The Landscape of Community and Participatory Design in Puerto Rico: A Critical Examination of the Effects of Attempting to Facilitate “Listening to Their Voices,” (“Escuchando las Voces”) the Island’s First Exhibition of Community and Participatory Design

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The exhibition was supported by the Department of Arts, Culture, and Innovation of the Municipality of San Juan, Puerto Rico, under Grant Number 2016-002866. Editorial support for the publication of this article was provided by Dialectic’s Internal Editing Team, led by Michael R. Gibson, Evelyn Denson, and the late Joan Secrest.

Disclosure Statement: The authors received a minimal honorarium for designing and organizing the exhibition.

Abstract

As of this writing in January of 2018, Puerto Rico remains beset by an ongoing financial crisis that has shaken the island economically, socially and politically since late 2005. This situation was made much worse on September 20, 2017, when the island was devastated by Hurricane María, an event that caused this crisis to become a humanitarian one as well. In view of this complex — and socio-economically staggering — situation, Puerto Rican designers are finding that they must reconsider their social, economic and, in some cases, political roles and adapt to the island’s new daily realities. This case study explores the findings of an architectural educator and a design researcher who were prompted by the current economic climate to produce a convivial[a] project to assist fellow creatives as they attempted to navigate the ebb and flow of the Puerto Rican economy and its short- and long-term effects on the daily lives of Puerto Rican citizens. This project was planned to meet two goals. The first was to provide a means to explore and experiment with collaborative methodologies. The second was to teach non-designers and practitioners how they might apply these methodologies to provide relief to particular population groups around the island who were experiencing difficult socio-economic and socio-political circumstances. It is the authors’ contention that employing the design methodology of co-creation[b] could be an effective means to allow groups of citizens working with designers to tackle day-to-day, community-based, social problems by allowing them to work on locally rooted, transformative projects.

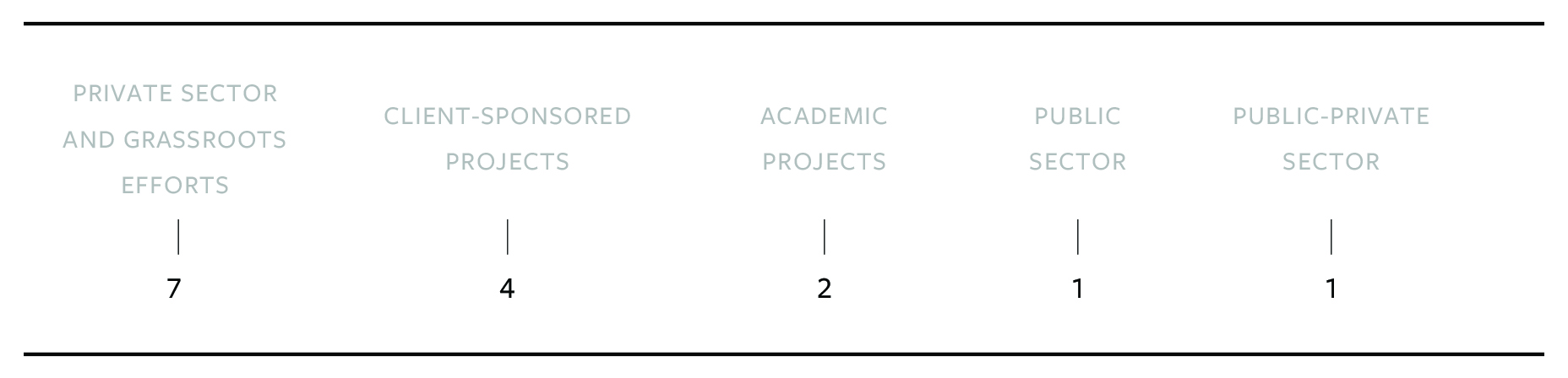

To demonstrate the results of this kind of collaboration, the authors organized the first exhibition documenting the positive outcomes of community and participatory design processes ever held in Puerto Rico: “Listening to Their Voices” (“Escuchando las Voces”). In 2015 an invitation to submit documentation of works that utilize either or some combination of both community and participatory design was sent to urban planners, artists, designers, and architects across the island. The exhibition organizers (two of whom are authors of this piece) received 15 submissions that documented projects undertaken in various locations around Puerto Rico by individual (or groups of) architects, social scientists, designers or artists. “Listening to their Voices” provided an opportunity to share critical information and experiences about these collaborative design approaches with a wider audience. Additionally, it would afford opportunities to survey the processes practitioners formulate and operationalize to create the knowledge and the skills necessary to address the effects of the by then 12-year-long financial crisis on the island’s various populations.

“Listening to Their Voices”opened in April 2017 and was suspended in September 2017 due to the damage wrought across Puerto Rico by Hurricane Maria. Despite this, the authors still felt that sharing the knowledge they were able to construct as they prepared the contents of this exhibition could prove useful. The questions that framed the authors’ inquiries regarding how and why participatory and community design could positively affect public policy change in an environment as economically bereft as Puerto Rico have yielded beneficial insights about how these processes could generalize to similar situations worldwide. Despite the problems the authors of “Listening to Their Voices” faced due to the hurricane, it is the knowledge they gained during the process of conceptualizing and realizing this exhibition that is of greatest import.

keywords: community design, participatory design, urban co-planning, Puerto Rico, toolkit, design history

Definitions and Descriptions of the Collaborative Methodologies that Guided the Projects Documented in “Listening to Their Voices”

The author acknowledge that many definitions and descriptions of Community and Participatory Design exist in the scholarly literature of design and the social sciences. For the purposes of designing, planning and implementing the “Listening to Their Voices” exhibition (and now describing them in this piece), the organizers/authors aligned themselves with what is articulated below. They felt that sharing these understandings would allow the greatest cross-sections of exhibition participants to derive benefit from them:

- Community design (CD): A methodology that focuses on developing contextual projects as a means to improve social and environmental conditions. CD encourages individual and collective participation in the preparation of small-scale projects to revitalize communities and infrastructures. Self-management and cultivating social capital are essential aspects of the comprehensive approaches used to guide the thinking required to facilitate this kind of design method. It is a participatory process in which design work becomes a training experience for citizens involved in project management wherein they are able to learn from their experiences while exploring the potential positive impact their specific contributions could have on various aspects of their communities.

- Participatory design (PD): A methodology that involves designers engaging in the design process along with a user or group of users of whatever — a space, an experience, an interface — is to be designed; hence, it is also called Co-Design. In this context, participating means becoming an active contributor to the development and implementation of a given design project. In this way, participants play an essential role in affecting how particular living spaces, systems, and objects are perceived and work in accordance with their own physical and / or emotional needs. Participation is facilitated across a contextual worktable that serves to frame the various factors and conditions that will likely affect the evolution of a given project. [1] This methodology is also fueled by open conversations that allow all of the participants involved in the design and implementation of a given project to learn from each other and to value each other’s critical input and feedback.

An Overview of Puerto Rico’s Socio-Economic Situation during the Winter of 2017-18

Puerto Rico is a small island about the size of the U.S. state of Connecticut in the northwest Caribbean Sea (Figure 1). It has been a territory of the United States since 1898, and therefore “belongs” to the U.S., but does not have the rights or representation in the U.S. Congress awarded to the fifty states. According to U.S. Census figures from 2015, the island has a population of at least 3.6 million people. Recently, migration from Puerto Rico to the United States has accelerated due to the severe financial crisis that has shaken the island for (as of the publication of this piece) almost 12 years, and, more recently, due to the general slowness of the recovery — economically, technologically and structurally — from the devastation wrought by Hurricane María. Experts estimate that by 2030, the population is expected to have dropped to under 2 million people. [2] According to the 2012 U.S. Census, only 40.5 % of Puerto Ricans are participants in the labor force, resulting in a median household income of just U.S. $19,518. “In 2014, the U.S. Census estimated that 58 % of Puerto Rico’s children live below the federal poverty level — much higher than the overall rate of 22 % of children living below the poverty line throughout the United States. Puerto Rico’s poverty rate is startlingly higher than that of any U.S. state.” [3]

With these economic factors in mind, two practitioners from the field of architecture (Edwin Quiles and Omayra Rivera) and one with a background in design research (María de Mater O’Neill) decided to come together to create a project that would present and document collaborative design methodologies as one means to address the island’s growing social, cultural and economic problems. The goals of this project then extended further to inform the Puerto Rican communities of non-designers and creative practitioners about how they might apply these methodologies, while also demonstrating the positive impact of working collaboratively under the auspices of community and participatory design. More recently, this group has realized that much of what they have learned could be of benefit to populations living in other economically distressed portions of the world.

Understanding the Approaches That Guided the Collaborative Design Methodologies Documented in “Listening to Their Voices”

The authors set out to organize “Listening to Their Voices” as it was (and still is) the shared belief of Quiles, Rivera, and O’Neill that co-creation guided by community and participatory design approaches can help guide and fuel social, cultural, and collective change in a setting such as Puerto Rico. The organizers sent out an invitation in 2015 to fellow design practitioners and researchers, urban planners, artists, and architects across the island to submit their documentation of projects that involved or utilized collaborative design methodologies they were currently working on, had worked on in the past, or that were in the planning stages. The aim of the exhibition project was to showcase, explore, and document positive effects and uses of Community and Participatory Design in Puerto Rico, as there is a general lack of local documentation on design culture — and on design in general — from this area of the world.[c] This was not only an opportunity to educate professionals and the public about the processes through which design practitioners create new knowledge and skills: it also was an opportunity to explore the potential positive affect and import of creative collaborative endeavors that had been enacted to address various aspects of the economic crisis on the island.

This was not only an opportunity to educate professionals and the public about the processes through which design practitioners create new knowledge and skills. It also was an opportunity to explore the potential positive affect and import of creative collaborative endeavors that had been enacted to address various aspects of the economic crisis on the island. The organizers / authors chose not to explore the particular suitability of Community and Participatory Design, as specific types of collaborative design methodologies, as means to guide the projects that comprised “Listening to Their Voices.” Rather, this choice was made because the essential purpose of the exhibition was to survey how these methodologies were implemented in given situations around the island. It should also be noted that the organizers of “Listening to Their Voices” had, through their years of experience as designers and design researchers working on the island, accrued significant, personal knowledge of other design practitioners who had been using these types of collaborative methodologies in their work. The fact that the community of urban planners, designers and artists who work this way is relatively small and are not spread across a large geographic area supports collaborative efforts like this in Puerto Rico.

The “Listening to Their Voices” traveling exhibition was comprised of 14 sets of interlocking, free-standing corrugated cardboard panels printed with graphics and imagery. These sets of panels (each panel measured ~48” / 122 cm x 96” / 244 cm; an average of three were used in each display) visually documented the design process and described how each exhibition contributor used participatory and / or community-based methods to guide the development of the project they chose to document (see Figure 2). The exhibition was also supported by a published catalogue containing four essays that related to collaboration, and a small “toolkit.” This toolkit consisted of 14 illustrated tactics cards (referred to henceforth in this piece as tools) that contained short descriptions of and guidelines as to how operate Community and Participatory Design tactics as recommended by each of the exhibition participants. The combined intent of the exhibition, the catalogue and the toolkit was to educate Puerto Rican design colleagues and members of diverse communities around the island about the benefits of engaging in and facilitating co-creation by recounting its history and by providing cases studies of successful co-creative projects. “Listening to Their Voices” was also supported by lectures, group discussions, a website and a Facebook page.[d]

At the time of this writing in the early spring of 2018, “Listening to Their Voices” had traveled within Puerto Rico’s capital city of San Juan to a fine arts cinema lobby, a school of architecture, the office of a nonprofit foundation, a state-operated art gallery, and a venue supported by a local board of architecture. After the originally planned tour of this exhibition had to be cancelled due to the extensive damage wrought all over the island by Hurricane María, it has continued to travel to design schools and other cultural venues in Puerto Rico outside of San Juan.

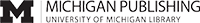

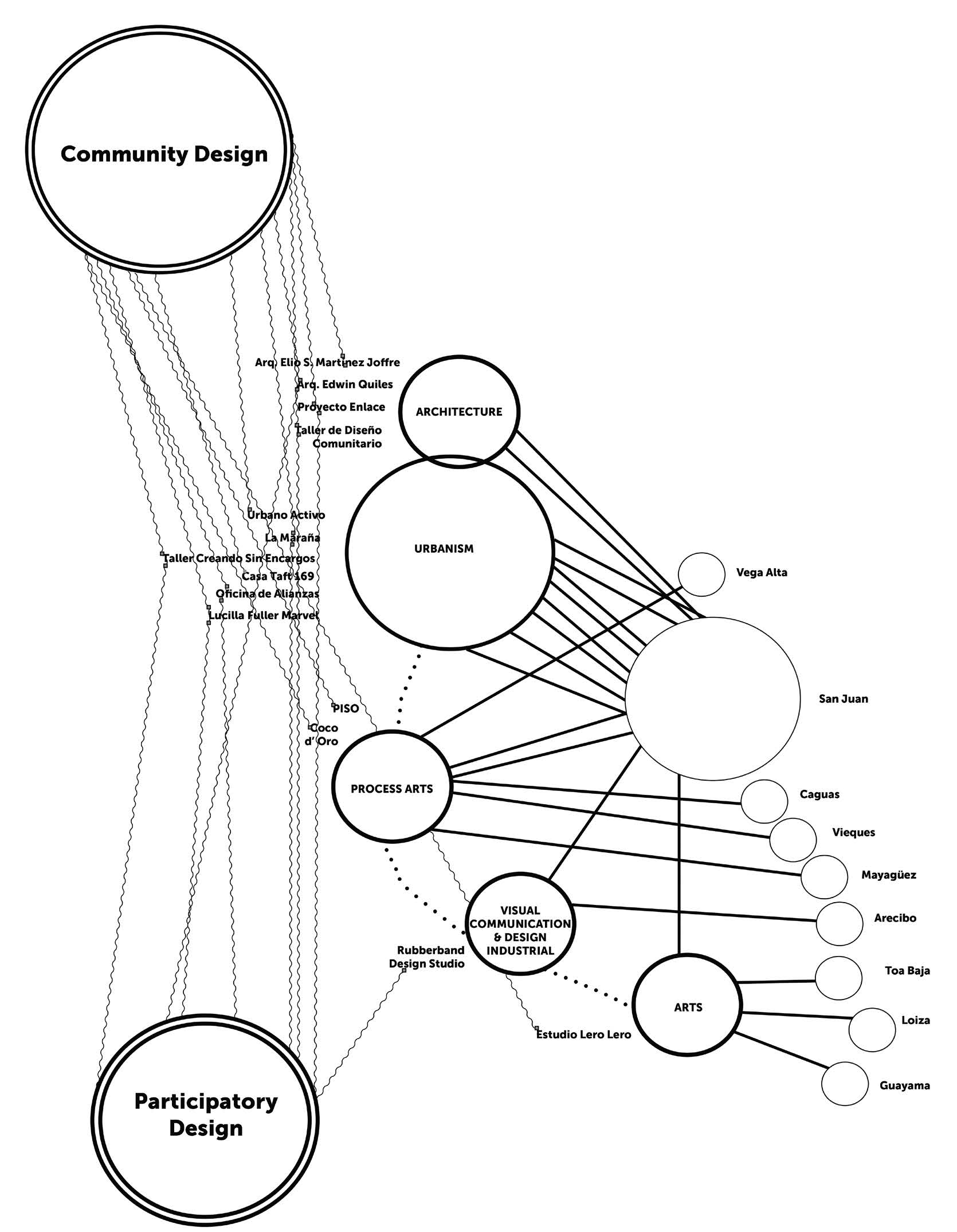

Among the 15 individuals and groups that submitted documentation of their work to be included in the exhibition were architects, visual artists, urban planners, socially entrepreneurial sociologists, a choreographer, and a visual-communications designer. The organizers also exhibited collaborative projects that they had personally been involved with. The project submissions that constituted “Listening to Their Voices” can be categorized into five groups (table 1).

Several findings and questions arose as the design and implementation of this exhibition progressed. The first two questions were factual / quantitative:

- What participatory methods, tools, and strategies have been used in design projects in Puerto Rico since the 1960s?

- Have the Community-based and / or Participatory processes been effective as means to address at least some of the social, cultural, economic or public policy issues that the communities featured in the 15 documented projects wanted to address?

The final two are formative, aimed at gaining insight:

- Are other creative practitioners (i.e., designers, architects, urban planners) learning from these collaboratively designed, urban planning or artistically rooted community projects, and, if so, how are they developing the communications skills necessary to facilitate effective collaboration with users and user groups?

- To what extent can these processes be replicated with other projects guided by different sets of parameters?

Much has been written about the ethical obligation to give users a voice in decisions that affect the conceptualization and design of their spaces, and, as an outgrowth of this, how these decisions affect their social interactions and their socio-cultural perceptions of themselves and others. [4] The low rate of citizen participation in local government and community projects in Puerto Rico may stem from a lack of knowledge about (rather than lack of interest in) civic participation in the socio-economic and socio-cultural affairs of a city or town, or of matters of governance, etc. Looking at this from another perspective, designers might consider the possibility that their roles have changed. Therefore, many of them chose to evolve their decision-making processes to take on more active roles in helping various population groups achieve their collective goals. In this way, many designers have moved toward acting as social and cultural change producers and / or facilitators. Because of this evolving and expanding new platform for designers, the facilitators of this planned exhibition sought to challenge participants to not only explore and experiment with the positive impact that collaborative design methods could have within and around a specific community, but also to affect social, cultural and even public policy change with their work.

To give readers a better understanding of the diversity of projects represented in the exhibition, the authors have chosen to showcase the examples seen in table 2.

A Brief, Localized Historical Context

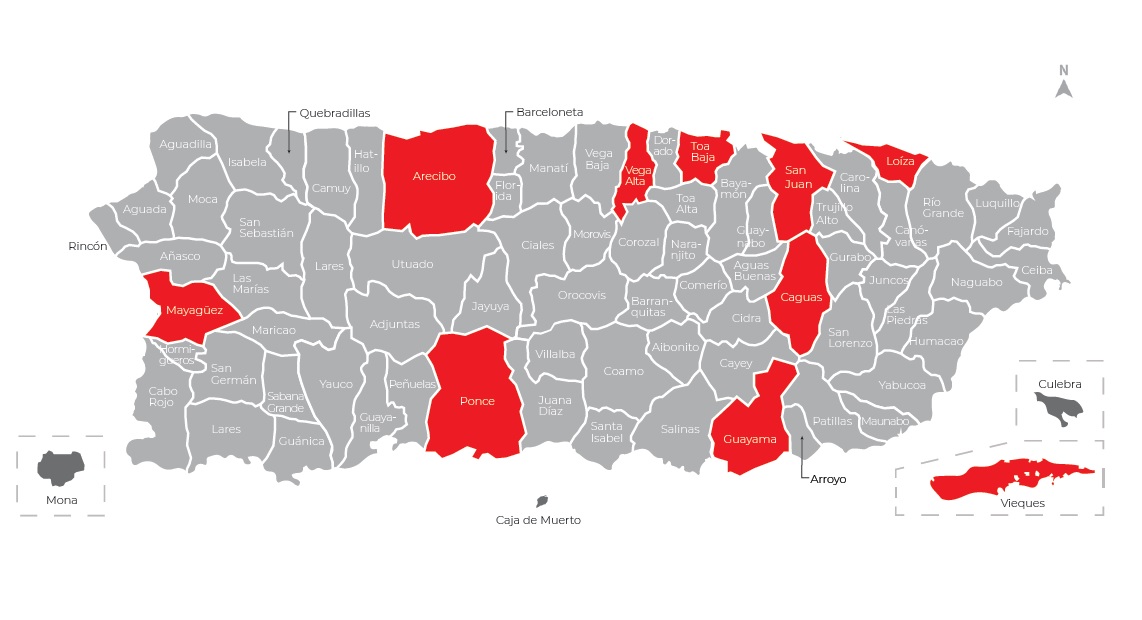

A few years after the creation of architect-based group TEAM 10 (1956)[e] and the participatory design trend taking shape in the Scandinavian countries, in Puerto Rico the Equipo de Mejoramiento Ambiental (EMA, or the “Environmental Improvement Team”) managed the first community-design project in Puerto Rico (ca. 1964) in the rural barrio of El Cerro, deep in the mountainous region of Puerto Rico in the municipality of Naranjito (reference the map on p. 127).

In Puerto Rico in the 1960s, almost parallel to the creation of academic community-based programs in the United States (which was initiated in part as a reaction to the lack of housing in poor neighborhoods), Edwin Quiles became the first architect to employ Community Design and Participatory Design, incorporating them into the design project for the Tokyo neighborhood on the Martin Peña Channel (in Puerto Rico’s capital city of San Juan). This occurred when he worked with the Volunteers in Service to Puerto Rico (VESPRA: Voluntarios en Servicio a Puerto Rico), a YMCA program — a kind of local Peace Corps — that trained community leaders and university students in community development and assigned them to communities in Puerto Rico and the eastern United States.

At about his same time, The On-Site Rehabilitation Program of the Puerto Rican Urban Renewal and Housing Corporation (Corporación de Renovación Urbana y Vivienda, or CRUV), later the Housing Department, was inaugurated in 1960 with a principle goal of rehabilitating informal settlements across the island where and when possible, rather than subject them to the U.S. federal “urban renewal” (or slum elimination) program. According to urban planner Lucilla Marvel, the emphasis was on urban planning, rather than design, and involved some community participation. [5]

When exhibition co-organizer and co-author O’Neill created the timeline diagram of milestones in community and participatory design (Figure 3), she pointed out that both in the 1960s and from early 2006 on, occurrences of Community Design and Participatory Design across Puerto Rico increased in comparison to the respective previous periods in Puerto Rican history. One of the causes for this intensification might be the extremely rapid socioeconomic transformation that occurred in many parts of the island that was characteristic of the 1960s and the 2000s. At the end of the sixties, the socioeconomic development model used in Puerto Rico began to show signs of exhaustion. [6] In 2006, the current economic crisis began in Puerto Rico, two years before the global economic crisis began, and the authors have seen an increase in the instantiation of new community-based grassroots organizations approaching social, cultural and economic matters using these methodologies during this span of time. Locally, in the 1960s and 1970s, participatory initiatives guided by an architecture and urban-planning focus increased across the island, though they declined in the 1980s and 1990s due to a lack of applicable resources. In the arts and in design practices, both of these methodologies reemerged and were applied a decade or more later. For example, in 2002 the artist Chemi Rosado Seijo (assisted by his mother Luisa Seijo Maldonado, a social worker who employed Participatory Action Research) applied this approach to an art intervention in the neighborhood of El Cerro in Naranjito, and in 2008, Rubberband Design Studio, where O’Neill is the creative director, began to apply it to product design (where aspects of it informed the creation of their toolkit of resilient thinking for designers). For more examples of how Community Design and Participatory Design were employed to affect social, cultural, economic or public policy change in Puerto Rico, refer to Figure 3.

Three Examples of Public Policy Changes that Occurred in Puerto Rico as a Result of Efforts Rooted in Participatory and Community Design

Participatory and Community design operationalized in the local context in Puerto Rico can be an innovative force. Three urban-focused projects that were documented in the exhibition were undertaken as a means to affect public policy changes:

- The Cantera Península Project (in San Juan) was initiated in 1990 to ensure the social, economic and cultural development of the Cantera Peninsula community of 10,000 residents who were living in marginal conditions at that time. The community non-profit organization the Neighborhood Council for the Development of Cantera was established in 1989 and worked with the Cantera Peninsula Comprehensive Development Company, a quasi-public corporation established by Law 20 of July 10, 1992,[f] and a community-based nonprofit, Apoyo Empresarial para el Desarrollo de la Península, incorporated in 1992, to draw up a Plan de Desarrollo Integral de la Península de Cantera (Comprehensive Cantera Peninsula Development Plan). The project was a joint effort that eventually involved four organizational partners. The boards of the public corporation and the nonprofit were comprised of representatives from the community, the government of Puerto Rico and the Municipality of San Juan, and representatives of the private, small business sector. The revitalization of the area (which is currently under way) is based on the Plan de Desarrollo Integral de la Península de Cantera (Comprehensive Cantera Peninsula Development Plan). The revitalization of the area (currently under way) under the administration of the corporation, implements programs that help guide the development of the infrastructure necessary to support the sustenance of this area’s population, together with the on-site, new, low-cost-housing complexes in which many of the residents of the Cantera Peninsula live. This has allowed hundreds of people who formerly lived along the waterways of the peninsula to remain in the vicinity rather than be forced into involuntary displacement.

- El Proyecto ENLACE del Caño Martín Peña (Martín Peña Channel) and its Comprehensive Development and Land Use Plan is also a multi-partner project, involving the Corporation of the ENLACE Project of the Martin Peña Channel, the Community Land Trust (as established by Law 489 of September 24, 2004[g]), and the organization G-8. G-8 is a non-profit entity that represents the inhabitants of the eight communities that together are comprised of approximately 25,000 people living adjacent to this historically polluted and often debris strewn channel which runs through the center of Puerto Rico’s capital city of San Juan. The majority of these people want to remain in their neighborhoods and have fought to bring about the dredging of the channel and to delineate a relocation plan that would allow them to move within the same geographic area. They continue to look for funds to support this initiative and to show evidence of how the unhealthy physical state of the Caño Martin Pena causes floods that negatively affect the quality of life and the health of those who live near it. The government initiated the project in 2002, beginning with preparation of a comprehensive plan; the law was enacted two years later and the resulting Community Land Trust (Fideicomiso del Caño Martín Peña) won the United Nations Habitat World Award in 2016. The laws setting up both the Cantera Peninsula Project and the ENLACE Project require that residents of these communities have seats on the public corporations’ boards. Both projects were designed and have been operationalized to facilitate intensive community participation. The Community Land Trust protects lots from the negative effects of real estate speculation by ensuring that the land that constitutes the trust belongs to the eight communities that together constitute the G-8, while the houses and other dwellings that occupy the land belong to families or individuals.[h] For a given lot to be sold, the entire community must agree to the parameters specified in the sale agreement.

- Puerto Rican House Bill 2583, known colloquially as Todos somos herederos (We are All Heirs), pushed by Casa Taft 169 (depicted in Figure 4), is the newest achievement in the realm of a public policy initiatives that have occurred as the result of a participatory or community design undertaking. This bill would allow ownership of properties across the island that have been abandoned or are without heirs to be transferred to the city they exist within, so these can in turn be transferred to community and grassroots organizations who can repurpose them in ways that benefit local populations. The bill became law (Law No. 157) on August 9, 2016. This has the potential to be of great benefit in many areas of Puerto Rico since the number of abandoned properties has risen dramatically due to the ongoing financial crisis that has beset the island, and that has recently been exacerbated by people leaving the country — and, in so doing, abandoning their properties — due to the lingering effects of Hurricane María.

If Puerto Rican communities can continue to address more of the primary economic and public policy issues that affect the daily lives of their populations in a participatory manner, and the government supports these initiatives, the authors hope that more Community Design and Participatory Design projects will be formulated and operationalized in ways that will yield long-term, positive results, despite the long hard road of economic crisis and Hurricane María recovery efforts that lies ahead.

Assessing the response to engaging in participatory design processes in the local landscape

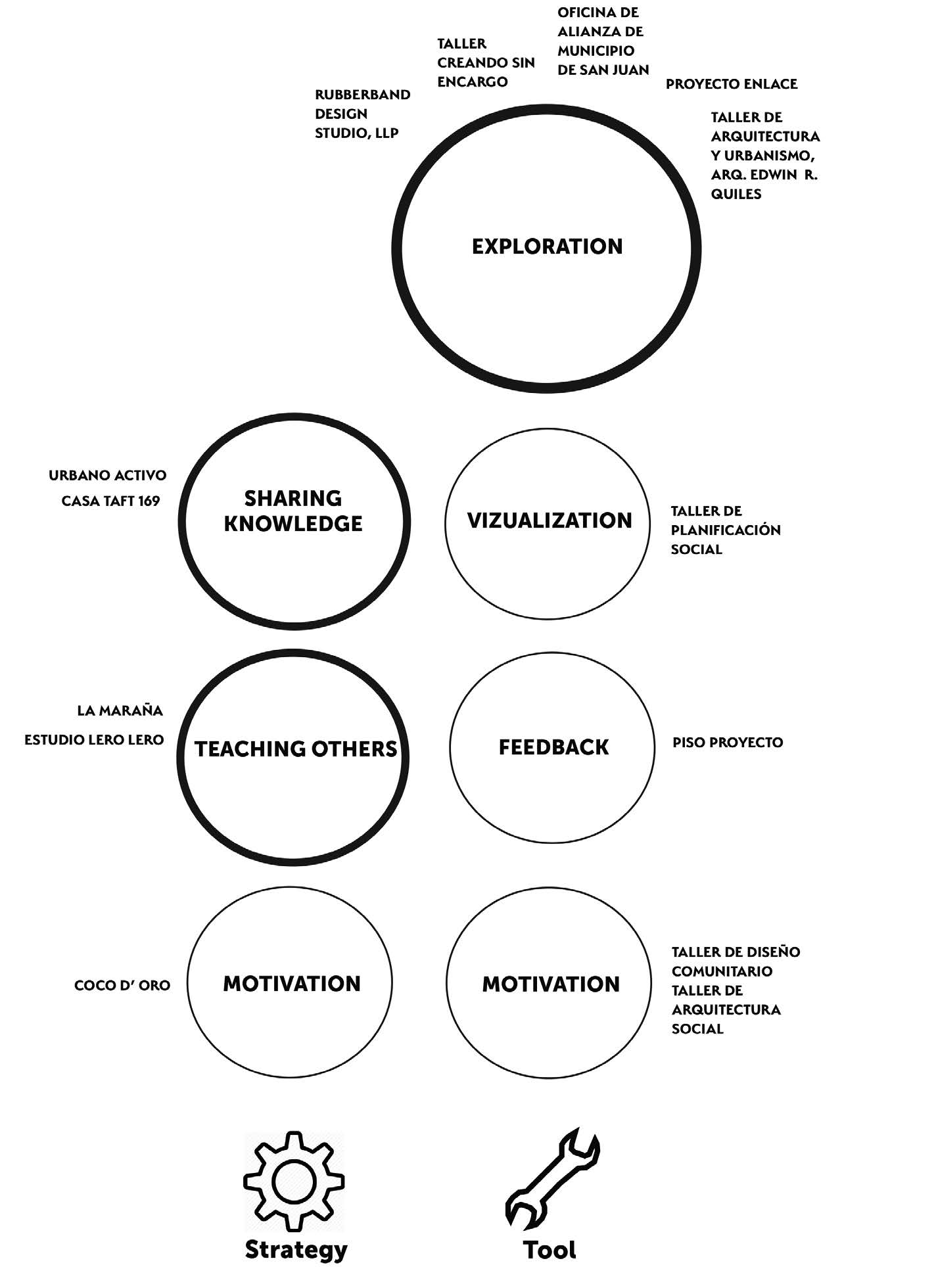

The “Listening to Their Voices” exhibition project has allowed its organizers to survey diverse array of participatory design and urban projects in Puerto Rico that have been undertaken since the beginning of the financial crisis (late 2005 / early 2006). O’Neill proposed to identify common design methods and patterns that were utilized or employed as the projects depicted in the exhibition evolved. To obtain data that would shed light on this, a questionnaire was completed by all of the exhibition participants, and semi-structured interviews were conducted between them and O’Neill. The other organizers of “Listening to Their Voices” also completed the questionnaires. The data sets that resulted from operating these data gathering activities guided the visual communication strategies that affected the design of both the informational displays and the toolkit cards (the latter evolved to function as a kind of “pocket-pack” of information). O’Neill also mapped each of the respective projects’ emphases, methodologies, and locations (Figure 5), while another mapping diagram was completed to depict the types of tactics (tools) the various participants preferred to use (Figure 6).

A summative recounting of the findings derived from the questionnaire and semi structured interviews is articulated below.

- Most of the projects presented were urban-focused, community-design based, and located mostly in Puerto Rico’s capital city of San Juan.

- Public participation tended to occur during the initial stages of design processes (i.e., during exploration of community desires for a given design outcome), although for some projects it was later, when organizers presented prototypes for community consideration. Very few of the projects were iterative, so it is not surprising that participatory design was used less.

- All participants in “Listening to Their Voices” perceived the users they worked with during the evolution of their respective projects as people, rather than as subjects of a research study, or clients in a given design project.

- One participant had an expert mindset (Taller [Workshop] Arq. Elio Martínez Joffre): “he [the architect] brings the expertise ... ,” wrote one respondent to the questionnaire; the remainder of respondents did not consider themselves to be the only expert among the pool of participants. The Architecture Office of Martínez Joffre has completed over twenty years-worth of Community Design projects in Puerto Rico.

- All participants developed their projects using the User-Centered Design framework, although they may not have been aware of it as they were using it or defined their projects as such. User-Centered Design approaches operationalize “a design process that focuses on [meeting] user needs and requirements.” [7]

- The client-sponsored project by Rubberband Design Studio was the only one that operated a contextual inquiry and used cultural probes as part of its methodology.

- Six participants incorporated design-led research[i] principles: (Taller de Arquitectura y Urbanismo [Architecture and Urbanism Studio] de Edwin Quiles, Taller de Planificación Social [Social Planning Studio], Proyecto ENLACE [The Link Project], Taller Creando Sin Encargos [Creating Without Commissions Studio], La Maraña [The Tangle], and Oficina de Alianzas [Municipality of San Juan’s Alliances] with its Participatory Budgeting Program.

- Two of the projects profiled in the exhibition were design-led research projects that had been operated by the same participant (Rubberband Design Studio).

- Only five of the participants produced written research reports (the two public sector participants and three of the client-sponsored participants: Taller de Planificación Social, Rubberband Design Studio, and Taller [Studio] Arq. Edwin Quiles). Two grassroots organizations are starting to write about their projects and report their findings: La Maraña and Taller Creando Sin Encargos.

The results of the projects represented in “Listening to Their Voices” affect and impact a diverse array of domains. Seven of the participating groups co-created urban projects and design for use in public spaces. (Examples of these include repairing and otherwise “fixing up” recreational facilities, renovating abandoned houses and converting abandoned lots into community parks.) The architectural projects resulted in the creation of low-income housing. One participant, Rubberband Design Studio, strengthened opportunities among cancer patients to plan and operate resiliency strategies by allowing them to engage in storytelling, and co-created nanoscience games for middle-school students and teachers by using design-led research and participatory action research to guide development processes. Four exhibition participants concentrated on developing initiatives that strengthened community cohesion.

The exhibition has made visible the history of community and participatory design in the local context. Design students who were either involved in the development of the projects featured in the exhibition or who have seen it gained an increased understanding of how to use participatory-design methodologies, which are not taught locally in the regular curriculum of their design courses.

The exhibition also fostered a generational exchange among practitioners, though it should be noted that there was some confusion among the general public and some design practitioners about the definitions of Community Design and Participatory Design, and about how they are related to and different from each other. To help exhibition attendees better understand this, a “toolkit” comprised of a set of 14 playing card-sized “tactics cards was designed (it was based on the strategies and tools depicted in Figure 6). It proved to be the most successful outreach application operationalized by the “Listening to Their Voices” organizers, and also proved to be quite popular among both community members and design practitioners. More information about this toolkit is provided in the next section of this piece.

The documentation of the various activities facilitated by the 15 exhibition participants yielded evidence of two systemic problems that tended to affect the development of their projects. These are discussed in the final, reflective section of this piece.

An Analysis of the Participatory and Community Design Processes, Methods and Working Patterns That Were Operationalized by the Participants in “Listening to Their Voices” to Guide the Development of their Projects

Using the limited resources she had available as preparations necessary to facilitate “Listening to Their Voices” evolved, O’Neill sought to increase her understanding of the methods and working patterns employed by the individuals and groups that had produced exhibition content. In particular, she sought to better understand the Participatory Design processes that guided the development of each the 15 featured projects. As a result of this, each set of educational panels included in the exhibition was designed to visually communicate the Community or Participatory Design methods utilized by the individuals or groups that created the projects depicted on them. To support these depictions, a set of illustrated cards were created and shared with exhibition visitors that were designed to help them better understand the various ways that each of the exhibition participants created their projects. This set of cards was designated as “the toolkit.”

Some of the participants that created projects featured in “Listening to Their Voices” were not aware that they had utilized a design method, as they did not think about or conceptualize the work they undertook in those terms. Some, in fact, stated that they worked “intuitively.” When the organizers of the exhibition asked participants to describe the methodologies they engaged in to guide the evolution of their projects in a questionnaire, they became aware that some of them had difficulty fulfilling this request. In this context, many of them confused their understanding of “methodology” — the system of methods they used to guide their actions — with what they described as the visions, missions, and objectives of their respective projects. A similar problem occurred when many participants were asked to define their preferred tactic (i.e., tool; see Figure 6) in the questionnaire, they confused tactics with strategies. This problem prompted O'Neill to include a category of strategies in the toolkit.

In the participants’ original submissions for inclusion in “Listening to Their Voices,” O’Neill was looking for them to provide three essential pieces of information: a description of their preferred tactic for guiding the development of their project (on the tactics cards, these are referred to as “tools”), how they operationalized it, and who constituted their target audience. As her inquiries were more broadly exploratory, O’Neill did not require that individual participants specify a given tactic when they submitted descriptions of their projects to her. Some of the participants described their strategies, rather than their methodologies, for achieving their project objectives. The authors can only speculate that the manner in which many of the groups operated as they engaged in the processes that informed the development of their projects was not at all rigorously systematic. Additionally, their actions depended on the availability of resources and the operation of organizational structures that were often organic. This tended not to be detrimental to the realization of their respective projects, but it is a concerning factor if others around the world should want to replicate these actions. Without clear documentation of processes and methods, learning could be impaired, and the knowledge that could emerge from facilitating this kind of work could be called into question. (The lack of systemic thinking among Puerto Rican creative practitioners might be a tendency they shared, since it was identified in a previous inquiry that examined the administration of local design schools.[8]) Because of these findings, O’Neill decided that the toolkit would be constituted of two types of cards based on the tools and strategies articulated in Figure 6.

Some of the participants whose projects were documented in “Listening to Their Voices” worked with specific communities and community groups but not necessarily for them. This was true in the sense that their projects were and are community-based, and that they involved and continue to involve members of their given communities in the development of ideas and in encouraging them to provide critical feedback as these evolved, or as they continue to evolve. Other participants did not design for the members of a particular community, but constructed the projects they completed with a high level of involvement of the members of that community. Despite these differences, these projects are participatory, even if different forms of participation are manifested within their respective structural dynamics.

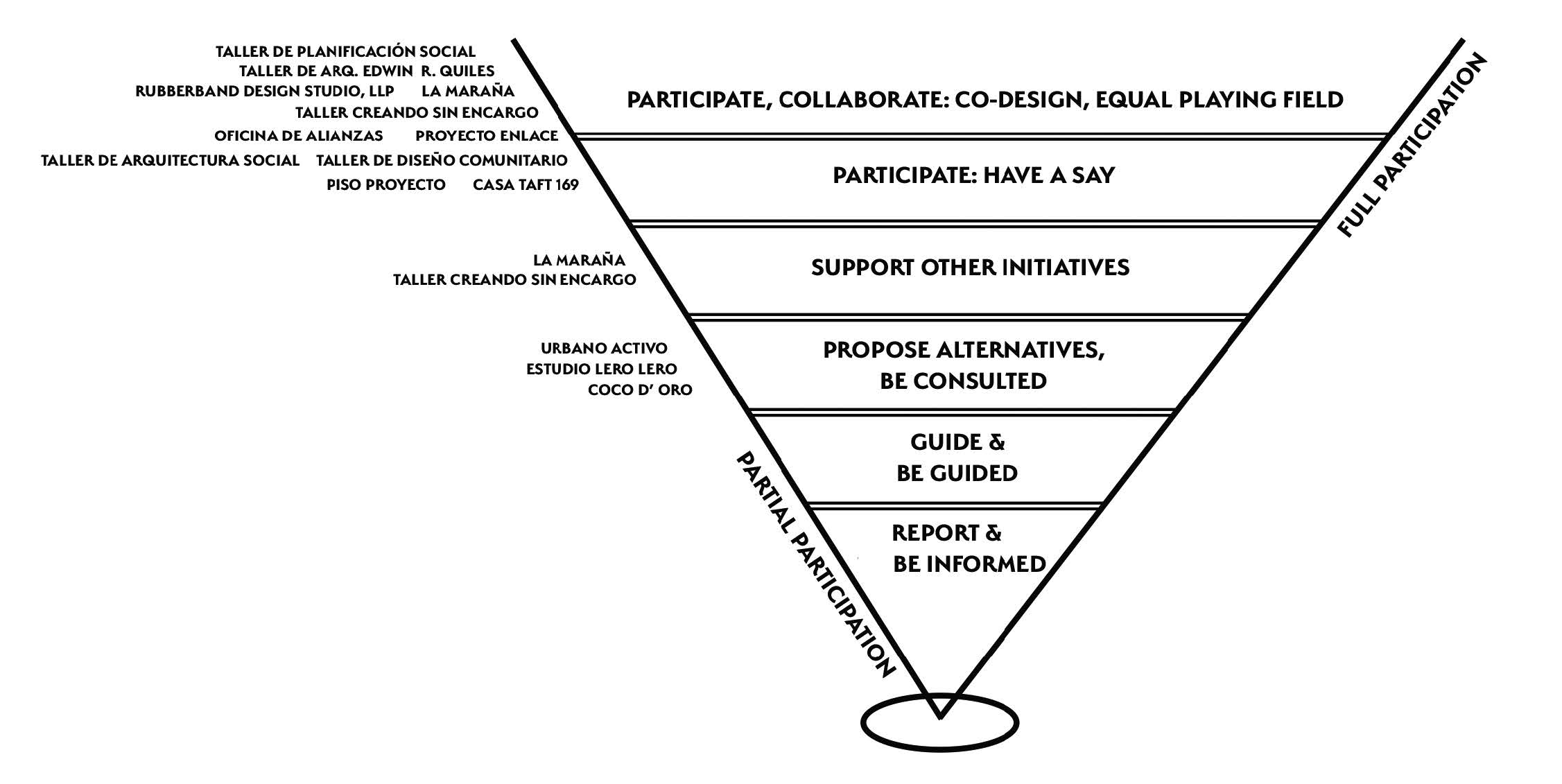

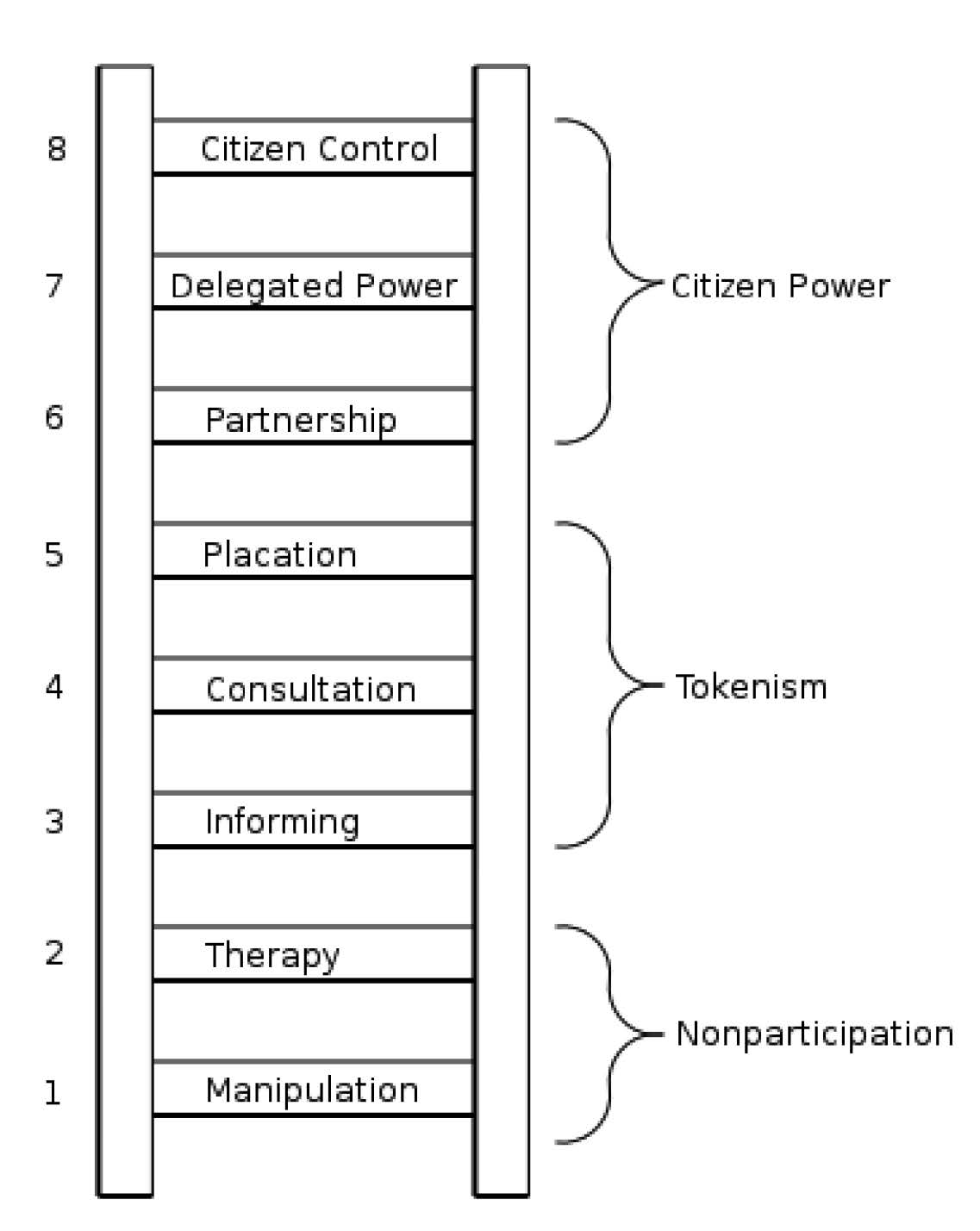

As the authors wanted to accurately quantify the level of participation inherent in each project, they utilized Sherry Arnstein’s model known as the “Ladder of Citizen Participation”[j] to do this (this is depicted in Figure 10). Before explaining how this model accounts for how these projects involved different levels of community participation, the authors would like to clarify that, in order to understand local practices in Puerto Rico, O’Neill worked with co-organizer / co-author Rivera to create their own, local, model of participation for the exhibition of the projects that would eventually constitute “Listening to Their Voices.” Rivera identified six modes of participation among those who submitted projects for inclusion (these are depicted in Figure 7). The authors, like Arnstein, recognized that there are various levels of community participation in the design of each of the projects that were included, but Arnstein’s model includes negative categories, like “Manipulation” and “Tokenism,” that were not reflected in the work submitted by exhibition participants. The authors created several different mo-dels with which to compare the participation levels in the projects that were included in the exhibition, including the one they created (“The Six Modes of Participation”).

For example, designers from the San Juan-based communication design studio Estudio Lero Lero (Lero Lero Studio) presented an idea that they had conceived prior to the initiation of “Listening to Their Voices” to facilitate mural-making by in the Venus Gardens middle school (in San Juan; partially depicted in Figure 8), and out of this idea created and facilitated a workshop during which students and faculty proposed their pictorial ideas (please reference Figure 7, specifically “Level 3: Propose Alternatives: Be Consulted”). According to Daniel Vélez-Climent, the lead designer at Estudio Lero Lero, this workshop allowed those middle school students and teachers whose ideas were incorporated into the mural to feel that aspects of themselves were embodied within it; being involved in the development of this project provided them with a great sense of belonging and of empowerment.

El Taller de Diseño Comunitario (The Community Design Studio; operated by the University of Puerto Rico’s School of Architecture as a means for students there to learn to integrate design theory and practice into various communities across the island) approached the planning and operation of their community-based design initiative differently (Figure 9). They entered into an agreement with members of the Toa Baja community and jointly made a commitment to improving day-to-day living there, and then established guidelines that facilitated the evolution of an inclusive, participatory design process (please reference Figure 7, specifically “Level 5: Participate: Have a Say”). Although Taller de Diseño Comunitario did not establish a collaborative-design methodology, their consultation with residents as the project evolved helped give the people who were involved in it a sense of belonging to a community improvement initiative in which they were essential stakeholders.

In the terms described in the Arnstein model, both Estudio Lero Lero and Taller de Diseño Comunitario, engaged in levels of community participation that occupy the middle portions of the ladder: “Consultation” and “Partnership” (Figure 10). If the design processes that were operationalized to guide the development of these projects entailed only community consultation, this implies that the participation of the citizen stakeholders involved in these projects would not have achieved a level of involvement that satisfies the criteria to attain any of the ladder rung positions in the “Citizen Power” portion of the ladder. This is because consultation should almost always be combined with other forms of participation, including but not limited to co-creation, co-decision and co-building (which metaphorically align with the “Citizen Power” portion of the ladder). Using the authors’ model of the Six Modes of Participation (Figure 7), Taller de Diseño Comunitario facilitated a higher level of user participation as their projects evolved than did Estudio Lero Lero. In other cases, participants such as Rubberband, La Maraña, Taller Creando Sin Encargos, Taller de Arquitectura y Urbanismo de Edwin Quiles, and Taller de Planificación Social employed participation models as a group, in line with both the authors’ model (Figure 7, specifically Level 6: “Participate, Collaborate: Co-Design, Equal Playing Field”) and the “Citizen Power” portion of Arnstein’s ladder.

A third model for gauging and analyzing levels of participation among groups of users or citizens involved in public policy decision-making is that of sociologist Rikki Dean (Figure 11). [9] The Municipality of San Juan’s Alliances Office practices what Dean calls “participation as collective decision-making.” The citizen-participation instrument they have adopted, The Delegates Committee, discusses and negotiates the decisions involved in developing projects to be carried out with a “Participatory Budget.” This term describes a process that allows community members from a given area not only collaborate in the design for their community, but also allows them to gain experience of having to deal with the constraints imposed by a government budget and set budget priorities through a democratic process of voting (Figure 12).

The exhibition project developed and presented by Proyecto ENLACE (the Link Project) practiced, again citing Dean, “participation as knowledge transfer.” This involves creating channels of communication that can be used by residents of the communities surrounding the trash-strewn, mosquito infested Martín Peña Channel in San Juan so that they can help in making decisions and inform or lobby political leaders. These are government-sponsored projects, and consequently Dean’s model is more pertinent in the situations that Proyecto ENLACE and the Municipality of San Juan’s Alliances Office has attempted to affect, but that was not the case with the other “Listening to Their Voices” exhibition participants.

Documenting the Strategies and Tools Used by “Listening to Their Voices” Exhibitors to Facilitate Their Projects: Using the Toolkit to Guide a Hands-On Approach

As was described earlier in this piece, the “toolkit” that was developed by the co-organizers and co-authors of this exhibition to help attendees better understand Community and Participatory Design practices contained Tools and Strategies cards based on the categorical information articulated in Figure 6. The “Listening to Their Voices” participant La Maraña (The Tangle) used “participatory construction” as a strategy to guide the development of their project, and the participant Piso Proyecto (Project Floor) used the physical presence of the bodies of passing people as a way to help them to think about their body as a tool in the context of an urban environment. Exploration was the exhibition participants’ preferred tool (see below), and creating motivation was operationalized as both a tool and a strategy. The following list articulates the patterns of use regarding the exhibition participants’ preferred tools (8) and strategies (5):

- Exploration (five tools) — A visual timeline that involves the creation of neighborhood maps, storytelling, making collective photo trips around a specific neighborhood, creating and conversing about portable architectural models, and using input from committees of community representatives.

- Visualization (one tool) — A neighborhood map configured like a jigsaw puzzle on which members of the community could record their requests.

- Feedback (one tool) — Using the body as a physical prop to inform understandings about interactions between people and people and built and natural forms in public urban spaces.

- Motivation (one tool) — A means to reach a collaborative agreement.

- Sharing knowledge (two strategies) — An open-source approach to event-making and sharing a story in local and international forums.

- Teaching others (two strategies) — A workshop themed around construction and the creation of community gardens for public spaces, as well as a workshop that guided the creation of a mural that depicted community issues.

- Motivation (one strategy) — A means to identify a local practice as a collective event (based on oral history).

The tactic of using visual approaches, like jigsaw maps and photography, among others, seemed to be the common pattern among the exhibition’s participants. Four of the participants in “Listening to Their Voices” used images as part of the toolkits they employed to work with various community members (these were Taller Creando Sin Encargos [Creating Without Commissions Studio], Taller de Planificación Social [Social Planning Studio], Rubberband Design Studio, and Taller de Arquitectura y Urbanismo de Edwin Quiles [Architecture and Urbanism Studio of Edwin Quiles]). Rubberband Design Studio used illustrated concept cards as a means to help their clients and users tell stories about their experiences living and working in particular situations. Taller de Planificación Social used a map constructed out of pieces similar to a jigsaw puzzle. Only one participant, Proyecto ENLACE, used an interactive architectural model as its main tool, although the university students involved in Taller de Diseño Colaborativo and the architects of the Oficina de Alianzas have also used this tool (among others). Using a portable, physical architectural model, potential users can get a better idea of the scale of the project and how each design decision has had an impact on the context within which the project transpired or was placed. Taller Creando Sin Encargos and Taller de Arquitectura y Urbanismo de Edwin Quiles used photography as an analytical tool, so members of the community could explore new uses for public spaces in their neighborhood (Fig. 11).

These approaches are commonly used in design and architectural practice. Not so common, and therefore more unexpected, was a tactic used by some exhibition “Listening to Their Voices” participants: “acting out” as an exploratory approach or to envision future or possible societal interactions (this occurred during the evolution of projects undertaken by the organizations Piso Proyecto [Floor Project] and Urbano Activo [Active Urban]). These approaches may have been intuitively created by their respective project organizers, but each relied on the utilization of immersive practices to exploit knowledge gained from the documentation of both user experiences and the emotional significance regarding human interaction in and around a specific public space. Piso Proyecto used a portable wooden dais to facilitate an on-site movement-based performance of the history of specific localities in different places in different cities (for example, forced expropriation in San Juan), and then invited passerby to interact the performers to address community issues. Urbano Activo (Figure 14) has facilitated impromptu, open-call community breakfasts in public spaces to involve community members in interactions that help them begin to rethink how the spaces around them and that they inhabit might be used, a strategy that has since been taken up by other organizations.

Final Reflections: Tricky Questions and a New Challenge

In this paper, the authors have identified the participatory methodologies, patterns of use, tactics (tools), and strategies that have been used to guide various types of design and urban projects in Puerto Rico. The primary insights that the authors have gained about these societal-value projects are that many evolved intuitively, and that methodologies were created and are developed further as they emerged from practitioners’ tacit knowledge as particular projects evolved. To what extent these processes could be replicated is a tricky question. An important finding of developing and operating “Listening to Their Voices,” as a Practice-led Research [k] initiative, reveals a two-pronged challenge. The first is that the majority of the participants in this exhibition do not (and did not) document their work on their respective projects effectively. The second is that very few of them have utilized established internal and external verification procedures to qualify the relative validity of their undertakings, which often involves publishing accounts of their design processes and their outcomes in scholarly venues like Dialectic. Addressing both aspects of this challenge becomes inherently complex given the nature of the projects themselves and the lack of resources available to the project organizers and facilitators to undertake these processes effectively.

The importance of documenting and publishing (preferably in rigorously vetted, internationally distributed venues) was and is not widely recognized among the exhibition participants. Projects that have historical precedents, like that developed and operated by the Taller de Diseño Comunitario (Community Design Studio) at the University of Puerto Rico’s School of Architecture, are often not documented in ways that could positively affect public awareness or action. A previous inquiry determined that at present, local design and architecture schools do not require educators in their employ to publish or to be involved in design research. [10] Indeed, there has been a general lack of documentation of industrial-, graphic-design and community-design projects that have been operationalized by or that have involved contributions from Puerto Rican design educators or their students. There are several reasons for this state of affairs:

- a lack of financial and infrastructure support from both the Puerto Rican and American governments and from the educational and professional institutions that are situated on the island to support the instantiation and the maintenance of design process-based and designer archives;

- the transitory / migratory nature of those who practice the design profession, meaning that designers often move from one studio or consulting firm to another, and, as a result of this process, documents, designs, and documentation files are lost or left behind and often later destroyed;

- designers often work on a freelance basis, and do not themselves have the space, time, staff, and — especially — the training and awareness necessary to maintain their archives;

- the lack of almost any academic requirements that encourage or require design students in university programs to document or maintain a history of the decision-making processes that have guided the evolution of their respective projects, coupled with the lack of any training regarding the maintenance of such archival materials (students produce design projects, but are not required to document them or produce essays that describe their design and implementation processes).

This last gap in training means that professionals emerge from design schools being largely unaware of the need for (and) importance of documenting their projects and processes. This may perhaps be the most telling reason of all to explain the “documentation gap.”

Regarding the failure of design academia to foment a culture of documentation and research through design,[11][12] Dr. Luz María Rodríguez, an independent design research consultant and architectural historian, says,

“There is a difference between doing design and generating knowledge in design [emphasis by the authors of this piece]. In Puerto Rico, the emphasis tends to be on the product, not the process, precisely because it is not the process and, within that, the research, that is rewarded in design courses ... . [socio-cultural anthropologist Arjan Appadurai] told me [Dr. Rodríguez] that there is a great deal of talk about research in universities; students are required to “do” research (now even at the undergraduate level), but they aren’t taught how. Clearly, this has consequences later, in the way designers approach, frame, execute and assess the effectiveness of their work. For example, there are few designers in Puerto Rico who consciously subscribe to methodologies associated with Design Thinking or Human-Centered Design, which do not [merely] establish methodological maps for the execution of projects . . . the stages they prescribe are, or imply, models or strategies of documentation. . .. When [designers] do not begin with research as a referent, they limit or skip steps, mainly the steps of dissemination and reuse of their findings. [Cross , 2007][13] There is a difference between exploration and research. As the RIBA [Royal Institute of British Architects] article titled “What is Architectural Research?” [ Till, 2004][14] argued, “... whilst architects [designers] may believe that knowledge is there in the building to be appropriated by critics, users or other architects, they [the buildings or the products] very rarely explicitly communicate the knowledge.” That requires an interpreter because architects and designers seldom communicate the knowledge contained in their designs in an explicit way. I think this applies to Puerto Rico, too. [15]

The authors want to clarify that this is not the case with Puerto Rican social and community psychologists, who have a prolific history of research, publishing, and systematically documenting their participatory projects. (It should be noted that they generally have university support to formulate and engage in this research.)

What is described here is not only true of Puerto Rico, but has also been discussed in the AIGA white paper “The Designer of 2025.” AIGA (the American Institute of Graphic Arts) recognized that “there is a shift from asymmetrical, one-directional relationships between users and information to communication strategies built on models of conversation, participation, and community.” [16] AIGA and other international design organizations have documented the paradigm changes in design practice that have affected ways of doing research that informs ideation and front-end design results.

Are other creative practitioners learning from the success of these Puerto Rican projects? Are other Puerto Rican practitioners learning new, or at least improved, ways to facilitate user extrapolations and collaborations? These are even harder questions to answer. There are two groups currently making a point of encouraging others to replicate their work: Casa Taft 169 and Urbano Activo. They have reported that other Puerto Rican organizations are beginning to replicate their models — community and artist organizations in the case of Casa Taft 169 and mostly community organizations in that of Urbano Activo. Also, Rubberband Studios’s cancer project methodology and resources are available online for other groups to replicate, but there is no evidence that (as of this writing in the spring of 2018) that this has occurred. Lastly, Taller de Diseño Comunitario (The Community Design Studio at the University of Puerto Rico’s School of Architecture) and Taller de Diseño Colaborativo (The Collaborative Design Studio), which is part of the initiative Taller Creando Sin Encargos (Creating Without Commissions Studio) operated by the Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico), state that — as an essential aspect of their respective missions — students enrolled in their design programs will learn to design with communities.

Practitioners of projects that have been designed to address difficult problems involving the historical deterioration of Puerto Rico’s cities and the complex, societal interrelationships that exist among Puerto Ricans need to incorporate the components of verification, reflection, and documentation into their approaches and methods. There is no question as to the contributions that the exhibition “Listening to Their Voices” participants are making in these vital areas (as depicted in Figures 15 and 16). But what is not documented, sadly, does not exist, because it is invisible, not only locally but also to the international design communities. The primary challenge lies in preventing these contributions from becoming isolated, which would severely limit the scope of change they could affect in and around other communities in the world struggling to address serious natural, financial and public policy challenges. The essential nature of these type of Participatory and Community Design projects provide robust seeds from which positive social, economic and cultural transformation can grow. In these ways, the exhibition “Listening to Their Voices” has been an effective means to help designers and their citizen collaborators better comprehend and create new knowledge of and about collaborative design methodologies as they affect and are affected by current design practices and educational approaches.

References

- ———— . Puerto Rico Unemployment Rate. Available at http://www.tradingeconomics.com/puerto-rico/unemployment-rate (Accessed July 12, 2016).

- American Institute of Graphic Arts. “AIGA Designer 2025: Why design education should pay attention to trends.” Design Educators Community (2017). Online. Available at: https://educators.aiga.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/DESIGNER-2025-SUMMARY.pdf (Accessed November 21, 2017).

- Arnstein, S. R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. JAIP, 35.4, 1969.

- Cotto Morales, L. “Experiencias en diseño participativo: los múltiples significados de la participación. Un principio de pedagogía urbana.” In Escuchando las voces (exhibition catalog, 2016): pgs. 23–25.

- Cross, N. “From a Design Science to a Design Discipline: Understanding Designerly Ways of Knowing and Thinking,” Design Research Now: Essays and Selected Projects (Board of International Research in Design), edited by R. Michel, Basel, SUI: Birkhäuser, 2007, pgs. 41–54.

- De Carlo, G. “Architecture’s Public.” In Architecture and Participation, edited by P. B. Jones, D. Petrescu & J. Till, London: Taylor & Francis, 2005 (originally published as “Il pubblico dell’architettura,” Parametro, No. 5, 1971).

- Dean, R. “Policy Briefing: There is more than one way to involve the public in policy decisions.” Discover Society, 1 June 2016. Online. Available at: http://discoversociety.org/2016/06/01/policy-briefing-there-is-more-than-one-way-to-involve-the-public-in-policy-decisions/ (Accessed August 19, 2017).

- Faccio, B. “Left Behind: Poverty’s Toll on the Children of Puerto Rico.” Child Trends, 28 March 2016. Online. Available at http://www.childtrends.org/left-behind-povertys-toll-on-the-children-of-puerto-rico/ (Accessed August 18, 2017).

- Fernández, S, & Bonsiepe, G. Historia del diseño en América Latina y el Caribe: Industrialización y comunicación visual para la autonomía. São Paulo: Blücher, 2008.

- Frayling, C. (1993). Research in art and design. Royal College of Art Research Papers series, 1(1).

- Gibson, M.R. & Owens, K.M. “Making meaning happen between ‘us’ and ‘them’: strategies for bridging gaps in understanding between researchers who possess design knowledge and those working in disciplines outside design.” In The Routledge Companion to Design Research, edited by J. Yee and P. Rodgers, pgs. 386–399. Routledge, NY, NY, USA: 2015.

- Guerrero Barón, J. Colombia y América Latina después del fin de la historia, Volumen 1. Tunja, Boyacá, Colombia: Editorial de la Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC), 1997.

- Illich, I. Tools for Conviviality. London / NY: Marion Boyers, 1973. Online. Available at http://www.preservenet.com/theory/Illich/IllichTools.html (Accessed July 13, 2016).

- Jones, P. B., Petrescu, D., and Till, J. Architecture and Patricipation. London: Taylor & Francis, 2005.

- Marvel, L. Listen to What They Say: Planning and Community Development in Puerto Rico. Rio Piedras: UPR Press, 2008.

- ———— . E-mail to Maria de Mater O’Neill and Omayra Rivera, August 21, 2016. RE: adjunto paper de co-creation.

- O’Neill, M. M. “Pesquisa sobre la gestión empresarial de Maruja Fuentes Viguié,” iPolimorfo, San Juan: Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico, 2017, pp. 58–65.

- ———— . “Views and Reflections on Design Education: Local Voices from Puerto Rico.” Foroalfa (2015). Online. Available at http://foroalfa.org/articulos/views-and-reflections-on-design-education-local-voices-from-puerto-rico (Accessed July 24, 2016)

- Quiles, E. E-mail to María de Mater O’Neill, July 14, 2016. RE: Fwd: coteja esta definición Personal.

- Rigau, J. “MoMA y EMA.” El Nuevo Día (newspaper), June 2, 2015, Editorial. Online. Available at: http://www.elnuevodia.com/opinion/columnas/momayema-columna-2054646/ (Accessed July 24, 2016).

- ———— . E-mail to María de Mater O’Neill, July 30, 2016. RE: Consulta Personal.

- Rivera Crespo, O. Procesos de Participación: Proyectar, Construir y Habitar la Vivienda Contemporánea. Barcelona: Editorial Académica Española, 2011.

- Sanoff, H. Programación y participación en el diseño arquitectónico / Programming and Participation in Architectural Design (bilingual edition). Arquitectonics: Mind, Land & Society series. Barcelona: Ediciones Universidad Politécnica de Catalunya, 2006.

- Santos Lozada, A. & Velázquez Estrada, A. “The Population Decline of Puerto Rico: An Application of Prospective Trends in Cohort-component Projections.” Instituto de Estadísticas de Puerto Rico, Série de Documentos de Trabajo, 2015-1 (October 2015). Online. Available at http://www.estadisticas.pr/iepr/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=EnVmZKo5nSo%3D (accessed July 13, 2017.)

- Till, J. “The Negotiation of Hope.” In Architecture and Participation, edited by P. B. Jones, D. Petrescu & J. Till, London: Taylor & Francis, 2005.

- United States Census Bureau. Income in Puerto Rico Holds Steady After Recession. January 30, 2014. Online. Available at: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2014/cb14-17.html (accessed: July 12, 2016).

- Zimmerman, J., Forlizzi, J., & Evenson, S. “Research through design as a method for interaction design research in HCI,” in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 28 April–03 May, 2007, San Jose, CA, USA: pgs. 493–502.

- Zimmerman, J., Stolterman, E., & Forlizzi, J. “An analysis and critique of Research through Design: towards a formalization of a research approach,” in Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, 16–20 August, 2010, Aarhus, Denmark, 2010: pgs. 310–319.

Biographies

Dr. María de Mater O’Neill is the Head Researcher and Creative Director of Rubberband Design Studio, LLP and a Fulbright Specialist Roster candidate. She is the recipient of a Round Four of the Presidential Design's Federal Design Achievement Award for Catalog Design (United States), and II Iberoamerican Design Biennal's BID Prize for Exhibition Design (Spain). Her practice-based doctoral research initiative “Developing Methods of Resilience for Design Practice” is a design model intended to improve real-time resilience thinking for designers working under a variety of types of economic and socio-cultural stressors. She is member of the Peer Review Collegium of She Ji — The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, published by Elsevier in collaboration with Tongji University and Tongji University Press, China, and the Revista Tecnología & Diseño, published by Departamento de Procesos y Técnicas de Realización de la UAM-A (México).

Dr. Omayra Rivera Crespo, Ph.D. earned her doctorate from the School of Architecture La Salle in Barcelona. She holds a Master’s degree in Architecture from Arizona State University and a Bachelor’s degree in Environmental Design from the University of Puerto Rico. She has cultivated experience as an architect and design educator in Boston, Barcelona and Puerto Rico.

She is the author of Procesos de Participación: Proyectar, Construir y Habitar la Vivienda Contemporánea (Participation Processes: Project, Build and Live in Contemporary Housing, Editorial Académica Española, 2011), was member of the editorial committee of the magazine Entorno and is member of the editorial committee of the magazine Polimorfo. She co-founded the collective “Taller Creando Sin Encargos,” (Creating Without Commissions Studio), founded the Collaborative Design Studio in Beta Local and the Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and has worked as Project and Citizen Participation Manager in the Municipality of San Juan. She has also been the Community Art Projects Coordinator at the Puerto Rico Museum of Contemporary Art.

Notes

- a

Convivial” in this context of use conveys the sense of “living-together,” or the definition given “conviviality” by Ivan Illich: “I choose the term ‘conviviality’ to designate the opposite of industrial productivity. I intend it to mean autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment; and this in contrast with the conditioned response of persons to the demands made upon them by others, and by a man-made environment. I consider conviviality to be individual freedom realized in personal interdependence and, as such, an intrinsic ethical value.” (Ilich, I. Tools for Conviviality. London, UK/New York, NY, USA: 1973: Marian Boyars, Publishers. Excerpt quoted from Andrea Gibbons, 20 November 2015, Online. Available at: http://writingcities.com/2015/11/20/ivan-illichs-tr-conviviality/ (Accessed February 1, 2018).)

- b

Co-creation” in this context is the act of creating or designing with the user by, among other things, exchanging knowledge and experiences, refining (“tweaking”) goals, and incorporating perhaps overlooked or somewhat undervalued elements.

- c

The authors discuss this scarcity of documentation on pgs. 151-157.

- d

Refer to the Project Website and Facebook: escuchandolasvocesblog.wordpress.com, @escuchandolasvoces

- e

The architects who eventually formed Team 10 had been attending meetings of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (C.I.A.M.) for several years when they began to come together as a group that shared ideas about how modern cities should be planned and designed at the 9th congress in 1953. This small group of (mostly) younger architects made their group “official” (at the 10th C.I.A.M. Congress in 1956). They sought to build a “working-together-technique” (referring to working with the people living in urban environs who would eventually be affected by the decisions of architects) to address many of the issues they felt would affect these populations as cities were modernized. They were primarily concerned with designing and reforming cities so that they would become more effectively organized and efficiently functional and livable for their inhabitants.

- f

The “Law to Create the Cantera Peninsula Comprehensive Development Company.”

- g

The “Law to create the Caño Martin Peña Comprehensive Development Company.”

- h

The strategically desirable location of this area in the context of the real estate market in and around San Juan makes the action of buying houses and the land they occupy and then selling the two as a combined property much more of an expensive endeavor for would-be speculators seeking to artificially inflate prices in this market.

- i

In design-led research, new knowledge is constructed by engaging in the design process as interactions with a given community or group of users (or an individual) evolve.

- j

Arnstein, S. R. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Planning Association, 35.4, 1969, pgs. 216–224. Sherry Arnstein was an American public policy analyst and consultant who worked for and advised the U.S. Department of Housing, Education and Welfare (HUD) from 1964 until 1985. The ideas that she articulated in this paper were and still are referenced as metaphors that can be used to increase understanding about whether or not citizen involvement or participation in a given community initiative is honestly sought and effectively incorporated into its development. When those in power merely create the illusion of involving citizens and other key stakeholders in decision-making processes, only the “bottom rungs” of the ladder—“Manipulation” and “Therapy” (as depicted in Figure 10)—are utilized.

- k

Practice-led-research aims to create new knowledge about practice; in this case, the practice of design.

Gibson, M.R. & Owens, K.M. “Making meaning happen between ‘us’ and ‘them’: strategies for bridging gaps in understanding between researchers who possess design knowledge and those working in disciplines outside design.” In The Routledge Companion to Design Research, edited by J. Yee and P. Rodgers, pgs. 386–399. Routledge, NY, NY, USA: 2015.

Santos Lozada, A., and Estrada, A.V. “The Population Decline of Puerto Rico: An Application of Prospective Trends in Cohort-Component Projections.” Instituto de Estadísticas de Puerto Rico, Série de Documentos de Trabajo, 2015-1 (October 2015): p. 10. Online. Available at: http://www.estadisticas.gobierno.pr/iepr/Sobrenosotros/Seriededocumentosdeinvestigaci%C3%B3n.aspx (Accessed January 31, 2018).

Faccio, B. “Left Behind: Poverty’s Toll on the Children of Puerto Rico.” Child Trends [blog], 28 March, 2016. Online. Available at: https://www.childtrends.org/left-behind-povertys-toll-on-the-children-of-puerto-rico/ (Accessed January 28, 2018).

Arnstein, S. R. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” JAIP, 35.4 (1969): pgs. 216–224; De Carlo, G. “Architecture’s Public.” In Architecture and Participation, edited by P. B. Jones, D. Petrescu & J. Till, London, UK: Taylor & Francis, 2005 (originally published as “Il pubblico dell’architettura,” Parametro, No. 5, 1971); Sanoff, H. Programación y participación en el diseño arquitectónico / Programming and Participation in Architectural Design (bilingual edition). Arquitectonics: Mind, Land & Society series. Barcelona, ES: Ediciones Universidad Politécnica de Catalunya, 2006; Marvel, L. Listen to What They Say: Planning and Community Development in Puerto Rico. Rio Piedras, PR, USA: UPR Press, 2008; Till, J. “The Negotiation of Hope.” In Architecture and Participation, edited by P. B. Jones, D. Petrescu & J. Till, London, UK: Taylor & Francis, 2005; Dean, R. “Policy Briefing: There is more than one way to involve the public in policy decisions.” Discover Society, 33 (2016).

Marvel, L. E-mail to M. M. O’Neill & O. Rivera Crespo, August 21, 2016. Re: adjunto paper de co-creation.

Feliciano Ramos, H. “Transformación de una sociedad dependiente: 1940–1994.” In Colombia y América Latina después del fin de la historia, Volumen 1, ed. J. Guerrero Barón. Tunja, Boyacá, p. 180. Colombia: Editorial de la Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC), 1997.

Anon. “What is User Centered Design?,” Interaction Design Foundation, 11 October 2013. Online. Available at: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/user-centered-design/ (Accessed 18 March 2018).

O’Neill, M. M. “Views and Reflections on Design Education: Local Voices from Puerto Rico.” Foroalfa (2015). Online. Available at: http://foroalfa.org/articulos/views-and-reflections-on-design-education-local-voices-from-puerto-rico (Accessed August 18, 2017).

Dean, R. “Policy Briefing: There is more than one way to involve the public in policy decisions.” Discover Society, 1 June 2016. Online. Available at: https://discoversociety.org/category/issue-33/ (Accessed 17 August 2017).

O’Neill, M. M. “Views and Reflections on Design Education: Local Voices from Puerto Rico.” Foroalfa (2015). Online. Available at: http://foroalfa.org/articulos/views-and-reflections-on-design-education-local-voices-from-puerto-rico (Accessed August 18, 2017).

Frayling, C. (1993). Research in art and design. Royal College of Art Research Papers series, London, UK. Online. Available at: http://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/384/3/frayling_research_in_art_and_design_1993.pdf (Accessed 30 March, 2018).

Zimmerman, J., Stolterman, E., & Forlizzi, J. “An analysis and critique of Research through Design: towards a formalization of a research approach,” in Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 16–20 August, 2010, Aarhus, Denmark, 2010: pgs. 310–319.

Cross, N. “From a Design Science to a Design Discipline: Understanding Designerly Ways of Knowing and Thinking,” Design Research Now: Essays and Selected Projects (Board of International Research in Design), edited by R. Michel, Basel, SUI: Birkhäuser, 2007, pgs. 41–54.

Till, J. Royal Institute of British Architects' Research and Development Committee, “Memorandum: What is Architectural Research?” Architectural Research: Three Myths and One Model (London, UK: RIBA, 2007) Online. Available at: https://jeremytill.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/post/attachment/34/2007_Three_Myths_and_One_Model.pdf (Accessed 21 November 2017).

Rodríguez, L. M. E-mail to M. M. O’Neill, August 19, 2017. “RE: artículo.”

American Institute of Graphic Arts. “AIGA Designer 2025: Why design education should pay attention to trends.” Design Educators Community (2017). Online. Available at: https://educators.aiga.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/DESIGNER-2025-SUMMARY.pdf (Accessed 21 November 2017).