Virtual Essay: This is How You Become Number One: Some Very Helpful Thoughts and Drawings by Alex Egner

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Introduction

Like every red-blooded American with a WiFi connection, I feel entitled (and possibly even obligated) to share my opinions, stream-of-consciousness style, with the world. But, unlike some of my fellow Americans,[a] I try to be judicious. My career—first as an art director with a global ad agency and now as a graphic design educator—has made me keenly aware of target audiences. If I feel inclined to post a vitriolic screed on Facebook, I must first consider how it will affect those it reaches.

My social media network cuts across a diverse swath of people: high school classmates from my hometown in suburban north Texas; aunts, uncles, and cousins in rural Kansas; friends from graduate school; colleagues in academia; the parents of my son’s soccer[b] teammates. The list goes on. To paraphrase a classic Seinfeld television episode, Facebook is the place where all my worlds collide[1]

Individually, I can talk to almost anyone from among this diverse array of people and find some kind of common ground, even if only by sticking to uncontroversial topics like the weather or the likeability of Tom Hanks. When speaking face to face with another human being, I intuitively tailor my message to that particular person. But when using social media, I’m unable to do this, as the platform operates as an indiscriminate bullhorn: the same message, absent of nuance, gets blasted to everyone. This makes it tricky when you feel inclined to publish an opinion that will upset approximately 46.1 % of the American population.

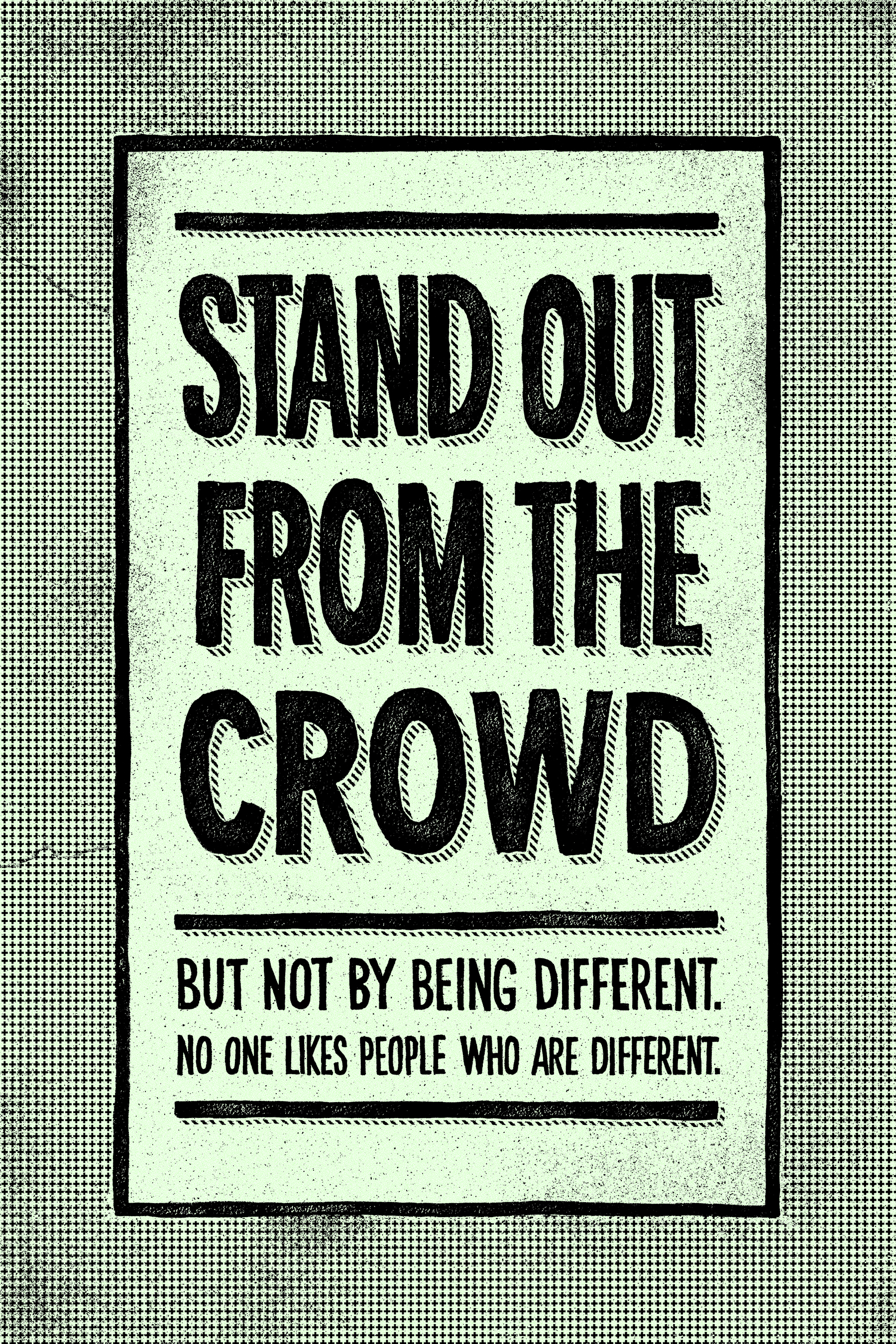

I usually opt to take a more indirect approach when I need to express my feelings about a particular social, cultural, or political state of affairs. Call me cowardly, but I avoid the fruitless arguments of internet comment boards. Therefore I craft no screeds, just a few cruddy[c] drawings. As a lifelong doodler, I frequently rely on drawing to organize my thoughts. Doing this helps me give visible form to invisible feelings. And, beginning on November 8, 2016, I certainly had some feelings.

I had a deep sense of anxiety and sadness about the new type of world, and the new type of America, that might unfold as a result of the national elections that had taken place in the U.S. on that day. As a result of my unease, I felt compelled to begin work on the collection of drawings that are partially reproduced on the following pages under the title “This Is How You Become Number One.”

Instead of depicting specific American politicians, their party affiliations, or their policies, I focused on examining core human values that one would hope most people living in democratic societies share. I drew pictures and wrote accompanying aphoristic slogans that were deceptively simple. The childish drawings, aside from accurately reflecting my competency[d] as a draftsperson, are intended to disarm people—as was the purposefully naïve pastel color palette I selected. In sum, image, text, and color were ironically combined to appeal to an audience that might otherwise be averse to such messages.

The title of this collection is meant to express the idea shared by so many Americans, that no matter how terrible things get politically, economically or socially in the U.S.—even if our nation devolves into a post-apocalyptic hellscape—we are still the best in the world[e] The collection is loosely premised around the concept of a self-help book, created specifically for people who want to succeed at the expense of others. The series incorporates themes of unchecked ambition, entitlement, misanthropy, and greed. It also includes depictions of some anthropomorphized animals.

The journalist Malcom Gladwell, speaking in an episode of his Revisionist History podcast called The Satire Paradox, [2] criticizes some forms of parody for being too ambiguous in their intent. He argues that, depending on the political bent of the audience, the piece of satire will be interpreted to match the viewer’s existing beliefs. Speaking about Stephen Colbert’s blowhard pundit character from the Comedy Central Network’s television show The Colbert Report, Gladwell explains “The more liberal you are, the more you see Colbert as a liberal skewering conservatives. But the more conservative you are, the more you see Stephen Colbert as a conservative skewering liberals.”

However, rather than being a mark of ineffective satire, I find this type of ambiguity to be appealingly sneaky. America’s political polarization[f] causes many Americans to block out all opinions that are different from our own. We often have visceral, knee-jerk reactions to points of view that differ even slightly from those we hold most dear. With this in mind, perhaps it’s nice to create content that all, or at least most, sides of the political spectrum are willing to engage with. Or, in this case, to create content that all sides of the political spectrum are willing to ignore. The completed series was originally published serially (two per week) on Instagram to an audience of only 166 followers[g] This is the first time that a curated set of these images has been published en masse.

References

- Gladwell, M. “The Satire Paradox.” Episode 10, podcast date 08.18.16. Revisionist History. Online. Available at: http://revisionisthistory.com/episodes/10-the-satire-paradox (Accessed 10 June 2017).

- Mandel, D. “The Pool Guy.” Episode no. 118, season 7, episode 8, broadcast date 16 November 1995. Seinfeld Scripts. Transcribed by Coogan, D. 27 January 2007. Online. Available at: http://www.seinfeldscripts.com/ThePoolGuy.html (Accessed 22 May 2017).

Biography

Alex Egner is a graphic designer, art director, and Assistant Professor of Graphic Design at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington, USA. His work has been featured in Communication Arts, PRINT, LogoLounge, Graphis and HOW, and has earned awards from the Dallas Society of Visual Communications, The Type Directors Club, AIGA 365, and The Addys. He holds an MFA in Communication Design from Virginia Commonwealth University and a BFA in Communication from the University of North Texas. More of Alex’s work can be viewed at http://www.alexegner.com/.

Notes

- a

- b

I.e., association football. With all due apologies to Dialectic's international audience.

- c

The editors of scholarly journals like Dialectic tend to frown on the use of vague descriptors like “cruddy,” so they have asked that I provide a definition here. Cruddy, in this usage, refers to a drawing’s general shoddiness, inferior quality, and low-brow aesthetics—as though it was drawn by a manchild with tiny, fumbling hands.

- d

- e

- f

A phrase that has been written / spoken no less than 400 trillion times over the past year.

- g

I hereby openly and shamelessly solicit your viewership: Please follow @eggnerd on Instagram.

Mandel, D. “The Pool Guy.” Episode no. 118, season 7, episode 8, broadcast date 16 November 1995. Seinfeld Scripts. Transcribed by Coogan, D. 27 January 2007. Available at: http://www.seinfeldscripts.com/ThePoolGuy.html (Accessed 22 May 2017).

Gladwell, M. “The Satire Paradox.” Episode 10, podcast date 08.18.16. Revisionist History. Available at: http://revisionisthistory.com/episodes/10-the-satire-paradox (Accessed 10 June 2017).