Examining the Influence of Positionality on the Facilitation of Design Processes

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Racism Untaught is an applied research framework co-developed a by Terresa Moses and Lisa Elzey Mercer — the co-authors of this piece — as a toolkit to help participants in co-participatory workshops create anti-racist approaches to designing that they can they deploy in academic, industry, and community settings in the U.S. and other nations around the world. Before instructing participants regarding how (and why) the Racism Untaught framework and the design interventions it yields can be used effectively, it is important for the individual designers and design teams participating in these workshops to understand their positionality in the context of racism, sexism, ableism, and other forms of oppression. (Design teams in these workshops can be comprised of teams of designers and a wide variety of stakeholders that include of six or seven individuals.) In the context of race, positionality refers to the social identities constructed by the dominant culture in a given society that shape how we understand, perpetuate, and uphold the intersectional systems of oppression that shape the everyday lives of those who identify as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. Racism is the conscious or subconscious belief and/or action (or sets of these) that supports the social construct of race as the primary determinant of human capacities, coupled with the belief that the most predominant race in a given society is inherently superior.

This article investigates the ways in which users of the Racism Untaught toolkit can construct knowledge in workshop settings about 1) how their predetermined social identities were and are created and perpetuated by the numerous factors that constitute the culture within which they live, and 2) how these identities then affect the way individuals engage in design processes that can evolve within their respective communities. This article will focus on describing the onboarding processes necessary to effectively implement the operation of the Racism Untaught toolkit in a workshop setting, as well as the activities rooted in examinations of social identity that the authors have implemented in specific situations to help prepare toolkit users to engage in open conversations about race, racism, and racialized design. One of the primary goals of this undertaking is and has been to sensitize diverse populations in particular communities about the often biased and illegal treatment some individuals and groups in those communities experience based on how they are perceived racially. The fundamental question that guided our analysis of the operation of the Racism Untaught toolkit during more than a dozen workshops over the course of over a year was, “How does the knowledge or awareness of someone’s social identity indicate or express his, her or their perception and understanding of this, and, as such, affect the ways he, she or they plan and then engages in (or does not engage in) given design decision-making processes?”

Introduction

We created the Racism Untaught toolkit to transform design processes by creating design interventions that could function within them that accommodate and, further, promote the facilitation of anti-racist thinking and creating. As we undertook the iterative process necessary to create the framework that would guide how Racism Untaught could be successfully operated in workshop settings, we became keenly aware of a factor that would be crucial to its efficacy. Specifically, we learned how important it was to immerse users of the toolkit in an onboarding process that would increase their understandings of how their positionality could affect the dynamics of any design team of which they were a part, as well as the roles they could play in advocating for anti-racist design decision-making. Understanding their own positionality against and within the context of racism and racist ideologies can help designers unlearn how we operationalize design to perpetuate and bolster systems of oppression that shape the everyday lives of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) [1] around the world.

The recognition of positionality is a lifelong process of conscious knowledge cultivation and construction that entails attempting to understand privilege, power, and marginalization. The social identities that an individual holds are contextually framed, meaning that the space and time within which he, she, or they present themselves has a significant impact on how they are perceived and how they perceive others, as well as why these perceptions exist as they do in particular societies and communities. The way these social identities are contextualized also largely determines who holds and wields power within them. We have come to understand the dominant cultural norm in the United States as one within which values, language, and behavioral standards are imposed on subordinate cultures through economic or political power. [2] As Margaret T. Hicken of the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research and her colleagues explain, “Racism does not require explicit intent or personal dislike on the part of its dominant actors. Rather, it is woven into our social structure and institutions, allowing for unequal life experiences and chances based on the socially constructed racial group membership categories.” [3] In the United States, these roles within particular social identity groups are — specifically — white, male, cisgender, Christian, and English-speaking, all of which are embodiments of dominant social identities [4] that have long held and continue to hold and wield power and privilege across this country. As early as 1970, Brazilian educator and advocate for critical pedagogy Paulo Freire emphasized the absoluteness of this power:

“In cultural invasion (as in all the modalities of antidialogical action), the invaders are the authors of, and actors, in the process; those they invade are the objects. The invaders mold; those they invade are molded. The invaders choose; those they invade follow that choice — or are expected to follow it. The invaders act; those they invade have only the illusion of acting, through the action of the invaders.” [5]

Throughout this article, we will:

- explore how so much of American history (and that of other colonized areas of the world) has been intentionally crafted to perpetuate the biases and the binary foundations, or systems, necessary to keep the dominant culture that operates within it in power (for further explication of this idea, please read the paragraph that appears immediately underneath this number list),

- investigate how an individual's own positionality is shaped and sustained by that history,

- discuss the social categories within which an individual exists, and within which he, she or they are perceived to exist, in a given society,

- acknowledge ways to create an equitable and vulnerable space within which diverse individuals and population groups can thrive, and

- analyze how the awareness of an individual’s positionality, and the creation of the aforementioned equitable and vulnerable spaces, can assist users of the Racism Untaught toolkit to successfully engage in the creation and effective operation of anti-racist design approaches.

In the context of this discourse, binary foundations, or systems, may be described by this definition offered by women’s and gender studies scholars Milian Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston and Sonny Nordmarken:

“Black and white. Masculine and feminine. Rich and poor. Straight and gay. Able-bodied and disabled. Binaries are social constructs composed of two parts that are framed as absolute and unchanging opposites. Binary systems reflect the integration of these oppositional ideas into our culture. This results in an exaggeration of differences between social groups until they seem to have nothing in common.” [6]

A Brief Description of the Historical Context That Shaped the Development of the Racism Untaught Toolkit

Most of history, which is inextricably linked to those who have had the power to shape it, conveys that much as the disabled body is the subject of disability, [7] so too is the Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color’s body the subject of racism. The ideas and ideologies that have shaped the dominant cultures in our societies in the world were intentionally created and have been perpetuated and normalized by those in power to keep themselves in power. Globally, colonial settlers the world over used the writing of history to craft historical narratives about the past that gave certain identities more power or privilege than others (that is, White, usually Catholic or Protestant, men).

These historical narratives, which have long functioned in so-called western culture to strip power and agency from communities that were and are not constituted primarily of these people, were historically perpetuated by many academic fields. This was particularly true across the disciplines that comprise the natural sciences, which dealt (and still deal) with studies guided by disciplines such as chemistry, biology, and geology. These were considered by many who practiced them or used their approaches to guide social and public policy decision-making to be “value-free.” [8] As we have come to learn since the 1960s (at least in the U.S.), the application of knowledge and understandings derived from the natural sciences to shape a wide variety of value systems in societies around the world has been anything but value-free. “Thus,” as historians Joyce Appleby, Lynn Hunt and Margaret Jacob opined in 1995 in their historiographical text Telling the Truth About History, “Understanding the challenge to truth in an age in full revolt against inherited certainties means going back in time to discover how and when science became an absolute model for all knowledge in the West.” [9] The natural sciences had played and still play a pivotal role in crafting and sustaining these narratives and tend to be supported by many mass media organizations, which often pay “scientists” to lie to the public in hopes that “the masses” will predominantly strive toward sustaining their beliefs within these structured normalcies rather than away from them. Questioning these narratives is and has also largely been discouraged.

One prevalent example of this kind of deception is exemplified by the development of the body mass index (BMI), which, as Margaret Hicken claims was, “designed to examine the biological, social, and environmental correlates of adult physical and mental health ... . The inequalities in obesity, particularly those that proxy visceral adiposity [having unhealthy levels of fatty tissue in the body], may then result in a cascade of health, social, and economic consequences that burden non-White adults with decreased life chances compared to White adults.” [10] The BMI’s “racist roots” and “the way it furthers the oppression of and discrimination against” [11] BIPOC is designed to uphold the racialized design of Eurocentric beauty standards and norms. This false sense of normalcy, which disability studies specialist Lennard J. Davis argues, “has always existed,” is socially ingrained in us, creating a toxic binary — between the ideal and non-ideal, the normal and the abnormal — which is socially, culturally, and physiologically dangerous to billions of people. This result of the sustenance of this toxic binary has deprived millions of communities across the globe of their basic human rights because of the unattainable standard of normalcy that has been socially constructed to make most of us feel as though we will never be able to look good enough without being perceived as someone who can showcase the latest lifestyle trend, with regard to the issue of BMI, the mass- and now social-media-approved ‘ideal’ body type and weight.” [12] The toxicity of the binary relationship between “desirable BMI” and “undesirable BMI” is a carefully crafted, intentionally designed “invention” to create a broadly acceptable and positively aspirational social norm and, in opposition to it, the “other,” through the carefully calculated retelling of past events.

The power held in the pen of the historian can completely erase the nuances and truths that constitute almost anyone’s past, and the ways that these contribute to how we perceive ourselves and others in our current societally framed realities. As the creators of the Racism Untaught toolkit, we sought to emphasize the power of storytelling to alter and overcome the effects of warping or erasing these socio-culturally rooted nuances and truths. Considering this, we invited over 300 participants (who were from diverse population groups in the U.S. and abroad) into the workshops — we have facilitated 13 of these since early 2020 — within which the toolkit was used to carefully consider three questions:

- Who gets to author particular stories about their histories and historiographies, and from which perspectives are these stories told?

- Who benefits when these stories are told from these perspectives?

- Who is missing from these stories when they are offered from these perspectives, and why are they “not there?”

“Those who commit the murders write the reports ... . The victims were black, and the reports are written to make it appear that the helpless creatures deserved the fate which overtook them.”— American investigative journalist, educator, and early civil rights leader Ida B. Wells, as part of an address she gave to the Women’s Era Club in 1893.

Interrogating How and Why “The Binary” Affects Social, Cultural and Political Perceptions

It is also important to understand that social, cultural, and political power and privilege — and the lack of these in given societies — are not inherently binary. Rather, it has become increasingly easy for those in power to use digitally facilitated communications systems to severely limit what could be a wide variety of social, cultural, political, economic, ethical, and values-based metrics for guiding our perceptions of ourselves and each other. This results in individuals and population groups around the world being denied opportunities to be per-ceived, and to perceive themselves, as possessing unique and richly nuanced personal and societal identities. When all of the identifiers that make us not only different, but socio-culturally relevant and authentic because we are different, are erased, we force ourselves to live in incredibly one-dimensional, static situations. In turn, this gravely stifles our abilities to envision futures that improve rather than inhibit, that facilitate rather than suppress.

Myopically crafted history that attempts to erase what a given society has identified and framed as non-ideal races, genders, sexualities, abilities, etc. from its past to guide its present retains a status quo that is both toxic and willfully ignorant. If these negative limitations are to be overcome, it is imperative to recognize the diverse nuances with which historically formed and framed identities are imbued, and this tends to go against what so many who have been educated in school settings across the U.S. (and many of the other so-called G20 nations in the word) have been taught. As a system to guide societal organization, the binary is a colonial, purist, and white supremacist [13] concept that does not allow room for depth, distinction, or gray areas (the lack of which are exemplified in the binary between “good” and “evil”). This hinders our willingness and ability to fully, or even nominally, understand so many of the societal complexities within which people living around the world must live their daily lives. To unpack our own positionality, we stress that all people must bring their full selves to the table, which must include all of the components, or “parts,” that may perpetuate systems of oppression, along with all of the parts that are striving for justice.

“It seems to me that the binary opposition that is so much embedded in Western thought and language makes it nearly impossible to project a complex response.” — bell hooks, American author and Professor, known for her writings that interrogate the intersectionality of race, capitalism and gender [14]

This inability to express social complexities is what Nigerian American author and feminist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie refers to as “The Danger of a Single Story.” [15] She warns that single stories produce and sustain limited and limiting stereotypes about what people are and what they have the potential to become. All too often these play outsize roles that eventually define whole communities, tribes, nations, and even continents of people. To understand the power and danger of the single story, it is important to make the distinction between the past and history. [16] The past is what actually occurred, whereas history is that which is written about the past, in the way historians — who often write as informed by specific social, cultural, economic, ethical, and political perspectives — attended to it. What we know about the past tends to be informed from a certain, often quite biased perspectives. If we were to trust most of what historians have written about how and why particular civilizations and the societies that comprised them evolved over time, many marginalized communities would be rendered virtually nonexistent. The cause of this is their purposeful erasure from so many of the historical canons we use to inform us about the past that have been directly affected by the often myopically restricted lenses through which the individual documenting of the past chooses to look.

History often becomes a means to weaponize various aspects of the past because there is not a truly objective, uninfluenced worldview of it. Thus, it can never completely provide us with accurate retellings of the past without being affected by the influence of capitalism and what have become the toxic normalities of our consumer-constructed culture. A power dynamic will always exist that creates meanings of and about past events as told by those who wield the power in a particular society to influence types and levels of oppression — individual, [a] agentic, [b] institutional, [c] and cultural, [d] — within the broader context. There is no way to avoid the problematic tendencies of history, as it is written. Because those in power dictate the stories of the past that are told, it is these power structures that hold the blame when the narratives of marginalized communities are erased from the past. It is no wonder that when stories of the oppressed are brought to light, those in the dominant group try to suppress those narratives. It is much easier to remember a history crafted to keep one in power than to understand those who were oppressed in the making of that history. As Freire points out:

“There is no history without humankind, and no history for human beings; there is only history of humanity, made by people and (as Marx pointed out) in turn making them. It is when the majorities are denied their right to participate in history as Subjects that they become dominated and alienated. Thus, to supersede their condition as objects by the status of Subjects — the objective of any true revolution — requires that the people act, as well as reflect, upon the reality to be transformed.” [17]

Understanding Your Positionality

One of the first steps required to build understanding of and about your positionality is to critically examine the various social identities that are recognized by the dominant culture in your society, and then use these to construct knowledge about how and why the intersections and intersectionality of those social constructs operate within this socio-cultural norm. Almost all people on our planet live lives that are affected by various aspects of how they perceive themselves — and how they are perceived by others in their society — according to how specific aspects of their identities intersect with each other. These intersections can fuel unique types of discrimination. For example, people who live in the U.S. who can be categorized as Native American and as gay and also as hearing impaired can be forced to confront discriminatory public policies and social behaviors as a result of the sum of the perception of all three of these identities being perceived as “undesirable” or “less than.” When thought about within this contextual framework, intersectionality becomes an apt descriptor for how and why race, class, gender, ethnicity, and other individual characteristics have been categorically used throughout much of the world’s history to ensure that marginalized and underinvested communities remain that way. In short, intersectionality helps ensure that the socio-cultural perceptions of those whose identities reside in the margins of the margins will continue find their paths away from the limitations these impose to be blocked. When Kimberlé Crenshaw first coined this term, she was specifically referring to economically disadvantaged Black women (it has since been expanded to describe much broader cross sections of people):

“Black women are subsumed within the traditional boundaries of race or gender discrimination these boundaries are currently understood, and that the intersection of racism and sexism factors into Black women's lives in ways that can be captured wholly by looking at the race or gender dimensions of those experiences separately.” Intersectionality goes beyond exclusively examining socio-cultural identities that intersect and instead focuses on the identities that tend to be oppressed due to social normalcy within a given society.

“Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects. It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times, that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things.”

— Kimberlé Crenshaw [18]

We have also defined power and privilege for participants; however, we remind participants to leave room for context and nuance when using these terms to define social identities. We define power as earned authority granted through social structures and conventions that affords given individuals and groups access and control over people through the intentional planning and operations of institutions and systems (for example, management, human resources, executive-level leadership). We define privilege as unearned personal, interpersonal, cultural, and institutional rights or benefits that provide or contribute advantages, favors, and benefits to members of dominant groups in a society at the expense of members of target groups within it from whom these rights and benefits are withheld. (In this context, targeted groups are defined by race, gender, sexuality, ableness, ethnicity, etc.). Both power and privilege give dominant groups an upper hand across multiple societal contexts; through these means, they can affect and control public policy, educational initiatives, who gets to live where, and who gets to pursue the most desirable and profitable career paths. Recognizing this upper hand does not negate the challenging work that many individuals engage in to fuel their careers and attain their life achievements. Rather, this recognition is intended to help many types of people — including those who use our Racism Untaught toolkits in workshop settings — to understand that these social constructs make it harder and add more work for individuals in the marginalized categories of the targeted social groups living within a given society.

Breaking Down Social Identities: Introducing Participants in our Workshops to the Workings of the Racism Untaught Toolkit

The Racism Untaught toolkit is designed to be utilized by small groups of participants (four or five) during the operation of a workshop that transpires over the course of two to eight hours. We begin these workshops by asking our participants to engage in an activity that walks them through a process designed to help them acknowledge their social identities. As they do this, we also ask them to begin to build understandings about the roles they each play in forming their own social identities and those of fellow community members, and how these roles are affected by oppressive socio-cultural, political, and economic systems (among others). Engaging in the process of articulating and then navigating their own stories as these transpire, and then acknowledging the historical contexts within which they have evolved, provides participants with the perspectives necessary to analyze the roles they play in upholding various systems of oppression. Jan Stets and Peter Burke, social scientists at Washington State University, study the way people perceive themselves and others, and how these perceptions guide an individual’s social identity. They offer the following insights about this:

“Individuals are born into an already structured society. Once in society, people derive their identity or sense of self largely from the social categories to which they belong. Each person, however, over the course of his or her [their] personal history, is a member of a unique combination of social categories; therefore, the set of social identities making up that person’s self-concept is unique.”

The activities of acknowledging both a particular social structure and the roles one plays within it activates a form of self-identity rooted in what Stets and Burke refer to as, “the psychological significance of a group membership.” [19] These activities are engaged in before participants are introduced to the racialized design challenge, or prompt, that they will use to guide their critical analyses as the workshop progresses. This constitutes the first step that operates within the Racism Untaught framework. It has become an important activity for participants to complete prior to working with the rest of what comprised the Racism Untaught toolkit.

Initiating this activity entails us providing participants with a list of 20 different social identities that are accompanied by descriptions of the roles these play, or occupy, within it. We then ask participants to select five social identities from among the group of 20 they are comfortable sharing. Some of those identities include the “big eight:” race, gender, sexual orientation, class, ethnicity, ability (or ableness), age, and religion. We acknowledge that there are many social identities that we do not list, and that social identities are heavily informed by social ideologies and practices that operate within a particular culture. This has been especially evident in the international workshops we facilitated, and manifests itself in how our participants often provide context to frame the roles (privileged or marginalized) that reside, or “operate,” within each social identity category.

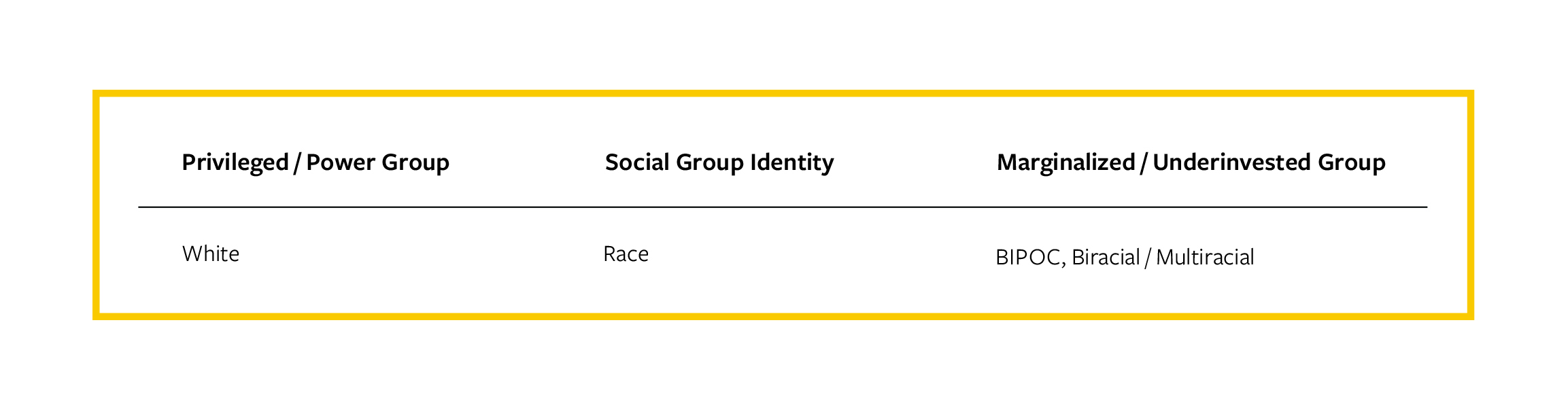

International participants assign different meanings to some of the social groups, which encourages a more nuanced discussion. The social identity groups listed for participants to select from are sub-divided into the roles of privileged or marginalized, which are designated positions or groups in many societies the world over. In the cultural norms that exist in the U.S., these roles take on particular meanings and are governed by a specific identity. For example, one social identity group that is listed is race, and we provide the following articulations for the roles that operate within that social identity group: white people are listed under the privileged / power group heading, and BIPOC and biracial / multiracial are listed under the marginalized groups heading. An example of the table we use to visually communicate these categorizations is offered below.

The only requirement for engaging in this activity involves participants being asked to select the social group identity of race, and then being asked to select whether they are in the privileged / power or marginalized roles that comprise that group. As they engage in these selection processes, participants are afforded opportunities to discuss race in the design challenge that they will soon be prompted to undertake to ensure they have analyzed their own perception of race before participating in broader discussions about racism. Once they have completed these processes, participants are invited to choose four additional identities from the list of twenty that they can then discuss with their group.

The Importance of “Creating Space” within the Structure of our Workshops

In each workshop, we verbally acknowledge that all of the participants are learning new concepts (and how to use them), and language, and we therefore ask them to be open to changes in their and their groupmates thinking, and to be flexible when new knowledge is uncovered or constructed. Marta Elena Esquilin of Bryant University in Smithfield, Rhode Island, and Mike Funk from New York University have written about the importance of community building and the value of crafting and then abiding by engagement agreements. They have provided over 20 classroom and meeting guidelines to create an intentional space within which conversations focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion. [20] We asked Racism Untaught workshop participants to join us in the development of a community agreement that includes the following ideas: 1) to listen actively, 2) to speak from your own lived experience, 3) to repair harm, and 4) to “step in,” and then “step back.”

We also provide definitions that help ensure that all participants are working from a shared understanding of the concepts we are introducing throughout the workshop. We begin with the concept of racism, defining it as the conscious or subconscious belief and / or action that supports the social construct of race as the primary determinant of human capacities and the belief that the most predominant race is inherently superior (prejudice + power over + privilege); that is, the white race is superior to People of Color, at least in the U.S. (and in many other so-called “G-20” nations around the world. We emphasize that Racism Untaught was not created to prove that racism exists in design, but to reveal how deeply racism affects so many aspects of the societal foundation and framework within which design decision-making occurs. In short, we work to sensitize workshop participants about approaches and methods for creating and operating design approaches that are guided by perspectives framed with an anti-racist lens.

Additionally, participants in workshops that focus on analyzing sexist or intersectional artifacts, systems, or experiences are provided with a particular definition of sexism. It is offered as the conscious or subconscious belief and / or action that supports the sex assigned at birth as the primary determinant of human capacities, which guides the belief that the male sex is inherently superior (prejudice + power over). More simply put, the definition of sexism that we offer our participants in these types of workshops is that the male sex is superior to female or intersex individuals.

Exploring How Discussions About Humility, Vulnerability, and Transparency Positively Affect Workshop Participants’ Experiences

We acknowledge that humility and vulnerability are keys to having productive conversations among participants in the workshops within which the Racism Untaught toolkit is utilized. It is important that both the facilitators and participants do not themselves claim to be or assume others to be experts on the topic of racism, especially if that assumption is based on cultural identity. There exists a toxic expert culture, especially across academia, that has often hindered our ability to work in a transdisciplinary manner [21] that could help us — and our workshop participants — learn new ways of thinking (that is, engage in so-called higher learning activities). The work of unpacking racism is heavy and often hard to do, but it is necessary if we hope to move our organizations and classrooms forward regarding how it is addressed — or not — when coupled with planning and operating design processes necessary to do this effectively. New language is being developed in and around these topics every day, and this is directly and indirectly affecting how these evolve. Because of this, we ask participants to be willing to acknowledge the fact when they do not know or cannot effectively articulate an answer to a question or a prompt, and suggest that it is imperative that they do their own research so that further misconceptions or miseducation does not occur.

It is beneficial for facilitators and participants in the workshop within which the toolkit is used to be transparent about recounting their own history(ies), to be and offer these up willingly. Doing this helps create a space within which others can be freely allowed to share their own history(ies). We have found that one effective way to talk about your past is by using the Where I Am From poem by George Ella Lyon [22] to help workshop participants articulate how their identities are shaped by things, events and incidents that transpired in their pasts. We have participants create this poem, critically assessing where cultural bias is present in their social upbringing. We also recommend having participants do a visual element or collage with their poems to present to their design team. This will allow for a long and deep look into their past and the critical assessment of racialized design in their background. Transparency grants people who have never talked about these subjects the grace to learn and grow from their mistakes. Absolutely no one is perfect, and, in fact, the Racism Untaught toolkit reveals to participants that everyone plays a role in the perpetuation of racism.

Accounting for and Minimizing Triggers and Discomfort Among Racism Untaught Workshop Participants

Because racialized design is so deeply embedded in U.S. culture, it is important to recognize that racialized trauma will exist with BIPOC individuals and groups who choose to participate in the workshops within which Racism Untaught is used. One way in which we have learned to plan for the cultural taxation that participating in our workshops may cause is by offering affinity spaces within which BIPOC can work with each other, which we have found helps to shield them from feeling the pressure of having to teach white colleagues about their racialized experiences. It is imperative to be sensitive to these traumas and to have a plan of action if participants feel triggered into feeling uncomfortable.

Remember that there is also a difference between being triggered and being uncomfortable. Being triggered entails intense emotions linked to a traumatic experience that cause a response such as fight, flight, freeze, or fawn. [23] Trauma can show up when you least expect it, so using the aforementioned community agreement is a terrific way to help validate and repair harm. Being triggered is often confused with the feeling of discomfort that individuals within the dominant groups tend to feel when confronted with issues dealing with systems of oppression they benefit from. In order to grow, participants should lean into this discomfort with topics they do not usually discuss, especially when they hold the power and privilege in that context. Crystal Raypole gives an example of coming to understand this matter better in the following excerpt from the book What It Means to Be Triggered:

“I already knew how racist the restaurant business was and how sexist it was too. But to face that would mean I would have to face how I was implicated in this system. And so, I ran away that day so that I could avoid feeling that discomfort and continue to reap the benefits of my whiteness.” [24]

Utilizing Well-Crafted Language to Foster Effective Critical Analysis About How and Why Organizational Structures Can Foment Racism and Sexism

Diversity, equity, and inclusion are institutional buzzwords associated with planning and doing social-justice-centered work. They are palatable words that many organizations use to avoid the uncomfortable conversations that would happen if they admitted their organization operationally affected by overt or more insidious manifestations of racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, etc. These palatable buzzwords often skirt the genuine issues that affect organizational operations (and perceptions of these) and conflate racism and sexual harassment with “bullying.” This kind of downplaying is a barrier to both progress and the uncovering of oppressive systems that further perpetuate the marginalizing nature of the systems that have been designed and operationalized to affect how we live, work and play.

We emphasize intention throughout our workshops within which the Racism Untaught toolkit is utilized. Words have and communicate quite deliberate meanings within given societal contexts, and being specific about the words participants choose to use is essential to the design process. Achieving this kind of clarity helps individuals to contextualize (see figure 4) and not make assumptions. During this process of contextualizing your positionality with your design team, it is helpful to understand before being understood so that the responses we give can be well informed. For instance, when participants talk about their racial identity versus their ethnicity, it is an important opportunity to uncover areas of privilege and power associated with their experiences. Understanding the complexities of participants whose racial identity differs from their ethnicity can be hard for some, so taking time in this process of unlearning racial biases is important.

Purposeful language used throughout onboarding sets participants up to be intentional throughout the design process. It also helps people understand how meaning can shift depending on context — time and culture. Being sensitive to how we express ourselves and how we accept the expression of others helps everyone in the research process feel comfortable making mistakes and learning from one another.

Exploring Ways to Make Intentionally Anti-Racist Choices as Design Processes Evolve

In addition to having hard conversations, we routinely ask workshop participants to initially consider the question, “How does the knowledge or unawareness of our own identities affect the way we design?” We then ask them to consider two more questions: “What identities are at the forefront of your mind or the ones you lead with most?,” followed by, “How do your identities shape how you move about the world?” We also ask workshop participants to consider how and why these questions affect how they perceive and how they might need to re-perceive, the artifacts, systems, and experiences they utilize and (perhaps) support on a day-to-day basis. One example is artist and designer Eric Gill, one of the most respected artists and designers of the twentieth century, who was also a convicted pedophile. [25] His work is included in the permanent displays of multiple museums, including the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft; [26] his sculpture Creation of Adam is on display in the Palais des Nations, the European Headquarters of the United Nations in Geneva; and designers continue to use the typefaces he designed, Perpetua and Gill Sans. The BBC asked the question, “Can the art of the paedophile be celebrated?” [27] Would this same difficulty not apply to forms of racialized design? It is critical that we identify invisible forms of oppression that exist in design and ensure the acknowledgement of cultural habits that are considered invisible and that ultimately perpetuate various forms of oppression. [28]

These considerations are true for both the pedagogical approach to design and the exclusivity inherent in the practice of traditional design. The design research process is not inherently inclusive. [29] Therefore, design interventions that question the colonial slant of design pedagogy are imperative to the progress of the contemporary practice of design. Freire writes:

“How can a designer be designed to provide care via the designing of things that ontologically care? ... . It requires an understanding of design’s implication in the state of the world and the worlds within it. To gain this understanding means fully grasping the scale and impact of design as an ontological force of and in the world in its making and unmaking.” [30]

It is vital to acknowledge the experience all people bring to their own practice of design and provide them with the space to explore how their individual social identity will be present in their process of making. This will require an iterative way of working at the foundation of their practice to ensure an individual’s skills and their own practice of design is evolving and overlapping with the understanding of their positionality.

The continual, iterative nature inherent in the process of developing design interventions is important because meaning and language shift across time and space. As Freire also writes, “As times change so do attitudes and beliefs.” [31] His book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, describes the importance of people’s continuing to work toward an understanding of inclusive language. The Racism Untaught framework provides participants with an ever-growing and evolving set of terms with which they can critically analyze forms of racialized design.

To further anti-racist design decision-making, we address the toxic binary of power and privilege by creating space to discuss and acknowledge harm. This can be done through restorative design and a practice of transformative justice. [32] Students respond in a positive way to critically analyzing forms of racialized design and are motivated to work toward re-imagining design approaches.

Conclusion

During each workshop, participants often expressed their desire for more time during each segment of the operation of the toolkit, but particularly during the onboarding process. We have answered this request by discussing the plethora of opportunities that exist to continue their own, personal work toward understanding their positionality. It is our hope that participants in Racism Untaught workshops continue the life-long journey of understanding their positionality so that they can make well-informed and anti-oppressive design decisions. Using the onboarding process as a door to conversations on race and racism has helped participants become vulnerable yet also more knowing about their own implicit and explicit biases which allows them to engage in open dialogue about how their design decisions impact BIPOC.

We would encourage readers of this article to engage in introspective practices so that they might come to better understand how and why their power, privilege, and specific marginalizations exist as they do. Facilitating the number of workshops that we have has taught us that gaining and cultivating understandings of and about these is integral to leveraging the power of design processes, and the outcomes they yield, to counter numerous types and levels of oppression. Engaging in self-assessments, as suggested by the parameters that guide the operation of the Racism Untaught toolkit, can be an effective way to understand how an individual “shows up” and is perceived (by others and by themselves) in particular social spaces. These kinds of activities can also begin to help individuals and small groups analyze how the socialization of cultural norms attributes to how they show up and are perceived, internally and externally. These kinds of activities are also important for educators to plan and operate because the often-unchecked power of instructors wielded in their classrooms, when paired with racial, sexist, ableist, and classist tendencies, can make for a toxic educational environment within which students are not inclined to learn. We would also encourage Dialectic’s readers to explore the authors whose work has been analyzed in this piece to help them better understand how the traumas of systemic racism can manifest themselves in our bodies. Books such as My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies by Resmaa Menakem [33] may also prove useful as guides for information and coping strategies regarding these issues. The work of anti-racism is not easily initiated, much less sustained, and there will be times during which your well-intentioned efforts may unintentionally do more harm than good, but — be encouraged: you may not be an expert on racism — or anti-racism — but, as a designer or a design educator, you have a responsibility to at least try to use your power to affect thegood of humanity, whether your efforts occur on a local, regional, national or international scale.

Biographies

Terresa Moses (she / her) is a proud Black, Queer woman dedicated to utilizing approaches and methods rooted in art and design to ensure the liberation of Black and Brown people. As a designer and illustrator, her work focuses on race, identity, and social justice. She is the creative director at the design consultancy Blackbird Revolt, and an Assistant Professor of graphic design and the Director of Design Justice at the University of Minnesota. As a community engaged scholar, she created Project Naptural, a design research study that examined ways design processes can assist Black women overcome negative perceptions about their naturally afro-textured hair. She also co-created the Racism Untaught toolkit with University of Illinois Assistant Professor of graphic design Lisa Mercer. She serves as a core team member of African American Graphic Designers and as a collaborator with the Black Liberation Lab. [email protected]

Lisa Mercer (she / her) is an Assistant Professor of Graphic Design and Design for Responsible Innovation at the University of Illinois. Her research interests are centered in developing and executing design interventions that responsibly fuel and sustain responsible design for positive social impact. Her work has been integrated into academic, industry, and community settings. The developed frameworks and tools she has created and co-created are meant to frame, support and sustain a space for conversation and knowledge exchange wherein participants can actively collaborate in the instantiation and creation of new ideas and solutions. This type of methodology is evident in the development and realization of all of her major projects. [email protected]

References

- Adichie, C.N., “The Danger of a Single Story,” TED Global, 29 July 2009. Available at: https://bit.ly/3tKWC1B. (Accessed April 8, 2021).

- Amico, R. P. Exploring White Privilege. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2017.

- Appleby, J. O., Hunt, L., & Jacob, M. C., Telling the Truth About History. New York, NY, USA: Norton, 1995, pgs. 22–44.

- Bonds, A., Inwood, J., “Beyond White Privilege: Geographies of White Supremacy and Settler Colonialism.” Progress in Human Geography, 6.40, (2016): pgs. 715–33.

- Byrne, C. “The BMI Is Racist and Useless. Here’s How to Measure Health Instead.” The Huffington Post. 20 July, 2020. Online. Available at: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/bmi-scale-racist-health_l_5f15a8a8c5b6d14c336a43b0. (Accessed June 22, 2021).

- Carroll, A. “Can Design Dismantle Racism?” YouTube video, 12:47. TEDxHerndon, May 10, 2017. https://www.ted.com/talks/antionette_carroll_designing_for_justice. (Accessed August 5, 2021).

- Crenshaw, K. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review, 43.6 (1991): pgs. 241-299.

- Davis, L.J., ed. The Disability Studies Reader: Constructing Normalcy. London, UK: Routledge, pgs. 3–16. 2006.

- Escobar, A. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, London, UK: Duke University Press, 2017.

- Esquilin, M. E. & Funk, M. “Campus Bias Incidents: What Could Faculty Do? Navigating Discussions in the Classroom.” Resource pre-sented at Bryant University, Smithfield, Rhode Island, USA, November 2019. Online. Available at: https://cte.bryant.edu/wp- content/uploads/2018/10/Bryant-handouts-Nov-2019-PDF.pdf (Accessed 8 April 2021).

- Freire, P., Ramos, M. B., Shor, I., & Macedo, D. P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 50th Anniversary Edition. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

- Fuller, S. & Butcher, A. “Eric Gill: Our Response.” Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, February 2021. Online. Available at: https://www.ditchlingmuseumartcraft.org.uk/ (Accessed August 5, 2021).

- Hicken, M.T. et al. “The Weight of Racism: Vigilance and Racial Inequalities in Weight-Related Measures,” Social Science & Medicine, Feb. 199 (2018): pgs. 157–166.

- hooks, b. Teaching to Transgress: Education As the Practice of Freedom. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 1994.

- Hum, S. “Between the Eyes": The Racialized Gaze as Design.” College English, 77.3 (2015): pgs. 191-215. Online. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24238161 (Accessed April 11, 2021).

- Jenkins, K. Rethinking History. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2003; pgs. 7-32.

- Kang, M., Lessard, D., Heston, L., & Nordmarken, S. “Introduction: Binary Systems.” In Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies. Online. Available at: https://openbooks.library.umass.edu/introwgss/chapter/introduction-binary-systems/#:~:text= Binaries%20are%20social%20constructs%20composed,to%20have%20nothing%20in%20common. (Accessed August 8, 2021).

- Lyon, G.E., Landsman, J., “I Am From Project,” Online. Available at: https://iamfromproject.com/ (Accessed August 5, 2021).

- Menakem, R. My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas, NV, USA: Central Recovery Press, 2017.

- Morris, R., Stories of Transformative Justice. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Scholars Press, 2000.

- Raypole, C., “What It Really Means to Be Triggered,” edited by Legg, T., Healthline, 25 April 2019, Online. Available at: https://www.healthline.com/health/triggered (Accessed 8 April 2021).

- Rohrer, F. “Can the Art of a Paedophile be Celebrated?” BBC News Magazine, 5 September 2007. Online. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/6979731.stm (Accessed 8 April 2021).

- Stets, J., Burke, P., “Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory.” Social Psychology Quarterly, 3.63 (2000): pgs. 224–37.

- Tarman, C., Sears, D., “The Conceptualization and Measurement of Symbolic Racism,” The Journal of Politics, 3:67 (2005): pgs. 731–761.

- Wowk, K., McKinney, L., Muller-Karger,F., et al., “Evolving Academic Culture to Meet Societal needs.” Palgrave Communications: Humanities and Social Sciences Communications Journal, 21 November, 2017. Online. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-017-0040-1 (Accessed August 5, 2021).

Notes

- a

Individual oppression is fueled by personal beliefs, ideas, and feelings that perpetuate oppression.

- b

Agentic action occurs when oppressive beliefs translate into oppressive behavior.

- c

Institutional oppression occurs when structural oppression results from agentic, oppressive behavior.

- d

Cultural oppression is fueled by well-entrenched systems of norms, values, beliefs, and trusted systems of acquiring truth that preserve, protect, or maintain oppression.

hooks, b. Teaching to Transgress: Education As the Practice of Freedom. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 1994.

Tarman, C., Sears, D., “The Conceptualization and Measurement of Symbolic Racism,” The Journal of Politics, 3:67 (2005): pgs. 731–761.

Hicken, M.T. et al. “The Weight of Racism: Vigilance and Racial Inequalities in Weight-Related Measures,” Social Science & Medicine, Feb. 199 (2018): pgs. 157–166

Amico, R. P. Exploring White Privilege. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2017.

Freire, P., Ramos, M. B., Shor, I., & Macedo, D. P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 50th Anniversary Edition. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Kang, M., Lessard, D., Heston, L., & Nordmarken, S. “Introduction: Binary Systems.” In Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies. Online. Available at: https://openbooks.library.umass.edu/introwgss/chapter/introduction-binary-systems/#:~:text=Binaries%20are%20social%20constructs%20composed,to%20have%20nothing%20in%20common.(Accessed August 8, 2021).

Davis, L.J., ed. The Disability Studies Reader: Constructing Normalcy. London, UK: Routledge, pgs. 3–16. 2006.

Appleby, J. O., Hunt, L., & Jacob, M. C., Telling the Truth About History. New York, NY, USA: Norton, 1995, pgs. 22–44.

Hicken, M.T. et al. “The Weight of Racism: Vigilance and Racial Inequalities in Weight-Related Measures,” Social Science & Medicine, Feb. 199 (2018): pgs. 157–166.

Byrne, C. “The BMI Is Racist and Useless. Here’s How to Measure Health Instead.” The Huffington Post. 20 July 2020. Online. Available at: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/bmi-scale-racist-health_l_5f15a8a8c5b6d14c336a43b0. (Accessed June 22, 2021).

Davis, L.J., ed. The Disability Studies Reader: Constructing Normalcy. London, UK: Routledge, pgs. 3–16. 2006.

Bonds, A., Inwood, J., “Beyond White Privilege: Geographies of White Supremacy and Settler Colonialism.” Progress in Human Geography, 6.40, (2016): pgs. 715–33.

hooks, b. Teaching to Transgress: Education As the Practice of Freedom. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 1994.

Adichie, C.N., “The Danger of a Single Story,” TED Global, 29 July 2009. Available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare. (Accessed April 8, 2021).

Jenkins, K. Rethinking History. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2003; pgs. 7-32.

Freire, P., Ramos, M. B., Shor, I., & Macedo, D. P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 50th Anniversary Edition. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Crenshaw, K. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review, 43.6 (1991): pgs. 241-299.

J. Stets and P. Burke, “Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory.” Social Psychology Quarterly 63.3 (2000): 224–37.

Esquilin, M. E. & Funk, M. “Campus Bias Incidents: What Could Faculty Do? Navigating Discussions in the Classroom.” Resource presented at Bryant University, Smithfield, Rhode Island, USA, November 2019. Online. Available at: https://cte.bryant.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Bryant-handouts-Nov-2019-PDF.pdf (Accessed 8 April 2021).

K. Wowk, L. McKinney, F. Muller-Karger, et al., “Evolving Academic Culture to Meet Societal needs.” Palgrave Commun 3, Humanities and Social Sciences Communications Journal, 35 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0040-1.

Lyon, G.E., Landsman, J., “I Am From Project,” Online. Available at: https://iamfromproject.com/ (Accessed August 5, 2021).

Raypole, C., “What It Really Means to Be Triggered,” edited by Legg, T., Healthline, 25 April 2019, Online. Available at: https://www.healthline.com/health/triggered (Accessed 8 April 2021).

Amico, R. P. Exploring White Privilege. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2017.

Rohrer, F. “Can the Art of a Paedophile be Celebrated?” BBC News Magazine, 5 September 2007. Online. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/6979731.stm (Accessed 8 April 2021)

Fuller, S. & Butcher, A. “Eric Gill: Our Response.” Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, February 2021. Online. Available at: https://www.ditchlingmuseumartcraft.org.uk/ (Accessed August 5, 2021).

Rohrer, F. “Can the Art of a Paedophile be Celebrated?” BBC News Magazine, 5 September 2007. Online. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/6979731.stm (Accessed 8 April 2021).

Hum, S. “Between the Eyes": The Racialized Gaze as Design.” College English, 77.3 (2015): pgs. 191-215. Online. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24238161 (Accessed April 11, 2021).

Carroll, A. “Can Design Dismantle Racism?” YouTube video, 12:47. TEDxHerndon, May 10, 2017. https://www.ted.com/talks/antionette_carroll_designing_for_justice. (Accessed August 5, 2021).

Escobar, A. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, London, UK: Duke University Press, 2017.

Freire, P., Ramos, M. B., Shor, I., & Macedo, D. P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 50th Anniversary Edition. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Morris, R., Stories of Transformative Justice. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Scholars Press, 2000.

Menakem, R. My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Las Vegas, NV, USA: Central Recovery Press, 2017.