publics.” [24] In our interviews, Korn suggested that, “younger designers more deftly understand the role of experience in design.[jj] Indeed, opportunities for more designers to engage in social justice initiatives that lie at the intersection of empowerment and design may further instigate, in the words of Manzini, “new and sustainable ways of living and doing.” [25] With this in mind, urban youth who engage in such efforts and designers who lead such them may collectively help reorient the power of design as a defense against the all too often inequitable design of power.

References

- AIGA. “AIGA Designer 2025: Summary Document, “AIGA Design Educators Community (blog). Available at: https://educators.aiga.org/aiga-designer-2025/ (Accessed March 25, 2020).

- AIGA, “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” Available at: https://www.aiga.org/aiga/content/tools-and-resources/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-equity-inclusion/ (Accessed March 20, 2021).

- Balliro, B. “Access and Failure.” The Journal of Social Theory in Art Education, 35.1 (2015): Available at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jstae/vol35/iss1/2/ (Accessed January 1, 2019).

- Barbosa, A. in discussion with the author, October 2021.

- Boakye, A. and Procida, C. “What Does It Mean to ‘Empower’ Youth?,” Aspen Institute, 13 April, 2016. Available at: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/mean-empower-youth/ (Accessed May 18, 2022).

- Bothwell, R. O., “Foundation Funding of Grassroots Organizations.” COMM-ORG: The On-Line Conference on Community Organizing and Development, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. 2000.

- Carroll, Antionette. “Designing for a more equitable world.” TED Archive. YouTube. 17 January 2019. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z9XKBgdOrHU (Accessed January 3, 2021).

- Caceres, Y., in discussion with the author, October 2021.

- Davis, M., Hawley, P., McMullan, B., and Spilka, G, Design as a Catalyst for Learning. Alexandra, Virginia, U.S.A.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1997.

- designExplorr. “About designExplorr,” accessed March 1, 19, 2022, Available at: https://designexplorr.com/about/.

- Fitzgerald, Jay. “Dedicated to Design,” Boston Business Journal, 9 March, 2018. Available at: https://www.bizjournals.com/boston/news/2018/03/09/denise-korn-focuses-on-promoting-the-creative.html (Accessed July 26, 2018).

- Fry, T. and Nocek, A., eds. Design in Crisis: New Worlds, Philosophies and Practices. London, U.K. and New York, New York, U.S.A.: Routledge, 2021. p. 219.

- Ganci A. and Napier, eds., Dialogue: Proceedings of the AIGA Design Educators Community Conferences, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A.: Michigan Publishing, 2020.

- Gay, M. and Russell, J., “Neighboring schools, worlds apart,” The Boston Globe, 14 September, 2019. Available at: https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2019/09/14/neighboring-schools-worlds-apart/ytlIIcdbbO59i2CDK2qWOL/story.html (Accessed January 20, 2020).

- Korn, D. and Kane, Neil. 10 Who Mentor: Inspiring Insights from Creative Legends. Wilmington, Massachusetts, U.S.A.: 2010, p. 125.

- Korn, D., in discussion with the author, April 2018.

- Lord, J. and Hutchison, P. “The Process of Empowerment: Implications for Theory and Practice.” The Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 12.1 (1993): pg. 2. Available at: http://www.johnlord.net/web_documents/process_of_empowerment.pdf (Accessed January 2, 2021).

- Manzini, E. “Social Innovation and Design: Enabling, Replicating and Synergizing.” In The Social Design Reader, edited by E. Resnick, New York, New York, U.S.A.: Bloomsbury, 2019: p. 403.

- McMillan, S. “The Changing Face of Design,” Communication Arts, July/August, 2016.

- Passel, J., Cohn, D. and Lopez, M. “Hispanics Account for More than Half of Nation’s Growth in Past Decade, “Pew Research Center. 24 March 2011. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2011/03/24/hispanics-account-for-more-than-half-of-nations-growth-in-past-decade/ (Accessed January 10, 2021).

- Reid, K. in discussion with the author, August 2016.

- Reid, K. in discussion with the author, October 2021.

- Reid, T. in discussion with the author, October 2021.

- Sutton, S.E., Kemp, S.P., Gutiérrez, L., and Saegert, G., Urban Youth Programs in America. Seattle WA, USA: University of Washington/Ford Foundation, 2006.

- Victor, Marquis. “Transforming Community: The Power of Art.” Panel discussion at Merrimack College, North Andover, Massachusetts, U.S.A., April 2022.

- Walker, Jacinda N. “Design Journeys: Strategies for Increasing Diversity in Design Disciplines.” Master’s thesis, The Ohio State University, 2016.

- Williams, L. “The Co-Constitutive Nature of Neoliberalism, Design, and Racism.” Design and Culture, 11.1 (2019): p. 301.

Biography

Dan Vlahos is an Assistant Professor of Visual and Performing Arts at Merrimack College where directs the undergraduate Graphic Design Program. He is currently serving on the Board of Directors for AIGA Boston and on the Design Museum Everywhere Council. Vlahos’ interdisciplinary work in design, branding and dynamic media has been recognized by the AIGA, the One Club, Print and the Interactive Media Council. His clients include Harvard University, Duke University, Educators for Social Responsibility and the Industrial History Center. He received both an MFA and BFA from Massachusetts College of Art and Design. In 2020 Vlahos was named a Presidential Fellow by the Merrimack College Interdisciplinary Institute. vlahosd@merrimack.edu

- a

Lord and Hutchinson provide a detailed discourse on empowerment, power and powerlessness in their 1993 paper. See: Lord, J. and Hutchison, P. “The Process of Empowerment: Implications for Theory and Practice.” The Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 12.1 (1993): pg. 2. Online. Available at http://www.johnlord.net/web_documents/process_of_empowerment.pdf (Accessed January 2, 2021).

- b

In this case, “Urban” refers to the demographic concentration of minorities living in larger U.S. cities that are often marginalized from society due to race, income level, ethnicity, religious beliefs, lack of economic and educational opportunities, or some combination of these.

- c

See: learnXdesign, led by the New York Hall of Science; and Imagining America, currently based at UC Davis. More information about learndXdesign can be found by visiting https://learnxdesign.org/. (Accessed May 15, 2022). This organization’s efforts and programs should not be confused with those planned and facilitated by the Design Research Society (DRS), which has been operating academic conferences titled with this moniker since 2013.

- d

My use of “grassroots” here generally refers to organizations that are locally based and largely autonomous and rely upon volunteers, a small paid staff, or some combination of the two. See: Bothwell, R. O., “Foundation Funding of Grassroots Organizations,” COMM-ORG: The On-Line Conference on Community Organizing and Development, 20 September 2000. Online. Available at: https://comm-org.wisc.edu/papers2001/bothwell.htm (Accessed May 13, 2022).

- e

Such organizations include Elevated Thought in Lawrence, Massachusetts, U.S.A.; The Creative Reaction Lab in St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A., Artists for Humanity, also in Boston, the Summer Design Project, led by Design Museum Everywhere in Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A,.; The AIGA Link Program, in Seattle, Washington, U.S.A.,, and designExlplorr in Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A. to name but a few.

- f

This article leverages research led by the Center for Environment Education and Design Studies. See: Sutton, S.E., Kemp, S.P., Gutiérrez, L., and Saegert, G., “Urban Youth Programs in America,” Seattle Washington, U.S.A.: University of Washington/Ford Foundation, 15 April, 2006. Online. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/rchild/UrbanYouthinAmericaSummary.pdf (Accessed May 5, 2022).

- g

This line of research around Youth Design was first presented as part of a panel at the 2018 AIGA DEC [MAKE] Conference in Indianapolis, Indiana, (U.S.). Most attendees were unfamiliar with Youth Design prior to the conference presentation. See: Ganci A. and Napier, eds., Dialogue: Proceedings of the AIGA Design Educators Community Conferences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA: Michigan Publishing, 2020.

- h

- i

Denise Korn (founder of the AIGA-supported Youth Design organization), in discussion with the author, April 2018.

- j

In this context, “urban”refers to metropolitan areas with a population of at least 1 million for densely settled states, and 500,000 for sparsely settled states.

- k

AIGA Boston was a founding partner of Youth Design and supported the program by maintaining an ongoing partnership commitment to it.

- l

“Design” and/or “design community” are used here and throughout this paper as monikers that encapsulate graphic design, advertising, industrial design, architecture and fashion design.

- m

Massachusetts College of Art and Design supported the efforts of Youth Design with space, expertise and equipment.

- n

- o

The three college credits were awarded through the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. The support of college administration and the Department of Communication Design was instrumental in establishing processes and protocols for how these credits would be earned and documented.

- p

The author served as an instructor for this studio-based training component.

- q

The average annual stipend provided by Youth Design to the participants was $1,750. Youth Design raised these funds largely from corporate donors and grants.

- r

- s

Interviewers asked each candidate if they were planning on working a summer job, or if the candidate had other summer opportunities available to them (sports, clubs, guidance counselors etc.).

- t

Students were allowed to report information related to public assistance and need, but this remained optional.

- u

As is noted in a later section, Korn believed that Youth Design’s “platform” was focused largely on learning, experimenting, and expanding points of view.

- v

At The Massachusetts College of Arts and Design.

- w

According to the National Association of Schools of Art and Design (NASAD), in 2010, only 3.5% of communication design “majors” in the U.S. were Black, and only 4.2% were Hispanic or Latinx. In 2010 those identifying as Black and/or African American made up 13.6% of the U.S. population, while Hispanics accounted for 16.3%. See: Passel, J., Cohn, D. and Lopez, M. “Hispanics Account for More than Half of Nation’s Growth in Past Decade, “ Pew Research Center. 24 March 2011. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2011/03/24/hispanics-account-for-more-than-half-of-nations-growth-in-past-decade/ (Accessed 10 January 2021).

- x

- y

A digitized archive of materials from the Youth Design organization can be accessed by contacting AIGA Boston: info@boston.aiga.org

- z

- aa

Yamilet Caceres, in discussion with the author, October 2021.

- bb

In 2019 median homeowners in the U.S. had 40 times the household wealth of a renters, which equates to roughly $254,900 for the former compared to $6,270 for the latter. See: https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/scf20.pdf. (Accessed May 17, 2022).

- cc

Black Americans have the lowest rate of homeownership (47%) compared to other racial groups, with White Americans having a homeownership rate of 76%. See: https://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/files/currenthvspress.pdf. (Accessed May 16, 2022).

- dd

- ee

- ff

- gg

In June 2014, Tony Richards joined Youth Design as its first full-time Director, bringing years of experience working in community development and youth civic engagement, and with low-income youth.

- hh

- ii

Here intentionally use “human experience” over the all too commonly used term “user experience.” The word “experience” or “experiences” was used fifteen times in the AIGA Designer 2025 Summary Report. See: AIGA. “AIGA Designer 2025: Summary Document, “ AIGA Design Educators Community (blog). Available at: https://educators.aiga.org/aiga-designer-2025/ (Accessed 25 March 2020).

- jj

Marquis Victor, “Transforming Community: The Power of Art” (panel discussion, Merrimack College, North Andover, Massachusetts, U.S.A., April 5, 2022).

Sutton, S.E., Kemp, S.P., Gutiérrez, L., and Saegert, G., “Urban Youth Programs in America,” Seattle Washington, U.S.A.: University of Washington/Ford Foundation, 15 April, 2006. Online. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/rchild/UrbanYouthinAmericaSummary.pdf (Accessed May 5, 2022).

Boakye, A. & Procida, C. “What Does It Mean to ‘Empower’ Youth?,” Aspen Institute, 13 April, 2016. Online. Available at: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/mean-empower-youth/ (Accessed May 18, 2022).

Davis, M., Hawley, P., McMullan, B., and Spilka, G, Design as a Catalyst for Learning. Alexandra, VA, USA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1997.

AIGA, “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” Available at: https://www.aiga.org/aiga/content/tools-and-resources/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-equity-inclusion/ (Accessed 20 March 2021).

Balliro, B. “Access and Failure.” The Journal of Social Theory in Art Education, 35.1 (2015): Available at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jstae/vol35/iss1/2/ (Accessed 1 January 2019).

McMillan, S. “The Changing Face of Design,” Communication Arts, July/August (2016): p. 35.

Jacinda N. Walker, “Design Journeys: Strategies for Increasing Diversity in Design Disciplines” (master’s thesis, The Ohio State University, 2016), ii, http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1469162518. (Accessed May 19, 2022).

“About designExplorr,” designExplorr, accessed March 1, 19, 2022, Available at: https://designexplorr.com/about/. (Accessed May 19, 2022).

Marquis Victor, “Transforming Community: The Power of Art” (panel discussion, Merrimack College, North Andover, MA, April 5, 2022).

Fitzgerald, Jay. “Dedicated to Design,” Boston Business Journal, 9 March, 2018. Online. Available at: https://www.bizjournals.com/boston/news/2018/03/09/denise-korn-focuses-on-promoting-the-creative.html (Accessed 26 July 2018).

Korn, D. and Kane, Neil. 10 Who Mentor: Inspiring Insights from Creative Legends. Wilmington, MA, USA: 2010, p. 125.

See: Gay, M. and Russell, J., “Neighboring schools, worlds apart,” The Boston Globe, 14 September, 2019. Available at: https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2019/09/14/neighboring-schools-worlds-apart/ytlIIcdbbO59i2CDK2qWOL/story.html (Assessed January 20, 2020).

Fry, T. and Nocek, A., eds. Design in Crisis: New Worlds, Philosophies and Practices. London, U.K. and New York, New York, U.S.A.: Routledge, 2021. p. 219.

For more on this topic see: Carroll, Antionette. “Designing for a more equitable world.” TED Archive. YouTube. 17 January 2019. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z9XKBgdOrHU (Accessed 3 January 2021).

See: https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/design-studies/publics/ (Accessed May 18, 2022).

Manzini, E. “Social Innovation and Design: Enabling, Replicating and Synergizing.” In The Social Design Reader, edited by E. Resnick, p. 403. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury, 2019.