Supporting Student Mental Health in an information Design Class By Employing Approaches Derived From Positive Psychology

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This paper presents an overview of the design of an undergraduate-level information design class, where concepts from positive psychology were incorporated into the facilitation of the class to support the mental health of the students enrolled in it. Through a series of class projects centered around allowing these students to self-examine their individual mental states, their engagement with the class content helped them to increase their self-awareness about some of their specific mental health issues and provided them with a means to engage in self-diagnosis, and further suggested some strategies for self-care. The metacognitive learning offered by the facilitation of the class not only taught the students some of the fundamental knowledge and techniques for effectively meeting design challenges rooted in information design — which was and is the core purpose of this class —but also promoted the mental health literacy of the students who took it and increased their abilities and willingness to engage in sharing some of the insights they gained as they sought to mutually support each other. This paper critically discusses the construction of the class in detail, as well as the structure and final outcomes of the class projects that the students completed. The class was taught in the Department of Design at The Ohio State University, both before and during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, and was also adapted into another teaching format when it was applied within the structure of a week-long workshop before the COVID-19 outbreak. This case study contributes to critical thinking about a pedagogical approach for integrating the teaching of the core materials necessary to effectively operate an undergraduate information design course with strategies and tactics for supporting the mental health of the students enrolled in it.

Introduction

Today’s college students report being more stressed, anxious, depressed, and disconnected than any generation before them. [1] Based on the 2019 American Freshman National Norms [2] of students entering college, only 28.2 % of students reported above average physical and emotional health, 42.7 % reported feeling overwhelmed by all they had to do, 16.6 % reported feeling depressed, and 37.6 % reported feeling anxious frequently or occasionally. The timeliness and seriousness of these concerns have been recognized in many college campuses across the country. Although more concrete analysis of this data is still lacking as of this writing in the summer of 2021, it is reasonable to assume that the unprecedented COVID-19 lockdowns of colleges and univer-sities across the globe has only made the matter worse.

This paper discusses a new course exploration of an information design class taught at the undergraduate level within the Department of Design at The Ohio State University (OSU), within which investigations into select aspects of each student’s own states of mental health became an essential part of their learning experience. The course design was cross-disciplinary, as concepts and principles from positive psychology were introduced and integrated into the structure of the class. The primary goal of doing this was to raise the students’ self-awareness of their subjective well-being (SWB), and to further inspire their investigations of self-care strategies. Positive psychology is a branch of psychology that focuses on individual and societal well-being. More specifically, it involves the study of employing scientific understanding and effective interventions of the positive influences in an individual’s life that allows them, and communities they live and work within, to thrive. [3], [4] Tools and strategies developed by positive psychologists aim at helping people initiate and nurture positive feelings, positive thoughts, and positive behaviors. In the new course design for the section of information design being presented in this piece, we focused on studying students’ subjective well-being (SWB), which is a self-reported analysis of an individual’s general level of happiness and is further defined as “a person’s cognitive and affective evaluations of his or her life.” [5] (SWB and happiness will be used interchangeably in the rest of the article.) There is almost a ubiquitous agreement in psychology studies that happiness and well-being are important constructs to consider when evaluating individual or group-level indices of health and wellness.

In the field of information design and information visualization, visual computing methods are used to amplify human cognition with abstract information. [6] This abstract information includes both quantifiable data, such as numbers, text, geographic information, and qualifiable data, such as levels of well-being, and perceptions of factors that influence behavior. Students learn the process of transforming information into visual structures through its influence on human perception, behaviors, emotions, and the broader environmental and social effects of these. Like all design processes, the human- centered design approach [7], [8], [9] requires information designers to identify the real needs of real people who will use or be affected by experiencing a given designed outcome. [10] In the specific information design class being discussed in this case study, these essential information design concepts and techniques are taught and embedded with the students’ SWB. This is operationalized in ways that allow the students’ own well-being to become case studies for the design visualization topics that they explored as the class evolved. While learning the fundamental information design tools during the class, the students engaged in a series of class projects centered on their own SWB. Utilizing self-tracking data, they visualized and analyzed their SWB using the design tools and approaches they learned to deploy as the class progressed, and more importantly, to discover the patterns of thoughts, perceptions and behaviors that guided the evolution of their individual mental states. By focusing on happiness, and by following the principles espoused by positive psychology — these include but are not limited to positive deviance (“daring to go against the grain”), flourishing (as opposed to languishing), building on what people do well — the projects also guided the students to focus on their positive feelings, determine what exactly makes them happy, and what actions they could take to improve their SWB.

In the following discourse, we present the methodology and the detailed design of the class, as well as a description of the experience of teaching it in the Department of Design at OSU. The class has been taught as a one-semester undergraduate level course a total of four times at OSU: twice in-person in 2019 before the onset of the COVID-19 lockdown, and twice remotely in 2020 during the COVID-19 lockdown. Class enrollment averaged around 15 students. The unprecedented COVID-19 lockdown created different dynamics within the structure and the delivery of the class content, as the students discovered different patterns in their SWB that were directly related to their inabilities to engage in normal social interactivities due to the effects of the lockdown. The cross-disciplinary design of this class has also been adapted to another teaching format: it was applied to a week-long workshop held in-person in March 2019 (before the COVID-19 breakout) at Jiangnan University, China.

Methodology

The core of the course design was multimodal and consisted of (1) employing a “learning-by-doing” teaching approach that our Department of Design faculty have used to facilitate most of OSU’s Information Design classes in the past, (2) using positive psychology theory to influence SWB among students by focusing on helping them identify the source(s) of their happiness; and (3) analyzing the students’ SWB design visualizations as means to document and support their mental health needs.

Information design classes, like many graphic design or visual communication design studio classes, operationalize a learning-by-doing approach to encourage students enrolled in them to actively apply design theories and principles to real-life problems. [11] This learning method emphasizes the process of enabling learners to make sense of their experiences and to gain conceptual insights by engaging in hands-on activities. It has been proven effective in a wide variety of design learning environments. In contrast to this, studies from positive psychology have suggested that our SWB, or happiness, can be achieved and enhanced through allowing students to engage in activities related to enhancing their sensory awareness, social communication, gratitude practices, and cognitive reformation. [12] The goal of the new design of the class was to integrate primary ideas derived from positive psychology into how specific design tools and techniques were taught to improve the SWB of the students enrolled in it. This was accomplished by a series of class projects fueled by information design prompts that 1) aimed to help students elevate their self-awareness about addressing their mental health issues, 2) that guided them to think more critically about engaging in self-care strategies, 3) that promoted the sharing of feelings and ideas among the students to ensure mutual support, and that 4) instilled design thinking informed by interdisciplinary approaches into their work.

Self-awareness

The foundation of the class was based on understanding and effectively deploying the fundamental aspects of information design processes which consists of task analysis, data collection, and visual representation. [13], [14] In the new class design, we guided the students through learning these processes as we encouraged them to focus on issues that influenced their own SWB. At the beginning of the class, the students were asked to start to record their daily activities and mood indicators, which effectively served to help them create a diary for documenting each of their respective SWBs. As they continued to track and add entries to their SWB diaries, the students began to become more mindful of the daily evolution of their mental states. Each student was then asked to complete the design tasks necessary to discover and identify visual representations of the pattens and trends from their SWB diary, by using the information design tools taught in the class. These tasks guided the students to develop a much deeper level of self-understanding of their states of mind. A healthy sense of self-awareness, along with moments of reflection, are crucial skills to the design profession. The design tasks thus helped the students to develop, as designers, an accurate sense of their strengths and limitations, which are important for their career growth.

Self-care

There is a strong link between self-awareness and self-care [15] because effective self-care strategies are based on self-understanding. As the students applied the core design principles and visualization techniques to their SWB data, they discovered patterns, trends, and outliers related to their happiness. Using positive psychology theory, the students were advised to focus on the positive side of SWB, establish causality between daily activities, and design optimal visual representations. By doing so, the students developed a stronger sense of “what to do” and “what not to do” to improve their personal states of happiness. While some of the findings offered here are rooted in common sense, the unusual situation created by COVID-19 helped the students to discover new routines to improve their mental health. Examples and case reports of instances of this are discussed in the latter part of this article (see the sections on “Class project 2” and “Class project 3”).

Community Sharing

Being a part of a community can have a positive effect on one’s mental health and emotional well-being. Community involvement provides a sense of belonging and social connectedness. [16] Design classes are traditionally built upon the culture of sharing and critiquing, usually in the form of exchanging ideas and feedbacks in a group. Since our new class revolves around a common theme of SWB, this creates a much stronger bond among the students in the class. Not only do the students exchange ideas on the technical aspects of their work, but they also engage in discussions to share their experiences and offer mutual support. This became especially evident when the class was taught in 2020 during the unprecedented COVID-19 lockdown. While the sharing was mostly confined to classrooms during the teaching of the course, both in-person before the lockdown and remotely online during the lockdown, it also reached a larger community during its adaptation of the week-long workshop in 2019 when the students from different parts of the campus became part of the active participants of the class projects.

Interdisciplinary Design Thinking

In addition to the traditional theory and tools for Information Design, the class also teaches the students the skills of synthesizing thinking across disciplines. The design projects in the class provided a platform for the students to create visual structures that connected and resonated with their feelings, and further enriched their learning experiences. However, this information design class was not a class on “mental health,” which is a topic beyond the design discipline. Rather, the new class design aimed at integrating the related concepts from positive psychology into design approaches and techniques to promote mental health support and awareness among the students enrolled in it. The strategies and skills included in positive psychology interventions guided the students through processes that challenged them to critically examine the same things from different perspectives.

Class Structure and Practice Examples

The Information Design class is a semester-long class taught in the Depart-ment of Design at OSU. The class is structured into a series of projects that are directly related to the students’ SWB. These class projects will now be described in more detail.

Class Project 1: “In the Present”

The purpose of this project was to engage the students in collecting and then analyzing data about their daily activities. A key emphasis of this process was the principle of “no judgement:” students were asked to avoid making critical comments about each other's daily activities, or the motivations for them. This involved the students being advised to faithfully record their daily activities and to keep a record of how they spent their daily hours for a duration of one week. The project was open-ended in nature, as the students could choose any part of their lives to document. Students were encouraged to include as many detailed data entries as possible. Once the students collected and organized their raw data, they mapped the data into visual formats by utilizing various information design concepts and techniques that were taught in the class. The design skills the students acquired helped them practice using graphical elements (points, lines, areas, surfaces, or volumes) and then deploying these according to their understandings of graphical properties (positions, colors, or sizes). [17], [18]

Two representative examples are depicted below in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 was created by a third-year undergraduate student majoring in data analytics named Jeremy Huang. He chose to display the distribution of his different activities on a daily 24-hour timeline. The data are encoded with colors to show the categories of the activities he engaged in, with lengths and area sizes depicted to indicate the amount of time spent on the timeline and the daily average data depicted in the treemap at the bottom of the page. Figure 2 is the work of another third-year undergraduate data analytics student named Andrew Diederich, who attended the class in 2020 virtually during the COVID-19 lockdown. In this work, Andrew used pictograms to visually communicate the activities of napping and the types of transportation he used. Colors are employed to visually encode the categorical data. A pie chart is used to reveal the comparison of time. A bar chart depicts the comparison of the number of miles he traveled per day. Andrew was surprised to see his daily phone usage consumed more than 50 % of his awake time — a direct consequence of the COVID-19 lockdown. The lack of social activities during the pandemic lockdown also resulted in an increased amount of sleep hours and naps during the daytime (Figure 2). This project helped the students who undertook it better understand the variety of factors that affected their daily routines and raised their awareness of the changes that were occuring within each of their state of minds, particularly during the pandemic. The practice of documenting every detail in life also helped the students to become more aware of their mindsets, activities, and the effects that surrounding environments had on these (self-awareness cultivation).

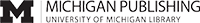

Class Project 2: Gratitude Tracking Diagram

While the first project in this case study was based on the act of fostering nonjudgmental awareness, the second project was designed to invite the students who undertook it to intentionally sharpen their attentions on the positive aspects of their lives (i.e., the principles that form the foundations of positive psychology). The students were asked to keep a “daily gratitude journal” for 30 days to (1) record three things or moments that brought them joy; (2) categorize entries they recorded by using certain common criteria; and (3) use specific methods for engaging in visual design processes to visually depict their entries and to help them establish meaningful connections between them. Cultivating gratitude in everyday life is one of the keys to increasing personal happiness [19] because gratitude helps people to focus on what they have, as opposed to what they lack. Upon completing the project, the students involved in it had cultivated a much deeper understanding of their personal states of mind and sources of gratitude.

As a representative example, Figure 3 depicts the work by third-year undergraduate, visual communication design student Seonggyeong Hong, who categorized her gratitude journal data by using the Maslow’s hierarchy of needs pyramid (Figure 3) to guide the design of her oganizational structure. The data that constituted Seongyeong’s gratitude journal were then visually encoded with colors, locations, the relative sizes of the pie slices she incorporated to communicate quantities, as well as line styles and arrow directions. Upon finishing the work, Seonggyeong was surprised to discover that the top contribution to her gratefulness had emerged from the category of physiological needs, ahead of love and belonging. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some students also used the identification and description of daily affirmations and aspirations to motivate themselves at the beginning of every day to help them make positive changes within their lives.

Figure 4 is the work of Sara Torchia, another third-year undergraduate, visual communication design student. Upon categorizing the entries from her gratitude journal into daily affirmation, aspiration, and reflection, Sararepresented them with pictograms, visualizing them in a circular pattern corresponding to weekdays, and made connections with her gratitude levels and self-reflections at the end of each day. The weekly data visualization indicated that, to Sara, “family and friends” were what she felt most grateful for, and “being mindful about myself” was what she reminded herself most often everyday (Figure 4).

Class Project 3: Visual Guide to Happiness

The final project of the sequence aimed at identifying practices and guidelines to enable, support, and inspire the students in their personal pursuits of well-being (i.e., the operation of self-care strategies). Upon reflecting on the patterns and trends revealed from their engagements in the previous projects, the students discovered data-based evidence that could meet or support their personal mental health goals, which involved helping them to reach a “happier” state of mind. They were able to identify and rank the factors that were most important regarding helping them to achieve their stated goals, and were then able to create visual representations that depicted how to reach this goal. Various visualization tools and techniques that they learned during their enrollments in this class, such as utilizing process charts and deploying icons, colors, and typography, were used in the creation of their final information design products to visualize their individual design processes in ways that visually com municated how they could reach (or did reach) their “happier” states of mind.

Figure 5 depicts the work of Nicole Lorig, a fourth-year undergraduate majoring in animal science, who created a “Happy-ology guide” based on an analysis of her activity data and information gleaned from her gratitude journal. Figure 6 is the work of Thomas Ferguson, a fourth-year undergraduate student studying communications, who analyzed the connection between the things that stressed him the most, and the mechanisms he used to cope with them. Thomas eventually used pictograms and a flowchart to map these connections and to ultimately visualize the activities that most effectively allowed him to cope with his stressors (Figure 6).

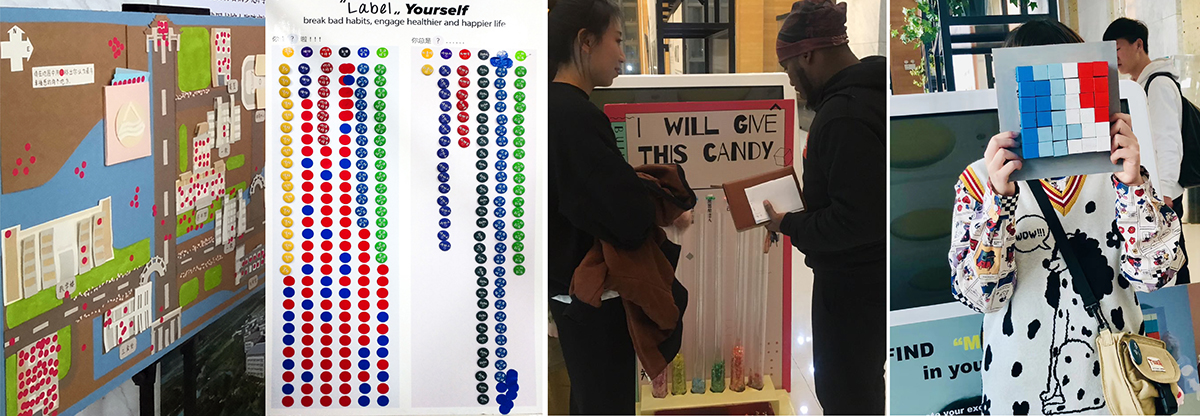

Adaptating Positive Psychology Approaches Into Different Educational Settings: a Workshop Example

An idea for incorporating positive psychology into teaching processes that can be operated effectively in educational settings other than the standard undergraduate information design classrooms is articulated in this sub-section of this case study. It consisted of a weeklong workshop that was facilitated in-person at Jiangnan University in China in 2019. The objective of this workshop was to introduce the process of data collection, data analysis, and data visualization to undergraduate students majoring in interactive design there. In this pre-Covid workshop, the participating students were organized into five teams, each of which was assigned to examine and incorporate one pillar of the PERMA theory of well-being, as defined by Martin Seligman, [20] into their working processes. (PERMA = Positive Emotions, Engagement, Positive Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment.) They were challenged to utilize these to guide their design decision-making as they completed various analytical tasks. The resulting installations were intended to satisfy three primary criteria: first, to serve the purpose of collecting data from the public, second, to implement the PERMA theory of well-being, and third, to help a given viewing audience effectively interpret information and discern hidden patterns that were threaded through the collected data. The physical data collection models were constructed with various easy-to-obtain materials such as paper, wood, metal, and food. The visual representations of the data that the students gathered included two-dimensional charting and diagramming forms such as heatmaps, bar charts, treemaps and scatter graphs (See Figure 7 and 8). For example, the Accomplishment Team used paper boards to create a 4-year college timeline that measured approximately 8x 3 feet (.9 m x 2.5 m; Figure 8). Audiences were provided color-coded dot stickers to mark their “reached” and “planned” goals on this timeline. The colors of the dots represented various types of individual goals, including scholarship, volunteer work, becoming a student organization leader, finding an internship, finding love and / or friendship, implementing self-image improvements, etc. The size of the dots represents the sense of accomplishment associated with the goals, from weak (small) to strong (big). The students then analyzed the data, conceptualized their visualization approach, and built non-digital interactive installations that reflected the happiness strategies derived from engaging in analyses guided by approaches rooted in positive psychology.

User experience evaluations were also included in these processes. By operating user surveys, the design students involved in this project assessed the usability of the physical manifestations of their information design devices based on the results of their data analyses, which included user interest, user engagement, willingness to explore, information communication, gaining knowledge and insights, and inspiring actions. A larger-than-expected turnout (approximately 150 students during the spring session) among the students on campus who chose to share personal information indicated that there was a strong interest on that campus in participating in public projects like this. Survey results indicated that the perception of the colorful display of effectively visualized data combined with curiosity about the outcomes of the data that was being analyzed were two major reasons these students were attracted to this work. Many participants also commented on the positive feelings triggered by engaging in and witnessing the accumulation of data entries from their campus peers (community sharing). These positive feelings were mainly associated with their sense of belonging and validation. As their participation in this workshop progressed, these students who participated in it realized that they were not in experiencing powerful, emotionally charged feelings and in having to confront a wide variety of personal struggles. The visual display of the data points also helped the students self-reflect on their mental health needs and their wellness goals.

Discussion

Information literacy, posited here as the ability to evaluate, interpret, and effectively visualize information, is both a critical skill and a basis for knowledge that designers working with technology and on interdisciplinary teams must possess and be able to utilize to good effect. Good designers know how to harness data to positively influence design decision-making processes, and to effectively inform how they plan for and engage in these. The design projects presented in this case study have been offered as a measn to describe and understand (what mental health issues are, what coping strategies are), model and predict (what a happier and more fulfilling life can be) and share and communicate. The projects also serve the purpose of facilitating information design education, with a focus on teaching students learning to do it how (and why) to use data to tell a meaningful story that resonates both intellectually and emotionally with a particular viewing audience. Moreover, these students must also learn how to conceive of data analysis and visualization as an opportunity to build a stronger self-empowerment mentality and cultivate a supportive community of empathy to bolster personal and collective mental health. While it is critical that institutions — both professional and academic — provide viable resources to support mental health, it is also important for the design students and professionals that are integral to their operations to care enough about it to ensure that what they design can effectively address these needs.

The prospects and benefits that accrue from incorporating mental health knowledge into design classes are promising. As the instructor of the information design class described throughout this case study, the author noticed more-than-usual enthusiasm from the enrolled students when they performed the class projects because the projects allowed students to examine and visually communicate their own feelings and mental states. The mutual support the students provided to each other was also warm, sometimes even touching, especially during the COVID-19 lockdown. The course in its current form focuses on introducing the theory and methods for engaging in information design, as it is an undergraduate-level design class. There are clear boundaries that guide the process of exploring how to integrate psychology-related subjects in a visual communication design class. Design instructors should not try to “teach psychology,” or actively intervene with regard to addressing the mental health issues of their students because we lack the professional training and qualification necessary to do this. Available resources for supporting students’ mental health were and are provided as essential components within the array of written materials provided to them to support the teaching of the course at its outset, as were and are a generalized amalgam of mental health coping techniques. Obviously, more could have been and can still be accomplished to further support the mental health of students enrolled in visual communication courses and curricula. Doing this should involve campus personnel or professional who possess expertise in behavioral psychology. The author is using what she learned experientially from having taught this course, combined with data gleaned from her students’ feedback about it, to guide the progress of her ongoing collaboration with a colleague from OSU’s Department of Psychology to revise and improve the learning experiences facilitated within the information design course. Their shared goal is to further improve the course by strengthening its positive psychology component and by providing more active mental health support for the students enrolled in it.

Conclusion

The design of the information design class discussed in this paper demonstrates that it is possible, and personally empowering, to incorporate ideas and theory from a discipline outside design — in this case, (broadly) psychology and (more specifically) positive psychology, to make the outcomes of individual students’ information design learning processes more positively impactful for themselves. And their audiences. By employing concepts derived from positive psychology, the metacognitive learning approaches developed during the operation of this class illustrates the potential of using data-driven information design and information visualization as an empowerment tool to support the mental health of the students enrolled in it. As both high mental health literacy and a strong sense of self-awareness have been associated with increased mental well-being, [21] this study specifically explored opportunities for integrating mental health-based knowledge into an existing set of information design classes. Another key takeaway from facilitating these kinds of learning experiences is that embedding psychology-based mental health knowledge into an information design class does not require overhauling the entirety of the teaching approach currently being used to guide the learning experiences of those enrolled in it. Instead, it requires the adaptation and reshaping of the class structure and content to more be more effectively synthesized with the mental states of its students, and to support those students academically, psychologically, and socially. The same principle that informs this cross-disciplinary course design can potentially be applied to other important social topics that designed inquiries and outcomes could positively affect and will be explored in the future.

Biography

Yvette Shen is an Assistant Professor of Visual Communication Design in the Department of Design at The Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, USA. Before joining academia, she worked as an interactive designer who closely collaborated with people in professional industries such as healthcare, automotive supply and information, the visual arts, entertainment, and in non-profit organizations. Her current creative and research expertise mainly lies in the field of information design and information visualization. In particular, she is interested in interrogating how engaging in design processes can help people from many walks of life gain better understandings of and about complex information, and, in so doing, increase their interest in learning even more. She is also keenly interested in examining how the practice of visualization combined with user experience research might empower people to enact more positive behaviors and experience more positive emotions. [email protected]

References

- Auerbach, R.P. et al. “WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127.7 (2018): pgs. 623–638.

- Beasley, L., Kiser, R., & Hoffman, S. “Mental health literacy, self-efficacy, and stigma among college students”. In Social Work in Mental Health, 18.6 (2020): pgs. 634–650.

- Bertin, J. Semiology of graphics: diagrams, networks, maps.Redlands, CA, USA: Esri Press, 1984.

- Bruce, B. C., & Bloch, N. Learning by Doing. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning (pp. 1821–1824). New York, NY, USA:

- Buchanan, R. Human Dignity and Human Rights: Thoughts on the Principles of Human-Centered Design. 2001. Online availble at: https://proyectaryproducir.com.ar/public_html/Seminarios_Posgrado/Material_de_referencia/Human Dignity and Rights - Human Centered Design.pdf (Accessed april 2, 2021).

- Card, S. K., & Mackinlay, J. The Structure of the Information Visualization Design Space. 1997. Online. (Accessed April 2, 2021).

- Card, S. K., Mackinlay, J. D., & Shneiderman, B. “Information visualization: using vision to think,” In Readings in information visualization: using vision to think, Burlington, MA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann, 1999. https://bit.ly/3rxHQZ6

- Cooley, M. “Human-Centered Design,” In R. Jacobson (Ed.), Information Design: pgs. 59–81. Cambridge, MA, USA MIT Press, 1999.

- Diener, E. “Subjective well-being: The Science of Happiness and a Proposal for a National Index,” in American Psychologist 55.1 (2000): pgs. 34-43.

- IDEO.org. The Field Guide to Human-centered Design. 2015. Online. Available at https://www.designkit.org/resources/1 (Accessed April 2, 2021).

- Kard, S. T., Mackinlay, J. D., & Shneiderman, B. Readings in Information Visualization, Using vision to think, Burlington, MA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann, 1993.

- Michalski, C. A., Diemert, L. M., Helliwell, J. F., Goel, V., & Rosella, L. C. “Relationship between sense of community belonging and self-rated health across life stages.” SSM - Population Health, 12, 100676 (2020).

- Pontis, S. & Babwahsingh, M. “Improving information design practice”. Information Design Journal, 22.3, (2017): pgs. 249–265.

- Richards, K., Campenni, C., & Muse-Burke, J. “Self-care and Well-being in Mental Health Professionals: The Mediating Effects of Self-awareness and Mindfulness” Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 32.3, (2010): pgs: 247–264.

- Schueller, S. M. & Parks, A. C. “The science of self-help: Translating positive psychology research into increased individual happiness”. European Psychologist, 19.2 (2014): pgs. 145–155.

- Seligman, M. E. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY, USA: Free Press, 2011.

- Seligman, M. E. “Positive Health,” in Applied Psychology 57 (2008): (SUPPL. 1): pgs. 3–18.

- Seligman, M. E. & Csikszentmihalyi, M. “Positive Psychology: An Introduction,” in American Psychologist, 55.1 (2000): pgs. 5–14.

- Shneiderman, B. “The Eyes Have It: A Task by Data Type Taxonomy for Information Visualizations” in The Craft of Information Visualization, pgs. 364–371. Waltham, MA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann, an imprint of Elsevier, 2003.

- Stolzenberg et al. “The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2019,” HERI UCLA, June, 2020. Online. Available at: (https://www.heri.ucla.edu/monographs/TheAmericanFreshman2019.pdf Accessed April 20, 2021).

- Watkins, P. C., Mclaughlin, T. & Parker, J. P. “Gratitude and Subjective Well-Being: Cultivating Gratitude for a Harvest of Happiness.” In Scientific Concepts Behind Happiness, Kindness, and Empathy in Contemporary Society. edited by Nava R. Silton, pgs. 20-42. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global, 2019.

Notes

Auerbach, R.P. et al. “WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127.7 (2018): pgs. 623–638.

Stolzenberg et al. “The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2019,” HERI UCLA, June 2020. Online. Available at: https://www.heri.ucla.edu/monographs/TheAmericanFreshman2019.pdf (Accessed April 20, 2021)

Seligman, M. E. & Csikszentmihalyi, M. “Positive Psychology: An Introduction,” in American Psychologist, 55.1 (2000): pgs. 5–14.

Seligman, M. E. “Positive Health,” in Applied Psychology 57 (2008): (SUPPL. 1): pgs. 3–18.

Diener, E. “Subjective well-being: The Science of Happiness and a Proposal for a National Index,” in American Psychologist 55.1 (2000): pgs. 34-43.

Card, S. K., & Mackinlay, J. The Structure of the Information Visualization Design Space. 1997. Online. https://bit.ly/3rxHQZ6 (Accessed April 2, 2021).

Buchanan, R. Human Dignity and Human Rights: Thoughts on the Principles of Human-Centered Design. 2001. Online availble at: https://proyectaryproducir.com.ar/public_html/Seminarios_Posgrado/Material_de_referencia/Human Dignity and Rights - Human Centered Design.pdf (Accessed April 2, 2021).

Cooley, M. “Human-Centered Design,” In R. Jacobson (Ed.), Information Design: pgs. 59–81. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 1999.

IDEO.org. The Field Guide to Human-centered Design. 2015. Online. Available at https://www.designkit.org/resources/1 (Accessed April 2, 2021).

Pontis, S. & Babwahsingh, M. “Improving information design practice”. Information Design Journal, 22.3, (2017): pgs. 249–265.

Bruce, B. C. & Bloch, N. Learning by Doing. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning (pgs. 1821–1824). New York, NY, USA: Springer US, 2012.

chueller, S. M. & Parks, A. C. “The science of self-help: Translating positive psychology research into increased individual happiness”. European Psychologist, 19.2 (2014): pgs. 145–155.

Kard, S. T., Mackinlay, J. D., & Shneiderman, B. Readings in Information Visualization, Using vision to think, Burlington, MA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann, 1993.

Shneiderman, B. “The Eyes Have It: A Task by Data Type Taxonomy for Information Visualizations” in The Craft of Information Visualization, pgs. 364–371. Waltham, MA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann, an imprint of Elsevier, 2003.

Richards, K., Campenni, C., & Muse-Burke, J. “Self-care and Well-being in Mental Health Professionals: The Mediating Effects of Self-awareness and Mindfulness” Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 32.3, (2010): pgs: 247–264.

Michalski, C. A., Diemert, L. M., Helliwell, J. F., Goel, V., & Rosella, L. C. “Relationship between sense of community belonging and self-rated health across life stages.” SSM - Population Health, 12, 100676 (2020).

Bertin, J. Semiology of graphics: diagrams, networks, maps. Redlands, CA, USA: Esri Press, 1984.

Card, S. K. & Mackinlay, J. The Structure of the Information Visualization Design Space. 1997. Online. https://bit.ly/3rxHQZ6 (Accessed April 2, 2021).

Watkins, P. C., Mclaughlin, T., & Parker, J. P. “Gratitude and Subjective Well-Being: Cultivating Gratitude for a Harvest of Happiness.” In Scientific Concepts Behind Happiness, Kindness, and Empathy in Contemporary Society. edited by Nava R. Silton, pgs. 20-42. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global, 2019.

Seligman, M. E. Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY:, USA Free Press, 2011.

Beasley, L., Kiser, R., & Hoffman, S. “Mental health literacy, self-efficacy, and stigma among college students”. In Social Work in Mental Health, 18.6 (2020): pgs. 634–650.