Design Exploration as a Research Discovery Phase: Integrating the Graduate Design Thesis with Research in the Social Sciences

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Contemporary research problems are complex, and design must better integrate with the social sciences to have an equal part in addressing them. The terminal master’s degree in design (usually an MFA or MDes in the United States) can prepare students for this integration, but doing so requires that design activity be adapted to ultimately contribute to evidence-based research, rather than remaining unchanged and retroactively deemed to be a form of research. To achieve this end, I present design-based discovery, a model of design inquiry that situates design within the theory development cycle as theory building, not theory testing. Design-based discovery has recently been codified in a master’s program in graphic design at a public research university in the US. In this article, I outline six investigation components that together represent this model, and support these with examples. Notably, the investigation components include a standardized format for research questions, as well as the derivation of design principles from processes that involve exploration rather than those that yield solutions. This model can readily be adopted in other master’s programs with the requisite resources, which has the potential to make design essential within research universities.

Introduction

Contemporary design research problems are increasingly complex, and design educator Meredith Davis recently outlined considerable limitations of master’s degrees in design for addressing such problems.[1] Design research must continually evolve in both academia and industry, and with the extensive professional skills that overload undergraduate design education, the terminal master’s degree (usually an M.F.A. or M.Des. in the United States) must play a central role and “enrich the capabilities offered by the profession.”[2] Davis lists the following experiences that graduates of master’s programs in design are too rarely afforded:

- Posing “truly researchable questions,”

- Recognizing “multiple research paradigms and their corresponding standards,”

- Structuring “methodically rigorous investigations,” and

- Authoring “papers longer than a few pages.”[3]

In the absence of these experiences and the competencies they develop, such graduates are perhaps prepared to address the “well-structured problems of appearance and function” of the past, but not the interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary work required today.[4] When nominal research engagement in industry can often be characterized as opinion, “practitioners’ personal experiences,” or idiosyncratic case studies,[5] graduate education represents an opportunity to indirectly improve design research,[6] making it more generalizable and thus more impactful. Graduates of master’s programs can bring research competencies into industry, or else remain in academia as professors to develop these competencies in their students, who continue the cycle. Those who remain in academia will also directly contribute their own research production.

To enable these benefits for the emerging discipline of design, I will focus on a foundational characteristic of contemporary research problems emphasized by Davis: for many such complex problems, no single discipline alone can address them.[7] My objective is thus to empower designers to collaborate with researchers in other disciplines — especially within the social sciences — by articulating a model of design inquiry that can be implemented in master’s programs in design. This model of design inquiry, or design-based discovery, is complementary to and compatible with much of research practice in the social sciences.[a]

To facilitate adoption of this model in other master’s programs, I will describe the following: the context of the current implementation; the investigation components students must produce; criteria for evaluation of the components; select examples of the components that make descriptions more tangible; and the student competencies that must be developed, including requisite coursework and institutional infrastructure. The relationship between design programs and research as it is known elsewhere in universities has important implications. For instance, the long-term health and viability of design, in contexts that value and evaluate research outcomes, is dependent upon design’s representatives — in academia, these representatives are design faculty.

Davis has suggested that design faculty are in danger if they merely position themselves as special within universities, as opposed to demonstrating how they are essential.[8] Within research universities particularly, design faculty must either isolate themselves or find ways to meaningfully interact with experts in other disciplines. Many funding agencies, such the National Science Foundation in the United States, expect evidence-based inquiry of the highest standards, and will not make exceptions for design’s specialness. While design faculty often define design research in a manner exempt from the scholarly standards at universities, Davis warns that:

“...alternate rules of play for design faculty undermine the development of a mature research culture and keep the discipline on the perimeter of many activities that universities value most. Further, they limit the ability of design faculty and graduate students to work as equal partners in funded research that has impact beyond the university.”[9]

Design-based discovery positions design exploration as a research discovery phase in the social sciences, making design essential. It does so without claiming that normal design activity results in the generation of new knowledge, that being a standard of evidence-based inquiry. As such, it makes no attempt to replace research in the social sciences, but aims to contribute to it.

The Master’s Degree in Design

Traditional design education emphasizes doing design over studying it, without teaching students how to base design decisions on empirical evidence or to interpret research conducted in non-design disciplines.[10] There is confusion about the place of research in design curricula[11] and what constitutes academic design research.[12] New doctoral programs (both Ph.D. and D.Des.) and master’s programs are proliferating against the backdrop of this confusion, expanding postgraduate offerings at a time when designers still have difficulty resolving design research with “typical” academic research.[13] During this period of expansion, design programs and the discipline as a whole must negotiate the very definition of research in design[14]

Undergraduate study in design is vocational, and graduate study, at least in the United States and especially under the most common M.F.A. designation, often continues vocational education with little differentiation from undergraduate study. Master’s programs frequently follow a fine arts curricular model, sometimes with minimal coursework in favor of independent study that is only occasionally subject to faculty critique, which tends toward an emphasis on the development of artifacts to the exclusion of effectively engaging in research methods[15]

Master’s study must be constrained in part according to what program faculty consider to be the nature of research — whether they believe their program enables mastery of that kind of research, or is preparatory for it. Doctoral study represents the highest level of research practice, and thus when a doctoral program is adjacent to a master’s program, or when faculty have a concrete notion of what doctoral study represents, it can serve as a lodestar by which master’s study is oriented and understood. Both practice-based and evidence-based doctorates exist. The practice-based doctorate has making as central to its model and is familiar territory for designers, where faculty need not adapt their design practices to other standards of research.[16] The evidence-based doctorate is less familiar to designers and may entirely exclude any studio-based activity. The evidence-based dissertation investigates some phenomenon as experienced by others. It does not center on a singular artifact or system of artifacts of the student’s making, nor does it ask the researcher to engage in self-observation. Evidence-based doctoral programs train students to engage in rigorous methodologies, employ specific sampling methods, and analyze statistics to compare and assess data, all of which are beyond the scope of what can be covered in two-year’s worth of study at the master’s level. Nevertheless, master’s students can develop “research-sensitive dispositions,” and apply knowledge from other disciplines in their work.[17] A master’s degree can stage more open-ended design exploration in studio-based courses while developing academic research behaviors in other courses that involve little or no design activity. It can thus serve as a bridge between familiar design practices and foreign research practices.

Design and Research Practices

Scholarship on research in design — or research as conducted by designers — has predominantly been concerned with learning more about design activity itself; that is, how designers go about designing.[18] An increasing understanding of the nature of design activity[19] has led, among other paths, to practice-based or practice-led design research,[20] which is the basis of practice-based doctorates. Practice-based design research commonly utilizes own design, in which design researchers effectively intend to learn more about the nature of design by themselves designing.[21] This blurs the distinction between “works of practice” and “works of research” in design that Cross argues should be maintained,[22] and relies on the researcher’s own opinion and individual experience,[23] which is subject to profound bias. Generally, research is inconsistently defined in design, and design research can thus be “vulnerable to claims of superficiality.”[24] Definitions of design research, especially oft-cited definitions by Frayling[25] and Archer,[26] are ambiguous enough to be inconsistently interpreted and enacted to suit preconceptions and needs.[27] Frayling’s articulation of design research[28] was a means to place art and design within broader academic research practices, but he outlined types of design research by retroactively labeling what designers already “actually do” in practice as research, rather than detailing what might be done differently to integrate design with relevant and well-established research practices.[b]

In contrast to practice-based design research, inquiry in the social sciences is primarily aimed at producing new and generalizable knowledge. In this context the anecdote, upon which the own design of design-based research is predicated, is deeply problematic. Research practices in much of the social sciences seek generalizable knowledge, the methodological reduction of bias, and to minimize the degree to which outcomes are anecdotal.

Philip Cash provides a model of theory development[29] — that which is required in the production of generalizable knowledge — which can effectively delimit design activity. Cash’s theory development cycle includes three phases of theory building and two phases of theory testing (Figure 1). Theory building begins with discovery and description, which involves “identifying areas of interest and important issues” by “asking questions that establish the general characteristics of what is going on in a situation.”[30] It continues with definition of variables and limitation of domain, which involves “identifying variables and mapping interconnections and boundaries” by “asking questions to identify the key variables and identify salient themes, patterns and categories.”[31] The variable of interest is so often central to inquiry in the social sciences, especially in relation to generalizability. Measurement according to variables of interest is a matter of the theory testing mode, which in a cycle subsequently feeds back into the theory building mode, incrementally increasing knowledge. This is the new knowledge of evidence-based inquiry — the “it is known” of a knowledge community[32] — not personal knowledge (the “I know”).

It is unnecessary for designers to come into established disciplines and invent new modes of testing and validation. Instead, with Cash’s theory development cycle, design activity is by its nature a matter of “discovery and description” — particularly as a form of lateral thinking (i.e., a nonlinear and creative way to indirectly address problems). Furthermore, if designers have at least a familiarity with the knowledge bases rooted in the social sciences, they can think in terms of the “definition of variables and limitation of domain” that is required in moving the outcomes of discovery further through theory development.

Design-Based Discovery: An Academic Model of Design Inquiry

I here describe design-based discovery, a model of design inquiry that rigorously guides design exploration as a research discovery phase in the social sciences. Discovery refers to finding something at least somewhat unexpected, which regularly occurs in design exploration. Design-based discovery is distinct from the practice-based model of research through design[33] in two fundamental ways: (1) it does not consider normal best practices of design to include or preclude theory testing, instead delimiting design activity in relation to, and within, the full theory development cycle; and (2) it is not concerned with finding a solution, but instead is meant to produce variability that can then lead to subsequent phases of the theory development cycle. Variability is inherent in any design exploration.

There is a humility to this — design activity is not asked to be the full theory development cycle’s equal. Instead, design exploration represents a discovery phase.[34] Research through design is concerned with producing “the right thing,”[35] which, being solution-based, remains concerned with the anecdotal. In contrast, a model that seeks a range of possible things is more appropriate for incorporating design as an essential part of continuing evidence-based inquiry. [c]

Design-based discovery has been implemented in a master’s program that includes extensive studio-based instruction, where there is not enough time for students to gain expertise in established empirical methodologies in the social sciences. But designers can collaborate with experts in other disciplines if they have a basic understanding of the language of the social sciences and the means to leverage their design capabilities within a theory development cycle. Unlike expertise, this degree of familiarity can be achieved in the context of a master’s program in design.

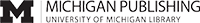

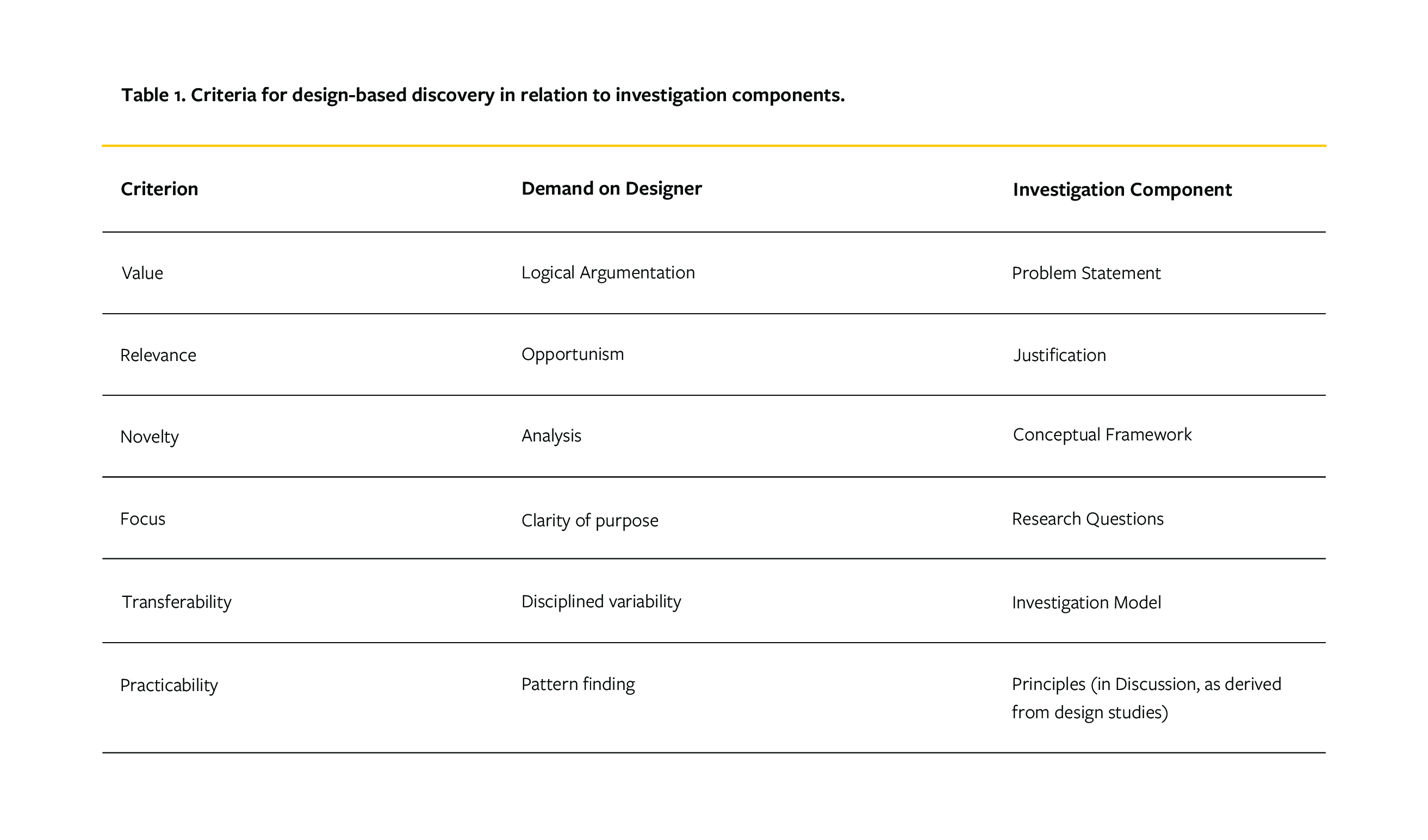

I propose six primary criteria for design-based discovery: value, relevance, novelty, focus, transferability, and practicability. When these criteria are met, the investigation is operable in the social sciences, or able to be utilized and to function as a discovery phase in evidence-based inquiry. Each criterion is directly associated with one component of the investigation: problem statement, justification, conceptual framework, research questions, investigation model, and design principles. Each of these components demands something particular of the designer, which must be supported in earlier coursework. The investigation components determine and, in the case of the principles, respond to visual and interactive studies (i.e., design exploration). The criteria and components are summarized in Table 1, while component relations are depicted in Figure 2.

In their description of a practice-based Ph.D., Pedgley and Wormald appeal to the designer’s considerable skill as a justification for treating that work as research.[36] In contrast, design-based discovery as a model itself ensures that the work is relevant to and implicitly integrated within inquiry in the social sciences. Like any other endeavor undertaken by full cohorts of students, the quality of responses will fluctuate, while the model endures.

Development of the Model

The context of design-based discovery outlined here is a two-year terminal professional master’s degree at a research university in the United States: the Master of Graphic Design, which roughly covers communication and interaction design, within the College of Design at North Carolina State University. The college also includes a corresponding four-year professional bachelor’s degree in graphic design (as well as bachelor’s and master’s degrees in other design disciplines), and a non-disciplinary, evidence-based Ph.D. in Design. Like the bachelor’s degree, the master’s degree features studio-based instruction, but it also includes a curated program of critical readings with substantive, ongoing writing demands. The doctoral program continues the latter, but adds cognate coursework — methods courses taken in other disciplines at the university — and statistics or philosophy. Both graduate levels of study include literature review, but at the master’s level students are utilizing theory, while at the doctoral level and with increased expertise students go beyond simply utilizing theory to interrogating and developing it (or “theory testing,” in Cash’s terminology[37]). Master’s level work in core studios is more speculative and critical. Doctoral work produces new knowledge in the strictest sense — not self-knowledge or anecdotal reports of exploration, but generalizable knowledge.[38]

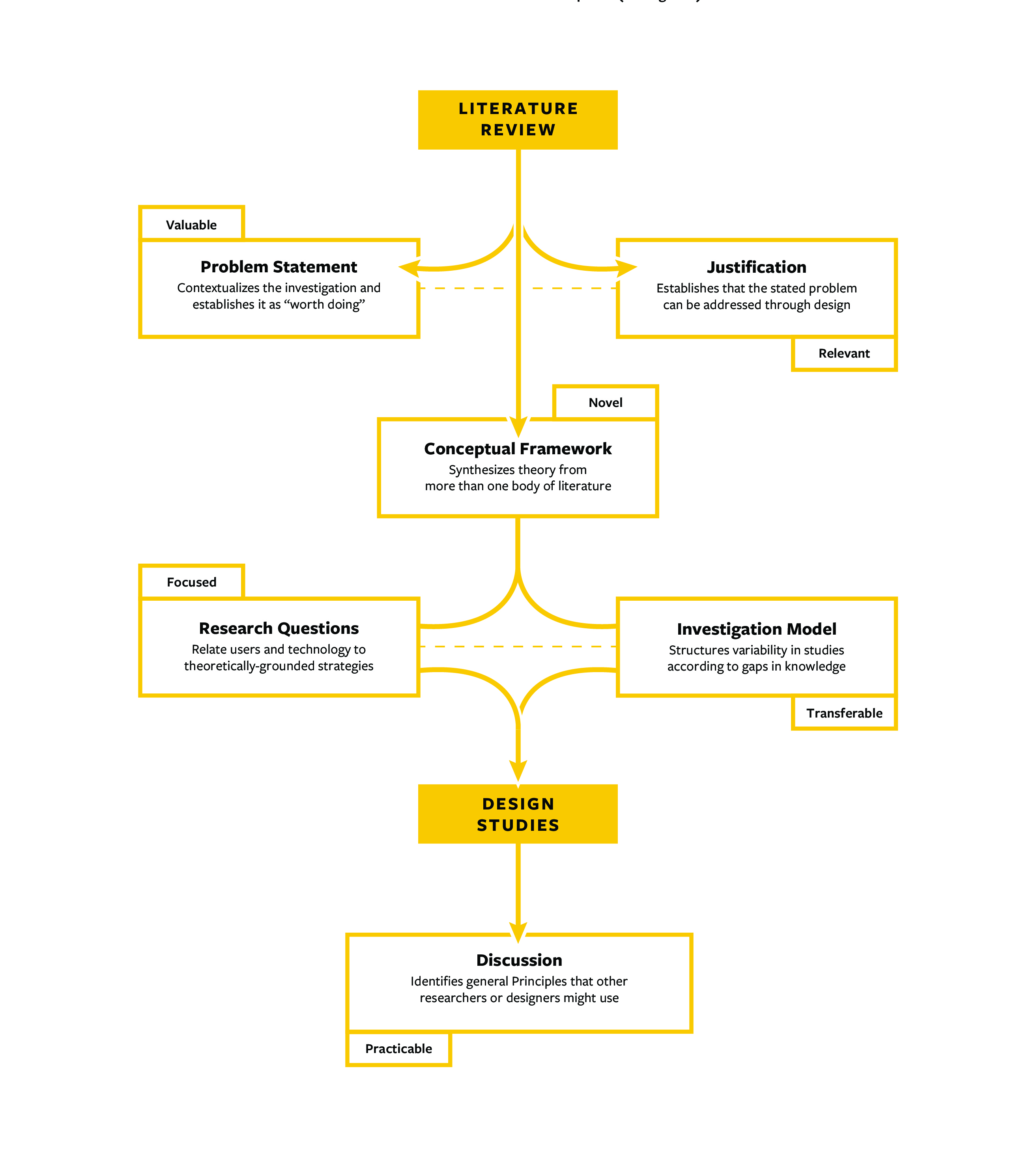

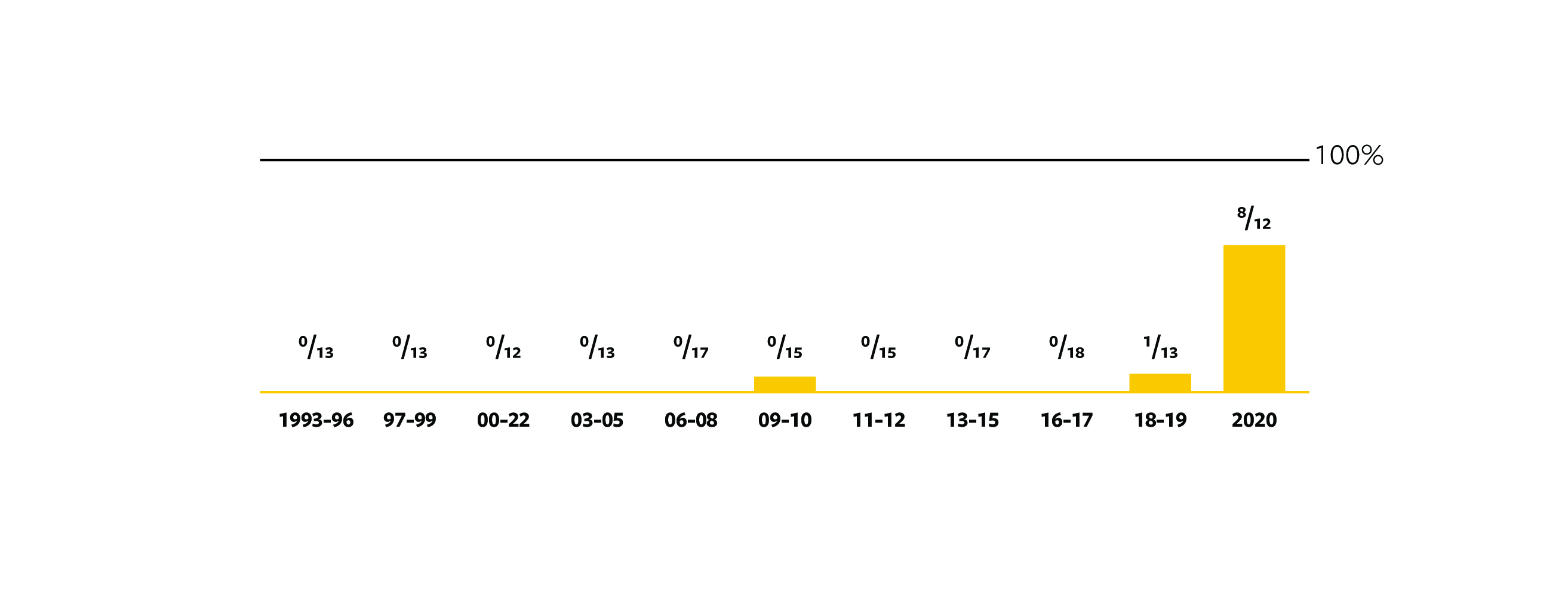

In the Master of Graphic Design program, students produce a thesis document (the university designates this kind of thesis a “final project”), which is physically archived and accessible in a university branch library. I searched available thesis documents for the presence of the six investigation components of the current model (listed in Table 1), to ascertain the degree to which the model is emergent rather than invented. The earliest archived thesis document is from 1993, and 158 total documents were available for analysis. After clustering into groups sized 12–18, beginning with 2020 and working backward, I was able to track trends over 11 consecutive periods of time. Though many individual investigation components occur somewhat frequently across the history of the thesis document (Figure 3), very few documents fully conform to the current standards with all six components present (Figure 4). This demonstrates that all components were at least occasionally present in previous years, when thesis document structure varied significantly and was largely determined on an individual basis by the thesis student and a faculty committee chair (who oversaw the development of the thesis document). It also appears to confirm a general history of the Master of Graphic Design thesis as personally relayed by Meredith Davis, who was instrumental in the evolution of the thesis in N.C. State’s Master of Graphic Design program over much of its history, and who established a thesis preparation course over twenty years ago. The thesis preparation course created a space for standardization. Unsurprisingly, the theses from the 1990s that predated this course, which was launched in 1998, are especially inconsistent in how they envision research.

Though all of the investigation components of design-based discovery appeared during Davis’ tenure, the standardization of design-based discovery as a model occurred more recently, after her direct involvement in the master’s program ended. The codification of design-based discovery involved analyzing recent thesis approaches that appeared to best align with other disciplinary research at the university, and coordinating these approaches. Of the investigation components that came to form the model, the least frequent, and thus the most emergent, is the articulation of design principles that follows the studies. Deriving principles from the studies is meant to transcend the investigation as an anecdote — so this component is a defining characteristic of design-based discovery. Each of the design-based discovery criteria are discussed below, along with their corresponding investigation components.

Value

The criterion of value necessitates that the investigation is worth doing, and yields impacts well beyond the student’s personal growth, or what might merely begin an interesting conversation. This is accomplished through the problem statement, an early section of the thesis document. Establishing value requires logical argumentation.

To demonstrate that a problem space is worth exploring, the designer must provide evidence that a problem exists in relation to a specified group of product or service users; it cannot be a matter of opinion. What follows is a line of reasoning for a project by Jessye Holmgren-Sidell that prototypes a physical toolkit, which facilitates parent-child reading of picture books for children with profound visual impairments.[39]

“Picture books can facilitate preschool children’s literacy comprehension and ability to retain information [...].[40] Through interactive reading with their parents, children begin to internalize the illustrations they see in stories and apply them to real-life experiences [...].[41] As a visual means of conceptualization and communication [...],[42] picture books offer an array of potential benefits to young readers, but exclude those readers with visual impairments.”[43]

This establishes the value of the subsequent investigation. Evidence for the importance of parent-child reading with picture books is derived from the literature rather than the designer’s beliefs: “Bishop [...] also recommends early intervention for children with visual impairments, noting that parent and teacher-provided interactive experiences (e.g., tactile explorations) can help with their concept and cognitive development.”[44]

Hernon and Schwartz provide attributes of a problem statement, as well as a brief exercise taken from David Clark for conceptualizing a problem statement before writing it in full,[45] which I assign in the thesis preparation course. Three sentences are drafted: a lead-in, a statement about originality that also identifies what an investigation will “do,” and a justification.[46] These statements can then be expanded into document sections that are supported by the literature.

Relevance

The criterion of relevance necessitates that the investigation is situated within a larger research context, and that its stated problem can be addressed, at least in part, through design. This is accomplished through the justification. Relevance requires opportunism.

The designer must find either a gap in the literature or an opportunity to apply existing theory to a new situation. For instance, the picture book reading toolkit meets a need that was not previously well understood: “There is currently no extensive system that young children with visual impairments and their parents can apply to a range of existing picture books to make them both accessible and interactive reading experiences.”[47]

The justification requires that the student articulates why design has “something to say” in relation to the problem. The first document section students complete in the thesis preparation course is an analysis of design precedents, which helps them formulate the justification.

Novelty

The criterion of novelty necessitates that the investigation synthesizes theory from more than one area, ensuring that studies will not be redundant with previous work. This is accomplished through a visualized conceptual framework, which (if novel) represents a contribution even before the studies are undertaken. Novelty requires analysis.

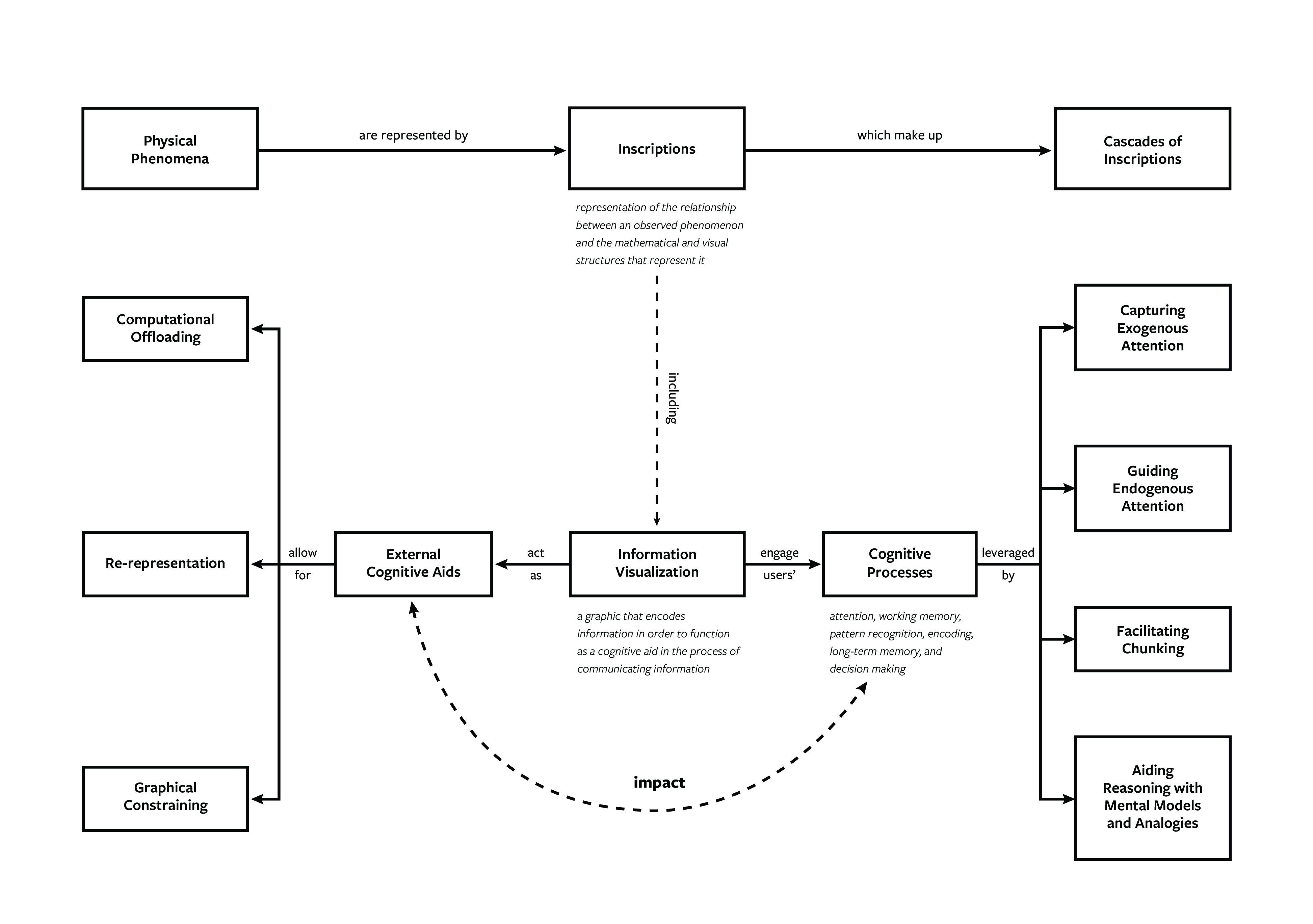

Figure 5 reproduces a conceptual framework from a project on the perception of uncertainty in data visualization by Mac Hill.[48] It synthesizes theories from three sources,[49] and is subsequently related to another source on the nature of uncertainty.[50] The conceptual framework exposes the designer’s own conceptualization as formed by a review of literature. It gives structure to the relevant literature in relation to the problem.

The degree to which the investigation is valuable, relevant, and novel is established in project definition and precedes design activity. The degree to which the investigation is focused, transferable, and practicable — the remaining criteria — is determined by the unique contribution of design as a mode of exploration. This exploration is formalized in a coordinated series of visual and interactive studies.

Focus

The criterion of focus necessitates that the studies are predicated on, and can be interpreted in relation to, declared gaps in knowledge. This is accomplished through structured research questions, which target those gaps and must precede the studies. Focus in the studies requires an initial clarity of purpose.

Research questions guide the researcher’s design activity, suggesting “methodological and philosophical approaches” while identifying the people, concepts, and circumstances under study.[51] Research questions are crucial for guiding research practices in the social sciences. Davis provides criteria for “good” research questions in the context of design, including the implication of a hierarchy in aspects of the problem, definition of terms, reliance on a working theory, establishment of realistic scope, and anticipation of how and by whom any findings will be used.[52] An analysis of academic research in the U.K. in 2014 found graphic design research to be “generically weak,”[53] and a subsequent analysis by Corazzo and colleagues emphasized the typical absence of research questions in graphic design research statements.[54] Their recommendations for academics include a “clearer focus upon identifying and addressing specific research questions.”[55] Research questions are thus not a given in design, and students need support in constructing them.

Design-based discovery is increasingly formulaic in how it structures research questions: one primary research question is followed by three or four “subquestions.” [d] In the social sciences, evidence can be built to “answer” such questions. As a discovery phase only — not part of theory testing — design-based discovery does not consider responses to the questions as answers, but more speculatively as explorations, though such responses are rigorous.

The primary question is never directly addressed, its scope being broad. Instead, it declares fundamental intent and leads to subquestions, which, in contrast, can be acted upon directly, and have a scope that is appropriate to design exploration. In design-based discovery, the primary question must declare all of, and the subquestions some of, five elements:

- People: whom the investigation benefits and what is particular about them.

- Technology: what is being prototyped, or what the people will use.

- Setting: how the people will interact with the technology, or under what conditions this interaction will occur.

- Outcome: what will be accomplished by the operation of the technology for the people.

- Means: how the operation of the technology will accomplish the outcome.

The relationship of outcome to means, and of those elements to the problem itself, is logical and supported by established knowledge from the literature. For instance, the outcome–means relationships threading the subquestions to the primary question in the visual impairment picture book toolkit include movement of tokens by hand in order to model actions visualized in picture books, which helps children construct event and scene schemas, which in turn facilitates literacy comprehension (the problem statement establishes the value of literacy comprehension for child development). [e] In this thread, “which” indicates an assertion supported by the literature. The designerly task is to demonstrate a range of actions that might be modeled with tokens.

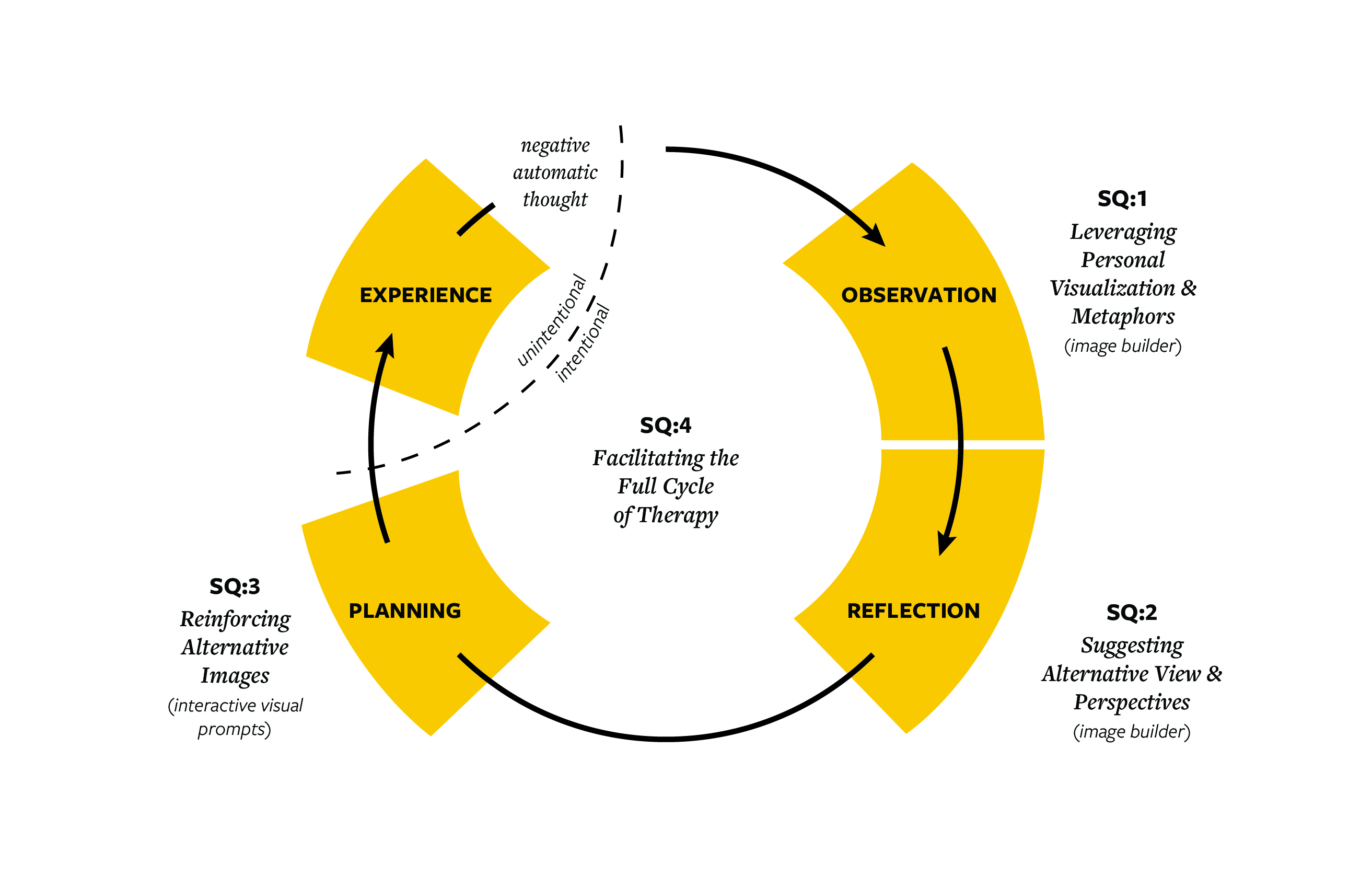

Ashley Anderson[56] was interested in digitally mediating cognitive behavioral therapy,[57] which usually takes the form of an exercise in a therapist’s office, helping a patient identify and challenge negative thoughts, and then to consider alternative thoughts. Anderson’s primary question and subquestions together demonstrate the requisite specificity for guiding design exploration:

How can a digital therapy tool challenge negative automatic thoughts for undergraduate students experiencing anxiety in order to achieve more balanced thinking in daily planning and goal setting?

- How can a multimodal image builder leverage unique personal visualizations and metaphors to help students new to metacognition represent their thoughts through imagery?

- How can a multimodal image builder suggest alternative views or perspectives to help students identify and reframe negative automatic thoughts?

- How can interactive visual prompts interrupt negative thinking patterns to help students practice using alternative thoughts and images to manage their goals in high and low-stress moments?[58]

Because research question development is both important and difficult for students, I assign brief exercises that require declarations of the individual elements of the questions (e.g., outcome, means). These exercises are not framed as being related to research questions, which helps the students to focus on possibilities and relationships without being overburdened by the research question structure. When students are ultimately asked to construct formal research questions, they already have options for structuring the requisite elements that they can combine.

Transferability

The criterion of transferability necessitates that design exploration takes the form of successively scheduled studies. Studies must be coordinated to prove instructive for other situations in aggregate and beyond each study’s own idiosyncrasies. This is accomplished through the investigation model, which determines and guides the studies. Transferability requires disciplined variability.

Even well-formulated research questions can fail to guide design exploration. To give actionable direction to studies, an investigation model organizes the subquestions into what are effectively small project briefs. Each subquestion represents a distinct prompt for design exploration. There is always theoretically justified guidance for the designer to vary the studies. For instance, in Hill’s uncertainty in data visualization project[59] four of six leverage points that influence the cognitive power of information visualizatio[60] (e.g., capture exogenous attention) map onto four subquestions and form one axis of the investigation model, which is manifest as a matrix (see Table 2)[61] The secondary axis, represented in an additional subquestion, relates those leverage points to four types of uncertainty in dat[62] (e.g., disagreement uncertainty). Each cell in the resulting investigation model suggests a unique study. Meaningful comparisons across studies placed in rows or columns transcend what are individually anecdotal studies into disciplined variability. Of note, the systematic relation of theoretical constructs speaks the language of the variable in the social sciences.

It is also possible to employ the investigation model in a project more concerned with a singular prototype, as in the visual impairment picture book toolkit project. The distinction is that in such investigations each subquestion derives its suggested variability from some distinct theoretical construct, and variability occurs in the exploration of one feature at a time — the designer explores different forms and functions of specific features. In either case, the variation of studies is considered more valuable and transferable than any solution the designer might subjectively consider best.

The investigation model need not take matrix form. Anderson provides an example that clarifies the distinction of conceptual framework and investigation model, while presenting the latter in diagrammatic form.[63] The conceptual framework (Figure 6) organizes the concepts on which the investigation is based,[64] but it is the investigation model (Figure 7) that directly addresses what will be executed through design exploration. The investigation model describes the cognitive behavioral therapy cycle and maps the studies onto the stages of the cycle that they address as features within a system. It is also clear, as labeled, that the subquestions correspond to the studies.

Practicability

The criterion of practicability necessitates that any tentative results can be used by other researchers. This is accomplished through the studies and a subsequent discussion. Practicability requires pattern finding that results in the articulation of design principles.

It is incumbent upon the designer to derive principles from the visual and interactive studies. It is these principles that render the investigation practicable, with the studies ultimately serving as mere examples of those principles in action. The derivation of principles requires pattern finding — a noted skill of designer[65] — that must be made evident to others through a discussion chapter in the written document. It is crucial, however, that the disciplined variability of studies be documented, so that others might derive principles that the designer has overlooked. The principles must be considered provisional before they could, sometime in the future, become subject to evidence-based interrogation.

Marcie Laird explored the mediation of remote health information sharing between a midwife and a rural expectant mother during the mother’s first pregnancy.[66] This included: visual aids meant to increase the patient’s agency during storytelling of their lived experience; interactive prompts meant to develop a shared understanding of the patient’s social and emotional health determinants; and self-reflective image generation meant to increase the validity of information shared between visits from the midwife.[67] Laird used what she learned from engaging in this investigation to articulate ten principles, including the following three.

- Visual disclosure: The formal qualities of visual aids affect the perceived privacy of the information embedded within them.

- Collaborative presence: In a shared digital space, a participant’s use of visual tools is influenced by the perceived presence of their collaborator.

- Visual appropriateness: The form of imagery used to mediate dialogue should reflect the tone and content of the information shared.[68]

The first “visual disclosure” principle is related to trust-building as follows.

“Visual aids that are abstract in nature lend a heightened sense of control to the user, as their true meaning is difficult to ascertain without supplemental explanation. As a participant, they can exercise discretionary disclosure, making decisions about what is included in the image and what is left out. For example, when the patient constructs a cognitive map of their support network using emojis [here Laird references an earlier figure], this representation of their life is undoubtedly derivative. Their choice of emoji still carries information about their perceptions and emotional attachments, but this data is essentially inaccessible to the midwife without explanation [...], creating a sense of security for the participant.

“On the other hand, as images approach more realistic impressions of the participant’s life, the window for interpretation narrows, reducing their sense of privacy. The photographs used to capture memories between the patient and their partner [here another figure is referenced] put all the subtleties of their reality on display, making it difficult to “hide” behind abstract forms that muddle intention. These images demand a higher level of vulnerability on the part of the participant, in which they actively choose to sacrifice privacy for a more accurate representation of self. If a participant is asked to disclose information they perceive to be private too soon, their relationship with the caregiver may suffer. Therefore, the relationship between the form of visual tools and information disclosure should be carefully considered when employing imagery as a dialogic mediator.”[69]

The design principles are thus general but are explicitly linked by the designer to specific contextualized instances of design exploration.

Beyond even the derivation of principles, studies can be practicable when they anticipate use in research in the social sciences. Matthew Lemmond explored the serious virtual reality (VR) game as a platform for helping cancer patients reduce their psychological distress, particularly by utilizing embodied metaphors.[70] A literature review supplied authentic patients’ conceptualizations of cancer.[71] One subquestion prompted explorations of the qualities reported by those cancer patients, giving form to the data in the new context of VR.[72] This included both visual features (e.g., roundness, possession of appendages) and motion behaviors (e.g., floppiness). The resultant theoretically grounded representational prescriptions could readily be adopted by researchers in the social sciences as they conduct experiments to determine how representations of cancer might feel more intuitive to subjects, or to adopt as standards for applied research on the effects of a particular VR intervention with cancer patients. There are thus multiple ways to increase practicability.

Focus, transferability, and practicability are achieved in a concerted effort through the research questions, investigation model, and design principles as derived from the studies. The criteria described here address the subjectivity inherent in design exploration, leveraging designers’ inherent strengths while systematically and rigorously guiding design activity.

Prerequisite Student Experiences

The thesis project in N.C. State’s Master of Graphic Design program requires student competencies that are implicit in the program’s objectives. These objectives include, among others:

- Students will demonstrate depth of knowledge about emergent technologies and related design issues through a body of studio-based work that is speculative, propositional, and inventive.

- Student work will demonstrate knowledge of the consequences of students’ design in and among social, cultural, and technological systems and for users in their physical activities.

- Students will acquire design research methods that support collaborative work and engage people.

- Students will apply existing theoretical frameworks from a range of disciplines, including design, and judge their appropriateness to design research and inquiry.

- Students will demonstrate knowledge of different precedents and modes of inquiry from design and related fields in their studio work and writing.

Fulfillment of these objectives — and thus of the thesis itself — is dependent upon established coursework and institutional infrastructure. A thesis preparation course in the third of four semesters facilitates the student’s definition of project parameters. Students leave this course having written three of five chapters of the thesis document: Introduction, Problem Space, and Investigation Plan. In the final semester, students engage in design exploration in the form of visual and interactive studies, as guided by the research questions and investigation model, and they write the final two chapters of the thesis document: Studies and Discussion. Each chapter and section of the document has a recommended word count (altogether totaling 6,000–12,000 words). Throughout direct work on the thesis, students meet regularly with their respective thesis committee chairs and occasionally with their full three-member committees of graduate faculty. This support system and a shared schedule is invaluable.

Students must be capable designers, and this is ensured through admissions, a sequence of three intensive studios, and a Research Methods in Design course. This methods course covers human-centered and user experience design, roughly representative of the best practices of normal design.

A New Information Environments course covers the societal and disciplinary implications of recent and developing technology, while also extending students’ writing skills. A Conceptual Frameworks for Designers course organizes knowledge bases in the literature into theories of doing, thinking, feeling, and meaning; introduces students to the literature review; reveals the underlying structures of academic writing in the social sciences; and requires students to synthesize literature into frameworks. These courses are foundational in the students’ ability to produce the problem statement, justification, conceptual framework, and principles. The thesis preparation course builds on familiarity with structures of academic writing to help students draft research questions and construct an investigation model. A series of brief workshop exercises is provided to students who wish to begin defining their theses in the summer before the final year. Some of these exercises are also incorporated into the thesis preparation course.

The graduate faculty who serve on thesis committees and oversee the prerequisite coursework all maintain research practices. They recognize much of the literature the students locate through searches, and are able to suggest further literature or recommend strategies for finding it. North Carolina State University is a “very high research activity” doctoral university (Carnegie Classification), and thus has a robust library system with digital access to most academic journals. Without such access, this model of design inquiry would not be achievable, suggesting that design-based discovery can only be one model among others of master’s programs in design, as many degree-granting programs do not have the same resources.

Discussion

Design cannot be overly prescriptive, yet design exploration must be rigorous if it is to have a role in relation to evidence-based inquiry. The academic model of design inquiry described here places design exploration within a broader theory development cycle, while other models tend to exclude design or assume it can stand in for the full cycle. Situating design within the evidence-based inquiry of the social sciences makes design essential to broader activities in and purposes of the academic setting. Of course, cogent arguments can be made for other models of design research and other conceptions of design’s place in broader practices of inquiry. Each model will have its own benefits and limitations.

Design-based discovery scaffolds a role for designers within the social sciences. It retains what is inherent to design as a practice of exploratory production and abductive reasoning,[73] while also demanding that designers adapt their design exploration to knowledge structures in the social sciences and produce outcomes that are conducive to further investigation of variables, not singular solutions. Deriving principles from the work requires induction, or reasoning from the specific to the general. Designers already learn to think inductively, particularly in critique, and are well prepared to make such contributions. If designers do not in some way adapt to other research paradigms — without, of course, ceasing to be designers — they cannot as readily contribute to the ongoing generation of knowledge otherwise occurring across disciplines.

Certain features of design-based discovery distinguish it from solution-based design activity while aligning it with research practices in the social sciences. First, the designer finds and interprets ideas and frameworks from literature not limited to design. Following judgments of efficacy for the project at hand, the designer synthesizes sources of information to construct or define an investigation. In relation to the outcome and means elements of research questions previously discussed, the investigation as defined can be considered an outcome–means construct, which is grounded in knowledge from multiple disciplines. From this point, the designer is engaged in normal design (i.e., best practices of design activity), producing a range of “solution-conjectures”[74] and possibly, but not necessarily, making formal decisions to develop a prototype. Thus, the exploratory phase represents an expansion of possibilities, while an optional prototype phase represents a contraction or closing down of possibilities. Finally, in a deviation from normal design, principles are derived from the earlier solution-conjectures, not a solution. Through the rigors of design-based discovery, these principles maintain a connection back to the established knowledge upon which the endeavor was based. Because there is continuity from the literature to the form of design exploration, the studies — both iterations and abandoned directions — become boundary objects[75] interpretable in distinct ways by disciplinary communities. It is through these boundary objects that experts in other disciplines may come to see possibilities even the designer has overlooked.

I have outlined a model of design inquiry where design exploration serves as a research discovery phase. This model guides design activity in order to make a special contribution in areas of the social sciences otherwise external to design. This involves a careful process with six investigation components, all ultimately connecting knowledge bases outside of design to design exploration. The model is humble in placing design activity within broader evidence-based research practices. It makes no claim that a designer’s self-reflection is equal to the rigorous methods of the social sciences. Design researchers should continue to study design and build the discipline’s own knowledge, but this need not mean that designers also separate themselves from other important areas of inquiry that are highly valued at research universities.

Acknowledgments

While all those who have served as graduate faculty in the Master of Graphic Design program at North Carolina State University have contributed to the development of this model of design inquiry, Meredith Davis and Deborah Littlejohn were particularly instrumental, having taught previous offerings of the thesis preparation course. Littlejohn recently developed and continues to oversee the course on frameworks, without which this model could not have matured. Helen Armstrong’s discussion-based course on technology and her sponsored studios (which engage students in industry-oriented research), as well as Denise Gonzales Crisp’s repeated studios that stage speculative making, enable the model’s operation. Gonzales Crisp has also been the director of the Master of Graphic Design program during the model’s development. The students who have participated in the formal thesis process, especially over the past four years, have also helped to develop design-based discovery.

Biography

Matthew Peterson ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of Graphic Design at North Carolina State University, where he teaches and advises in the Master of Graphic Design and Ph.D. in Design programs. He is co-principal investigator, in a multidisciplinary collaboration with researchers in Industrial & Systems Engineering and STEM Education, of a recently awarded NSF grant: “Virtual Reality to Improve Students’ Understanding of the Extremes of Scale in STEM” (#2055680). His active work includes: the NSF-funded development of a virtual environment for learning scale and scientific numeracy; identification and development of alternative visualization strategies in science curriculum materials; eye tracking for studying visual displays in science learning; and eye tracking for processing visual metaphor in advertisements.

References

- Akimoto, T. “Narrative Structure in the Mind: Translating Genette’s Narrative Discourse Theory into a Cognitive System.” Cognitive Systems Research 58 (2019): pgs. 342–350.

- Anderson, A. Working with Imagery: Mediating Image Rescripting for Anxiety with Multimodal Digital Storytelling (graduate thesis). Raleigh, NC, USA: North Carolina State University, 2020.

- Archer, B. “The Nature of Research.” Co-Design (January, 1995): pgs. 6–13.

- Bayazit, N. “Investigating Design: A Review of Forty Years of Design Research.” Design Issues 20.1 (2004): pgs. 16–29.

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. New York, NY, USA: International Universities Press, 1976.

- Bishop, V.E. Preschool Children with Visual Impairments. Austin, TX, USA: Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, 1996.

- Buchanan, R. “Design Research and the New Learning.” Design Issues 17.4 (2001): pgs. 3–23.

- Buchanan, R. “Thinking about Design: An Historical Perspective,” in Philosophy of Technology and Engineering Sciences, edited by John Woods, pgs. 409–453. Amsterdam, NL: North Holland Publishing Co., 2009.

- Candy, L. Practice Based Research: A Guide. Sydney, AU: Creativity & Cognition Studios, 2006.

- Candy, L., & Edmonds, E. “Practice-Based Research in the Creative Arts: Foundations and Futures from the Front Line.” Leonardo 51.1 (2018): pgs. 63–69.

- Cash, P.J. “Developing Theory-Driven Design Research.” Design Studies 56 (2018): pgs. 84–119.

- Corazzo, J., Harland, R.G., Honnor, A., & Rigley, S. “The Challenges for Graphic Design in Establishing an Academic Research Culture: Lessons from the Research Excellence Framework 2014.” The Design Journal 23.1 (2020): pgs. 7–29.

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches – Second Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications, 2003.

- Cross, N. “Designerly Ways of Knowing.” Design Studies 3.4 (1982): pgs. 221–227.

- Cross, N. “Design Research: A Disciplined Conversation.” Design Issues 5.2 (1999): pgs. 5–10.

- Cross, N. Designerly Ways of Knowing. London, UK: Springer-Verlag, 2006.

- Cross, N. “Editorial: Forty Years of Design Research.” Design Studies 28 (2007): pgs. 1–4.

- Davis, M. “Why Do We Need Doctoral Study in Design?” International Journal of Design 2.3 (2008): pgs. 71–79.

- Davis, M. “Leveraging Graduate Education for a More Relevant Future.” Visible Language 46.1/2 (2012): pgs. 111–121.

- Davis, M. “What Is a ‘Research Question’ in Design?,” in The Routledge Companion to Design Research, edited by Paul A. Rogers & Joyce Yee, pgs. 132–141. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2015.

- Davis, M. “Tenure and Design Research: A Disappointingly Familiar Discussion.” Design and Culture 8.1 (2016): pgs. 123–131.

- Davis, M. “Confronting the Limitations of the MFA as Preparation for Ph.D. Study.” Leonardo 53.2 (2020): pgs. 206–212.

- Dixon, B. “Experiments in Experience: Towards an Alignment of Research through Design and John Dewey’s Pragmatism.” Design Issues 35.2 (2019): pgs. 5–16.

- Dorst, K., & Dijkhuis, J. “Comparing Paradigms for Describing Design Activity.” Design Studies 16 (1995): pgs. 261–274.

- Epstein, S. “Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory of Personality,” in Handbook of Psychology: Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 5, edited by Theodore Millon, Melvin J. Lerner, & Irving B. Weiner, pgs. 159–184. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003.

- Fang, Z. “Illustrations, Text, and the Child Reader: What Are Pictures in Children’s Storybooks For?” Reading Horizons 37.2 (1990): pgs. 130–142.

- Fisher, E., Lee, N., & Thompson-Whiteside, S. “Same But Different: A Framework for Understanding Conceptions of Research in Communication Design Practice and Academia.” Visible Language 52.2 (2018): pgs. 56–81.

- Frayling, C. “Research in Art and Design.” Royal College of Art Research Papers 1.1 (1993): 1–5.

- Giaccardi, E. “Histories and Futures of Research through Design: From Prototypes to Connected Things.” International Journal of Design 13.3 (2019): pgs. 139–155.

- Green, H., & Powell, S. “Practice-Based Doctorates,” in Doctoral Study in Contemporary Higher Education, pgs. 100–118. New York, NY, USA: Open University Press, 2005.

- Harrow, A., Wells, M., Humphris, G., Taylor, C., & Williams, B. “Seeing Is Believing, and Believing Is Seeing: An Exploration of the Meaning and Impact of Women’s Mental Images of Their Breast Cancer and their Potential Origins.” Patient Education and Counseling 73.2 (2008): pgs. 339–346.

- Herman, D. “Cognitive Narratology.” The Living Handbook of Narratology (2013), https://www.lhn.uni-hamburg.de/node/38.html (accessed October 19, 2019).

- Herman, D. Storytelling and the Sciences of Mind. Cambridge, MA, USA: The MIT Press, 2013.

- Hernon, P., & Schwartz, C. “Editorial: What Is a Problem Statement?” Library & Information Science Research 29 (2007): pgs. 307–309.

- Hill, M. Visualizing Uncertainty: Developing an Experiential Language for Uncertainty in Data Journalism (graduate thesis). Raleigh, NC, USA: North Carolina State University, 2018.

- Holmgren-Sidell, J. Conceptualize This: Making Picture Books Accessible for Preschool Children with Visual Impairments (graduate thesis). Raleigh, NC, USA: North Carolina State University, 2019.

- Josefowitz, N. “Incorporating Imagery into Thought Records: Increasing Engagement in Balanced Thoughts.” Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 24.1 (2017): pgs. 90–100.

- Kaplan, A. The Conduct of Inquiry: Methodology for Behavioral Science. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 1998.

- Kress, G.R. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London, UK: Routledge, 2010.

- Laird, M. Dialogic Imagery for Care: Visual Mediation of Complex Conversations in Alternative Prenatal Caregiving. Manuscript draft (protected google doc): April 8, 2021.

- Lee, A.S., & Baskerville, R.L. “Generalizing Generalizability in Information Systems Research.” Information Systems Research 14.3 (2003): pgs. 221–243.

- Lemmond, M.D. Helping Cancer Patients Reduce Psychological Distress with Embodied Conceptual Metaphors in a Serious VR Game (graduate thesis). Raleigh, NC, USA: North Carolina State University, 2019.

- Littlejohn, D. “Disciplining the Graphic Design Discipline: The Role of External Engagement, Mediating Meaning, and Transparency as Catalysts for Change.” Art, Design, & Communication in Higher Education 16.1 (2017): pgs. 33–51.

- Martin, R.L. The Design of Business: Why Design Thinking Is the Next Competitive Advantage. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2009.

- Patterson, R.E., Blaha, L.A., Grinstein, G.G., Liggett, K.K., Kaveney, D.E., Sheldon, K.C., Havig, P.R., & Moore, J.A. “A Human Cognition Framework for Information Visualization.” Computers & Graphics 42 (2014): pgs. 42–58.

- Pedgley, O. “Capturing and Analyzing Own Design Activity.” Design Issues 28 (2007): pgs. 463–483.

- Pedgley, O., & Wormald, P. “Integration of Design Projects within a Ph.D.” Design Issues 23.3 (2007): pgs. 70–85.

- Research Excellence Framework (REF). Research Excellence Framework 2014: Overview Report by Main Panel D and Sub-Panels 27 to 36 (January, 2015). https://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/media/ref/content/expanel/member/Main%20Panel%20D%20overview%20report.pdf (accessed April 8, 2021).

- Roth, W.M., & Tobin, K. “Cascades of Inscriptions and the Re-Presentation of Nature: How Numbers, Tables, Graphs, and Money Come to Re-Present a Rolling Ball.” International Journal of Science Education 19.9 (1997): pgs. 1075–1091.

- Rozental, A., Bennett, S., Forsström, D., Ebert, D.D., Shafran, R., Andersson, G., & Carlbring, P. “Targeting Procrastination Using Psychological Treatments: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in Psychology 9.1588 (2018): pgs. 1–15.

- Rust, C., Mottram, J., & Till, J. Review of Practice-Led Research in Art, Design, & Architecture. Sheffield, UK: Arts and Humanities Research Council, 2007.

- Scaife, M., & Rogers, Y. “External Cognition: How do Graphical Representations Work?” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 45.2 (1996): pgs. 185–213.

- Shulevitz, U. Writing with Pictures: How to Write and Illustrate Children’s Books. New York, NY, USA: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1985.

- Skeels, M., Lee, B., Smith, G., & Robertson, G. “Revealing Uncertainty for Information Visualization.” AVI ’08 Proceedings of the Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces 45.2 (2008): pgs. 376–379.

- Star, S.L. “The Structure of Ill-Structured Solutions: Boundary Objects and Heterogeneous Distributed Problem Solving,” in Distributed Artificial Intelligence, Volume II, edited by Les Gasser & Michael N. Huhns, pgs. 37–54. London, UK: Pitman Publishing, 1989.

- Strouse, G.A., Nyhout, A., & Ganea, P.A. “The Role of Book Features in Young Children’s Transfer of Information from Picture Books to Real-World Contexts.” Frontiers in Psychology 9.50 (2018): pgs. 1–14.

- Yang, Y.F. “Multimodal Composing in Digital Storytelling.” Computers and Composition 29.3 (2012): pgs. 221–238.

- Zimmerman, J., Forlizzi, J., & Evenson, S. “Research through Design as a Method for Interaction Design Research in HCI.” CHI 2007 Proceedings: Design Theory (2007): pgs. 493–502.

Notes

- a

The social sciences is often differentiated from the humanities according to those disciplines one or the other includes in its scholarly purview, which is not particularly helpful (at least to designers), as these disciplines are inconsistently placed across listings. The simple Oxford Languages definition of social science, on the other hand, aligns with my usage and is appropriately fuzzy: “the scientific study of human society and social relationships” (emphasis added). [As of July, 2021, definitions displayed in both Google searches and Apple’s Dictionary are drawn from the Oxford Languages dictionary, which differs from the Oxford English Dictionary.] I emphasize “scientific” to undergird social science—or a fuzzy-bordered subdivision of social science I focus on here—with postpositive knowledge claims. Research design theorist John Creswell describes postpositivism as, “a deterministic philosophy in which causes probably determine effects or outcomes,” and relates it to the scientific method [Creswell, Research Design, pg. 7]. My sense of social science is consistent with the quantitative and imperfectly objective study of phenomena associated with postpositivism, as well as the more pragmatic use of mixed methods that also incorporates qualitative data collection to triangulate with quantitative data [pgs. 3–23]. When I use the term the social sciences, I am referring to what some would consider a subset of the social sciences, while others would consider it to be the social sciences in its entirety.

- b

Archer himself addressed this tendency in his 1995 paper [“The Nature of Research,” pg. 10.]: “In fact, some artists and designers, and some other creative practitioners, claim that what they ordinarily do is research.”

- c

In its alignment with evidence-based inquiry, design-based discovery is grounded in a postpositivist paradigm, which holds that “there are laws or theories that govern the world, and these need to be tested or verified so that we can understand the world” [Creswell, Research Design, pg. 7]. However, such testing and verification is subsequent to design-based discovery.

- d

Alternatively, the primary research question could be articulated as a “research objective,” in which case the subquestions would simply be “research questions.” While this may be more consistent with other research models—and though I would recommend it in future adoptions of design-based discovery—I am reporting the two-tiered research question structure that has been employed to date in N.C. State’s Master of Graphic Design program.

- e

Holmgren-Sidell, Conceptualize This, pg. 19; though the terminology used here comes from a developmental manuscript and the final manuscript has slightly different terminology.

Davis, M., “Confronting the Limitations of the MFA as Preparation for Ph.D. Study,” Leonardo 53.2 (2020): pgs. 206–212.

Fisher, E., Lee, N., & Thompson-Whiteside, S., “Same But Different: A Framework for Understanding Conceptions of Research in Communication Design Practice and Academia,” Visible Language 52.2 (2018): pgs. 61–62.

Littlejohn, D., “Disciplining the Graphic Design Discipline: The Role of External Engagement, Mediating Meaning, and Transparency as Catalysts for Change,” Art, Design, & Communication in Higher Education 16.1 (2017): pgs. 33–51.

Davis, M., “Tenure and Design Research: A Disappointingly Familiar Discussion,” Design and Culture 8.1 (2016): pgs. 123–131

Littlejohn, “Disciplining the Graphic Design Discipline,” pg. 36.

Davis, M., “Why Do We Need Doctoral Study in Design?,” International Journal of Design 2.3 (2008): pgs. 71–79; Davis, M., “Leveraging Graduate Education for a More Relevant Future,” Visible Language 46.1/2 (2012): pgs. 111–121; Davis, “Tenure and Design Research”; Davis, “Confronting the Limitations of the MFA.”

Corazzo, J., Harland, R.G., Honnor, A., & Rigley, S., “The Challenges for Graphic Design in Establishing an Academic Research Culture: Lessons from the Research Excellence Framework 2014,” The Design Journal 23.1 (2020): pgs. 7–29.

Corazzo et al., “The Challenges for Graphic Design,” pg. 20.

E.g., Bayazit, N., “Investigating Design: A Review of Forty Years of Design Research,” Design Issues 20.1 (2004): pgs. 16–29; Buchanan, R., “Thinking about Design: An Historical Perspective,” in Philosophy of Technology and Engineering Sciences, edited by John Woods, pgs. 409–453 (Amsterdam, NL: North Holland Publishing Co., 2009); Cross, N., “Editorial: Forty Years of Design Research,” Design Studies 28 (2007): pgs. 1–4; Dorst, K., & Dijkhuis, J., “Comparing Paradigms for Describing Design Activity,” Design Studies 16 (1995): pgs. 261–274.

Ball and Christensen 2019; Cross, N., “Design Research: A Disciplined Conversation,” Design Issues 5.2 (1999): pgs. 5–10; Cross, “Forty Years of Design Research”; Buchanan, R., “Design Research and the New Learning,” Design Issues 17.4 (2001): pgs. 3–23.

Archer, B., “The Nature of Research,” Co-Design (January, 1995): pgs. 6–13; Candy, L., Practice Based Research: A Guide (Sydney, AU: Creativity & Cognition Studios, 2006); Candy, L., & Edmonds, E., “Practice-Based Research in the Creative Arts: Foundations and Futures from the Front Line,” Leonardo 51.1 (2018): pgs. 63–69; Giaccardi, E., “Histories and Futures of Research through Design: From Prototypes to Connected Things,” International Journal of Design 13.3 (2019): pgs. 139–155; Green, H., & Powell, S., “Practice-Based Doctorates,” in Doctoral Study in Contemporary Higher Education, pgs. 100–118 (New York, NY, USA: Open University Press, 2005); Rust, C., Mottram, J., & Till, J., Review of Practice-Led Research in Art, Design, & Architecture (Sheffield, UK: Arts and Humanities Research Council, 2007).

Pedgley, O., “Capturing and Analyzing Own Design Activity,” Design Issues 28 (2007): pgs. 463–483.

Frayling, C., “Research in Art and Design,” Royal College of Art Research Papers 1.1 (1993): 1–5.

Cash, P.J., “Developing Theory-Driven Design Research,” Design Studies 56 (2018): pgs. 84–119.

Dixon, B., “Experiments in Experience: Towards an Alignment of Research through Design and John Dewey’s Pragmatism,” Design Issues 35.2 (2019): pg. 7.

Kaplan, A., The Conduct of Inquiry: Methodology for Behavioral Science (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 1998).

Zimmerman, J., Forlizzi, J., & Evenson, S., “Research through Design as a Method for Interaction Design Research in HCI,” CHI 2007 Proceedings: Design Theory (2007): pg. 499.

Pedgley, O., & Wormald, P., “Integration of Design Projects within a Ph.D.,” Design Issues 23.3 (2007): pg. 77.

Lee, A.S., & Baskerville, R.L., “Generalizing Generalizability in Information Systems Research,” Information Systems Research 14.3 (2003): pgs. 221–243.

Holmgren-Sidell, J., Conceptualize This: Making Picture Books Accessible for Preschool Children with Visual Impairments (Raleigh, NC, USA: North Carolina State University, 2019).

Original citation: Fang, Z., “Illustrations, Text, and the Child Reader: What Are Pictures in Children’s Storybooks For?,” Reading Horizons 37.2 (1990): pgs. 130–142; Strouse, G.A., Nyhout, A., & Ganea, P.A., “The Role of Book Features in Young Children’s Transfer of Information from Picture Books to Real-World Contexts,” Frontiers in Psychology 9.50 (2018): pgs. 1–14.

Original citation: Strouse et al., “The Role of Book Features.”

Original citation: Shulevitz, U., Writing with Pictures: How to Write and Illustrate Children’s Books (New York, NY, USA: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1985).

Holmgren-Sidell, Conceptualize This, pgs. 15–16; citing: Bishop, V.E., Preschool Children with Visual Impairments (Austin, TX, USA: Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, 1996).

Hernon, P., & Schwartz, C., “Editorial: What Is a Problem Statement?,” Library & Information Science Research 29 (2007): pgs. 307–309.

Hill, M., Visualizing Uncertainty: Developing an Experiential Language for Uncertainty in Data Journalism (Raleigh, NC, USA: North Carolina State University, 2018), pg. 26.

Patterson, R.E., et al., “A Human Cognition Framework for Information Visualization,” Computers & Graphics 42 (2014): pgs. 42–58; Scaife, M., & Rogers, Y., “External Cognition: How do Graphical Representations Work?,” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 45.2 (1996): pgs. 185–213; Roth, W.M., & Tobin, K., “Cascades of Inscriptions and the Re-Presentation of Nature: How Numbers, Tables, Graphs, and Money Come to Re-Present a Rolling Ball,” International Journal of Science Education 19.9 (1997): pgs. 1075–1091.

Skeels, M., Lee, B., Smith, G., & Robertson, G., “Revealing Uncertainty for Information Visualization,” AVI ’08 Proceedings of the Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces 45.2 (2008): pgs. 376–379.

Davis, M., “What Is a ‘Research Question’ in Design?,” in The Routledge Companion to Design Research, edited by Paul A. Rogers & Joyce Yee, pgs. 132–141 (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2015), pg. 135.

Research Excellence Framework (REF), Research Excellence Framework 2014: Overview Report by Main Panel D and Sub-Panels 27 to 36 (January, 2015), pg. 85.

Corazzo et al., “The Challenges for Graphic Design,” pg. 23.

Corazzo et al., “The Challenges for Graphic Design,” pg. 26.

Anderson, A., Working with Imagery: Mediating Image Rescripting for Anxiety with Multimodal Digital Storytelling (Raleigh, NC, USA: North Carolina State University, 2020), pg. 3.

Rozental, A., et al., “Targeting Procrastination Using Psychological Treatments: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Frontiers in Psychology 9.1588 (2018): pgs. 1–15.

Skeels et al., “Revealing Uncertainty for Information Visualization.”

Citations: Akimoto, T., “Narrative Structure in the Mind: Translating Genette’s Narrative Discourse Theory into a Cognitive System,” Cognitive Systems Research 58 (2019): pgs. 342–350; Beck, A.T., Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders (New York, NY, USA: International Universities Press, 1976); Epstein, S., “Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory of Personality,” in Handbook of Psychology: Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 5, edited by Theodore Millon, Melvin J. Lerner, & Irving B. Weiner, pgs. 159–184 (New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003); Herman, D., “Cognitive Narratology,” The Living Handbook of Narratology (2013), accessed October 19, 2019; Herman, D., Storytelling and the Sciences of Mind (Cambridge, MA, USA: The MIT Press, 2013); Josefowitz, N., “Incorporating Imagery into Thought Records: Increasing Engagement in Balanced Thoughts,” Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 24.1 (2017): pgs. 90–10; Kress, G.R., Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication (London, UK: Routledge, 2010); Yang, Y.F., “Multimodal Composing in Digital Storytelling,” Computers and Composition 29.3 (2012): pgs. 221–238.

Cross, N., “Designerly Ways of Knowing,” Design Studies 3.4 (1982): pg. 224.

Laird, M. Dialogic Imagery for Care: Visual Mediation of Complex Conversations in Alternative Prenatal Caregiving. Manuscript draft (protected google doc): April 8, 2021.

Lemmond, M.D., Helping Cancer Patients Reduce Psychological Distress with Embodied Conceptual Metaphors in a Serious VR Game (Raleigh, NC, USA: North Carolina State University, 2019).

Harrow, A., Wells, M., Humphris, G., Taylor, C., & Williams, B., “Seeing Is Believing, and Believing Is Seeing: An Exploration of the Meaning and Impact of Women’s Mental Images of Their Breast Cancer and their Potential Origins,” Patient Education and Counseling 73.2 (2008): pgs. 339–346.

Lemmond, Helping Cancer Patients Reduce Psychological Distress.

Martin, R.L., The Design of Business: Why Design Thinking Is the Next Competitive Advantage (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2009), pg. 74.

Cross, N., Designerly Ways of Knowing (London, UK: Springer-Verlag, 2006), pgs. 70–80.

Star, S.L., “The Structure of Ill-Structured Solutions: Boundary Objects and Heterogeneous Distributed Problem Solving,” in Distributed Artificial Intelligence, Volume II, edited by Les Gasser & Michael N. Huhns, pgs. 37–54 (London, UK: Pitman Publishing, 1989).