Book Review: Mapping the Grid of Swiss Graphic Design: A review of 100 Years of Swiss Graphic Design

Compiled and edited by Christian Brändle, Karin Gimmi, Barbara Junod, Christina Reble, Bettina Richter (hardcover, 2013); published by Lars Müller Publishers, Zurich, Switzerland; 384 pages, approximately 600 illustrations. ISBN: 9783037783528.

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

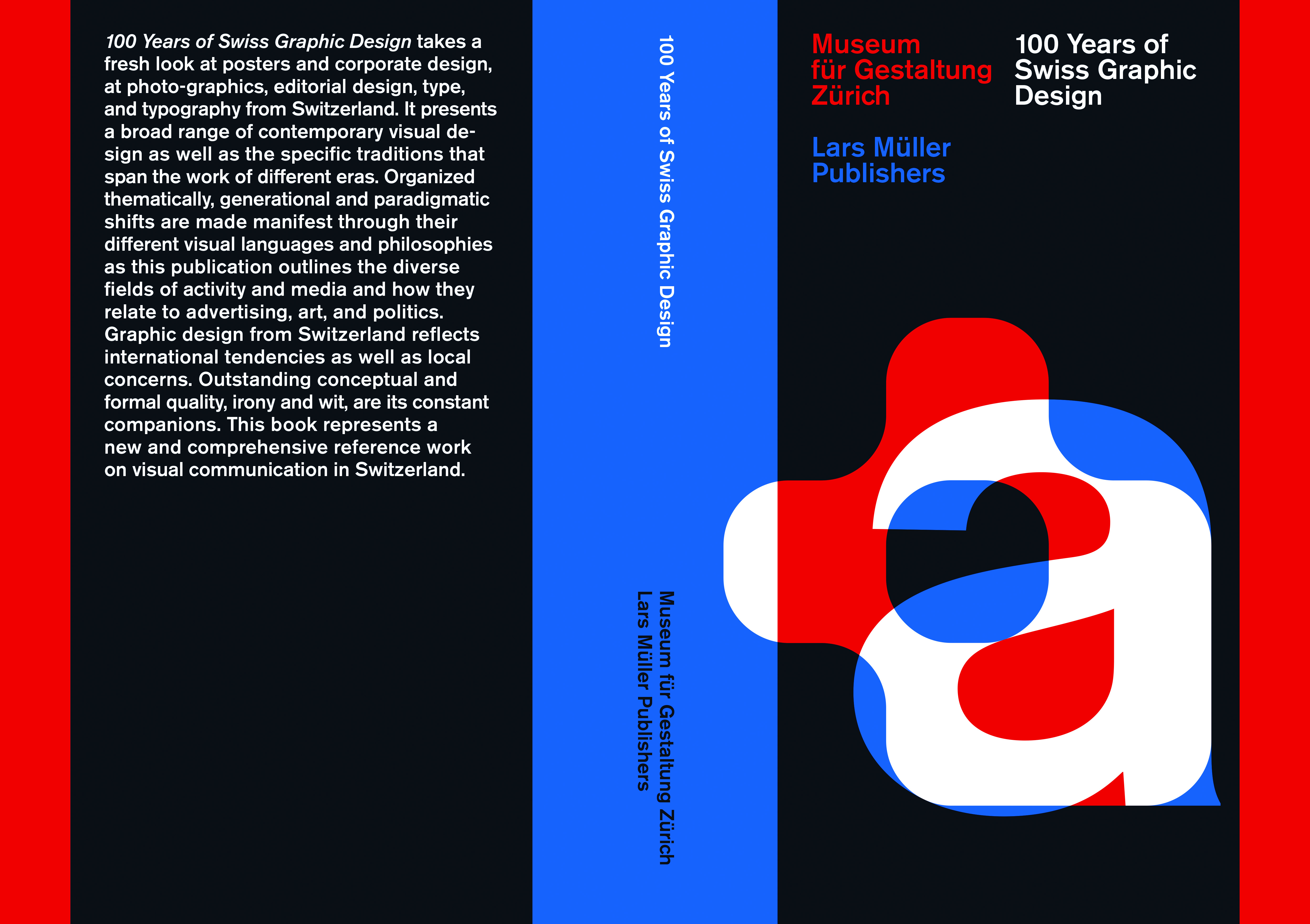

Book cover, Mapping the Grid of Swiss Graphic Design: A review of 100 Years of Swiss Graphic Design, edited by Brändle, Gimmi, Junod, Reble, and Richter.

Book cover, Mapping the Grid of Swiss Graphic Design: A review of 100 Years of Swiss Graphic Design, edited by Brändle, Gimmi, Junod, Reble, and Richter.100 Years of Swiss Graphic Design is a new, comprehensive reference work that presents a fresh perspective on Swiss graphic design and typography. It offers a behind-the-scenes look at the renowned graphic design collection of the Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, Switzerland’s leading design and visual communication museum. However, as editor Christian Brändle explains in the foreword, the book offers more than a “mere inventory” of the museum’s collection. Drawing from sources beyond the museum’s collection, the book traces the origins of Swiss graphic design and typography, while also offering a wide range of examples of contemporary Swiss visual communication design. It provides a rich array of familiar Swiss classics as well as a broad range of material that is much less well known, including sketches, posters, packaging, stamps, maps, banknotes, design system manuals, and type specimens. According to editor Karin Gimmi, “The choice of the images was done together with the designers of the book. The studio NORM, with Manuel Krebs, Dimitri Bruni and Ludovic Varone, had a big share in defining the visual content of the book. We tried to find a good balance between eye-catching objects and such that are less known.”

The publication is divided into eleven chapters that are sequenced thematically into important developments in the canon of Swiss graphic design and that feature several types of visual communication design artifacts. Many chapters begin with a short essay that serves to frame and place its topic in the historical conditions that existed within Switzerland and throughout Europe during specific spans of time. These are followed by explanatory case studies. Each case study adds new layers of depth by exploring the social, technological and political trends that helped bring new forms of visual communication design into existence. As Gimmi explains, “The thematic approach was indeed chosen to replace a biographical one. While some of the entries profit from earlier research work, others are based on completely new material.” The wealth of material spanning several generations is supplemented by comprehensive analysis by academics, historians, and a network of expert curators within the Museum für Gestaltung Zürich’s poster and graphics collection. The aim of the editorial team, as Gimmi described, was to “try and set a new standard” for graphic design surveys.

The poster as a popular advertising medium in Swiss visual communication design is presented first, but continues to feature prominently throughout the rest of the book. The first chapter examines posters produced by Swiss designers, or designers working in the Swiss style, over the course of the twentieth through the early twenty-first centuries, beginning with the first Sachplakat (“Poster style”) poster by Emil Cardinaux in 1908. The essays outline the medium’s artistic evolution, universal visual language, distinctive approaches, and steady advancement in new directions. Most notable from the early period of the twentieth century are a number of posters advertising products and publicizing Swiss tourism. These include work from such prominent poster designers such as Emile Cardinaux, Niklaus Stoecklin, Herbert Leupin, Hans Erni, Otto Baumberger, as well as Swiss-born belle-époque Parisian artists Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen and Eugéne-Samuel Grasset. Despite these designers having diverse artistic backgrounds and careers, many shared a painterly style, and, from a conceptual standpoint, sought to create compositions of typography and imagery that concisely and effectively conveyed essential meaning about the goods and services they had been designed to promote. Another important consideration for this group was using the medium of the poster to reach wider audiences as communication and transportation technology rapidly evolved across Europe.

The Swiss school, also referred to as the “International Style,” materialized as a design movement during the 1950s and 1960s, sought what its practitioners believed to be a more universal and scientific approach to solving design problems. An entire chapter in this volume, “Swiss Style,” is dedicated to examining this movement with a series of illuminating case studies: the first tracks its evolution, followed by pieces that analyze the perspective of the “Swiss Style” from abroad, the affect that the implementation of the J. R. Geigy AG corporate image had on corporate identity design in the United States, the influence the Ambassadors of Swiss design had in Italy, and culminating with a short history of the development and evolution of the typeface Helvetica. Richard Hollis’ essay: “The New Graphic Design: Views from Abroad,” details the individuals and publications that were influential in spreading the new “Swiss Style” to an international audience. Hollis’ piece also provides a unique first-person perspective on how and why the aesthetic trends of the movement have remained stable, and that examine how the formal characteristics of Swiss graphic design distinguish it from other movements and styles that have affected graphic design over the last hundred years.

A broad range of modern Swiss graphic design—work designed from the late twentieth century and the 2000s—is represented throughout the book. The final case study, “Autonomy and Assignment,” provides interviews with five contemporary Swiss graphic designers: Ruedi Wyss, Natalie Bringolf, Kristin Irion, Tania Prill, and Manuela Pfrunder. These Swiss designers were asked to discuss their working history, design ideas, working methodology, and the importance of the reception of Swiss graphic design as communicated by exhibition institutions, the press, and publications. Although the designers interviewed indicated that their particular working methods varied—from approaches guided by methodically operated research and tightly defined frameworks to those informed by investigative analyses of “stuff lying around a table”—they were united in that almost all of them were design educators, and that they all believed in the importance of maintaining strong, dynamic relationships in their studios between design teams and those who guide their working processes.

The primary criticism of this book, as is so often the case with specifically located graphic design histories, concerns the weight of emphasis placed on individual (in this case, Swiss) graphic designers. Given that the process of selecting whose work should be included in a volume like this is made difficult due to the sheer volume of designers who have produced outstanding work from which to choose, it is unfortunately not surprising that the work of several important designers was not given sufficient emphasis. The contributions of Ernst Keller, considered an instrumental Swiss design educator and a key figure in the development of the Swiss design movement, is mentioned only sparingly in the text. Additionally, Siegfried Odermatt and Rosmarie Tissi, partners of the design firm Odermatt & Tissi, are given limited attention in the text, and are only granted page space for three images between them. As Odermatt and Tissi played a leading role in applying the International Typographic Style to corporate and cultural visual communications, they deserved more attention than they received in the book.

100 Years of Swiss Graphic Design was designed by Dimitri Bruni, Manuel Krebs, Teo Schifferli, and Ludovic Varone of NORM, an experimental team of graphic designers based in Zurich. Graphic design monographs are genuinely challenging for a designer to effectively develop and execute, due to the sheer volume of historical material and breadth of content they must accommodate, yet the design team at NORM has risen to the call as evidenced by their design of this book. Gimmi offered, “We had very close cooperation with NORM, with whom we [have worked] together on different occasions. There have been a lot of discussions both about content and form of the book.” The book cover is made formally seductive by virtue of its elongated shape, minimalist color palette (black, white, red and blue), and sparsely rendered graphic and typographic forms. This composition is comprised of two graphically intersecting letterforms rendered large enough to occupy most of the available surface area. A slightly blurred and pixelated lower-case ‘a’ from the typeface FF Moonbase Alpha (designed by the Swiss-born designer Cornel Windlin in 1991) is juxtaposed with the lower-case ‘a’ from the a revival version of the typeface Antique (designed by the Swiss typeface designer François Rappo in 2010-11). The carefully assembled cover image of overlapped shapes fittingly captures the elemental graphic-form language that evolved from a new generation of Swiss graphic designers in the 1950s. The well-balanced weight of images and text on the interior pages facilitates a simple and elegant reading experience throughout this volume. The pages are dense with information, but possess a high degree of graphic exactness clearly arranged according to an underlying grid-structure.

Overall, 100 Years of Swiss Graphic Design is an engaging and comprehensive historical survey, accompanied by numerous examples of the vast body of design work to have emerged from Switzerland in the past century. Showcasing visual design across a wide range of niche areas of expertise, this invaluable book demonstrates how many Swiss designers’ use of modernist elements along with their considerate graphic deployment of constructivist ideals continue to exist as an indelible part of today’s graphic design language. It is essential reading for design students, or anyone interested in Swiss graphic design and its larger effects on the discipline worldwide. It is a salient contribution to the development of graphic design history as a scholarly discipline, and a comprehensive account of a period of significant artistic creativity.