Discourses on the Methods: Investigating the Narratives of Design Education in France

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This paper proposes a shift in the mainstream affirmation that constitutes design’s disciplinary identity. Specifically, it makes the case that design should instead be thought of and taught as a cultural discourse that aims to establish and sustain an inclusive community of practices and practitioners. This shift allows design to be practiced and taught in ways that can get beyond narrowly informed, objective descriptions or processes and their outcomes.

Our piece examines the French context for design education as it relates to practice because 1) it has rarely been exposed to a foreign audience, and 2) because of its value as a means to address a more universally framed reflection of and about design’s disciplinary status. We argue that this choice of context is relevant in two principal respects: on the one hand, the fundamental understanding of “design” and “design practice” in French design history is strewn with controversies about its epistemological definition and legacy. On the other hand, as the teaching of design in France was until very recently classified as a vocational type of education, it was (and, to a degree, still is) framed by a vast regulatory literature that is supposed to tightly define the role of designers and design practice.

Governmentally approved literature has been written to guide how graphic design is taught in France so that aspiring French designers acquire and master the skills, value sets and general bases of knowledge necessary to enter the profession. This literature also stipulates specific guidelines that frame her training. The existencliterallye of this official literature has allowed us to examine and highlight how institutionally mandated language can convey vague, inconsistent and sometimes contradictory definitions and representations. In a second step of our examination, we share the results of a field study we conducted with students to see how effectively they interpreted the instructions mandated by this literature. In particular, we asked them to consider whether their approaches to engaging in the practice of design are strictly guided by the officially sanctioned and approved method(s) or not, and to what extent. We reached the conclusion that many discourses currently circulating which assume the existence of stable, operational and fundamental methods for guiding the teaching and practice of design are too limiting. We found that design as a discipline is less aptly described as an objective approach for engaging in a practice and better described as a shared array of diverse discourses that allow the design community to develop, relate and exchange ideas that increase knowledge and understanding.

Introduction

In France, discourses and practices within the educational community are centered on a “method(olog)ical” approach to the design project as a set of mandatory skills to be mastered in order to meet the qualifications necessary to become a professional designer. This paper argues that these educational expectations also perform as a cultural and symbolic apparatus. While these types of “methodologies” are praised by many who teach and administrate within educational institutions—through the abundant “grey literature”[a] describing and guiding higher design education—they might paradoxically act as an operative black box, nurturing a constructed narrative engaged in the (re)production of a cultural common ground. We are trying to highlight how so-called design methodologies may constitute a performative[1] and circulating utterance that tends to circumscribe the design community (practitioners, commissioners, students, teachers, researchers). By doing this, the design community can relate, reflect and actualize through this discursive and narrative apparatus.

This piece seeks to document teaching specificities in France to highlight these types of narratives of and about design in design education. We propose “discourses on the methods” as an umbrella-term for all the discourses describing design practice as a methodical, project-driven activity, as in:

- scientific literature (as approached by Findeli, Hatchuel, Cross, Koskinen, Vial, etc.),[2]

- literature widely acknowledged as being milestones for design history and historiography (Morris, Moholy-Nagy, Ruskin, etc.),[3]

- or even as it emerges from a reflective design practice (Mendini (1972) as quoted by C. Geel, Munari, Branzi, Sottsass Jr., Rams).[4]

Following this set of definitions and statements that have been widely acknowledged throughout the design community, it appears that the “project” is understood as the spine, or essential core, of design practice. According to Nigel Cross,[5] design practice is constructivist, solution-oriented and relies on following a method rigorously,[6] for example, the iterative design process, i.e. a cyclic process of prototyping, testing, analyzing, and refining a work in progress. Nevertheless, Cross remains reserved about the designer’s ability to develop a methodology, that is, to make design methods a reliable and replicable model:

“Sir Frederick Bartlett pointed out, “The experimenter must be able to use specific methods rigorously, but [s]he need not be in the least concerned with methodology as a body of general principles. Outstanding ‘methodologists’ have not themselves usually been successful experimenters” (Bartlett, 1958). If ‘designer’ is substituted for ‘experimenter,’ this observation also holds true in the context of design.”[7]

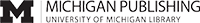

As design began its pursuit of its academic turn in the mid-1960s, we can see how design practice and design teaching started to be aimed at strengthening design’s scientific and academic legitimacy, especially in France, where the current reform of higher education linked to the Bologna process now obliges institutions to offer doctoral programs in design. The question of methods, and even more so of methodology—that is to say a modeling abstractization of methods—is therefore central, as it is entirely immersed in the process of scientific experimentation, validation and replication. Here we seek to highlight how methods within the design project itself might act as an operative black box, i.e. an operating system within which only inputs and outputs are clearly identified, and where internal workings remain opaque,[8] while “discourses on the methods” might nurture design’s own “regime of truth”[9] (see Figure 1).

Part 1: Elements for an Investigation of the French Model for Design Education

Research Inputs & Methodology

We had an opportunity to facilitate our research during two workshops conducted in Paris in January 2015 and November 2015 with a class of postgraduate design students. These workshops were part of their Design Research seminar run by Tiphaine Kazi-Tani, a design teacher and researcher working in France, and were intended to introduce this group of students to project-grounded and practice-led research. As these workshops were structured to facilitate the investigation of how the context (either professional practice or practice-based research) could possibly rearrange design methods, it seemed appropriate to attempt to identify how the students perceived, described and tested these methods. This guided Frédéric Valentin (a design teacher and PhD. candidate) to conduct a series of semi-structured group interviews with the students during the first workshop, in January, to document the nature of their experiences and their thoughts about design methods; during the November workshop, he also led interviews (co-conducted with Justė Pečiulytė, a fellow PhD. candidate) with four guest researchers,b and distributed anonymous surveys to the students.

During their terminal year of study, postgraduate students in France are expected to produce an individually guided, practice-based research project or assignment. This fact guided the structure of these workshops, as they were premised on the attempts of the teacher who facilitated them to help these groups of postgraduate students understand how and why tools and skills from the project-driven design practice might or should be repurposed to guide efforts in and around the discipline of design-research, an approach that could prove to be fertile in light of their having to satisfy the parameters of their final-year assignment. This specific orientation was triggered by their thesis supervisor’s previous observations about key aspects of their understandings of how design research approaches and methods might (or might not) affect and be affected by approaches and methods rooted in professional design practice:

- the students had difficulties thinking of practice-based approaches in ways other than those that could be couched within an endeavor to respond to a question with a design-led solution,[10] which was more in line with the expectations of the profession—“these design-led solutions are the ones exposed in glossy magazines (...) or in the downtown design galleries”[11]—than expected from a research approach;

- the need to find relevant and commonly shared input that would allow them to formulate a new set of approaches for interrogating, and, as necessary, reconfiguring their current practices; it was then important to reassure students about the fact that they wouldn’t have to learn dramatically new skills, but instead learn new approaches based on skills they had already mastered, such as creating moodboards, engaging in a creative process and prototyping; also, the teacher assumed that, with “method” supposedly being the core skill of any design curriculum according to the French official educational guidelines, it could be some sort of common skill to build upon considering the heterogeneity of the students (originally selected from various design curricula taught with the École de Condé-Paris).[c]

This assumption itself was nurtured by the Référentiels de Formation et de Certification, or “Training and Certification References and Guidelines.” This body of grey literature is typical of the documents that have been written by French educational policy makers to articulate learning strategies and outcomes throughout the French vocational educational system. These référentiels[d] define sets of educational and testing standards for vocational training, and they provide the guidelines that structure a given higher education curricula as a means to facilitate the acquisition of the specific vocational skills relevant to effectively practicing a given professional discipline.

Although intended for teachers’ use, these official documents are divulged freely, without restriction to access. They describe the following:

- an institutional (i.e., mandated by government-affiliated, educational authorities) vision of vocational education;

- an institutional vision of the scope of subjects to be studied, and bases of knowledge and skill sets that determine a discipline;

- this discipline’s relationships to society and the professional world;

- recommended approaches to understanding the essential nature of the discipline, and to teaching students who wish to study the discipline;

- the suggested structure of training sequences and the recommended program of courses necessary for students to enter the discipline;

- the mandatory, standard skills and bases of knowledge that that students must acquire effectively enough to be tested on by the time they complete a given curriculum;

- the standard framework that must be employed to evaluate the acquisition of these skills and bases of knowledge as ascertained through standardized exercises and tests.

We have used the material articulated within these référentiels, as well as content derived from reports on design education produced by government agencies, to investigate the process of production of an institutional standpoint over design and its education in France. We highlight why, how and when not only the term “methods” but also the idea of design as a step-by-step methodological approach are engaged in the production of a discourse-of-truth affecting design as a professional activity. We then utilize the guidelines provided by governmentally affiliated French educational authorities that 1) currently affect the strategic and tactical delivery of design education, and that 2) shape how individual students’ experience the teaching of design, to test the following hypotheses:

- educational discourses and the narratives that inform and frame them have to describe and outline design as a professional practice; these are also supposed to account for its historiographic identity, and inscribe it in the wider perspective of education as a space within which citizenship can be crafted; while these discourses and narratives are forming an imaginary representation of professional practice, they are also forming a viable social and cultural context for design;

- these narratives establish a performative loop between design education and design practice: the designer is the professional of the creative method because the professional world says so, while if the professional world can claim that the designer is the professional of the creative method, it is because design education is dedicated to train her to be;

- what the various actors of design name “methods” or “methodology” is in fact the discursive and performative core of design’s regime of truth (Figure 1);

- the educational approaches and practices that facilitate project-grounded and practice-led research aim at building, spreading and sharing a disciplinary culture, where design methods constitute an actual set of skills as well as a rhetorical apparatus that allow the design community to self-identify.

Design Education in France: A Brief Exposé

Design education is rather young in France. It took almost over a century to sort out design as a discipline familiar with but different from applied arts, arts & crafts, industrial arts, etc. The terms of its definition and structuring[12] are still at the center of critical discussions among design educators and those who administrate French design education programs, as well as design professionals. We wish to introduce what we feel are the key particularities of these discussions through a brief exposé. As Brigitte Flamand’s report on Design & Crafts education reminds us:

“Thus, from the workshop to industry, the ambition was to train skilled master craftsmen out of the workshops and corporations. Following the same logic, the City of Paris created, in the late 19th century, the first municipal vocational schools, as did the City of Lyon, to properly train young, qualified craftsmen. The arrival of André Malraux [as Minister of Culture, A / N, in 1959] participated in the structural and intellectual separation between art and technique, which precipitated a long-term split between the arts and the professional training in applied arts, industrial arts, and crafts.”[13][14]

Though we do not intend to dwell thoroughly on the history of the development of French arts & crafts and industrial design,[15] we feel it is necessary to point out two essential characteristics of these, as they are pertinent to our reflection.

- Because of its historical link to the classic arts & crafts training, design education has long been integrated to vocational education. From the progressive coordination of design and crafts curricula in the mid 1960s until now, design education remains integrated to the French technical and vocational education.[e]

- The word “design” has been officially in use among the two Ministries in charge of education in France[16] for less than twenty years. The first appearances of the term in an institutional context can be traced back to 1996, while its use for naming current curricula began in 2002.[17]

Before 2002, the institutional denomination that described what is now called “design” in France was “applied arts” (arts appliqués). Today, French high school students are still being taught design-related curricula under the “applied arts” denomination, in the dedicated baccalaureate training course called “sciences and technologies for design and applied arts” (sciences et technologies du design et des arts appliqués, abbreviated to STD2A). Postgraduate students engage in courses that earn them a postgraduate degree in applied arts (the Diplôme Supérieur d’Arts Appliqués [DSAA], which is comparable to a Master of Fine Arts [MFA]).

The prevalent historiography that contextualizes the study and the socio-cultural perception of design in French design schools still relies on its classical canon to provide its foundation. A strong focus is placed on the “pioneers’ era,” which covers the span of time from the beginning of the industrial revolution in the late 18th century to the onset of early modernism in the late 19th century through to contemporary times. Foundation references regarding the teaching of design history in France include Danielle Quarante’s Éléments de design industriel, Raymond Guidot’s l’Histoire du Design de 1940 à nos jours, Brigitte Flamand’s Le Design: Essais sur des Théories et des Pratiques, and Alexandra Midal’s Design, Introduction à l’Histoire d’une Discipline and Design, l’Anthologie.[18] While Flamand’s book progressively introduces aspects of design history that stretch beyond an understanding of design socially and economically defined inside applied arts’ and industrial design’s paradigms, all of the works mentioned above are still steeped in the usual subjects of study that constitute the canon of European design history: the Arts & Crafts movement, the Deutscher Werkbund, the Bauhaus, the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, the CIAM, the HfG Ulm, the New Bauhaus.

Currently, influential French design education figures f are advocating strongly to adopt the term “Design et Métiers d’art” (approximately translated as “Design and Crafts”) to replace the term “applied arts” in and around French design curricula. This advocacy might be interpreted as their latest move not only to separate design processes from artistic practices (and from the aesthetic and artistic focus the use of such terminology might convey), but also to embrace a discipline that is and has remained under a strong Anglo-American influence since the end of WWII. Adopting this terminology is perceived as a means to foster an understanding of design beyond its traditional aesthetically rooted, artifact creation-based considerations in France, without undermining the perception of design as a creative, conceptive and innovation-driven practice.[19][g]

Part 2: Evolving from Utilizing Method as a Tool for Desing-as-a-Practice, to Utilizing Method as a Condition for Design-as-Discourse

Référentiels de Formations: Setting Practices, Tools And Discourses

The référentiels de formation, or “référentiels” as they are commonly known in French educational circles, are instruments that have, under the guidance of the French Ministry of National Education, been widely adopted in France. They exist to establish and document a theoretical framework for effectively synthesizing, modeling and adapting the skills, bases of knowledge and ethical values necessary for an individual to successfully chart and operate a career path in a given professional activity. In accordance with meeting this goal, they are also used to establish the baseline skills, bases of knowledge and ethical values that guide vocational education curricula throughout the country. According to the Guide de Conception et de Réalisation d’un Référentiel (published by the International Commission on Education of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie), these types of documents should, after a thorough study of the professional context within which its guidelines and success metrics are to be applied, present a coherent and professionally significant and relevant set of skills that must be mastered during vocational training. Additionally, these types of documents should also depict and influence the theoretical and practical teachings necessary to prepare a student to enter a given professional discipline (while neither mandating the contents of the courses that comprise its curriculum nor the teaching strategies and tactics that should be adopted to ensure their effective delivery). Finally, these types of documents also fix the national testing standards that must be followed during the evaluation of students. While following the référentiels is not mandatory, their prerogative to describe and set a national standard for evaluation tends, of course, to generalize and standardize their use by teachers across France.

Connecting the professional world to the educational community (and back), a référentiel de formation almost always clearly indicates its purpose in its introduction. This is often expressed in these words: “the référentiel (plus the specific title of the document) aims to train students for the profession of (name of the professional activity).”[h] As a normalization instrument, Cros & Raisky fundamentally depict the référentiel as:

a social construct that clarifies the norms of an activity, or a meaning given to the social systems. [The référentiel] is what is regarded to inform how judgment or meaning is given to an object or action. In other words, the référentiel is a normative mediation tool that human activities can refer to (to relate to) when studying disparities or differences [...]. It does not claim to match reality or truth. It produces knowledge by the comparisons that may be done. [...] The référentiel serves as a marker for a social group that may subsequently take decisions and make choices with respect to this commonly accepted measure.[20][21]

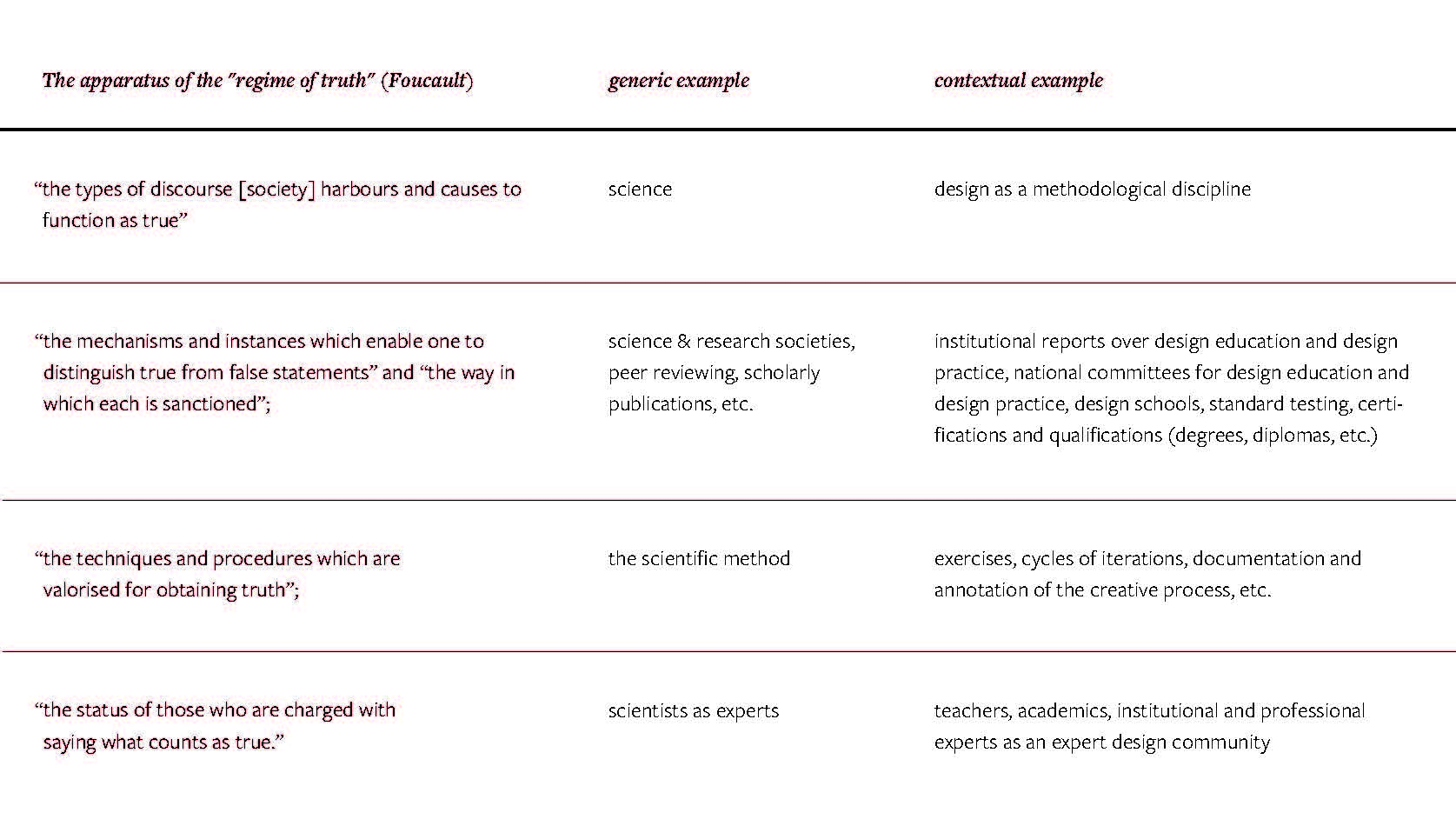

As far as vocational education is concerned, Cros & Raisky[22] remind us that vocationally focused higher education in France has been programmed to meet the professional objectives specified by the French Consultative Professional Committees during a series of initiatives that were triggered during a nationwide series of vocational education reforms leading to the publishing of a governmentally appointed set of references and standards documenting and describing the professional activities within the technical fields, and known as référentiels des métiers in 1972. This is particularly true regarding the operation of the French Brevet de Technicien Supérieur (BTS) undergraduate program for design, which is still the most popular curriculum among students pursuing design education. The “BTS” technical undergraduate degree usually requires two years of study after the completion of a French high school level of education, and is recognized as a diploma of higher education in France. As Figure 2 suggests, the référentiels de formation were conceived to ensure that whatever vocationally framed skill sets were described as being necessary by the référentiels des métiers to allow an individual to effectively enter a given profession could be adapted and translated into specific groupings of educational goals and standards.

We propose that allowing a particular set of instruments such as the référentiels de formation to act as a normative marker for locating or measuring the level of achievement of a given social group—like aspiring design students—makes it, in fact, a cultural marker. The utilization of instruments like these bolsters the idea among this type of a group that its members must refer and conform to a certain set of characteristics, instructions, and representations to attain and sustain belonging. Thus, the référentiels goal of reconstructing a representation of a professional field, or “a discipline’s biography”[23] has taken root in and around much of the design education in France. They nurture and guide what we call a narrative of design comprised of a logical disciplinary enumeration, organized in a certain order, concealed in documents, that is supposed to “[help us recall] significant events, coups, and changes in the discipline’s life.”[24]

The Référentiels as Performative Agents

Investigating the diverse array of institutional grey literature that now informs how vocational aspects of design are described and thus perceived in French educational and professional circles, it appears that “method” and “process” are the most common terms used to describe the diverse array of knowledge and understanding that informs the designer’s activity. In this case, “common” must be understood in every meaning of the word: both as an ordinary practice and as a shared practice In other words, method and process refer to the standard, skill-based know-how that designers might have in common, as proposed in the référentiel du DSAA spécialité Design:[25] “the designer is primarily a synthetic professional, capable of undertaking a research process based on the exploitation of analytical systems, and the implementation of ethical, aesthetic and meaningful values.”[26] The skills required to design the methods, or processes, that guide design decision-making are clearly identified:

- “to develop a general and artistic knowledge;

- to master French language, written and spoken;

- to master narrative processes;

- to master several artistic / visual languages;

- to master information technologies;

- to master processes of conception and conceptualization: researching information, running surveys and field observations, analyzing, synthetizing, problematizing;

- to integrate design strategies, including marketing strategies and planned management of a creative process;

- to manipulate and experiment advanced design and production tools through specific workshops adapted to the relevant professional sector;

- to master creative strategies and visual thinking;

- to master written and visual means of expression;

- to organize and manage team work.”[27][28]

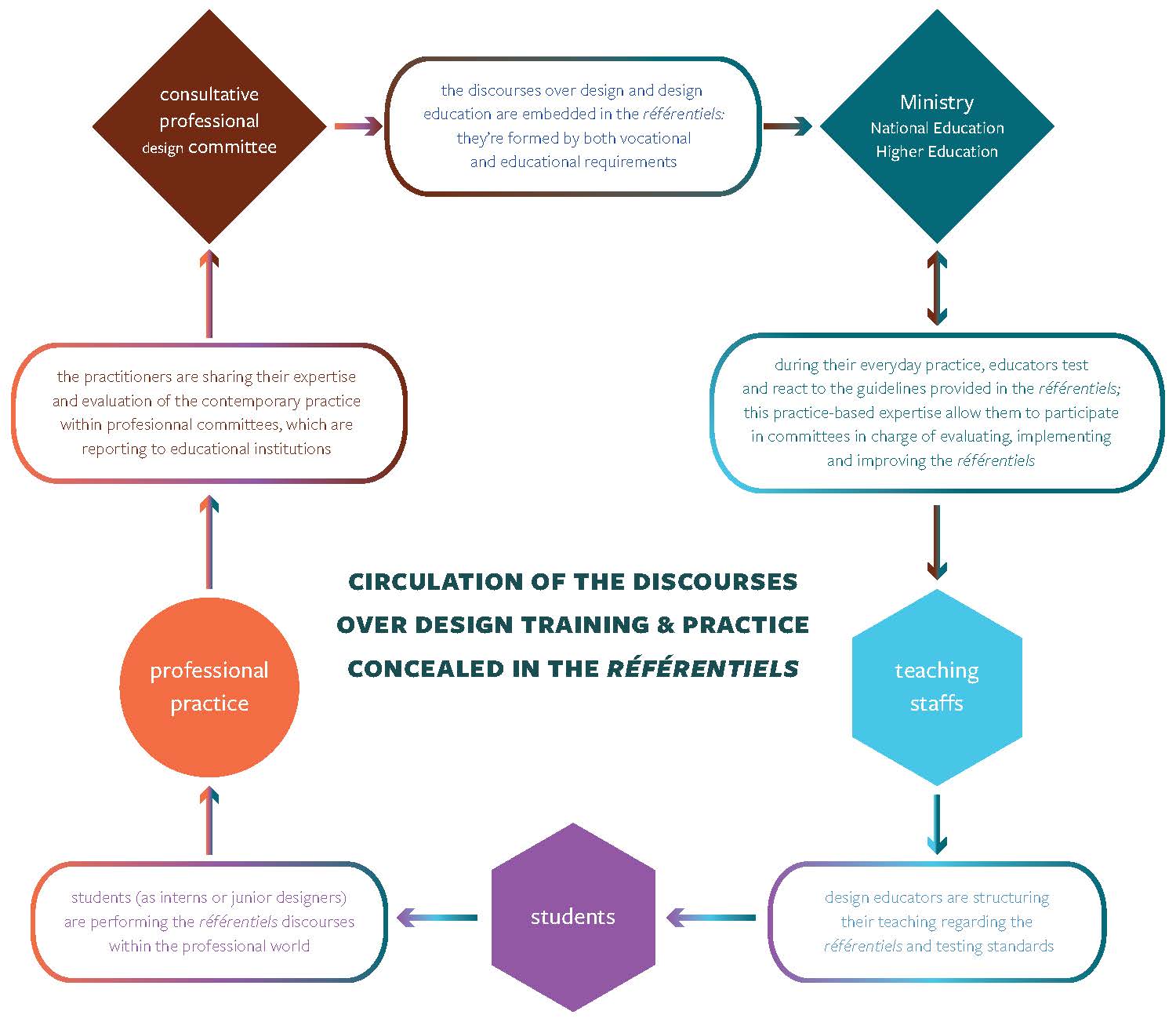

These skills are then divided into practical and cultural items “sub-skills” to be acquired that design students must master, while each course necessary to train these students to attain them are described.

The institutional literature identifies the need to understand, formulate and operate methods and processes as part of the core know-how that a professional designer must possess, who is supposed to “enter her process of design & creation through a programmatic methodology[29] which is being reinvented for each context of intervention”.[30][31] Still, the référentiel not only proposes quite a frail definition of this adaptative “programmatic methodology”—“to elaborate research methods (analyzing, defining issues)”[32]—but also implies that methods are left to young designers to invent. Following the référentiel, the way to learn methods is to elaborate methods.

The paradox goes on, as “the essential thing is not so much about following an established and fixed scientific method, rather drawing the relevant lines, defining an original method, even if it changes along the way”.[33][34] Rather than serving as an objective set of logical operations to run a project, “method” might need to be thought of as a process constantly reinventing and adjusting itself. If we acknowledge that the process of design is inherently an iterative one, we oppose that this kind of “method” should not be mingled for an objective methodological model but more as a methodical bricolage based on one’s ability to work intuitively and iteratively—as the ancient Greek-language root suggests it (meta-odos, i.e. “that leads the way”). This paradox indicates a possible shift from thinking about method in and around design as an objective and logical tool, to that of method as a semantic marker to reiterate the specificity of design as a discipline and a practice.

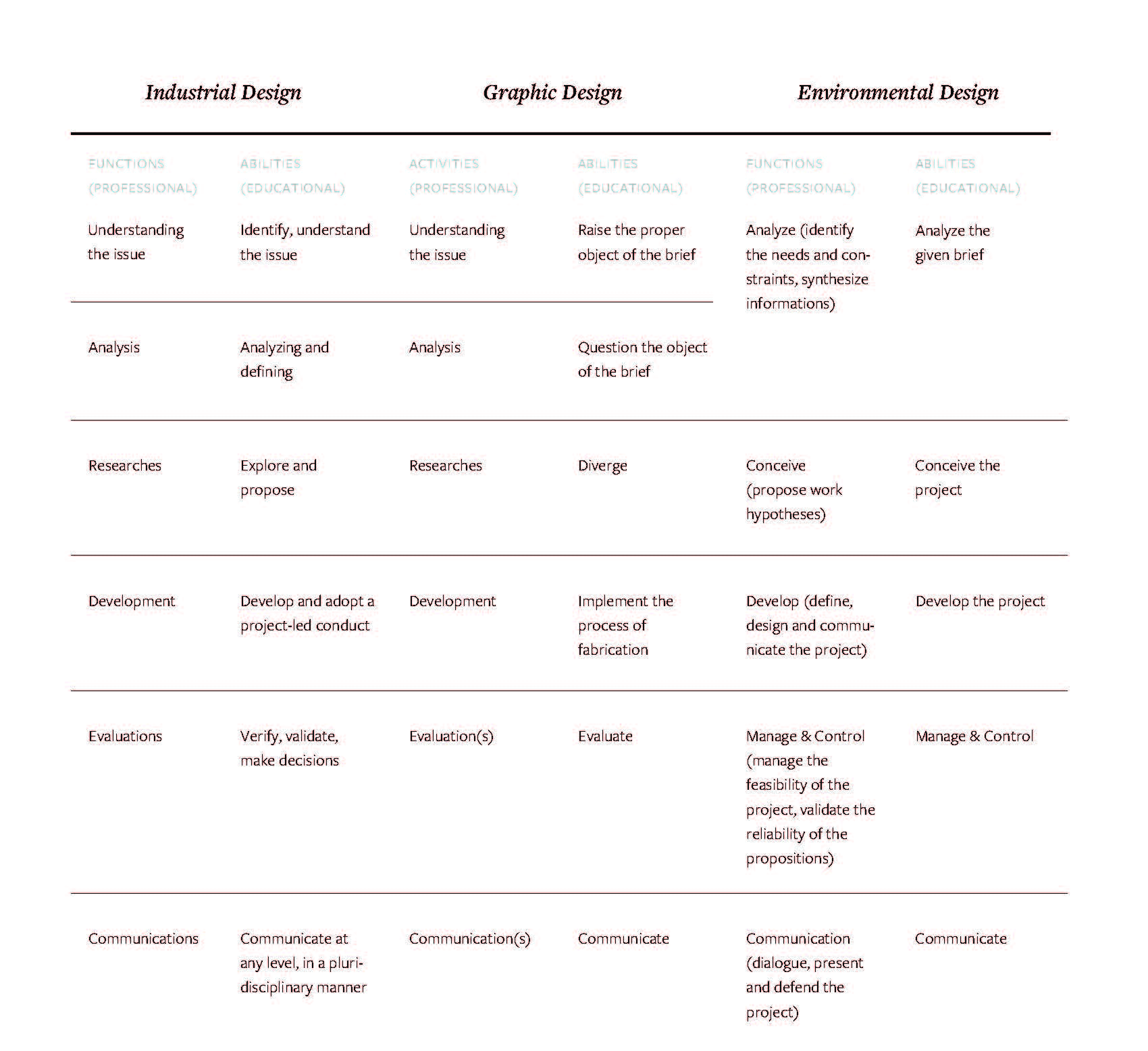

As the French reform of the higher design education curriculum that started in the mid-90s was finally completed in 2014, each référentiel prepared the ground for the next one. This occurred in every design program, from industrial design to graphic design, and affected undergraduate through postgraduate curricula. This search for a harmony across the sub-disciplines of design was imbued with a will to fix common educational goals and methods, and to share common terminology and set equivalent testing contexts. This helped us outline a fundamental methodological approach that seems to guide the formulation and operation of the design project as it is currently taught at the undergraduate level across many French design curricula.

In short, we identified the following methodological pattern:

- item 1: understand a given brief;

- item 2: analyze the brief and its context, the issue(s) raised by the brief;

- item 3: search and experiment with multiple and diverging hypotheses;

- item 4: establish a primary hypothesis and develop a project;

- transversal item 1: evaluate the results;

- transversal item 2: communicate.

Working within this pattern, the référentiels still sustain their reader in a blurry theoretical space where “methods” and “methodology” are consistently used as symbolic references, including within the context of the document itself (see figure 3), although these terms are inconsistently described and defined. Thus, if we stick to the operations that are actually described here, such as “research,” “analyze” and “define,” we must agree that they differ from one another, and might not be naturally or logically connected. As we will discuss it, this vague terminology keeps circulating among the majority of the French educational community, which contributes to misunderstandings and uncertainty about what is supposed to constitute a proper method for engaging in the process of design.

In order to observe the possible effect of these narratives of design practice (i.e. their possible performativity) on the structure of various design education curricula in France, we will analyze the results of the interviews and surveys we conducted among two groups of undergraduate design students enrolled at the École de Condé-Paris to further our understanding of the students’ point of view in the next section of this report.

Part 3: Investigating the Students’ Discourses Over Design Practice and Methods

First Round of Observation (January 2015): Method Vs. Mischief

In the following sections, we present the results of the observations mentioned at the beginning of Part 1 of this paper (Elements for an investigation of the French model for design education). These observations were conducted during two workshops meant to introduce postgraduate design students to project-grounded and practice-led research. As these workshops were intended to investigate how the context of a given design project (professional practice or practice-based research) could possibly rearrange or otherwise affect design methods, it seemed appropriate to attempt to identify how the students perceived, described and tested these methods. What follows is our analysis of the results of a series of semi-structured group interviews with the students during the first workshop, as well as the surveys we distributed anonymously to the students during the second workshop. These observations were meant to document the students’ experiences with and thoughts about engaging in various types of design methods.

The first array of interviews we conducted followed the interrogations initiated during the workshop and presented above: we were seeking more insight into the students’ views of their personal practice of design, as well as how they perceived the process of engaging in particular design methodologies, and in their overall perception of their experiences of being enrolled in a design education program. The interviews were conducted at the end of the workshop, immediately after their last team presentation. We (Frédéric Valentin and Justė Pečiulytė) presented ourselves to the students as researchers, differentiating ourselves from their teachers and guest instructors, and encouraged them to speak freely. We began our interactions with them by looking for distinctions between their personal approaches to designing. In light of this, we asked them to:

- describe their methods (what kind of tools they were using, the different stages of their design process, etc.);

- to describe what characteristics they thought a good design teacher should have or embody;

- what personal ways of working they would use and would not divulge to their teachers (e.g. they knew it was not a formal procedure) and finally;

- we asked them to tell us who was the “misbehaver” (the literal term used to describe an attitude towards design promoted in the workshop) in their team, and to explain why.[i]

To analyze the students’ responses, we chose to use qualitative analysis mainly following the “long interview” method described by McCracken[35] to understand the students’ collective understanding of their design education and design practice.

We made several observations regarding the students’ responses, as articulated below:

- They seemed to agree that there were some institutionalized methods shared among them (especially within a specific design discipline) that they acquired through practice (in the sense that they did not study it). Most of the time, they referred to these methods through the common objects that had been specified as desired outcomes by their teachers;

- While the common method for engaging in a given design process was expressed in rather formal ways—“we made a series of initial sketches”—their descriptions of the intent of the actual activity underlying these descriptions was fairly vague. On the one hand, the desired end of the design process, e.g. the results that would supposedly meet the teachers’ demands, was described quite clearly and qualified as “rational,” as being grounded in reality. On the other hand, personal interpretation of the method for engaging in the process, and of the different objects that could have successfully satisfied the demand, while erratic, were highly grounded in reality (“how it was truly realized or accomplished”), while its end product was described in more vague terms, both with regard to the quality of the project (often described as “utopian”), and the benefits of the exercise (personal growth, reflection, etc.).

Based on our interpretations of these observations, we propose the following interpretation: as the students seemed to be able to identify a common understanding of a “method,” the actual execution of this method also seemed to be open to interpretation. If the different stages of this method are presented as “logical,” or “normal,” it seemed to be principally serving a communicative, narrative purpose. Following this method through to the realization of specific objects led to a coherent narrative that could be validated by the teachers and understood by the other students.

This narrative becomes the ideal of a design practice, where design products are the result of a rational process, from the analysis of a context and user to the proposition of a solution. However, the students revealed that, in practice, they rarely follow the proposed scheme, usually starting with an initial, more intuitive idea, and then “retro-engineer” their own project in order to justify this initial idea to their teachers. This type of activity yields a type of engagement by students in what we have deemed a “narrative black box” (Figure 4), which occurs when a student or students engage in the following sequential steps:

- the demand for a given design outcome is nurtured with various inputs, including the brief provided by the teacher, as well as a set of relevant references identified as design productions;

- students evolve and elaborate the development of their project based on their inclination to follow an intuitive response;

- finally, they retroactively extract a project narrative from their own work that is seemingly relevant enough to satisfy what they understand as institutional, disciplinary and educational expectations and parameters.

Second Round of Observation (November 2015): Describing Methods

This second round of observation took place during an introductory workshop on design research methodology divided into five courses (one course a week from November 16th to December 14th 2015) delivered by four different contributors (including their regular teacher / thesis supervisor, in charge of the annual Design-Research seminar). During this workshop, the design teacher proposed that her students figure out how practice-oriented tools could possibly be shifted to research-oriented tools to guide design decision-making.

We were careful not to disclose the actual locus of our study, especially to the teachers we were working with, as we were looking for clues that would reveal how they perceived both design practice and the cultural constructions that frame the mediation, transmission and practice of design, in both the teachers’ and students’ speech and attitudes. Despite this, the supervising teacher informed her colleagues who chose to participate in and contribute data to our study of her actual educational purpose: that of discovering or inventing ways to raise her students’ awareness as to the research value of their design skills, and encouraging them to shift these skills from a design practice approach to a design research approach.

This second set of data collected about our students’ understanding of their practice was gathered through an anonymous survey[j] distributed in two parts[k] to the students during this workshop (and therefore, with a different set of students). As we engaged in this activity, we were still uncertain of the type of data we needed to collect, and of the exact nature of our research question, which meant that we couldn’t ensure a rigorous structure to or the relevance of every aspect of the survey. After several reexaminations and reconsiderations of our research method and of the data we collected, we dismissed parts of the results.[l]

Even accounting for this, the qualitative part of the survey has provided more reliable data, as it directly called for descriptive accounts of their practices and views, with complete freedom in the choices of words to express them. Students were asked an open question about their engagement with a particular design method. They were first asked to (1) describe the different steps of this design method and its practice. They were then asked (2) if this method was subject to variation, (3) if they were taught this method, (4) if knowledge of it was widely shared among their classmates and, last, (5) if they thought it was relevant in terms of being able to operationalize it in professional design practice.

Many students described engaging in a similar method using the same official terminology described earlier in this paper: analysis J research and experiment J development. However, while using this very same generic terminology, the way they described engaging in their step-by-step method often revealed a rather distinctive understanding of these common terms. For example, depending on the case, “development” could be understood as the exploration of various hypotheses through visual experiments or as pursuing one specific hypothesis to completion and finalization of the project. In the same way, “research” could be understood as artistic explorations or as searching relevant inputs to nurture the project (art and design references, bibliography, materials, techniques, etc.). Any practice related to the transversal items derived from the référentiels (such as “evaluation of the results” and “communicate”) was quite rarely depicted, as if design practice was strictly limited to “analysis, research and development.”

While it seems quite obvious that any student would develop—as they are so often asked to—a personal approach and their own tools, what is described here is beyond these considerations: it is not a diversity of appropriations led by personal interests (even though some of students specified, when needed, the personal or unusual nature of the method described),[m] but a diversity of interpretations led by an apparent lack of common definitions.

Such lack of a shared understanding of the basic terminology of the design process echoes the référentiels: in fact, despite the use of a unified terminology naming the major functions of the design process (see our previous chapter “the référentiels as performative agents,”) we can observe that, from one référentiel to another, this terminology might describe different step of the process, different skills and capacities, etc. (Figure 5)

This circulating institutional lingo actually helps fuel the inclusion of the educational community in the wider design community: if this lingo fails to objectively describe and validate the formalization of an actual design method (not to mention a methodology), it nevertheless participates in strengthening a cultural representation of design as a method-based, solution-oriented discipline and the self-identification of aspiring designers.

Conclusion: Design Methods as a Black Box, Design Education as a Weltanschaaung

In France, reaching a consensus on what design is and what it means to design is difficult, as it is not an inherent part of our vocabulary, and as it defies basic, mainstream understanding among cross sections of French society: the use of the word “design” is widely heterogeneous not only among mainstream French audiences, but also among design students and educators—not to mention the way(s) it is understood as a practice. Indeed, if design is often used by mainstream media and marketing as a trendy adjective to describe furniture or built environments or apparel in a contemporary or modern style, it is also seen as a way to convey a more creative approach to conception and, as a result, can also be used to describe specific courses in engineering and management —such as the post-graduate program “Innovation by Design” offered by ENSCI-Les Ateliers.[n]

In fact, the progressive shift from applied arts toward design education in France is in itself politically and ideologically motivated, promoting a specific understanding of the role of design in our society, of its motivations, whether a consensus about these role and motivations is reached, or not.

In the pursuit of this investigation, as in our common experience within the extended design community, we observed that while the agents of design are often unwilling to partake in the debate of the definition of design, they generally associate the term with a great diversity of conception and ideological discourses. Steve Harfield argues that, “design is fundamentally driven by its inherent preconceptions and determinate choices about how the world shall be seen and thus how the future world should be enacted.”[36] Aside from the consequences on design’s disciplinarity, this argument is supported by the importance that ideologies and political views took in design history: Alain Findeli[37] explains that each school was influenced by specific political standpoints articulating “art, science and technology” and developed their curricula accordingly.

Meanwhile, design methodology seems to coincide with an attempt to articulate design practice to a set of academic methods and systems. It seems meaningful to point out here that the establishment of the Design Research Society (1966) was built upon ideas that emerged during the first Conference on Design Methods held in London in 1962.[38] Still, the shift from a practice-based reflection over methods, to an academic attempt to modelize design methodology through a science-based systematic framework soon raised controversies:

“However, the 1970s also became notable for the rejection of design methodology by the early pioneers. Christopher Alexander said: ‘I've disassociated myself from the field ... There is so little in what is called ‘design methods’ that has anything useful to say about how to design buildings that I never even read the literature anymore ... I would say forget it, forget the whole thing ... If you call it ‘It’s A Good Idea To Do,’ I like it very much; if you call it ‘A Method,’ I like it but I’m beginning to get turned off; if you call it ‘A Methodology,’ I just don’t want to talk about it.’ ” (Alexander, 1971)[39]

Not a field of design activities seemed spared, even when admittedly framed by academic requirements, as suggested by Nicolas Nova:

“[...] Because of a so-called confidentiality of methods along with secretive attitude of design agencies—or a methodological void?—this situation gives the impression that design ethnography is a black box that is easy to mention since it does not need people to justify what it means [...].”[40]

We may endorse Nova’s comment to describe our own experiences in the classroom, which led us to consider the fact that the educational ensemble formed by design educators, design students and the professional world might be using the same language without necessarily designating the same activity. To put it roughly: what are we, design actors—whether we are practitioners, students, teachers, researchers—really manipulating and sharing altogether when discussing design methods and methodology? Are we really discussing disciplinary tools and processes in order to question them, implement them, develop them, and improve them? Or are we trying to establish a common culture based upon a common set of semantic markers, even if their meaning remains imprecise and imprecisely shared, in order to perform and legitimate the existence of our discipline?

Our survey suggests that praising if not advocating not only the existence of “methods,” but also the reduction of design practices to a set of vague adaptative and solution-oriented methodological tools might hide the agency of what we have described as a narrative black box (Figure 5). The narratives of “methods” may in fact be a powerful educational tool, establishing the foundations of a common education and culture, and while pushing students to position themselves towards it (whether in a confident or defiant way), leading them to autonomy, critique and reflexivity in their practice.

References

- Austin, J. L. How to do things with words (second edition). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1975.

- Borisenkova, A. “Narrative Foundations of Knowing: Towards a New Perspec-tive in the Sociology of Knowledge.” Sociological Research Online, 14.5 (2009): 17. Online. Available at http://bit.ly/2ydzXLQ; (Accessed 01 June 2017).

- Branzi, A. & Gentili, L. La casa calda. Milano, Italy: Idea Books, 1984.

- Cros, F. & Raisky, C. “Autour Des Mots de La Formation: Référentiel.” Recherche et Formation, 64.1 (2010): pgs. 105–116.

- Cross, N. “Designerly ways of knowing.” Design Studies, 3.4 (1982): pgs. 221–227.

- ———— . “A History of Design Methodology.” In Design Methodology and Relationships with Science, edited by M. J. de Vries, N. Cross and D.P. Grant, pgs. 15–27. Dordrecht, Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1993.

- Springer. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-015-8220-9_2.

- ———— . Engineering Design Methods: Strategies for Product Design. 4th Edition. Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

- Design Research Society. “History of DRS.” Design Research Society (website). 2016. Available at: http://www.designresearchsociety.org/cpages/history/ (Accessed 01 June 2017).

- Findeli, A. “Rethinking Design Education for the 21st Century: Theoretical, Methodological, and Ethical Discussion.” Design Issues 17.1 (2001): pgs. 5-17.

- ———— . “La recherche-projet en design et la question de la question de recherche : essai de clarification conceptuelle.” Sciences du Design 1.1 (2015): pgs. 45–57.

- Flamand, B., ed. Le design: Essais sur des théories et des pratiques. Paris, France: Editions du Regard, 2006.

- Gordon, C., ed. “Michel Foucault. Power! / !Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977”, translated by C. Gordon , M. Marshal, J. Mepham and K. Sober. New York, ny, usa: Pantheon Books, 1980.

- Guidot, R. 2004. Histoire du design de 1940 à nos jours. Revised edition. Paris, France: Hazan, 1994.

- Harfield, S. “On the Roots of Undiscipline.” In Undisciplined!, Proceedings of the Design Research Society Conference, 16-19 July 2008, Sheffield Hallam University, UK, edited by D. Durling, C. Rust; L-L. Chen; P. Ashton; K. Friedman (eds.),. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Hallam University,2008: pgs. 151-161.

- Hatchuel, A. “Quelle Analytique de La Conception ? Parure et Pointe En Design.” In Le Design. Essais Sur Des Théories et Des Pratiques, edited by B. Flamand, pgs. 147-161, Paris, France: Editions Du Regard, 2006.

- Kazi-Tani, T., Valentin, F., Pečiulytė, J., Brulé, E. & Mivielle, C. “Good people behave. Bad people design. Misbehaving as a framework for design and design education.” Poster presented at the IASDR Conference 2015, Brisbane, Australia, November 2-5.

- Koskinen, I. Zimmerman, J., Binder, T., Redström, J., & Wensveen, S. Design research through practice: From the lab, field, and showroom. Waltham, MA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann, an imprint of Elsevier, 2011.

- Laurent, S. Les arts appliqués en France. Genèse d’un enseignement. Paris, France: Éditions du CTHS, 1999.

- Latour, B. Pandora's hope: essays on the reality of science studies. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Loewy, R. La Laideur se vend mal. Paris, France: Gallimard, 1990.

- Mackay, W. E. & Fayard, A.L. “HCI, Natural Science and Design: A Framework for Triangulation across Disciplines.” In Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques, 18-20 August, 1997, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, edited by Coles, S. New-York, NY, USA: ACM Press, 1997: pgs. 223-234. Online. Available at: https://www.lri.fr/~mackay/pdffiles/DIS97.Triangulate.pdf (Accessed 01 June, 2017).

- Margolin, V. World History of Design. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2015.

- McCracken, G. The Long Interview. 1st edition. Newbury Park, CA, USA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 1988.

- Mendini, A., Caramia, P. & Geel, C. Ecrits d’Alessandro Mendini: Architecture, Design et Projet. Dijon, France: Les Presses du réel, 2014.

- Midal, A. Design l’Anthologie. Genève, Switzerland: HEAD; Saint-Étienne, France: Cité du Design, 2013.

- Midal, A. & Laurent, F. Design: introduction à l’histoire d’une discipline. Paris, France: Pocket, 2009.

- Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale. “Arrêté de création d'une classe de mise à niveau d'arts appliqués”. Bulletin Officiel, 34 (Sept. 27, 1984). Online. Available at: http://designetartsappliques.fr/sites/default/files/ManAA%20-%20Arrete%2017-07-1984.pdf (Accessed 01 June 2017).

- Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale. Direction de l’Enseignement Supérieur. Référentiel de Formation et de Certification—Brevet de Technicien Supérieur Communication Visuelle option Graphisme Édition Publicité. Paris, France: Centre National de Documentation Pédagogique, 2001.

- Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche. Direction de l’Enseignement Supérieur. Référentiel de Formation et de Certification—Brevet de Technicien Supérieur Design de Produits. Paris, France: Direction de l’Enseignement Supérieur, 2005.

- Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale. “ENS de Cachan : objectifs de formation, programmes,horaires et durée hebdomadaire des interrogations orales depremière et seconde années des classes préparatoires – section C, arts et design.” Bulletin Officiel, 28 (July 11, 2013). Online. Available at: http://www.education.gouv.fr/pid285/bulletin_officiel.html?cid_bo=72702 (Accessed 01 June 2017).

- Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche. Design et Métiers d’Art, report prepared by B. Flamand, serial 2015-077. Paris, France: Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, 2015.

- Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche. Direction de l’Enseignement Supérieur. Brevet de Technicien Supérieur Design de Communication Espace & Volume. Paris, France: Direction de l’Enseignement Supérieur, 2008.

- Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale-Direction de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche. Direction Générale de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de l’Insertion Professionelle. Référentiel des activités professionnelles et de certification du Diplôme Supérieur d’Arts Appliqués Design. Paris, France: Direction Générale de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de l’Insertion Professionnelle, 2012.

- ———— . Référentiel de Formation et de Certification — Brevet de Technicien Supérieur Design Graphique Option A : Médias Imprimés & Option B : Médias Numériques. Paris, France: Direction Générale de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de l’Insertion Professionnelle, 2012.

- Moholy-Nagy, L. Vision in Motion. Chicago, IL, USA: Paul Theobald & Co, 1947.

- Morris, W. Hopes and Fears for the Arts. London, UK: Ellis & White, 1882.

- ———— . 1887. “How We Live and How We Might Live.” Commonwealth, vol.3, no.73, June 1887.

- Munari, B. Design as Art. Translated by Patrick Creagh. London, UK: Penguin Books, 2008.

- Nova, N. Beyond Design Ethnography: How Designers Practice Ethnographic Research. Berlin, Germany: SHS; Genève, Switzerland: HEAD, 2014.

- Bulletin Officiel Hors Série no. 2. “Positionnement et aménagement de la formation au Brevet de Technicien Supérieur” (27 March, 1997).

- Quarante, D. Eléments de design industriel. 3rd edition. Paris, France: Economica, 2001.

- Rams, D. “Omit the unimportant.” Design Issues, 1.1 (1984): pgs. 24-26.

- Ruskin, J. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Revised edition. New York, NY, USA: Dover Publications, 1989.

- Sottsass Jr., E. “Me dichono que sono cattivo (They say that I’m wicked),” Casabella, no. 376 (April 1973): p. 15.

- Sullivan, L. “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered.” Lippincott’s Magazine, no. 57 (March 1896): pgs. 403-409.

- Vial, S. “De la spécificité du projet en design : une démonstration”, Communication & Organisation, 46.2 (2014): pgs. 17-32.

Biographies

Tiphaine Kazi-Tani is a design researcher (Cité du Design, Saint-Étienne, France & Codesign Lab, Telecom ParisTech) and educator (École de Condé-Paris & ENSAAMA). He explores design as a part of an hegemonic apparatus (“dispositif”), but also as the possibilities of design-as-resistance. After focusing on "misbehaved" practices of architecture and urbanism, and specifically in examining the conditions that surround the production of the contemporary public space and possibilities of life within urbanized environments, he is now pursuing research to identify minoritarian design practices. This follows the work of Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari (1975), as he believes that such practices might propose operating design alternatives and resistance to / within contemporary, dominant apparatuses. He was part of the curatorial team of the Biennale Internationale Design 2017. (tiphaine.kazi-tani@citedudesign.com)

Frédéric Valentin is a Ph.D. candidate from Codesign Lab at Telecom-Paristech, under the direction of Annie Gentès. He previously studied product design at École Boulle de Paris and at École Normale Supérieure de Cachan. His research focuses on open-design, and the status of the artifacts it creates, in contrast to common industrial design artifacts. His hypotheses are that open-design suggests a specific aesthetic and thus requires a different attitude toward design process. (frederic.valentin@telecom-paristech.fr)

Notes

- a

Grey literature refers to materials and research produced by organizations outside of the traditional commercial or academic publishing and distribution channels, such as report literature, government publications, policy documents, etc. These materials often vary in quality, and often are not peer-reviewed, but are protected by intellectual property rights, and are often collected by libraries and other types of institutional repositories.

- b

The referring teacher invited a design research PhD. candidate, a designer / practice-based PhD. candidate, an artist / practice-based doctor in fine arts and a doctor in science & technologies studies. candidate to present their work and help the students to ascertain the differences between professional design practice and design research.

- c

Graphic design, fashion design, industrial design and environmental design.

- d

Considering the local specificity of this literature, we have chosen to keep the French word référentiel to designate these documents throughout our essay. Likewise, we have decided to stick to their original tone to render this sometimes unclear and confusing institutional lingo. In order to do so, we have translated them as literally as possible, as long as the meaning would remain correct: that’s why some formulations might sound archaic or peculiar. We also decided to provide our readers with the original texts, which have been placed in notes.

- e

The technological curricula, which led to much of the focus on vocational studies at the undergraduate level, begins in high school and includes diverse academic sectors such as: sciences & technologies for sustainable development, design and applied arts, professional techniques of the dance and music sector, management sciences & technologies, sciences & technologies for social care and healthcare, laboratory technologies and techniques, sciences and technologies for agriculture, and techniques and technologies for the hospitality industry.

- f

Such as Alain Cadix, former director of renowned design school ENSCI-Les Ateliers (see note 33), editor of the report “Pour une politique nationale de design” commissioned by the “Ministère du redressement productif” (Ministry for productive recovery) and “Ministère de la culture et de la communication” (Ministry for culture and communication) and currently member of INMA (“Institut National des Métiers d’Art”) scientific and cultural board.

- g

“Creativity” and “innovation” are prevailing terms associated with the perceptions of the purpose of design in France, particularly as a driving force for industrial development and economic recovery. In her book “Le design: Essais sur des théories et des pratiques”, Brigitte Flamand attributes a large portion of French industries’ difficulties with regard to competing in the globalized marketplace to a casual reluctance towards engaging in more creative and risky practices embodied by creative industries and design’s overall interests. In part, she bases her hypothesis on the success of countries adopting such politics, notably through design education.

- h

E.g., the definition of the role and activity of a graphic designer according to the 2000 “référentiel” for the BTS Communication Visuelle—undergraduate vocational degree in graphic design: “The holder of the degree [...] designs, implements and coordinates the implementation of a visual communication process, from the initial brief for which the needs and constraints are specified [...] the holder of the degree can: be hired as an employee or as a consultant assisting the artistic director of an advertising agency, an independent design studio or an integrated studio [...]; practice as an independent graphic designer.” [our translation: “Le titulaire du BTS Communication Visuelle [...] conçoit, met en œuvre et coordonne la réalisation d’un processus de communication visuelle, à partir d’une commande initiale pour laquelle lui sont précisés les besoins et les contraintes [...] Le titulaire du BTS Communication Visuelle peut s’insérer comme salarié ou comme consultant en qualité d’adjoint à la direction artistique d’une agence de publicité, d’un studio de création ou d’un studio intégré [...] ; exercer en tant que travailleur indépendant en tant que graphiste.”

- i

These questions, while directive, were only meant to suggest the themes of the discsion. We then tried to follow the students’ discourse, asking them for clarification and details, when necessary.

- j

For the purpose of our research, we could not disclose the subject of our research to our contributors completely. However, we made sure that we were as clear as possible about how we intended to use the data we collected, and we took every precaution we could to ensure the anonymity of their responses.

- k

The survey was distributed in two parts, because some of the speakers’ interventions could have influenced the students’ responses.

- l

We dismissed quantitative data or questions with multiple choices of answers, constraining the respondent in a preset vocabulary, giving too much orientation and leaving very little for us to read about the student’s thoughts in the end (also considering the rather limited size of our set).

- m

In this survey, as in the interviews, the students regularly opposed this method to enable their subjectivity, either to praise its objectivity (the fact that it contributed to a rigorously established result, conformed to “reality”), or to deplore its pedagogic, unimaginative qualities (they felt it inhibited their necessary creativity). Some students specified the rather impersonal and cliché nature of this description before they expressed a more personal approach.

- n

École Nationale Supérieure de Création Industrielle, opened in 1982, under the patronage of Jean Prouvé and Charlotte Perriand, is still widely considered as the best design school in France and one of the best in Europe. Matali Crasset, Mathieu Lehanneur or Patrick Jouin are ENSCI alumni.

Austin, J. L. How to do things with words (second edition). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Findeli, A. “Rethinking Design Education for the 21st Century: Theoretical, Methodological, and Ethical Discussion.” Design Issues 17.1 (2001): pgs. 5–17.; Findeli, A. “La recherche-projet en design et la question de la question de recherche: essai de clarification conceptuelle.” Sciences du Design 1.1 (2015): pgs. 45–57.; Hatchuel, A. “Quelle Analytique de La Conception? Parure et Pointe En Design.” In Le Design. Essais Sur Des Théories et Des Pratiques, edited by B. Flamand, pgs. 147-161, Paris, France: Editions Du Regard, 2006.; Cross, N. “Designerly ways of knowing.” Design Studies, 3.4 (1982): pgs. 221–227.; Cross, N. “A History of Design Methodology.” In Design Methodology and Relationships with Science, edited by M. J. de Vries, N. Cross and D.P. Grant, pgs. 15–27. Dordrecht, Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1993. Springer. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-015-8220-9_2.; Cross, N. Engineering Design Methods: Strategies for Product Design. 4th Edition. Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.; Koskinen, I. Zimmerman, J., Binder, T., Redström, J., & Wensveen, S. Design research through practice: From the lab, field, and showroom. Waltham, MA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann, an imprint of Elsevier, 2011; Vial, S. “De la spécificité du projet en design : une démonstration”, Communication & Organisation, 46.2 (2014): pgs. 17-32.

Morris, W. Hopes and Fears for the Arts. London, UK: Ellis & White, 1882.; Moholy-Nagy, L. Vision in Motion. Chicago, IL, USA: Paul Theobald & Co, 1947.; Ruskin, J. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Revised edition. New York, NY, USA: Dover Publications, 1989.

Mendini, A., Caramia, P. & Geel, C. Ecrits d’Alessandro Mendini: Architecture, Design et Projet. Dijon, France: Les Presses du réel, 2014.; Munari, B. Design as Art. Translated by Patrick Creagh. London, UK: Penguin Books, 2008.; Branzi, A. & Gentili, L. La casa calda. Milano, Italy: Idea Books, 1984.; Sottsass Jr., E. “Me dichono que sono cattivo (They say that I’m wicked),” Casabella, no. 376 (April 1973): p. 15.; Rams, D. “Omit the unimportant.” Design Issues, 1.1 (1984): pgs. 24-26.

Latour, B. Pandora's hope: essays on the reality of science studies. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Gordon, C., ed. “Michel Foucault. Power / Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977,” translated by C. Gordon , M. Marshal, J. Mepham and K. Sober. New York, NY, USA: Pantheon Books, 1980.

Findeli, A. “La recherche-projet en design et la question de la question de recherche: essai de clarification conceptuelle.” Sciences du Design 1.1 (2015): pgs. 45–57.

Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche. Design et Métiers d’Art, report prepared by B. Flamand, serial 2015-077. Paris, France: Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, 2015.

“Ainsi de l’atelier à l’industrie, l’ambition était de former des maîtres artisans qualifiés, hors de l’atelier et des corporations. C’est dans cette même logique que la ville de Paris crée, à la fin du 19ème siècle, les premières écoles professionnelles municipales, tout comme à Lyon, pour bien former de jeunes ouvriers de l’art qualifiés. L’arrivée d’André Malraux participera à la séparation structurelle et intellectuelle entre art et technique engageant durablement la rupture entre arts et formations professionnelles des arts appliqués à l’industrie et aux métiers d’art.”

See Laurent, S. Les arts appliqués en France. Genèse d’un enseignement. Paris, France: Éditions du CTHS, 1999.

Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale and Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche.

Quarante, D. Eléments de design industriel. 3rd edition. Paris, France: Economica, 2001.; Guidot, R. 2004. Histoire du design de 1940 à nos jours. Revised edition. Paris, France: Hazan, 1994.; Flamand, B., ed. Le design: Essais sur des théories et des pratiques. Paris, France: Editions du Regard, 2006.; Midal, A. & Laurent, F. Design: introduction à l’histoire d’une discipline. Paris, France: Pocket, 2009.; Midal, A. Design l’Anthologie. Genève, Switzerland: HEAD; Saint-Étienne, France: Cité du Design, 2013.

Cros, F. & Raisky, C. “Autour Des Mots de La Formation: Référentiel.” Recherche et Formation, 64.1 (2010): p. 107.

“Le référentiel est un construit social qui clarifie les normes d’une activité ou d’un sens donné à des systèmes sociaux. Il est ce par rapport à quoi un jugement ou un sens est donné à un objet ou une action. Autrement dit, le référentiel est un outil de médiation normatif permettant aux activités humaines de s’y référer (de s’y rapporter) pour étudier un écart ou des différences [...]. Il n’a nullement la prétention de correspondre à du réel ou une réalité. Il produit des savoirs par les comparaisons que l’on peut faire. [...] Le référentiel sert de repère pour un groupe social susceptible par la suite de prendre des décisions et de faire des choix par rapport à cette mesure acceptée communément.”

Borisenkova, A. “Narrative Foundations of Knowing: Towards a New Perspective in the Sociology of Knowledge.” Sociological Research Online, 14.5 (2009): 17.

Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale-Direction de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche. Direction Générale de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de l’Insertion Professionnelle. Référentiel des activités professionnelles et de certification du Diplôme Supérieur d’Arts Appliqués Design. Paris, France: Direction Générale de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de l’Insertion Professionnelle, 2012. p. 7.

“Le designer est avant tout le professionnel de synthèse capable d’entreprendre une démarche de recherche fondée sur l’exploitation de systèmes d’analyse et la mise en œuvre de valeurs éthiques, signifiantes et esthétiques.”

“Développement d’une culture générale et artistique; maîtrise de la langue française écrite et orale ; maîtrise de la communication en langue anglaise; maîtrise de la narration; maîtrise des langages plastiques; connaissance des techniques de réalisation; maîtrise des technologies de l’information et de la communication; maîtrise des processus de conceptualisation et de conception: recherche d’informations, enquête, analyse, synthèse, problématisation; intégration des stratégies de conception: stratégies marketing et gestion planifiée d’un processus de création en design; manipulation d’outils de conception et de production avancés par le biais d’ateliers dédiés au secteur d’activités professionnelles; maîtrise des stratégies de création affirmation d’une pensée visualisée; maîtrise des moyens d’expression rédactionnels et visuels; organisation et gestion du travail d’équipe.”

“Le designer entre dans son processus de conception-création par une méthodologie programmatique qui se réinvente à chaque contexte d’intervention.”

Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale-Direction de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche. Direction Générale de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de l’Insertion Professionnelle. Référentiel des activités professionnelles et de certification du Diplôme Supérieur d’Arts Appliqués Design. p. 25.

“L’important n’est pas tant de suivre une méthode scientifique avérée et figée, que de définir des axes pertinents, une méthode originale, quitte à en changer en cours de route.”

McCracken, G. The Long Interview. 1st edition. Newbury Park, CA, USA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 1988.

Harfield, S. “On the Roots of Undiscipline.” In Undisciplined!, Proceedings of the Design Research Society Conference, 16-19 July 2008, Sheffield Hallam University, UK, edited by D. Durling, C. Rust; L-L. Chen; P. Ashton; K. Friedman (eds.),. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Hallam University, 2008: pgs. 151-161.

Findeli, “Rethinking Design Education for the 21st Century: Theoretical, Methodological, and Ethical Discussion.”

Design Research Society. “History of DRS.” Design Research Society (website). 2016. Available at: http://www.designresearchsociety.org/cpages/history/ (Accessed 01 June 2017).

Nova, N. Beyond Design Ethnography: How Designers Practice EthnographicResearch. Berlin, Germany: SHS; Genève, Switzerland: HEAD, 2014: p. 37.