Speculative City: Critical Speculation in Defense of Design’s Material Expertise

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Many design practices have recently shifted from industrial-era, object-centric, disciplinarily segregated outcomes of their design processes toward the production of data-driven products, services, and systems. While this shift demands that designers engage intelligently and critically with socio-technical systems, the planning and production of those sites, situations and experiences where systems directly and indirectly affect human experience remains the primary domain of design. The increased productization of information and the data-driven mutability of material objects are coupled with broadly rising concerns about the social and ethical implications of embedding networked interfaces and objects in almost every facet of contemporary life. At the current rate of change in design practice—and amidst competing concerns about the future—how can today’s design educators effectively prepare students for lives and careers which can hardly be imagined?

This theoretical speculation reflects on the pedagogical value of incorporating Speculative Design in the context of undergraduate design education. Based on the author’s experiences in creating, teaching, and eventually exhibiting undergraduate student work produced from a Speculative Design seminar-studio hybrid course, the methods, mindsets, and outcomes observed during this learning experience are critically examined as a means to address two overarching questions posed to the facilitation of university-level design education. They are: 1) How can design students engage in projects that employ object-making capacities as a means to engage in systems-level investigations, in ways that make object-systems interdependencies explicit? 2) How can design students engage in projects that make the risks, negative possibilities, unintended consequences, or social “trade-offs” of designing and implementing new technical objects explicit?

The author summarizes that a Speculative Design framework was indeed successful in addressing these concerns, as evidenced by the learning outcomes experienced by students who were enrolled in the aforementioned Speculative Design seminar-studio hybrid course. Each of these outcomes demonstrates a clear understanding of the reciprocity of influence between systems and objects. This is evinced in the students’ creation of material forms imbued with enough social, political, or ideological presence to engage competing perspectives and values. These outcomes are critically addressed by the author in an attempt to codify relative effectiveness in evaluating critical speculations as student design work.

In conclusion—and in hindsight—the success of this pedagogical experiment hinged on two critical factors. First, the epistemological and ontological boundaries of Speculative Design as a category were kept loose, inviting a variety of methods and outcomes that might occupy a broader discursive territory. This invited students who were enrolled in the Speculative Design seminar-studio hybrid course to imagine different, possibly more “practical” applications of concepts derived from a speculative mindset. First, this enabled them to explore the potential for speculative methods to be integrated into hybrid forms of future practice. Second, the students’ existing skills in material production were entirely necessary to guide their creation of successful speculative objects and media. The need to account for and interrogate these two factors indicates the need for design educators to retain fostering and asserting the material expertise of design in their teaching, even as that expertise is applied toward shaping, manipulating, implementing, or making use of complex systems. The capacity to navigate between systems-level and object-level design interventions, and to deliver principled responses at both levels, must be built into design education today to ensure future practitioners have the capabilities to continually respond to new risks and opportunities as design practices expand the scopes of what they develop, produce and disseminate in “ways that aggregrate information, products, and services from different providers in response to the needs and interests of various user groups.”[1]

Introduction: Design in Transition, Expansion, and Uncertainty

In response to an ongoing and uneven transition to a post-industrial information economy, many design practices have shifted over the past few decades to constructing and facilitating information or communication services, systems, and other immaterial flows. The field once known as graphic design has expanded to include producing digital communication products, services, tools, and other information-driven mediations for every facet of life. Many graphic or communication design practices now operate firmly in the space of product design—well beyond previous roles in branding, marketing, or communicating about products. The fields of industrial and fashion design often shape material objects that are operated on, by, or through data control networks—sometimes as service offerings. This shift has seen the design disciplines that produce the physical forms of material culture join extant areas of study as diverse as Human-Computer Interactions, Anthropology, Psychology and Cybernetics. These movements blur distinctions between industrial-era, object-centric disciplinary divisions (e.g., graphic, industrial, or fashion design) while demanding intelligent engagement with the human-system interfaces that give form to everyday life. These interfaces may be developed and designed as material objects, networked objects, or not as objects at all. This combination of increased productization of information and the data-driven mutability of material objects has contributed to a prevailing user-centered mindset in much of design practice and education. This mindset has codified processes and methods to squeeze value out of “experiences,” increasingly transforming experiences into commodities. Meanwhile, concerns are generally mounting about the social and ethical implications of all these data-collecting interfaces and objects being embedded into the most personal strata of everyday life.[a] These concerns appear in direct contradiction to user-centered design approaches as they are utilized to maximum use time, attention, and data sharing as revenue potential. At this rate of change—and amidst so many competing concerns—how can design educators prepare students for lives and careers which can hardly be imagined today?

While many competing demands have been set forth, two salient arguments about the needs that contemporary design education must now satisfy stand out:

- Design students today need to become familiar with methods necessary to engage, think, and operate at the level of systems—moving beyond the skills of crafting objects alone.[2]

- Design students today need methods, frameworks, and approaches to think more critically about the impacts of their work, evaluating risks, negative impacts, and potential for social harms. This is particularly important as designers engage new, emerging, and unprecedented technologies.

Design Education: Preparing for the Unimaginable

While systems-level thinking is critical for contemporary design students, the capacity to craft thoughtful, responsible “objects” or “experiences” should not be left behind. In fact, this seems only more valuable given the risks and opportunities of emerging and future materials (biological, genetic, hybrid, etc.), production methods (additive manufacturing, robotics, genetic engineering, etc.), and computationally-informed experiences (artificial intelligence, machine learning, autonomous objects, etc.) that stand poised to re-orient almost all forms of human-material relations.[b] Designers will need both the systems knowledge to navigate new possibilities and the material knowledge to shape human interfaces with those systems—physical or otherwise.

In this context, focused, critical thinking signals a new set of concerns. As design disciplines achieve more authority in deciding what gets produced and how, increased responsibility falls on designers for the implications and outcomes of these decisions.c At what cost is the designer willing to satisfy the “user” as the center of concern? To address that question first requires a broader view of the systems that support the interactions between the user and designed object or experience under consideration. Understanding ethical risks and opportunities in the unfolding complexities of new socio-technical systems will surely present an evolving challenge to designers and design educators. Yet, producing sites of mediation—those points “where society and matter exchange properties”[3] when systems impact the human experience—will remain the domain of design. Preparing future designers for such rapidly evolving risks and opportunities so that they might deliver principled responses is a primary concern for design education today.

Assessing these concerns, two questions emerge to guide pedagogical thinking as it affects design education:

- How can design students engage in projects that employ object-making capacities as a means to facilitate system-level investigations, making object-system interdependencies explicit?

- How can design students engage in projects that make the negative possibilities, unintended consequences, or social “tradeoffs” of new technical objects and experiences explicit?

Speculative Design as Pedagogical Framework

Introducing Speculative Design to undergraduate students in Communication, Industrial, and Fashion Design provided the means to test pedagogical responses to these questions. In the early 21st century, Speculative Design[d] emerged as one of several new competing discourses in design practice and research. Its genesis within the larger discourse of Critical Design combined a desire to “find ways of operating outside the tight constraints of servicing industry,”[4] a new intellectual project for design, and a response to the perceived lack of criticality when engaging new and emerging technologies.[e] Defining any category of design is complicated by the fact that design itself is simultaneously an activity, a body of outputs, and a discourse. For current purposes as articulated in this article, focus will remain on the activity of Speculative Design, which can be defined as a research methodology that utilizes design practices to materialize proposals for planning, making, and doing that account for both the risks and the opportunities inherent in future life. In particular, it involves assessing design’s role in domesticating new technologies into everyday life. Speculative Design employs a design-led approach[5] to research, which results in material proposals—typically objects or mediated experiences. In formulating curriculum for this new course, Speculative Design was used as a framework to engage systems thinking and deeper criticality into a curriculum otherwise entrenched in user-centered methods that primarily yielded commercial outputs. Working with students already well-versed in object-making presented an opportunity for deep inquiry into social and technical systems with the confidence that students could find their way back to material or media outputs.

In the course taught by the author titled Speculative City, undergraduate students used a Speculative Design methodology to investigate, imagine, and then produce critical proposals for “urban futures.” As the city is increasingly formed by digital communication and information networks, interfaces with these networks—through personal, wearable, or networked objects and services—are becoming more formative of the human-scale urban experience. This course encouraged students to question how designers today might enact opportunities for more critical—indeed, political—discourse on what the city of the future could be. They were tasked to pay particular attention to possibilities and risks of technologies on the horizon that do not yet inhabit everyday life but may soon transform it. In hindsight, it appears the course went beyond—or perhaps, outside—the typical confines of Speculative Design, likely due to methods which were informed from a variety of other design practices.[f] Regardless, critical analysis of the social impacts of technology—a common concern of Speculative Design[6]—fostered reflection about the opportunities and risks afforded by these future tools, processes, “material palettes,”[7] and the sensibilities they could stimulate for future designers and future publics.

Speculative City

The course was a seminar-studio hybrid. As a seminar, students engaged in diverse readings, viewings, and research presentations. Excursions into Science & Technology Studies, Social Theory, Actor-Network Theory, and Cyborg Anthropology, among others, provided valuable new perspectives—not necessarily manifested as methods or theories—from different disciplines. These perspectives sensitized students to relationships between cultural, economic, political, and technical forces, and, in particular, illuminated how designed objects and experiences both respond to and incite changes in social structures, affordances, perceptions, and identities. This produced new vocabulary for expansive and sometimes contentious dialogue over a vast range of topics. Concerns about the behaviors and logics of social media or dating in the age of Tinder might be expected and even provide solid ground for design intervention. However, given fairly limited time for iterative and sustained engagement, topics of inquiry opened up more uncertain and often more personal musings. For example, what might it be like if—or maybe when—having sex with robots is a normalized social activity?[8]

Growing out of that shared vocabulary, studio work followed a rigorous methodology of “disciplined imagining”[g] to ground future speculations in evidence of unfolding social, cultural, and political trajectories. While topical research and discussion would typically inform a studio project, in this case, the studio projects became that discourse. Speculative scenarios and their material forms (objects, interfaces, mediated experiences) began to slowly and iteratively embody topical ideas with enough social, political, or ideological presence to engage competing perspectives and values. These critical speculations were shaped by guiding principles that continued to develop through an interplay between the ongoing re-imagining of future scenarios and prototyping the objects and experiences of those scenarios. What follows is a concise overview of the methods used by the students enrolled in the Speculative City course to generate speculative future scenarios that draw clear connections between large-scale systems and principles by which students could realize actionable design challenges.

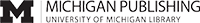

Observation & Mapping the Dark Matter

Students began with direct observation in the city. In particular, they were instructed to seek examples of social rituals embodied by technical objects or systems, incomplete adoptions of new technologies and infrastructures, or the human capacity to adapt to incipient scenarios. These observations produced the starting point for what has turned out to be the most valuable step in this process, Mapping the Dark Matter.[h] In this exercise a single object, scenario, or interaction collected from observation, is analyzed to reveal many interconnected systems that support, produce, and limit it. By interrogating these systems, any ordinary object or scenario—no matter how banal—becomes a “black box”[9] of unknowable quantities of history, politics, and social-material connections. While the exercise defies completion, students are instructed to rigorously map system-object interdependencies to bring disparate objects and social circumstances into a unified field.[i] Historical phenomena, political ideologies, economic models, material and production flows, aesthetic concerns, legal constraints, and future postulations are mapped out along distinct lines of inquiry. By doing so, the mutability of such complex systems is revealed, and all system-object relationships are rendered as contingent. Making relationships visible, students could see connectedness, identify opportunities and limitations, and begin to imagine how even very subtle systemic shifts could lead to substantially different outcomes. In this manner, these interrogations allowed students to start the process of re-imagining those systems and their dependent objects, scenarios, or experiences.

Emerging Technologies & Speculative Visions

These system-object imbroglios were then coupled with emerging technologies. By challenging the dominantly optimistic narratives of technological innovation, students probed multiple possible scenarios—Utopias, Dystopias, and “Middletopias”—at the intersection of their social and technical topics. The “Middletopia” scenario becomes key: it is here that the utopian and dystopian potentials of these scenarios must be negotiated, and the potentially harmful or uncertain negative impacts are rendered as “tradeoffs” for the positive opportunities.[j] Every “present” is another state of becoming.

Material Realization of System-Object Discourse

The final step was to create material objects or experiences that propose future possibilities still wrought with ethical uncertainties. Having done the work of building up future “realities” at the human scale, students could apply practical design skills for prototyping, production, and iteration of designed objects or mediated experiences. However, to act on these possibilities, students had to commit to values or principles derived from their topical research as articulated through the discourse-object dialogue. Successful projects made evident the “tradeoffs” that these new objects or experiences demand—tradeoffs such as decreased privacy, sacrificing personal autonomy, or retreating from difficult political decisions. Prototypes supported use case scenarios in plausible, if unlikely, contexts that make their situated complexities evident.

Dread & Desire

In 2017, the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning at the University of Cincinnati hosted the International Association of Societies of Design Research (IASDR) conference. In conjunction with the conference, select projects from this course were presented in an exhibition titled Dread & Desire: Urban Futures at the Scale of the Human Body.[10] Organizing and designing this exhibition provided the opportunity to shift perspective from pedagogy to curation. Five emergent topical themes were used to organize the exhibited projects, and visitors to the exhibition were given opportunities to engage with the themes through a variety of interactions with the projects, self-guided workshops, and discussion areas. Rather than explicate these topical themes, a discussion of select projects from the exhibition will demonstrate the breadth of student outcomes. Each case study identifies how the project’s effectiveness as a critical speculation is determined, connecting system-object dependencies while making social tradeoffs evident. In doing so, this creates a codified system of analysis for this kind of student design work.

Viable Solutions for Problems that Don’t Yet Exist (and Maybe Don’t Need to)

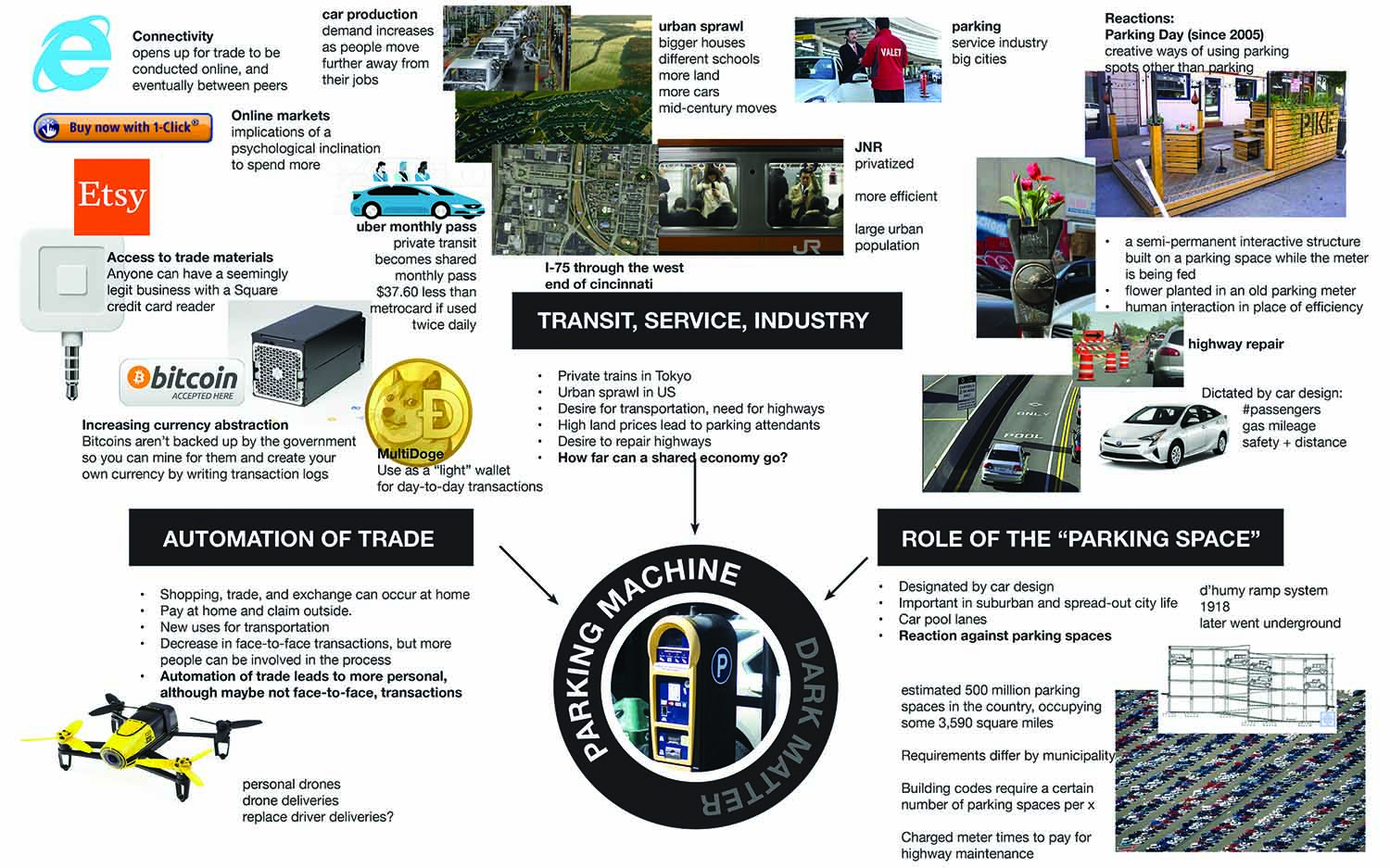

Industrial Design student Joe Frankl began his research with an investigation of signs and systems by which urban populations broadcast vulnerability. This prompted concerns for the waning capacity for humans to read each other’s social needs due to the increased mediation of social experiences (his principle). Recent studies suggest that children using screen-based devices up to 7 hours per day demonstrate a diminished capacity to read nonverbal cues or decipher emotions from face-to-face interactions.[11] What this will mean for future generations is yet to be understood. Frankl’s S.I.A. (Sensory Interaction Aid) proposes a multi-sensory translation system to augment the perception of nonverbal communication through a suite of digitally-sensing wearable devices. The project solves a problem that doesn’t exist—at least, not yet. However, considering the vast array of socially mediating products and services already in use, this hardly seems a stretch. Of course, this problem could be avoided altogether by simply ensuring that children spend less time on screens. S.I.A. produces an opportunity to reflect on these choices: design new technical devices for our decreasing social sensitivities or prevent future problems through behavioral change. Perhaps this future problem would be best addressed without new technical objects—a point made tangible by rendering what that technical solution might be.

The Elusive and Destructive Desire called “Self”

Fashion Design students today have plenty of anxiety about the social and environmental impacts of their industry—and for good reason. Yet, the challenges of labor conditions, resource diminishment, environmental costs, material waste, and so on are confronted by exploding urban populations in search of constantly new forms of social- and self-identity. Fashion Design students Katherine Allen and Margy Groshong engaged the speculative methodology to research these competing forces, while considering potential impacts of contemporary research in neuroscience, genomics, and biotechnology.[k] Their projects, 46 and Unisuit, take two distinct approaches to postulating social realities in which “Self” is understood very differently. Together, the two projects indicate contradicting views of sociability and individuality that are confronted, augmented, and potentially exploited by wearable objects. Presented together as a catalog, the viewer is essentially invited to “pick one” in a radically reduced choice architecture. By rendering such divergent approaches to the production of “Self”—returning attention to natural bodies or the value of inward, mental focus—Fashion Design is re-conceived, insisting on its still critical social role while imagining future possible functions.

Revealing Root Problems through Comically Reductive Symptom-Solutions

As students begin to see competing desires or conflicting systems impact the human experience (via the knowledge they constructed for themselves during their engagements with the Mapping the Dark Matter portions of this learning experience), decisions about what “should” or “should not” be affected by objects of mediation are immediately political. In this context, “political” denotes the ways in which power relations and influences are exerted through material experience. While this territory is much broader and more nuanced than “politics”—the institutional processes of governance—this space also presents an opportunity for students to examine the limits and opportunities of designed systems and objects. Speculative City student Evan Hoffman used the Speculative Design methodology to examine the still unfolding implications of the 2010 Citizens United ruling in the United States. This U.S. Supreme Court ruling allows corporations nearly free reign in financially supporting political causes or candidates.[12] By taking the notion that American citizens vote with their wallets literally, PollWatch makes intersections of economic and political systems visible—even at the tiny scale inherent in a single citizen’s actions. The underlying assumption that citizens would have fully transparent knowledge of corporate interests manifesting themselves in the political landscape may seem desirable, yet the oversimplification of these issues should remain obvious. In this case, engaging Solutionism[l] to point it out presents a valuable tactic for challenging the hubris of design interventions that would claim to operate objectively, openly, and transparently amidst so much complex contestation. While not exactly satire, seeing PollWatch as a critical provocation redirects the viewer to the initial problem—the influence of corporate interests on American politics—while asking if design can reasonably and responsibly intervene at all.

Long-Term Implications: What if We Keep Following this Logic?

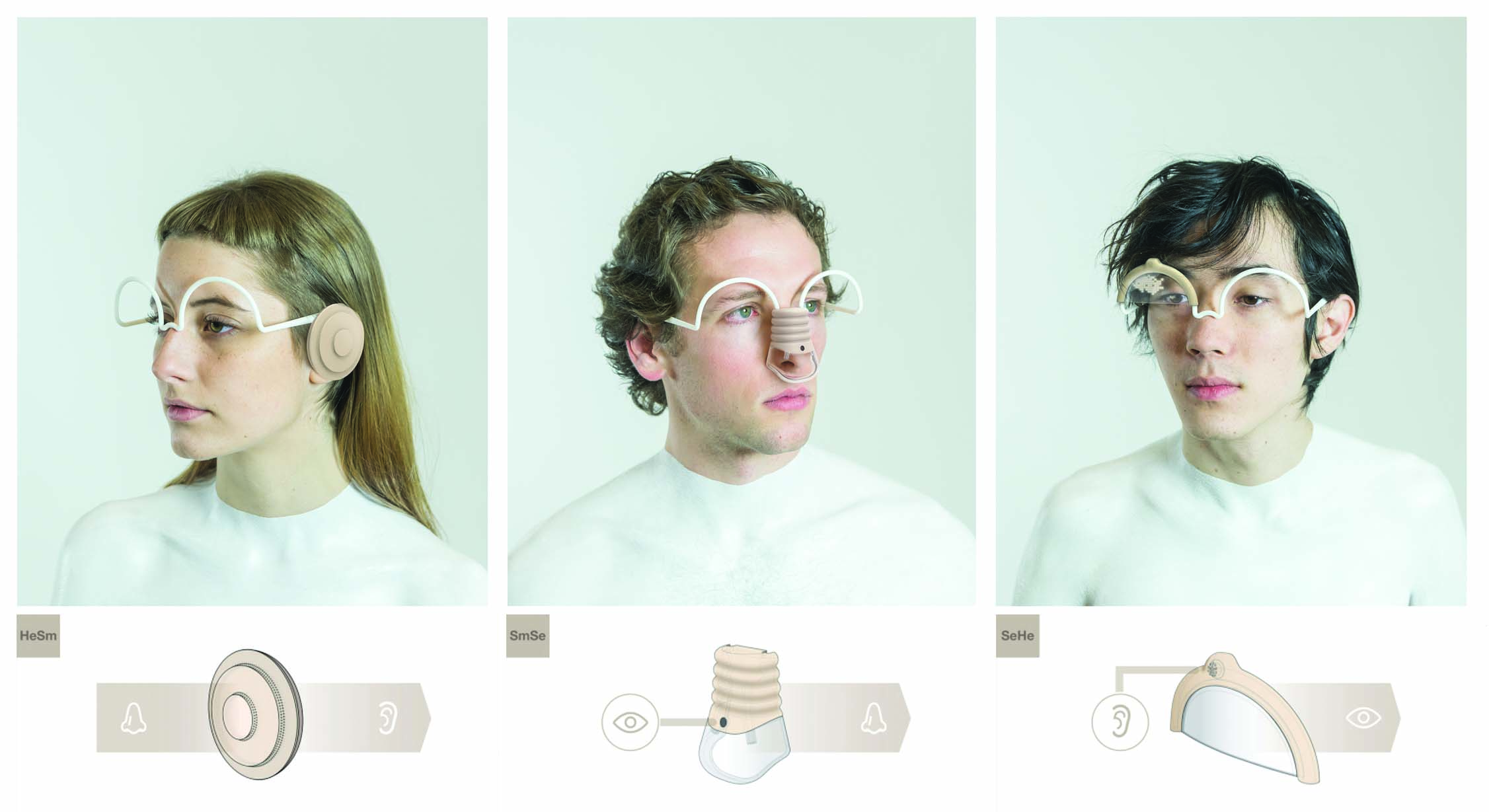

Engaging undergraduate students today in rigorous critique of the social, political, and economic implications of technology equates to spending a lot of time questioning, challenging, and wondering about the future of social media. While social media nurture communities around common interests, cultural perspectives, and other social identifiers, they have also created divisive rifts—perhaps most visible in the U.S. during the run-up to the 2016 presidential election (which coincided exactly with the facilitation of the Speculative City class). The ability to curate social reality easily produces “echo chambers and cybercascades,”[13] that silence differing perspectives. How does the possibility of erasing social discomfort or friction—by blocking, hiding, or deleting certain content—diminish social and political potential? Fashion Design student Erika Frondorf and Industrial Design student Anissa Pulcheon worked together to examine the logics and assumptions that social media have already instilled in their everyday social experiences by taking a long view of where these logics and assumptions might lead in the future. This project takes affordances of social media interactions online and plays them out in the new and still emerging mediated spaces of augmented reality. By demonstrating what the long-term implications of social behaviors afforded by current technologies might become within newer ones, both the social and technical systems can be reassessed—as they are now and as they might become.

Conclusion: Decentering the User, Asserting Expertise

Students emerged from this experience having developed a robust methodology to confront shifting social, political, and economic landscapes and to engage new or uncertain technologies through a principle-centered approach to design, rather than satisfying the desires of individual “users” at any cost. Inasmuch as a University education remains distinct from vocational training, this seems invaluable in preparing students for lifelong practice—particularly, as the possibilities of future practice are unimaginable today.

As an experiment, the course hypothesized that Speculative Design could engage undergraduate design students in investigating system-object interdependencies while generating personal critical perspectives on the implications of designing new technologies into everyday life. This hypothesis appears validated by the student outcomes analyzed here—each of which demonstrates a clear understanding of the reciprocity of influence between systems and objects through material forms with enough social, political, or ideological presence to engage competing perspectives and values. However, two further observations arise from these conclusions.

First, while the intent and approach of Speculative Design may differ from those in a design studio geared toward solving problems or creating products, many of the practical and research methods employed were similar. In this way, the course reinforced the potential for applying research from direct observation, visualizing secondary research (e.g. Mapping the Dark Matter), developing personae & scenarios, constructing narratives for use case scenarios, and ultimately gaining the knowledge necessary to build convincing prototypes. Yet, these have been applied in a new context. That shift of context engaged students in critical, creative, and productive capacities outside the hegemony of a user-centered mindset.

Second, the intent and approach of Speculative Design provided a specific starting point for this curriculum; however, what resulted has gone beyond the typical confines of Speculative Design. Speculative practices are often narrowly focused on provocative, even dystopian propositions extrapolated from emerging science and technology. However, these student outcomes live more squarely on the “social” side of the socio-technical spectrum. This may be a difference of degree, but by demonstrating possibilities that do not depend entirely on future technologies, many projects indicate potential for application in a broader—perhaps “more practical”—set of circumstances. Mapping the dark matter, uncovering non-object solutions, articulating long-term implications of socio-technical behaviors to expose future harms, constructing false limitations or comic reductions for the sake of gaining new insights on complex issues: these methods can clearly be integrated into diverse practices.

The hybrid seminar-studio nature of this course seems to have been important to its success. Topical discourse on intersecting forces that shape social, political, and economic life and object-making—now and into the future—and object-making were undertaken simultaneously, putting the two into an iterative dialogue. This forced students to confront systemic forces by re-centering their object-making sensibilities beyond the “desires” of the individual user. Instead, a principle-centered approach has emerged in which object-system tensions result in situated design proposals that let their uncertainties, angst, and even their potential for “dread” be known.

The Speculative Design framework asserts a design-led, expert-mindset,[14] positing the designer as an expert at a time when user-centered practices dominate much of design education. As valuable as user-centered practices may be for developing products and services, they can also instrumentalize design into a narrow focus on usability and utility. This strips some of design’s potential for developing principled intellectual projects. In design curricula, if user-centered design is positioned as the primary (or only) disciplinary framework, future forms of practice are certain to be limited. As a seminar-studio hybrid expanding from a Speculative Design framework, the Speculative City course demonstrates another possibility. It argues for the intellectual potential still evident in objects and object-making by engaging design students in principled material responses to object-system dependencies.

It’s clear that similar efforts are unfolding across the design education landscape. Evidence of the diaspora of Speculative Design can be found scattered across recent conferences and symposia;[15][16][17][18] exhibitions;[19][20][21][22] and discourse in diverse publications.[23][24][25][26] In the United States, several design schools now offer speculative design degrees or concentrations.[27][28][29][m] Debates will surely continue about their value, codifications, and taxonomies; yet, it also seems clear the territory will continue to grow, mature, and transform.

The Designer 2025 document recently published by AIGA[30] advises that design education must shift away from “physical objects and their production.”[31] However, that argument seems short-sighted.[n] This course has only deepened the conviction that design education cannot stop addressing the pivotal impacts of objects or the specific nature of interfaces with systems. Every human contact with a system (touchpoint, interface, experience ...) requires deliberation and expertise in defining its specific conditions. Every “smart” or “connected” object has the potential for oppressive information control, dangerous persuasion, unwarranted surveillance, fostering addictive behaviors, or ... not. These possibilities are intimately tied to both systemic and object-based specificities as determined by the principles applied to their design (e.g., convenience at the cost of control, efficiency at the cost of choice). Designers are uniquely positioned to respond and act accordingly. The capacity to navigate between systems-level and object-level design responses, and to deliver principled responses at both levels, needs to be built into design education today to ensure future practitioners have these capacities to continually respond to new risks and opportunities. To start, students need methods for understanding system-object dependencies at play and methods for critically imagining and assessing potential risks. As the roles and responsibilities for designers continue to evolve, design educators should not forget the potency of objects. Let’s also not forget the material expertise of design.

References

- AIGA. “AIGA Designer 2025: Summary Document,” AIGA Design Educators Community (blog). 22 August, 2017. Online. Available at: https://educators.aiga.org/aiga-designer-2025 (Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Auger, J. “Speculative Design: Crafting the Speculation.” Digital Creativity, 24.1 (2013): pgs. 11–35. Online. Available at: doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2013.767276 (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- BBC News, “Intelligent machines: Call for a ban on robots designed as sex toys,” BBC News: Technology, 15 September, 2015. Online. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-34118482 (Accessed July 6, 2018).

- Brassett, J., Fairfax, D., Gaynor, I., Kimbell, L., Malpass, M. & Tonkinwise, C. (symposium panel) “We Have Never Been Speculative Enough.” University of Arts London, 21 September, 2015. Online. Available at: http://events.arts.ac.uk/event/2015/9/21/We-Have-Never-Been-Speculative-Enough/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Bratton, B. “On Speculative Design,” DIS Magazine, February, 2016. Online. Available at: http://dismagazine.com/discussion/81971/on-speculative-design-benjamin-h-bratton/#ref6 (Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Butoliya, D. “Speculative (Post) Critical Design” Carnegie Mellon University, School of Design, 2016. Online. Available at: https://speculativecriticaldesigncmu.wordpress.com/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Charlesworth, J. “Primer 2017: A Speculative Futures Conference,” Core77, 21 March, 2017. Online. Available at: http://www.core77.com/posts/63489/Primer-2017-A-Speculative-Futures-Conference (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Colomina, B., & Wigley, M. (curators) “Are We Human?” 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, 20 October–20 November, 2011. Online. Available at: http://arewehuman.iksv.org/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Davis, M. “What Is Worth Doing in Design Research?” Keynote presentation at IASDR2017, Cincinnati, OH, USA, November, 2017.

- Dumit, J. “Writing the Implosion: Teaching the World One Thing at a Time.” Cultural Anthropology, 29.2 (2014): pgs. 344–362. Online. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14506/ca29.2.09 (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Dunne, A, & Raby, F. Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects. Basel, Switzerland, 2001.

- Dunne, A, & Raby, F. Speculative Everything. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2014.

- Dunne A., & Raby, F. “Critical Design FAQ.” Dunne and Raby. Online. Available at: http://www.dunneandraby.co.uk/content/bydandr/13/0 (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Frondorf, E. & Pulcheon, A. “XØ” on Vimeo. Available at: https://vimeo.com/216569488 (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Ghanbari, S. “New UC San Diego Visual Arts Major Emphasizes Designing for the Future,” UC San Diego News Center, 7 January, 2016. Online. Available at: http://ucsdnews.ucsd.edu/pressrelease/new_uc_san_diego_visual_arts_major_emphasizes_designing_for_the_future (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Harvard University Graduate School of Design. “Master in Design Studies: Art, Design, and the Public Domain.” Online. Available at: http://www.gsd.harvard.edu/design-studies/art-and-the-public-domain/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Hill, D. Dark Matter and Trojan Horses : A Strategic Design Vocabulary. Moscow, Russia: Strelka Press, 2015; pgs. 81–109.

- Klein, A., Geisler, T., Wirth, M. & de Smet, F. (curators) “Hello, Robot: Design Between Human and Machine.” MAK Vienna. 21 June–10 October 10, 2017. Online. Available at: http://www.mak.at/e/hello_robot (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Latour, B. “On technical mediation: philosophy, sociology, genealogy.” Common Knowledge, 3.2 (1994), pgs. 29–64.

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: an Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Lawson, S., Kirman, B., Linehan, C., Feltwell, T., Hopkins, L. (2015) “Problematising Upstream Technology through Speculative Design: The Case of Quantified Cats and Dogs” CHI '15 Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York City, NY, USA: ACM.

- Malpass, M. “Between Wit and Reason: Defining Associative, Speculative, and Critical Design in Practice.” Design and Culture, 5.3 (2013), pgs. 333–356.

- Marr, B. “Why Everyone Must Get Ready for the 4th Industrial Revolution,” Forbes, 5 April, 2016. Online. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2016/04/05/why-everyone-must-get-ready-for-4th-industrial-revolution/#178508d33f90 (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Metahaven. Black Transparency: The Right to Know in the Age of Mass Surveillance. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2015.

- MIT Media Lab. “Knotty Objects: Brick, Bitcoin, Steak, Phone,” MIT Media Lab Summit, Ica Boston and MIT Media Lab, 15-16 July, 2015. Online. Available at: https://www.media.mit.edu/events/knotty/overview (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Mitrović, I & Šuran, O. (curators) “Speculative–Post-Design Practice or New Utopia”? The XXi International Exhibition of the Triennale di Milano, Design After Design, presentation of the Republic of Croatia. National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci / Cavallerizze, 2 April–12 September 2016. Online. Available at: http://speculative.hr/en/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Morozov, E. To Save Everything, Click Here. New York City, NY, USA: Public Affairs, 2014; p.6.

- Neeley, J. P., & Montgomery, E. “Speculative Design: Futures Prototyping for Research and Strategy.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference. 1 (2016): pgs. 567–568. Online. Available at: doi.org/10.1111/1559-8918.2016.01133 (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Sanders, L. “An evolving map of design practice and design research.” Interactions, 15.6 (2008): pgs. 1–7. Online. Available at: http://www.dubberly.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/11/ddo_article_evolvingmap.pdf (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Sueda, J. (curator) “All Possible Futures.” SOMArts Cultural Center. 14 January–13 February, 2014. Online. Available at: http://allpossiblefutures.net/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Tharp, B., Tharp, S. “Discursive Design's Reflexive Turn?,” Core77. 29 May, 2017. Online. Available at: http://www.core77.com/posts/57317/Discursive-Designs-Reflexive-Turn (Accessed July 6, 2017).

- Tonkinwise, C. “Design Fictions about Speculative Design,” Modes of Criticism, 2 March, 2015. Online. Available at: http://modesofcriticism.org/design-fictions-about-critical-design/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- Tonkinwise, C. “Just Design: Being Dogmatic about Defining Speculative Critical Design Future Fiction,” Medium (blog). 21 August, 2015. Available at: https://medium.com/@camerontw/just-design-b1f97cb3996f (Accessed July 6, 2017).

- Verbeek, P. P. Moralizing Technology: Understanding and designing the morality of things. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

- Wizinsky, M. “Dread & Desire: Urban Futures at the Scale of the Human Body.” University of Cincinnati, The Myron E. Ullman, Jr., School of Design (exhibition catalog). October, 2017. Online. Available at: doi:10.7945/C2BD6W (Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Wolpert, S. “In our digital world, are young people losing the ability to read emotions?” UCLA Newsroom, 21 August, 2014. Online. Available at: http://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/in-our-digital-world-are-young-people-losing-the-ability-to-read-emotions (Accessed July 6, 2017).

Biography

Matthew Wizinsky is a designer, researcher, and Assistant Professor in the School of Design at the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning (DAAP) at the University of Cincinnati (UC) in Cincinnati, Ohio, USA. His projects live at various intersections of participatory design, interaction design, exhibition design, and speculative design. Professor Wizinsky’s research collaborations typically apply community-engaged participatory methods toward domains that comprise contemporary conceptions of “the public” and/or “the city” and integrate experimentation with digital media. Current engagements include participatory design with HIV survivors to create a public history of HIV in America and working with adolescents from the South Side of Chicago to transform public historical research into speculative visions for improved future health amidst threats of a changing climate.

Notes

- a

When executives of major tech companies—some of the most powerful companies in the world—begin openly criticizing the negative impacts of their own products, “strange things are afoot.” Price. R. “Apple CEO Tim Cook: I don't want my nephew on a social network.” Business Insider. 19 January 2018. Available at: http://www.businessinsider.com/apple-ceo-tim-cook-doesnt-let-nephew-use-social-media-2018-1 (Accessed April 14, 2019).

- b

Collectively coined as the coming “4th Industrial Revolution.” Marr, B. “Why Everyone Must Get Ready for the 4th Industrial Revolution,” Forbes, 5 April 2016. Online. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2016/04/05/why-everyone-must-get-ready-for-4th-industrial-revolution/#6394c07d3f90. (Accessed February 17, 2019).

- c

According to philosopher of technology, Peter-Paul Verbeek: “Even when designers do not explicitly reflect morally on their work, the artifacts they design will inevitably play mediating roles in people’s actions and experience, helping to shape moral actions and decisions and the quality of people’s lives.” Verbeek, P. P.Moralizing Technology: Understanding and designing the morality of things. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press, 2011, p. 90.)

- d

Speculative Design evolved from Critical Design—a term coined in the 1999 book Hertzian Tales by Anthony Dunne and further developed in the 2001 book Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby. According to Dunne & Raby: “Critical Design uses speculative design proposals to challenge narrow assumptions, preconceptions and givens about the role products play in everyday life.” Dunne A., & Raby, F. “Critical Design FAQ.” Dunne and Raby. Online. Available at: http://www.dunneandraby.co.uk/content/bydandr/13/0; Accessed April 14, 2019. Matt Malpass further distinguishes Speculative Design by its specific focus “on science and technology, establishing and projecting scenarios of use; it makes visible what is emerging... [.]” Malpass, M. “Between Wit and Reason: Defining Associative, Speculative, and Critical Design in Practice.” Design and Culture, 5.3 (2013), pgs. 333–356.

- e

“It grew out of our concerns with the uncritical drive behind technological progress, when technology is always assumed to be good and capable of solving any problem.” Dunne, A, & Raby, F. Speculative Everything. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2014; p. 34.

- f

This can likely be at least partly attributed to the instructor (author) largely inventing the curriculum out of uncertainty of how the learning objectives might be achieved.

- g

“Speculations are forms of disciplined imagining, methods by which designers force themselves to think in more ambitiously counterfactual ways. Speculations try to push beyond current expectations and trending futures; they expand the sense of what is possible.” Tonkinwise, C. “Just Design: Being Dogmatic about Defining Speculative Critical Design Future Fiction,” Medium (blog). 21 August, 2015. Available at: https://medium.com/@camerontw/just-design-b1f97cb3996f (Accessed July 6, 2017).

- h

The title was inspired by Dan Hill’s adoption of this term from theoretical physics, referring to the undetectable or untraceable forces that shape matter. Hill, D. Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary. Moscow, Russia: Strelka Press, 2015; pgs. 81–109.

- i

I have since discovered this exercise is similar to the “Implosion Project” by anthropologist Joseph Dumit, based on his reading of Harraway and Deleuze. Dumit, J. “Writing the Implosion: Teaching the World One Thing at a Time.” Cultural Anthropology, 29.2 (2014): pgs. 344–362. Online. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14506/ca29.2.09 (Accessed 15 December 2017).

- j

These methods have since been shared more comprehensively in workshops conducted at the AIGA 2016 National Design Conference, 17–19 October, 2016, Las Vegas, NV; the IASDR 2017 International Design Conference, 31 October–3 November, 2017, Cincinnati, OH, USA; Social Innovation and Social Justice: Rethinking Design Anthropology, 28–30 March, 2018, Cincinnati, OH; and Primer 2018 Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA.

- k

This included material research including experiments in growing bio-textiles from kombucha and other bacteria. This was not a technique the class materials were designed to support, but that’s what YouTube does really well.

- l

“Solutionism, thus, is not just a fancy way of saying that for someone with a hammer, everything looks like a nail...it’s also that what many solutionists presume to be ‘problems’ in need of solving are not problems at all...” Morozov, E. To Save Everything, Click Here. New York City, NY, USA: PublicAffairs, 2014; p. 6.

- m

Multiple graduate faculty advisors in the STAMPS School of Art & Design list “Speculative Design” among their areas of expertise. STAMPS School of Art & Design, “MDes Faculty Advisors,” University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. Online. Available at: https://stamps.umich.edu/graduate-programs/mdes_faculty (Accessed December 15, 2017).

- n

Of particular concern is the statement “The end goal of design is ‘good enough for now.’” This sounds like the recipe for a disastrous acquittal of designers from prolonged engagement in and long-term responsibility for the impacts of their work, situated as it must be in specific human and material contexts. AIGA, “AIGA Designer 2025: Summary Document,” n.p.

AIGA. “AIGA Designer 2025: Summary Document,” AIGA Design Educators Community (blog). 22 August, 2017. Online. Available at: https://educators.aiga.org/aiga-designer-2025 (Accessed April 14, 2019).

Latour, B. “On technical mediation: philosophy, sociology, genealogy.” Common Knowledge, 3.2 (1994), pgs. 29–64, 41.

Dunne, A, & Raby, F. Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhauser Verlag, 2001; p. 59.

Sanders, L. “An evolving map of design practice and design research.” Interactions, 15.6 (2008): pgs. 1–7. Online. Available at: http://www.dubberly.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/11/ddo_article_evolvingmap.pdf (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Malpass, M. “Between Wit and Reason: Defining Associative, Speculative, and Critical Design in Practice.” Design and Culture, 5.3 (2013), p. 335.

Bratton, B. “On Speculative Design,” DIS Magazine, February, 2016. Online. Available at: http://dismagazine.com/discussion/81971/on-speculative-design-benjamin-h-bratton/#ref6 (Accessed April 14, 2019).

“Intelligent machines: Call for a ban on robots designed as sex toys,” BBC News: Technology, 15 September, 2015. Online. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-34118482 (Accessed 6 July 2018).

Latour, B. “On technical mediation: philosophy, sociology, genealogy.” Common Knowledge, 3.2 (1994), pgs. 29–64; p. 32.

Wizinsky, M. “Dread & Desire: Urban Futures at the Scale of the Human Body” (exhibition catalog). Scholar@UC, October, 2017. Online. Available at: https://scholar.uc.edu/downloads/mk61rg97b?locale=en (Accessed April 14, 2019).

Wolpert, S. “In our digital world, are young people losing the ability to read emotions?” UCLA Newsroom, 21 August, 2014. Online. Available at: http://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/in-our-digital-world-are-young-people-losing-the-ability-to-read-emotions (Accessed 6 July 2017).

Dunbar, J. “The ‘Citizens United’ decision and why it matters,” The Center for Public Integrity, 18 October, 2012. Online. Available at: https://www.publicintegrity.org/2012/10/18/11527/citizens-united-decision-and-why-it-matters (Accessed April 14, 2019).

Metahaven. Black Transparency: The Right to Know in the Age of Mass Surveillance. Berlin, Germany: Sternberg Press, 2015.

Sanders, L. “An evolving map of design practice and design research.” Interactions, 15.6 (2008): pgs. 1–7.

MIT Media Lab. “Knotty Objects: Brick, Bitcoin, Steak, Phone,” MIT Media Lab Summit, ICA Boston and MIT Media Lab, 15-16 July, 2015. Online. Available at: https://www.media.mit.edu/events/knotty/overview (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Brassett, J., Fairfax, D., Gaynor, I., Kimbell, L., Malpass, M. & Tonkinwise, C. (symposium panel) “We Have Never Been Speculative Enough.” University of Arts London, 21 September, 2015. Online. Available at: http://events.arts.ac.uk/event/2015/9/21/We-Have-Never-Been-Speculative-Enough (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Charlesworth, J. “Primer 2017: A Speculative Futures Conference,” Core77, 21 March, 2017. Online. Available at: http://www.core77.com/posts/63489/Primer-2017-A-Speculative-Futures-Conference (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Primer2018. “Transformation & Possibilities.” San Francisco, CA, USA. 3–5, May. https://primerconference.com/2018/

Colomina, B., & Wigley, M. (curators) “Are We Human?” 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, 20 October–20 November, 2011. Online. Available at: http://arewehuman.iksv.org/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Sueda, J. (curator) “All Possible Futures.” SOMArts Cultural Center. 14 January–13 February, 2014. Online. Available at: http://allpossiblefutures.net/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Mitrović, I & Šuran, O. (curators) “Speculative–Post-Design Practice or New Utopia”? The XXI International Exhibition of the Triennale di Milano, Design After Design, presentation of the Republic of Croatia. National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci / Cavallerizze, 2 April–12 September 2016. Online. Available at: http://speculative.hr/en/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Klein, A., Geisler, T., Wirth, M. & de Smet, F. (curators) “Hello, Robot: Design Between Human and Machine.” MAK Vienna. 21 June–10 October 10, 2017. Online. Available at: http://www.mak.at/e/hello_robot (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Auger, J. “Speculative Design: Crafting the Speculation.” Digital Creativity, 24.1 (2013): pgs. 11-35. Online. Available at: doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2013.767276 (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Malpass, M. “Between Wit and Reason: Defining Associative, Speculative, and Critical Design in Practice.” Design and Culture, 5.3 (2013), pgs. 333-356.

Neeley, J. P., & Montgomery, E. “Speculative Design: Futures Prototyping for Research and Strategy.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference. 1 (2016): pgs. 567–568. Online. Available at: doi.org/10.1111/1559-8918.2016.01133 (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Bratton, B. “On Speculative Design,” DIS Magazine, February, 2016. Online. Available at: http://dismagazine.com/discussion/81971/on-speculative-design-benjamin-h-bratton/#ref6 (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Ghanbari, S. “New UC San Diego Visual Arts Major Emphasizes Designing for the Future,” UC San Diego News Center, 7 January, 2016. Online. Available at: http://ucsdnews.ucsd.edu/pressrelease/new_uc_san_diego_visual_arts_major_emphasizes_designing_for_the_future (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Butoliya, D. “Speculative (Post) Critical Design” Carnegie Mellon University, School of Design, 2016. Online. Available at: https://speculativecriticaldesigncmu.wordpress.com/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

Harvard University Graduate School of Design. “Master in Design Studies: Art, Design, and the Public Domain.” Online. Available at: http://www.gsd.harvard.edu/design-studies/art-and-the-public-domain/ (Accessed December 15, 2017).

AIGA, “AIGA Designer 2025: Summary Document,” AIGA Design Educators Community (blog). 22 August, 2017. Online. Available at: https://educators.aiga.org/aiga-designer-2025 (Accessed December 15, 2017).