A Blended Perspective: Social Impact Assessment in Graphic Design

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Many graphic designers, also known as visual communication designers, user-experience designers, and/or interaction designers, advocate for social design agendas in their practices. These designers are concerned with addressing and attempting to resolve complex problems within and around the social, technological, economic, environmental and/or political landscapes of our societies. In so doing, they are often faced with the challenging task of assessing the impacts of these practices in order to understand and measure affected change accurately and ethically, often aiming to weigh and respond to the needs of many stakeholder groups. In order to do this effectively, designers should have a deeper understanding of evidence-based research methodologies that allow them to monitor the social consequences, both positive and negative, of the design systems that they create. This paper reviews social impact assessment from two perspectives—design and the social sciences—and proposes that key approaches and methodologies derived from the social sciences be integrated into the design process to improve and more broadly inform the decision-making of designers and their collaborators.

In the context of this piece, social impact assessment, or “SIA,” is a process that can be used to identify and manage the social impacts of a wide variety of public and private policies, plans, and programs, as well as industrial projects and large- and small-scale community initiatives.[1] When used effectively, social impact assessment invites the participation of affected communities and stakeholders in key decision-making processes, from the outset of a project through to its conclusion. Well-planned, managed and operated social impact assessment helps 1) to ensure that potential negative effects stemming from the realization of a given project are anticipated and mitigated, and 2) to ensure that local communities and stakeholders derive the greatest benefits from the realization of the project.

By applying a more rigorous social impact assessment as a critical review of the design process, designers may be able to confront and more effectively influence the short-, medium-, and long-term implications of the work they are producing, understanding with greater conviction how almost any given array of work will impact potential social groups, economic and manufacturing sectors, political agendas, and other contexts. The result of the SIA reviews is a blended perspective that includes defined phases with descriptions and action items that may be used by researchers, educators, practitioners, and students to effectively assess social impact in the design discipline as a major outcome of the work.

Introduction

Today’s graphic designer has a lot to consider regarding the scope of issues and concerns that affect, or could affect the operation of his or her practice. Compared to the modernist values of the industrial-era designer, who was primarily concerned with improving the function and appearance of messages, products, services, and environments, today’s post-industrial, information age designer is juggling a much greater complexity of variables. Working within the challenges of the information age, the graphic designer must now address, or at least consider, the densities of large-scale, systemic design problems that require interdisciplinary and collaborative methods to effectively facilitate problem-framing and problem-solving. These endeavors often require multidimensional processes that evolve into cross-platform solutions (most often combinations of digital and physical communication systems) that attempt to enhance the experiences of many by considering the sustainability and equitability of the design’s implications on the world at large. These variables hinge upon one another, relying on the effective application of participation and engagement to inform and guide the practice. Rather than thinking about design processes that improve the formal and functional attributes of single artifacts, typically designed, executed and distributed on behalf of particular audiences or groups of users, today’s graphic designer is more likely to be engaged with many diverse stakeholder groups, employing a human-centered design process to create multifaceted communication systems, realized with and by many different types of people. This new type of graphic designer can be identified as a visual communication designer, a user-experience designer, an interaction designer, and several other monikers (some of which describe overlapping skill sets and bases of knowledge).[a] He or she now works within many interconnected and diverse contexts as his or her practice has evolved well beyond object-based, single artifact design to include systems, networks and communities of services, policies, experiences, interactions, and engagements.

Intertwined with this complexity, graphic designers are also faced with the difficult task of prioritizing the critical social, technological, economic, environmental, and/or political issues that encompass the ever-broadening discipline of graphic design. According to the 2017 Design Census (https://designcensus.org/),[b] “consumer vs. social impact focus” was one of the top ten most critical issues and challenges currently facing all of the design disciplines. Where the industrial-era designer might have focused primarily on a specific consumer or end-user when addressing and resolving given design problems, today’s designer must account for and leverage the needs and opinions of many stakeholder groups. The AIGA Designer 2025 report, released by the AIGA Design Educators Community around the same time, defined “accountability for predicting outcomes for design action” as a major competency for the future of the evolving discipline. The report states that designers are expected to produce “evidence-based design research” to inform decision-making when addressing and attempting to resolve design problems, and to “conform to rigorous standards and be measured by the same metrics,” suggesting that the design discipline and profession “adapt methods borrowed from other disciplines.”[2] AIGA Eye on Design synopsizes the report, affirming that designers must “negotiate the concerns of various stakeholders within projects and also evaluate their work in terms of its potential social, cultural, technological, economic and environmental impact.”[3] As evidenced in this report, assuming accountability for design interventions are a current and future condition of the discipline and profession, which demands confronting the short-, medium-, and long-term implications that producing a given array of work will have on social groups, economic and manufacturing sectors, political agendas, and other contexts. The report not only articulates a need for designers to be accountable for the work they produce and disseminate, but it also states the demand for more efficacious measurement methods for evaluating how the outcomes of specific design processes affect how people live and work on a daily basis within particular societies.

If social impact is one of the key focus areas and critical issues currently facing design, and the accountability of design interventions and actions are a condition of the present and future of the discipline, then it is imperative that graphic designers understand what social design is, how it should or should not be considered within the design discipline, and how to address and assess social impact in such a way that tangible change, achieved and affected through the operation of design processes, is evaluated with the same critical rigor and expectations inherent in other disciplines.

Investigating the Social Agenda in Graphic Design

Social design, also referred to as socially conscious design, social impact design, or socially responsible design,[c] refers to “the practice of design for the public good, especially in disadvantaged communities.”[4] It is a widely recognized critical area of study and is often considered by many designers as either a unique specialization or as part of a broader design practice that encompasses basic social design principles and practices. It is often described as a transdisciplinary approach to design—relying on various expertise being asserted across disciplines such as architecture, anthropology, sociology, economics and public policy to fully understand and apply the scope of knowledge required to work within the field. This is because social design is often practiced in and around more complex contexts that involve accounting for the effects of intertwined narratives and concerns. In the white paper based on the Social Impact Design Summit in New York (February 27, 2012), Laura Kurgan, Associate Professor of Architecture at Columbia University, states: “Being socially responsible—or solving urban problems through design—means addressing politics, globalization, health, education, criminal justice, or economics, among others.”[5] Graphic designers that wish to practice social design must rely heavily on neighboring disciplines to expand their knowledge and expertise. Most often, this is accomplished through collaboration with experts from disciplines outside design and interaction with diverse social groups. These designers depend on a collaborative creative process to attempt to address and effectively resolve complex social issues in communities by understanding the needs of various stakeholders to maximize design’s positive impact on a given society and minimize the negative.

In the graphic design literature, there is no shortage of social design advocacy among scholars and educators within the discipline. Most agree that design should play a significant role in addressing societal issues either within or in addition to their design practice. Victor Papanek, a pioneer among advocates of social design agendas, promoted responsible design practices in his book, Design for the Real World (1971, 1984). He stated that the designer’s “social and moral judgement must be brought into play long before he begins to design, since he has to make a judgement, an a priori judgment at that, as to whether the products he is asked to design or redesign merit his attention at all.”[6] Papanek identifies the designer as both a planner and strategist, asking him or her to question the purpose of design actions before production and implementation, and to consider the impacts that it will have on society. Steven Heller and Veronique Vienne in Citizen Designer: Perspectives on Design Responsibility (2003) and Elizabeth Resnick in Developing Citizen Designers (2016), among others, write about the value and significance of design responsibility and good citizenship within the design discipline. Heller argues that, “a designer must be professionally, culturally, and socially responsible for the impact his or her design has on the citizenry.”[7] Resnick claims that “designers have both a social and moral responsibility to use their visual language training to address societal issues,”[8] and encourages designers “to adopt a proactive role to effect tangible change to make life better for others.”[9] As early as the 1960s, designers attested to the betterment of society in the First Things First Manifesto (1964), published by Ken Garland, which proposed “a reversal of priorities in favor of the more useful and more lasting forms of communication.”[10] To surmise, the underlying message is consistent across the literature—that designers should use their knowledge and skills to be proactive citizens, to design socially, morally, and ethically responsible artifacts and design systems, and, if possible, to affect change in the world through design practices that yield positive social, technological, economic, political and/or environmental impacts within broader societal contexts. Design, whether it be the design of messages, products, services, systems, experiences, or interactions, should be implemented ‘for good.’[d]

This is encouraging for the graphic design discipline, as it indicates that designers can and should address and integrate social design practices within the discipline and profession. Particularly emphasized in education, students are more likely exposed to opportunities and possibilities for using their design knowledge and skills to support ‘design for good,’ often under the direction and guidance of a professor or mentor. In these cases, many promote and encourage social agendas in their design teaching and processes and in so doing, at least partially, recognize and attempt to identify and frame social design objectives and methods into practice. What is unclear, or at least challenging to decipher, is to what extent and for what purposes are designers actually integrating (and teaching) social design practices, and not simply advocating for social agendas that they themselves deem ‘good.’ If social design practices require us to address complex contexts and narratives that weigh the values and concerns of many stakeholder groups, often contradictory in need and priority, then how are designers gauging what is ‘good’ in order to maximize design’s positive impact on society—or on a particular group or groups within it—and minimize the negative? Because ‘good’ is subjective, attempting to agree on what is ‘good’ is not really plausible, as one person’s positive is another person’s negative, depending on each person’s life experiences and personal circumstances. Social design practice can eliminate, or at least minimize, this subjective and possibly biased declaration of what is ‘good’ by incorporating scientific measures for identifying and evaluating social impact.

Doing this effectively means that designers should, from the beginning of a given project, attempt to recognize and resolve to what extent, and to what level and capacity, they wish to adopt social design principles and practices into their design processes, and to be clear about any indicated social, cultural, economic, political or other societal intentions and implications they hope to address. For example, some designers may not need or want to adopt social design processes that weigh the impacts of their decision-making on specific societies into their practice, and instead simply advocate for social agendas by aligning their practice with values that are important to them. These designers may consider the broader consequences of their work, design responsibly based on their beliefs, and recognize probable benefits associated with societal growth, but will not gauge or quantify the impacts of the outcomes of their processes based on metrics that verify affected change within or around broader contexts and stakeholder groups. For many, this satisfies one’s need to integrate social agendas into their practice. The social implications of the work are inherently positive, and the affected change is implied, however, these designers should articulate a clear distinction within their practice and recognize the difference between promoting social agendas in one’s work versus actually affecting positive change through social impact initiatives and measuring their implications.

The designer who wants to take their social practice beyond the ‘promotion of a social agenda’ level and capacity must engage in two crucial, sequential steps. First, he or she must identify and then negotiate the concerns of various stakeholders at the outset of his or her design process. Second, he or she must then plan and operate it in a way or ways that help to improve local, regional, and global issues related to public health, poverty, economic and community development, and so on. This is a complex undertaking that requires a scientific evaluation of the impact of the outcome(s) of a given design process with a more in-depth social impact analysis than most designers have been educated or trained to undertake. This demands more than good intentions and theoretical assumptions, but rather a deeper understanding of social design tools and methods for using them in ways that can aid the designer’s investigation of the short-, medium-, and long-term implications that producing and implementing a given array of work will have on the range of stakeholder groups affected by the realization of a given project. Therefore, designers should identify, frame, and strategize social design endeavors with social impact goals in mind, and they should articulate these before initiating an implementation process. For example, one design project goal might be to create food packaging that enables a local community garden to sell their produce at the local weekly farmer’s market, whereas another—broader—goal related to this design project might reach beyond this, and involve attempts to design food packaging that enables a local community garden to decrease waste, increase sales beyond their local weekly farmer’s market, or improve the economic state of an underserved community. The first goal may not require an in-depth social impact analysis, while the second might (and probably should). In order to understand change in this context, designers need to integrate more rigorous systems for measuring and monitoring the effects of the implementation and dissemination of the work they produce. In this case, it is worth noting that many designers may never be able to do this without more sophisticated and accessible information, methods, and tools necessary to allow them to engage in evidence-based analysis. The designer interested in expanding the role of design to include more in-depth, evidence-based research methods and analysis techniques needs to consider social impact assessment with viewpoints derived from looking through multiple lenses—not just through those informed by design, but by across the spectrum of the social sciences as well.

Examining Social Impact Assessment through the Design Lens

In contemporary design, the importance of effectively measuring and assessing the social impact of design interventions and actions, and then effectively reporting on these findings, has become apparent in a time of ever-increasing disparities in wealth distribution around the world, dwindling natural resources, and the rise of more nationalistically slanted, exclusive-rather-than-inclusive governments and government programs. Many design educators and researchers in developed and developing countries agree that social impact assessment should be integrated into the design process, and that it should also perform a critical function and responsibility that affects how designers discuss, frame, conclude, and disseminate their work. In response, many designers are actively investigating efforts to improve the social impact assessment knowledge and methods being deployed across both its academic and professional spectrums. From an array of published toolkits such as IDEO’s Design Kit: The Human-Centered Design Toolkit (https://www.ideo.com/post/design-kit), and FROG’s Collective Action Toolkit (https://www.frogdesign.com/work/frog-collective-action-toolkit) to online case studies and resources at sites such as the AIGA’s Design for Good Initiative (www.aiga.org/design-for-good), many designers are working to develop and share social impact assessment resources within the design community. These resources help contextualize what social design is, and how graphic designers can more effectively engage in socially responsible design practices. More specifically, they help guide designers’ decision-making when it comes to determining what types of projects to engage in, who to work with to realize them to good effect, and, to some extent, how to accomplish them in ways that actually improve a particular social, technological, economic, environmental or political situation on behalf of a specific group.

These resources also provide some insights to designers who wish to develop and implement more socially responsible design processes, which provides a good introduction for designers who wish to better understand the overarching principles that guide some aspects of socially responsible design practices. Unfortunately, there are shortfalls inherent in the utilization of resources like these, particularly with regard to their inability to guide the kinds of broadly framed, deeply plumbed critical inquiry necessary to measure and monitor social impact that meet the rigorous, interrogatory standards of other disciplines. These shortfalls are evident in both the tools available to designers to facilitate would-be social impact assessments of given project outcomes, as well as the reports and findings published from case studies. Most of the toolkits described above offer vague, high-level instruction, while the case reports publish little to no supporting evidence of affected change based on viable, credible impact assessments of specific, socially rooted objectives and outcomes. Much of the published material that has documented the results of socially impactful (or potentially socially impactful) design initiatives and projects tends to be documented and disseminated in ways that couch descriptions of outcomes within theoretical implications that only loosely support given social agendas. This is quite different, and subject to much less methodological and documentary rigor, than relying on a scientific method of evaluation that requires evidence-based research to support claims of tangible change in broadly or narrowly defined societal contexts.

What much of the scholarly literature written from the design perspective does articulate is that assessing claims of tangible, societal change must be measured through a comparative metric, which is then noted in both the scholarly literature of design and the social sciences. Andrew Shea, a communication designer working within the realm of social design practice, states that designers should “craft methodologies that help them record conditions at the start of the project and then how those conditions changed because of their design solution.”[11] This statement is generally based on the theory of change, which is a particular type of methodology for planning and evaluating social change. It examines short-, medium-, and long-term societal objectives, and maps them backwards to examine cause (pre-conditions) and effect (post-conditions). It is focused in particular on mapping out or “filling in” what has been described as the “missing middle” between what a program or change initiative accomplishes (its activities or interventions) and how these lead to desired goals being achieved.[12]

Shea’s statement articulates, on a very high-level, how the theory of change is demonstrated and how designers may employ it to glean insights about how to effectively measure social impact. If one can measure cause and effect, in a controlled environment, one can evaluate the changes based on a clear objective over a set span of time. What is missing from this statement are the details that depict and describe at least some of the evidence-based research methods and analysis techniques required to measure and monitor cause and effect. Without such details, designers may not be able to discern the precise methods necessary for assessing social impact accurately in their design processes.

The AIGA Design for Good website (largely based on the work of Mark Randall) outlines steps for initiating and implementing a social design project, one of which identifies ‘measure’ as an actionable item for impact assessment. The item description for measure reads: “think about data and metrics early on, evaluate your work, and constantly ask yourself if you’ve achieved your goals.”[13] This language describes a guiding principle rather than a procedural step; it suggests some sense of how to loosely measure impact, but the gaps in the description Randall offers are clearly in the details. One may infer that methods for data collection should be defined in the project’s planning phases, based on the advice “to think about data early on,” but, beyond this, it is unclear how one should address and evaluate the data that is collected. Additionally, no directions are given that specify what type or types of data should be collected, or how, and no information is offered that articulates how this data should or might need to be analyzed. No theoretical framework is suggested, much less established, that might guide approaches for thinking about or contextualizing the social (or economic, environmental or political) domain within which the project will evolve. Without better direction, it is unreasonable to expect designers to be able to apply this information accurately, much less effectively.

In contrast to Randall’s suggestions, Audra Buck-Coleman, a graphic design professor at the University of Maryland who has integrated the social sciences into her practice, discusses three conditions that designers should address to accurately and effectively measure impact. The first is to ensure that whatever social factors being examined and interrogated are not already occurring before a given design intervention is introduced; the second is to establish that social change does indeed occur as a result of implementing the proposed intervention, and that it does not happen without; the third is to eliminate any other explanations that could be identified as direct or indirect catalysts that affect change.[14] This kind of direction helps articulate, in much greater detail, how designers should measure the social impact of the products, systems and networks they develop and implement or distribute by gleaning and analyzing data through more controlled means. Specifically, these include when and how change within a given social situation occurs with and without design interventions. As effective as these approaches and methods have been shown to be, they fail to address questions that consider when and how to effectively apply these conditional measurements within the design process. Without more explicit methods and tools to help guide and inform the accurate and effective assessment of affected social changes, designers are potentially faced with outcomes that fail to meet real needs and aspirations, or that are the result of poorly framed and executed research and assessment methods, inaccurate population samples, or incomplete findings. Coleman argues that, in design, “the issue is not a lack of methods but [a] valid application of them.”[15]

Conversely, the design perspective does offer valuable insight and guidance for social participation and engagement through the use of design models—among them participatory design[e] and co-creation,[f]—that encourage and enable stakeholder involvement throughout the creative process. The use of a human-centered design approach is also often advised, which is an iterative, heuristically guided processg that prioritizes public participation in various stages of a project’s development by incorporating a feed-back loop with stakeholders throughout its duration and implementation. This approach emphasizes the need for the designer(s) to think strategically, and to consider holistic methods to guide design decision-making as the design process evolves to examine systems of design artifacts as a means to yield a desirable outcome, rather than focusing on the outcome itself. More recently, codesign models[h] have been introduced and practiced within the discipline and can be particularly beneficial in social design endeavors. Both of these design models value participation, collaboration, and community engagement in the support of a more inclusive design process, which can contribute to a deeper understanding of project needs, expectations, and desired outcomes. All of these are relevant components that potentially can contribute to the success of social design projects.

Examining Social Impact Assessment through the Social Science Lens

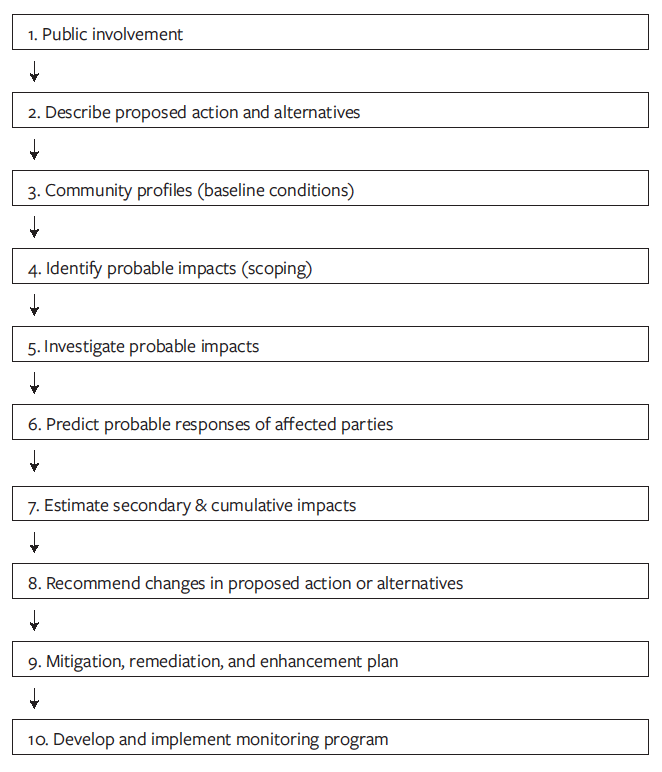

In the social sciences, impact assessment is measured through scientific evaluation, according to an evidence-based research methodology, to demonstrate affected change. According to two particularly important and influential documents from the social impact assessment field, the Guidelines and Principles for Social Impact Assessment (1995) and its updated format, Principles and Guidelines for Social Impact Assessment in the USA (2003), the social consequences of any given range of work can be measured and evaluated based on standard methods for gauging and mitigating the impacts of ‘planned interventions.’i The documents include a framework (Figure 1), prepared by the Interorganizational Committee on Principles and Guidelines (icgp) for measuring impacts that can be adopted and applied across disciplines. It is a comparative model, iterative in practice, that outlines procedural steps for “analyzing, monitoring and managing the intended and unintended social consequences, both positive and negative, of planned interventions and any social change processes invoked by those interventions.”[16] The primary purpose of this framework is to aid practitioners in their attempts to maximize positive impacts and minimize the negative. The framework and supporting literature highlight key components that should be integrated into a design process to improve methods, tools, and techniques for evidence-based research and analysis of social impact assessment for graphic designers.

The social impact assessment process begins by developing a public involvement program consisting of “those who will hear, smell, or see a development,”[17] and all other interested and affected stakeholders of a planned intervention. The literature states, “once identified, representatives from each group should be systematically interviewed to determine potential areas of concern/impact, and ways each representative might be involved in the planning decision process.”[18] This participatory method overlaps guiding principles from the design perspective and serves as a reminder of its relevance in social impact assessment processes. Public involvement of diverse stakeholders and the planning and integration of participation throughout the process should be determined in initial phases of development. The literature also emphasizes key areas of vulnerability in population sampling that decision-makers should regard. It states that “some groups low in power that may be adversely affected [by a planned intervention] are rarely early participants in the planning process.”[19] This means that the public involvement program should proactively try to ensure that all identified interested and affected groups, including those community groups and individuals that may be more challenging to find and recruit, be included in the process.

Often evolving simultaneously with the design process, the social impact assessment process includes phases for defining and framing the proposed intervention. Additionally, a baseline study, or community profile, of the community at stake is conducted in order to understand the “existing conditions and past trends associated with the human environment.”[20] The baseline study examines cause, serving as a “before snapshot” of the pre-conditional landscape, which will be used later in the process as a baseline against which relative success can be measured. These steps establish the groundwork for planning and conceptualizing a project. They also provide the relevant details to confirm (or not) whether affected changes may be happening within a given social situation prior to the instantiation of the design intervention—an important condition that, if not diligently verified, can invalidate findings.

The scoping phases in the social impact assessment process include identifying and investigating probable impacts and predicting potential responses to impacts. This phase investigates the short-, medium-, and long-term impacts that are probable, likely or unlikely, and why they are, based on the proposed design intervention outlined. The literature states, “the probable social impacts will be formulated in terms of predicted conditions without the actions (baseline condition), the predicted conditions with the actions and the predicted impacts that can be interpreted as the difference between the future with and without the proposed action.”[21] This comparative function describes the provision for measuring cause and effect. For social design endeavors, scoping will result in one or more societal impact objectives, or what aspects of a given situation designers will attempt to change as they plan, implement and assess the work they produce. It will also guide and inform what designers and their collaborators assess during the impact analysis phase(s) of this process. In identifying what areas of impact should be investigated, potential indirect and/or longer-term impacts may also need to be considered. Scoping phases can also inform whether the proposed interventions should be reconsidered.

The social impact assessment process concludes with mitigation and monitoring phases, which are defined at a point in the process when decision-makers have addressed probable impacts and agree to move forward with the planned intervention. The mitigation plan is created to reduce adverse impacts if they should arise, while the monitoring plan provides evidence-based research methods (data types, sources, an analysis plan, and population samples) for measuring real-time impacts as they occur and throughout a designated duration of time following the planned design intervention. Particular attention should be placed on what needs to be measured, how it will be measured, who will collect data and when, and who will assess it. The literature also states that “monitoring and mitigation should be a joint agency and community responsibility,”[22] recognizing the need to detail who is responsible for what monitoring and mitigation procedures, but also advocating for shared ownership of the analysis process. Additionally, the documentation states, “trust and expertise are key factors in choosing the balance between agency and community monitoring participation.”[23] This shared ownership of the analysis process can help foster unbiased findings by incorporating a checks-and-balances procedure between the designer and the community of stakeholders he or she has been working with.

These final phases of the social impact assessment process are often missing entirely from design reports, either because they are not being implemented, or they are not being implemented correctly, or they are not being documented and presented in such a way that the findings are made available to the public. In particular, monitoring, and the documentation, analysis, and presentation of the formulation and execution of the design project are essential if designers want to discuss, conclude, and disseminate findings about the affected change of their design work in broader contexts. It should be compared with cause (from the baseline study) to establish whether affected change occurs (or not). The results of this step will either support or oppose one’s claim of having facilitated positive social impact.

The Blended Perspective

The following revised methodology integrates the findings as viewed through each of the varied lenses of social impact assessment. The result is a ‘blended’ perspective—a revised process that accounts for more rigorous standards for measuring social impact in the design discipline. The steps, outlined below, are organized in a sequential format, however, it is likely that some steps overlap, happen simultaneously, and/or repeat as needed. To better understand a generalized order of operations, each step is organized into a category, where each category is more or less linearly organized, and each step within the category may happen interchangeably as needed until completion. Within each category, the steps are identified, defined and supported with actionable items. This blended perspective may be used by researchers, educators, practitioners, and students to effectively assess social impact in graphic design projects as a major outcome of their work.

I. Participation

Invite the Public. Public involvement should include a balanced pool of participants that honestly and ethically represent all interested and affected groups of a proposed design intervention or action, with particular attention given to vulnerable and/or under-represented groups.

- —Identify all interested and affected groups of a proposed design intervention.

- —Invite the public and recruit participants.

- —Identify the scale and breadth-of-scope at which these groups will engage with the project throughout its duration.

Form a Stakeholder Committee. A stakeholder committee is a specific group of participants identified from the public involvement program that will engage with the project during its planning, implementation, and monitoring phases. It should include a representative from all the interested and affected groups and should be consulted often throughout the process.

- —Determine a representative from each group identified from the public involvement program.

- —Verify the level of participation of each representative.

Define roles & responsibilities. Roles and responsibilities should clearly outline participation needs and expectations early in the process, recognizing different levels of interactions and exchanges.

- —Define the roles and responsibilities of designers and other specialized experts, as well as community participants and any other groups identified in the public involvement program.

- —Include a timeline that specifies expectations and deadlines for all agencies and individuals involved.

II. Research & Framing

Form a research strategy. The research strategy should carefully craft a plan to understand the community that will be affected by and that will affect the design intervention, contextualize its proposed action, and inform and guide the societal impact objectives in consideration.

- —Conduct a literature review (critically analyze data, documents, history, and/or other secondary sources that may offer insights about how to and how not to plan and facilitate or operate the design intervention).

- —Collect records of similar case studies, including reports with any monitored societal impacts.

- —Conduct field research with public involvement groups and individuals (interviews, meetings/charettes, surveys, observation, etc.).

Define the project. The project is the design intervention or action. It may also be referred to as the designed artifacts or outcomes, design systems, policies, experiences, and/or interactions you plan to implement. It should be clearly defined to understand the parameters and goals as well as the associated audiences and community groups at stake.

- —Define the design intervention or action.

- —Consult the stakeholder committee for feedback and input.

Identify and investigate societal impact objectives. The societal impact objectives are specific project goals that address the social, cultural, and other identified impacts you hope to achieve, based on the design planned intervention or action. These goals are measured in monitoring phases to assess affected change. It is helpful to recognize that there are many levels of impact that you could address, but that you do not need to address them all. Designers should investigate need, and weigh that against plausibility to prioritize and choose impacts for their projects.

- —Identify and investigate societal impact objectives with associated audiences and community groups.

- —Consult the stakeholder committee for feedback and input.

III. Design & Planning

Develop the project. Depending on the particular nature of the project, the creative development process will progress as it is affected and influenced by various methods, and it may take on a variety of different forms, but, generally speaking, it should evolve from initial brainstorming to conceptualization and final realization in an iterative, heuristically informed way.

- —Conceptualize and finalize the design intervention or action.

- —Present, prototype, and test the project with a committee of key stakeholders to ensure credible, authentic feedback and input.

- —Design all relevant details associated with the planning and/or implementation of the project.

Create a monitoring plan. The monitoring plan is the assessment strategy for measuring the affected change (impacts) wrought by the implementation of the design intervention or action. It should be defined prior to implementation, and include what data types will be collected and why these are essential (and how these should be mapped to societal impact goals). It should also include who will collect the data, when and how long it will be collected, who will analyze it, and how it will be analyzed.

- —Define the data types and their sources, based on your design intervention, societal impact objective(s) and whatever, relevant contextualizing information was provided by associated audiences and community groups.

- —Design the research instruments for data collection (interviews, surveys, etc.).

- —Define how long you will collect data, who will collect what data, and who will analyze data.

Define Population Sample(s). Population sample(s) represent the entire population affected by the design intervention or action. Likely, this may include participants from the public involvement program and the stakeholder committee. It may also include random sampling, which helps to guarantee that the selection process is without bias. A strong population sample usually includes many participants that represent a balanced pool of the associated audiences and community groups.

- —Define population sample(s) for data collection.

- —Create methods and tools for recruitment of population sample(s).

Conduct a baseline study of the community. The baseline study involves data collection to understand and document the pre-existing conditions of a community (conditions without the proposed design intervention or action). It should examine the relevant factors associated with the community, the social issues in question, and the audiences and community groups at stake. The data collected is used to compare against the results of the monitoring phase to assess affected change.

- —Design the baseline study (this may overlap with designing the monitoring plan—a future step).

- —Collect data based on defined data types, sources, and strategies for baseline study.

- —Confirm control strategies to ensure that the affected changes you hope to achieve will not occur based on other circumstances beyond the defined design intervention or action.

IV. Intervention & Monitoring

Implement design intervention or action. The proposed project should begin and be executed as determined during its developmental phases.

- —Execute the project using the methods, mediums, and other associated logistics as they were defined and contextualized during the developmental phases.

Monitor impact. Monitoring is the process of gathering and recording data based on the research methodology articulated in the monitoring plan. This process begins with the implementation of the project, and continues for the duration of time defined by the monitoring plan. All data and methods for collecting data should be recorded and executed exactly as specified by the monitoring plan.

- —Collect and record data according to the monitoring plan and the configurations inherent in the population sample(s).

- —Document effect (account for post-conditional measures).

Measure affected change. Affected change is measured by comparing the documented effect (recorded during monitoring) against the baseline assessment (recorded from the baseline study).

- —Analyze data according to the specifications articulated in the monitoring plan.

- —Compare pre-conditional measures (posited as a baseline study) with post-conditional measures (as derived through monitoring).

- —Conclude whether affected changes occur (or not), and at what scale.

V. Presentation

Document findings. An impact report that depicts the findings from the project should clearly demonstrate affected impact based on relatively measured cause and effect, and employ a comparative model.

- —Document the evaluation and assessment methods that were formulated and operationalized.

- —Document the population sample(s) and the rationales and methods for creating them.

- —Document cause and effect; account for pre-conditional and post-conditional measures.

- —Document affected change. Account for conditions that demonstrate the effect was not present prior to the intervention and ensure that it was not influenced by any other possible causes.

Present findings for Public Distribution. Findings should be presented, published, and distributed in a manner that ensures audiences not only understand the affected change(s) and the factors and conditions that shaped it (or them), but also how metrics were employed to yield specific conclusions.

- —Prepare findings so that they can be effectively shared with the public.

Conclusions

By integrating an in-depth, evidence-based social impact assessment into design processes, designers are more likely capable of addressing and contributing to the complexities of systemic design problems that require interdisciplinary and collaborative methods to facilitate effective problem-solving. They are also more likely to be able to confront the critical social, technological, economic, environmental, and/or political issues that encompass the discipline of design (and that design decision-making also affects) by assessing, documenting, and reporting on the short-, medium-, and long-term implications that developing and producing design work may have on social groups, economic sectors, political endeavors, environmental initiatives and other large-scale contexts. Further, the application of this revised methodology may also assist in elevating the roles and responsibilities of designers, situating them as decision-makers, facilitators, leaders and agents of positive change in their communities. It can also contribute to the betterment of the design discipline and profession as a whole by raising the level and expectation of evaluation standards in design to meet those of other academic and professional disciplines. By integrating the language and methods of neighboring disciplines like the social sciences, designers may be able to reach audiences beyond the design discipline who may not know or recognize the benefits of design interventions beyond what they perceive to be artistic expression. Utilizing the methods described in this piece to assess the social impact of design, if planned and operated correctly, can also potentially hinder the exploitation of the communities that would be affected by a given design intervention. These types of methods provide an objective measurement toolkit that helps keep the priorities of particular social groups in the forefront of design strategies and processes, and ensures that their outcomes are understood within these contexts.

By employing these kinds of broadly informed approaches and methods, graphic designers can imbue themselves with the ability to take on complex and challenging social issues in their work in ways that prioritize social impact as a major outcome of what they produce and implement or distribute. Drawing from the social sciences to address social impact assessment standards across disciplines, this paper describes a revised design methodology for planning, implementing, and assessing social impact in graphic design projects. The result is a ‘blended’ perspective that includes the steps and action items necessary for effectively measuring positive change that meets the requirements of critically rigorous evaluation standards.

References

- [ICGP] The Interorganizational Committee on Principles and Guidelines for Social Impact Assessment. “Guidelines and principles for social impact assessment.” Environmental Impact Assessment, 15.1 (1995): pgs. 11-43.

- [ICGP] The Interorganizational Committee on Principles and Guidelines for Social Impact Assessment. “Principles and guidelines for social impact assessment in the USA: The Interorganizational Committee on Principles and Guidelines for Social Impact Assessment.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 21.3 (2003): pgs. 231-250.

- Buck-Coleman, A. “Assessment considerations for social impact design.” In Developing Citizen Designers, edited by E. Resnick, pgs. 284-285. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury, 2016.

- Davis, M. et al. “AIGA Designer 2025: Why design education should pay attention to trends,” AIGA Design Educators Community, August 21, 2017. Online. Available at: https://educators.aiga.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/DESIGNER-2025-SUMMARY.pdf (Accessed January 4, 2019).

- Gosling, E. “What Will A Designer + Their Job Look Like in 2025?,” AIGA Eye on Design, 25 October, 2017. Online. Available at: https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/what-will-a-design-job-in-2025-look-like/ (Accessed January 4, 2019).

- Heller, S. & Vienne, V., eds. Citizen Designer: Perspectives on Design Responsibility. New York, NY, USA: Allworth Press, 2003.

- Lasky, J. “Design and Social Impact: A Cross-Sectoral Agenda for Design Education, Research, and Practice,” The Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, in conjunction with the National Endowment for the Arts and The Lemelson Foundation, New York, 2013. Online. Available at: https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Design-and-Social-Impact.pdf (Accessed January 4, 2019).

- Papanek, V. Design for the Real World, 2nd edition. London, uk: Thames and Hudson, 1984.

- Resnick, E. “What is design citizenship?” In Developing Citizen Designers, edited by E. Resnick, pgs. 12-13. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury, 2016.

- Sanders, E. B.-N. & Stappers, P.J. “Co-creation and the new landscapes of design” CoDesign, 4.1 (2008): pgs. 5–18.

- Shea, A. “Anatomy of the socially responsible designer.” In Developing Citizen Designers, edited by E. Resnick, pgs. 20-21. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury, 2016.

- Simonsen, J., & Robertson, T. (Eds.) The Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design. London, UK: Routledge International Handbooks, 2012.

- Vanclay, F. “International Principles for Social Impact Assessment.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 21.1 (2003): pgs. 5-12.

- Wilson, E. “What is Social Impact Assessment?” Indigenous Peoples and Resource Extraction in the Arctic: Evaluating Ethical Guidelines, January 15, 2017. Online. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315550573_What_is_Social_Impact_Assessment/download (Accessed May 22, 2019).

Biography

Cat Normoyle is an Assistant Professor of Graphic Design in the School of Art & Design at East Carolina University, in Greenville, North Carolina, USA. Her research and creative activity explore how design can make a positive difference in communities when guided by designers as a catalyst for change. She believes that these changes can be manifest as emerging theories, and they can also be operated as practices and abetted by technologies. She is interested in a broad range of design topics, including social design and impact, community engagement, digital experiences and technology, and speculative design. Her work is interdisciplinary, experimental, collaborative; at its core, it is strategic. It ranges from the physical to the digital, from the static to the dynamic, and from the two-dimensional to the three-dimensional.

She has presented her work nationally and internationally at notable design conferences such as the Cumulus Association (International Association of Universities and Colleges of Art, Design and Media), the EAD (European Academy of Design), DEL (Digitally Engaged Learning Conference), the AIGA Design Educator’s Community, the Design Principles & Practices Research Network, and Design Incubation (Research in Communication Design). She is a two-time alumnus of Design Inquiry, a non-profit educational organization devoted to researching design issues in intensive team-based gatherings. She has published in numerous design books and journals, including the chapter titled, “Motion Design in the Context of Place,” which appeared in the book “The Theory and Practice of Motion Design: Critical Perspectives and Professional Practice,” which was published by Routledge (R. Brian Stone and Leah Wahlin, eds.) in 2018. She also published the scholarly paper, “A Catalyst for Change: Understanding Characteristics of Citizen-driven Placemaking Endeavors Across Diverse Communities,” which won an International Award for Excellence in 2016 in The Design Principles and Practices collection Vol. 10.

Originally from Boston, she has a bachelor’s degree in Industrial Design from Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, and a Master’s of Fine Arts degree in Graphic Design from Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Prior to working in academia, Normoyle worked at Trend Influence, an Atlanta-based, brand strategy and innovation agency, where she worked with Fortune 500 companies such as Coca-Cola, Toyota, and Levi’s.

Notes

- a

With the progression of the graphic design discipline, the terms “graphic design” and “graphic designer” have also evolved to include others that attempt to capture this expanding role. They include visual communication design, user-experience design, experience design, interactive design, service design, and systems design, to name a few. It’s important to note that each of these terms also may infer some slight variances based on specializations within the discipline and profession.

- b

This is an annual online report (published online) sponsored by AIGA (the U.S.-based professional association of design that sponsors the publication of Dialectic), and Google that surveys design professionals in the US.

- c

Social design is referenced by many names, also known as public-interest design, socially responsive design, transformation design and humanitarian design; These terms are often used interchangeably, but also infer slight variances in meaning and implication. For more information about social design, see: “Design and Social Impact: A Cross-Sectoral Agenda for Design Education, Research, and Practice.” Online. Available at: https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Design-and-Social-Impact.pdf# (Accessed January 4, 2019).

- d

‘for good’ references AIGA’s Design for Good initiative that supports graphic designers engaged in projects that foster social change. For more information and supporting materials on the initiative see: AIGA Design for Good. Online. Available at: https://www.aiga.org/design-for-good (Accessed January 4, 2019).

- e

Much more information about participatory design is available in The Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design edited by Jesper Simonsen and Toni Robertson. Simonsen, J., & Robertson, T. (Eds.) The Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design. London, UK: Routledge International Handbooks, 2012.

- f

Seminal information about Co-creation can be derived from the journal article “Co-creation and the new landscapes of design” by Elizabeth B.N. Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers. Sanders: E. B.-N. & Stappers, P.J. “Co-creation and the new landscapes of design” CoDesign, 4.1 (2008): pgs. 5–18.

- g

In the context of this piece, “heuristically guided” refers to methods for informing decision-making processes that are informed by practical approaches, such as trial-and-error, to assess the efficacy of specific aspects or features of a particular procedure, protocol, or prototype. Heuristic approaches are not intended to be guided by logic, nor are they intended to produce perfect or optimal results. Rather, they are a means to facilitate problem-solving that yields a satisfactory outcome, one that produces a result that is “good enough.” Heuristic approaches sometimes involve making educated guesses, or operating according to “rules of thumb,” or intuitive judgements.

- h

Codesign models vary slightly from the human-centered approach, particularly in the intervention phases where participants/stakeholders work directly with designers to produce and implement interventions, sharing authorship and ownership of the final work.

- i

The SIA literature refers to planned interventions as “policies, plans, programs, and projects (the 4 Ps).”

Wilson, E. “What is Social Impact Assessment?” Indigenous Peoples and Resource Extraction in the Arctic: Evaluating Ethical Guidelines, January 15, 2017. Online. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315550573_What_is_Social_Impact_Assessment/download (Accessed May 22, 2019).

Davis, M. et al. “AIGA Designer 2025: Why design education should pay attention to trends,” AIGA Design Educators Community, 22 August, 2017. Online. Available at: https://educators.aiga.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/DESIGNER-2025-SUMMARY.pdf (Accessed January 4, 2019).

Gosling, E. “What Will A Designer + Their Job Look Like in 2025?,” AIGA Eye on Design, October 25, 2017. Online. Available at: https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/what-will-a-design-job-in-2025-look-like/ (Accessed January 4, 2019).

Lasky, J. “Design and Social Impact: A Cross-Sectoral Agenda for Design Education, Research, and Practice,” The Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, in conjunction with the National Endowment for the Arts and The Lemelson Foundation, New York, 2013, p. 6. Online. Available at: https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Design-and-Social-Impact.pdf# (Accessed January 4, 2019).

Papanek, V. Design for the Real World, 2nd ed. London, UK: Thames & Hudson, 1984, p. 55.

Heller, S. “Introduction to first edition.” In Citizen Designer: Perspectives on Design Responsibility, 2nd ed., edited by S. Heller & V. Vienne, p. 17. New York, NY, USA: Allworth Press, 2003.

Resnick, E. “What is design citizenship?.” In Developing Citizen Designers, edited by E. Resnick, p. 12. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Garland, K. “First things first,” The Guardian, November 29, 1963. Online. Available at: http://www.designishistory.com/1960/first-things-first/ (Accessed January 4, 2019).

Taplin, D., Clark, H., Collins, E., and Colby, D. “Technical Papers: A Series of Papers to support Development of Theories of Change Based on Practice in the Field.” Actknowledge and The Rockefeller Foundation, April 10, 2013. Online. Available at: http://www.actknowledge.org/resources/documents/ToC-Tech-Papers.pdf (Accessed May 21, 2019).

“How to engage Design for Good in your community,” AIGA Design for Good. Online. Available at: https://www.aiga.org/design-for-good (Accessed January 4, 2019).

Buck-Coleman, A. “Assessment considerations for social impact design.” In Developing Citizen Designers, edited by E. Resnick. New York, NY, USA: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Vanclay, F. “International Principles for Social Impact Assessment.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 21.1 (2003): p. 6.

[ICGP] The Interorganizational Committee on Principles and Guidelines for Social Impact Assessment. “Guidelines and principles for social impact assessment.” Environmental Impact Assessment, 15.1 (1995): p. 25.