Toward a Critical Design Thinking: Propositions to Rewrite the Design Thinking Process

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Design thinking is often praised as a universal tool that can be utilized to address and resolve almost any design problem, even those that are the most complex. Judging by the recent criticism from several key design professionals, design thinking seems ill-suited to confront complex, or so-called ‘wicked’ problems or to facilitate deep thinking. Design thinking falls short of tackling these problems because it only provides ways to empathize with customers, rendering them passive bystanders in the innovation process. In order to address these shortcomings inherent in design thinking, the following discourse introduces deeper critical thinking skills into design thinking, allowing designers in combination with everyday experts to collectively form a political will and act on it. Borrowing from the critical design debate, the new critical design thinking processes developed in response to the growing need for designers to deploy deeper analytical skills to guide their decision-making provides a framework to guide a collective design practice capable of dealing with the complex, multi-faceted nature of current political, economic and social affairs. Rather than sustaining a focus on the development of products and product systems and the means to market them at large scale, designers must now work to shift their practice to create critical meta design tools aimed at solving complex design problems, such as circular design[a] or social design[b] challenges.

Introduction

Lately, the methods that guide design thinking processes have been more heavily scrutinized by design practitioners, educators and researchers who have come to understand that these methods often tend to be largely devoid of critical and deep thinking.[c] This is not new information for those who have followed recent academic discourse, since so many design scholars tend to think of design thinking as a somewhat hostile acquisition in terms of how and why it has been utilized in design consultancies, corporate innovation labs, consulting firms and management seminars.[d] Design thinking in the view of many design scholars is not just a one-size-fits-all design tool, but a term that comprises a variety of diverse design practices. Design scholar Richard Buchanan stressed that the more design opens up to social, ecological and political questions, the broader the practice and study of and research that informs design become.[1] Following Buchanan’s notion, it does not make sense to reduce the term design thinking to a set of specific user-centered methods outlined (for instance) in playbooks like “This is Service Design Thinking”[2] or “The Design Thinking Playbook”.[3] Design scholars like Nigel Cross, Wolfgang Jonas, and Charles Burnett, to name but a few, were some of the first to speak against the application of so normative a meaning being attached to the term design thinking.[4] Jonas, although acknowledging that decision-making processes guided by design thinking would allow the number of potential challenges that design could address to rise by a considerable amount, criticized the fact that design thinking did not effectively facilitate reflection on the specific nature of a given problem, and did not effectively foster a well-contextualized design process.[5]

As of this writing in the early summer of 2019, many design scholars continue to criticize and rethink the purpose of design thinking. For example, Paul A. Rodgers, Giovanni Innella, and Craig Bremner believe that design thinking needs to become more critical to allow it to provide designers and their collaborators with a viable means for dealing with the social, technological, economic and political paradoxes of a complex world, as well as its own paradoxical existence.[6] Lucy Kimbell criticizes current applications of design thinking for its lack of criticality and its sole focus on the designer as the dominant entity in the design process.[7] Most design scholars engage in near-constant critical academic discourse, and, in order to ensure that this discourse is imbued with a high level of critical rigor, it is only natural for them to place an approach to guiding design decision-making like design thinking under scrutiny. Despite this, only a few provide any type of tangible guidance about how to operationalize their vision of design thinking infused with broadly informed, critical interrogation.

The inadequacies of the methods to guide decision-making described by design thinking have led a number of professionals in the field (designers, design managers, and creative leaders) to question design thinking as a viable approach and turn away from it. The praise design thinking has received is based on it being utilized to provide a reliable framework for rapidly creating user-centered design ideas and solutions, but this does not seem to be working any longer. More and more design professionals are rejecting design thinking because so many of the methods that guide it do not accommodate critical thinking. In a recent conference presentation by Pentagram partner Natasha Jen, she stressed that “design criticism is completely missing from the design thinking steps,” and going on to further articulate that critical thinking takes a back seat to the methods that constitute design thinking. Moreover, Jen rejects claims that design thinking “can be applied by anyone to any problem” just because it relies on linearly applied methods. From her point of view, this seems highly problematic, and makes design thinking feel like “corporate jargon” rather than a practice that can be planned and operated in ways that meet the needs of designers.[8] Other design professionals deem design thinking to be a set of tools that fail to foster reflection, arguing that the rigid structure of design thinking eliminates it. Justin Maguire, Senior Vice President of Product Design and User Experience at Salesforce, expressed his rejection of the method when he explained that the failure of design thinking was rooted in the “idea that a process can stand in for really smart people.”[9] Similar to the critique expressed by Natasha Jen, Maguire couched his criticisms of design thinking in a common notion among professionals who utilize design thinking, namely that applying design thinking methods can effectively substitute for a broadly informed, deeply plumbed, critical reflection of the complexity inherent in a given design challenge. The criticisms offered by Jen and Maguire reveal one of the most common misconceptions about design thinking—that it is possible to contextualize, plan to and then resolve complex social, technological, economic and public policy problems by following a set of preconceived, methodologically finite instructions.

As many design practitioners, researchers and educators have come to know them, “design methods” were created to help designers at least begin to consider how their decision-making processes could be informed by building empathy for those who would be affected by what they designed. They were also supposed to help ensure that designers learned to work iteratively, to endeavor to generate and assess, and, as necessary, combine many ideas—as opposed to only a few—for making, doing and changing protocols and procedures. They informed processes that allowed designers to test ideas—often as prototypes—based on a broadly informed and deeply probative blending of heuristically informed processes and intuition. The Design Methods Movement was originally formulated by a small group of British design professionals and educators in their practices and classrooms in the 1960s and 1970s, and by a small group of design educators who incorporated these approaches into the courses they taught at the Ulm School of Design as early as the late 1950s.[e] These were then championed at a series of design conferences held in the U.K.[10] The core ideas that guided The Design Methods Movement considered them to be a desirable and effective support system for guiding the decision-making of designers. Instead of a messy design process that limited the results of good design to what could be achieved merely through trial and error, employing the newly articulated “design methods” could intellectually support and refine this process. Whereas The Design Methods Movement understood and sought to employ methodologies that were much more scientifically guided and comprehensively informed as a means to fundamentally inform the design process than had been practiced or taught previously, much of what now constitutes contemporary design methods described under the auspice of design thinking employs little of this. The methods that now tend to guide design decision-making according to design thinking tend to mimic ethnographic or other anthropological research methods that have been watered down to fit into corporate time constraints, or many designers’ abilities to understand them.

An emblematic example of this limited understanding of research methods reduced down to “design thinking” can be found in the popular design publication “Universal Methods of Design: 100 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions” by Bruce Hanington and Martin Bella.[11] Hanington’s and Bella’s cursory, one- to two-page descriptions of 100 design methods are too briefly described to allow many designers to apply them as viable approaches to address complex problems. The authors consider their publication a means to offer designers, especially those new to the processes that guide design decision-making, a valid platform to guide research led by design. Presenting complex methodological approaches in the kinds of brief descriptions on offer here fails to provide enough comprehensive understandings of how and why these approaches should be considered or operationalized. The chapter they include about design ethnography is telling in this regard. The authors acknowledge that design ethnography cannot be compared to traditional ethnography as a method for increasing socio-cultural understanding, since design ethnography is much more limited in terms of the resources and time that most designers have available within a given project’s schedule to engage in it. But Hanington and Bella suggest that designers can “borrow a lesson” from ethnography to build better understandings about various biases that might affect their users or audiences. Design researchers should bear in mind that the results of design ethnography “depend on specific methods used,” and aim at providing designers with “a comprehensive view of their potential users.”[12] Designers who are eager to learn about how and why ethnographic research methods could yield them with empathetically informed understandings of those for whom they are designing apparently do not get much more than this watery result from this cursory description of a methodology that anthropologists spend years learning.

Overall, the lure of design thinking is embedded in promises of allowing designers to engage in a faster, more efficient, and ultimately more successful design process. Professional design consultancies and design educators adopted design thinking because it promised help for designers in three key challenge areas. First, it afforded them a means to produce effective design outcomes informed by less and less easily defined user wants and needs. Second, it allowed them a seemingly efficient way to create work outcomes that might align with or satisfy more convoluted corporate marketing and production strategies. Third, it championed the promise that an ever-broader range of design problems could be successfully addressed against increasingly crushing timelines. In other words, design thinking’s widespread popularity is derived from the promise that it can be deployed as a kind of universal problem solver that empowered overburdened designers to be able to deal with complex problems that may have unforeseen and undesired outcomes, or that cannot be solved at all—the so called “wicked problems.”[f]

The accusations of Justin Maguire and Natasha Jen, combined with other, more academically rooted criticism, reveal that design thinking continues to fail at the task of tackling the kinds of wicked social, technological, economic and political problems that now confront so many of the world’s populations. Unfortunately, design thinking has also succeeded in keeping a good deal of critical assessment and complex problem-framing out of many design decision-making processes. The watered down, contemporary evolution of design thinking has failed to deliver a deeper understanding of how to effectively address wicked problems and the multitude of often intertwined contextual factors—(again) social, technological, economic and political—that constitute them that it purported to originally address. This is especially problematic for individual designers, design consultancies, design researchers and design educators because approaches to design decision-making guided by design thinking continue to leave designers overwhelmed by the complexity and unintelligibility of most of the wicked problems they and their collaborators and clients must now face. Design thinking also now contributes to an increasing void in the critical thinking methods that inform design education at a time when emerging designers can ill afford to be ill-equipped to understand and address these types of complex problems.

These inadequacies call for a more experiential revision of design thinking and the need for the approaches and methods that inform it to become more critically rigorous, broadly informed and capable of facilitating deep inquiry. In light of this, two main research questions guide this paper:

- How can critically rigorous, broadly informed, complex thinking be effectively introduced and implemented within the design thinking process in ways that benefit both design education and practice?

- How can professional designers and design educators then make the best use of this newly configured theoretical approach to engaging in design thinking and effectively incorporate it into their professional practices and curricula?

To address the first question, at least some elements of design practices that incorporate ‘critical design’ must be woven into design thinking. The first step involves analyzing ‘critical design,’ as it described below, and how its theoretical frameworks intersect with design thinking. To address the second question, the results of a workshop[g] conducted with graduate design students will be presented and discussed. This paper finishes with a preliminary and speculative inventory of how to facilitate critical design thinking.

Operationalizing Critical Design as a Cornerstone for Critical Design Thinking

Critical design is admittedly difficult to define and is probably found in some form almost everywhere in the design world. Still, it must be defined to effectively frame the essential argument of this paper. To this end, Matt Malpass, a well-published[13][14][15] expert on the topic and researcher at the University of The Arts in London provides a helpful definition:

Critical design practice is used as a medium to engage user audiences and provoke debate. It does this by encouraging its audiences to think critically about themes engendered in the design work. Operating this way, critical design can be described as an affective, rather than an explanatory, practice in so much as it opens lines of inquiry as opposed to providing answers or solutions to questions or design problems.[16]

Debate is a central tenet of critical design. It revolves around and bolsters the idea that without provocation, there is no broadly informed, deeply plumbed, interrogative dialogue about given decision-making processes, and hence no critical thinking. While this concept establishes a baseline for initiating critical design thinking, it does not also provide the means to facilitate it. To this end, Malpass provides an overly simple answer: by appealing to a given audience’s particular senses and emotions, critical design is said to open up specific “lines of inquiry,” which eventually lead to a more critically and broadly informed understanding of a given problem. By stating that critical design “is not aimed at simplification, but diversification of the ways in which we might understand design problems and ideas,”[18] Malpass underlines the role feelings play in the critical comprehension of the scope of a problem, but also creates a theoretical blank space. If critical design is affective—i.e. it appeals to emotions and not to rationales—how can its criticality work without rational critical analysis? How can critical design transform affect, i.e. the direct, preconscious appeal to a person’s feelings into a distanced and analytical assessment of a given nuisance or problem? In other words, if critical thinking is supposed to be more than an accidental emotional connection based on people’s tastes, fixed opinions or moral convictions, how can critical design achieve this? In Malpass’ concept of critical design, the interdependency of deep reflection and critical thinking remains an aporia. Malpass asserts that the designed object itself contains “epistemic qualities”[18] which in a way “creates a descriptive comprehension of complex issues.”[19] What started as an affective, rather than an explanatory practice, Malpass’ concept eventually turns out to be descriptive in nature. Critical thinking in this notion is predominantly based on the alleged criticality of the object itself. In Malpass’ definition of critical design, critical thinking is the result of broadly informed, intensely reflective inquiry, but the nature and content of these questions remain rather subsidiary in this formal and methodical understanding of criticism. It is a highly debatable assertion that a design object is, in and of itself, provocative in nature and can cause an emotional appeal that then leads to a set of questions that miraculously creates, much less sustains, an enlightened debate. It is even more debatable that this debate takes place among a fragmented audience, and this exchange eventually provokes and facilitates a deep-thinking process and a comprehensive awareness of the complex issues and problems that contextualize the perception and the utility of whatever is being critically discussed. Doubts in this inevitable epistemic chain reaction are backed by the observations that there “is no reliable data that would allow us to make claims about the efficiency of critical design in terms of its potential of influencing a broader audience.”[20]

Malpass unintentionally reveals his theoretical blind spot when he describes design’s ability to spur complex debates when analyzing examples of critical design such as the renowned Hertzian Tales[21] series explored in the book of the same title by the design duo Anthony Dunne und Fiona Raby. Malpass explains that as a work presented in Hertzian Tales, such as the Faraday Chair, “draws attention” to the topic of radiation and electromagnetic fields, it “asks questions” about this topic that “encourages reflection” and ultimately, “exposes part of our material and technological culture that normally goes without consideration.”[22] Interestingly, Malpass never passes the point of praising the work as a means to raise an abstract sense of awareness in his analysis. He simply assumes that a deeper reflection is caused by the questions posed by the design object.

Obscurity or rarity may warrant inquiry, but do not necessarily warrant criticism.[h] Consequently, Malpass praises the work for its “poetic”[24] nature, rather than pointing out a descriptive criticism that the work presents. According to Malpass’ analysis, the ‘epistemic object’ itself provides little deeper understanding of radiation and electromagnetic fields and the political, economic and social contradictions within which they are sustained, but rather a general sense of importance and urgency for its audience.

This is not to suggest that critical design practices could not stimulate debates that might lead to a broader critical knowledge which can then be incorporated into a revised design thinking process. However, to gain critical insights and a deep understanding of complex problems, the focus of this revised design thinking process must surround the debate as it evolves. In Malpass’ conception, critical design is limited due to its concentration on the object rather than the process of inquiry. Visual communication design tends to be most effective when viewed as a means to communicate concepts and ideas which can facilitate debates. ‘Debate’ is defined here as a joint discussion that is controversial and open enough to incorporate conflicting views on a topic. Secondly, it is posited that debate is built on arguments that are not just mere utterances of personal opinions, but reasoned arguments of some sort. Finally, it is posited that debate is centered around the idea of resolving conflicting arguments by weighing them and transforming them into a common understanding. This seems easier on paper than in reality, but a mutual understanding is central to the idea of critical thinking. This is especially relevant for further political actions, such as formulating a collective will and acting on it. As Cameron Tonkinwise, Professor at the University of New South Wales Art and Design in Sydney, Australia, puts it, designers are obliged to “orchestrat[e] the debates through which groups of people come to decide to work together on realizing a particular future.”[25] Creating these debates serves as a cornerstone for critical design thinking. The problems with contemporary design thinking methods are centered around the conviction that meaningful communication design, especially when dealing with the scopes inherent in wicked and complex problems, can only be achieved through joint examination of issues in an open, deep-thinking environment. This is why it is so important to incorporate critical, design-induced debates into design thinking, and to do early in the evolution of a given design process.

Early on in the ideation process, designers as researchers only have a vague and rather general understanding of a given problem—let alone of wicked problems that exceed the usual boundaries of consumers’ interests and preferences. In design thinking, the needs and aspirations of the user serve as the benchmark for innovation and change. But this focus on user needs and aspirations tends to leave out the possibility of using design decision-making to address globally interrelated economic, political, and social problems. Over-focusing on critically considering only the user’s perspective causes a broader understanding of a problem space to get out of sight.

An example of this is the German start-up ‘Share.’ Share provides individual consumers with a good-conscience option by facilitating the purchase of a limited array of consumer goods. As a Share customer, you can buy liquid soap, snack bars or bottles of water and Share takes half of the money earned and spends it on helping to provide aid to developing communities in Africa and southern Asia. Despite the fact that help is given to some of the poorest members of various communities, the practical impact of the funding Share provides to these people is limited by a given consumer’s/user’s interest in helping, which is deeply rooted in an interest to “do the right thing.” From an individual consumer’s/user’s perspective, poverty in Africa and southern Asia is a problem that can be addressed simply by shopping for the right products like the ones provided by Share. This perspective eventually reduces the perception of how poverty affects a large portion of the world’s population to a simple issue that can seemingly be addressed by allowing an organization like Share to provide generous but-relatively-small-scale aid. An alternative to this type of limited, user-centric thinking—what I will deem “the deep-thinking process”—is needed to allow designers to address complex social, economic, public policy and environmental problems in a much broader way. The deep-thinking process connects both the human-centered research aspect of problem identification and framing and the broader understanding necessary to comprehend and address the economic and political dependencies which directly and indirectly affect so many of our discontents. Hence, with regard to the most complex problems that confront contemporary societies, such as achieving and sustaining sustainability, facilitating circular economies, or designing and effectively implementing positive social, economic, and political transformations, deep-thinking guided by broadly informed critical debate is a preferred starting point for design thinking processes.

Although, the status and significance of critical debates about how to engage in the deep-thinking processes necessary to guide critical design thinking may be shared among design educators, the implementation and design of these processes raises key research questions, such as:

- How should a controversial design undertaking that provokes constructive arguments among designers and key stakeholders work?

- How should these arguments be transformed into critically rigorous, scaffolded debate?

- How should this debate be incorporated into broadly informed, deeply probative research processes?

- What should constitute the eventual goal(s) of these types of critical design thinking processes?

For design educators and design practitioners to effectively engage in critical design thinking, it is imperative to answer these questions and then use the knowledge and understandings gained from them to transform them into coherent and applicable decision-making processes that guide design.

Some Theoretical Foundations that Inform Critical Design Thinking

Few texts offer a foundation for addressing, much less guiding, how critical design thinking should be facilitated. Among these texts, the first that will be analyzed here was authored by Liene Jakobsone. It is used to provide an example of an overly general and biased approach, one that suggests merging critical design and design thinking. Jakobsone discusses implementing “the principles of speculative design thinking,”[26] but unfortunately fails to provide a detailed report about what these principles are comprised of or how to apply them to design processes. She concludes by calling for designers to “implement design as a tool to help society escape repressive conditioning.”[27] In Jakobsone’s vision, the already fully politicized and anti-ideological designer uses their tools on a schematic and homogenous society to remove various kinds of repression. This simplistic and general notion of critical design practice leaves central parts of the research questions unaddressed, and, ultimately, unanswered, and therefore does not contribute much understanding or knowledge to help designers and their collaborators effectively engage in critical design thinking.

In contrast, a hypothesis offered by Deger Ozkaramanli and Pieter Desmet is more helpful in terms of how it can help designers and their collaborators address this issue.[28] The authors present a set of guidelines for designing in ways that initiate and sustain provocation and debate. They suggest that designers should attempt to design products and experiences that trigger what they have deemed “personal dilemmas”[29] among project stakeholders and users, and that these should “expose assumptions and stimulate discussion”[30] as a means to encourage deeper levels of self-reflection and awareness about issues of personal (mis-)behavior. Although Ozkaramanli and Desmet rather simplistically assume that, by default, abstract awareness leads to a deeper understanding of complex problems, they provide a step-by-step guide to what they refer to as provocative design. Their theoretical framework for this approach, much like critical design, does not aim to provide simple solutions to complex problems. Instead, the goal is to drive designers and users to experience personal dilemmas through three distinct, carefully crafted and tested design strategies. The first of these makes use of symbols to design objects which “represent conflicting concerns.”[31] Design students, for example, came up with a set of smartphone display symbols that were intended to make users aware of personal behaviors that operated in conflict with each other. One example of this was to use a closed eye to signify a ‘sleeping’ phone—one that could be ignored—and to use an open eye to signify that the same phone was being utilized to facilitate a given activity—or that it needed to be checked. The conflict embedded in this example is supposedly between signifying a given user’s excessive use of his or her phone, via checking it for information, versus his or her ability to leave the phone untouched or ignored.

The second strategy articulated by Ozkaramanli and Deget attempts to trigger personal dilemmas by offering mutually exclusive choices, such as a condom wrapper that opens only on one side, forcing the user to look at a picture of sexually transmitted diseases that not using a condom increases the chances of contracting during sex. The third strategy they articulated challenges designers and users to make certain choices, and to communicate what they believed the “right choice” was, by incorporating subtle but provocative barriers to usage into one or more functional aspects of a given design. An example of this was some of Ozkaramanli and Deget’s design students suggesting a smartphone application that emits annoying noises when people attempt to use their smartphone in social settings where speaking on one could disturb others (i.e., while riding crowded public transport or eating during lunchtime in a busy restaurant). The authors stress that the more the designed objects point to personal dilemmas and the more compelling these are, the more likely users—and those who design for them—will start to reflect on the consequences of their behaviors. The authors also acknowledge the uncertainty of the debate that could surround implementing these approaches to designing and analyzing user behavior by stating that they “may invite interpretation, discussion, and reflection.”[32] For now, it is safe to offer that these strategies, combined with the tactics and methods Malpass developed to guide engagement in critical design, such as post-efficiency, speculation, design fiction, satire, playfulness, discourse, rhetoric, as well as ambiguity, form a reliable base for future debates.[33]

Key Research Findings that form a Basis for Critical Design Thinking

Ozkaramanli and Desmet admit that, when operationalizing these types of provocative design strategies on behalf of specific groups of users, it was particularly difficult for the designers they worked with and surveyed in their workshops to switch from solution-mode to problem-framing mode. Because designers are usually trained to solve problems rather than identify or frame them in ways that make others aware of them (or the contextual factors that have created them to begin with), Ozkaramanli and Desmet’s workshop participants struggled with applying the strategies discussed above.[34]

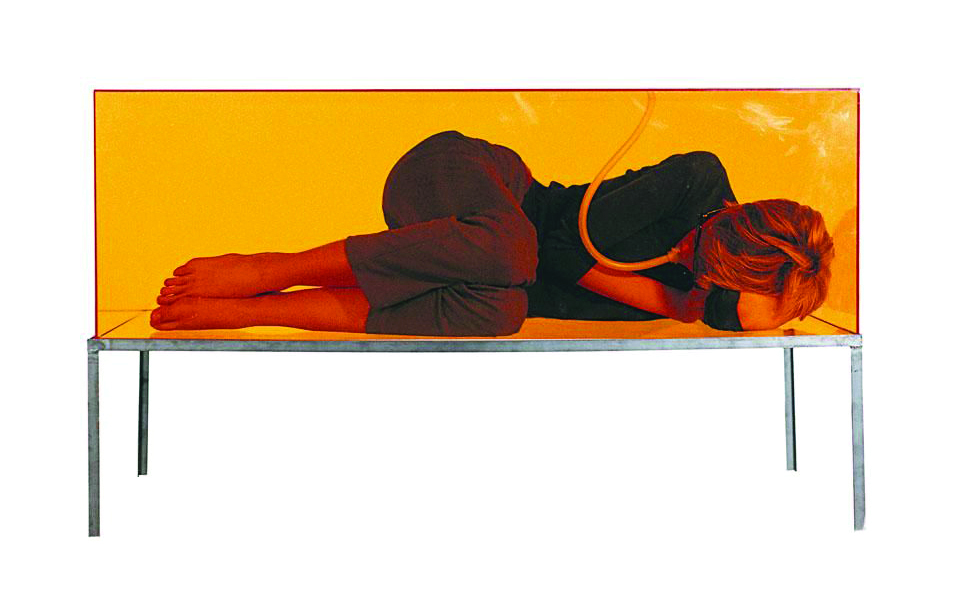

It is crucial to address these issues designers may experience due to occupational expectations as they engage in the decision-making processes that inform their work, and to scrutinize the central pitfalls of a design process that fuels critical debate. As a former post-doctoral research associate at the Hochschule für Medien, Kommunikation und Wirtschaft (HMKW), University of Applied Sciences, in Berlin, Germany, I conducted a one-day workshop with about fifteen master’s-level design students at HMKW’s Department of Graphic Design and Visual Communication to research strategies that inform critical design. All participants were unfamiliar with critical design and the idea of provoking controversial debates by engaging in provocative design processes. The task for the group was to develop a designed object, artifact, or experience that provokes a given audience to question its common conceptions about a given subject matter. The core idea was to create visually communicative design objects, such as posters, animations or small web applications that cause audience members to object to and critically reflect on whatever (preferably controversial) subject matter was being presented. The key challenge was to “hit the controversial subject matter’s sweet spot,” which would allow the audience to engage in the right amount of convincing criticism while still allowing for personal argumentation, and, as necessary, conflict.

It took participants several attempts to get used to the proposed methods and strategies. At first, almost everyone in the group suggested a more or less ready-to-use solution for certain problems. After several rounds of openly discussing these early-in-the-process design results, as well as the process itself, participants actively reflected on the initial goal of the challenge, changed their perspective and then began to engage in the critical design process. This gradual shift in perspective was initiated by both the workshop leaders and the students’ willingness to continue to reflect on whether the initial outcomes of their narrowly and shallowly informed design processes caused the effects that they had initially been challenged to stimulate among their audiences. It turned out that the most promising attempts were guided by three key parameters: first, they touched on a topic that the workshop participants identified as being sensitive, such as personal wealth production; second, they raised concerns around a very concrete point, such as personal income; third, they created enough controversy among the group to cause debate, for example by implying that earning (too much) money is reprehensible.

Personal mindset affected the participants abilities to think beyond the solution-driven perspective that most of them began the project attempting to operate. It also was a challenge for these design students to expel strong personal convictions and beliefs in favor of more balanced, broadly informed, deeply reflective thinking. The goal of engaging in this strategy was twofold: first, it was to encourage participants to refrain from approaching this challenge from too singular a viewpoint; second, it was to ensure that they accounted for the affects and influences of conflicting social, political and economic positions regarding a given topic so as to prevent audiences from assuming too much of a given bias as they experienced a particular designed object. Ozkaramanli and Desmet underline the importance of this twofold strategy when they state:

It might have been helpful to further emphasize the essence of this design intention by, for example, engaging the participants in a debate or a role-playing exercise about the design brief prior to the ideation session. Such exercises might have facilitated the sensitive mind-set of taking different perspectives and stalling moral judgment.[35]

Stalling the rush to moral judgment among some of the student participants became one of the most challenging tasks when conducting this workshop. For example, one participant worked with the strategy of dysfunctional design and created an imaginary digital wallet. The participant designed a mock advertisement poster, which explained the wallet’s function to consumers: the more money the wallet stores digitally, the more it weighs due to the wallet’s materials. As a result, carrying around a relatively small amount, say a thousand dollars, is made impossible, since the wallet now weighs more than two hundred pounds. This example caused a lively debate among the other participants because, on the one hand, they knew that money is the means to satisfy almost all of the material and non-material needs of a given individual, but on the other hand, they rooted for the speculative idea to use the inherent functionality of the “weight-gaining wallet” to restrict access to this means. Participants within the debate were making the point that restricting one’s ability to save money does not mean that income inequalities in the world’s societies will become less flagrant. Some questioned the intention of this wallet, asking what positive effects it may have. Participants also hypothetically tested the functionality of the wallet to determine its relative efficacy. In parallel with observations from Ozkaramanli and Desmet, the design students who participated in this workshop—after some discussion—eventually settled on a specific moral viewpoint. They agreed to understand money as a dysfunctional means to unilaterally facilitate one’s personal wellbeing and interpreted the design of the wallet in light of popular moral principles against gluttonous acquisition of wealth as an unjust chain shackling the humane potential of mankind. Although it was posited that almost everyone needs money and is obliged to earn it, the debate never touched on crucial questions, such as: “What is the essential nature of money if everyone needs it and everything must be paid for with it?” Or, “How is wealth produced?,” and, “Why do so few people have it in abundance while it is so scarce for the majority of the world’s population?” It should be stressed that this kind of moral judgment prevented participants from further investigating into and around the problem space that contextualized this challenge, which led them to agree all-too-quickly on a rather preliminary and self-satisfied point of view.

Concluding this piece begins by addressing the first of its four key research questions, namely “How should a controversial design undertaking that provokes constructive arguments among designers and key stakeholders work?” The results gleaned from the operation and analysis of the workshop suggest that a potentially controversial design object or system that stimulates effectively scaffolded debates needs to be guided by an open, broadly informed array of mindsets among the designers involved. This is not something that happens overnight, but rather evolves as the critical design thinking process is deployed to affect the evolution of continuing projects. Also, designers are humans, and, as such, are deeply embedded in everyday mental and physical routines. For them to cast away ill-conceived thoughts and critically reflect on one or more biased viewpoints they may hold that are deeply rooted in social, economic or political beliefs is time-consuming and requires a great deal of dedicated personal reflection. The revelation of this necessity by far exceeded the narrow temporal and spatial boundaries imposed by the logistical limitations of the workshop. With regard to effectively accounting for, and perhaps even jettisoning, one’s own moralistic judgments to avoid inhibiting critical design thinking, I would suggest asking the following: do one’s personal convictions regarding a particular subject matter allow for them to be contested by a well-made, pointed argument? If not, maybe long-cherished convictions in the form of what one had considered to be indisputable higher social, economic or political principles may be worth questioning or even abandoning.

Designers should also strive to create objects, systems and experiences that evoke an open, investigative user’s mindset. To do so, they should attempt to frame the problems they wish to confront in contradictory ways, rather than offer solutions informed by single or myopically framed viewpoints or that suggest there is but one way to interpret and to attempt to resolve the problem. Because outcomes of design processes informed by critical design thinking are by nature contradictory and provocative, these should be self-explanatory. This assures that they appeal to the senses, create questions and therefore prepare and fuel effective, broadly informed debates.

Some Fundamental Speculation about the Critical Design Thinking Process

It is particularly tricky to effectively address the second key research question, “How should these arguments be transformed into critically rigorous, scaffolded debate?” As explicated in the paragraphs above, this question touches on the limitations of a given designer’s experiences as a practitioner and on his or her accrued expertise. For a debate that informs a design process to be fruitful, it must not only be judiciously stimulated, but it must also be thoughtfully guided and managed, both in terms of content and etiquette. This requires certain types of skill, knowledge and experience as a moderator, and, as necessary, as a mediator. Additionally, no designer can possibly cover all these fields of expertise and be well-versed in the myriad of social, political, and economic topics he or she may have to address during a given critical dialogue. Therefore, it becomes useful to open up the facilitation process to professionals, experts, advocates, and external facilitators, such as activists for a specific subject matter who have experiential knowledge of and about how to effectively facilitate and moderate debate. I did not have the opportunity to test this during the workshop I facilitated that forms the basis of this analysis due to time and budget constraints, hence what I am suggesting here is speculative in nature. However, it is important to discuss the facilitation of this process.

The practice of engaging in critical debate itself, much like the practice of engaging in complex innovation processes such as design sprinting,[36] (a process that was designed by Jake Knapp to address pressing design problems quickly), must be a team effort informed by a diverse group of people. Design sprints usually involve people who possess different skill sets and bases of knowledge that can contribute to the articulation and understanding of a variety of viewpoints to provide helpful insights about how to effectively frame and confront certain problems. Within the context of critical design thinking, the designer should be part of these practices, but he or she should not necessarily be the focal point or driving force. The group ideally consists of a handful of experts and thinkers from a range of different fields and disciplines, as well as one or two designers and equally as many users or “everyday experts” (i.e. people who have gained familiarity with a given problematic situation due to their daily immersion in it). There are many viable ways to recruit these people, such as by collaborating with NGOs that could contribute subject matter experts, or by involving market research firms that pay users to participate in given types of analysis and assessment processes. If the topic and goal of the project is something on behalf of which a specific group of people would want to dedicate their time and effort, users from this group can often be inexpensively recruited via social media platforms. Team members could also be selected from design organizations that typically formulate and operate critical design projects, who often benefit from having employees from diverse disciplinary backgrounds working for them. In this way, criticality is not skewed toward the biases of one or more critical stances that have been adopted by the designer involved in the endeavor, but can instead be systematically introduced into the design thinking process.

For the members of the team, their intentions and motivations to participate may differ. Design activists may want to solve issues that they have identified as being close-at-hand, while potential or extant users may want to convey their discontent with particular aspects of an object’s, system’s or experience’s operation or perception in the hope of improving at least some aspects of these, and while subject matter experts may want to share (or impose) their knowledge, and while moderators may simply want to dedicate their skills to facilitating a critical discussion on behalf of advancing a good cause. It is important to communicate the critical design thinking process, as well as its possible outcomes and gains, in advance to motivate team members, but also to prevent frustration deriving from false expectations. It should be conveyed to all team members that the research process does not resemble a typical design thinking process, but is instead initiated by engaging in a controversial dispute. It should also be conveyed that developing a given designed object, system or experience is not necessarily the overall goal of the process, but serves merely as an entry point, or “kick-off,” for critical discussions.

The critical design thinking process consists of two main phases. The first fosters open and divergent thinking and the second is determined by convergent thinking and the search for some sort of ‘solution.’ Before the debate can start, designers (of course) must develop a viable design prototype, one that “is capable of stirring up debate.” They should consult with the team’s experts to discuss possible hidden aspects of the topic at hand and test-run their ideas. Once the debate progresses, ideas and convictions offered during the discussion should be jotted down and visualized so that all involved may quickly access its contents, and so that they may be clustered according to their social, economic and political implications. The facilitator should be able to point out contradictions and encourage members of the team to argue for or against a conflicting point of view as a means to possibly dissolve the conflicting views, or at least achieve compromise regarding them. The facilitator should also monitor the team member’s verbal and non-verbal behavior in order to prevent single individuals to dominate the discussion. In the event of single-sided communication the facilitator could actively address this imbalance or give the floor to someone less vocal. The facilitator should also prevent moralistic discussions by addressing long-cherished conviction that are willfully withdrawn from critical debate. Facilitators also should point out when discussants render discussion irrelevant by bringing in ideals and proposing simple solutions.

The result of the divergent thinking phase should be not only a clearer understanding of the criticism raised in the debate, but also of the underlying reasons for discontents and grievances. The idea of the debate is to gain both, insights into people’s personal convictions and into overall economic, political, and social interrelations. These insights can then—in the second phase—be transformed into preliminary ‘solutions’, such as meta-comments and design guidelines.

To integrate the debate’s results into a broader research process, design thinking must be partially suspended as a way to create successful products for customers’ needs. Design thinking’s pain points and aspirations of users are not simply transformed by this new process into actionable insights that ultimately produce a product that satisfies these needs. The objective of a critical design thinking is to reveal people’s critical thoughts and incorporate them into the ideation process. The critical debates involved in this process reveal people’s values and personal worldviews, which might be used to more effectively design a mass market product.[i] Critical design thinking’s outcome rather aims at taking a group’s critical understanding and addressing problems that are not simply solved by a new product. Instead it seeks to implement an innovation process that reflects on the insights gained and on design’s role in problematic political, economic and social realities.

The insights derived from critical discussions can then be transformed into guidelines, manifests, handbooks, or meta design tools that subsequently inform and guide a broader range of critical design decision-making processes. This is a much more ambitious goal than attempting to design or re-design a single product. For example, a guide that describes circular design processes can inform designers about why circular design solutions are sometimes desirable and beneficial. This guide may state that circular design requires a carefully considered use of materials—in terms of how this use affects the relative availability and sustenance of a variety of resources—and hence suggest that massive research efforts be undertaken in the near future to either alter the development of these materials or invent or incorporate substitutes. It could also provide designers and activists with a set of strategic partners and a critical innovation framework that most likely yield well-thought-out results.[j] A manifesto, on the other hand may criticize the use of non-toxic and non-wasteful materials in relation to corporate agendas. The manifest may transform the debate into radical criticism and state that traditional design as well as circular design necessarily fall short within a system that values corporate growth more than healthy living conditions. The manifesto could then call for a different kind of economic order with a different purpose for design.

Conclusion

The lack of criticism currently undermining the ability of designers and their collaborators to utilize design thinking to affect design methodology serves as an entry point to guide strategic discussions. These can and should introduce critical thinking into the practice of design thinking as a means to improve its efficacy as a means to guide design decision-making. Critical debates are a central tenet of critical design, but are often underexposed as such, since critical design thinking is based on the effective facilitation and moderation of critical debates. The importance of facilitating and moderating these, as well as suggesting ways to initiate them outline means for designers and their collaborators to effectively utilize this method. Foremost, these debates need to be fueled by the analysis of socially, economically and politically controversial design objects, systems and experiences that instigate, or “trigger” personal dilemmas. They can also be fueled by post-efficiency or ex-post (i.e. “after the fact”) assessments of extant design objects, systems and experiences, as well as speculation, satire, use of rhetoric or purposeful ambiguity, and a general refrain from perpetuating moralistic convictions and stereotypical thinking. By creating an investigative curiosity, provocative designs aim at facilitating a critical debate that is supported by a team of experts, users, and designers. Led by facilitators, these debates ideally fuel changes of perspectives about the factors and conditions that contextualize a given design problem, and reveal multiplicities of means to address and analyze it. This deep-thinking experience then informs future design processes by taking whatever knowledge and understandings have been acquired and transforming them into critical annotations, guidelines, manifests, lexica, or other forms of meta design tools. By suggesting ways to productively merge practices of critical design with design thinking into a more critical design practice, as well as a more critical educational practice, critical design thinking can be utilized to ensure that design solutions adequately address and resolve the depth and complexity of 21st century problems. Knowing that transformations in society are not always subject to how decision-making can be affected by design thinking, critical design thinking requires further explorations and applications to adequately test the capability of this speculative approach.

References

- Almquist, E., Senior, J. and Bloch, N. “The Elements of Value. Measuring –and Delivering–What Consumers Really Want,” Harvard Businesses Review 94.9 (September 2016): pgs. 47–53.

- Brown, T. Change By Design. New York, NY, USA: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009.

- Buchanan R. “Wicked Problems In Design Thinking,” Design Issues 8. 2 (1992): pgs. 5–21.

- Cross, N. “A History Of Design Methodology,” in Design Methodology and Relationships with Science, ed. by M. J. de Vries and D. P. Grant. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1993, pgs. 15–27.

- Cross, N. Design Thinking. Understanding How Designers Think and Work. Oxford, UK: Berg, 2011.

- Dunne, A. Hertzian Tales: Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience, and Critical Design. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2006.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation, “What Is The Circular Economy,” Online. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/what-is-the-circular-economy (Accessed May 15, 2019).

- Fortune Magazine, “Brainstorm Design 2018,” March 14, 2018. Online. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TWwTN1pS2eg (Accessed June 28, 2018).

- Hanington, B. and Martin, B. Universal Methods of Design: 100 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions. Beverly, MA, USA: Rockport Publishers, 2012.

- Jakobsone, L. “Critical Design As Approach To Next Thinking,” The Design Journal 20.supl. (2017): pgs. S4253–S4262.

- Jen, N. “Design Thinking Is Bullsh*t,” June, 2017. Online. Available at: https://99u.adobe.com/videos/55967/natasha-jen-design-thinking-is-bullshit (Accessed June 28, 2018).

- Jonas, W. “A Sense of Vertigo. Design Thinking As General Problem Solver,” Institute For Transportation Design, July, 2010. Online. Available at: http://8149.website.snafu.de/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/EAD09.Jonas_.pdf (Accessed September 20, 2018).

- Kimbell, L. “Rethinking Design Thinking: Part 1,” Design & Culture 3.3 (2011): pgs. 285–306.

- Knapp, J. Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days. New York, NY, USA: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

- Malpass, M. “Between Wit and Reasoning: Defining Associative, Speculative, and Critical Design in Practice,” Design & Culture 5. 3 (2013): pgs. 333–356.

- Malpass, M. “Criticism and Function In Critical Design Practice,” Design Issues 31. 2 (2015): pgs. 59–71.

- Malpass M. Critical Design In Context. History, Theory, and Practice. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- Ozkaramanli, D. and Desmet, P. “Provocative Design For Unprovocative Designers: Strategies For Triggering Personal Dilemmas,” in Proceedings of DRS: Design + Research + Society – Future-Focused Thinking, Volume 5, ed. by P. Lloyd and E. Bohemia. London: Design Research Society, 2016, pgs. 2001–2016.

- Papanek, V. Design for the Real World. Human Ecology and Social Change. New York, NY, USA: Pantheon Books, 1979.

- Rittel, H. and Webber, M. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” Policy Sciences 4.2 (1973): pgs. 155-169.

- Rodgers, P. “Paradoxes in Design Thinking,” The Design Journal 20.sup1 (2017): pgs. S4444–S4458.

- Stickdorn, M. and Schneider, J. This Is Service Design Thinking. Amsterdam, Netherlands: BIS Publishers, 2016.

- Tonkinwise, C., “Responses for 21st Century Design After Design xxi Triennale di Milano,” no date. Online. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/25208645/Cameron_Tonkinwise_Responses_for_21st_Century_Design_After_Design_xxi_Triennale_di_Milano (Accessed July 12, 2018).

Biography

Sebastian Loewe is currently a Professor in Design Management at the Media-design Design School in Berlin, Germany. Prior to this appointment, Professor Loewe worked as a post-doctoral research associate at the Department of Graphic Design and Visual Communication at the HMKW University of Applied Sciences in Berlin, Germany, where he engaged in research on critical design thinking. The subject of his PhD dissertation is the discoursive nature of kitsch; it was published in 2017 by Neofelis Press, Berlin as “Als Kitsch ausgewiesen!: Neuaushandlungen kultureller Identitaet in Populaer-und Alltagskultur, Architektur, Bildender Kunst und Literatur nach 1989” (“Proclaimed as kitsch!: renegotiations of cultural identity in popular and everyday culture, architecture, fine arts and literature after 1989).” Professor Loewe holds a Bachelor’s degree in media and communication studies along with a diploma in media arts. He co-founded the socially-engaged art and design platform ufo-University. ([email protected])

Notes

- a

Circular Design is a term referring to design practices in accordance to principles of a circular economy, as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation points out. (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, “What Is The Circular Economy,” 15 May, 2019. Online. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/what-is-the-circular-economy (Accessed May 26, 2019).

- b

Social design is an umbrella term for design practices that aim at tackling socio-political issues in order to bring about social change. Victor Papanek is often referred to as an intellectual pioneer of social design. (Papanek, V.: Design for the Real World. Human Ecology and Social Change. New York, NY, USA: Pantheon Books, 1979.) The Social Design Futures Report gives a well-based introduction to contemporary social design practices in the UK. (Armstrong, L., Bailey, J., Julier, G. and Kimbell, L. Social Design Futures. HEI Research and the AHRC. Brighton, UK: University of Brighton, 2014. Available at: https://mappingsocialdesign.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/social-design-report.pdf; accessed May 26, 2019.)

- c

The next paragraph takes a deeper look into current criticisms on design thinking.

- d

Design thinking is defined as a lean management tool that consists of a variety of sub-tools with emphasis on iteratively and heuristically guided user-research that informs quick prototyping. Central to the development of design thinking as a broadly accepted design management tool are the efforts of the Hasso Plattner Institute (HPI) at Stanford, ca, usa and Potsdam, Germany to publicize it as such, as well as the efforts of the California-based design firm ideo. Both organizations promote design thinking as a kind of toolkit that facilitates universal problem-solving that doesn’t necessarily require specific, traditional, formal design skills. ideo’s co-founder Tim Brown proclaims that design thinking can be applied by almost everyone to solve nearly every problem they might have to confront without having to plumb knowledge cultivated from a deeper understanding of design practices. (Excerpted from Brown, T. Change By Design. New York, NY, USA: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009).

- e

Tomás Maldanado and Horst Rittel began to introduce some of the ideas that came to be known as “design methods” at the Ulm School of Design (Hochshule für Gestaltung Ulm) in the late 1950s, and J. Chris Jones and L. Bruce Archer began to do this just a few years later in the U.K.

- f

The term ‘wicked problems’ was coined by design theorists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber. See: Rittel, H. and Webber, M. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” Policy Sciences 4.2 (1973): p. 155.

- g

The one-day workshop addressing critical design was conducted during the fall semester in 2017 within the context of the seminar “Design Leadership” at the Hochschule für Medien, Kommunikation und Wirtschaft (HMKW), Berlin, Germany. Fifteen participants—all master-level design students—where introduced to the methods of critical design and instructed to implement these methods within a group project.

- h

Take scientific principles for example. Just because these principles, such as gravitation, magnetism, or quantum mechanics, are not tangible and as abstract laws remain hidden from the viewer, does not mean they can or must be criticized.

- i

This is where value marketing comes in. Value marketing builds on personal values, such as a sustainable life or personal wellbeing and fitness. If people’s lives essentially revolve around specific values, corporate marketing uses these values to design products that cater to a person’s set of values. See: Almquist, E., Senior, J. and Bloch, N. “The Elements of Value. Measuring–and Delivering– What Consumers Really Want,” Harvard Businesses Review 94.9 (September 2016): p. 47.

- j

The design firm IDEO came up with a Circular Design Guide, but they themselves admit that the guide is “biased towards action”. Online. Available at: https://www.circulardesignguide.com (Accessed 20 September, 2018).

Buchanan R. “Wicked Problems In Design Thinking,” Design Issues 8. 2 (1992): p. 5.

Stickdorn, M. and Schneider, J. This Is Service Design Thinking. Amsterdam, Netherlands: BIS Publishers, 2016.

Lewrick, M. The Design Thinking Playbook: Mindful Digital Transformation of Teams, Products, Services, Businesses and Ecosystems. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 2018.

Cross, N. Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work. Oxford, UK: Berg, 2011.

Jonas, W. “A Sense Of Vertigo: Design Thinking As General Problem Solver,” Institute For Transportation Design, July, 2010. Online. Available at: http://8149.website.snafu.de/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/EAD09.Jonas_.pdf (Accessed September 20, 2018).

Rodgers, P. “Paradoxes in Design Thinking,” The Design Journal 20.sup1 (2017): p. S4444.

Kimbell, L. “Rethinking Design Thinking: Part 1,” Design & Culture 3.3 (2011): p. 285.

Jen, N. “Design Thinking Is Bullsh*t,” June, 2017. Online. Available at: https://99u.adobe.com/videos/55967/natasha-jen-design-thinking-is-bullshit (Accessed June 28, 2018).

Fortune Magazine, “Brainstorm Design 2018,” March 14, 2018. Online. Available at: hhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TWwTN1pS2eg (Accessed June 28, 2018).

Cross, N. “A History of Design Methodology,” in Design Methodology and Relationships with Science, ed. by M. J. de Vries and D. P. Grant. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1993, p. 16.

Hanington, B. and Martin, B. Universal Methods of Design: 100 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions. Beverly, MA, USA: Rockport Publishers, 2012.

Malpass M. Critical Design In Context: History, Theory, and Practice. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Malpass, M. “Criticism and Function In Critical Design Practice,” Design Issues 31. 2 (2015): p. 59.

Malpass, M. “Between Wit and Reasoning: Defining Associative, Speculative, and Critical Design in Practice,” Design & Culture 5. 3 (2013): p. 333.

Malpass, M. Critical Design In Context: History, Theory, and Practice. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Malpass, Critical Design, pgs. 41–42.

Jakobsone, L. “Critical Design As Approach To Next Thinking,” The Design Journal 20.supl. (2017): p. S4253.

Dunne, A. Hertzian Tales: Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience, and Critical Design. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2006.

Dunne, A. Hertzian Tales: Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience, and Critical Design. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2006, pgs. 13–17.

Tonkinwise, C., “Responses for 21st Century. Design After Design XXI Triennale di Milano,” no date. Online. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/25208645/Cameron_Tonkinwise_Responses_for_21st_Century._Design_After_Design_XXI_Triennale_di_Milano (Accessed July 12, 2018).

Ozkaramanli, D. and Desmet, P. “Provocative Design For Unprovocative Designers: Strategies For Triggering Personal Dilemmas,” in Proceedings of DRS: Design + Research + Society – Future-Focused Thinking, Volume 5, ed. by P. Lloyd and E. Bohemia. London, UK: Design Research Society, 2016, p. 2001.

Knapp, J. Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.